1. Introduction

Global biodiversity includes more than 350,000 species of known plants [

1], with approximately 30,000 species of edible plants [

2,

3], including wild food plants (WFPs) that grow spontaneously without direct human intention to cultivate them [

4]. Around the world, these plants are used as a main or complementary source of food [

5,

6,

7], mostly by local populations [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Although there is a rich variety of WFP, most of them have unknown or underutilized economic and consumption potential [

12,

13], resulting in a diet that is not very diverse [

14], which negatively affects people's health and nutrition [

15].

WFP consumption brings a series of socioeconomic, nutritional and environmental benefits [

6], especially in regard to sociobiodiversity products. These are nontimber forest products with cultural, social, and religious value that are harvested in natural or managed environments for domestic or commercial purposes [

16]. Various authors have suggested that when native vegetation areas generate income for communities, deforestation pressures tend to decrease [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] because people acknowledge the importance of maintaining biodiversity for their subsistence. This idea is postulated in the conservation by commercialization hypothesis [

22].

Moreover, healthy eating is not only related to consuming adequate food. It is also related to protecting biodiversity and the important historical and cultural value of food [

23]. Therefore, for WFP to increase a population's income without depleting these resources, studies that bring together different theoretical contexts integrating ecology, psychology, and ethnobiology and that can dialog with other sciences are needed. Thus, it can be possible to find the best way to disseminate WFP consumption, protecting its importance to biocultural conservation - conservation not only of biodiversity but also of the practices and values associated with them [

24,

25]. One of the ways to reach novel consumers is to keep them from viewing WFP as unknown or unsuitable for consumption.

The purpose of our research was to identify what interferes with the expectation of products with WFP and the best ways to present products with WFP to potential consumers, aiming at the popularization of WFP. To do this, we take into account factors such as extrinsic cues [

26,

27], the environment with which the product is associated [

28,

29], food neophobia [

30,

31,

32] and the socioeconomic profile [

33,

34,

35,

36]. This work fills gaps in the literature about hypothesis testing involving the expectation around different types of linguistic stimuli and WFP. In addition, this study presents results that can be used as strategies to strengthen WFP popularization programs. Based on this information, the hypotheses proposed here aim to answer the following research question (RQ): What factors interfere with the expectation of products with wild food plants?

1.1. Product Expectations

As demonstrated by Blackmore and collaborators [

37], the way that we communicate and interact with food starts before taste. Everything related to the product (and itself) interferes with our taste, evaluation and intention to buy [

38]. Based on information stored and processed previously by the brain, together with clues newly presented to them about the food available, people make comprehensions and opinions, creating expectations about what they are about to experience [

27,

39]. In the literature, it is possible to find approaches based on psychology that are used frequently to explain consumer behavior and their willingness to try and/or to buy a particular product. One of these approaches is expectation theory [

40].

Using this theory, the authors show that the consumer can create a “sensory expectation” and a “hedonic expectation”. First, consumers believe that the product will be ingested and will have certain sensory characteristics [

40]. This confirmation may or may not occur, which ultimately interferes with the final acceptance of the product [

37,

40]. Hedonic expectations are directly related to the “like or dislike” of the product after tasting it [

40]. However, previous experiences, familiarity, or even the images that are associated with the product can change consumer expectations and/or perceptions about it [

40,

41,

42]. In addition, expectations can be modulated by factors such as extrinsic cues [

37,

43,

44].

1.2. Influence of extrinsic cues on the acceptance of new products

Extrinsic cues are related to the product – price, packaging, label, advertising and place of origin – but do not compose it [

40,

45,

46]. The intrinsic clues, however, are linked to the chemical and sensory properties of the product [

43]. Different senses are linked to the perception of intrinsic and extrinsic clues, which causes them to be processed in different ways in the brain. For example, associations of a new product with one that is already known and accepted by consumers can increase expectations or lead to greater acceptance of the new product. This can be observed in online studies using images and texts [

47,

48].

The description or the name are important factors both in the expectation and in the post-taste evaluation because they can influence the consumer’s preference for the product [

44]. Dishes that are labeled with more descriptive names tend to be viewed with higher quality and provoke more positive attitudes in the sensory experience than dishes labeled with more basic names [

49]. In fact, some anecdotal observations provide important suggestions about the role of nomenclature in the acceptance of new food, such as the case of aroeira (

Schinus terebinthifolia Raddi), a fruit species that is common in northeastern Brazil and known for its medicinal potential [

50]. This fruit became popular in the national and international market as “pink pepper” [

51], so an association with another well-known and used food plant, pepper, was made. Other works have explored different forms of terminological association for the same product, showing how only the description can induce evaluations by consumers [

44,

52]

However, to understand the reasons why terminological associations affect the evaluations of certain products, further studies involving sensory expectations are needed [

44], especially those considering extrinsic factors and not just the perception of sensory attributes [

53]. Ultimately, the name given to a product can influence the consumer's decision-making process. In fact, there are not enough studies specifically aimed at WFP and expectations about a product with this terminological stimulus (its original name). Thus, it is necessary to understand whether other associations of this nature such as associating the product with a name known by the population (conventional plant) can influence the expectation of taste, appropriateness, and willingness to taste. From now on, “taste” will be used when referring to “how tasty the product would be”, and “appropriateness” refers to “how appropriate the product would be”.

Figure 1 presents the model that is proposed in our research. Therefore, we seek to test the following hypothesis:

H1:

The terminological association of an unknown product with a better known product generates greater expectation by the potential consumer.

Prediction:

It is expected that products randomly described with names associated with widely known fruits will be better evaluated in terms of taste expectations, appropriateness and willingness to consume than products randomly described with names of little-known WFPs.

1.3. Expectations and Food-Providing Environments

Among early hominids, vegetable gathering was the basis of food consumption [

54], with a very high intake compared to what is consumed today [

14]. In recent decades, especially after the industrial revolution when everything became fast and practical, urbanization has narrowed the "human-land-food-farming" relationship, distancing the population from consuming natural foods [

55,

56]. Our current way of life impacts our diet, mainly due to a greater intake of products from large monocultures, which makes our food more homogeneous [

57]. Thus, the use of WFP came to be associated with a low social status by a portion of the population [

58] and these foods are often known as "famine foods", which are emergency foods, such as underutilized food plants, that are accessed during times of food scarcity [

59]. In addition, modernization and changes in lifestyle [

60] have driven people to become more concentrated in urban centers, making the distance to collection sites a barrier to WFP consumption and contributing to the erosion of traditional knowledge [

4,

61].

Despite this context, people who like the taste of wild plant species continue to consume them. Others, however, consider these foods old-fashioned and, due to their slow growth, prefer to grow their food or purchase it ready-made [

62]. Modern societies acquire their food mainly through growing crops. Throughout history, these foods have already gone through a process of domestication, allowing them to be suitable for consumption with fewer risks than novel food. In some cases, products associated with "uncultivable" contexts, such as those that are genetically modified or industrially produced, may be seen as less appropriate for consumption or even less tasty. This association is observed in the study by Richetin and collaborators [

63], in which the authors labeled cheese as either industrially produced and pasteurized traditional farm-produced cheese. The results showed a halo effect on the traditional product and a horn effect on the industrially manufactured cheese.

Some authors attribute this process to "delocalization", which is linked to a decrease in the "power" to use local resources due to dependence on more industrial resources or those coming from more distant places [

64]. In view of this, researchers have studied the origin of the product as a factor that interferes with its acceptance and observed that locally sourced products are preferred by consumers [

28,

29]. In addition, the geographic origin of the product has been seen as an indicator of quality; consequently, this influences the creation of different expectations and increases consumers’ willingness to pay [

65,

66]. However, the literature does not specifically provide theories or approaches that are directly linked to different environments and their influence on consumers' expectations of new products. In this sense, other conceptual bases provide a great foundation for conceptualizing our hypothesis. Based on studies that address the "delocalization" process, showing food preferences according to the origin of the product [

46] and studies that show the preference for cultivated foods, it is possible that there are linguistic stimuli that intensify food neophobia, notably in regard to expectations. In this sense, the association with forest environments could be one such stimulus, since most of the known foods are obtained from crops, and the label "from the woods" could further refer to unfamiliar or even inappropriate foods. Therefore, the aim was to test the following hypothesis:

H2:

Linguistically associating an unfamiliar product with a forest environment reduces its expectations compared to products linguistically associated with growing environments.

Prediction:

It is expected that products randomly associated with the "ranch/farm" suffixes will be rated higher on taste expectations, appropriateness and willingness to consume than products associated with "woods/forest" suffixes.

1.4. Food Neophobia and Socioeconomic Characteristics as Modulators of Acceptance of New Products

Food neophobia consists of fear or reluctance to eat different or unfamiliar foods [

32]. Historically, neophobic individuals were less likely to eat harmful foods (toxic products) [

31,

67]. For this reason, neophobia represents a natural protective mechanism and, in this case, is considered advantageous under certain environmental contexts [

31]. Taste buds have evolved to warn us that bitter tastes refer to poisonous products, and sour taste and unpleasant smells refer to spoiled or rotten products [

68]. Therefore, there is a tendency for people to reject foods with these characteristics [

69]. On the other hand, neophobia, especially when coupled with current lifestyles, reduces potential food use forms, further limiting variety in the human diet. In this case, it is disadvantageous [

30,

31]. Researchers point out that food neophobia is touted as behavior that "shapes" the food decisions of humans, varying according to people's age [

70]. Therefore, for these reasons, what was a considerable advantage in stable ancestral environments ended up becoming a barrier, interfering negatively in the popularization of new foods, directly affecting one’s acceptance of a product or willingness to taste it.

In addition to food neophobia, several socioeconomic factors can influence acceptance and willingness to consume new products, such as age, gender, schooling, income and place of residence [

33,

34,

35,

36,

71,

72], given that people from rural areas are less likely to be exposed to unusual foods [

72]. Income is a variable that directly impacts people's relationship with food, since a lower income affects people’s ability to try foods from other cultures, causing people to consume what is more accessible for them in terms of cost‒benefit [

35]. In the literature, the role of gender in food choices is divergent. Some studies have shown that men rate a new food better in terms of taste, suitability and willingness to buy [

73], and others show that women prefer to consume foods that are considered to be healthy [

72]. Multiple factors can modulate and interfere with the expectation of acceptance and the food preference of individuals. Given this, in this study, we sought to test three hypotheses involving food neophobia, socioeconomic aspects, and expectancy ratings for all stimuli:

H3:

Food neophobia and socioeconomic factors explain potential consumers' expectations toward WFP.

Prediction 1:

It is expected that individuals who are more neophobic provide lower ratings for the products presented.

Prediction 2:

It is expected that lower-income individuals provide lower ratings for the products presented.

Prediction 3:

It is expected that older adults provide lower ratings for the products presented compared to younger adults.

Considering the divergence in the literature regarding the role of gender in expectations or acceptance of novel foods, the evaluation of this factor will be exploratory only, without a hypothesis as a starting point.

H4:

Food neophobia positively interferes with the evaluation difference between products associated with a known fruit tree and products associated with WFP.

Prediction:

The difference in evaluation between a product randomly associated with a known fruit tree and a product randomly associated with WFP is expected to be greater among individuals who are more neophobic.

H5:

Food neophobia positively interferes with the evaluation difference between products associated with growing environments and products associated with forest environments.

Prediction:

The difference in evaluation between a product randomly associated with the suffixes "ranch/farm” and a product randomly associated with the suffixes "woods/forest" is expected to be greater among individuals who are more neophobic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Legal Aspects

This study was submitted to and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Alagoas (CAAE 47809221.8.0000.5013) and met the rationale of Article X, Paragraph X.2, of Resolution No. 466/2012 of the National Health Council (see SM1).

2.2. Data Collection through Online Form

To evaluate the expectations of potential consumers about wild fruits, an online form was designed and applied through a market research company (Netquest). In total, 1,000 panelists from around the nation participated in this study, representing the urban and peri-urban population of Brazil with internet access and literacy. The sampling was of the quota type, in which the subsamples by region and gender obeyed the proportion found in the Brazilian population. Our group's computing team (FSQ and NLSS) programmed the form, which was available online during March 2022 until the expected sample size of 1,000 participants was obtained. Initially, participants had access to an explanatory text about the questions they would answer and the Informed Consent Form (ICF). After reading and agreeing to the terms, the participants indicated this option and proceeded with the test. Subsequently, the participants answered questions about their socioeconomic profile (age, gender, schooling, and income), food neophobia, if they have heard of WFP (letter “a” in SM2), if they have tried WFP (letters “b” in SM2), their willingness to taste (letter “c” in SM2) and expectation of appropriateness and taste (letters “d” and “e”, respectively, in SM2). Food neophobia, according to the scale of Pliner and Hobden [

32], was composed of 10 affirmative sentences with answers based on scores from 1 to 7, with extremities 1 "strongly disagree" and 7 "strongly agree" (see SM2). For the questions “a, b and c”, the possible answers were binary (yes or no). For questions “d” and “e”, the answers were given based on a seven-point Likert scale. For the letter “d”, the extreme values were 1 “not appropriate” and 7 “very appropriate”. For the letter “e”, the extreme values were 1 “not tasty” and 7 “very tasty”.

2.3. Randomization of Names and Images

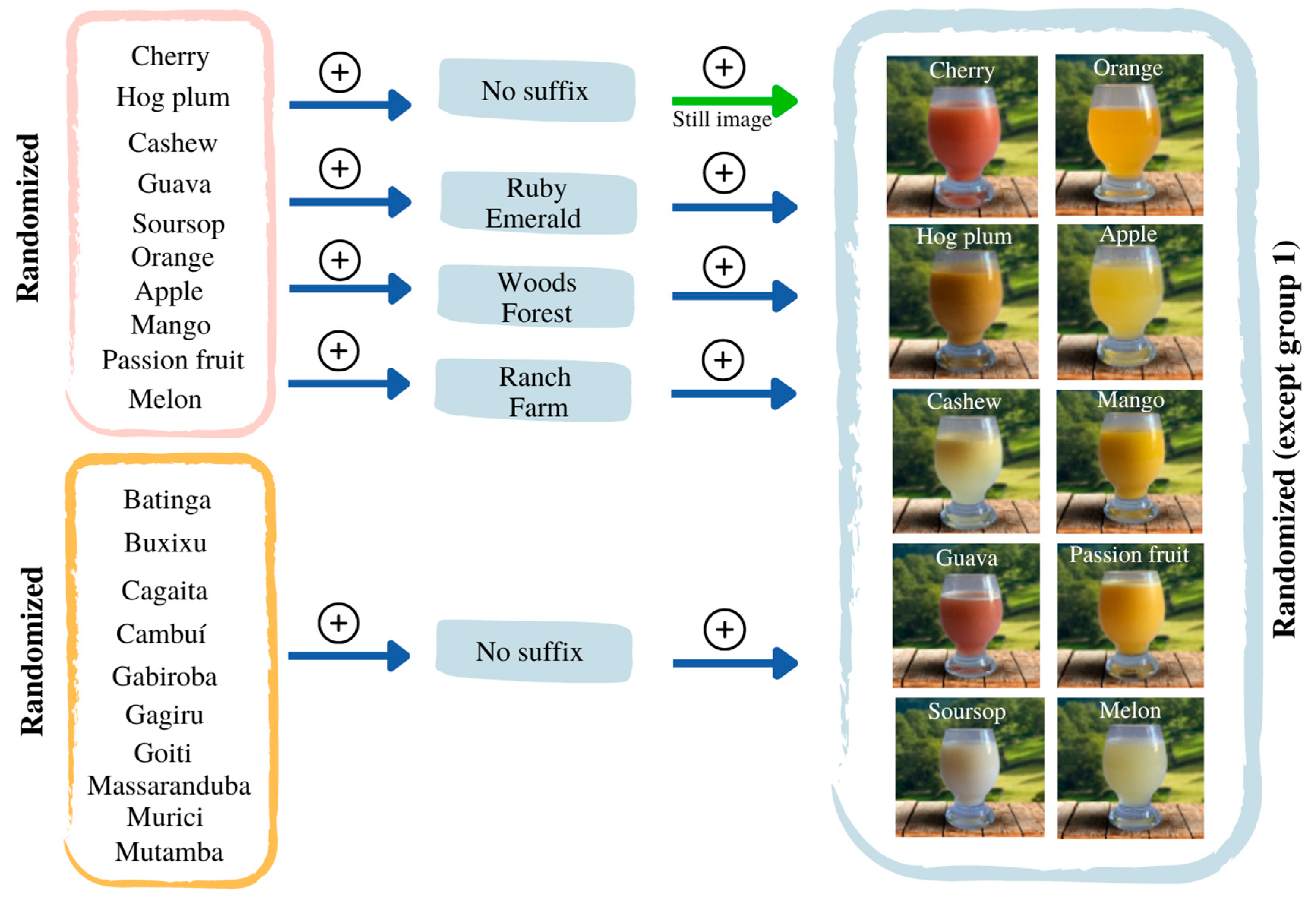

The participants were then given a text to rate their expectations of native fruit-based juices (see SM1) and answered questions associated with products that were randomized as follows (

Figure 2):

Product 1 – programmed to always contain the name of a conventional fruit juice linked to the real photo of this juice.

Product 2 – programmed to randomize the name of the juice of a conventional fruit linked to the, also randomized, suffix “ruby” or “emerald” (names of precious stones chosen to confer association to conventional fruits, such as “cashew-ruby”).

Product 3 – programmed to randomize the name of the juice of a conventional fruit linked to the, also randomized, suffix “woods” or “forest” (used to associate the product with forest environments).

Product 4 – programmed to randomize the name of a conventional fruit juice linked to the, also randomized, suffix “ranch” or “farm” (used to associate the product with growing environments).

Product 5 – a product with a format analogous to the previous one, but with an attention question, instructing the interviewee to mark preestablished multiple choice options. If a participant chose the wrong alternative, they could not complete the form.

Product 6 - programmed to randomize the name of an unconventional fruit juice ("Batinga", "Buxixu", "Cagaita", "Cambuí", "Gabiroba", "Gagiru", "Goiti", "Massaranduba", "Murici", or "Mutamba")

The names of wild plants were chosen arbitrarily, and no criteria were followed. The conventional plants that were chosen are conventional in Brazil. For Products 2, 3, 4, and 6, the picture linked to the juice was randomized from the pictures of the conventional fruit juices so that no interviewee would receive the same photo more than once to illustrate different products. For each product, the participants answered questions about their previous knowledge of each fruit, their intention to consume a derived product, and their expectation regarding taste and appropriateness (see SM2).

2.4. Quality in the Sample Universe

In addition to the attention question, which excluded respondents before they were even recorded as part of the sample, a new three-step quality control process was used to screen the 1.000 responses that were initially included.

Inconsistencies: If the participant answered "no" to the question "Have you ever heard about this plant?" and immediately afterward answered "yes" to the question "Have you ever tasted this fruit or any derivative (juice, jam, etc.)? ", these answers were considered inconsistent, and these people were excluded from our sample, leaving 918 people.

Time taken to answer the questions: After the first exclusion, we excluded from the sample universe the people who answered the questionnaire in less than five or more than 30 minutes, leaving 769 people. This cut was made after we conducted a simulation with participants to verify the average time needed to answer the form.

Date of birth reported with the wrong year: People who indicated their year of birth as 2021 or 2022 were excluded from the sample, leaving 724 people.

Our final sample included 724 participants, with the socioeconomic profile described in

Table 1. However, for each hypothesis, additional filters were applied. For example, for the question "Have you ever tasted this fruit or any derivative (juice, sweet, etc.)?”, we added a filter to remove the effect of a previous experience since the plant does not exist. Then, each hypothesis had more than one statistical test and a different sampling universe (see

Table 2 in "Data analysis") to verify if the result would be different between the two samples.

2.5. Data Analysis

All hypothesis tests were conducted with two sample universes. A "general sample n" that includes all participants and a "filtered sample n" with only those respondents who said they had not tried any of the products to eliminate the effect of possible previous knowledge (even if the products are not real) (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample universe in each hypothesis and tests used in the analyses.

Table 2.

Sample universe in each hypothesis and tests used in the analyses.

| |

General sample n |

Filtered sample n |

Tests conducted |

| H1 |

724 |

380 |

Shapiro‒Wilk, Wilcoxon and chi-square test |

| H2 |

724 |

252 |

| H3 |

724 |

182 |

Stepwise and CLM |

| H4 |

724 |

380 |

Shapiro‒Wilk and Spearman's Correlation |

| H5 |

724 |

252 |

The normality of the data related to Hypotheses 1 and 2 was tested using the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Since the data did not show normality, we performed the Wilcoxon test, a nonparametric method used to compare two paired samples. For H1 and H2 (

Table 2), three indicators were considered based on the participants' expectations: 1) appropriateness; 2) taste; and 3) willingness to taste the product. We performed a chi-square test only for "willingness to taste", as the question allowed binary (yes or no) rather than numerical responses. For this case, a contingency table was created to run the test.

To test Hypothesis 3, we modeled the effect of neophobia and socioeconomic variables (gender, age, schooling, and income) for all terminological stimuli (neutral, wood/forest, ranch/farm, and WFP) based on cumulative linkage models (CLMs). We chose this test because it is appropriate when the response variable is ordinal since it assumes that rank scores have different distances from each other (Christensen, 2022). We used the stepwise approach to identify which variables would remain in the model with the lowest AIC value.

To test H4 and H5, we created a difference evaluation index using the results of the evaluation scores for taste and appropriateness. Considering that each of the variables had possible answers from 1 to 7, this index was calculated based on these scores, following the equations below:

Nap: appropriateness score; Ntt: taste score; N: neutral name (emerald/ruby); WFP: wild food plants; GE: growing environment (ranch/farm); FE: forest environment (woods/forest); IVA: index value for appropriateness; IVT: index value for taste.

The index results were previously tested for normality. Since the data did not show normality, we performed Spearman's correlation test, associating IVA 1 and IVT1 (one per time) with neophobia (H4) and IVA 2 and IVT 2 (one per time) with the food neophobia calculation result (H5).

To calculate the food neophobia score based on this scale, which ranges from 10 to 70, we summed the score received on each item. However, we reversed the order of the items considered reversed (marked with an asterisk in SM2) before calculating.

We performed all analyses using the R program (R Core Team, 2022) version 4.1.2 through RStudio 2022.02.1. For the CLM analysis, we used the package "ordinal" (Christensen, 2019); for boxplot graphs, we used the packages "ggplot2" (Wickham, 2016) and "grid" (R Core Team, 2021); and for correlation graphs, we used "GGally" (Schloerke et al., 2021). Image editing and template creation were done in the free canva version.

2.6. Effect of Photography on Expectations

Although not part of any hypothesis test, a Kruskal‒Wallis test, which compares more than two independent groups when the data do not show a normal distribution, was also performed. We took as independent variables the image (.png) that each participant received and, as independent variables, the scores for appropriateness and taste. Our intention with this effect test was to verify whether the photo had any influence on the scores or if it only served to provide a visual context for the work.

3. Results

3.1. General Characterization of the Results

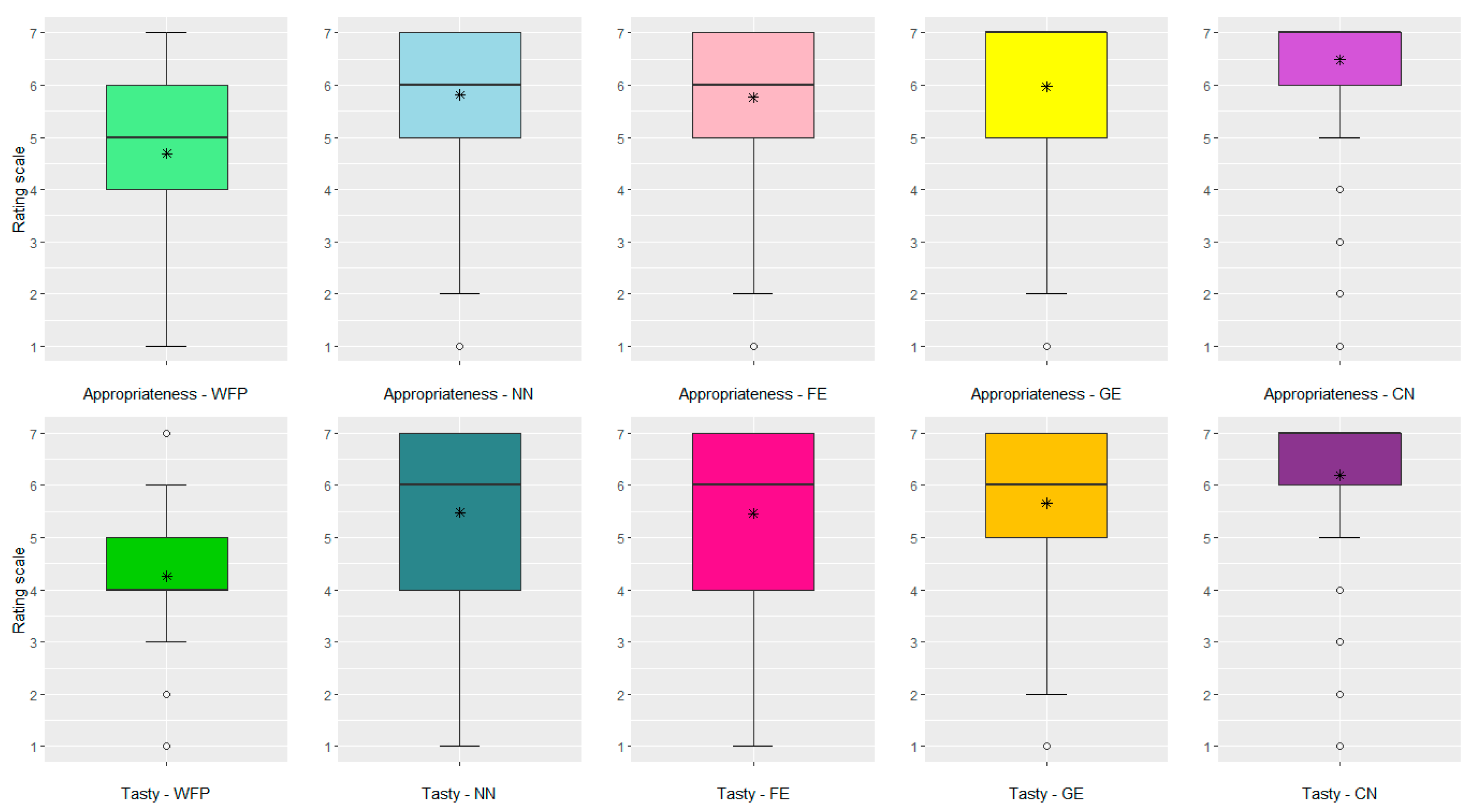

When we observed the results of the general assignment of grades, we realized that the products associated with the terminological stimulus with conventional plant names were better evaluated by the participants, in addition to their grades being more homogeneous (lower standard error values) than the grades attributed to the other terms used (

Figure 3). The lowest scores for appropriateness and taste are associated with the terminological stimulus of wild food plants (WFP). Therefore, the use of names associated with WFP reduced the expectations of appropriateness and taste of the products. Considering the arbitrary choice of the chosen names of the WFP, it seems to us that it did not interfere with the differences in scores assigned by region. In Supplementary materials (SM3), more details regarding the differences between the terminologies by region and socioeconomic aspects of the participants can be seen. In general, using terminological stimuli that are associated with a conventional plant - be it linked to precious stones, forest environments, growing environments - seems to be a good option to encourage people to consume foods derived from wild food plants.

3.2. Taste Expectation Decreases in Products Associated with WFP Names When Compared to the Suffix "Ruby/Emerald"

Evidence was found to be favorable to our first hypothesis. When comparing WFP names to neutral names (ruby or emerald), in both the total and filtered sample universes—excluding people who had previous knowledge—there was a significant difference in taste, appropriateness, and willingness to taste the products (

Table 3). When cutting the sample universe - excluding people who had previous knowledge - to test the terminological stimuli "WFP X neutral suffix", all the results were consistent with the tests carried out with the general sample universe. There was a significant difference in taste expectancy, appropriateness, and willingness to taste across all products. This shows that, whether with or without the prior knowledge effect, the WFP name misleads people into thinking that the product is less tasty than a product with a name that evokes something familiar, such as conventional fruit trees.

3.3. Familiarity with the Growing Environment Favors the Expectation of Appropriateness, Taste, and Willingness to Taste a Product

The tests for Hypothesis 2 show two different results. For the general sample universe (which includes previous knowledge), there was a significant difference in the results for the stimuli from the forest environment vs. the growing environment, considering the three indicators (appropriateness, taste, and willingness to taste). However, after excluding the participants who believed they had already tasted the plant or some derived product (removing previous knowledge from the analyses), no result showed a significant difference (

Table 4). People tend to give better evaluations to products associated with conventional food plants with suffixes of the growing environment than to products presented as conventional plants in association with forest environments because many people think they have already consumed a plant from the ranch or farm. Because these two suffixes “ranch” and “farm” are already well-known terms, they ended up leading people to perceive a certain familiarity with the name of the products.

3.4. CLM Modeling of the Effect of Food Neophobia and Socioeconomic Variables for All Terminological Stimuli

In all the models, food neophobia significantly interfered with all responses for both taste and appropriateness for all stimuli in both sample universes. Socioeconomic factors interfered with the expectancy results for each stimulus in different ways. In some cases, they remained in the model after the stepwise analysis (SM4 and

Table 5) but with low or no significant influence on the participants' expectations. Additional information about the stepwise analysis and complements to the CLM analysis are available in SM4 and SM5, respectively. Although these variables remained in the model, what truly interfered with the expectation of likely consumers was food neophobia.

However, at first, it cannot be specifically said that neophobia interferes with the difference in the scores people gave when evaluating "products associated with conventional plants with neutral name X products associated with WFP". This cannot be said in the case of products associated with "forest environments X growing environments" either, precisely because food neophobia was present and significant in all the models.

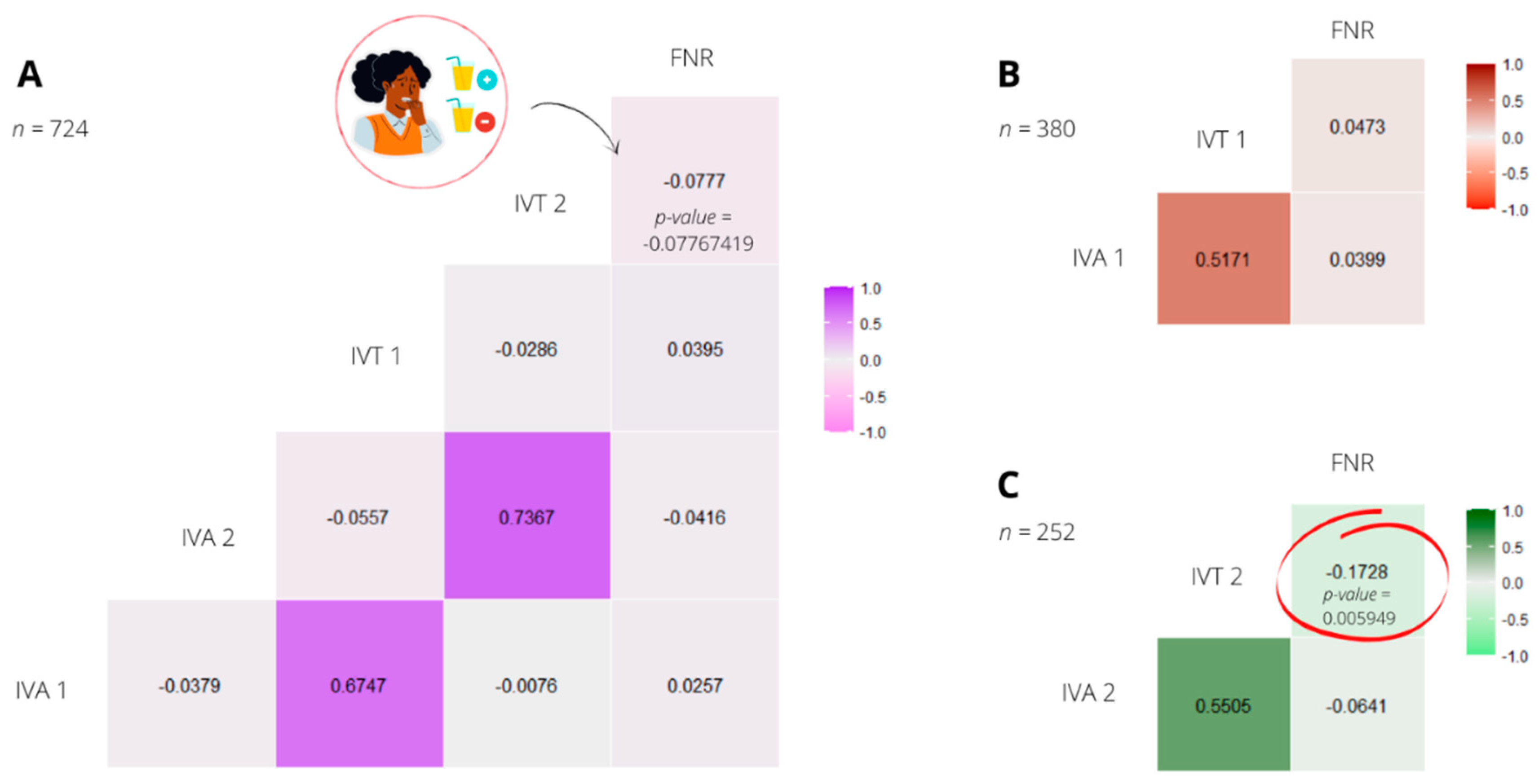

3.5. Spearman's Correlation

The correlation test results in both sample universes show that all correlations between the neophobia score and the indices of the differences between the stimuli were very low. Despite this, the score for IVT 2 ("growing environment - forest environment" scores) correlated with food neophobia was significant (α < 0.05) and negative in both sample universes, both when previous knowledge was present and when previous experience was removed (

Figure 4). The neophobic individuals showed less difference between the two stimuli previously mentioned, and neophilic individuals showed a greater difference between the scores.

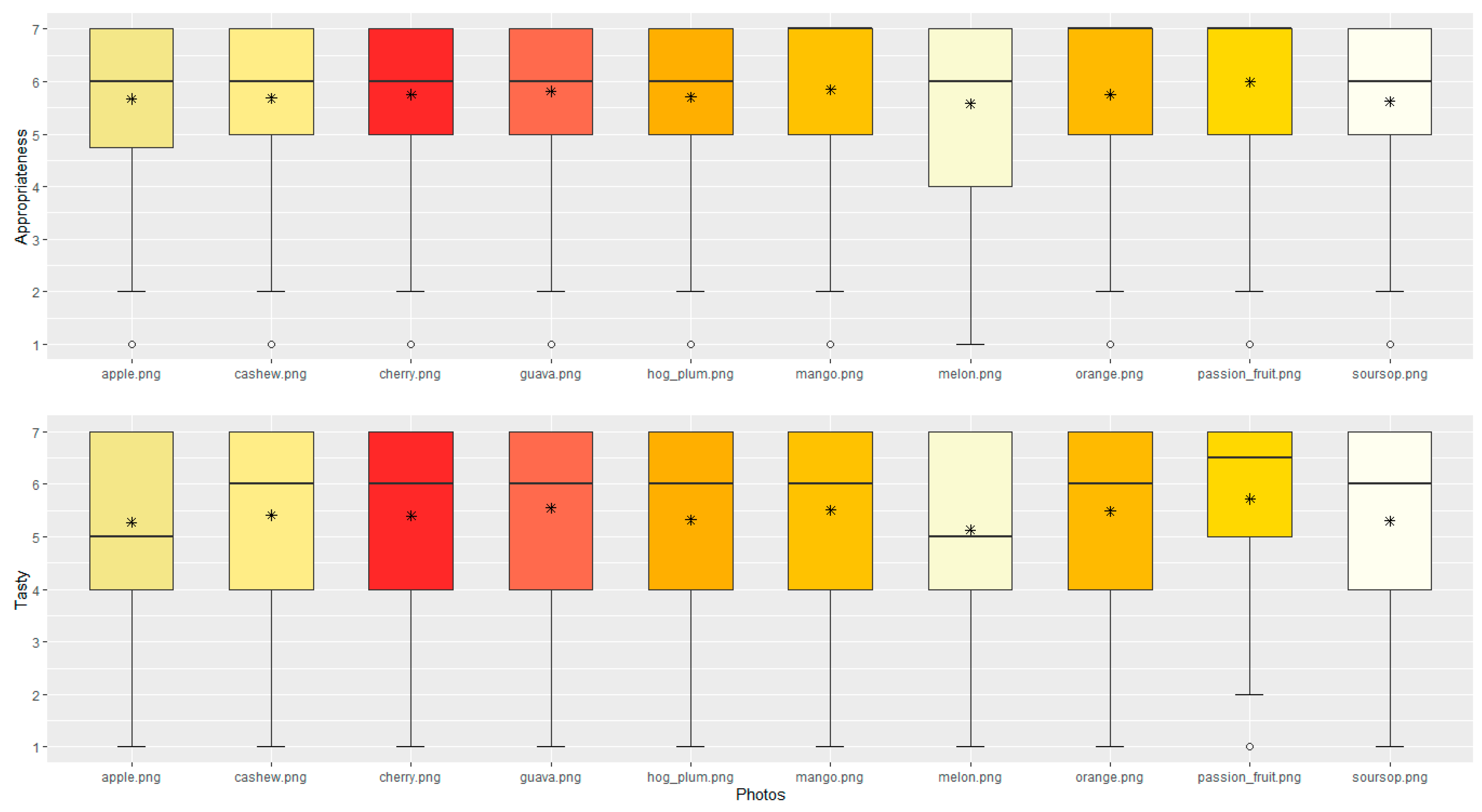

3.6. The Visual Stimulus also Influenced Expectations

The Kruskal‒Wallis test showed that the photo that the participants viewed had an influence on both appropriateness (X²(9) = 23.057; p value = 0.00607) and taste (X²(9) = 37.349; p value = 2.28e-05) expectations. We then performed Dunn's post hoc test to visualize where this difference was present (SM6). Dunn's post hoc test showed that the expectation scores for appropriateness were significantly different only between the "passion fruit" and "melon" images. When examining the results for taste expectation, there was a greater variation of significantly different scores across the images received. The scores differed between cajá and passion fruit, soursop and passion fruit, apple and passion fruit, mango and melon, and passion fruit and melon. Additionally, the best-evaluated pictures can be observed through appropriateness expectations and were orange, mango, and passion fruit, for which most of the scores were seven. Regarding taste expectations, the photo with the best evaluation was passion fruit, whose scores were approximately five to seven (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

4.1. What Aspects Influence Acceptability Expectations about Food Products, after All?

With our results, we can observe that previous knowledge, familiarity and food neophobia are variables that influence consumers' evaluations of expectations in relation to a food product. The phenomenon in which products with names associated with WFP generate a lower expectation of taste, appropriateness and willingness to taste among likely consumers (both those with previous knowledge and those without) probably happened because when evaluations or tasting of specific foods occur, our brains try to make associations between the product and something we have eaten before. For example, when we say that a candy tastes like berries, we quickly associate it with raspberries, strawberries, or cherries [

74] These associations to something familiar can arise based on visuals alone, even if the person has not tasted the food product.

However, the previous knowledge effect by itself can influence the consumer's perception when evaluating certain products, depending on the group of evaluated consumers. For example, using the term UFP (Unconventional Food Plants) did not influence the acceptance of products when potential consumers already had previous knowledge about these plants [

75]. The authors attributed this result to the fact that the participants were students of agrarian sciences courses and were already familiar with the term. However, for people who had no previous knowledge or experience with UFPs, the label resulted in a negative effect. Previous experience is part of adaptive memory and is considered an evolutionary psychological adaptation tool. Coupled with the regularity of exposure, it allowed humans to survive in ancestral environments due to plasticity that causes some information to be highlighted in memory, such as by remembering more dangerous foods [

76]. As our work considered the expectations of potential consumers more broadly, without focusing on a specific group of people, such as students [

75] or fairgoers [

77], our results are more comprehensive and provide more information to support popularization programs.

Another factor that influenced expectations of product acceptability was familiarity. Some of the terminological associations we used induced consumers to be familiar with the products (such as ranch or farm), and subjectively, people indicated that they had previous knowledge about these products. This made people create better expectations about them, showing greater acceptability than when previous knowledge was not present (i.e., excluding from the sample those that claimed to have known the products before). Although they did not work with names on labels but with the color of the packaging, Zellner and collaborators [

74] observed something similar regarding the information previously accessed by the brain. In that study, people related expectations of the taste of products to the color of their packaging, associating it with known flavors. People expected candy wrapped in green packaging to taste like mint. However, when tasting a neutral-colored (white) candy wrapped in one of the colored papers, the real taste was different from what was reported just based on expectation. They associated the taste directly with the intrinsic properties of the product and not the extrinsic properties (color of the wrapping).

Thus, previous experiences and expectations are strong drivers of consumer perceptions, attitudes and behaviors from comparisons between the stimulus received and the cognitive information previously accessed [

43]. Unlike when the consumer has already had previous experience with novel products, the expectations that consumers create can be adapted because they do not yet know what to expect [

78]. In our study, the product presented was juice, which is familiar to all people; this was an assertive choice since our intention was to test the expectation of the associated name and not the product itself. If a different/uncommon product were used, it could present some bias in the results.

Among the other variables tested (food neophobia, income, age and gender), food neophobia was the one that most influenced the expectation of product acceptability, negatively influencing the expectation of taste and appropriateness. Other studies also indicate food neophobia as the principal variable with a significant effect on low taste and appropriateness expectations toward novel foods, attributed to the fact that people have not had prior exposure to these foods [

79,

80]. When an individual is neophobic, there is a tendency for him or her to assign a low score to a specific product regardless of the name associated with it simply because he or she has not yet tried that product. Neophilic individuals, on the other hand, tend to assign higher scores to products associated with things familiar to them. It is worth remembering that neophilic individuals are those who like and go in search of trying new or different things frequently [

81,

82].

Income showed no significant influence on appropriateness and taste expectation. This is an interesting result, considering that, in sensory evaluation studies, income always appears to be a factor that modulates, for example, purchase intention [

83]. Age, on the other hand, showed influence in relation to taste and appropriateness, corroborating Torri et al. [

73], who found that it influenced product expectancy so that appropriateness, expected taste, and willingness to buy decreased as the age of respondents increased.

In addition, other characteristics reveal how people evaluate some products based on vision, such as color [

74,

84], the shape of the product, the container in which it is presented [

84], or the image associated with the label [

85]. The implication of this becomes more evident when participants evaluate the expectation based only on the image, without having the option to taste the product. In an online study, Jaud and Melnyk [

85] evaluated the presence of text and images (together or separately) on wine labels. They found that when labels present the association of "text + image", the evaluations of taste expectancy and purchase intention are better than when there is only text. The image also has an affective appeal that ends up representing an effect on expectation. Although our additional test showed that the photo influenced expectations (more about taste than appropriateness), it did not interfere negatively with our overall results because both the terms used and the distribution of the photos to the participants were randomized, thus reducing any bias that could exist if the photos and terms followed a specific order.

4.2. Strategies for Popularizing WFP: Cultural Identity X Association with Known Fruit Trees

Given our expected results, a basis can be drawn for what strategies can then be used to circumvent food neophobia and popularize WFP-based foods. To develop these strategies, terminology associations may be considered, as tested here. According to studies, to reduce food neophobia, associations of the new product name with something already known can be made [

52,

86]. These terminological associations can broaden the interest in new products. However, on the other hand, this would cause a cultural "disengagement" that would start in the name of the product, as happened with açaí. This typical fruit from the Brazilian Amazon was popularized from the moment it was prepared in association with conventional products, without any relation to its traditional form of use. Today, açaí is more directly associated with physical exercise than with local communities [

87]. Wild fruit popularization involves many socioeconomic benefits. Examples include expanding the forms of use, reaching more distant markets, and increasing the income of extractivists. On the other hand, if the WFP undergoes associations of this nature, as happened with açaí, it will lose its cultural connection. In the exemplary case, reaching international markets did not contribute to the biocultural conservation of the species, considering that the new consumers do not even know its origins or how the local population uses the fruit [

88].

Something that is becoming increasingly common about food is that the food industry is looking for new or different berries to enhance dishes or products. In Sweden, a species of wild blackberry (

Rubus caesius L.) has been popularized, from the local to the national level, with its popular name but in the form of jelly. Today, a typical Swedish dish is composed of this ingredient that gained greater visibility after being used in the Nobel Prize celebration in 2014. Since then, other food products have been created with the same species (balsamic vinegars, ice cream, chutney) [

89]. To date, this popularization has brought many socioeconomic benefits to the region, and the existing demand has not caused any harm to the environment. However, to popularize wild fruits, efforts should be made in relation to investment in strengthening programs for the extractivists of wild fruit species with continuous monitoring. This assists in the mode of production, harvest, and trade and contributes to the maintenance of values and practices associated with the extractivism of these plants.

4.3. Implications for Biocultural Conservation

Our results show that products associated with WFP can be used by the population, as the products were well evaluated based on expectations. Therefore, directly or indirectly, extractivists can also benefit from the use of these plants by implementing their family income. According to Hunter et al. [

90], smallholder farmers, extractivists, and various traditional communities maintain the use of these plants not only for food security but also to perpetuate their culture. Then, given the premises of biocultural conservation [

91], it is important to develop strategies that seek to both protect biodiversity and make it maintainable within social-ecological systems. This may be accomplished by valorizing these sociobiodiversity products as a source of income for the population, with the management of WFP being a good option [

4]. To value local popular knowledge brings people closer and improves their relationship with nature, providing greater accessibility to natural resources and, consequently, greater food diversification without the need to constantly access markets.

However, some considerations should be made relevant to the intentions of popularizing wild plant species. As seen in our results, using the original name of the plant provoked more negative feedback from the participants. How can we suggest that these species are key to cultural and biocultural appreciation if their names do not seem to contribute to this? In fact, this is a very relevant issue to discuss. On the one hand, using the original names of the plants contributes to the strengthening of a valorization of traditional culture based on associated local knowledge (knowledge that has been eroding) [

5]. On the other hand, delinking the use of these plants from their culture and traditionalism seems necessary if the intention is to expand the use of wild plants.

In this sense, directions in light of biocultural conservation can be followed. First, extractivists can continue to use the original names of the wild plants, considering that the sale of the fruits in natura in the places where these plants naturally occur already happens and is well accepted by the local community (i.e. cambuí juice and araçá juice). Second, to popularize these species, it can be interesting to follow some marketing and advertising strategies for the presentation of the product, such as making associations in terms of similarity (appearance, flavor) to conventional plants and thus bringing some familiarity to the consumers. For example, "This is araçá juice, but it resembles guava juice.” The popularization of açaí, for example, was greatly influenced by the power of the media, in which both TV and the internet collaborated in spreading the use of this fruit species [

88,

92]. Third, it is necessary to push for and assist in the sustainable management of WFP by integrating communities holding local ecological knowledge about these plants [

93] into conservation projects so that this link between PAS and their biocultural heritage is perpetuated [

94]. Moreover, these incentives (economic and environmental) for local residents to continue using WFP contribute to the maintenance of increasingly threatened knowledge, stimulating a greater interaction between people and nature [

56].

5. Conclusions

Our results show that the use of terms associated with wild food plants generates lower expectations among consumers who are not familiar with these fruit trees, inducing them to think that the product is less tasty than those with familiar names. For the most part, this is due to the level of food neophobia that these people have. This variable was the one that most influenced our results.

Evidence was found in favor of Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3, while H4 and H5 were refuted. When people who said they were familiar with the products were removed from the sample, the juices associated with conventional plants and cultivated environments did not present higher expectation scores than the products associated with conventional plants and forest environments. Rather than one negative effect of the forest environment on expectation, a positive effect of the growing environment was observed because it induces familiarity with the food.

In our experiment, the focus was not on a specific group of potential consumers. Rather, the study included a general sample of the Brazilian population, providing more comprehensive information. Therefore, based on the participants' expectations, our results point to two main points: 1) Whether considering the effect of prior knowledge or not, our results show that conventional plant names with other suffixes were rated more highly than products associated with WFP. 2) Another question considered is "to whom" these products can be targeted. Having knowledge about the characteristics of the potential consumer groups can make the popularization program successful or unsuccessful. After all, more specific knowledge about human behavior is necessary to understand the processes that determine people's food choices. In this case, multidisciplinary research plays an important role [

78].

Overall, socioeconomic variables, except for income, interfere with consumer expectations. Food neophobia interferes most strongly with evaluation expectations for each linguistic stimulus individually. However, neophobia does not interfere with the fact that a product with the “from the woods” stimulus received a low score or with the fact that a product associated with the “from the ranch” stimulus received a higher score. Therefore, when a product does not have a name that is familiar to consumers, neophobia will always be a barrier to a good evaluation. In this sense, to circumvent this neophobia, new products can have terminological associations with popular fruit species or make other associations of this nature.

As a strategic alternative to starting popularization programs, the following paths are recommended: for cultural valorization, the products can be presented with their original names (WFP names) and cultural backgrounds, but we can make associations with known fruit species to help more distant consumers become familiar with the products. Additionally, strategies can be more targeted, considering the profile of the consumers (neophobic or neophilic). For example, labels that emphasize novelty for neophilic consumers and labels that relate to familiarity for individuals who are more neophobic can be used [

95].

6. Suggestions and Future Implications

This paper was designed considering only expectancy. However, our findings and hypothesis testing represent a good basis for further studies on linguistic interference in the expectation of product evaluation. To cover a gap between expectation and reality, future research is needed to effectively test the acceptability of products with different linguistic stimuli from sensory evaluations considering expectation and actual (post-tasting) taste. In these studies, the confirmation or disconfirmation of consumer expectations can be evaluated. Incidentally, incorporating expectations into sensory evaluation studies is important because it will allow a better understanding of consumer responses [

44].

Based on what we observed in our additional test, future studies may test the interference of the image received (or the product seen) by each participant on their taste expectations, appropriateness, and willingness to taste and pay for the product, with the intention of to determine what exerts the greatest influence on consumer expectations: the name or the image of the product.

Researchers may conduct other studies with WFP to test the terminological stimuli used in our research with suffixes unfamiliar to the population. Examples include associating the name of a conventional plant with a wild plant, whether real or invented. It would be interesting to use unknown suffixes to reduce the number of people who may report having already tasted the fruit or a derived product. In this way, the final universe of the sample can be expanded. In addition, as a way to assist in better economic development, researchers can develop studies focused on the production chain of WFP. Based on this diagnosis and the identification of the best ways to present a new food product to consumers, it will be possible to generate strategies to boost the commercialization of these native fruits. In this way, extractivists can benefit, and the use of these plants can propagate biocultural diversity.

7. Limitations

The sample universe to H2 and H5 was very small, with only 252 responses in these tests out of a total of 1.000 responses collected. This reduction occurred because many participants informed researchers that they had already tasted fruits with the name associated with the cultivation suffix (ranch or farm), such as "ranch apples" or "farm mango". In this case, there was an induction to a familiarity with these terms since they are associated with easily known growing environments. In this sense, one limitation of our study was the choice of these terms without considering that any fruit could come from a ranch or farm, which would intuitively make participants associate them with something common.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, SM1: Ethics Committee Document, SM2: Questionnaire model used in the online expectancy tests, SM3: Mean, standard deviation, median and standard error of the result of food neophobia by region, income, schooling and gender, SM4: Stepwise approach test results, SM5: CLM analysis add-nos, SM6: Results of the Kruskal‒Wallis test and Dunn's test to verify the influence of images on all stimuli

Author Contributions

ÉS: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology, Writing - original draft. DB, DG, GS, RC: Methodology; Writing - original draft. FQ, NS: Program; Writing - original draft preparation. RS: Supervision; Writing - review and editing; Supervision. PM: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal analysis; Writing - revision and editing; Supervision.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by Brazilian Fund for Biodiversity - FUNBIO and HUMANIZE (Grants "FUNBIO Conserving the Future", awarded to EMCS, no. 030/2021), Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior/CAPES (Granting a doctoral scholarship to EMCS), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico/CNPq (PMM, 442810/2016-4, 302786/2016-3), L'Oreal Brasil (For Women in Science Awards) and L'Oreal (International Rising Talents Awards).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Post Graduation Program in Biological Diversity and Conservation in the Tropics, of the Federal University of Alagoas, which gave us the opportunity to develop this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WFO World Flora Online Available online:. Available online: http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Shahid, M.; Singh, R.K.; Thushar, S. Proximate Composition and Nutritional Values of Selected Wild Plants of the United Arab Emirates. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO The Second Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; Rome, 2010; ISBN 9789251065341.

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Forest as Stronghold of Local Ecological Practice: Currently Used Wild Food Plants in Polesia, Northern Ukraine. Econ. Bot. 2018, 72, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, H.-F.; Chen, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-H. Collection Calendar: The Diversity and Local Knowledge of Wild Edible Plants Used by Chenthang Sherpa People to Treat Seasonal Food Shortages in Tibet, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, D.L.; Ferreira, R.P.S.; Santos, E.M.C.; Silva, R.R.V.; Medeiros, P.M. Local Criteria for the Selection of Wild Food Plants for Consumption and Sale in Alagoas, Brazil. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2020, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, C.; Merow, C.; Trisos, C.H. Climate Change Risk to Southern African Wild Food Plants. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, I.M.; de Mello Amorozo, M.C.; Neto, G.G.; Oldeland, J.; Damasceno-Junior, G.A. Knowledge and Use of Wild Edible Plants in Rural Communities along Paraguay River, Pantanal, Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.H.; Yadav, S.; Takahashi, T.; Łuczaj; D’Cruz, L.; Okada, K. Consumption Patterns of Wild Edibles by the Vasavas: A Case Study from Gujarat, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14. [CrossRef]

- Geraci, A.; Polizzano, V.; Schicchi, R. Ethnobotanical Uses of Wild Taxa as Galactagogues in Sicily (Italy). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2018, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayabaşı, N.P.; Tümen, G.; Polat, R. Wild Edible Plants and Their Traditional Use in the Human Nutrition in Manyas (Turkey). Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2018, 17, 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Woolston, C. Healthy People, Healthy Planet: The Search for a Sustainable Global Diet. Nature 2020, 588, S54–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros Jacob, M.C.; Araújo de Medeiros, M.F.; Albuquerque, U.P. Biodiverse Food Plants in the Semiarid Region of Brazil Have Unknown Potential: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2020, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, E.H.; Ladio, A.; Raffaele, E.; Ghermandi, L.; Sanz, E.H. Malezas Comestibles. Hay Yuyos y Yuyos... Rev. Divulg. Científica y Tecnológica la Asoc. Cienc. Hoy 1998, 9, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fanzo, J.; Davis, C.; McLaren, R.; Choufani, J. The Effect of Climate Change across Food Systems: Implications for Nutrition Outcomes. Glob. Food Sec. 2018, 18, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R.P.; Hirsch, E. Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: Review and Analysis of Research; 1st ed.; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2000; ISBN 979876451X. [Google Scholar]

- Coradin, L.; Siminski, A.; Reis, A. Espécies Nativas Da Flora Brasileira de Valor Econômico Atual Ou Potencial: Plantas Pra o Futuro; 2018; ISBN 9788577381531.

- Dias, H.M.; Soares, M.L.; Neffa, E. ESPÉCIES FLORESTAIS DE RESTINGAS COMO POTENCIAIS INSTRUMENTOS PARA GESTÃO COSTEIRA E TECNOLOGIA SOCIAL EM CARAVELAS, BAHIA (BRASIL). Ciência Florest. 2014, 3, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditt, E.; Neiman, Z.; Cunha, R.S. da; Rocha, R.B. da Conservação Da Biodiversidade Por Meio Da Atividade Extrativista Em Comunidades Quilombolas. Rev. Bras. Ciências Ambient. 2013, 1–15.

- Mota, D.M. da; Schmitz, H.; Silva Júnior, J.F. da; Rodrigues, R.F. de A. ; Alves, J.N.F. O Extrativismo de Mangaba é “Trabalho de Mulher”? Duas Situações Empíricas No Nordeste e Norte Do Brasil. Novos Cad. NAEA 2008, 11, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MURALI, K.S.; SHANKAR, U.; SHAANKER, R.U.; GANESHAIAH, K.N.; BAWA, K.S. Extraction of Non-Timber Forest Products in the Forests of Biligiri Rangan Hills, India. 2. Impact of NTFP Extraction on Regeneration, Population Structure, and Species Composition. Econ. Bot. 1996, 52, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.I. Evans, M.I. Conservation by Commercialization. In Tropical forests, People and Food: Biocultural Interactions and Applications to Development; Hladik, M., Hladik, C.M., Linares, A., Pagezy, O.F., Semple, H., Hadley, A., Eds.; UNESCO, Paris and Parthenon Publishing Group, 1993; pp. 815–822.

- BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Alimentos Regionais Brasileiros; 2nd ed.; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, 2015; ISBN 8533404921.

- Gavin, M.C.; McCarter, J.; Mead, A.; Berkes, F.; Stepp, J.R.; Peterson, D.; Tang, R. Defining Biocultural Approaches to Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarter, J.; Sterling, E.J.; Jupiter, S.D.; Cullman, G.D.; Albert, S.; Basi, M.; Betley, E.; Boseto, D.; Bulehite, E.S.; Harron, R.; et al. Biocultural Approaches to Developing Well-Being Indicators in Solomon Islands. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzù, M.F.; Marozzo, V.; Baccelloni, A.; De’ Pompeis, F. Measuring the Effect of Blockchain Extrinsic Cues on Consumers’ Perceived Flavor and Healthiness: A Cross-Country Analysis. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B.; Spence, C. Sensory Expectations Based on Product-Extrinsic Food Cues: An Interdisciplinary Review of the Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Accounts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, L.; Fernqvist, F.; Tjärnemo, H. Consumer Preferences for Domestic and Organically Labelled Vegetables in Sweden. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. C — Food Econ. 2007, 4, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Font i Furnols, M.; Sañudo, C.; Montossi, F.; Oliver, M.A.; Guerrero, L. Spanish, French and British Consumers’ Acceptability of Uruguayan Beef, and Consumers’ Beef Choice Associated with Country of Origin, Finishing Diet and Meat Price. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaapila, A.; Tuorila, H.; Silventoinen, K.; Keskitalo, K.; Kallela, M.; Wessman, M.; Peltonen, L.; Cherkas, L.F.; Spector, T.D.; Perola, M. Food Neophobia Shows Heritable Variation in Humans. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaapila, A.; Silventoinen, K.; Broms, U.; Rose, R.J.; Perola, M.; Kaprio, J.; Tuorila, H.M. Food Neophobia in Young Adults: Genetic Architecture and Relation to Personality, Pleasantness and Use Frequency of Foods, and Body Mass Index-A Twin Study. Behav. Genet. 2011, 41, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiselman, H.L.; King, S.C.; Gillette, M. The Demographics of Neophobia in a Large Commercial US Sample. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Phan, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T. Evaluating the Purchase Behaviour of Organic Food by Young Consumers in an Emerging Market Economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddephatt, J.A.; Keenan, G.S.; Fielden, A.; Reaves, D.L.; Halford, J.C.G.; Hardman, C.A. ‘Eating to Survive’: A Qualitative Analysis of Factors Influencing Food Choice and Eating Behaviour in a Food-Insecure Population. Appetite 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; van Tilburg, W.A.P.; Mei, D.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C. Hungering for the Past: Nostalgic Food Labels Increase Purchase Intentions and Actual Consumption. Appetite 2019, 140, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, H.; Hidrio, C.; Yeomans, M.R. A Taste of Things to Come: The Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cues on Perceived Properties of Beer Mediated by Expectations. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; van den Puttelaar, J.; Verain, M.C.D.; Veldkamp, T. Consumer Acceptance of Insects as Food and Feed: The Relevance of Affective Factors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsics, F.; Megido, R.C.; Brostaux, Y.; Barsics, C.; Blecker, C.; Haubruge, E. Could New Information Influence Attitudes to Foods Supplemented with Edible Insects? Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2027–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliza, R.; Macfie, H.J.H. The Generation of Sensory Expectation by External Cues and Its Effect on Sensory Perception and Hedonic Ratings: A Review. J. Sens. Stud. 1996, 11, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollar, R.; Gil, I.; Lidón, I.; Martín, J.; Fernández, M.J.; Rivera, S. How Material, Visual and Verbal Cues on Packaging Influence Consumer Expectations and Willingness to Buy: The Case of Crisps (Potato Chips) in Spain. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, S.; Pohjanheimo, T.; Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Křečková, Z.; Otterbring, T. The Effects of Consumer Knowledge on the Willingness to Buy Insect Food: An Exploratory Cross-Regional Study in Northern and Central Europe. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A. V. Measuring Consumer Expectations to Improve Food Product Development; Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2007; ISBN 9781845690724.

- Fernqvist, F.; Ekelund, L. Credence and the Effect on Consumer Liking of Food - A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 32, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, H.; Hidrio, C.; Godineau, P.; Yeomans, M.R. The Effect of Implicit and Explicit Extrinsic Cues on Hedonic and Sensory Expectations in the Context of Beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, R.; Quester, P. Tasting Quality: The Roles of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Cues. Asia Pacific J. Mark. Logist. 2009, 21, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahl, S.; Strack, M.; Weinrich, R.; Mörlein, D. Consumer-Oriented Product Development: The Conceptualization of Novel Food Products Based on Spirulina (Arthrospira Platensis) and Resulting Consumer Expectations. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, F.; Hartmann, C.; Siegrist, M. Consumers’ Associations, Perceptions and Acceptance of Meat and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 87, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, M.; Lynn, A. The Effects of Restaurant Menu Item Descriptions on Perceptions of Quality, Price, and Purchase Intention. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2008, 11, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.J.; Gomes, M.A.O.; Jesus, N.B. de Aspectos Socioambientais Da Atividade Extrativista de Produtos Florestais Não Madeireiros: Os Casos Da Fava-D´Anta (Dimorphandra Sp) e Da Aroeira-Da-Praia (Schinus Terebinthifolius Raddi). In Árvores de valor e o valor das árvores: pontos de conexão; Albuquerque, U.P. De, Hanazaki, Ed.; NUPEEA: Recife, 2010; pp. 61–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, N.B. de; Gomes, L.J. Conflitos Socioambientais No Extrativismo Da Aroeira (Schinus Terebebinthifolius Raddi), Baixo São Francisco - Sergipe/Alagoas. Ambient. e Soc. 2012, 15, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, I.; Vallen, B.; Robinson, S.R. The Impact of Product Name on Dieters’ and Nondieters’ Food Evaluations and Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.E.; Jervis, S.M.; Drake, M.A. Examining Extrinsic Factors That Influence Product Acceptance: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, R901–R909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazoyer, M.; Roudart, L. História Das Agriculturas No Mundo: Do Neolítico à Crise Contemporânea; Editora UNESP; NEAD: São Paulo e DF, Brasília, 2010; Volume 69, ISBN 9788571399945. [Google Scholar]

- BRASIL Hortaliças Não-Convencionais: (Tradicionais); Secretaria de Desenvolvimento Agropecuário e Cooperativismo, 2010.

- Leal, M.L.; Alves, R.P.; Hanazaki, N. Knowledge, Use, and Disuse of Unconventional Food Plants. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinupp, V.F.; Lorenzi, H. Plantas Alimentícias Não Convencionais (PANC) No Brasil: Guia de Identificação, Aspectos Nutricionais e Receitas Ilustradas.; 1st ed.; Instituto Plantarum de Estudos da Flora: São Pualo, 2014.

- Baldermann, S.; Blagojević, L.; Frede, K.; Klopsch, R.; Neugart, S.; Neumann, A.; Ngwene, B.; Norkeweit, J.; Schröter, D.; Schröter, A.; et al. Are Neglected Plants the Food for the Future? CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2016, 35, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, V.T.; da Silva Vasconcelos, M.A.; Maciel, M.I.S.; Albuquerque, U.P. Famine Foods of Brazil’s Seasonal Dry Forests: Ethnobotanical and Nutritional Aspects. Econ. Bot. 2012, 66, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, D.; Sharma, A.; Uniyal, S.K. Why They Eat, What They Eat: Patterns of Wild Edible Plants Consumption in a Tribal Area of Western Himalaya. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.L.; Ferreira, R.P. dos S.; Santos, É.M. da C.; Silva, R.R.V. da; Medeiros, P.M. de Local Criteria for the Selection of Wild Food Plants for Consumption and Sale in Alagoas, Brazil. Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2020, 9, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J.; Morales, R. The Gathering and Consumption of Wild Edible Plants in the Campoo (Cantabria, Spain). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetin, J.; Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A.; Ricci, E.C.; Stranieri, S.; Banterle, A.; Perugini, M. The Biasing Effect of Evocative Attributes at the Implicit and Explicit Level: The Tradition Halo and the Industrial Horn in Food Products Evaluations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelto, G.H.; Pelto, P.J. Diet and Delocalization: Dietary Changes since 1750. Hunger Hist. 1985, 14, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokthi, E.; Kruja, D. Consumer Expectations for Geographical Origin: Eliciting Willingness to Pay (WTP) Using the Disconfirmation of Expectation Theory (EDT). J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bayón, S.; Fernández-Barcala, M.; González-Díaz, M. In Search of Agri-Food Quality for Wine: Is It Enough to Join a Geographical Indication? Agribusiness 2020, 36, 568–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigman-Grant, M.J. Food Choice: Balancing Benefits and Risks. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, D.R.; Knaapila, A. Genetics of Taste and Smell: Poisons and Pleasures; Bouchard, C., Ed.; 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc., 2010; Vol. 94.

- Almeida, A.T.M. dos S. Treino Do Paladar: Marcadores Precoces de Uma Alimentação Saudável Para a Vida., Universidade do Porto, 2010.

- Albuquerque, U.P. de A.; Nascimento, F.A.L.B. do; Lins Neto, E.M. de F.; Santoro, F.R.; Soldati, G.T.; Moura, J.M.B.; Jacob, M.C.M.; Medieros, P.M. de; Gonçalves, P.H.S.; Silva, R.H. da; et al. Breve Introdução à Etnobiologia Evolutiva; 1st ed.; Nupeea, 2020.

- Plasek, B.; Lakner, Z.; Kasza, G.; Temesi, Á. Consumer Evaluation of the Role of Functional Food Products in Disease Prevention and the Characteristics of Target Groups. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predieri, S.; Sinesio, F.; Monteleone, E.; Spinelli, S.; Cianciabella, M.; Daniele, G.M.; Dinnella, C.; Gasperi, F.; Endrizzi, I.; Torri, L.; et al. Gender, Age, Geographical Area, Food Neophobia and Their Relationships with the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet: New Insights from a Large Population Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torri, L.; Tuccillo, F.; Bonelli, S.; Piraino, S.; Leone, A. The Attitudes of Italian Consumers towards Jellyfish as Novel Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.; Greene, N.; Jimenez, M.; Calderon, A.; Diaz, Y.; Sheraton, M. The Effect of Wrapper Color on Candy Flavor Expectations and Perceptions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, D.M.; Santos, G.M.C. dos; Gomes, D.L.; Santos, É.M. da C.; Silva, R.R.V. da; Medeiros, P.M. de Does the Label ‘Unconventional Food Plant’ Influence Food Acceptance by Potential Consumers? A First Approach. Heliyon 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.H.; Moura, J.M.B.; Ferreira Júnior, W.S.; Nascimento, A.L.B.; Albuquerque, U.P. Previous Experiences and Regularity of Occurrence in Evolutionary Time Affect the Recall of Ancestral and Modern Diseases. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 8, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.M.C.; Barbosa, D.M.; Santos, É.M. da C.; Gomes, D.L.; Silva, R.R.; Medeiros, P.M. Experiências De Popularização De Plantas Alimentícias Não Convencionais No Estado De Alagoas, Brasil. Ethnoscientia 2020, 5, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Tuorila, H.; Hartmann, C. Consumer Responses to Novel and Unfamiliar Foods. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, R.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Product Appropriateness, Willingness to Try and Perceived Risks of Foods Containing Insect Protein Powder: A Survey of U. S. Consumers. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 3215–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogari, G.; Menozzi, D.; Mora, C. The Food Neophobia Scale and Young Adults’ Intention to Eat Insect Products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, B.; Capiola, A. Physiological Responses of Food Neophobics and Food Neophilics to Food and Non-Food Stimuli. Appetite 2012, 58, 1106–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Trijp, H.C.M.; van Kleef, E. Newness, Value and New Product Performance. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadán, A.; Bernabéu, R. A Systematic Review of Studies Using the Food Neophobia Scale: Conclusions from Thirty Years of Studies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.M.M. d.; Carvalho, F.M.; Pereira, R.G.F.A. Colour and Shape of Design Elements of the Packaging Labels Influence Consumer Expectations and Hedonic Judgments of Specialty Coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaud, D.A.; Melnyk, V. The Effect of Text-Only versus Text-and-Image Wine Labels on Liking, Taste and Purchase Intentions. The Mediating Role of Affective Fluency. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Rahman, I.; Geng-Qing Chi, C. Can Knowledge and Product Identity Shift Sensory Perceptions and Patronage Intentions? The Case of Genetically Modified Wines. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, M.B.S. Brazilian Açaí Berry and Non-Timber Forest Product Value Chains as Determinants of Development from a Global Perspective. 2018, 249.

- Medeiros, P.M. de; Barbosa, D.M.; Santos, G.M.C. dos; Silva, R.R.V. da Wild Food Plant Popularization and Biocultural Conservation: Challenges and Perspectives. In Local Food Plants of Brazil; Jacob, M.C.M., Albuquerque, U.P., Eds.; 2021; pp. 341–350 ISBN 978-3-030-69139-4.

- Svanberg, I.; Ståhlberg, S. Wild European Dewberry, Rubus Caesius L. (Fam. Rosaceae), in Sweden: From Traditional Regional Consumption to Exotic Dessert at the Nobel Prize Banquet. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.; Borelli, T.; Beltrame, D.M.O.; Oliveira, C.N.S.; Coradin, L.; Wasike, V.W.; Wasilwa, L.; Mwai, J.; Manjella, A.; Samarasinghe, G.W.L.; et al. The Potential of Neglected and Underutilized Species for Improving Diets and Nutrition. Planta 2019, 250, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, M.C.; McCarter, J.; Mead, A.; Berkes, F.; Stepp, J.R.; Peterson, D.; Tang, R. Defining Biocultural Approaches to Conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aai (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) - A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Assessment of the Species’ Health Claims. Phytochem. Lett. 2011, 4, 10–21. [CrossRef]

-

Suwardi, A.B.; Navia, Z.I.; Harmawan, T.; Syamsuardi; Mukhtar, E. Ethnobotany and Conservation of Indigenous Edible Fruit Plants in South Aceh, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 2020, 21, 1850–1860. [CrossRef]

- de Medeiros, P.M.; dos Santos, G.M.C.; Barbosa, D.M.; Gomes, L.C.A.; Santos, É.M. da C.; da Silva, R.R.V. Local Knowledge as a Tool for Prospecting Wild Food Plants: Experiences in Northeastern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Fenko, A.; Leufkens, J.M.; van Hoof, J.J. New Product, Familiar Taste: Effects of Slogans on Cognitive and Affective Responses to an Unknown Food Product among Food Neophobics and Neophilics. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).