1. Introduction

About 4.6 million adults live with some type of mental or physical disability in the United States [

1]. This entails any individual, adult or child, whose physical, intellectual, social, or emotional skills fall outside of what is considered normal regarding growth and development standards. These individuals are considered part of the vulnerable population as their disability can place limitations in their access to oral care and make it challenging to practice and maintain oral health [

2].

Many studies suggest that people with disabilities are more likely to have poor oral hygiene, periodontal diseases, and untreated dental caries compared to the general population [

2]. Review reports have shown that people with disabilities have compromised oral hygiene and higher plaque levels, more severe gingivitis and periodontitis, more untreated dental disease, and higher numbers of extracted teeth [

3]. The oral condition of people with special needs is also influenced by age, gender, family, socioeconomic status, and severity of impairment. All those challenges associated with disability may contribute to an increased risk of experiencing oral diseases. These include the presence of cognitive, physical, and behavioral limitations that make it difficult to perform daily oral care and cooperate during dental visits. Their routine medications also influence their overall oral health. Challenges of oral healthcare can be exacerbated with prevalence of high poverty rate among this population [

1]. Adults may be at even higher risk of developing oral diseases as they may lack access to dental care across the lifespan [

1]. Poor oral health among people with special needs also has a negative impact on digestion, nutrition, and speech which will gradually have a great impact on their overall quality of life. A reduction in oral health can lead to many burdensome consequences, while an improved oral health status can mitigate health, social, and economic aspects of their lives [

1].

Oral health maintenance is a particularly important issue for this vulnerable population that experience both poor oral health and a high level of unmet treatment needs. As in other health care areas, their oral health care is largely dependent on the knowledge, attitude, and practices of the individuals and their caregivers [

4]. The inability of individuals with intellectual disability to self-report their oral health problems further reduces the chances of any timely interventions [

4]. Due to deficiencies in communication skills of these individuals, their caregivers’ awareness and understanding of patients’ conditions are limited, resulting in the existing and ongoing diseases becoming more aggravated. Several federal reports have called attention to the disproportionate impact of oral disease on people with disabilities [

4]. In each report, lack of information about the complex issues involved in meeting the needs of this group was identified as a significant barrier to understanding and improve their oral health [

4].

Ascertaining oral health status in this vulnerable population has been largely conducted using self-administered questionnaires [

4]. For this study, we aim to use this method to gather information on oral health needs using the information collected from the clients at Helping Restore Ability (Arlington, TX) and Neuro Assistance Foundation (Keller, TX). This data will not only help serve them better, but also get a general understanding and assessment of oral health care needs for this underserved population. This work aims to generate supporting data that will help facilitate the changes needed to improve oral health in people with disabilities.

2. Materials and Methods

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval (IRB # 2022.0329) was obtained on April 7, 2022, to collect Oral Health Needs Assessment survey among people with special health care needs. The inclusion criteria for the study were people with upper extremities or related disorders in the age group of 18 to 65 including all ethnicity and genders. People under the age of 18 and people with cognitive disorders were excluded from the study. The online link to Qualtrics survey consisting of 13 questions was sent out to the clients at Helping Restore Ability and Neuro Assistance Foundation who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The survey was conducted from July 2022 till August 2022. 12 emails were sent to participants as a reminder to complete the survey. Additionally, the survey reminders were sent out to 750-800 clients via text.

Once participants electronically signed the consent form to participate in the study, which was the first question of the questionnaire, they were given access to the rest of the questions (Q2-Q13). Next, they provided their contact and demographic information. Then they answered the questions related to their oral health status and the tasks involved in practicing daily oral health. The questions are listed in

Table 1 and they were categorized based on the type of information that was gathered from each question, not necessarily in the same order of the questions in the survey.

In order to create ease and answer unresolved questions for survey participants, Frequently Ask questions (FAQ’s) and answers were created and google voice numbers were also included for direct help or questions. 185 participants responded to the survey and 95 out of those participants completed it. The data from the survey was extracted in Microsoft Excel file and analyzed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS. Univariate analyses were used to explore the frequencies for the dependent, independent, and demographic variables [

5]. The analysis conducted was descriptive statistics and univariate analysis. To calculate the percentage of the individuals who felt uncomfortable/or comfortable in performing any of the tasks listed in questions six through nine, the total number of participants who responded 1-3 (below neutral) and 5-7 (above neutral) were categorized as reported uncomfortable and comfortable, respectively.

3. Results

The results on demographic information (Q4 and Q5) showed that out of 128 total number of participants, more than half were female with the percentage of 71.88%, 26.56% were male, and 1.56% preferred not to say. Additionally, White people followed by African Americans accounted for the largest participants, 39% and 37%, respectively. The percentage dropped to 16% for Hispanic or Latino and 6% for Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1.5% responded other these results are consistent with the national data showing the same pattern of the population distribution [

6]. Generally, women were slightly more susceptible to having disabilities compared to men, partly due to their higher life expectancy [

6].

Table 2 summarizes the results related to questions (Q6-Q8) that investigated the barriers to maintain oral hygiene practices including difficulties in dental visits.

Questions six through eight investigated individuals’ comfort level in executing all activities required to maintain their oral healing (

Table 2). Questions six and seven focused on performing daily tasks involved in brushing, flossing, and rinsing. Question eight evaluated the overall barriers and discomfort to each activity such as brushing teeth, using mouthwash, and visiting dentists to maintain overall health by considering all tasks involved in each activity. The results collected from Q6 suggested that out of all survey participants about 33.68% were uncomfortable putting toothpaste on the toothbrush, 30.52% uncomfortable holding the toothbrush, 29.41% uncomfortable putting brush inside mouth, 33.69% uncomfortable moving brush inside the mouth, 26.32% uncomfortable taking the brush out, and 30.85% uncomfortable rinsing the mouth. Based on this outcome, most participants were the least comfortable putting the toothpaste on the brush (24.21%), and the most comfortable taking the brush out of their mouth (64.21%). The results obtained from question 7 showed 29.79 % were uncomfortable opening the water faucet, 29.48% mentioned that they were uncomfortable getting water in the mouth, 24.2% were uncomfortable spitting water, and 33.68% were uncomfortable closing the water faucet. Out of all responders the majority said closing the water faucet was the most difficult task (16.84%) and spitting the water out was the least difficult one (61.05%). The results of question eight indicated that about 30.34% of the responders were uncomfortable in brushing the teeth, 32.98% were uncomfortable using the mouthwash, 42.39% were uncomfortable asking for help when brushing their teeth, and 21.5% were uncomfortable about seeking the dental care. Results from this question indicated more than half of the responders were very comfortable seeking dental health care (59.14%); however, participants were the least comfortable asking for help from caregivers when brushing their teeth (28.26%). Overall, question six through eight highlight the need for better technologies to allow this population to perform daily dental hygiene practices for maintaining overall oral health independently.

This survey further assessed self-reported oral health status of these individuals (Q9-Q11) to maintain oral health. As displayed in

Figure 1.a, only a small percentage of participants (7%) scored 5 and above when they were asked how much pain they had in their teeth or gums on the scale of 1 (no pain) to 7 (very painful) (Q9). According to survey response to question ten (

Figure 1.b), 10.53% were Very Dissatisfied with their oral health, 11.58% were Not Satisfied, 23.16% were Neutral, 25.26% were Satisfied and 29.47% were Very Satisfied. It is apparent that over 20% of this population are not satisfied with their oral health and that may be even higher considering the people who answered neutral. The survey response to question 11 displayed in

Figure 1.c, showed 42.86% had cavities, 7.14% had been diagnosed with gum disease, 1.19% had oral cancer, 15.48% have been diagnosed with other, and 33.33% mentioned response as “they don’t know”. These data clearly indicate over 65% of the responders had some form of oral health issue.

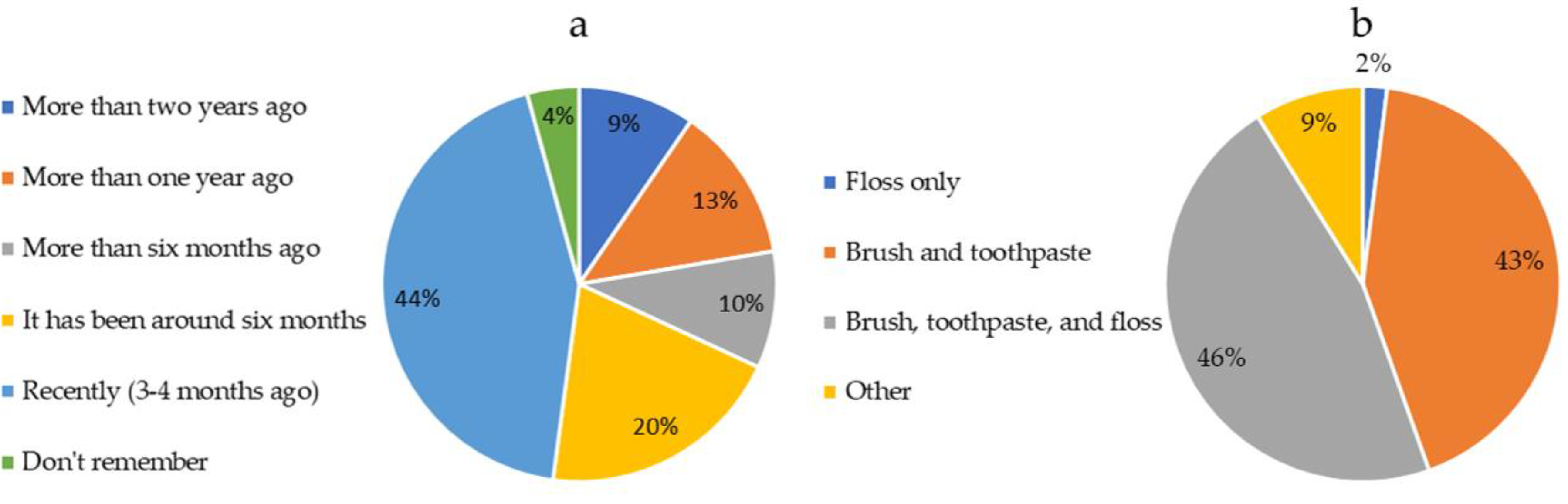

Questions 12 and 13 investigated the participants’ routines such as the frequency of visiting a dentist and the method of practicing oral hygiene. When participants were asked how long it had been since their last visit to a dentist or dental hygienist (Q12), responses revealed that 43.62% had been seen a clinician recently (3-4 months), 20.21% had dental visits about six months ago. 9.5% of participants had been seen for more than 6 months but less than 1 year ago. Among responders 12.77% and 9.75% had not been seen by a clinician in over one and two years, respectively, and 4.26% could not remember (

Figure 2.a). Considering 6 months as the recommended frequency of visiting a dentist or a dental care hygienist, over 30% of the respondents had not followed general dental care guidelines. Among the participants who provided information about their method of practicing dental hygiene (

Figure 2.b), 42.57% reported using brush and toothpaste, and floss, 46.53% reported using brush and toothpaste, 1.98% reported using floss only, while 8.91% reported using other methods. Although the result indicated that most participants (89%) did used the major methods (brush, toothpaste, and floss and/or brush and toothpaste) to maintain their oral health, the rate of developing oral diseases remains higher in these individuals. This may be due to their limitations in properly executing daily oral hygiene tasks involved in brushing and flossing. This is another evidence that there is a need for advancement in technologies to help this underserved population improve their oral health.

4. Discussion

This study is one of the significant cross-sectional surveys focusing on the self-reported oral health status and barriers faced by individuals with disabilities in maintaining their daily oral health. The aim of this research was to assess the needs of these individuals and identify areas for improvement in their oral health care. The results of the study indicate that 45.27% of people with disabilities are not satisfied with their oral health, and 30% of them do not visit dental care professionals at the recommended frequency of every six months [

1]. Additionally, there is a higher prevalence rate (65%) of oral diseases in this population compared to the general population [

1]. These satisfaction and prevalence rate data clearly demonstrate a gap in dental care for individuals with disabilities.

Regarding the overall brushing activity, data clearly indicate both hand and arm dexterity limitations affect their ability to perform toothbrushing. Participants reporting difficulties in an average of over 30% for each task involved in toothbrushing. However, results also highlight that a large percentage of these individuals (42%) are reluctant to ask for help from their caregivers for toothbrushing activities. These observations emphasize that there is a need for advancements in toothbrush technology to minimize the difficulties in handling and the reliance on upper extremity movements. Data also supports that technology needs to be improved for them to be self-sufficient in supporting activities to brushing and flossing such as opening and closing the faucet.

An important limitation of this study is the use of the cross-sectional study design, which restricted the establishment of temporality between the independent variables [

7]. This study is limited to the descriptive analysis of the data and does not identify possible risk factors. It will be important to understand the range of motion of the participant in performing a complex task such the teeth brushing and oral hygiene maintenance. We suggest using the clinical trial to complete a study that evaluates functional deficiencies and their relation to oral health. Another limitation is the low response rate to oral health surveys. The survey response rate is low which is aligned with the general response rate in this population. For future studies, we suggest including some incentive for survey completion which can increase the response rate.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research sheds light on the oral health needs of individuals with disabilities, a vulnerable population facing significant challenges in accessing and maintaining oral care. The findings emphasize how factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and severity of impairment influence the oral condition of individuals with special needs. Caregivers play a crucial role in ensuring oral health maintenance for these individuals due to their limitations in self-reporting oral health problems. The study also underscores the importance of addressing disparities and barriers faced by people with disabilities in accessing dental care, particularly among adults who may lack dental care throughout their lives. By utilizing self-administered questionnaires and data from organizations like Helping Restore Ability and Neuro Assistance Foundation, this study provides valuable insights into the oral health care needs of an underserved population. The results advocate for targeted interventions, increased caregiver awareness, and systemic changes to improve oral health outcomes for people with disabilities, thereby reducing the health, social, and economic burdens associated with poor oral health and enhancing their overall well-being.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, G.S.S, A.N, and M.W and ; methodology, G.S.S; software, G.S.S.; validation, G.S.S, A.N, and M.W; formal analysis, G.S.S.; investigation, G.S.S.; resources, G.S.S, M.W.; data curation, G.S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.S.; writing—review and editing, G.S.S, A.N.; visualization, G.S.S.; supervision, M.W.; project administration, G.S.S.;.

Funding

This research received funding from the Helping Restore Ability.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate support from Vicki Niedermayer, Chief Executive Officer at Helping Restore Ability, for providing necessary support to the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

PI

Aida Nasirian: Department: Research Institute IRB Protocol #: 2022-0329; Study Title: Oral Health Needs Assessment in Population with Special Health Care Needs; Effective Approval: 4/7/2022; The IRB has approved the above referenced protocol in accordance with applicable regulations and/or UTA’s IRB Standard Operating Procedures.

References

- J. P. Morgan et al., "The oral health status of 4,732 adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities," The Journal of the American Dental Association, vol. 143, no. 8, pp. 838-846, 2012.

- Suresh S, Indiran MA, Doraikannan S, Prabakar J, Balakrishnan S. Assessment of oral health status among intellectually and physically disabled population in Chennai. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 Feb;11(2):526-530. Epub 2022 Feb 16. PMCID: PMC8963658. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Poyato-Ferrera, J. J. Segura-Egea, and P. Bullón-Fernández, "Comparison of modified Bass technique with normal toothbrushing practices for efficacy in supragingival plaque removal," (in eng), Int J Dent Hyg, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 110-4, May 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Kim, J. B. Park, W. C. Lee, Y. J. Kim, and Y. Lee, "Differences in the oral health status and oral hygiene practices according to the extent of post-stroke sequelae," Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 476-484, 2018/06/01 2018. [CrossRef]

- Shelke, G.S.; Marwaha, R.; Shah, P.; Challa, S.N. Impact of Prenatal Health Conditions and Health Behaviors in Pregnant Women on Infant Birth Defects in the United States Using CDC-PRAMS 2018 Survey. Pediatr. Rep. 2023, 15, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treaster DE, Burr D. Gender differences in prevalence of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Ergonomics. 2004 Apr 15;47(5):495-526. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelke, G.S.; Marwaha, R.S.; Shah, P.; Challa, S. Role of Patient’s Ethnicity in Seeking Preventive Dental Services at the Community Health Centers of South-Central Texas: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).