Submitted:

12 July 2023

Posted:

12 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Study Quality Assessment

3.3. Marital Status in Suicidal Behavior

3.4. Country-wise Variation

| SN | Study | Country | Place of study | Study duration (month) | Data collection year | Data Collection Methods | Study setting | Sources of cases | Suicidal behavior | Method | Number of cases | Male | Female | Age of respondents (Years) Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdullah et al., 2018 (23) | Pakistan | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 8 | 2015 | psychological autopsy interviews | urban | hospital | fatal | mixed | 63 | 38 | 25 | 22.10+3.08 |

| 2 | Acherjya et al., 2020 (24) | Bangladesh | Jashore | 6 | 2018 | interview | urban | hospital | fatal | poisoning | 474 | 223 | 251 | 27±11 |

| 3 | Ahmad et al., 2017 (25) | Pakistan | Karachi | 60 | 2011-2015 | record review and interviews | urban | police records and poison centre | both | mixed | 700 | 450 | 250 | 28.19± 8.79 in male, 26.07±8.25 years in female |

| 4 | Ali et al., 2022 (26) | Pakistan | Punjab | 48 | 2018-2021 | interview | Urban | Community | fatal | mixed | 100 | 60 | 40 | 26 |

| 5 | Ambade et al., 2007 (27) | India | Maharashtra | 36 | 1998-2000 | record review | urban | mortuary data and police records | fatal | mixed | 1127 | 704 | 423 | |

| 6 | Ambade et al., 2015 (28) | India | Maharashtra | 60 | 2001-2005 | record review | rural | police and autopsy records | fatal | hanging | 127 | 107 | 20 | 10-80 years |

| 7 | Arafat et al., 2020 (29) | Bangladesh | 12 | 2018-2019 | reviewing online news reports | both | community | both | mixed | 199 | 94 | 105 | 26.86±13.60 | |

| 8 | Arafat et al., 2020 (30) | Bangladesh | 12 | 2018-2019 | reviewing of print news reports | both | community | both | mixed | 403 | 179 | 224 | 25.81±11.62 | |

| 9 | Arafat et al., 2021 (31) | Bangladesh | Dhaka | 13 | 2019-2020 | interviews | urban | community | fatal | mixed | 100 | 49 | 51 | 26.30 ±12.36 |

| 10 | Arafat et al., 2018 (32) | Bangladesh | 120 | 2009-2018 | reviewing online news content | both | community | both | mixed | 358 | 142 | 215 | 23.84±11.42 | |

| 11 | Armstrong et al., 2019 (33) | India | Tamil nadu | 7 | 2016 | reviewing print news papers | both | Community | fatal | mixed | 988 | 467 | 521 | |

| 12 | Badiye et al., 2014 (34) | India | Maharastra | 60 | 2009-2013 | record review | urban | Records from crime branch | fatal | mixed | 2306 | 1647 | 659 | |

| 13 | Bansal et al., 2011 (35) | India | Punjab | 12 | 2010 | interview | urban | hospital | non-fatal | mixed | 100 | 61 | 39 | 26.98 ±8.13 |

| 14 | Bashir et al., 2014 (36) | Pakistan | Karachi | 6 | interview | urban | hospital | non-fatal | poisoning | 374 | 230 | 144 | 25 ±10.1 | |

| 15 | Bastia & Kar, 2009 (37) | India | Cuttack | 24 | 1998-1999 | interview and record review | urban | Community | fatal | hanging | 104 | 43 | 61 | 28.7 ±11.4 |

| 16 | Bhatia et al., 2006 (38) | India | Delhi | 60 | reviewing suicide notes and interviews | urban | Forensic data | fatal | mixed | 40 | 26 | 14 | ||

| 17 | Bhatia et al., 2000 (39) | India | Delhi | record review, interviews | urban | hospital | Both | mixed | 373 | 189 | 184 | |||

| 18 | Bhise and Behere, 2016 (40) | India | Maharashtra | 18 | 2008-2009 | interview | rural | community people | fatal | mixed | 98 | 88 | 10 | |

| 19 | Chandrasekaran & Gnanaselane, 2005 (41) | India | Puducherry | 12 | 2001-2002 | interview | mixed | hospital | non-fatal | mixed | 341 | 153 | 188 | 26.1±9.3 |

| 20 | Chaudhari et al., 2022 (42) | India | Puducherry | 60 | 2010-2014 | record review | both | Forensic records | fatal | poisoning | 595 | 363 | 232 | 35.8 +14.6 |

| 21 | Fernando et al., 2010 (43) | Sri Lanka | Colombo | 12 | 2006 | interview | urban | court records | fatal | mixed | 151 | 93 | 58 | |

| 22 | Hagaman et al., 2017 (44) | Nepal | Nepal | 4 | 2015-2016 | interview and reviewing police records | both | community | fatal | mixed | 302 | 172 | 130 | 32.9+17.55 |

| 23 | Halder & Mahato, 2016 (45) | India | Kolkata | 24 | 2013-2014 | interview | urban | hospital | non-fatal | mixed | 100 | 28 | 72 | 23.51 ± 6.38 |

| 24 | Kar, 2010 (46) | India | Orissa | 24 | 1994-1996 | interview | urban | hospital | non-fatal | mixed | 149 | 65 | 84 | 31.6 ±13.5 years |

| 25 | Khan et al., 2005 (47) | India | Secunderabad | 1 | 2005 | interview | both | hospital | fatal | mixed | 50 | 29 | 21 | |

| 26 | Khan et al., 2008 (48) | Pakistan | Karachi | 12 | 2003 | interview, psychological autopsy method | urban | community people | fatal | mixed | 100 | 83 | 17 | |

| 27 | Khan et al., 2009 (49) | Pakistan | Ghizer | 48 | 2000-2004 | Police records and Interview | Urban | Police records | fatal | mixed | 49 | 49 | ||

| 28 | Kumar et al., 2015 (50) | India | Lucknow | 60 | 2008-2012 | record review | both | hospital | fatal | burning | 857 | 66 | 791 | 33.74 ± 11.64 |

| 29 | Kumar & Hashim, 2017 (51) | India | Karnataka | 36 | 2013 - 2015 | record review | rural | hospital | fatal | mixed | 426 | 355 | 71 | 34.7 |

| 30 | Kumar et al., 2011 (52) | India | Kerala | 6 | 2004 | Interview | rural | community | fatal | mixed | 166 | 124 | 42 | 40.45+17.07 |

| 31 | Manoranjitham et al., 2010 (53) | India | Tamil Nadu | 20 | 2006-2008 | psychological autopsy interview | rural | community | fatal | mixed | 100 | 59 | 41 | 42.24 ±20.69 |

| 32 | Mayer & Ziaian, 2002 (54) | India | 1995 | record review | both | community sample | fatal | mixed | 89178 | 52357 | 36821 | |||

| 33 | Mohanty et al., 2007 (55) | India | Berhampur | 48 | 2000-2003 | record review, interviews | both | hospital | fatal | mixed | 588 | 300 | 288 | |

| 34 | Naz, 2016 (56) | Pakistan | Punjab | 10 | 2014-2015 | reviewing newspaper content | both | community people | fatal | mixed | 87 | 50 | 37 | |

| 35 | Pal et al., 2022 (57) | India | Madhya Pradesh | 12 | 2020-2021 | interview | Urban | hospital | non fatal | mixed | 60 | 38 | 22 | 39.03±11.58 |

| 36 | Parkar et al., 2009 (58) | India | Mumbai | 84 | 1997-2003 | Interview | urban slums | community people | fatal | mixed | 76 | 33 | 43 | |

| 37 | Patel et al., 2012 (59) | India | 36 | 2001-2003 | Interview | both | community sample | fatal | mixed | 2684 | 1393 | 964 | ||

| 38 | Reza et al., 2013 (60) | Bangladesh | 24 | interview | rural | hospital | both | mixed | 113 | 44 | 69 | 29.6±12.8 | ||

| 39 | Sadia et al., 2021 (61) | Pakistan | Sargodha | 12 | 2019 | record review | both | hospital | both | wheatbill (aluminium phosphide) | 83 | 42 | 41 | |

| 40 | Sahoo et al., 2016 (62) | India | Jamshedpur | 6 | 2013–2014 | interview | both | hospital | non-fatal | mixed | 101 | 42 | 59 | |

| 41 | Saaiq & Ashraf, 2014 (63) | Pakistan | Islamabad | 24 | 2010 - 2012 | interviews and record review | both | hospital | both | burning | 93 | 18 | 75 | 26.89±6.1 |

| 42 | Samaraweera et al., 2008 (64) | Sri Lanka | Ratnapura | 3 | interviews, psychological autopsy | urban | community people | fatal | mixed | 27 | 19 | 8 | 43 | |

| 43 | Shah et al., 2017 (65) | Bangladesh | 6 | 2016-2017 | reviewing print news reports | both | community | fatal | mixed | 271 | 113 | 158 | 26.67 ± 13.47 | |

| 44 | Sharmin Salam et al., 2017 (66) | Bangladesh | 4 sub-districts | 6 | 2013 | interview | rural | Community | both | mixed | 95 | 48 | 47 | |

| 45 | Srivastava, 2013 (67) | India | Goa | 36 | 2005-2007 | record review and interviews | urban | community | fatal | mixed | 100 | 70 | 30 | |

| 46 | Vijayakumar & Rajkumar, 1999 (68) | India | Chennai | 14 | 1994-1995 | interviews, and record review | urban | community | fatal | mixed | 100 | 55 | 45 | |

| 47 | Vijayakumar et al., 2008 (69) | India | Chennai | 23 | 2002-2003 | Interview | urban | hospital | non fatal | 509 | 244 | 265 | 25.85±9.28 |

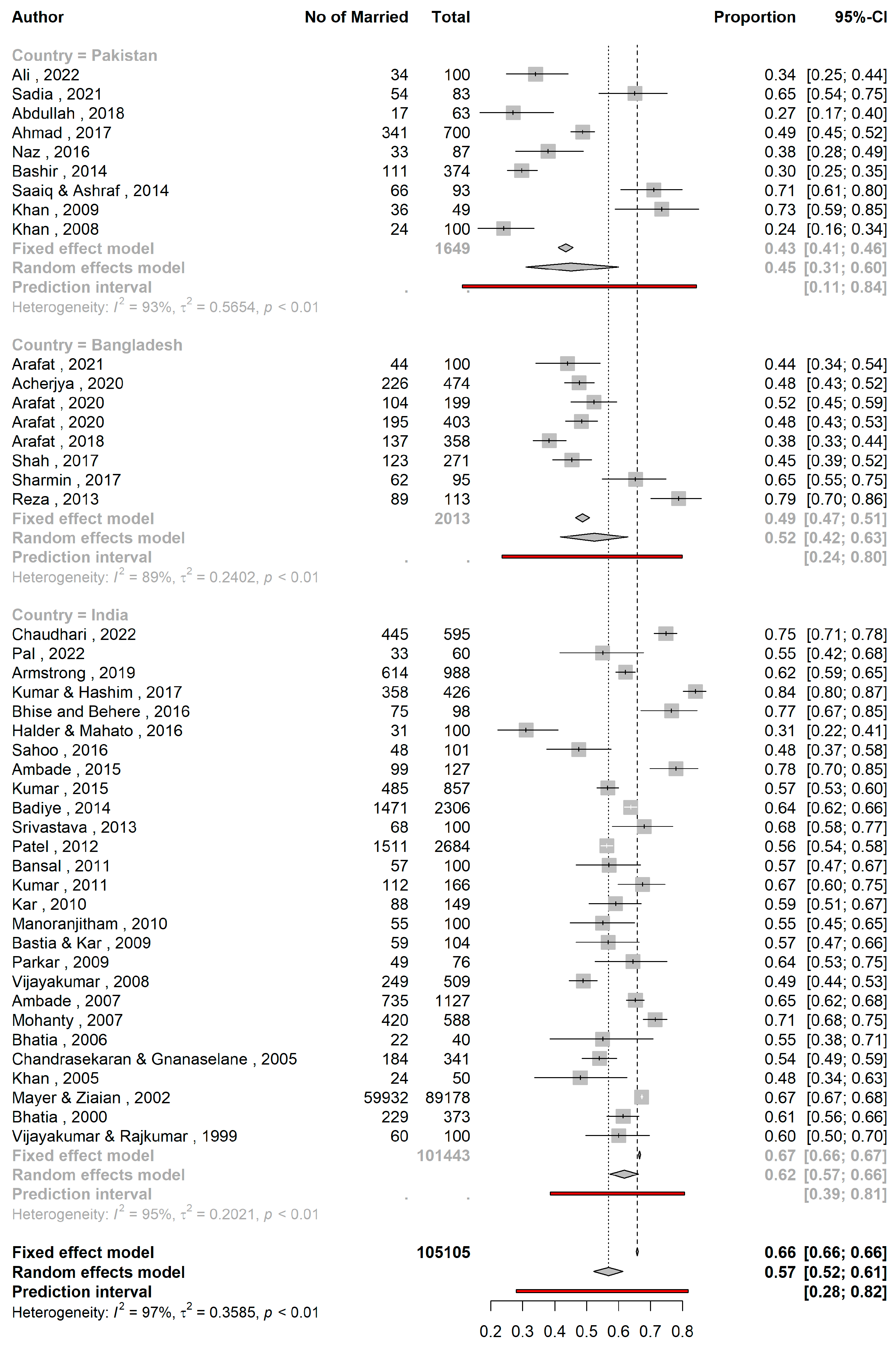

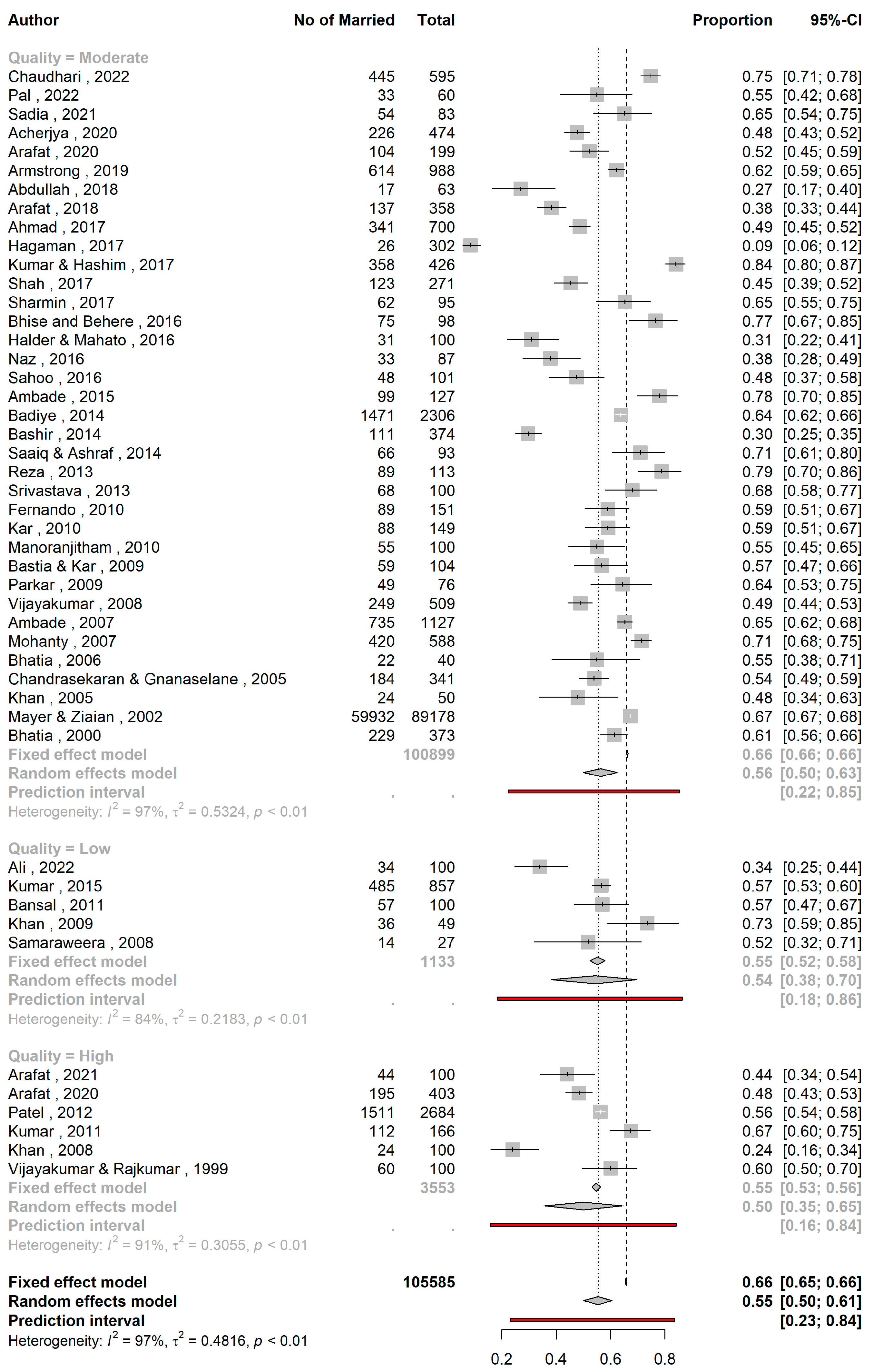

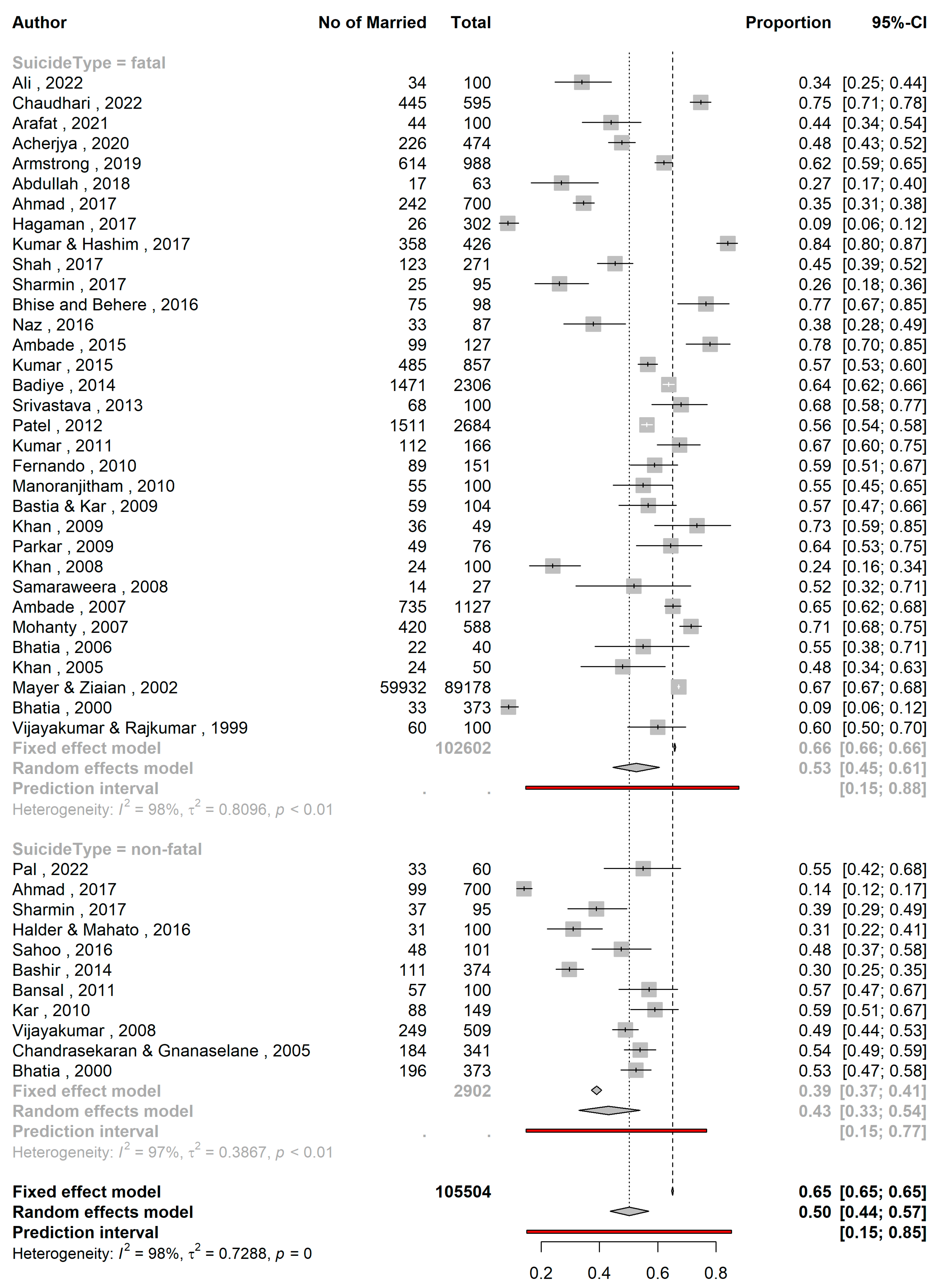

| Subgroups | Pooled proportions | 95%CI | I2 | Psubgroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatality | 0.13 | |||

| Fatal (k=33) | 0.53 | 0.45 – 0.61 | 97.8% | |

| Nonfatal (k=11) | 0.43 | 0.33 – 0.54 | 96.6% | |

| Country | 0.0155 | |||

| Pakistan (k=9) | 0.45 | 0.31 – 0.59 | 93.2% | |

| Bangladesh (k=8) | 0.52 | 0.42 – 0.63 | 89.0% | |

| India (k=27) | 0.62 | 0.57 – 0.66 | 94.6% | |

| Quality | 0.6328 | |||

| Low (k=5) | 0.54 | 0.38– 0.69 | 83.5% | |

| Moderate (k=36) | 0.56 | 0.38 – 0.69 | 96.9% | |

| High (k=6) | 0.51 | 0.35 – 0.65 | 91.4% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Major Findings of the Study

4.2. Implications of the Study Results

4.3. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Suicide Worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/131056 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Li, Z.; Page, A.; Martin, G.; Taylor, R. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, S. Suicide: A 15-year review of the sociological literature. Part II: Modernization and social integration perspectives. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2000, 30, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kyung-Sook, W.; SangSoo, S.; Sangjin, S.; Young-Jeon, S. Marital status integration and suicide: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 197, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuchi, N.; Kakizaki, M.; Sugawara, Y.; Tanji, F.; Watanabe, I.; Fukao, A.; Tsuji, I. Association of marital status with the incidence of suicide: A population-based Cohort Study in Japan (Miyagi cohort study). J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, A.; Hjelmeland, H.; Arensman, E.; De Leo, D. Social-Environmental Factors and Suicide Mortality: A Narrative Review of over 200 Articles. Sociol. Mind 2013, 03, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, P.S.; Yousuf, S.; Chan, C.H.; Yung, T.; Wu, K.C.-C. The roles of culture and gender in the relationship between divorce and suicide risk: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kposowa, A.J.; McElvain, J.P.; Breault, K.D. Immigration and Suicide: The Role of Marital Status, Duration of Residence, and Social Integration. Arch. Suicide Res. 2008, 12, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutright, P.; Fernquist, R.M. Effects of Societal Integration, Period, Region, and Culture of Suicide on Male Age-Specific Suicide Rates: 20 Developed Countries, 1955–1989. Soc. Sci. Res. 2000, 29, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, L.; Osváth, P.; Rihmer, Z.; Döme, P. Associations between marital and educational status and risk of completed suicide in Hungary. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 190, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Fujita, T.; Tachimori, H.; Takeshima, T.; Inagaki, M.; Sudo, A. Age-adjusted relative suicide risk by marital and employment status over the past 25 years in Japan. J. Public Health 2013, 35, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururaj, G.; Isaac, M.K.; Subbakrishna, D.K.; Ranjani, R. Risk factors for completed suicides: A case–control study from Bangalore, India. Inj. Control. Saf. Promot. 2004, 11, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Tu, X.-M.; Xiao, S.; Jia, C. Risk factors for rural young suicide in China: A case–control study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 129, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wieczorek, W.; Conwell, Y.; Tu, X.-M.; Wu, B.Y.-W.; Xiao, S.; Jia, C. Characteristics of young rural Chinese suicides: A psychological autopsy study. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, J.-Y.; Xirasagar, S.; Liu, T.-C.; Li, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-C. Does Marital Status Predict the Odds of Suicidal Death in Taiwan? A Seven-Year Population-Based Study. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2008, 38, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Saleem, T.; Menon, V.; Ali, S.A.; Baminiwatta, A.; Kar, S.K.; Akter, H.; Singh, R. Depression and suicidal behavior in South Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Ment. Health 2022, 9, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Ali, S.A.; Menon, V.; Hussain, F.; Ansari, D.S.; Baminiwatta, A.; Saleem, T.; Singh, R.; Varadharajan, N.; Biyyala, D.; et al. Suicide methods in South Asia over two decades (2001–2020). Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 920–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Menon, V.; Varadharajan, N.; Kar, S.K. Psychological Autopsy Studies of Suicide in South East Asia. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2022, 44, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G. ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2000. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Barker, T.H.; Migliavaca, C.B.; Stein, C.; Colpani, V.; Falavigna, M.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: A guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Khalily, M.T.; Ahmad, I.; Hallahan, B. Psychological autopsy review on mental health crises and suicide among youth inPakistan. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 2018, 10, e12338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acherjya, G.K.; Ali, M.; Alam, A.B.M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Mowla, S.G.M. The Scenario of Acute Poisoning in Jashore, Bangladesh. J. Toxicol. 2020, 2020, 2109673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, Z.U.; Mobin, K.H.; Siddiqui, Z.A. Pattern of suicide: A descriptive, comparative study conducted in Karachi during period 2011-2015. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences 2017, 11, 865–869. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.; Ashraf, M.F.; Farid, N.; Hashmi, A.M.; Khattak, M.A.; Nishat, M. Risk factors assessment of suicide cases in Punjab Pakistan & medico legal frame work shortcomings in Pakistan related to psychological autopsy -a case control psychological autopsy study. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, V.N.; Godbole, H.V.; Kukde, H.G. Suicidal and homicidal deaths: A comparative and circumstantial approach. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2007, 14, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, V.N.; Kolpe, D.; Tumram, N.; Meshram, S.; Pawar, M.; Kukde, H. Characteristic Features of Hanging: A Study in Rural District of Central India. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Mali, B.; Akter, H. Characteristics of suicidal attempts in Bangla online news portals. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2020, 36, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Mali, B.; Akter, H. Characteristics, methods and precipitating events of suicidal behaviors in Bangladesh: A year-round content analysis of six national newspapers. Neurol. Psychiatry Brain Res. 2020, 36, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Mohit, M.A.; Mullick, M.S.I.; Kabir, R.; Khan, M.M. Risk factors for suicide in Bangladesh: Case–control psychological autopsy study. BJPsych Open 2020, 7, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Mali, B.; Akter, H. Demography and risk factors of suicidal behavior in Bangladesh: A retrospective online news content analysis. Asian J. Psychiatry 2018, 36, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.; Vijayakumar, L.; Pirkis, J.; Jayaseelan, M.; Cherian, A.; Soerensen, J.B.; Arya, V.; Niederkrotenthaler, T. Mass media representation of suicide in a high suicide state in India: An epidemiological comparison with suicide deaths in the population. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e030836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiye, A.; Kapoor, N.; Ahmed, S. An empirical analysis of suicidal death trends in India: A 5 year retrospective study. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2014, 27, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, P.; Gupta, A.; Kumar, R. The psychopathology and the socio-demographic determinants of attempted suicide patients. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2011, 5, 917–920. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, F.; Ara, J.; Kumar, S. Deliberate self poisoning at national poisoning control centre. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sci. 2014, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bastia, B.K.; Kar, N. A Psychological Autopsy Study of Suicidal Hanging from Cuttack, India: Focus on Stressful Life Situations. Arch. Suicide Res. 2009, 13, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, M.S.; Verma, S.K.; Murty, O.P. Suicide Notes: Psychological and Clinical Profile. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2006, 36, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M.S.; Aggarwal, N.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Psychosocial profile of suicide ideators, attempters and completers in India. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2000, 46, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, M.C.; Behere, P.B. Risk Factors for Farmers' Suicides in Central Rural India: Matched Case-control Psychological Autopsy Study. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2016, 38, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, R.; Gnanaselane, J. Correlates of suicidal intent in attempted suicide. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry 2005, 15, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari, V.A.; Das, S.; Sahu, S.K.; Devnath, G.P.; Chandra, A. Epidemio-toxicological profile and reasons for fatal suicidal poisoning: A record-based study in South India. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, R.; Hewagama, M.; Priyangika, W.D.; Range, S.; Karunaratne, S. Study of suicides reported to the Coroner in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Med. Sci. Law 2010, 50, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagaman, A.K.; Khadka, S.; Lohani, S.; Kohrt, B. Suicide in Nepal: A modified psychological autopsy investigation from randomly selected police cases between 2013 and 2015. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017, 52, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Mahato, A.K. Socio-demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients who Attempt Suicide: A Hospital-based Study from Eastern India. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2016, 26, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, N. Profile of risk factors associated with suicide attempts: A study from Orissa, India. Indian J. Psychiatry 2010, 52, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Anand, B.; Devi, M.; Murthy, K. Psychological autopsy of suicide—a cross-sectional study. Indian J. Psychiatry 2005, 47, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.M.; Mahmud, S.; Karim, M.S.; Zaman, M.; Prince, M. Case–control study of suicide in Karachi, Pakistan. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 402–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.M.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, S.R. Female Suicide Rates in Ghizer, Pakistan. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2009, 39, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, A.K.; Singh, U.S.; Singh, R. Autopsy audit of intentional burns inflicted by self or by others in north India-5 year snapshot. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2015, 35, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, U.; Kumar, R.S. Characteristics of suicidal attempts among farmers in rural South India. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2017, 26, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.N.S.; Jayakrishnan Kumari, A.; et al. A case-controlled study of Suicides in an agrarian district in Kerala. Indian J Soc Psychiatry 2011, 27, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Manoranjitham, S.D.; Rajkumar, A.P.; Thangadurai, P.; Prasad, J.; Jayakaran, R.; Jacob, K.S. Risk factors for suicide in rural south India. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 196, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, P.; Ziaian, T. Indian Suicide and Marriage: A Research Note. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2002, 33, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Sahu, G.; Mohanty, M.K.; Patnaik, M. Suicide in India – A four year retrospective study. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2007, 14, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naz, F. Risk factors of successful suicide attempts in Punjab. Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute. 2016, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, V.S.; Bagul, K.R.; Mudgal, V.; Jain, P. Serum Kynurenine Levels in Patients of Depression with and without Suicidality: A Case-control Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkar, S.R.; Nagarsekar, B.; Weiss, M.G. Explaining Suicide in an Urban Slum of Mumbai, India: A sociocultural autopsy. Crisis 2009, 30, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Vijayakumar, L.; Thakur, J.; Gajalakshmi, V.; Gururaj, G.; Suraweera, W.; Jha, P.; Million Death Study Collaborators. Suicide mortality in India: A nationally representative survey. Lancet 2012, 379, 2343–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.S.; Feroz, A.H.; Islam, S.N.; Karim, M.N.; Rabbani, M.G.; Alam, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M.R.; Ahmed, H.U.; Bhowmik, A.D.; Khan, M.Z. Risk Factors of Suicide and Para Suicide in Rural Bangladesh. J. Med. 2014, 14, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadia, S.; Naheed, K.; Tariq, F.; Ghani, M.I.; Zarif, P.; Rafiq, A.; Laique, T. An Audit of Wheat Pill Poisoning in A Tertiary Care Hospital: A Retroscpective Study. Age 2021, 30, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.K.; Biswas, H.; Agarwal, S.K. Risk factors of suicide among patients admitted with suicide attempt in Tata main hospital, Jamshedpur. Indian J. Public Health 2016, 60, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaiq, M.; Ashraf, B. Epidemiology and Outcome of Self-Inflicted Burns at Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences, Islamabad. World J. Plast. Surg. 2014, 3, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Samaraweera, S.; Sumathipala, A.; Siribaddana, S.; Sivayogan, S.; Bhugra, D. Completed Suicide among Sinhalese in Sri Lanka: A Psychological Autopsy Study. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2008, 38, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Arafat, S.M.Y. Demography and Risk Factors of Suicide in Bangladesh: A Six-Month Paper Content Analysis. Psychiatry J. 2017, 2017, 3047025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmin Salam, S.; Alonge, O.; Islam, M.I.; Hoque, D.M.E.; Wadhwaniya, S.; Ul Baset, M.K.; Mashreky, S.R.; El Arifeen, S. The Burden of Suicide in Rural Bangladesh: Magnitude and Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A. Psychological attributes and socio-demographic profile of hundred completed suicide victims in the state of Goa, India. Indian J. Psychiatry 2013, 55, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayakumar, L.; Rajkumar, S. Are risk factors for suicide universal? A case-control study in India. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1999, 99, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, L.; Ali, Z.S.; Umamaheswari, C. Socio cultural and clinical factors in repetition of suicide attempts: A study from India. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health 2008, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øien-Ødegaard, C.; Hauge, L.J.; Reneflot, A. Marital status, educational attainment, and suicide risk: A Norwegian register-based population study. Popul. Health Metr. 2021, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasaju, S.P.; Krumeich, A.; Van der Putten, M. Suicide and deliberate self-harm among women in Nepal: A scoping review. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhani, S.S.; Perveen, S.; Hashmi, D.-E.; Akbar, K.; Bachani, S.; Khan, M.M. Suicide and deliberate self-harm in Pakistan: A scoping review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, N.; Karmaliani, R.; Sullaiman, N.; Bann, C.M.; McClure, E.M.; Pasha, O.; Wright, L.L.; Goldenberg, R.L. Prevalence of suicidal thoughts and attempts among pregnant Pakistani women. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010, 89, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).