Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

13 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Statistical analyses

2.3. Generalized linear model

3. Results

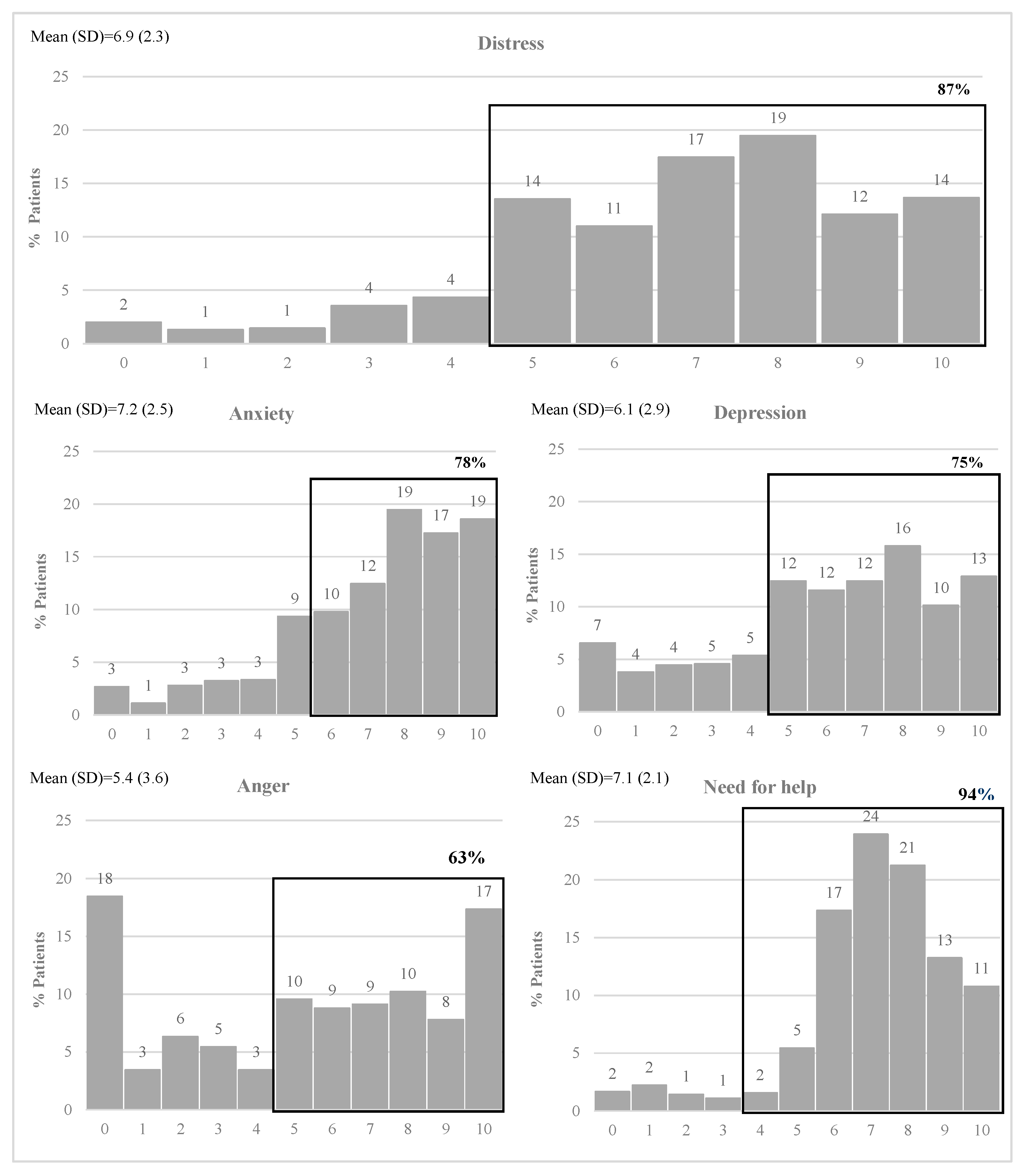

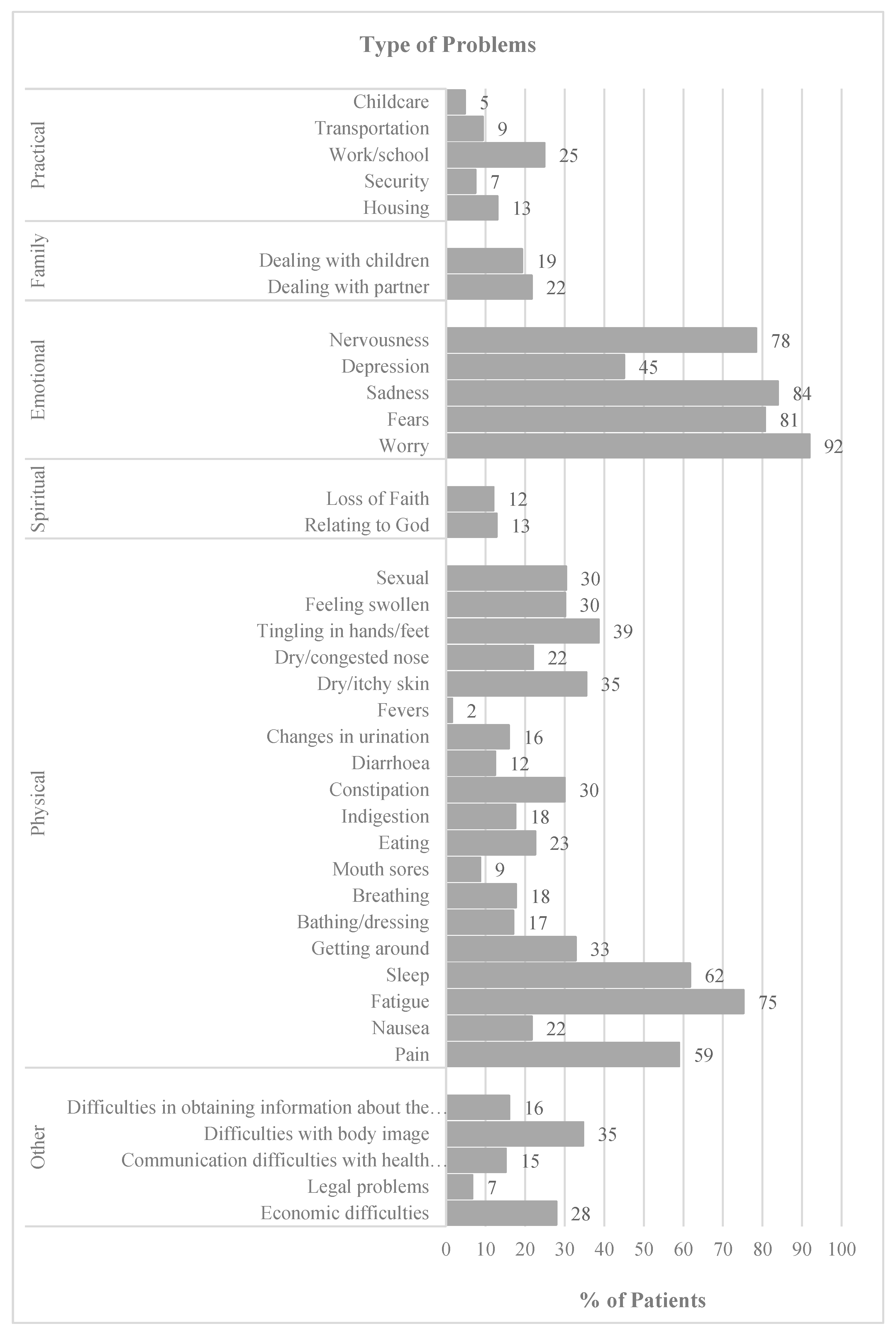

3.1. Descriptive analysis

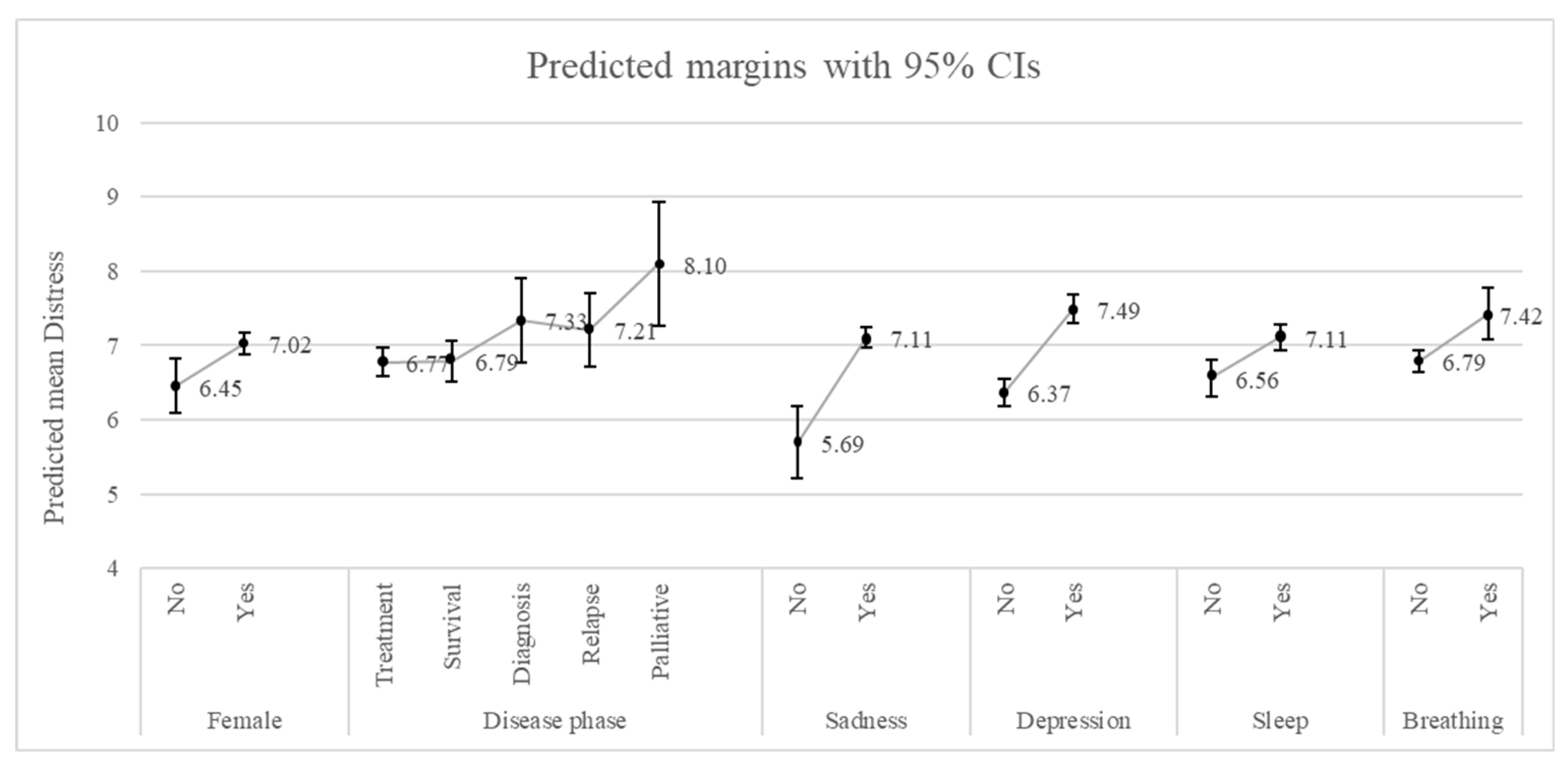

3.2. Generalized linear model

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for clinical practice

4.2. Limitations and future research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay J; Ervik M; Lam F; Colombet M; Mery L; Piñeros M; Znaor A; Soerjomataram I; Bray F Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today - Portugal. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Luigjes-Huizer, Y.L.; Tauber, N.M.; Humphris, G.; Kasparian, N.A.; Lam, W.W.T.; Lebel, S.; Simard, S.; Smith, A. Ben; Zachariae, R.; Afiyanti, Y.; et al. What Is the Prevalence of Fear of Cancer Recurrence in Cancer Survivors and Patients? A Systematic Review and Individual Participant Data Meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Ferguson, D.W.; Gill, J.; Paul, J.; Symonds, P. Depression and Anxiety in Long-Term Cancer Survivors Compared with Spouses and Healthy Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Oncol 2013, 14, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogavero, M.P.; DelRosso, L.M.; Fanfulla, F.; Bruni, O.; Ferri, R. Sleep Disorders and Cancer: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Sleep Med Rev 2021, 56, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unseld, M.; Krammer, K.; Lubowitzki, S.; Jachs, M.; Baumann, L.; Vyssoki, B.; Riedel, J.; Puhr, H.; Zehentgruber, S.; Prager, G.; et al. Screening for Post-traumatic Stress Disorders in 1017 Cancer Patients and Correlation with Anxiety, Depression, and Distress. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 2382–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Chan, M.; Bhatti, H.; Halton, M.; Grassi, L.; Johansen, C.; Meader, N. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Adjustment Disorder in Oncological, Haematological, and Palliative-Care Settings: A Meta-Analysis of 94 Interview-Based Studies. Lancet Oncol 2011, 12, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Q.-U.T.; Ostir, G. V.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Freeman, J.; Goodwin, J.S. Relationship of Depression to Patient Satisfaction: Findings from the Barriers to Breast Cancer Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005, 89, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondryn, H.J.; Edmondson, C.L.; Hill, J.; Eden, T.O. Treatment Non-Adherence in Teenage and Young Adult Patients with Cancer. Lancet Oncol 2011, 12, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, Q.; LIN, Y.; XU, Y.; ZHOU, H. The Impact of Depression and Anxiety on Quality of Life in Chinese Cancer Patient-Family Caregiver Dyads, a Cross-Sectional Study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green McDonald, P.; O’Connell, M.; Lutgendorf, S.K. Psychoneuroimmunology and Cancer: A Decade of Discovery, Paradigm Shifts, and Methodological Innovations. Brain Behav Immun 2013, 30, S1–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, M.H.; Lechner, S.; Diaz, A.; Vargas, S.; Holley, H.; Phillips, K.; McGregor, B.; Carver, C.S.; Blomberg, B. Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management Effects on Psychosocial and Physiological Adaptation in Women Undergoing Treatment for Breast Cancer. Brain Behav Immun 2009, 23, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultz, B.D.; Carlson, L.E. Emotional Distress: The Sixth Vital Sign in Cancer Care. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2005, 23, 6440–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J. Pooled Results From 38 Analyses of the Accuracy of Distress Thermometer and Other Ultra-Short Methods of Detecting Cancer-Related Mood Disorders. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2007, 25, 4670–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Baker-Glenn, E.A.; Granger, L.; Symonds, P. Can the Distress Thermometer Be Improved by Additional Mood Domains? Part I. Initial Validation of the Emotion Thermometers Tool. Psychooncology 2010, 19, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harju, E.; Michel, G.; Roser, K. A Systematic Review on the Use of the Emotion Thermometer in Individuals Diagnosed with Cancer. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 1803–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.J.; Machado, J.C.; Faria, S.; Remondes-Costa, S.; Brandão, T.; Branco, M.; Moreira, S.; Pereira, M.G. Brief Emotional Screening in Oncology: Specificity and Sensitivity of the Emotion Thermometers in the Portuguese Cancer Population. Palliat Support Care 2020, 18, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areia, N.P.; Mitchell, A.; Fonseca, G.; Major, S.; Relvas, A.P. A Visual-Analogue Screening Tool for Assessing Mood and Quality of Daily Life Complications in Family Members of People Living With Cancer: Portuguese Version of the Emotion Thermometers: Burden Version. Eval Health Prof 2020, 43, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampling, J.; Mitchell, A.J.; Von Oertzen, T.; Docker, J.; Jackson, J.; Cock, H.; Agrawal, N. Screening for Depression in Epilepsy Clinics. A Comparison of Conventional and Visual-Analog Methods. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Morgan, J.P.; Petersen, D.; Fabbri, S.; Fayard, C.; Stoletniy, L.; Chiong, J. Validation of Simple Visual-Analogue Thermometer Screen for Mood Complications of Cardiovascular Disease: The Emotion Thermometers. J Affect Disord 2012, 136, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabora, J.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; Curbow, B.; Hooker, C.; Piantadosi, S. The Prevalence of Psychological Distress by Cancer Site. Psychooncology 2001, 10, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Bennett, M.I.; Stark, D.; Murray, S.; Higginson, I.J. Psychological Distress in Cancer from Survivorship to End of Life Care: Prevalence, Associated Factors and Clinical Implications. Eur J Cancer 2010, 46, 2036–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese-Davis, J.; Waller, A.; Carlson, L.E.; Groff, S.; Zhong, L.; Neri, E.; Bachor, S.M.; Adamyk-Simpson, J.; Rancourt, K.M.; Dunlop, B.; et al. Screening for Distress, the 6th Vital Sign: Common Problems in Cancer Outpatients over One Year in Usual Care: Associations with Marital Status, Sex, and Age. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrowatka, A.; Motulsky, A.; Kurteva, S.; Hanley, J.A.; Dixon, W.G.; Meguerditchian, A.N.; Tamblyn, R. Predictors of Distress in Female Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017, 165, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.; Kroska, E.B. Distress Predicts Utilization of Psychosocial Health Services in Oncology Patients. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.; Kruse, H.; Holcomb, L.; Freche, R. Distress and Psychosocial Needs: Demographic Predictors of Clinical Distress After a Diagnosis of Cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2018, 22, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, A.; Hartung, T.J.; Friedrich, M.; Vehling, S.; Brähler, E.; Härter, M.; Keller, M.; Schulz, H.; Wegscheider, K.; Weis, J.; et al. One in Two Cancer Patients Is Significantly Distressed: Prevalence and Indicators of Distress. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, A.; Pourali, L.; Vaziri, Z.; Saedi, H.R.; Behdani, F.; Amel, R. Psychological Distress in Cancer Patients. Middle East J Cancer 2018, 9, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.E.; Zelinski, E.L.; Toivonen, K.I.; Sundstrom, L.; Jobin, C.T.; Damaskos, P.; Zebrack, B. Prevalence of Psychosocial Distress in Cancer Patients across 55 North American Cancer Centers. J Psychosoc Oncol 2019, 37, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, K.J.; Good, L.H.; McKiernan, S.; Miller, L.; O’Connor, M.; Kane, R.; Kruger, D.J.; Adams, B.R.; Musiello, T. “Undressing” Distress among Cancer Patients Living in Urban, Regional, and Remote Locations in Western Australia. Supportive Care in Cancer 2016, 24, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrykowski, M.A.; Cordova, M.J. Factors Associated with PTSD Symptoms Following Treatment for Breast Cancer: Test of the Andersen Model. J Trauma Stress 1998, 11, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, M.; Buunk, B.P.; Kuijer, R.G.; Wobbes, T.; Sanderman, R. Couples Dealing with Cancer: Role and Gender Differences Regarding Psychological Distress and Quality of Life. Psychooncology 2000, 9, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnoll, R.A.; Harlow, L.L. Using Disease-Related and Demographic Variables to Form Cancer-Distress Risk Groups. J Behav Med 2001, 24, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, E.; Byles, J.E.; Gibson, R.E.; Rodgers, B.; Latz, I.K.; Robinson, I.A.; Williamson, A.B.; Jorm, L.R. Is Psychological Distress in People Living with Cancer Related to the Fact of Diagnosis, Current Treatment or Level of Disability? Findings from a Large Australian Study. Medical Journal of Australia 2010, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Rha, S.Y.; Song, S.K.; Namkoong, K.; Chung, H.C.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, G.M.; Kim, K.R. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Psychological Distress among Korean Cancer Patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011, 33, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichler, T.; Marten-Mittag, B.; Hermelink, K.; Telzerow, E.; Frank, T.; Ackermann, U.; Belka, C.; Combs, S.E.; Gratzke, C.; Gschwend, J.; et al. Distress in Hospitalized Cancer Patients: Associations with Personality Traits, Clinical and Psychosocial Characteristics. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, P.J.; Garssen, B.; Visser, A.P.; Duivenvoorden, H.J.; de Haes, H.C.J.M. Early Stage Breast Cancer: Explaining Level of Psychosocial Adjustment Using Structural Equation Modeling. J Behav Med 2004, 27, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.K.; Kaji, A.H.; Roth, K.G.; Hari, D.M.; Yeh, J.J.; Dauphine, C.; Ozao-Choy, J.; Chen, K.T. Determinants of Psychosocial Distress in Breast Cancer Patients at a Safety Net Hospital. Clin Breast Cancer 2022, 22, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschbach, P.; Britzelmeir, I.; Dinkel, A.; Giesler, J.M.; Herkommer, K.; Nest, A.; Pichler, T.; Reichelt, R.; Tanzer-Küntzer, S.; Weis, J.; et al. Distress in Cancer Patients: Who Are the Main Groups at Risk? Psychooncology 2020, 29, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; Ding, S.; Cheng, Q.; Xie, J.; Cheng, A.S. Prevalence and Determinants of Psychological Distress in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer: A Multicenter Survey. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2021, 8, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavery, J.F.; Clarke, V.A. Causal Attributions, Coping Strategies, and Adjustment to Breast Cancer. Cancer Nurs 1996, 19, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.; Brederecke, J.; Franzke, A.; de Zwaan, M.; Zimmermann, T. Psychological Distress in a Sample of Inpatients With Mixed Cancer—A Cross-Sectional Study of Routine Clinical Data. Front Psychol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHoose, L.; Black, L.L.; Doty, K.; Sabata, D.; Twumasi-Ankrah, P.; Taylor, S.; Johnson, R. An Analysis of the Distress Thermometer Problem List and Distress in Patients with Cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer 2015, 23, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.A.; Mahendran, R.; Chua, J.; Peh, C.-X.; Lim, S.-E.; Kua, E.-H. The Distress Thermometer as an Ultra-Short Screening Tool: A First Validation Study for Mixed-Cancer Outpatients in Singapore. Compr Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A. Emotion Thermometers Tool. Available online: http://www.psycho-oncology.info/ET.htm (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- StataCorp GLM – Generalized Linear Models. Available online: https://www.stata.com/manuals/rglm.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Rogers, S.N.; Mepani, V.; Jackson, S.; Lowe, D. Health-Related Quality of Life, Fear of Recurrence, and Emotional Distress in Patients Treated for Thyroid Cancer. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2017, 55, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenimovahed, Z.; Salehiniya, H.; Hadavandsiri, F.; Allahqoli, L.; Günther, V.; Alkatout, I. Psychological Distress Among Cancer Patients During COVID-19 Pandemic in the World: A Systematic Review. Front Psychol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, T.F.; Silva, S.M.; Pacheco, A.F.; de Sousa, B.C.; Pires, C.A.; Dias, A.S.; Costa, A.L.; Mesquita, A.R.; Fernandes, E.E.; Marques, G.F.; et al. Psychological Distress in a Portuguese Sample of Cancer Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Psychosoc Oncol Res Pract 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.W.L.; Chan, F.H.F.; Barry, T.J.; Lam, C.; Chong, C.Y.; Kok, H.C.S.; Liao, Q.; Fielding, R.; Lam, W.W.T. Psychological Distress during the 2019 Coronavirus Disease ( <scp>COVID</Scp> -19) Pandemic among Cancer Survivors and Healthy Controls. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1380–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekolaichuk, C.L.; Cumming, C.; Turner, J.; Yushchyshyn, A.; Sela, R. Referral Patterns and Psychosocial Distress in Cancer Patients Accessing a Psycho-Oncology Counseling Service. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steginga, S.K.; Campbell, A.; Ferguson, M.; Beeden, A.; Walls, M.; Cairns, W.; Dunn, J. Socio-Demographic, Psychosocial and Attitudinal Predictors of Help Seeking after Cancer Diagnosis. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.C.; Jutagir, D.R.; Miller, A.; Nelson, C. Physical Problem List Accompanying the Distress Thermometer: Its Associations with Psychological Symptoms and Survival in Patients with Metastatic Lung Cancer. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner-Teleagă, A.; Kim, Y.-T.; Osel, T.; Richter, K. Sleep Disorders in Cancer—A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, K.K. Use of the Distress Thermometer in Clinical Practice. J Adv Pract Oncol 2019, 10, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, P.B.; Donovan, K.A.; Trask, P.C.; Fleishman, S.B.; Zabora, J.; Baker, F.; Holland, J.C. Screening for Psychologic Distress in Ambulatory Cancer Patients. Cancer 2005, 103, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewett, P.I.; Teoh, D.; Petzel, S.; Lee, H.; Messelt, A.; Kendall, J.; Hatsukami, D.; Everson-Rose, S.A.; Blaes, A.H.; Vogel, R.I. Cancer-Related Distress: Revisiting the Utility of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer Problem List in Women With Gynecologic Cancers. JCO Oncol Pract 2020, 16, e649–e659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Ferreira, G.; Machado, J.C.; Leite, Â. The Indirect Effect of Body Image on Distress in Women with Breast Cancer Undergoing Chemotherapy. Health Psychol Rep 2022, 10, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distress Management Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2003, 1, 344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Patients n=899 N (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 59.9 (12.6) |

| Female | 712 (79.2) |

| Disease phase | |

| Treatment | 438 (48.7) |

| Survival | 291 (32.4) |

| Diagnosis | 80 (8.9) |

| Relapse | 53 (5.9) |

| Palliative | 37 (4.1) |

| Type of Cancer | |

| Breast | 456 (50.7) |

| Colorectal | 74 (8.2) |

| Lung | 50 (5.6) |

| Lymphoma | 42 (4.7) |

| Brain | 27 (3.0) |

| Stomach | 24 (2.7) |

| Thyroid | 22 (2.5) |

| Pancreatic | 17 (1.9) |

| Ovaries | 16 (1.8) |

| Multiple myeloma | 16 (1.8) |

| Prostate | 15 (1.7) |

| Leukaemia | 13 (1.5) |

| Cervical | 12 (1.3) |

| Other | 115 (12.8) |

| Distress | ||

| Marginal effect | Std. Err. | |

| Demographics | ||

| Female | 0.57*** | 0.21 |

| Disease phase | ||

| Treatment | Ref. | |

| Survival | 0.02 | 0.18 |

| Diagnosis | 0.56 | 0.31 |

| Relapse | 0.44 | 0.28 |

| Palliative | 1.33*** | 0.45 |

| Emotional | ||

| Sadness | 1.42*** | 0.27 |

| Depression | 1.13*** | 0.15 |

| Physical | ||

| Sleep | 0.55*** | 0.17 |

| Breathing | 0.63*** | 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).