1. Introduction

The care of a child with cancer involves several physical and psychological constraints that can be perceived as “aggression” by the child and his family. The latter can have negative reactions such as non-adherence to treatment or even a depressed mood and aggressive behavior with the medical staff [

1]. Among the non-pharmacological measures used to help the child and his family to better cope with this situation of extreme stress, music therapy (MT) has shown its evidence in improving the quality of life of children with cancer [

2].

According to the French Federation of Music Therapy, MT is "a practice of care, counseling, accompaniment, support or rehabilitation, using sound and music, in all their forms, as a means of expression, communication, structuring and analysis of the relationship” [

3]. It is said to be “active” when it favors sound and musical production, improvisation and creativity and “receptive” when it is based more on listening. Since the first use of MT in the 1970s, this process has occupied an increasingly important place, all over the world, in the psychological and therapeutic care of patients with serious pathologies. To our knowledge, there is no tunisian publication on MT and its effects in children with cancer.The aim of our study was to mainly evaluate the impact of MT on quality of life of children hospitalized with pediatric cancers and secondarily to investigate its effect on cardiac and respiratory parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a quasi-experimental study (before-after type) comparing the patient before and after MT sessions from April 1st to August 31st 2021 at the pediatric oncology unit in Bechir Hamza Children's Hospital in Tunis. All patients aged 2 to 14 years old who were hospitalized during the study period were included. Children with deafness, profound encephalopathy or impaired consciousness were not included. Children who died during the study period were excluded.

After adequate and complete information, free and informed consent was obtained from the parents. Prior approval from the ethics committee of Bechir Hamza Children's hospital was given before the start of the trial.

First, PedsQL Module Cancer questionnaire french version 3.0 [

4] was translated into tunisian dialect and then was filled out by the child and/or his parent. The questionnaire is composed of 27 items divided into eight dimensions: pain, nausea, anxiety related to medical procedures, anxiety related to treatments, worry, cognitive disorders, perception of physical appearance and communication. For each item, the respondent answered questions then the values assigned to the different items were transformed into a score. The overall score corresponded to the average value of the eight scores obtained. The higher the score, the better the quality of life.

Second, the patient participated in four MT sessions once a week for about 20 minutes each. The type of MT (active or passive) was decided according to the child’s preferences in agreement with the music therapist. The sessions were conducted with the same music therapist in a newly designed MT workshop for the department. Child's respiratory rate (RR) and heart rate (HR) were recorded on study sheets by a physician, not involved in the study, before and at the end of each MT session. The patient was at rest for 15 minutes before measuring the cardiorespiratory parameters.

Third, the same questionnaire was filled out by the patient or his parent after the four MT sessions. Data collection was done using two informative sheets. The first sheet, completed by a doctor not part of the medical team, focused mainly on the socio-demographic and clinical data of the patient. The second sheet was filled out by the music therapist who specified the type of MT, the scale played and the instruments used.

SPSS Statistics version 23.0 software was used for data entry and analysis. Qualitative variables were expressed in terms of proportions. Quantitative variables were described in terms of means, medians and standard deviations. We used non-parametric tests such as the Wilcoxon ranking test to compare medians, the Mann-Whitney test to compare means and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to verify the normality of the distribution. The significance threshold (p value) was set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic data

We included 20 patients with a sex ratio of 1/1. The average age was 7 ± 4,5 years [2-14]. Among the children included in the study, 15 had at least one sibling. Eight patients were in school during the study period.

No patient was excluded during the study.

3.2. Disease data

The cancers collected in our study were hematological malignancies in three cases and solid tumors in 17 cases. Cancer was metastatic in 14 patients.

The majority of children were undergoing treatment (16/20), two were in relapse, one patient was newly diagnosed and one was on palliative treatment.

The patients had been cared for in the unit for more than six months were nine (9/20).

The majority of children were admitted for chemotherapy treatment (12/20), six were admitted for febrile aplasia (6/20) and two for acute fever (2/20).

3.3. Music therapy data

The first three sessions were receptive while the last ones were both receptive and active. The scales played were more or less balanced between the participants during sessions one, two and four, while for the third session, the most played scales were minor and mixed. Different instruments were used (shaker, kalimba, piano, guitar, maraca, ukulele...) but the most frequently used one was the guitar (

Table 1).

3.4. Assessment of patient’s quality of life

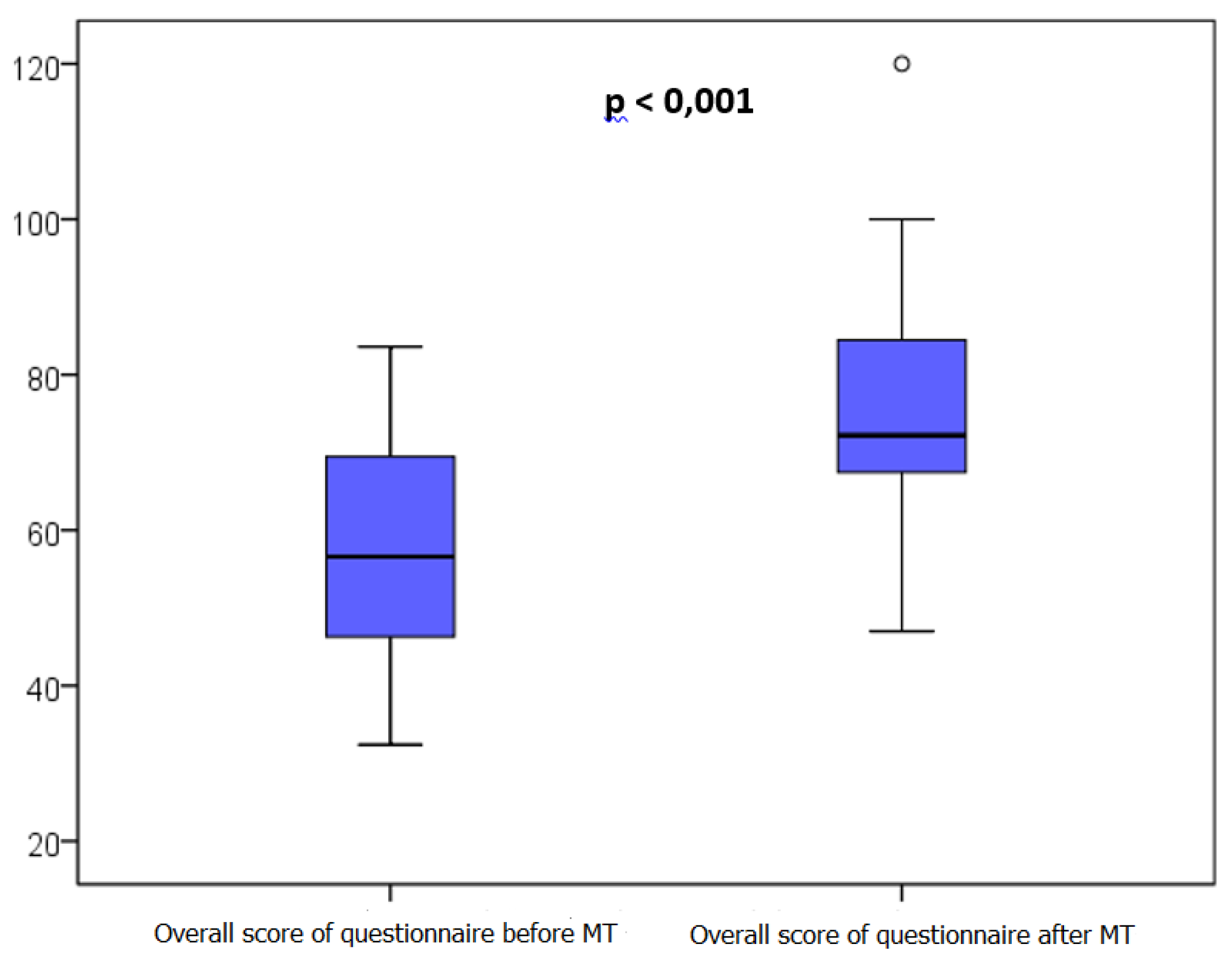

The questionnaire was filled out in 13 cases by one of the parents and in seven cases by the child himself. The median value of the total score increased significantly by 21.6% (p < 10

-3) from 57 [46 - 70] before MT to 72 [67 -85] after four sessions (

Figure 1). We also noted a significant decrease in scores of pain (p = 0,02), nausea (p = 0,009), anxiety related to medical procedures (p = 0,009) and treatments (p = 0,03) as well as concerns about the future (p = 0,005). Furthermore, we reported a significant improvement in child's physical perception (p = 0,01), as well as in communication between the patient and his family members and medical staff (p = 0,005) (

Table 2). However, there was no significant improvement in cognitive disorder (p = not significant (NS)).

3.5. Analytical study

We noted a significant improvement in the total score in both sexes (

Table 3). Boys had less nausea (p = 0,03), less anxiety related to medical procedures (p = 0,008), less worry (p = 0,02) and a better physical perception (p = 0,03) after four sessions of MT. For girls, the overall quality of life also improved significantly after the MT sessions (p = 0,03) but their response seemed less significant than that of the boys (

Table 3). On the other hand, communication has frankly improved (p = 0,03) for girls unlike the boys (p = NS). Using the Mann-Whitney U test of independent samples, we found a significant difference in the worry score between boys and girls: boys were less worried than girls after the MT sessions (p = 0,02).

Looking at different age groups, the two groups that responded best to MT were those aged between two and four years old (p = 0,03) and those aged between eight and 14 years old (p = 0,02) (

Table 3). Anxiety decreased for these two groups but more significantly for the group aged eight to 14 years (p = 0,02). The worry score increased significantly in the two- to four-year-old group only (p = 0,04). Using the Kruskal-Wallis test of independent samples, we did not find statistically significant difference between age groups regarding the different scores on the questionnaire after MT.

Taking into account the family situation, children with siblings responded better to MT than children without siblings (

Table 3). The scores for nausea (p = 0,01), anxiety related to medical procedures (p = 0,02) and treatments (p = 0,03) , worry (p = 0,008) and communication (p = 0,009) were significantly increased in the sibling group. Using the Mann-Whitney U test of independent samples, we found a statistically significant difference between children with siblings and children without siblings regarding the total questionnaire score (p = 0,005), the anxiety related to medical procedures (p = 0,008), the anxiety score related to treatment (p = 0,03) and the communication with the medical staff (p < 10

-3).

By focusing on schooling, our study showed that schooled children were less sensitive to the effects of MT than non-schooled children (

Table 3). Indeed, we observed after the four MT sessions that non-schooled children had a better quality of life (p = 0,003), a reduction in pain (p = 0,03) and worry about the future (p = 0,01), a better self-esteem regarding their physical appearance (p = 0,008), and better communication with their family and medical staff (p = 0,01). Using the Kruskal-Wallis test of independent samples, we did not find a significant difference between children according to their school status.

On the other hand, our study demonstrated that patients with metastatic tumors had a better response to MT (

Table 3) with a significant increase in overall quality of life scores (p = 0,003) as well as communication (p = 0,003), and a significant decrease of nausea (p = 0,002), treatment-related anxiety (p = 0,03) and worry (p = 0,03). For children with a localized tumour, the improvement was notable for anxiety related to medical procedures (p = 0,04). Nevertheless, we did not find a statistically significant difference between the two groups according to the Mann-Whitney U test of independent samples.

Whatever the duration of care within the service, the quality of life of the participants improved after four MT sessions, but the children treated recently (less than six months) seemed to respond better to MT (

Table 3). According to the Mann-Whitney U test of independent samples, children who had been in care for less than six months developed a better self-esteem of compared to others (p = 0.02).

3.6. Evaluation of cardiorespiratory parameters

We observed a significant decrease in RR and HR in all participants after each MT session (

Table 4). According to the Mann-Whitney U test of independent samples, these parameters were not affected by gender, age, education, siblings, stage of disease and the duration of care.

Our study demonstrated a significant improvement in quality of life of children with cancer after MT, which has already been reported by several authors. Thus, a recent meta-analysis reported eleven articles including 429 children aged between 0 and 18 years [

2]. The analysis of five articles showed that music influenced positively quality of life of children compared to the control group with a standardized mean difference (SMD) of -0.80 (95% confidence interval: 1.17-0.43).

Our results also suggested that pain experienced by children decreased significantly after MT. A randomized clinical trial [

5] was carried out in 40 children aged seven to 12 years with leukemia, and compared the intensity of pain induced by a lumbar puncture between two groups: a control group (n=20) and a group having MT (n=20). Anxiety scores were measured before and after the procedure. The results showed lower pain scores, lower heart and respiratory rates in the music group during and after the lumbar puncture. Anxiety scores were also lower in the music group before and after the procedure. The authors conclude that MT is a reliable, inexpensive means of distraction that reduced the level of anxiety in children with cancer before invasive procedures and that it also reduces the intensity of pain at the time of the procedure.

These results were supported by those of Da Silva Santa's meta-analysis [

2], which demonstrated that MT had a positive impact on anxiety and pain in the group of patients who had MT sessions compared to the control group. Dobeck and al. [

6] attempted to analyze the effects of MT on the central nervous system using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. They proved that emotions provoked by music affected the neuronal activity of the brainstem and the spinal cord and that the intensity of pain decreased significantly when MT was performed concomitantly with the painful stimuli.

It was demonstrated in our study that the level of anxiety decreased significantly after four sessions of MT, which has been reported in various studies, particularly in adults. In fact, a meta-analysis published in Cochrane included 81 trials with 5567 participants including 5306 adults and 270 children [

7]. MT has been shown in these trials to reduce anxiety in adults with cancer, with an average reduction of 7.73 units (95% confidence interval -10.02 to -5,44) according to “Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory scale”. The results also suggested a positive impact of MT on depression in adults (SMD: -0.41, 95% CI -0.67 to -0.15).

Our results also showed the effectiveness of MT on self-esteem, which has already been reported by a multicenter study conducted in Northern Ireland by Porter and al. [

8] including 251 children aged eight to 16 years followed for social, behavioral and emotional difficulties. They were divided into two groups, one group receiving 12 weekly MT sessions and another group receiving usual care. The evaluation at the 13th week showed a significant decrease in depressive symptoms and a marked improvement in self-esteem in the group with MT as well as an improvement in communication assessed by the “Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scales” only for children over 13 years old (p=0.007). In fact, the child affected by cancer sees his body metamorphose more or less rapidly, hence a potential risk of damage to self-esteem, particularly among adolescents. MT could therefore be a good alternative to improve self-perception and communication with people around children. An American multicenter randomized control trial [

9] studied the impact of MT on the social behavior of 83 children with cancer aged four to seven years by comparing a group treated by MT (n=27) versus a group listening to music (n=28) and another group listening to audio storybooks (n=28). The results reported were that MT improved facial expressions, enhanced active engagement in social relationships (p < 0.0001) as well as social interactivity (p < 0.05). These positive repercussions would facilitate communication with family and medical staff, especially among adolescents with cancer who tend to isolate themselves from the rest of the world.

Although our study did not demonstrate an efficacy of MT in improving cognitive impairment, several studies have demonstrated the opposite. In fact, a meta-analysis [

10] on the impact of MT in the treatment of schizophrenia, published in 2017 and including 18 studies with a total of 1215 participants, highlighted the short, medium and long-term beneficial effects of MT on the behavior of schizophrenic patients. The data analyzed found positive effects of MT on the quality of life and social functioning of patients who received MT compared to the control group [

10]. Regular music listening reduced auditory hallucinations in these patients and improved their quality of life. The positive effect of music on the brain in schizophrenia has also been demonstrated by functional magnetic resonance imaging [

10]. Similarly, a Chinese study published in 2018 revealed a decrease in the incidence of psychiatric disorders in adults with dementia and Alzheimer's disease [

11].

Nikjeh and al. [

12] found that musicians trained in MT performed better than those who were not trained in MT. This could represent one of the strong points of our study where all the sessions were provided by a trained music therapist.

The effects of MT on the cardiorespiratory parameters demonstrated in our study have also been reported by other authors. Uggla and al. [

13] conducted a randomized control trial on 24 children who had a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. They observed a significant drop in lasting heart rate for four to eight hours after the intervention with no effect on the respiratory rate and oxygen saturation. Uggla also reported in the Lancet the positive experiences of children who have been confronted with MT with a particular impact on well-being and self-confidence [

14]. In another study of 115 adult patients [

15] for whom music was played in the operating room, we compared the vital parameters measured in the waiting room without music with those measured in the operating room with music. Mean arterial pressure, HR and RR were significantly lower in the operating room (p<0.0001).

A systematic review of the literature [

16] showed that listening to music stimulated the parasympathetic tone of the cardiovascular system.

Among the strengths of our study, we cite its innovative nature, highlighting a technique that is still little known in Tunisia but which has already proven its worth in developed contries in improving the daily lives of children with cancer. This is the first study of its kind in North Africa. It is a quasi-experimental study in which the patient is his own control, thus avoiding the bias of interindividual variability. We highlight also the presence of a trained music therapist.

Among the weak points, we report the small number of participants and the absence of a control group which could have increased the power of the study and the relevance of the results. By comparing the same patient before and after the intervention, we may have introduced measurement and subjectivity bias because the child may have been enthusiastic about the idea of participating in the different MT sessions, thus making his judgment more subjective. The PedsQL questionnaire was translated into tunisian dialect by a tunisian doctor, a version which should be followed by a back-translation procedure in order to have the best cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire and lead to a validated translation equivalent to the original version.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed a positive impact of MT on quality of life of children affected by cancer with a reduction in anxiety and stress symptoms. These results suggest the importance of integrating MT into daily practice in pediatric oncology. However, randomized double-blind studies with larger samples are needed to confirm these results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F. and M.W.H.; methodology, F.F. and M.W.H; validation, F.F.; formal analysis, H.B. and M.W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, F.F. and M.W.H.; writing—review and editing, F.F. and M.W.H.; visualization, F.F.; supervision, F.F.; project administration, F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Local Ethics Committee of BECHIR HAMZA CHILDREN’s HOSPITAL (protocol code 11/2021 and date of approval 05/05/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all the subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge: « Selima » Association in the person of Mrs. Fatma Chok and Mr Issam Magouri for the design and the realization of the project "Music in the hospital". German Embassy in Tunisia in the person of his Excellency Mr. Peter Prügel for the financing of the project: development of a music therapy workshop, equipment of the workshop with sophisticated computer equipment and various musical instruments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Rivas Molina NS, Mireles Pérez EO, Soto Padilla JM, González Reyes NA, Barajas Serrano TL, Barrera De León JC. Depression in school children and adolescents carriers of acute leukemia during the treatment phase. Gac Med Mex. 2015, 151(2), 186–191.

- Da Silva Santa IN, Schveitzer MC, Dos Santos MM, Ghelman R, Filho VO. Music interventions in pediatric oncology: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2021, 59, 102725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French Federation of Music Therapy. Who is he ? [On line]. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 21]. Available at: Available at: https://www.musicotherapie-federationfrancaise.com/musicotherapeute/.

- Mapi Research Trust. Pediatric quality of life inventory™ cancer module (pedsql™ cancer module) [Online]. 2022 [cited 2022 Aug 21]. Available at: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/pediatric-quality-of-life-inventory-cancer-module.

- Nguyen TN, Nilsson S, Hellström AL, Bengtson A. Music therapy to reduce pain and anxiety in children with cancer undergoing lumbar puncture: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010, 27(3), 146–155. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobek CE, Beynon ME, Bosma RL, Stroman PW. Music modulation of pain perception and pain-related activity in the brain, brain stem, and spinal cord: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Pain. 2014, 15(10), 1057–1068. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradt J, Dileo C, Grocke D, Magill L. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. In: The Cochrane Collaboration, éditeur. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. p. CD006911.pub2.

- Porter S, McConnell T, McLaughlin K, Lynn F, Cardwell C, Braiden HJ, et al. Music therapy for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: a randomised controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017, 58(5), 586–594. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robb SL, Clair AA, Watanabe M, Monahan PO, Azzouz F, Stouffer JW, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the active music engagement (AME) intervention on children with cancer. Psychooncology 2018, 17(1), 699–708.

- Witusik A, Pietras T. Music therapy as a complementary form of therapy for mental disorders. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2019, 47(282), 240–243.

- Lyu J, Zhang J, Mu H, Li W, Champ M, Xiong Q, et al. The effects of music therapy on cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 64(4), 1347–1358. [CrossRef]

- Nikjeh DA, Lister JJ, Frisch SA. Preattentive cortical-evoked responses to pure tones, harmonic tones, and speech: influence of music training. Ear Hear. 2009, 30(4), 432–446. [CrossRef]

- Uggla L, Bonde L, Svahn B, Remberger M, Wrangsjö B, Gustafsson B. Music therapy can lower the heart rates of severely sick children. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105(10), 1225–1230. [CrossRef]

- Uggla, L. Music therapy for children undergoing transplantation. Lancet Haematol 2021, 8(3), e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara JG, Ruszkowski JM, Worak SR. The effect of live classical piano music on the vital signs of patients undergoing ophthalmic surgery. Medscape J Med. 2008, 10(6), 149.

- Barbosa NC, De Paula BK, Azevedo GP, Teixeira AA, Barbaresco GL. Effectiveness of music therapy in reducing anxiety in cancer patients: a systematic review. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2019, 65(4), e08592.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).