Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Brand Equity

2.2. Corporate Profitability

2.3. Corporate Governance

3. Methods

3.1. Control Variable Selection

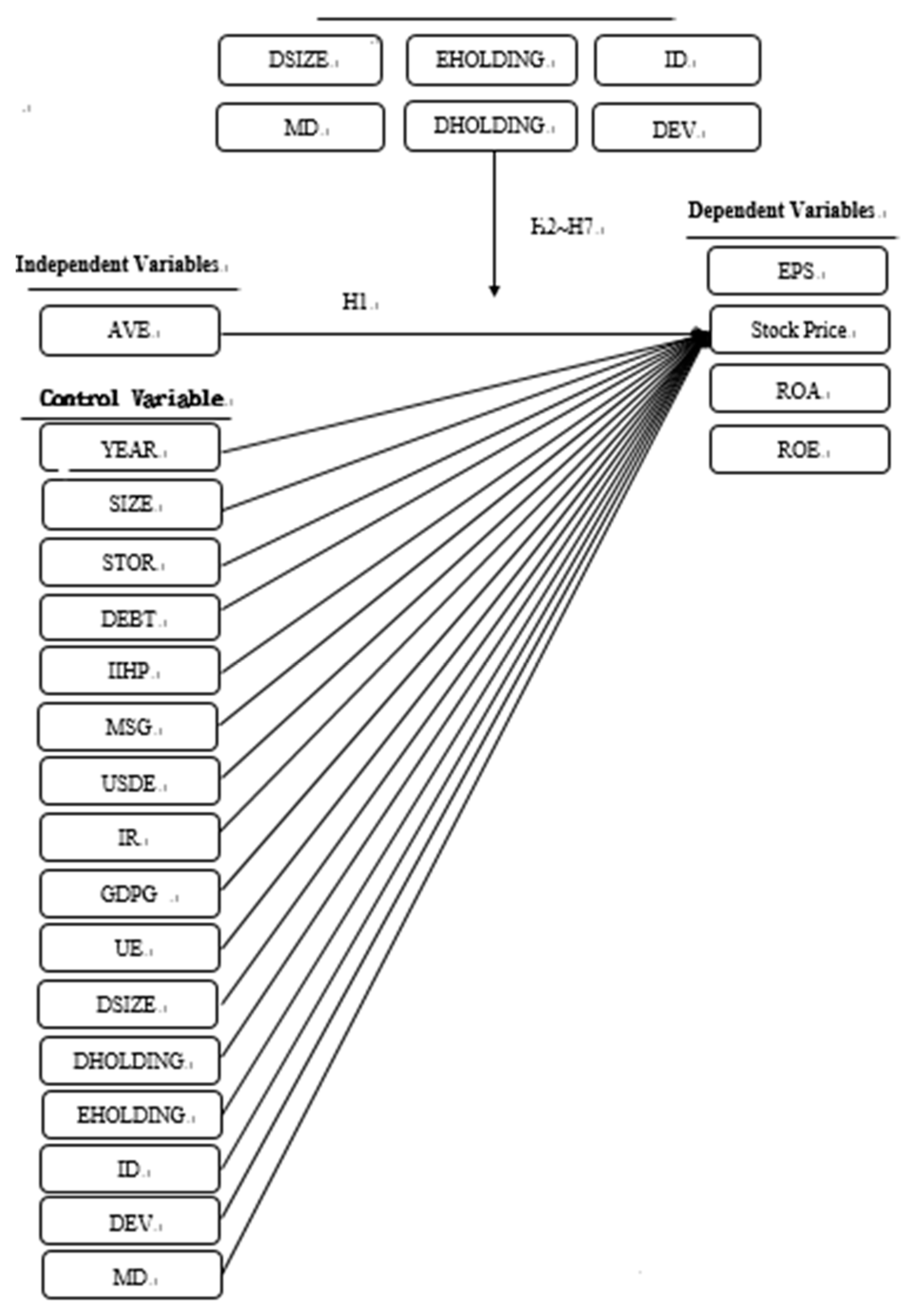

3.2. Research Framework

3.3. Research Subjects and Data Collection

3.4. Research Tools and Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Panel Regression Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion and Managerial Implications

5.1.1. Well-planned advertisement expenditure budget

5.1.2. Reinforcing CG

6. Conclusions

References

- Ambler, T., Bhattacharya, C. B., Edell, J., Keller, K. L., Lemon, K. N., & Mittal, V. (2002). Relating brand and customer perspectives on marketing management. Journal of Service Research, 5(1), 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Brady, M. K., Bourdeau, B. L., & Heskel, J. (2005). The importance of brand cues in intangible service industries: an application to investment services. Journal of Services Marketing, 19(6), 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., Dev, C. S., & Rao, V. R. (2002). Brand extension and customer loyalty: Evidence from the lodging industry. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43(4), 5-16. [CrossRef]

- Kayaman, R., & Arasli, H. (2007). Customer based brand equity: evidence from the hotel industry. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 17(1), 92-109. [CrossRef]

- Leone, R. P., Rao, V. R., Keller, K. L., Luo, A. M., McAlister, L., & Srivastava, R. (2006). Linking brand equity to customer equity. Journal of Service Research, 9(2), 125-138. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. W., & Mittal, V. (2000). Strengthening the satisfaction-profit chain. Journal of Service Research, 3(2), 107-120. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M., Payne, A., & Ballantyne, D. (2013). Relationship marketing: Taylor & Francis.

- Kapferer, J.-N. (1997). Strategic brand management: creating and sustaining brand equity long term, 2. Auflage, London.

- Bharadwaj, S. G., Varadarajan, P. R., & Fahy, J. (1993). Sustainable competitive advantage in service industries: a conceptual model and research propositions. Journal of Marketing, 83-99.

- Madden, T. J., Fehle, F., & Fournier, S. (2006). Brands matter: An empirical demonstration of the creation of shareholder value through branding. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 224-235. [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D. A. (2009). Managing Brand Equity: Simon and Schuster.

- Chaudhuri, A. (2002). How brand reputation affects the advertising-brand equity link. Journal of Advertising Research, 42(3), 33-43. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, K. W., & Hirschey, M. (1993). Advertising, R&D expenditures and the market value of the firm. Financial Management, 128-140. [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N. S., & Sharma, P. (2015). Impact of product differentiation, marketing investments and brand equity on pricing strategies: A brand level investigation. European Journal of Marketing, 49(5/6), 760-781. [CrossRef]

- Eng, L. L., & Keh, H. T. (2007). The effects of advertising and brand value on future operating and market performance. Journal of Advertising, 36(4), 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Jagpal, S. (2008). Fusion for profit: how marketing and finance can work together to create value: Oxford University Press.

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 1-22.

- Wang, M.-C. (2015). Value Relevance of Tobin’s Q and Corporate Governance for the Taiwanese Tourism Industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 223-230. [CrossRef]

- Winters, L. C. (1991). Brand equity measures: some recent advances. Marketing Research, 3(4), 70.

- Chen, C., Chang, C., Wang, L., & Lee, W. (2005). The Ohlson valuation framework and value-relevance of corporate governance: an empirical analysis of the electronic industry in Taiwan. NTU Management Review, 15(2), 123-142.

- Yeh, Y.-H., Lee, T.-S., & Ko, C. (2002). Corporate governance and rating system. Taipei: Sun Bright Co.

- Al-Najjar, B. (2014). Corporate governance, tourism growth and firm performance: Evidence from publicly listed tourism firms in five Middle Eastern countries. Tourism Management, 42, 342-351. [CrossRef]

- Core, J. E., Holthausen, R. W., & Larcker, D. F. (1999). Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 51(3), 371-406. [CrossRef]

- Denis, D. K. (2001). Twenty-five years of corporate governance research… and counting. Review of Financial Economics, 10(3), 191-212. [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2000). Investor protection and corporate governance. Journal of financial economics, 58(1), 3-27. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in management theories. The Academy of Management Executive, 7(1), 81-94. [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P., & Armstrong, G. (2010). Principles of Marketing. Pearson Education.

- Srivastava, R. K., & Shocker, A. D. (1991). Brand equity: a perspective on its meaning and measurement: Marketing Science Institute.

- Pitta, D. A., & Prevel Katsanis, L. (1995). Understanding brand equity for successful brand extension. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 51-64. https://www.msi.org/reports/brand-equity-a-perspec... [CrossRef]

- Feldwick, P. (1996). Do we really need ‘brand equity’? Journal of Brand Management, 4(1), 9-28.

- Hanson, B., Mattila, A. S., O'Neill, J. W., & Kim, Y. (2009). Hotel Rebranding and Rescaling Effects on Financial Performance. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 50(3), 360-370.

- Kapferer, J.-N. (1997). Strategic brand management: creating and sustaining brand equity long term, 2. Auflage, London.

- Leone, R. P., Rao, V. R., Keller, K. L., Luo, A. M., McAlister, L., & Srivastava, R. (2006). Linking brand equity to customer equity. Journal of Service Research, 9(2), 125-138.

- O'Neill, J. W., & Mattila, A. S. (2010). Hotel brand strategy. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 51(1), 27-34.

- Wood, L. (2000). Brands and brand equity: definition and management. Management Decision, 38(9), 662-669. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R., & Ball, S. (2006). An exploration of the meanings of hotel brand equity. Service Industries Journal, 26(1), 15-38. [CrossRef]

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 1-22.

- Winters, L. C. (1991). Brand equity measures: some recent advances. Marketing Research, 3(4), 70.

- Chaudhuri, A. (2002). How brand reputation affects the advertising-brand equity link. Journal of Advertising Research, 42(3), 33-43.

- Davcik, N. S., & Sharma, P. (2015). Impact of product differentiation, marketing investments and brand equity on pricing strategies: A brand level investigation. European Journal of Marketing, 49(5/6), 760-781.

- Eng, L. L., & Keh, H. T. (2007). The effects of advertising and brand value on future operating and market performance. Journal of Advertising, 36(4), 91-100.

- Wang, M.-C. (2013). Value relevance on intellectual capital valuation methods: the role of corporate governance. Quality & Quantity, 47(2), 1213-1223. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. W. (2003). ADR rule of thumb validity and suggestions for its application. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 7-16. [CrossRef]

- Oak, S., & Dalbor, M. C. (2010). Do institutional investors favor firms with greater brand equity? An empirical investigation of investments in US lodging firms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(1), 24-40.

- Fox, D. R., & McCully, C. P. (2009). Concepts and methods of the US national income and product accounts. NIPA Handbook.

- O'Neill, Saunders, C. B., & McCarthy, A. D. (1989). Board members, corporate social responsiveness and profitability: Are tradeoffs necessary? Journal of Business Ethics, 8(5), 353-357.

- Zahra, S. A., & Stanton, W. W. (1988). The implications of board of directors composition for corporate strategy and performance. International Journal Of Management, 5(2), 229-236.

- Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28(2), 446-463.

- Khan, Z. H., Alin, T. S., & Hussain, M. A. (2011). Price prediction of share market using artificial neural network (ANN). International Journal of Computer Applications, 22(2), 42-47. [CrossRef]

- Nizar Al-Malkawi, H.-A. (2007). Determinants of corporate dividend policy in Jordan: an application of the Tobit model. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 23(2), 44-70.

- Madden, T. J., Fehle, F., & Fournier, S. (2006). Brands matter: An empirical demonstration of the creation of shareholder value through branding. Journal of The Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 224-235.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (2002). Investor protection and corporate valuation. Journal of finance, 1147-1170. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.-F., Roll, R., & Ross, S. A. (1986). Economic forces and the stock market. Journal of Business, 383-403. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A., & Knoeber, C. R. (1996). Firm performance and mechanisms to control agency problems between managers and shareholders. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 31(03), 377-397. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., & Peters, G. F. (2004). Audit committee characteristics and restatements. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(1), 69-87. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, T., Sundgren, S., & Wells, M. T. (1998). Larger board size and decreasing firm value in small firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 48(1), 35-54. [CrossRef]

- Yermack, D. (1996). Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. Journal Of Financial Economics, 40(2), 185-211. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. S., & Duellman, S. (2007). Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43(2), 411-437. [CrossRef]

- Vafeas, N. (2005). Audit committees, boards, and the quality of reported earnings. Contemporary accounting research, 22(4), 1093-1122. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, K. (1997). Intellectual capital and the new wealth of nations. Business Strategy Review, 8(1), 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360. [CrossRef]

- Crutchley, C. E., Garner, J. L., & Marshall, B. B. (2002). An examination of board stability and the long-term performance of initial public offerings. Financial Management, 63-90. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. S. (1983). The market for corporate control: The scientific evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 11(1), 5-50. [CrossRef]

- Fang, V. W., Tian, X., & Tice, S. (2014). Does stock liquidity enhance or impede firm innovation? Journal of Finance, 69(5), 2085-2125.

- Demsetz, H., & Lehn, K. (1985). The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1155-1177. [CrossRef]

- Su, K., Li, L., & Wan, R. (2017). Ultimate ownership, risk-taking and firm value: evidence from China. Asia Pacific Business Review, 23(1), 10-26. [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., Fan, J. P., & Lang, L. H. (2002). Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2741-2771. [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C., Nanda, D., & Wysocki, P. D. (2003). Earnings management and investor protection: an international comparison. Journal of Financial Economics, 69(3), 505-527. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. W., & Xiao, Q. (2006). The role of brand affiliation in hotel market value. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 47(3), 210-223.

- Datar, V. T., Naik, N. Y., & Radcliffe, R. (1998). Liquidity and stock returns: An alternative test. Journal of Financial Markets, 1(2), 203-219. [CrossRef]

- Gligor, M., & Ausloos, M. (2008). Convergence and cluster structures in EU area according to fluctuations in macroeconomic indices. Journal of Economic Integration, 297-330. [CrossRef]

- Kandir, S. Y. (2008). Macroeconomic variables, firm characteristics and stock returns: evidence from Turkey. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 16(1), 35-45.

- Singh, T., Mehta, S., & Varsha, M. (2011). Macroeconomic factors and stock returns: Evidence from Taiwan. Journal Of Economics And International Finance, 3(4), 217.

- Razali, N. M., & Wah, Y. B. (2011). Power comparisons of shapiro-wilk, kolmogorov-smirnov, lilliefors and anderson-darling tests. Journal Of Statistical Modeling and Analytics, 2(1), 21-33.

- Ahn, S. C., & Low, S. (1996). A reformulation of the Hausman test for regression models with pooled cross-section-time-series data. Journal of Econometrics, 71(1), 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econometrica. 46 (6): 1251–1271. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A., & Nakamura, M. (1981). On the relationships among several specification error tests presented by Durbin, Wu, and Hausman. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 1583-1588. [CrossRef]

- Brickey, K. F. (2003). From Enron to WorldCom and beyond: Life and crime after Sarbanes-Oxley. Washington University Law Quarterly, 81.

- Roychowdhury, S. (2006). Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 335-370. [CrossRef]

| Year | Researcher | Definition | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Srivastava and Shocker[28] | BE is the aggregation of all accumulated attitudes and behavior patterns in the extended minds of consumers, distribution channels and influence agents, which will enhance future profits and long-term cash flow | Brand name and label were not taken into account. |

| 1991 | Winters[19] | BE involves the value added to a product by consumers' associations and perceptions of a particular brand name | Price was taken into account and involved in the measurement of BE. |

| 1993 | Keller[17] | BE represents a condition in which the consumer is familiar with the brand and recalls all associations with the brand, such as label color scheme, brand values, jingle, and even purchase experience. | A consumer-centered definition was proposed. |

| 1995 | Pitta and Katsanis[29] | BE increases the probability of brand choice, leads to brand loyalty, and insulates the brand from a measure of competitive threats. | Market competition was taken into account. |

| 1996 | Feldwick[30] |

|

The definition of BE was simplified and categorized. |

| 2006 | Bailey and Ball[36] | The BE of hotels is the associative value between brands and customers/hotel owners, the effects of these associations on customers/hotel owners and subsequent financial performance of the brand. | A definition of BE in hotel industry was proposed. |

| 2009 | Aaker[11] | BE is a multidimensional concept that includes brand loyalty, brand awareness, perceived quality, brand associations, and other related brand assets. | This is currently the most complete and widely used definition. |

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPS (NTD) | -6.94 | 15.69 | 1.59 | 3.77 |

| Stock Price (NTD) | 2.41 | 1875.63 | 89.10 | 186.24 |

| ROA (%) | -53.76 | 22.92 | 2.14 | 12.66 |

| ROE (%) | -156.95 | 67.28 | 1.03 | 27.89 |

| AVE (NTD) | .00 | 8893598.00 | 507720.91 | 1351807.57 |

| Year (NTD) | 2.00 | 58.00 | 28.07 | 14.29 |

| SIZE | 11.74 | 16.32 | 14.44 | 1.04 |

| DEBT (%) | 7.59 | 86.48 | 39.21 | 18.16 |

| STOR (%) | .75 | 2611.69 | 112.52 | 218.46 |

| IIHP (%) | .00 | 87.88 | 41.60 | 25.43 |

| MSG (%) | -4.12 | 20.47 | 7.70 | 4.86 |

| IR (%) | -.07 | 16.53 | 10.12 | 6.05 |

| GDPG (%) | -1.57 | 10.63 | 3.48 | 2.97 |

| UE (%) | 2.99 | 5.85 | 4.30 | .60 |

| USDE (NTD) | 29.46 | 34.58 | 31.67 | 1.59 |

| DSIZE (people) | 3.00 | 16.00 | 6.89 | 2.70 |

| DHOLDING (%) | .16 | 67.87 | 25.10 | 14.45 |

| EHOLDING (%) | .00 | 53.86 | 16.35 | 11.33 |

| ID (%) | .00 | 60.00 | 12.99 | 17.69 |

| DEV (%) | .00 | 35.01 | 3.60 | 6.98 |

| MD (%) | .00 | 75.00 | 18.04 | 14.24 |

| DSIZE×AVE | .00 | 78809004.00 | 4462570.35 | 12414209.96 |

| DHOLDING×AVE | .00 | 411862523.38 | 14964438.82 | 52087607.02 |

| EHOLDING×AVE | .00 | 230344188.20 | 9610816.02 | 29840041.24 |

| ID×AVE | .00 | 444679900.00 | 14886405.04 | 53704949.44 |

| DEV×AVE | .00 | 179997186.40 | 5958092.17 | 24635207.22 |

| MD×AVE | .00 | 444679900.00 | 13750456.87 | 51756351.40 |

| Coefficients | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| DV | EPS | Stock Price | ROA | ROE |

| AVE | 4.71e-06 * | 5.84e-05 | -7.76e-06 | -2.54e-05 |

| YEAR | .206 | 25.819 * | 1.327 | 4.890 * |

| SIZE | 159.136*** | 125.183 *** | 5.537 *** | 13.194 *** |

| DEBT | -.004 | -1.636 *** | -.153 *** | -.808 *** |

| STOR | .003 *** | -.015 | .017 *** | .517 *** |

| IIHP | .032 | 5.521 *** | .321 *** | .673 *** |

| MSG | -.023 | -1.773 | -.074 | -.111 |

| IR | -.089 | -24.854 * | -1.368 | -4.495 ** |

| GDPG | .040 | 2.219 | -.155 | -.646 |

| UE | -.230 | -32.472 | -1.999 | -7.713 ** |

| USDE | -.110 | .777 | -1.317 | -2.578 |

| DSIZE | .465 ** | 13.046 | -.029 | -2.112 |

| DHOLDING | .023 | .670 | .309 *** | .410 * |

| EHOLDING | -.002 | -2.825 * | .061 | .202 |

| ID | .010 | -4.110 ** | .073 | .030 |

| DEV | -.001 | -1.623 | .350 | 1.143 |

| MD | .021 | -.803 | .062 | .102 |

| DSIZE×AVE | -6.09e-07 *** | 1.06e-06 | 1.41e-06 | 5.22e-06 * |

| DHOLDING×AVE | 6.74e-08 * | -7.35e-06 * | -4.15e-07 * | -9.43e-07 |

| EHOLDING×AVE | -2.47e-08 | -1.20e-06 | -2.44e-08 | -4.90e-07 |

| ID×AVE | 1.24e-07 * | 6.96e-07 | -6.54e-08 | -5.67e-09 |

| DEV×AVE | -8.59e-08 ** | -3.49e-06 | -6.45e-07 ** | -1.65e-06 ** |

| MD×AVE | -6.85e-07 | 4.62e-06 * | 3.63e-07 ** | 8.80e-07 ** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.051 | 0.046 |

| Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| DV | EPS | Stock Price | ROA | ROE |

| AVE | + | Ns | ns | ns |

| YEAR | ns | + | ns | + |

| SIZE | + | + | + | + |

| DEBT | ns | - | - | - |

| STOR | + | Ns | + | + |

| IIHP | ns | + | + | + |

| MSG | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| IR | ns | - | ns | - |

| GDPG | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| UE | ns | ns | ns | - |

| USDE | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| DSIZE | + | ns | ns | ns |

| DHOLDING | ns | ns | + | + |

| EHOLDING | ns | - | ns | ns |

| ID | ns | - | ns | ns |

| DEV | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| MD | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| DSIZE×AVE | - | ns | ns | + |

| DHOLDING×AVE | + | - | - | ns |

| EHOLDING×AVE | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| ID×AVE | + | ns | ns | ns |

| DEV×AVE | - | ns | - | - |

| MD×AVE | ns | + | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).