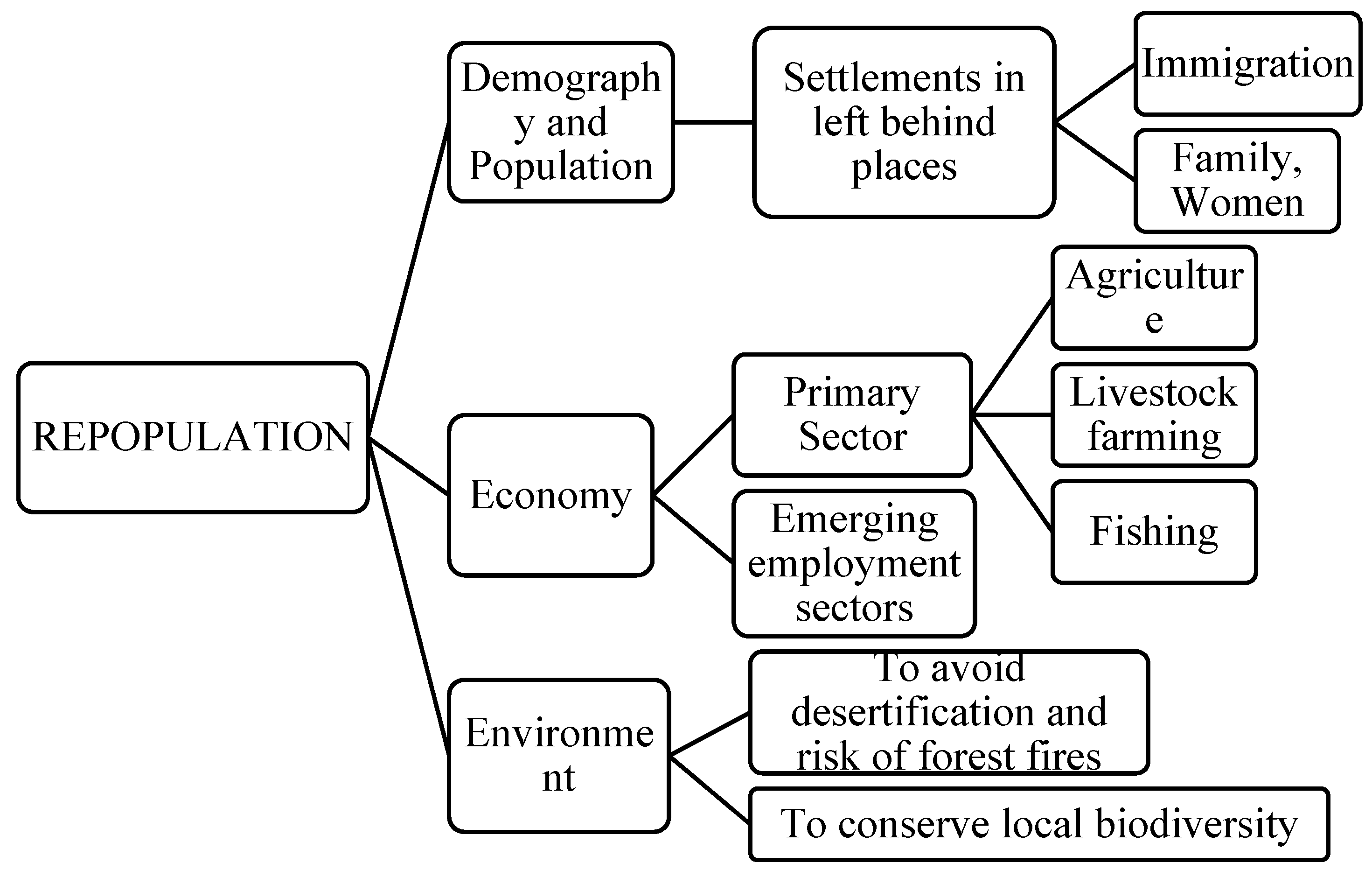

The results of this analysis is divided in 3 areas: Problems or rural depopulation; On population settlements; Defining repopulation and; Current models or rural repopulation.

3.1. Problems of Rural Depopulation

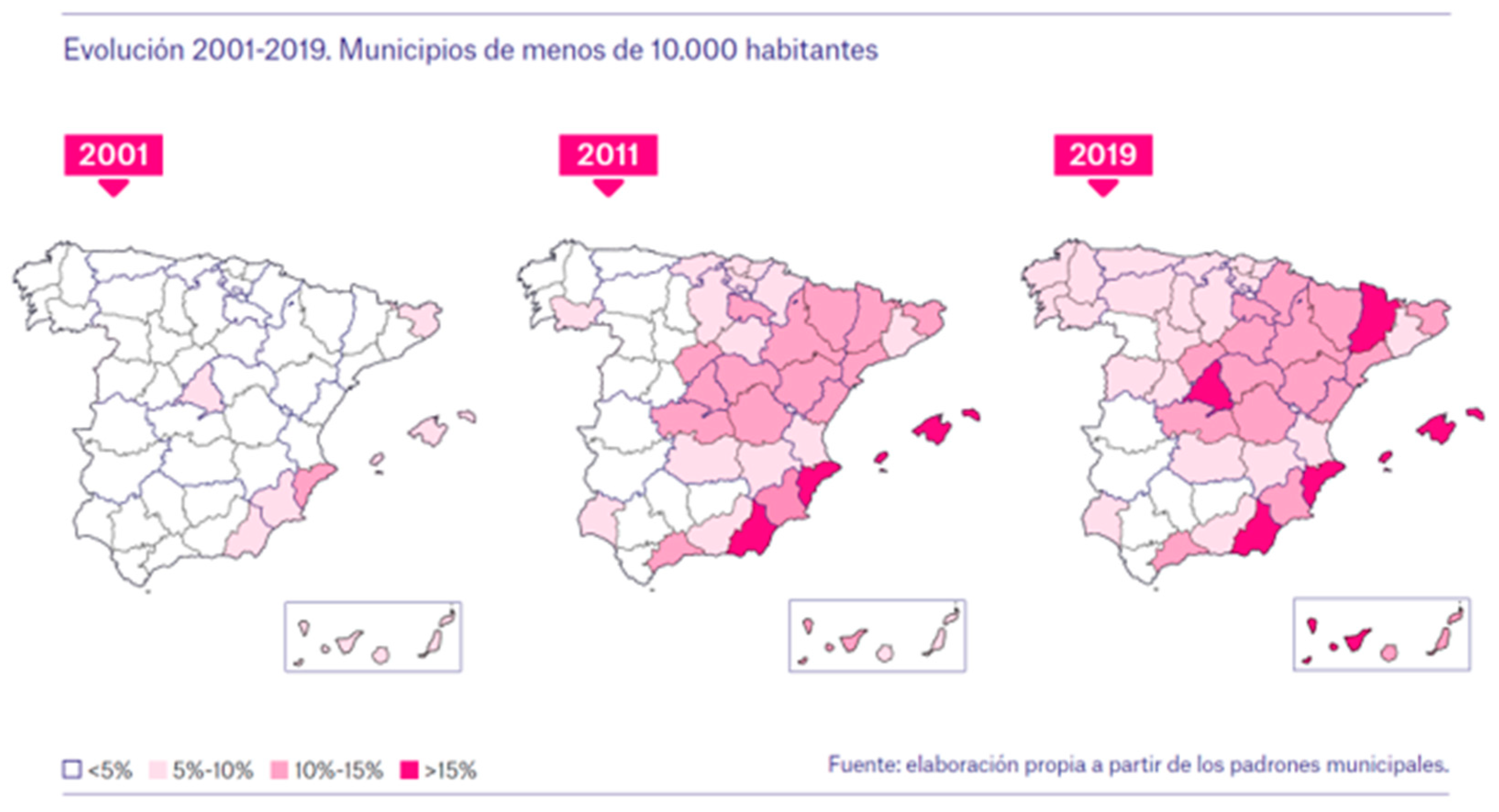

Unlike in large cities, depopulation is most clearly evident in rural areas where some 42% of municipalities have seen their populations decline. According to the INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España) some 45,000 people abandon rural communities annually. The process of rural depopulation brings with it a series of negative consequences, summarised below:

The public resources available in each municipality are reduced due to smaller and aging population:

Access to healthcare is a problem as there are fewer and more dispersed health centres, clinics and hospitals, requiring people to travel longer distances for care. This problem is even more acute given that an aging population has more healthcare needs and often with reduced mobility or autonomy.

Schools and education present similar problems. With fewer children, individual schools need to serve a number of different communities requiring transportation to take students to larger local towns. For secondary and higher education options are even more limited and the majority of students must move to larger towns or cities far from home.

Other public services and administration, managing taxes, fees, etc. require local residents to travel to the provincial capitals, except where these services can be conducted online.

There are fewer and less frequent transportation options, and many towns remain without internet services (fibre optic networks).

There is less economic development with few young and qualified people. There is less diversity or choice in employment as local consumption shrinks with ever fewer businesses serving local communities.

The quality of governance suffers due to a lack of resources and distant connection to regional and national centres of power.

There is greater precarity and poor quality of life for rural women whose access to education, training and employment is limited, in addition to other inequalities which condition their circumstances and discourage remaining in rural areas (there are fewer women than men in rural communities in Spain) [

9]. Contrarily, studies have suggested that the quality of life of women is higher in rural communities, where they then to enjoy better health and have more positive attitudes [

10].

The abandonment of the land is endangering the preservation of biodiversity, increasing desertification and forest fires due to neglect of the environment. Agriculture, cattle farming and traditional rural trades and crafts are increasingly unattractive options for young people offering poor economic opportunities and a life of hard labour, along with the added uncertainties of a changing climate. The average age of rural farmers in Spain is 61.

The cultivation of certain native species is declining due to a lack of workers, leading to a reduction in food production.

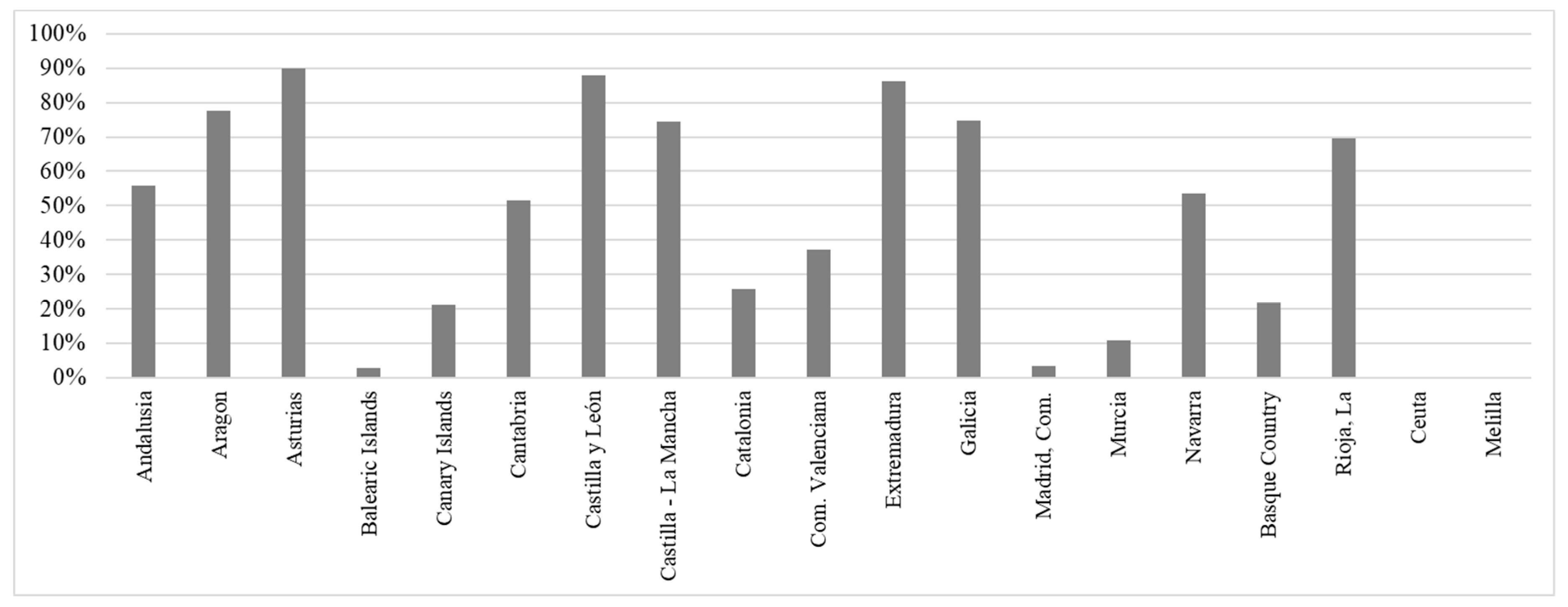

Immigration is one of the few factors which may serve to increase rural populations. As noted, Spain has a positive migratory balance, mitigating the natural decline; the same can be said for rural communities. In fact, immigrants now account for 10% of the rural population, an ongoing trend over the last 20 years, as illustrated in

Figure 3 below.

With this overview of the realities of rural depopulation in Spain, the problems it entails, and the key role played by immigration as the only population group experiencing growth, we shall now take a historical look at colonisation and repopulation efforts in Spain which may be instructive for the present.

3.2. On Population Settlements: A Brief Historical Review of Rural Colonisation and Settlement Models in Spain

Throughout history, the Iberian Peninsula has been subject to continuous demographic changes, colonisation, depopulation and repopulation. Settlements were conditioned by the complex and diverse geography of the region: the topography of the terrain, flat or mountainous, the abundance or scarcity of water relieve, surrounding vegetation or existing building techniques [

11].

Colonisation can be dated back to the earliest prehistoric periods: migrations, contacts and settlements beginning in the Neolithic era, as suggested by findings of Cardium pottery in the east of the Iberian Peninsula, dated between the 6

th and 5

th millennium BC [

12], and continuing to grow during the Metal Ages with the development of navigation. This explains the development of local cultures, such as Los Millares, during the Copper Age, 4

th and 3

rd millennium BC in the southeast of the Peninsula [

13]; the Argar, Bronze Age, 2

nd millennium BC in the southeast [

14], and Megalithic art found especially in the west and southwest of the Peninsula dating from the 5

th to 2

nd millennium BC.

During Ancient times, Greek and Roman sources, such as Herodotus, Polybius and Strabo, told of the inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula: Tartessians, 12th to 5th century BC, Iberians, 4th to 3rd century BC, and the arrival of Indo-European settlers and Mediterranean traders throughout the Levante.

During the 8

th century BC, waves of migration brought Indo-European settlers to the Peninsula, including the Celts, who established themselves in the north, centre and Atlantic regions [

15].

A significant role in colonisation was also played by the great trading civilisations of the Eastern Mediterranean from the 1st millennium BC, some drawn by primarily commercial interests, such as the Phoenicians (at their height in the 7th century BC), the Greeks (6th century BC) and the Carthaginians (3rd century BC) or, as with the Romans, by conquest, occupation, economic exploitation and Romanisation from the 3rd century BC.

Emigration and development led to an increase in the population density of the Peninsula, especially in areas where the growth in trade was greatest, urban centres as well as agricultural and livestock farming regions. The population rose from four million inhabitants in pre-Roman times, according to Pliny the Elder, to six million during the Roman era [

16,

17].

During the Middle Ages, there were significant migrations and processes of population and repopulation after the fall of the Roman Empire: the Visigoths, originating in the east of Germany, ruled over the Hispano-Roman majority in the ensuing power vacuum. They settled in largely abandoned or destroyed regions of Spain, creating an important agricultural and commercial centre in Baetica, establishing military garrisons on the frontiers to guard against incursions by other Germanic peoples [

18].

In the Middle Ages, during the long process of advance and conquest of Al-Andalus by the Christian kingdoms, different models of repopulation and allocation of lands were applied at different times and in different regions. Between the 8th and 10th centuries, reconquest brought with it a significant repopulation of the Duero valley, previously a “no man’s land”.

From the 8th century, as the Muslims advanced across the Iberian Peninsula, the nobles and clergy fled north, abandoning the territory and leaving it not only a devoid of inhabitants but of authority and hierarchies as well. Initially, this was a spontaneous process, called the Presura or Aprisio in Cataluña, and then continued more formally by order of the king. In the 10th century, on the initiative of the kings of Asturias, monarchical power was reasserted through local authorities (nobles and clergy) who were granted extensive lands that were brought under cultivation, diversifying crops and livestock, extending and increasing the economic power and dominion of the Christian kingdoms in the north.

Over the course of the 11th and 12th centuries, the northern kingdoms undertook the repopulation of the lands between the Duero and Tajo rivers, creating local councils and towns with specific laws and Alfoces: Comunidades de villa y tierra; generally with a central town fortified with perimeter walls or castle for defence.

This model of settlement was similar to that found in Italian region of Lazio, known as

incastellamento [

19] or ‘encastlement’, a form of purposeful social and economic organisation rather than a contingent development of military strongholds with regional jurisdiction.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, it would not be farmers or peasants but military orders which benefitted from lands conquered from the Muslims in the Tajo, Guadiana and Lower Ebro regions, materialised in Encomiendas, a form of manorialism through which the kings of Castilla granted agricultural land to these military orders, with the figure of the comendador, a knight of the order with authority and seignory over the region.

From the 13th century, in territories conquered from the Nasrids, the Guadalquivir Valley and Murcia, the models of resettlement were Repartimientos bringing settlers from Castilla to occupy the land abandoned by the Muslims, providing dwellings and land, and occasionally the creation of large estates, known as Donadíos.

A series of crises in the 14

th century, the plague, demographic decline in rural areas and increasing urban population, changed the panorama dramatically, resulting in a reduction of

Repartimientos and a growing concentration of lands in the hands of the nobility and a process of

seignorialisation [

20,

21,

22].

In the Modern Era, despite the domination of the Americas, the Spanish economy did not progress, experiencing a difficult transition from feudalism to capitalism.

From the late 16

th century and throughout the 17

th century, the quality of life of the Spanish people suffered, with instances of famine, epidemics (plague and smallpox), resulting in a drop in population, especially in certain agricultural regions. In the Levante, the region would be deprived of important resources with the expulsion of the

Moriscos (1609), a demographic catastrophe causing the rural population to fall by up to 45%. This was in addition to high mortality rates due to war (Thirty Years War, followed by the War of Succession) and growing emigration to America. The result was a severe decline in the Spanish population [

23,

24].

In the 18th century, occasional repopulation efforts were carried out in some uninhabited regions of Spain in need of development or government control.

The first notable experiment in rural repopulation at this time was that of Nuevo Baztán, a colony conceived as a pre-industrial complex by Juan de Goyeneche, undertaken between 1709 and 1713. Imbued with a “Colbertist” spirit, Goyeneche create a company in the form of an urban complex and factory, with over eight hundred workers and various industrial activities, combining repopulation, industry, agriculture and commerce [

25].

A short time later, a project by the king Carlos III,

Nuevas Poblaciones de Sierra Morena y Norte de Andalucía, one of the most ambitious colonisation projects of the Enlightenment era, aiming to create a new and ideal agrarian society, free from the obstacles and burdens of the past. Homes, land, livestock and farming equipment was provided to over 6,000 Catholic colonists from Central Europe, Germany, Switzerland and Flanders [

26].

Under the

Real Cédula para las Nuevas Poblaciones of July 5, 1767, Olavide and Campomanes pursued their fundamental goal of repopulating the empty region between Valdepeñas and Bailén, providing security to a depopulated area plagued by banditry in middle of the

Camino Real de Andalucía between Madrid and Cádiz, the principal port for commerce with the Americas. The project included the construction of new towns:

feligresías or

aldeas, which would spur the development of agriculture and livestock farming,

La Carolina being the most notable example of this effort [

27,

28].

In more recent times, we must mention in relation to the exodus of rural inhabitants to cities the parallel phenomenon, under the Franco regime, of the creation of settlements and colonies in newly incorporated towns to repopulate rural areas.

The

Instituto Nacional de Colonización, created in October 1939 and part of the Ministry of Agriculture, was created to colonise and repopulate the land. Over 300 towns were created in 27 provinces, proving homes and arable land to over 5,000 families, especially in Castilla, Andalucía and Extremadura. The goal was to create planned colonies to repopulate abandoned rural areas and bring dry land into cultivation in specific regions of Spain. These colonies only succeeded, and not always, when accompanied by large-scale irrigation projects [

29].

An analysis of these historical and successive waves of colonisation, depopulation and repopulation in Spain offers important insights into the current challenges facing rural Spain and point the way towards a new model of rural development.

From a historical and sociological point of view, these projects shared a concern for economic diversification, aiming to develop not only agriculture in boosting the rural economy. Agriculture and livestock farming were combined with efforts to develop other industrial and commercial activities connected to the wider economy to reduce traditional dependence on self-sufficiency.

There was also an important effort to attract new settlers from surrounding regions and from abroad, offering economic incentives and opportunities for the newly arrived population.

Furthermore, improvements in infrastructure and basic services were also undertaken to address one of the key factors in depopulation: transportation links, irrigation systems, and quality housing to improve the life of rural inhabitants and attract new residents.

Colonies were connected to active administrative areas or included in more developed administrative structures, fostering public and private cooperative initiatives and community projects to strengthen the economic and social cohesion of these areas.

Equally, the modernisation of agricultural practices and techniques and general rural development more broadly helped these communities adapt to new challenges and opportunities.

3.4. Current Models of Rural Repopulation

The demographic challenges facing a number of regions in Europe are such that Article 174 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, specifically refers to the importance of addressing “disparities between the levels of development of the various regions and the backwardness of the least favoured regions” and “particular attention shall be paid to rural areas (…) and regions which suffer from severe and permanent natural or demographic handicaps” [

49].

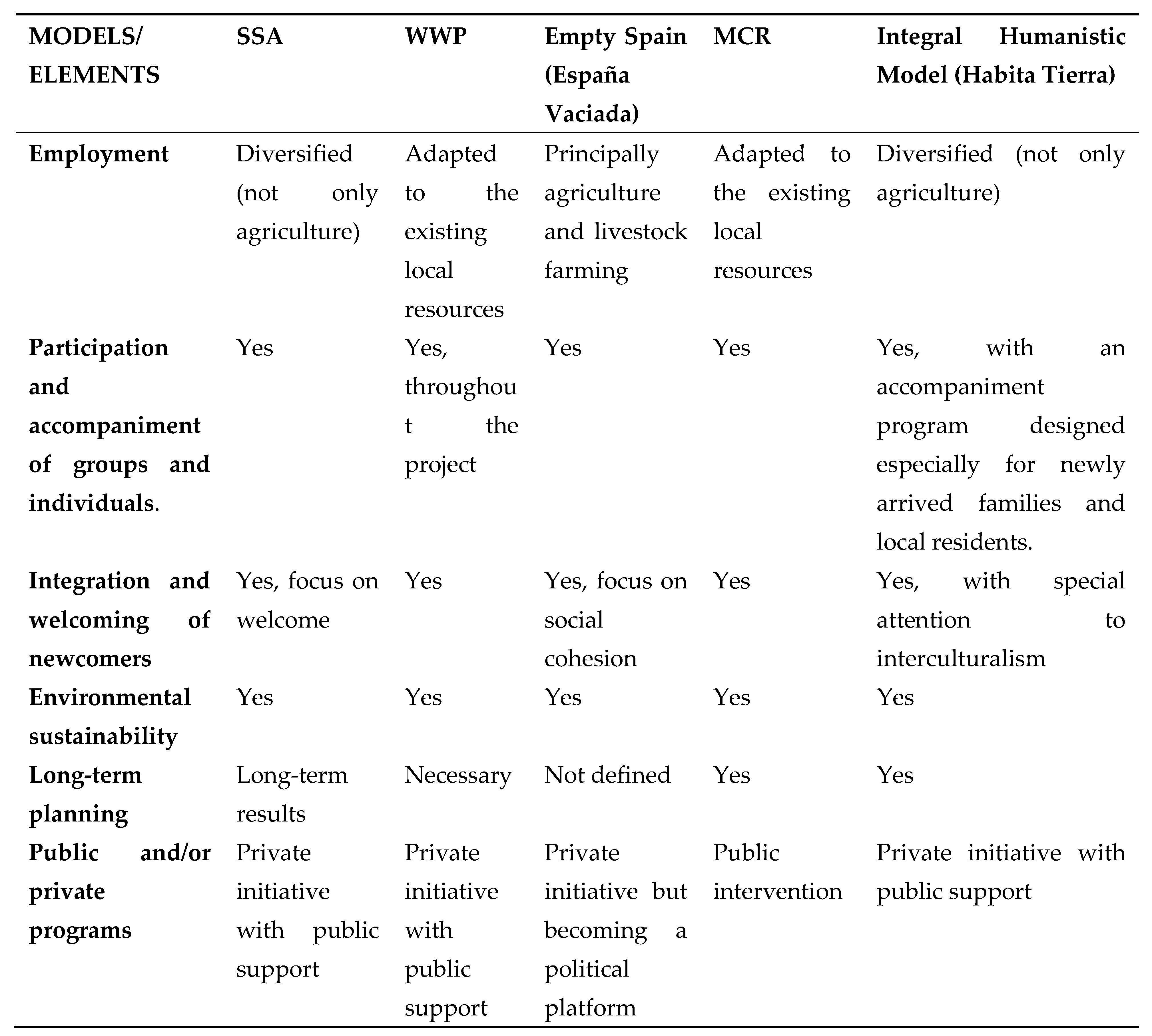

In the following pages we will review the most significant repopulation models based on an examination of literature in Spain as well as international success stories (SSPA and WWP):

The SSPA Network (Southern Sparsely Population Areas) developed a repopulation model in 2017, taking a holistic approach, which was successfully applied in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Another model we will analyse is the WWP (Working With People) rural development and repopulation model, as well as the model developed to address “Empty Spain”, a territorial model created in 2019 as a social movement for regional policy in various regions across Spain. The theoretical rural repopulation model “Compatibility Matrix for Repopulation” was developed in Valle del Genal, in the Spanish province of Málaga [

48] (Ros, 2021). We will conclude with the experience of our own research team: the Habita Tierra repopulation program.

3.4.1. Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Scotland (HIE)

This is part of the TAIEX-REGIO Peer 2 Peer project, facilitating exchange between national and regional entities which manage and administer Regional Development Funds and EU Cohesion Funds.

This model is based on a holistic development project created by the Southern Sparsely Population Areas of Europe (SSPA Network) [

50] in 2017, the first successful model of rural repopulation.

The principal features of the SSPA Network [

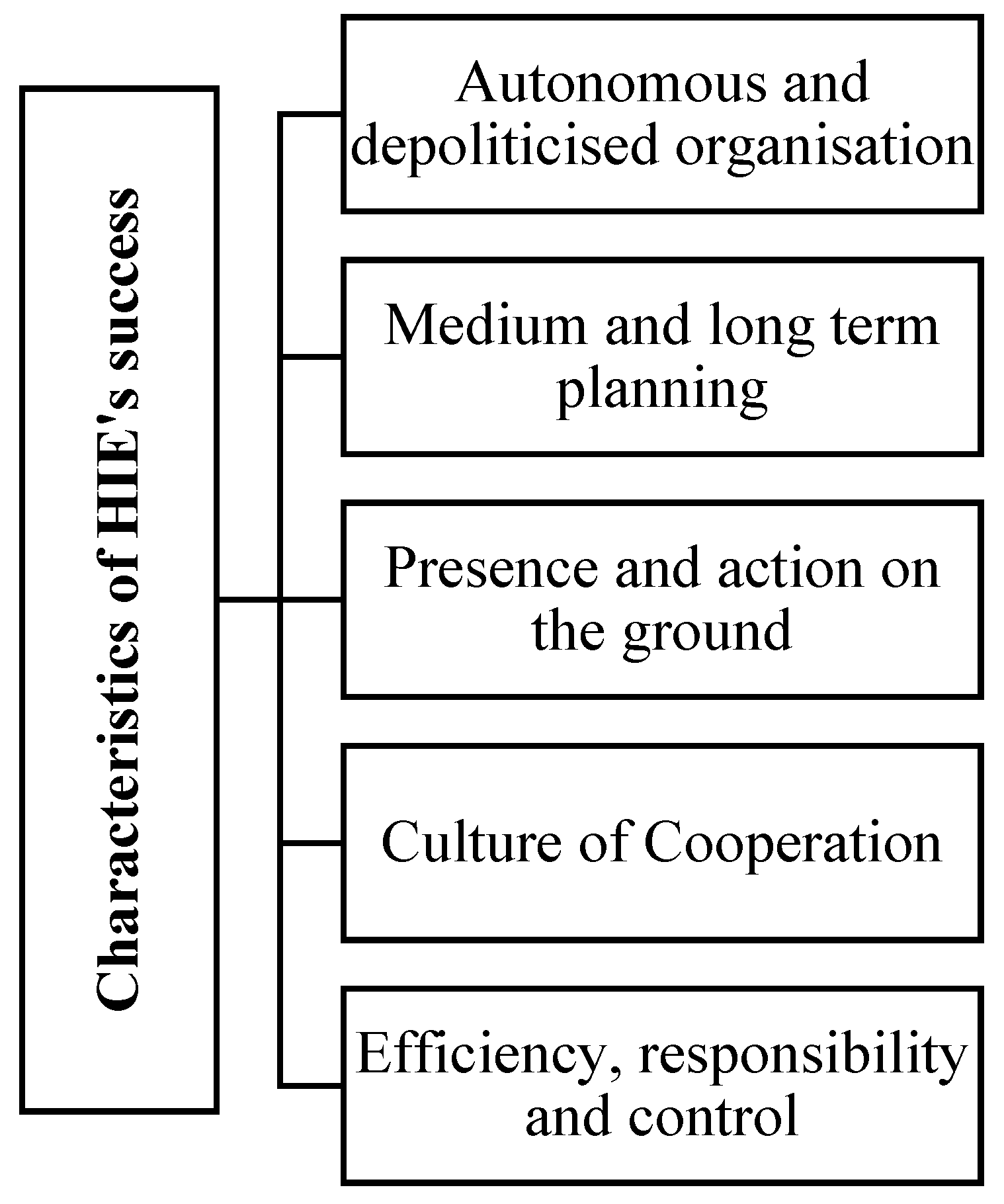

50] which account for the success of the Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Scotland (HIE) are:

Autonomous and depoliticised organisation: this is a publicly funded agency with a board of directors appointed by the corresponding local governments. The agency is wholly autonomous from other public administrations able to develop comprehensive planning initiatives within the territory.

Medium and long-term planning: planning is based on a comprehensive approach, taking into consideration geographical, economic, social, cultural, psychological, and other factors, creating a positive feedback dynamic with a holistic conception of rural development.

Presence and action on the ground: there is direct contact between technical personnel and local residents and collectives who work together to develop the projects, providing first-hand knowledge of local realities; the fact that local residents are empowered to be catalysts for community and/or business development initiatives is an essential aspect of the strategy, fostering a spirit of trust, optimism and entrepreneurial drive.

Culture of cooperation: the HIE is an agency created specifically to promote sustainable development in remote, mountainous and sparsely populated areas with significant structural deficits. From the first, the HIE has acted in cooperation with public institutions as well as private companies, rural communities, schools and research centres, European entities, etc.

Efficiency, responsibility and control: The projects to be funded must be approached from the perspective of their potential impact on economic and social activity of each rural community and its demographics. Appropriate planning and zoning are essential to the success of these projects and the reorganisation of rural areas.

Figure 5.

Characteristics to explain the HIE's success (Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Scotland). Source: the authors, based on SSPA (2017).

Figure 5.

Characteristics to explain the HIE's success (Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Scotland). Source: the authors, based on SSPA (2017).

Any conception of rural development which focusses exclusively on the primary sector is and will continue to be doomed to failure. According to Eurostat, the primary sector accounts for only 2% of the GDP of the EU, and the population living in rural areas is less than 30% and falling. In fact, the poor viability of the primary sector led the HIE to discard it entirely from among its list of the seven sectors for growth which could serve to spur development and economic recovery [

50] (SSPA, 2017).

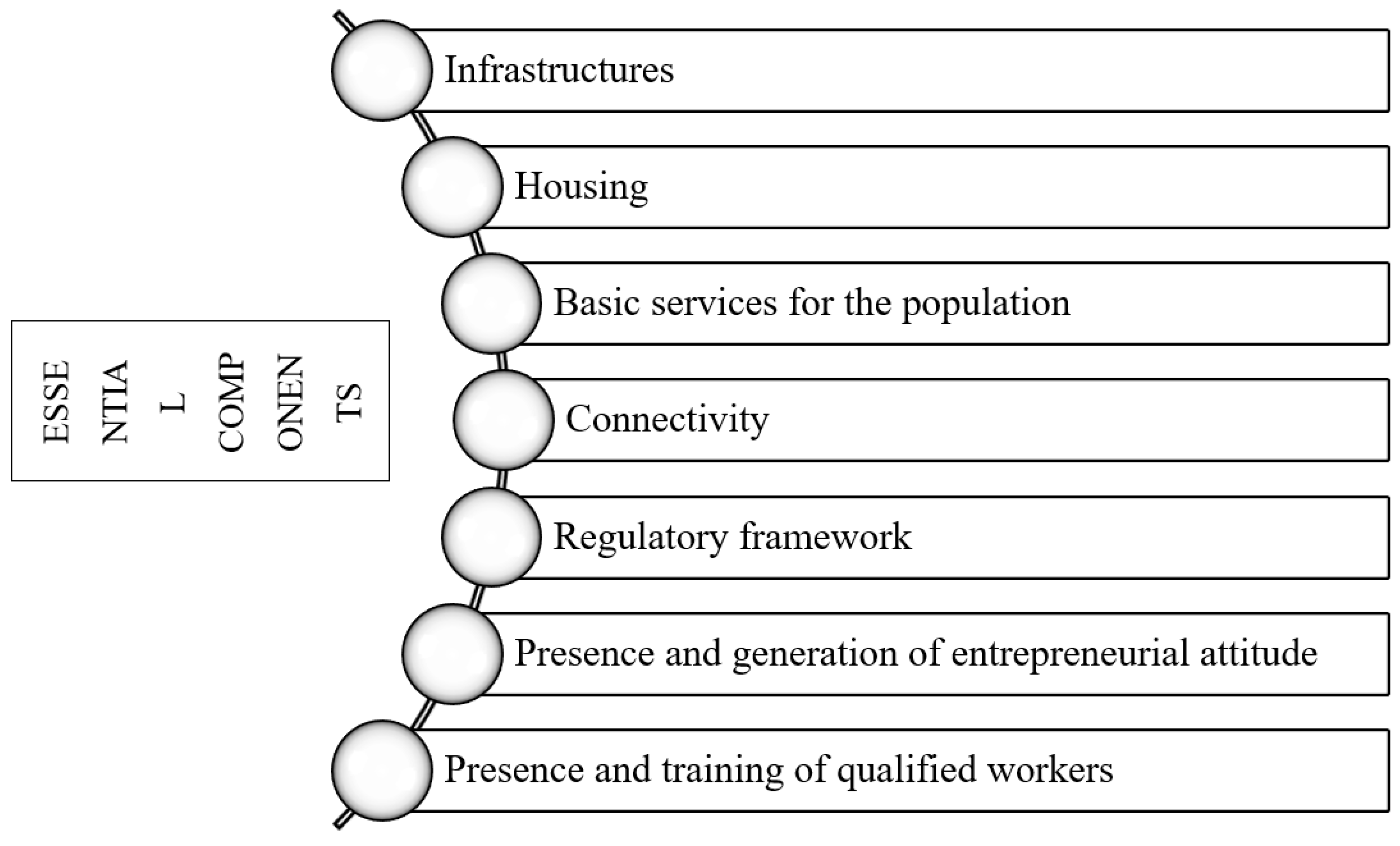

A holistic development model must take into account the following essential components: that there is sufficient infrastructure, basic services and access to essentials; that housing options are both affordable and of sufficient quality; that basic services are available and accessible to serve the local community (education, health and social services, commercial centres or opportunities for cultural or recreational activities, etc.); connectivity and communications (internet and telephony); a regulatory framework that is appropriate and suited to the realities and needs of the rural environment (from local taxation to the exploitation of natural resources); presence and fostering of entrepreneurship (attract and retain talent to create new opportunities); presence of skilled individuals with the ability to attract human capital by offering appealing employment opportunities [

50] (SSPA, 2017).

Figure 6.

Essential components for the Holistic Development model (HIE). Source: the authors, based on SSPA (2017).

Figure 6.

Essential components for the Holistic Development model (HIE). Source: the authors, based on SSPA (2017).

The holistic model of rural development highlights the importance of “ceasing to regard rural life as exclusively associated with farm labour” [

50] (SSPA, 2017). It is important to consider that this is a vast geographical area in which inculcating entrepreneurship, associationism and empowering communities are all fundamental to the prosperity of these regions. All resources must be brought to bear, both material and human, in order to attract new talents and entrepreneurs (especially young people) that can ultimately benefit all of society. In order for a new rural settlement to be successful, it must have easy and rapid access to certain essential elements.

In the successful case of Scotland, the key was the creation of a specialised and independent agency, the reform of local government (reducing the number of municipalities and rationalising the administrative map, improved telecommunications infrastructure, the exploitation of the local economy (in this case, the petrochemical industry, fishing, tourism, etc), and structural funds and subsidies from the European Union. Additionally, it was necessary to analyse the migratory behaviour of young people and take actions to welcome new inhabitants from other parts of the United Kingdom who reversed the trend of population decline.

3.4.2. Working With People, WWP

This is a planning model for rural development which, by promoting the socio-economic development of rural areas, reinforces the options for population settlement. This is a valid model for the planning of rural development, with the beneficiaries participating from the initial design of the plan to its completion. The WWP has been widely studied and validated in different contexts [

51] [

52] where it has proven to be an effective model to boost rural prosperity.

The WWP offers a planning model based on social learning, that is, the participation of local actors throughout the entire process in an experience of continuous and mutual learning, both for planner and for local residents where their knowledge and experience are brought together and shared [

53]. Thus, planners aim to connect knowledge and action in a shared project in which technical expertise works hand in hand with the people involved, valuing their participation and engagement, and judging the success of a project not on its technical sophistication but on its ability to improve the lives of those involved [

54]. This model focusses on the contextual skills and behaviour of people and consists of four phases:

Phase one is institutional architecture, political and contextual, identifies the key actors for the implementation of plans or strategies, including social and political organisations and public institutions, with a subsequent formalisation of agreements and alliances to support implementation.

The two following phases are related to ethical and social dimensions:

Phase two is territorial focus, identifying the beneficiaries and infrastructure, with a socio-economic analysis of the area.

Phase three is the design of a strategic plan; an intervention plan that meets the identified needs of the community. This includes actions to build trust between the local population and institutions by engaging them in the process and being sensitive to the local feelings and concerns.

Finally, phase four is technical-entrepreneurial where the implementation, oversight and evaluation of the plan is carried out.

Figure 7.

Working With People (WWP) Model. Source: Cazorla, A., De los Ríos, I., and Salvo, M. (2013).

Figure 7.

Working With People (WWP) Model. Source: Cazorla, A., De los Ríos, I., and Salvo, M. (2013).

Having implemented the

Working With People program in a number of different rural development projects in various countries, one of its promoters, Ignacio de los Ríos, defines the key element in population resettlement plans: “the scientific basis of the methodology for population recovery is founded on an urban planning tradition called social learning” [

55].

Settlement projects have been the least successful in achieving rural development. The cause of these failures is that these projects overlook or ignore the socio-economic and cultural complexities of new human communities, while also failing to establish a viable and productive economic base for the community [

56].

In depopulated areas, people become the authentic heirs to past traditions and a cultural identity; they feel a duty to safeguard and cultivate this legacy.

It is essential that local inhabitants are welcoming and accepting of newcomers [

57].

Successful settlement of new populations relies on the teamwork of experts in planning and development, as well as specialists in human geography and social sciences given their understanding of community structures and the dynamics of social change.

De los Ríos and Alier [

55] have established a Welcome Plan for depopulated areas which emphasises the importance of carrying out an initial diagnostic or analysis of the following elements:

The physical environment and natural resources.

The local population and population loss.

Socio-economic factors, activities and employment in the area.

Available infrastructure, housing and social services.

Participation of locals: this is a process of listening and learning, involving local inhabitants to dynamise the project.

This diagnostic concludes with:

An inventory and analysis of viable projects with the potential to generate employment.

Identification of the principal barriers to settlement.

Creation a database of potential settlers.

Establishment of criteria for the selection of new settlers.

Analysis of policies, financial support and incentives in each area (for example: tax incentives)

Identification of potential managers of the program.

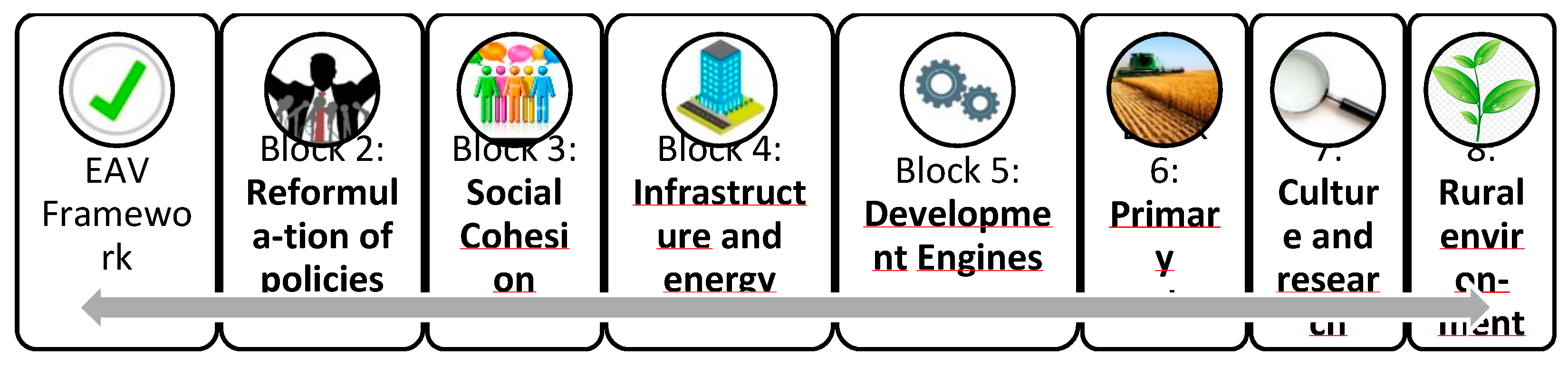

3.4.3. Territorial Planning Model or Empty Spain Model (“España Vaciada”)

This model is based on the need to reverse population decline while finding a sustainable territorial equilibrium.

It is structured and organised to further the territorial cohesion of “Empty Spain” [

58], consisting of eight thematic blocks with 180 components and 82 platforms through Spain.

Figure 8.

Thematic blocks/workshops for Territorial Planning Model. Source: the authors.

Figure 8.

Thematic blocks/workshops for Territorial Planning Model. Source: the authors.

The model is designed for territorial action that can be applied throughout rural Spain, seeking to mobilise social platforms and organisations (which are becoming political movements presenting candidates for elections) and develop new policies in line with the graph above, including:

Prioritise value creation or the evaluation of economic value of each determinant factor in the policies to be applied.

Analysis of regional policies for territorial development to identify areas for innovation or reform.

It is essential to work with local people to build community and social cohesion.

A detailed analysis must be made of the existing infrastructure in the territory, identifying shortcomings, as well as the type of energy available and energy needs for future development.

An analysis of the interrelationship of different elements of the model for the effective coordination of development engines.

An evaluation of the primary sector, that is, agriculture, livestock farming or fishing to evaluate the current challenges and plan for the future.

The cultural development of the rural environment is an important factor in the wellbeing and education of local residents. This model highlights the importance of developing cultural programs and activities for small communities far from large cities. Research is another aspect of the model, contributing to understanding and finding innovative solutions to complex problems in the territory.

The final block is transversal, relating to policies for environmental sustainability and the preservation of biodiversity, factors which are increasingly important in rural development and often conditioned by policies enacted outside the territory or region.

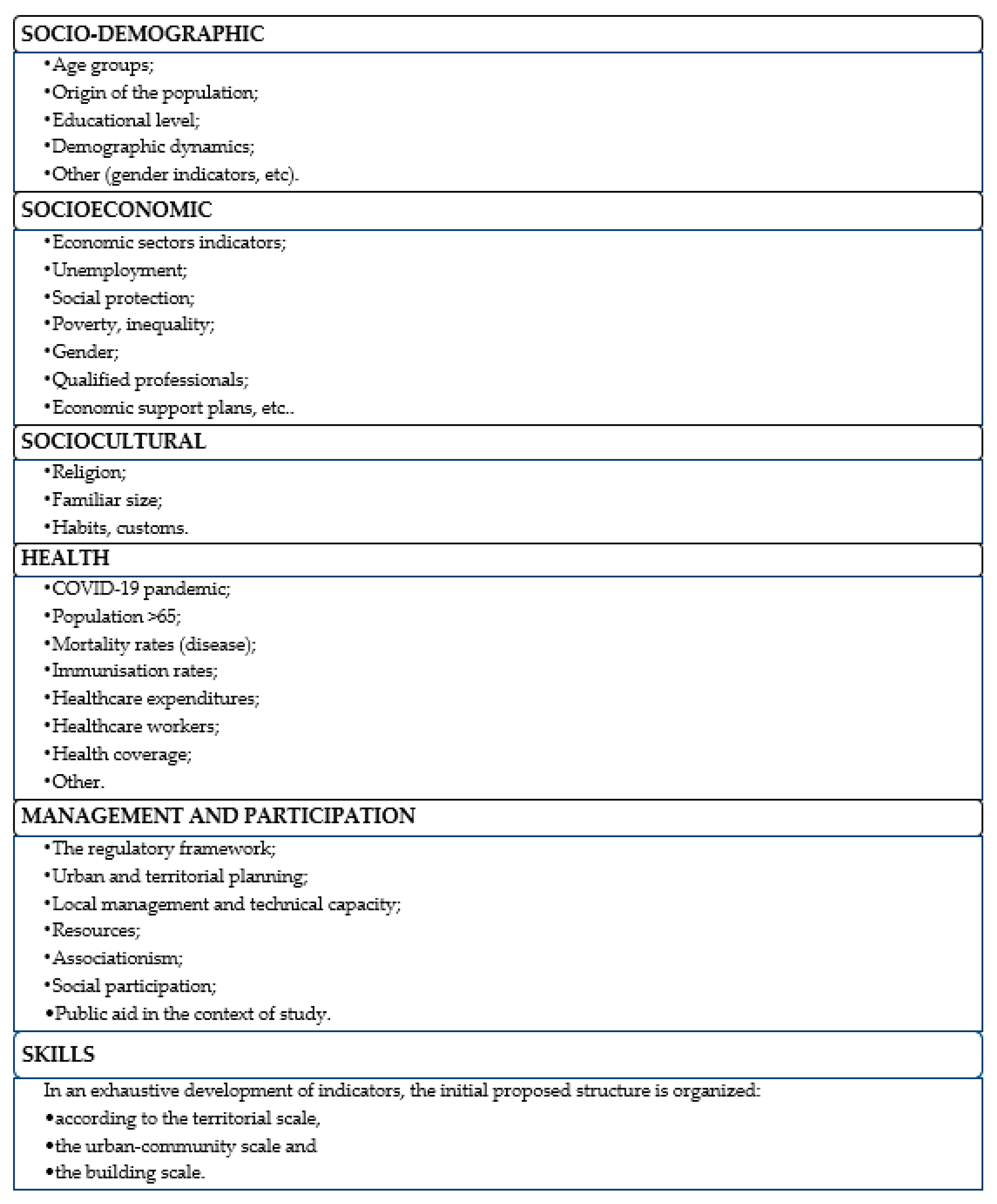

3.4.4. Compatibility Matrix for Repopulation [48]

This research methodology is based on conducting a diagnostic of existing problems and possibilities for intervention to produce the changes Spain requires to face demographic challenges. This is a practical methodology for public administrations to advance strategies and policies which favour sustainable repopulation of rural areas. The goal is to create a territorial model which optimises natural and economic resources while conserving and enhancing environmental, social and cultural capital. This innovative model, the Compatibility Matrix for Repopulation (CMR), combines a quantitative approach with an analysis of qualitative and participatory processes within a specific territory, aiming to identify the compatibility between a territory and specific social groups [

48].

The Compatibility Matrix for Repopulation (CMR) is a scientific tool that permits the characterisation of rural territories at risk of depopulation, identifying its compatibility with a possible influx of new inhabitants.

Figure 9 outlines the key factors studied with this matrix, beginning with socio-demographic factors, the starting point for any repopulation project and considering aspects such as the age and gender of local populations, demographic dynamics and trends, etc.

The matrix examines socioeconomic and sociocultural factors as well as healthcare, management and participation, skills and training, etc. which determine the indicators for various scales of territorial development, urbanisation and construction, etc.

Figure 9.

Key Factors of the Compatibility Matrix for Repopulation. Source: The authors, based on Ros (2021).

Figure 9.

Key Factors of the Compatibility Matrix for Repopulation. Source: The authors, based on Ros (2021).

3.4.5. Habita Tierra: A Humanistic Program for Rural Repopulation

Habita Tierra is a program for inclusive rural repopulation developed by the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria (Madrid) and the Fundación Altius. The program was designed in 2020, incorporating elements which, taken as a whole, facilitate the settlement of immigrant families in depopulated rural areas. The program is currently benefiting from the support of the Spanish Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, registration number REGAGE22e000 24700137.

This applied, person-centred research program analyses the development of a real project underway in the province of Ávila. The key aspects of the project are: the selection of young families with small children seeking to begin a new life in a rural environment, employment options, both in agriculture and other sectors, accompaniment by mentors and professors to help overcome the challenges new residents face, as well as measures to facilitate social integration.

The preliminary results of the program were drawn from surveys and interviews with participating families during the first phase of the Habita Tierra program. The following results were presented at the international Regions in Recovery Congress (March 2022) of the Regional Studies Association (RSA), the Global Conference of Economic Geography (GCEG Dublin, June 2022) and the Nation Congress on Migration (Madrid, September 2022):

The majority of families interested in starting a new life in a rural environment through the Habita Program were immigrants.

The process of integration of new inhabitants in a rural environment takes time. Various families have been participating in the program for over one year and we believe their integration as ‘just another neighbour’ has not yet been achieved.

The program has not identified any significant barriers to integration into the rural environment due to the fact they are immigrants. The children of immigrant families have been welcomed into their schools as any other children, without any reports of incidents of discrimination due to their origins.

Agricultural work requires both skill and vocation, something not everyone possesses. This was confirmed by the participants. Although training was provided, not everyone is suited for this type of work, which is also highly vulnerable to changing weather patterns, drought, etc.

The opportunities for employment in a rural environment are growing, diversifying beyond agriculture and livestock farming. The Habita Tierra program found that the most common, stable employment is found in healthcare, hospitality, construction and services.

Adequate housing and a reliable vehicle were found to be two key factors in successful settlement.

The accompaniment provides to new inhabitants through the program was vitally important. Active listening to the challenges and difficulties these families faced, as well as their successes, served to reinforce their determination and efforts to adapt and integrate into their new environment. The results of the interviews and surveys show that it is vitally important for new inhabitants to have frequent and close contact with external entities to further successful integration.