Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Development of the Brigada Digital Model and Collaborators.

Brigada Digital Member Role Development, Recruitment, and Training.

Theoretical Basis and Messaging Strategies.

Culturally- and Contextually-Tailored Content, Formats, and Accessibility.

Implementation Process – Content Development, Dissemination, and Audience Engagement.

Data Collection and Analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Content Overview.

3.2. Brigada Digital Audience, Reach and Engagement.

3.3. Brigada Digital’s Most Engaging Content.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paz MI, Marino-Nunez D, Arora VM, Baig AA. Spanish Language Access to COVID-19 Vaccination Information and Registration in the 10 Most Populous Cities in the USA. J GEN INTERN MED. 2022, 37, 2604–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeke J, Ramos SR, McFadden SM, et al. Strategies That Promote Equity in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake for Latinx Communities: a Review. J Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, Published online May 6. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Garcini LM, Ambriz AM, Vázquez AL, et al. Vaccination for COVID-19 among historically underserved Latino communities in the United States: Perspectives of community health workers. Front Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Perez A, Johnson JK, Marquez DX, et al. Factors related to COVID-19 vaccine intention in Latino communities. Page K, ed. PLoS ONE, 2022; 17, e0272627. [CrossRef]

- Equitable Access To Health Information For Non-English Speakers Amidst The Novel Coronavirus Pandemic. Published online , 2020. 2 April. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Aguinaga B, Oaxaca AL, Barreto MA, Sanchez GR. Spanish-Language News Consumption and Latino Reactions to COVID-19. IJERPH. 2021, 18, 9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher C, Bragard E, Madhivanan P. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Economically Marginalized Hispanic Parents of Children under Five Years in the United States. Vaccines. 2023, 11, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandric A, Anderson HI, Melcher S, Nilizadeh S, Wilson GM. Spanish Facebook Posts as an Indicator of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Texas. Vaccines. 2022, 10, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman J, Ognyanova K, Baum M, et al. The Role of Race, Religion, and Partisanship in Misinformation about COVID-19. Northwestern Institute for Policy Research. 2020;WP-20-38. Accessed March 16, 2023. /. Available online: https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/working-papers/2020/wp-20-38.pdf.

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Maloney E, et al. Psychosocial Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Intention Among White, Black, and Hispanic Adults in the US. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2022, 56, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Granillo C, Peteet B, et al. Rapid Implementation of a Community–Academic Partnership Model to Promote COVID-19 Vaccine Equity within Racially and Ethnically Minoritized Communities. Vaccines. 2022, 10, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finset A, Bosworth H, Butow P, et al. Effective health communication – a key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Education and Counseling. 2020, 103, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause NM, Freiling I, Beets B, Brossard D. Fact-checking as risk communication: the multi-layered risk of misinformation in times of COVID-19. Journal of Risk Research, 1: , 2020, 22 April 2020. [CrossRef]

- Abrams EM, Greenhawt M. Risk Communication During COVID-19. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2020, 8, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohiniva AL, Sane J, Sibenberg K, Puumalainen T, Salminen M. Understanding coronavirus disease (COVID-19) risk perceptions among the public to enhance risk communication efforts: a practical approach for outbreaks, Finland, February 2020. Eurosurveillance, 2020; 25. [CrossRef]

- Silesky MD, Panchal D, Fields M, et al. A Multifaceted Campaign to Combat COVID-19 Misinformation in the Hispanic Community. J Community Health, Published online November 18,. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mochkofsky G. The Latinx Community and COVID-Disinformation Campaigns Researchers debate how best to counter false narratives—and racial stereotypes. The New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-latinx-community-and-covid-disinformation-campaignsPublished January 14, 2022.

- Longoria J, Acosta D, Urbani S, Smith R. A Limiting Lens: How Vaccine Misinformation Has Influenced Hispanic Conversations Online. Social Science Research Council. Available online: https://mediawell.ssrc.org/news-items/a-limiting-lens-how-vaccine-misinformation-has-influenced-hispanic-conversations-online-first-draft/Published December 8, 2021.

- Herrera-Peco I, Jiménez-Gómez B, Peña Deudero JJ, Benitez De Gracia E, Ruiz-Núñez C. Healthcare Professionals’ Role in Social Media Public Health Campaigns: Analysis of Spanish Pro Vaccination Campaign on Twitter. Healthcare. 2021, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul K. “Facebook Has a Blind Spot”: Why Spanish-Language Misinformation Is Flourishing. The Guardian; 2021. Accessed May 16, 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/mar/03/facebook-spanish-language-misinformation-covid-19-election.

- Acevedo N. Latinos More Likely to Get, Consume and Share Online Misinformation, Fake News. NBC News; 2021. Accessed May 16, 2023. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/latinos-likely-get-consume-share-onlinemisinformation-fake-news-rcna2622.

- Roozenbeek J, Schneider CR, Dryhurst S, et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R Soc open sci. 2020, 7, 201199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Mas F, Jacobson HE. Advancing Health Literacy Among Hispanic Immigrants: The Intersection Between Education and Health. Health Promotion Practice. 2019, 20, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammel L, Artiga S, Safarour A, Stokes M, Brodie M. COVID-19 Vaccine Access, Information, and Experiences Among Hispanic Adults in the U.S. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. Accessed March 20, 2023. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-access-information-experiences-hispanic-adults/.

- Longoria J, Acosta D, Urbani S, Smith R. A Limiting Lens: How Vaccine Misinformation Has Influenced Hispanic Conversations Online. First Draft News Accessed May 16, 2023. Available online: https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/COVID-19_VACCINE_MISINFORMATION_HISPANIC_COMMUNITIES.pdf?x21167.

- Jennings W, Stoker G, Bunting H, et al. Lack of Trust, Conspiracy Beliefs, and Social Media Use Predict COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba S, de Figueiredo A, Piatek SJ, de Graaf K, Larson HJ. Measuring the Impact of Exposure to COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Vaccine Intent in the UK and US, Public and Global Health. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Neely S, Eldredge C, Sanders R. Health Information Seeking Behaviors on Social Media During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among American Social Networking Site Users: Survey Study. J Med Internet Res, 2021; 23, e29802. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith LP, Rowland-Pomp M, Hanson K, et al. Use of social media platforms by migrant and ethnic minority populations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 0618. [CrossRef]

- Muric G, Wu Y, Ferrara E. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy on Social Media: Building a Public Twitter Data Set of Antivaccine Content, Vaccine Misinformation, and Conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill, 2021; 7, e30642. [CrossRef]

- Zhu H, Liu K. Capturing the Interplay between Risk Perception and Social Media Posting to Support Risk Response and Decision Making. IJERPH. 2021, 18, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni YA, et al. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review of the literature. eClinicalMedicine, 2022; 48, 101454. [CrossRef]

- Peretz PJ, Islam N, Matiz LA. Community Health Workers and Covid-19 — Addressing Social Determinants of Health in Times of Crisis and Beyond. N Engl J Med, 2020; 383, e108. [CrossRef]

- Munoz C, Rodriguez A. Supporting Hispanic community leaders to increase COVID-19 vaccination. New America. Available online: https://www.newamerica.org/new-practice-lab/blog/supporting-hispanic-community-leaders-to-increase-covid-19-vaccination/Published July 14, 2021. Accessed May 16, 2023.

- Mitchell K. GW Students Mobilize to Counter COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media. GW Today. Available online: https://gwtoday.gwu.edu/gw-students-mobilize-counter-covid-19-misinformation-social-mediaPublished July 8, 2021. Accessed June 16, 2023.

- Pregúntale al Dr. Huerta: Contesta todas tus preguntas sobre el coronavirus y el proceso en el desarrollo de las vacunas y su efectividad ante una posible mutación del virus. CNN en español; 2020. Accessed May 8, 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=isO70uLkk70.

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edberg M, Krieger L. Recontextualizing the social norms construct as applied to health promotion. SSM - Population Health, 2020; 10, 100560. [CrossRef]

- Davila YR, Reifsnider E, Pecina I. Familismo: influence on Hispanic health behaviors. Applied Nursing Research, 2011; 24, e67–e72. [CrossRef]

- Diaz CJ, Niño M. Familism and the Hispanic Health Advantage: The Role of Immigrant Status. J Health Soc Behav. 2019, 60, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivieso-Mora E, Peet CL, Garnier-Villarreal M, Salazar-Villanea M, Johnson DK. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Familism and Mental Health Outcomes in Latino Population. Front Psychol, 2016; 7. [CrossRef]

- García AA, Zuñiga JA, Lagon C. A Personal Touch: The Most Important Strategy for Recruiting Latino Research Participants. J Transcult Nurs. 2017, 28, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magaña, D. Local Voices on Health Care Communication Issues and Insights on Latino Cultural Constructs. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2020, 42, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangcharoensathien V, Calleja N, Nguyen T, et al. Framework for Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Methods and Results of an Online, Crowdsourced WHO Technical Consultation. J Med Internet Res, 2020; 22, e19659. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. How to Fight an Infodemic: The Four Pillars of Infodemic Management. J Med Internet Res, 2020; 22, e21820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarron E, Oyeyemi SO, Wynn R. COVID-19-related misinformation on social media: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 455–463A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Mas F, Jacobson HE. Advancing Health Literacy Among Hispanic Immigrants: The Intersection Between Education and Health. Health Promotion Practice. 2019, 20, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Mas F, Jacobson HE, Olivárez A. Adult Education and the Health Literacy of Hispanic Immigrants in the United States. Journal of Latinos and Education. 2017, 16, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson HE, Hund L, Soto Mas F. Predictors of English Health Literacy among U.S. Hispanic Immigrants: The importance of language, bilingualism and sociolinguistic environment. LNS. 2016, 24, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canva. Available online: https://www.canva.com/Accessed Accessed July 6, 2023, 2023.

- Trello. Available online: https://www.trello.com/.

- Seeger MW, Pechta LE, Price SM, et al. A Conceptual Model for Evaluating Emergency Risk Communication in Public Health. Health Security. 2018, 16, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeger, MW. Best Practices in Crisis Communication: An Expert Panel Process. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2006, 34, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray RJ, Becker SM, Henderson N, et al. Communicating With the Public About Emerging Health Threats: Lessons From the Pre-Event Message Development Project. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia E, Lin L, Viswanath K. Communications in Public Health Emergency Preparedness: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science. 2013, 11, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Metrics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | -- | Number of accounts that saw a post, story, or ad at least once (organic and paid) | Number of accounts that saw a post, story, or ad at least once (organic and paid) |

| Impressions | Number of times a tweet was seen |

Number of times a post was seen (organic and paid) |

Number of times a post was seen (organic and paid) |

| Post Engagement | Sum of likes, replies, retweets, 2-sec media views, detail expands, profile clicks, hashtag clicks, link clicks, and new followers gained |

Sum of post shares, reactions, saves, comments, likes, interactions, 3-sec video plays, photo views, and link clicks while ad is running | Sum of post shares, reactions, saves, comments, likes, interactions, 3-sec video plays, photo views, and link clicks while ad is running |

| Likes/ Reactions | Number of tweet likes | Number of post likes | Number of post likes |

| Comments/Replies | Number of tweet replies | Number of post comments | Number of post comments |

| Shares/Retweets | Number of retweets | Number of shares to timelines, groups, or pages | Number of shares |

| Video thru plays | -- | Number of times video was played to completion, or for at least 15 seconds |

Number of times video was played to completion, or for at least 15 seconds |

| Detail Expands | Number of clicks on tweet to view more details | -- | -- |

| Page/Profile Visits |

Number of profile visits | Number of page visits | Number of profile visits |

| Link Clicks | Number of link clicks in tweet | Number of link click in post |

Number of link click in post |

| Post Topic | Posts with Primary Topic (N) |

Posts with Secondary Topic (N) |

Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brigada Promotion | 8 | 0 | 8 (2.18%) |

| COVID Science & Variants | 4 | 43 | 47 (12.84%) |

| Masking | 9 | 9 | 18 (4.92%) |

| Multi-prevention | 1 | 8 | 9 (2.46%) |

| Non-COVID | 19 | 0 | 19 (5.19%) |

| COVID - Pregnancy/Breastfeeding | 1 | 4 | 5 (1.37%) |

| COVID Risk Communication | 69 | 1 | 70 (19.12%) |

| Social Distancing/Air Quality | 1 | 2 | 3 (0.82%) |

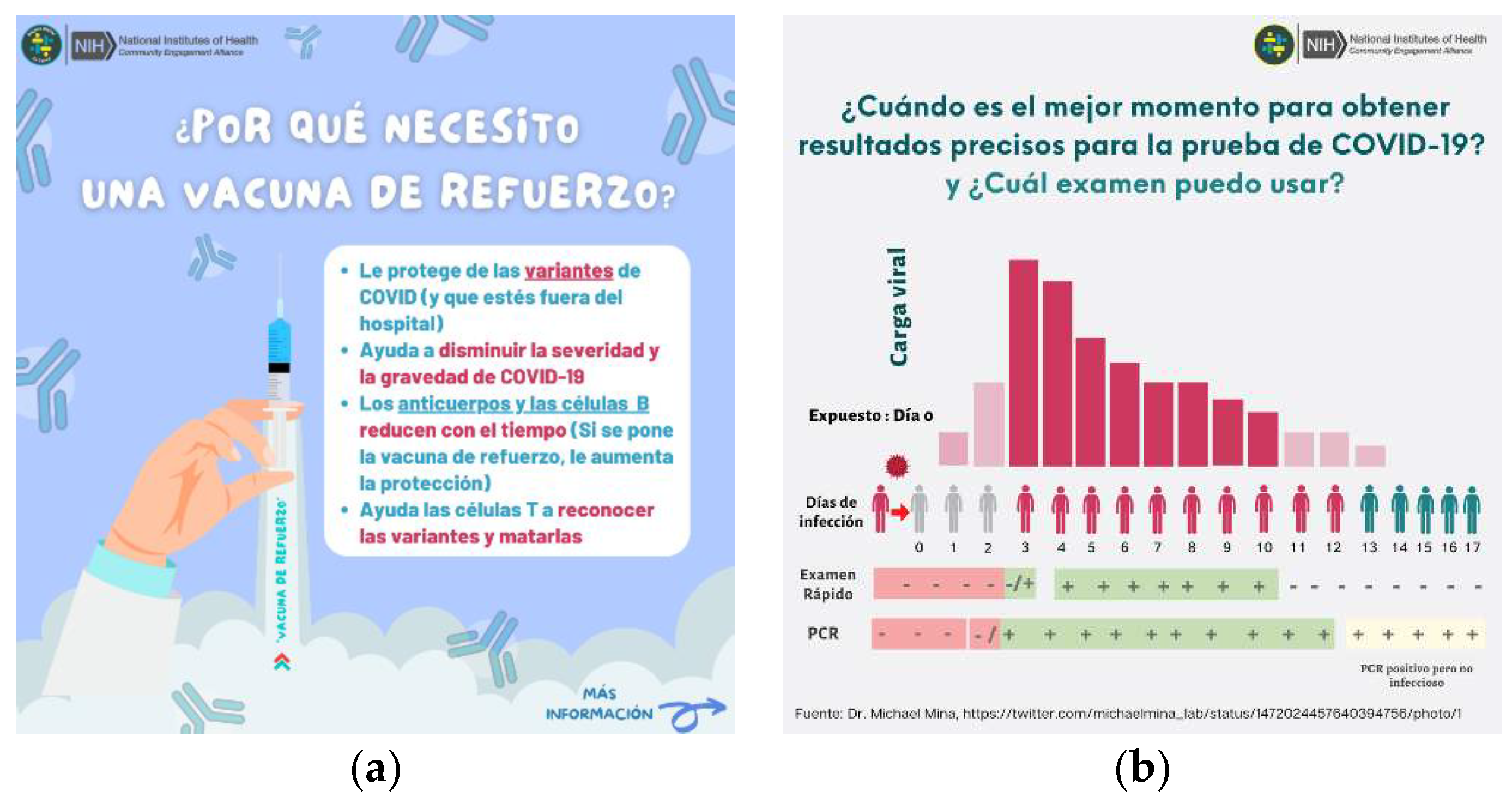

| COVID Testing | 5 | 1 | 6 (1.64%) |

| COVID Boosters | 9 | 13 | 22 (6.01%) |

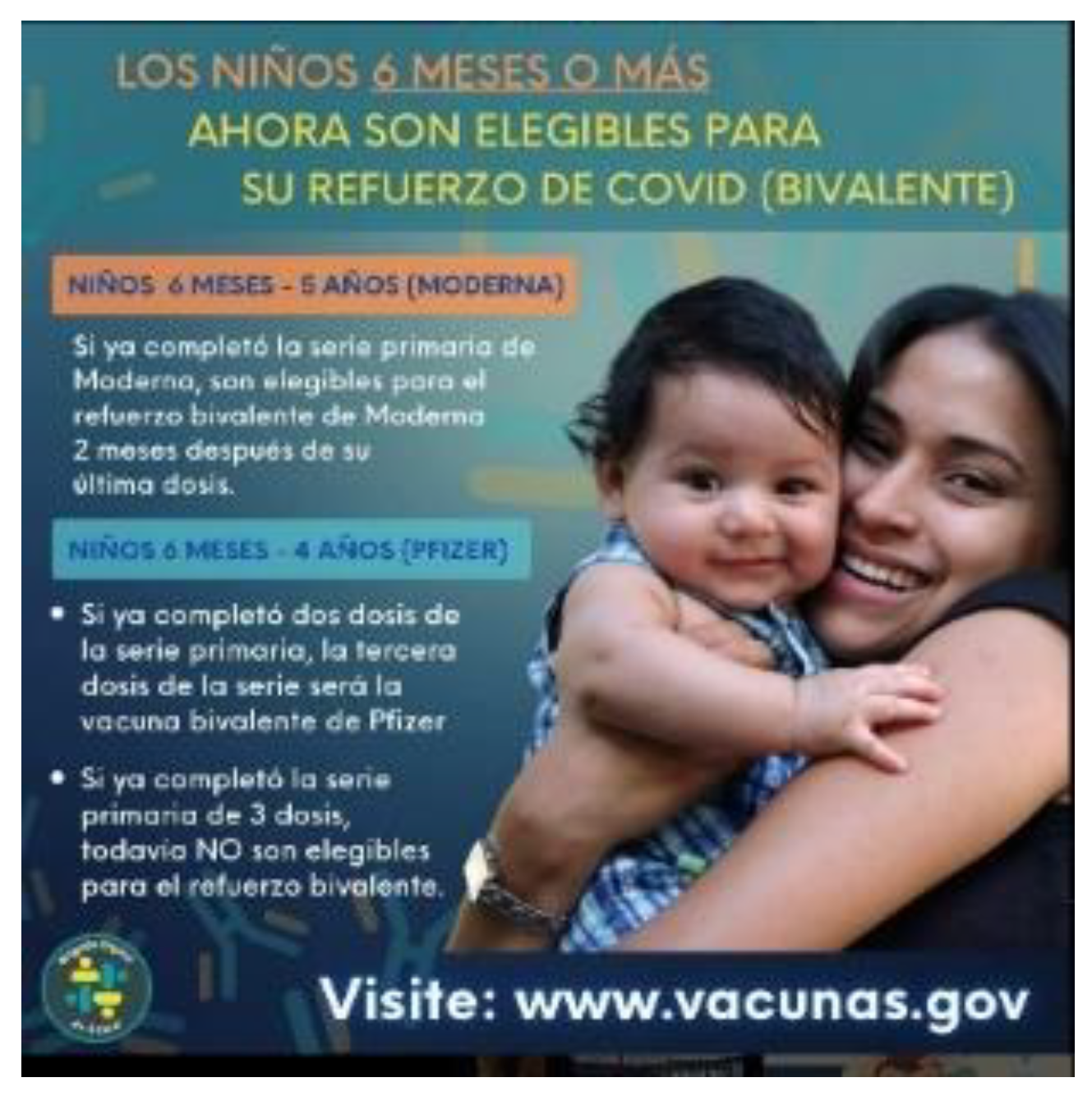

| COVID Vaccination – Child/Adolescent | 30 | 10 | 40 (10.92%) |

| COVID Vaccination – General | 81 | 11 | 92 (25.14%) |

| COVID Vaccination – Safety/Efficacy | 14 | 13 | 27 (7.38%) |

| Total = 251 | Total = 115 | Total = 366 |

| Post Purpose | Posts with Primary Purpose (N) |

Posts with Secondary Purpose (N) |

Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Address Misinformation | 5 | 29 | 34 (9.04%) |

| Educational/Health Promotion | 175 | 6 | 181 (48.14%) |

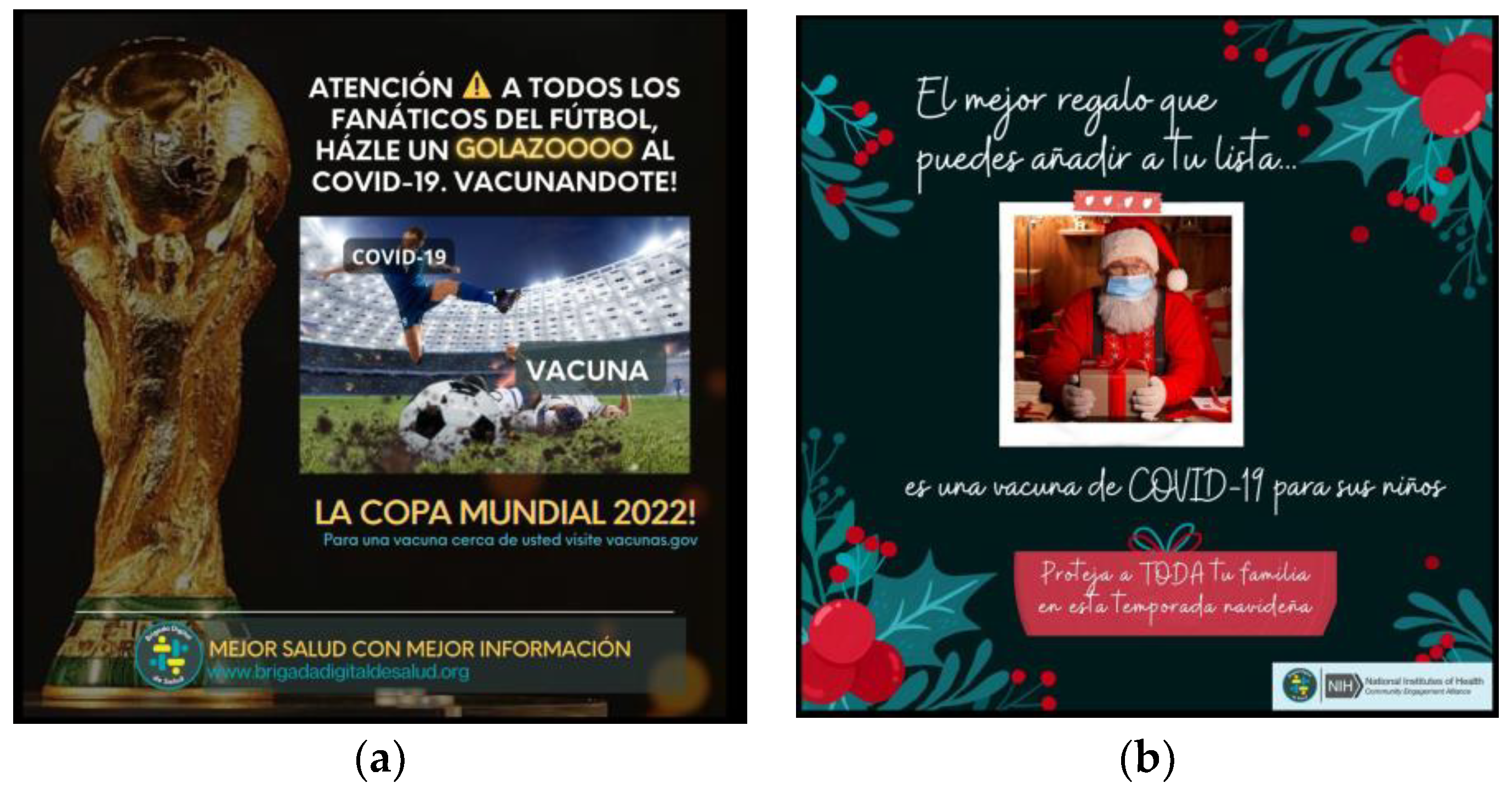

| Engagement/Entertainment | 33 | 20 | 53 (14.10%) |

| Popular Culture/Current Events | 14 | 22 | 36 (9.57%) |

| Link to Resource/Service/Event | 11 | 37 | 48 (12.76%) |

| News Update | 13 | 11 | 24 (6.38%) |

| Total = 251 | Total = 125 | Total = 376 |

| Post Format | Total N (%) |

|---|---|

| Carousel | 62 (24.70%) |

| Carousel – Music | 3 (1.20%) |

| Carousel – Narration | 4 (1.60%) |

| Image & Text | 127 (50.60%) |

| Image & Text – Animation | 6 (2.40%) |

| Image & Text – Music | 6 (2.40%) |

| Video | 38 (15.14%) |

| Video – Music | 5 (2.00%) |

| Total = 251 |

| Platform | Facebook (N=394) |

Instagram (N=419) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Women (%) | Men (%) | Women (%) | Men (%) |

| 18-24 | 3.6 | 2 | 5.7 | 1.8 |

| 25-34 | 15.7 | 3.8 | 27.1 | 8.1 |

| 35-44 | 27 | 6.3 | 27.8 | 8.4 |

| 45-54 | 19.1 | 4.6 | 12.7 | 1.5 |

| 55-64 | 9.1 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 0.9 |

| 65+ | 3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Total (%) | 77.5 | 22.5 | 79 | 21 |

| Metrics | Twitter (N=493 tweets) |

Facebook (N=275 posts) |

Instagram (N=254 posts) |

Total (N=1,022 posts) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reach | -- | 336,427 | 50,483 | 386,910 |

| Impressions | 37,809 | 431,018 | 83,210 | 552,037 |

| Post Engagements | 3,287 | 77,965 | 15,616 | 96,868 |

| Likes | 825 | 7,969 | 2,498 | 11,292 |

| Comments/Replies | 242 | 14,879* | 119 | 15,240 |

| Shares/Retweets | 411 | 7,833* | 1,474 | 9,718 |

| Video thru plays | -- | 40,251* | 5,130* | 45,381 |

| Detail Expands | 590 | -- | -- | 590 |

| Page/Profile Visits | 134 | 5,593 | 3,827 | 9,554 |

| Link Clicks | 51 | 460 | 230* | 741 |

| Post Topic | Format | Reach | Impressions | Engagement | Thru Plays | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Many vaccines require multiple doses, like routine child vaccines | Narrated video | 6,243 | 7,165 | 2,205 | 949 | Addressed misinformation, audio-narrated |

| Recap: 2 years since first COVID vaccine administered | Video with text & music | 4,684 | 2,815 | 1,595 | 1,209 | Music, typewriter text, visual appeal |

| Radio host interview with pediatrician - 1 | Video expert interview | 2,892 | 6,721 | 1,565 | 273 | Behind scenes of radio show with Latino celebrity Dr. host; credible expert |

| Radio host interview with pediatrician - 2 | Video expert interview | 1,666 | 3,608 | 1,108 | 220 | Behind scenes of radio show with Latino celebrity Dr. host; credible expert |

| Six things to know about COVID vaccine safety for children | Narrated Video | 2,124 | 2,319 | 1,104 | 968 | Addressed misinformation, audio-narrated; timed with start of school year |

| When to get booster dose | Narrated video tutorial CDC tool; link to website | 1,737 | 1,902 | 925 | 670 | Step-by-step, narrated instructional video on how to use online CDC resource in Spanish |

| Did you remember Mother’s Day? | Video dramatiza-tion | 22,173 | 25,738 | 6,943 | 3,125 | Social media influencer portrayed; repurposed humorous video with COVID messaging; trending topic – holiday |

| How to get free COVID-19 tests | Video - animated gif; link to website | 7,861 | 10,461 | 4,898 | 1,553 | Portrayed well-known Latino comedic actor with engaging expression; promoted free resource |

| Booster dose provides best protection | Image with music; link to website Engage- ment |

7,953 | 4,633 | 2,805 | 1,496 | Popular Latina music artist; trending topic - gossip of romantic breakup; upbeat dance music |

| How to order free COVID tests and masks | Video with music; link to website Engage- ment |

3,099 | 3,445 | 1,497 | 1,274 | Popular Latino music artist; music |

| Real life story of boosters reducing COVID transmission | Animated text with music Engage- ment |

4,173 | 4,470 | 1,294 | 972 | Storytelling; typewriter text; music; rhyming poem |

| Inflation prices are high, but COVID vaccines are still free | Video with text & music Engage- ment |

1,597 | 1,856 | 826 | 736 | Current events - price increases for popular items juxtaposed against free vaccine; upbeat music from popular artist |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).