Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

12 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

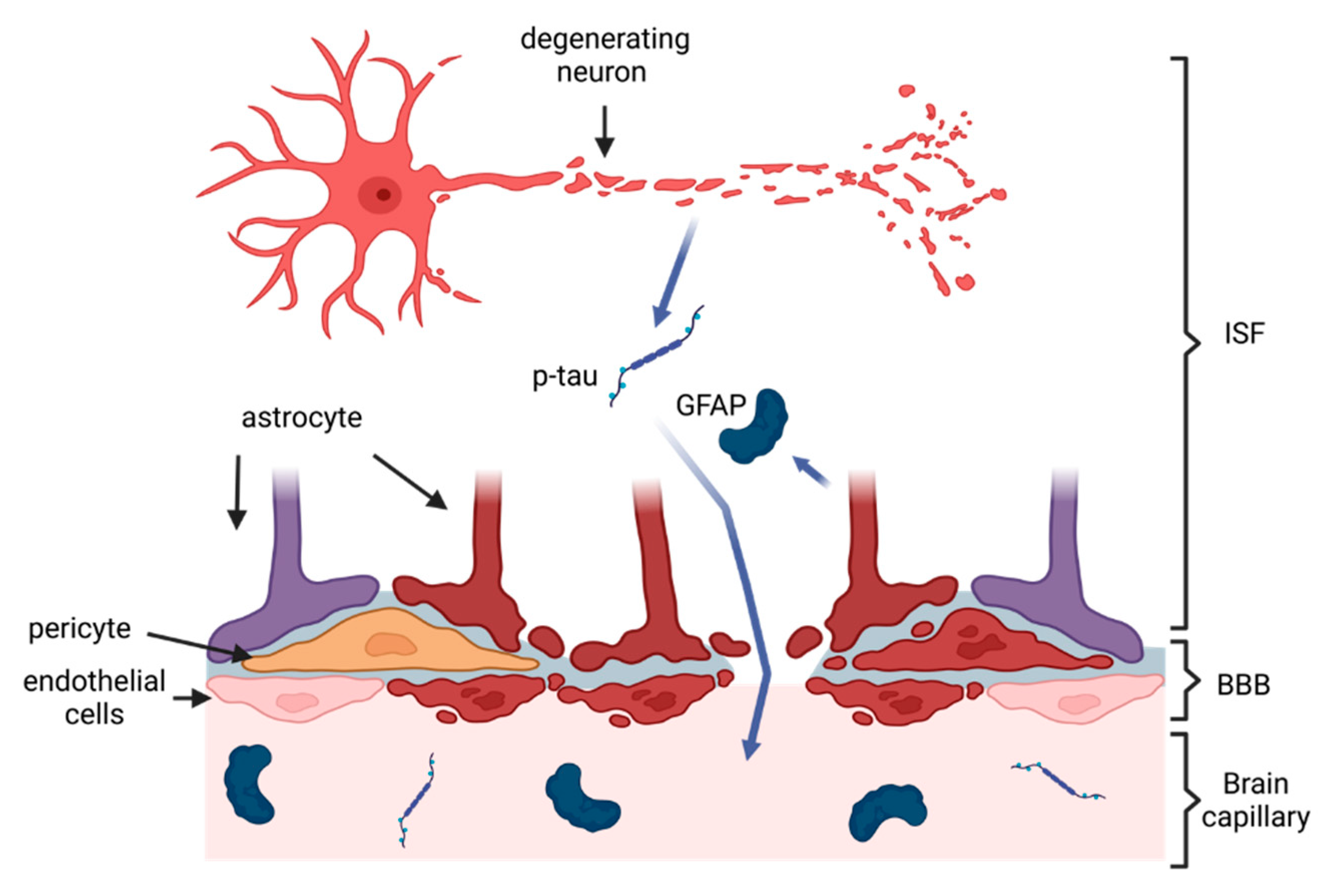

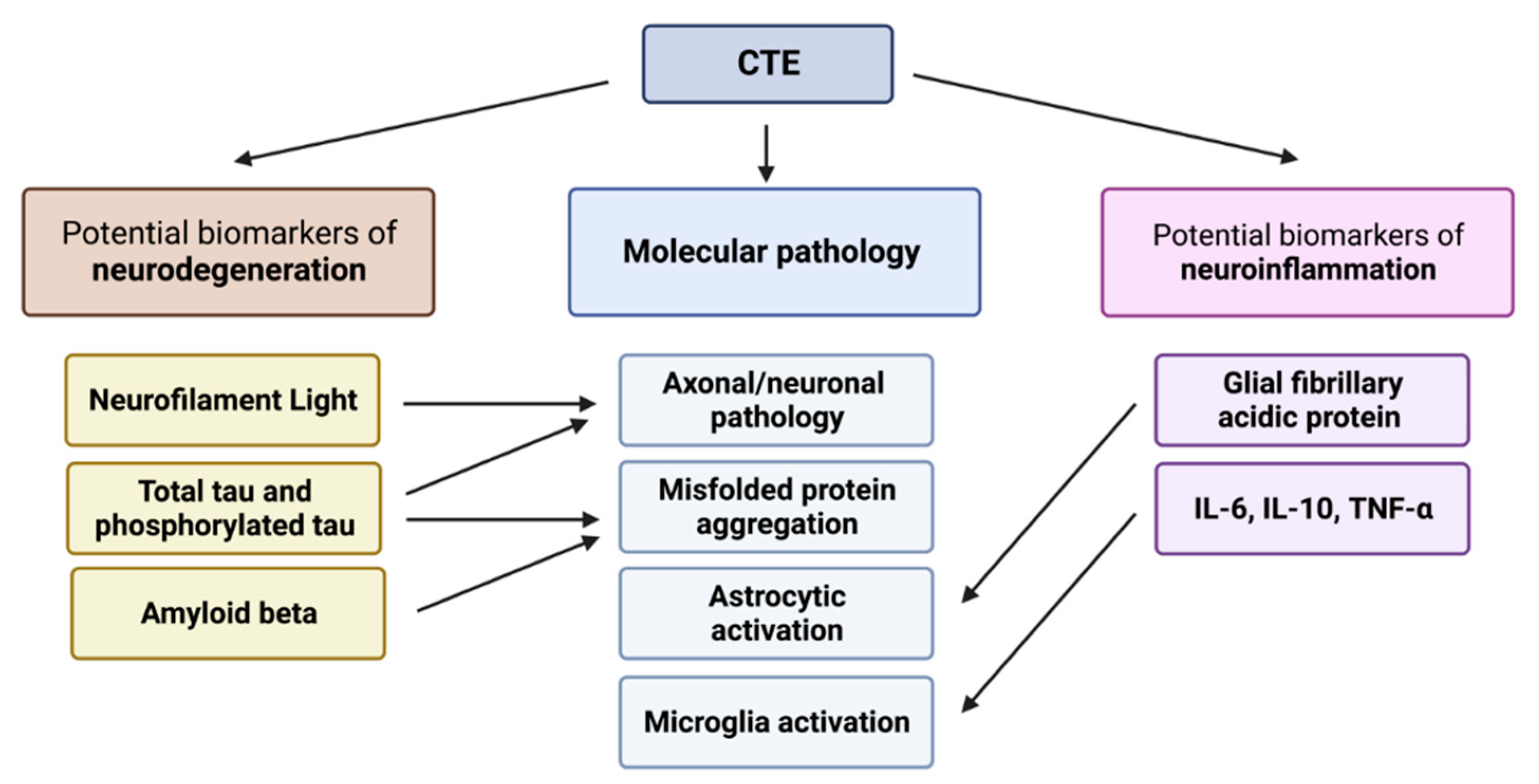

2. Pathology of CTE and Rationale for Blood-Based Biomarkers

3. Biomarkers of Neurodegeneration in CTE

3.1. Total Tau and Phosphorylated Tau

3.2. Amyloid Beta

3.3. Neurofilament Light

3.4. Other Biomarkers of Neurodegeneration

4. Biomarkers of Neuroinflammation in CTE

4.1. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

4.2. Inflammatory Cytokines

5. Micro RNA Biomarkers in CTE

6. Discussion and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global status report on the public health response to dementia. WHO 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis, Z; Shah, R. C.; Bennett, D.A. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA 2019, 322, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Tang, E.; Taylor, J.-P. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ 2015, 350, h3029–h3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martland, H.S. Punch Drunk. JAMA 1928, 91, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, N.; Wennberg, R.; Grenier, K.; Tartaglia, C.; Tator, C.; Hazrati, L.-N. Association of Position Played and Career Duration and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy at Autopsy in Elite Football and Hockey Players. Neurology 2021, 96, e1835–e1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omalu, B.I.; DeKosky, S.T.; Minster, R.L.; Kamboh, M.I.; Hamilton, R.L.; Wecht, C.H. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omalu, B.I.; DeKosky, S.T.; Hamilton, R.L.; Minster, R.L.; Kamboh, M.I.; Shakir, A.M.; Wecht, C.H. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player: Part II. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Stein, T.D.; Nowinski, C.J.; Stern, R.A.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Alvarez, V.E.; Lee, H.-S.; Hall, G.; Wojtowicz, S.M.; Baugh, C.M.; et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 2013, 136, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, T.D.; Montenigro, P.H.; Alvarez, V.E.; Xia, W.; Crary, J.F.; Tripodis, Y.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Mez, J.; Solomon, T.; Meng, G.; et al. Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mez, J.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Kiernan, P.T.; Abdolmohammadi, B.; Alvarez, V.E.; Huber, B.R.; Alosco, M.L.; Solomon, T.M.; Nowinski, C.J.; McHale, L.; et al. Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA 2017, 318, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, L.E.; Fisher, A.M.; Tagge, C.A.; Zhang, X.-L.; Velisek, L.; Sullivan, J.A.; Upreti, C.; Kracht, J.M.; Ericsson, M.; Wojnarowicz, M.W.; et al. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Blast-Exposed Military Veterans and a Blast Neurotrauma Mouse Model. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroon, J.C.; Winkelman, R.; Bost, J.; Amos, A.; Mathyssek, C.; Miele, V. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Contact Sports: A Systematic Review of All Reported Pathological Cases. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Stein, T.D.; Huber, B.R.; Crary, J.F.; Bieniek, K.; Dickson, D.; Alvarez, V.E.; Cherry, J.D.; Farrell, K.; Butler, M.; et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): criteria for neuropathological diagnosis and relationship to repetitive head impacts. Acta Neuropathol. 2023, OnlineFirst, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, R.A.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Baugh, C.M.; Seichepine, D.R.; Montenigro, P.H.; Riley, D.O.; Fritts, N.G.; Stamm, J.M.; Robbins, C.A.; McHale, L.; et al. Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology 2013, 81, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Yaffe, K. Epidemiology of mild traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative disease. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 66, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskiewicz, K.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Bailes, J.; McCrea, M.; Cantu, R.C.; Randolph, C.; Jordan, B.D. Association between Recurrent Concussion and Late-Life Cognitive Impairment in Retired Professional Football Players. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.C.; Sturm, V.E.; Peterson, M.J.; Pieper, C.F.; Bullock, T.; Boeve, B.F.; Miller, B.L.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Berger, M.S.; Kramer, J.H.; et al. Association of traumatic brain injury with subsequent neurological and psychiatric disease: a meta-analysis. JNS 2016, 124, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.E.; Byers, A.L.; Gardner, R.C.; Seal, K.H.; Boscardin, W.J.; Yaffe, K. Association of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury With and Without Loss of Consciousness With Dementia in US Military Veterans. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, K.; Konerth, N.; Entwistle, I.; Hume, P.; Theadom, A.; Lewis, G.; King, D.; Goodbourn, T.; Bottiglieri, M.; Ferraces-Riegas, P.; et al. Mental Health and Wellbeing of Retired Elite and Amateur Rugby Players and Non-contact Athletes and Associations with Sports-Related Concussion: The UK Rugby Health Project. Sports. Med. 2022, 52, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosco, M.L.; Culhane, J.; Mez, J. Neuroimaging Biomarkers of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Targets for the Academic Memory Disorders Clinic. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosco, M.L.; Tripodis, Y.; Fritts, N.G.; Heslegrave, A.; Baugh, C.M.; Conneely, S.; Mariani, M.; Martin, B.M.; Frank, S.; Mez, J.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau, Aβ, and sTREM2 in Former National Football League Players: Modeling the relationship between repetitive head impacts, microglial activation, and neurodegeneration. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, K.W.; Geada, A.; Alvarez, V.E.; Xia, W.; Cherry, J.D.; Nicks, R.; Meng, G.; Daley, S.; Tripodis, Y.; Huber, B.R. A comparison between tau and amyloid-β cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer disease. Alz. Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teunissen, C.E.; Verberk, I.M.W.; Thijssen, E.H.; Vermunt, L.; Hansson, O.; Zetterberg, H.; van der Flier, W.M.; Mielke, M.M.; del Campo, M. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: towards clinical implementation. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierre, M.U.; Telles, J.P.M.; Welling, L.C.; Rabelo, N.N.; Teixeira, M.J.; Figueiredo, E.G. Biomarkers for traumatic brain injury: a short review. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 2091–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamerlan, A.; Dominguez, J.; Ligsay, A.; Youn, Y.C.; An, S.S.A.; Kim, S. Current fluid biomarkers, animal models, and imaging tools for diagnosing chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Mol. Cel. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiskens, M.I.; Schneiders, A.G.; Angoa-Pérez, M.; Vella, R.K.; Fenning, A.S. Blood biomarkers for assessment of mild traumatic brain injury and chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Biomarkers 2020, 25, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahim, P.; Gill, J.M.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H. Fluid Biomarkers for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Semin. Neurol. 2020, 40, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergauer, A.; van Osch, R.; van Elferen, S.; Gyllvik, S.; Venkatesh, H.; Schreiber, R. The diagnostic potential of fluid and imaging biomarkers in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroudis, I.; Kazis, D.; Chowdhury, R.; Petridis, F.; Costa, V.; Balmus, I.-M.; Ciobica, A.; Luca, A.-C.; Radu, I.; Dobrin, R.P.; Baloyannis, S. Post-Concussion Syndrome and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Narrative Review on the Neuropathology, Neuroimaging and Fluid Biomarkers. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 740–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, K.; Molina, V.; Shukla, S.; Avila, A.; Fong, N.; Nguyen, J.; Lucke-Wold, B. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Diagnostic updates and advances. AIMSN 2022, 9, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckee, A.C.; Daneshvar, D.H. The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 127, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, G.; Zhao, J.; Dash, P.K.; Soto, C.; Moreno-Gonzalez, I. Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Tau Aggregation and Spreading. J. Neurotrauma 2020, 37, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.L.M.D.; Dixon, E.; Stein, T.D.; Alvarez, V.E.; Huber, B.; Buckland, M.E.; McKee, A.C.; Cherry, J.D. Tau Pathology in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy is Primarily Neuronal. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendron, T.F.; Petrucelli, L. The role of tau in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 2009, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, A.C.; Cantu, R.C.; Nowinski, C.J.; Hedley-Whyte, E.T.; Gavett, B.E.; Budson, A.E.; Santini, V.E.; Lee, H.-S.; Kubilus, C.A.; Stern, R.A. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: Progressive Tauopathy After Repetitive Head Injury. J Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2009, 68, 709–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Stein, T.D.; Kiernan, P.T.; Alvarez, V.E. The Neuropathology of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: CTE Neuropathology. Brain Pathol. 2015, 25, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.H.; Meaney, D.F.; Shull, W.H. Diffuse Axonal Injury in Head Trauma. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2003, 18, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglese, M.; Makani, S.; Johnson, G.; Cohen, B.A.; Silver, J.A.; Gonen, O.; Grossman, R.I. Diffuse axonal injury in mild traumatic brain injury: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J. Neurosurg. 2005, 103, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, A. Neurofilament phosphoforms: Surrogate markers for axonal injury, degeneration and loss. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 233, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedler, D.G.; Chuah, M.I.; Kirkcaldie, M.T.K.; Vickers, J.C.; King, A.E. Diffuse axonal injury in brain trauma: insights from alterations in neurofilaments. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.R.; Johnson, V.E.; Young, A.M.H.; Smith, D.H.; Stewart, W. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Is an Early Event That May Persist for Many Years After Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 74, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornguth, S.; Rutledge, N.; Perlaza, G.; Bray, J.; Hardin, A. A Proposed Mechanism for Development of CTE Following Concussive Events: Head Impact, Water Hammer Injury, Neurofilament Release, and Autoimmune Processes. Brain Sci. 2017, 7, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayeux, R. Biomarkers: Potential uses and limitations. Neurotherapeutics 2004, 1, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, P.; Manach, Y.L.; Riou, B.; Houle, T.T.; Warner, D.S. Statistical Evaluation of a Biomarker. Anesthesiology 2010, 112, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, J.E.; Begbie, F.D.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Smith, D.H.; Stewart, W. Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 2013, 136, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erturk, A.; Mentz, S.; Stout, E.E.; Hedehus, M.; Dominguez, S.L.; Neumaier, L.; Krammer, F.; Llovera, G.; Srinivasan, K.; Hansen, D.V. Interfering with the Chronic Immune Response Rescues Chronic Degeneration After Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 9962–9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C. The Neuropathology of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: The Status of the Literature. Semin. Neurol. 2020, 40, 359–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, H.C.; Osterman, C.; Bell, P.; Vinnell, L.; Curtis, M.A. Neuropathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a systematic review of comparative post-mortem histology literature. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, W.; Smith, D.H. Widespread Tau and Amyloid-Beta Pathology Many Years After a Single Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans: Long-Term AD-Like Pathology after Single TBI. Brain Pathol. 2012, 22, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosco, M.L.; Su, Y.; Stein, T.D.; Protas, H.; Cherry, J.D.; Adler, C.H.; Balcer, L.J.; Bernick, C.; Pulukuri, S.V.; Abdolmohammadi, B.; et al. Associations between near end-of-life flortaucipir PET and postmortem CTE-related tau neuropathology in six former American football players. Eur. J Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2022, 50, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.Z.; Cumming, P.; Nasrallah, F.A.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Escalation of Tau Accumulation after a Traumatic Brain Injury: Findings from Positron Emission Tomography. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgoraptis, N.; Li, L.M.; Whittington, A.; Zimmerman, K.A.; Maclean, L.M.; McLeod, C.; Ross, E.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H.; Passchier, J.; et al. In vivo detection of cerebral tau pathology in long-term survivors of traumatic brain injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraoka, S.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Tatebe, H.; DeLeo, A.M.; Ikezu, S.; Tokuda, T.; Gygi, S.P.; Stern, R.A.; Ikezu, T. Proteomic Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Isolated From Cerebrospinal Fluid of Former National Football League Players at Risk for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, R.; Sharma, D.R.; Chang, B.; Oumata, N.; Cam, M.; Vaucelle, L.; Lindberg, M.F.; Chiu, A.; Wisniewski, T.; Wang, K.K.W.; et al. Novel Mouse Tauopathy Model for Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Evaluation of Long-Term Effects on Cognition and Biomarker Levels After Therapeutic Inhibition of Tau Phosphorylation. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alosco, M.L.; Tripodis, Y.; Jarnagin, J.; Baugh, C.M.; Martin, B.; Chaisson, C.E.; Estochen, N.; Song, L.; Cantu, R.C.; Jeromin, A.; et al. Repetitive head impact exposure and later-life plasma total tau in former National Football League players. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2017, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, O.J.; Turner, M.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H. Fluid biomarkers and risk of neurodegenerative disease in retired athletes with multiple concussions: results from the International Concussion and Head Injury Research Foundation Brain health in Retired athletes Study of Ageing and Impact-Related Neurodegenerative Disease (ICHIRF-BRAIN study). BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2022, 8, e001327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahim, P.; Politis, A.; van der Merwe, A.; Moore, B.; Ekanayake, V.; Lippa, S.M.; Chou, Y.-Y.; Pham, D.L.; Butman, J.A.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; et al. Time course and diagnostic utility of NfL, tau, GFAP, and UCH-L1 in subacute and chronic TBI. Neurology 2020, 95, e623–e636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahim, P.; Zetterberg, H.; Simrén, J.; Ashton, N.J.; Norato, G.; Schöll, M.; Tegner, Y.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Blennow, K. Association of Plasma Biomarker Levels With Their CSF Concentration and the Number and Severity of Concussions in Professional Athletes. Neurology 2022, 99, e347–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilevskaya, A.; Taghdiri, F.; Multani, N.; Ozzoude, M.; Tarazi, A.; Khodadadi, M.; Wennberg, R.; Rusjan, P.; Houle, S.; Green, R.; et al. Investigating the use of plasma pTau181 in retired contact sports athletes. J Neurol. 2022, 269, 5582–5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, A.; Lejbman, N.; Jeromin, A.; French, L.M.; Kim, H.-S.; Cashion, A.; Mysliwiec, V.; Diaz-Arrasti, R.; Gill, J. Peripheral Total Tau in Military Personnel Who Sustain Traumatic Brain Injuries During Deployment. JAMA Neurol 2015, 72, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetterberg, H.; Wilson, D.; Andreasson, U.; Minthon, L.; Blennow, K.; Randall, J.; Hansson, O. Plasma tau levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2013, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arastoo, M.; Lofthouse, R.; Penny, L.K.; Harrington, C.R.; Porter, A.; Wischik, C.M.; Palliyil, S. Current Progress and Future Directions for Tau-Based Fluid Biomarker Diagnostics in Alzheimer’s Disease. IJMS 2020, 21, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A. Cloning of a big tau microtubule-associated protein characteristic of the peripheral nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 1983–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaepen, K.; Goekint, M.; Heyman, E.M.; Meeusen, R. Neuroplasticity—Exercise-Induced Response of Peripheral Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies in Human Subjects. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 765–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverse, E.; Guo, T.; Zimmerman, K.; Foiani, M.S.; Velani, B.; Morrow, P.; Adejuwon, A.; Bamford, R.; Underwood, N.; George, J.; et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light chain, but not tau, are biomarkers of sports-related mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ortiz, F.; Turton, M.; Kac, P.R.; Smirnov, D.; Premi, E.; Ghidoni, R.; Benussi, L.; Cantoni, V.; Saraceno, C.; Rivolta, J. Brain-derived tau: a novel blood-based biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease-type neurodegeneration. Brain 2020, 146, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Mielke, M.M. An Update on Blood-Based Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease Using the SiMoA Platform. Neurol. Ther. 2019, 8, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, V.A.; Devoto, C.; Leete, J.; Sass, D.; Acott, J.D.; Mithani, S.; Gill, J.M. Extracellular Vesicle Proteins and MicroRNAs as Biomarkers for Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, R.A.; Tripodis, Y.; Baugh, C.M.; Fritts, N.G.; Martin, B.M.; Chaisson, C.; Cantu, R.C.; Joyce, J.A.; Shah, S.; Ikezu, T. Preliminary Study of Plasma Exosomal Tau as a Potential Biomarker for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. JAD 2016, 51, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.; Mustapic, M.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Lange, R.; Gulyani, S.; Diehl, T.; Motamedi, V.; Osier, N.; Stern, R.A.; Kapogiannis, D. Higher exosomal tau, amyloid-beta 42 and IL-10 are associated with mild TBIs and chronic symptoms in military personnel. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, K.; Qu, B.-X.; Lai, C.; Devoto, C.; Motamedi, V.; Walker, W.C.; Levin, H.S.; Nolen, T.; Wilde, E.A.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; et al. Higher exosomal phosphorylated tau and total tau among veterans with combat-related repetitive chronic mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Elahi, F.M.; Mustapic, M.; Kapogiannis, D.; Pryhoda, M.; Gilmore, A.; Gorgens, K.A.; Davidson, B.; Granholm, A.; Ledreux, A. Altered levels of plasma neuron-derived exosomes and their cargo proteins characterize acute and chronic mild traumatic brain injury. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 5082–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraoka, S.; DeLeo, A.M.; Yang, Z.; Tatebe, H.; Yukawa-Takamatsu, K.; Ikezu, S.; Tokuda, T.; Issadore, D.; Stern, R.A.; Ikezu, T. Proteomic Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Separated from Plasma of Former National Football League Players at Risk for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltz, C.B.; Kenney, K.; Gill, J.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Gardner, R.C.; Yaffe, K. Blood biomarkers of traumatic brain injury and cognitive impairment in older veterans. Neurology 2020, 95, e1126–e1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Ji, X.; Lv, R.; Pei, J.-J.; Du, Y.; Shen, C.; Hou, X. Targetting Exosomes as a New Biomarker and Therapeutic Approach for Alzheimer’s Disease. CIA 2020, 15, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asken, B.M.; Tanner, J.A.; VandeVrede, L.; Mantyh, W.G.; Casaletto, K.B.; Staffaroni, A.M.; La Joie, R.; Iaccarino, L.; Soleimani-Meigooni, D.; Rojas, J.C. Plasma P-tau181 and P-tau217 in Patients With Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome With and Without Evidence of Alzheimer Disease Pathology. Neurology 2022, 99, e594–e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varesi, A.; Carrara, A.; Pires, V.G.; Floris, V.; Pierella, E.; Savioli, G.; Prasad, S.; Esposito, C.; Ricevuti, G.; Chirumbolo, S.; et al. Blood-Based Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis and Progression: An Overview. Cells 2022, 11, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, R.; Chang, B.; Yue, J.K.; Chiu, A.; Winkler, E.A.; Puccio, A.M.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Yuh, E.L.; Mukherjee, P.; Valadka, A.B.; et al. Comparing Plasma Phospho Tau, Total Tau, and Phospho Tau–Total Tau Ratio as Acute and Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury Biomarkers. JAMA Neurol 2017, 74, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathas, S.; Alvarez, V.E.; Xia, W.; Nicks, R.; Meng, G.; Daley, S.; Pothast, M.; Shah, A.; Kelley, H.; Esnault, C.; et al. Tau phosphorylation sites serine202 and serine396 are differently altered in chronic traumatic encephalopathy and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 1511–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Peltz, C.B.; Mustapic, M.; Kapogiannis, D.; Yaffe, K. Neuron-Derived Plasma Exosome Proteins after Remote Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2020, 37, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C-X. ; Liu, F.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Post-translational modifications of tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural. Transm. 2005, 112, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.H.; Chen, X.H.; Iwata, A.; Graham, D.I. Amyloid beta accumulation in axons after traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurosurg. 2003, 98, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, A.; Csajbok, L.; Ost, M.; Höglund, K.; Nylén, K.; Rosengren, L.; Nellgård, B.; Blennow, K. Marked increase of beta-amyloid(1-42) and amyloid precursor protein in ventricular cerebrospinal fluid after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurol. 2004, 251, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Goyal, R. Amyloid beta plaque: a culprit for neurodegeneration. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2016, 116, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lejbman, N.; Olivera, A.; Heinzelmann, M.; Feng, R.; Yun, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Gill, J. Active duty service members who sustain a traumatic brain injury have chronically elevated peripheral concentrations of A β 40 and lower ratios of A β 42/40. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Teunissen, C.E.; Otto, M.; Piehl, F.; Sormani, M.P.; Gattringer, T.; Barro, C.; Kappos, L.; Comabella, M.; Fazekas, F.; et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2008, 14, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Nimer, F.; Thelin, E.; Nyström, H.; Dring, A.M.; Svenningsson, A.; Piehl, F.; Nelson, D.W.; Bellander, B.M. Comparative Assessment of the Prognostic Value of Biomarkers in Traumatic Brain Injury Reveals an Independent Role for Serum Levels of Neurofilament Light. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0132177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahim, P.; Gren, M.; Liman, V.; Andreasson, U.; Norgren, N.; Tegner, Y.; Mattsson, N.; Andreasen, N.; Ost, M.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Serum neurofilament light protein predicts clinical outcome in traumatic brain injury. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutté, A.M.; Thangavelu, B.; LaValle, C.R.; Nemes, J.; Gilsdorf, J.; Shear, D.A.; Kamimori, G.H. Brain-related proteins as serum biomarkers of acute, subconcussive blast overpressure exposure: A cohort study of military personnel. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, X.; Wu, Q.; Yan, J.; Mao, G.; Xing, W. Neurofilament light chain level in traumatic brain injury: A system review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e22363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickstein, D.L.; De Gasperi, R.; Gama Sosa, M.A.; Perez-Garcia, G.; Short, J.A.; Sosa, H.; Perez, G.M.; Tschiffely, A.E.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Pullman, M.Y.; et al. Brain and blood biomarkers of tauopathy and neuronal injury in humans and rats with neurobehavioral syndromes following blast exposure. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5940–5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, S.; Leete, J.; Shahim, P.; Pattinson, C.; Guedes, V.A.; Lai, C.; Devoto, C.; Qu, B.-X.; Greer, K.; Moore, B. Extracellular vesicle concentrations of glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light measured 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asken, B.M.; Tanner, J.A.; Vande-Vrede, L.; Casaletto, K.B.; Staffaroni, A.M.; Mundada, N.; Fonseca, C.; Iaccarino, L.; La Joie, R.; Tsuei, T.; et al. Multi-Modal Biomarkers of Repetitive Head Impacts and Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome: A Clinicopathological Case Series. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, P.; Rocca, D.; Henley, J.M. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1): structure, distribution and roles in brain function and dysfunction. The Biochemical journal 2016, 473, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhrfelt, A.; Johansson, P.; Wallin, A.; Andreasson, U.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Svensson, J. Increased Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of Ubiquitin Carboxyl-Terminal Hydrolase L1 in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra 2016, 6, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczynska-Przybik, A.; Dulewicz, M.; Mroczko, P.; Borawska, R.; Doroszkiewicz, J.; Litman-Zawadzka, A.; Arslan, D.; Slowik, A. The assessment of ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-1 (UCH-L1) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, e062156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.W.; Alvarez, V.E.; Mez, J.; Huber, B.R.; Tripodis, Y.; Xia, W.; Meng, G.; Kubilus, C.A.; Cormier, K.; Kiernan, P.T.; et al. Lewy Body Pathology and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Associated With Contact Sports. J Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 77, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, R.M.; Fairlie, D.P.; Mason, J.M. Alpha-synuclein structure and Parkinson’s disease—lessons and emerging principles. Mol Neurodegeneration 2019, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, D.; Gonzales-Portillo, G.S.; Acosta, S.; de la Pena, I.; Tajiri, N.; Kaneko, Y.; Borlongan, C.V. Neuroinflammatory responses to traumatic brain injury: etiology, clinical consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loane, D.J.; Kumar, A. Microglia in the TBI brain: The good, the bad, and the dysregulated. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesnila, N. The immune system in traumatic brain injury. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 26, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Praino, L.E.; Corrigan, F. Does neuroinflammation drive the relationship between tau hyperphosphorylation and dementia development following traumatic brain injury? Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 60, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odfalk, K.F.; Bieniek, K.F.; Hopp, S.C. Microglia: Friend and foe in tauopathy. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 216, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, J.M.; Wang, Y.; Munro, C.A.; Ma, S.; Yue, C.; Chen, S.; Airan, R.; Kim, P.K.; Adams, A.V.; Garcia, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and brain atrophy in former NFL players: An in vivo multimodal imaging pilot study. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 74, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loane, D.J.; Kumar, A.; Stoica, B.A.; Cabatbat, R.; Faden, A.I. Progressive neurodegeneration after experimental brain trauma: association with chronic microglial activation. J Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofroniew, M.V.; Vinters, H.V. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta neuropathologica, 2010, 119, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burda, J.E.; Bernstein, A.M.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive astrocytes: production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhak, A.; Foschi, M.; Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Yue, J.K.; D’Anna, L.; Huss, A.; Oeckl, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Kuhle, J.; Petzold, A. Blood GFAP as an emerging biomarker in brain and spinal cord disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumpkins, K.M.; Bochicchio, G.V.; Keledjian, K.; Simard, J.M.; McCunn, M.; Scalea, T. Glial fibrillary acidic protein is highly correlated with brain injury. J Trauma. 2008, 65, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, J.; Latour, L.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Motamedi, V.; Turtzo, C.; Shahim, P.; Mondello, S.; DeVoto, C.; Veras, E.; Hanlon, D.; et al. Glial fibrillary acidic protein elevations relate to neuroimaging abnormalities after mild TBI. Neurology 2018, 91, e1385–e1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebschmann, N.A.; Luoto, T.M.; Karr, J.E.; Berghem, K.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Ashton, N.J.; Simrén, J.; Posti, J.P.; Gill, J.M.; et al. Comparing Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP) in Serum and Plasma Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Older Adults. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilad, S.; Meiri, E.; Yogev, Y.; Benjamin, S.; Lebanony, D.; Yerushalmi, N.; Benjamin, H.; Kushnir, M.; Cholakh, H.; Melamed, N.; Bentwich, Z.; Hod, M.; Goren, Y.; Chajut, A. Serum MicroRNAs Are Promising Novel Biomarkers. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiskens, M.I.; Mengistu, T.S.; Li, K.M.; Fenning, A.S. Systematic Review of the Diagnostic and Clinical Utility of Salivary microRNAs in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). IJMS 2022, 23, 13160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhomia, M.; Balakathiresan, N.S.; Wang, K.K.; Papa, L.; Maheshwari, R.K. A Panel of Serum MiRNA Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Severe to Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redell, J.B.; Moore, A.N.; Ward, N.H.; Hergenroeder, G.W.; Dash, P.K. Human Traumatic Brain Injury Alters Plasma microRNA Levels. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyczechowska, D.; Harch, P.G.; Mullenix, S.; Fannin, E.S.; Chiappinelli, B.B.; Jeansonne, D.; Lassak, A.; Bazan, N.G.; Peruzzi, F. Serum microRNAs associated with concussion in football players. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1155479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvia, M.; Aytan, N.; Spencer, K.R.; Foster, Z.W.; Rauf, N.A.; Guilderson, L.; Robey, I.; Averill, J.G.; Walker, S.E.; Alvarez, V.E.; et al. MicroRNA Alterations in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 855096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, V.; Fallen, S.; Baxter, D.; Scherler, K.; Kim, T.-K.; Zhou, Y.; Meabon, J.S.; Logsdon, A.F.; Banks, W.A.; Schindler, A.G.; et al. Alterations in Plasma microRNA and Protein Levels in War Veterans with Chronic Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2020, 37, 1418–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Guo, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Qiang, J.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. Potential blood biomarkers for chronic traumatic encephalopathy: The multi-omics landscape of an observational cohort. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1052765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y; Huang, W; Constantini, S. The Differences between Blast-Induced and Sports-Related Brain Injuries. Front Neurol. 2013, 4, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patricios, J.S.; Schneider, K.J.; Dvorak, J.; Ahmed, O.H.; Blauwet, C.; Cantu, R.C.; Davis, G.A.; Echemendia, R.J.; Makdissi, M.; McNamee, M.; et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport–Amsterdam, October 2022. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, J.P.; Priemer, D.S.; Perl, D.P.; Filley, C.M. Sports Concussion and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Finding a Path Forward. Ann. Neurol. 2023, 93, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowinski, C.J.; Bureau, S.C.; Buckland, M.E.; Curtis, M.A.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Faull, R.L.M.; Grinberg, L.T.; Hill-Yardin, E.L.; Murray, H.C.; Pearce, A.J.; et al. Applying the Bradford Hill Criteria for Causation to Repetitive Head Impacts and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 938163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J; Li, P. ; Zhang, T.; Xu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, R.; Du, L. Review on Strategies and Technologies for Exosome Isolation and Purification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 9, 811971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sass, D.; Guedes, V.A.; Smith, E.G.; Vorn, R.; Devoto, C.; Edwards, K.A.; Mithani, S.; Hentig, J.; Lai, C.; Wagner, C. Sex Differences in Behavioral Symptoms and the Levels of Circulating GFAP, Tau, and NfL in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 746491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alosco, M.L.; Mariani, M.L.; Adler, C.H.; Balcer, L.J.; Bernick, C.; Au, R.; Banks, S.J.; Barr, W.B.; Bouix, S.; Cantu, R.C.; et al. Developing methods to detect and diagnose chronic traumatic encephalopathy during life: rationale, design, and methodology for the DIAGNOSE CTE Research Project. Alz. Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amerongen, S.; Caton, D.K.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Barkhof, F.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Teunissen, C.E.; Rozemuller, A.J.M.; Hoozemans, J.J.M.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Scheltens, P.; et al. Rationale and design of the “NEurodegeneration: Traumatic brain injury as Origin of the Neuropathology (NEwTON)” study: a prospective cohort study of individuals at risk for chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Alz. Res. Therapy 2022, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).