1. Introduction

At the start of 2020, news emerged of an as-then unknown disease found in China. It was only one of many news stories worldwide in January 2020, but global media coverage soon became dominated by a single word: COVID-19. Sometimes a single word defines an era (Merriam-Webster, 2021), and indeed, this word has done so. After several weeks, the situation had significantly worsened as was considered an emergency, leading to the generally restricted movement, closures of public spaces, schools and universities. Correspondingly, the pace of production and consumption of media coverage on COVID-19 rapidly increased through the early months of 2020; e.g., Zafri et al., (2021) as the world began to make sense of and comprehend the scale and severity of what was happening.

The classification of COVID-19 by the World Health Organisation from a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” to a “Pandemic” took a little over one month (WHO, 2020). In this time, nations began responding differently; for instance, while Italy imposed stringent restrictions on people’s lives, Sweden followed a relaxed protocol (Bertone et al., 2020). There was a lag in individual responses that were shown to be strongly related to the number of early deaths (Bertone et al., 2020), and gradual as people slowly reduced their social mobility (Milani, 2021).

The spread of the disease across continents was widely reported, with a great majority of media outlets dedicating sections of their publications to this emerging global disease and its subsequent developments. Social media and internet news were conduits for updating, narrating and critiquing COVID-19 news, stories and claims etc., playing a vital role in disseminating public health information while capturing the changing attitudes and impact of COVID-19 as it raged across the globe.

In psychological research, recent work demonstrated a strong correlation between larger negative emotion vocabularies and psychological distress. Vine et al’s (2020) argument rests on abstract conceptions of vocabulary use as they codified words ostensibly relating to positive and negative emotion taken from public blogs and undergraduate essays. While this is useful at broadly explicating the link between vocabulary and psychological state, our analysis further elucidates this relationship in concrete terms by mapping vocabulary use during the first few months of the pandemic. In this current context of COVID-19, studies are beginning to emerge that have explored how vocabulary changes might add greater clarity and improve adherence to government directives (Sørensen et al., 2021). Also, online news media usually provide cross-continental examples due to the nature of the pandemic. Given that “emotion talk, concepts, and scripts may differ across cultures” (Dewaele & Pavlenko, 2002, p.264), these news items could show various cultural views on the pandemic across countries, especially the first responses of the governments (Yan et al., 2021).

We henceforth discuss and document the representation of media articles related to COVID-19 and trace how this speaks to the social power of language and its relationship with social change. The present study analyses the types of vocabulary shared and disseminated by such online news media during the early three months of the pandemic. It was a significant moment in the pandemic timeline where most countries were in denial, confused or shocked, and this instability is indicated in the vocabulary used by media. In particular, many new words and phrases were coined (e.g., ‘social distancing’) during the earlier months of the pandemic (Piekkari et al., 2021). We, therefore, make sense of the uncertainty, confusion and fear as the pandemic began to investigate the production of discourse and how the pandemic was framed and transformed in the media in those early months (February – April 2020). In doing this, we add evidence to the growing body of work that maps and/or recommends vocabulary changes.

2. Concepts and Definitions

2.1. Social Power of Language

Language analysis has long been recognised across many fields and disciplines to understand and describe changes in society and culture. Empirical work has documented how individuals understand and produce culture and society through language use, and indeed, how behaviour that does not conform with cultural expectations is challenged (e.g., Joyce et al, 2021). Similarly, socially informative research has shone a light on matters of environmental coverage (Amiraslani and Dragovich, 2021a; 2021b) to tease out how matters of water crises and wildlife management get represented in the discourse; for example, what the content of the newspaper’s message does and thus what recommendations. Understanding and scrutinising the use of language thus affords the opportunity to make recommendations, grounded in evidence, that can improve communication strategies and encourage individuals to change their behaviour. Manifestations of new lexicons considering emergent social events might then be tackled by understanding the broader representation and themes of the event and how that representation targets and speaks to social change in the making.

Fairclough (1992) directly correlates changes in the discourse with social and cultural change – illustrating his point via three tendencies of discourse change: commodification, democratisation, and technologisation. In Fairclough’s book, he argues for a three-dimensional framework of discourse analysis, which, put simply, regards the analysis of the text itself, the manner of production and interpretation, and the social practice, which are the circumstances that shape the nature of the production and interpretation. The global situation of COVID-19 provides a perspicuous opportunity to view, in a very short time, the relationship between the discourse and social upheaval vis-à-vis change in the making. Indeed, a recent example of such work by Tracy (2016) mapped marriage equality debates in the US to exemplify the discursive strategies and rhetorical devices employed that achieve social change. Tracy shines a light on how seemingly insignificant aspects of speech and writing (e.g., use of scare quotes, extreme case formulations, reported speech, storytelling etc.) shape and are shaped by the achievement of social change. Our present work follows a similar thread to track vocabulary use and identify patterns in the wider discourse relating to the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Speciality of the 21st Century and the Pandemic

Human-induced disasters and hazards have exposed all life on earth, including human, to more dangerous situations. The concept of ‘human-induced (i.e., anthropogenic, man-made, or human-induced) hazards’ are defined as those “induced entirely or predominantly by human activities and choices” (UNISDR, 2015, p.13). Since the start of the twenty-first century, the world has been embroiled in the stormy waves of human-induced disasters, notably the 9/11 tragedy and the consequent US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Arab Spring unrest across several countries in the Middle East region, and the terrorist wars in Syria and Iraq. Many other events have also destroyed infrastructure, killed people and wildlife due to the failures of human technologies, e.g., the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (in 2011, Japan) and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (in 2010, USA). Disasters fuelled by human-induced climate change have ruined infrastructure to the ash and killed people and wildlife, e.g., Megafires across the continents (in 2020). Various pandemics have also affected populations, e.g., the Western African Ebola virus epidemic (2013–2016) and the SARS pandemic (2002–2004). Interestingly, however, with the growing frequency and diversity of disasters, disaster risk science has been evolved with its related vocabularies, terms, definitions, and interpretations (Kelman, 2018). Such additionality highlights the critical role of vocabularies in communications and knowledge-sharing.

Another devastating event that has impacted our lives since late 2019 is the COVID-19 Pandemic (Hereafter, the pandemic). There is no doubt that the outbreak and spread of the pandemic have become one of the most destructive calamities that has affected the world in every aspect (Yan et al., 2021; Serikbayeva et al., 2020).

Numerous pandemics have occurred in the recorded history of humans, but this time, the situation has become more precarious and made us more vulnerable. Human settlements have become more densely populated, natural landscapes have been degraded, population growth has exerted more pressures on the limited resources, more intrusions of humans into wildlife territories has occurred, etc. At no point in the previous centuries, the number of urban residents had exceeded the number of rural ones, as has happened since 2007 (Ritchie and Roser, 2021). Land degradation, poverty and dysfunctional rural economies have subjected humans to illegal wildlife trades, among other activities.

Nevertheless, our understanding of the consequences and nuanced ripple effects is far more advanced, and we more closely monitor and document the multi-dimensional and devastating ramifications of the pandemic. The trade-off for understanding these dire consequences is that we have not seen such an improvement in the dissemination scale, diversity and speed of telecommunication technologies, notably the internet. We had not attempted such large-scale vaccination programmes in any country before. We had not observed such a wide range of cross-continental humanitarian aids, while most governments’ interventions and citizens have been unprecedented and unequal so far (Clark et al., 2020; Serikbayeva et al., 2020).

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Dataset

The first author identified the title of each news in English across various international online news platforms and selected those news items with any title encompassing the notion of COVID-19 (coronavirus, COVID, COVID-19, the Pandemic). Our news platforms were not selected based on any certain criteria or the origin country rather they included all online news platforms, and sources broadcasting in English. The timeframe restriction was made for the research as we considered the first three months of the outbreak (February-April 2020) (

Figure 1). This 3-month timeframe was deemed to be crucial for collating words. It covered the time (February) when the disease was renamed COVID-19 and the time (2nd April) when the number exceeded 1 million for the first time globally. Also, in the middle of this timeframe, the disease was finally declared as ‘the Pandemic’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 (WHO, 2020). Therefore, such a global shock influences the tone, scope and style of news writing and speeches.

3.2. Word Clustering

After the screening process, we read the news items in full and words were selected with no imposed criteria. Our earlier digital dataset consisted of a spreadsheet with over several hundreds of extracted English words. Nevertheless, there were overlapping and repetition amongst these entries which were removed. We screened the initial pool and retained 172 words (

Table 1). Selected words were classified manually according to their functions and implications into eight thematised groups. Lexical items were coded based on their semantic meaning at the word and sentential level. We drew from these meanings its relationship with larger units of discourse related to COVID-19. We considered the definition of function as ‘the action for which a person or thing is specially fitted or used or for which a thing exists’ (MW-Function, 2021). For example, we named a specific vocabulary class under the ‘Medical’ function. The implication was defined here as a ‘close connection’ (MW-Implication, 2021). For instance, vocabularies such as glove, cough, drug had a medical connection to each other. None of the words has been mentioned in more than one class while sorted alphabetically in each class. This study does not examine the appropriacy of word usage, their syntactic function, or their morphology.

4. Result

Table 1 presents selected words and eight arbitrary classes developed for this research.

Our eight vocabulary classes, collated during the first three months of the Pandemic, are embedded with different functions and implications. Indeed, our ‘status’ class include words that exceptionally describes characteristics of an actual situation during any pandemic. Not all classes encompass a large number of vocabularies, and only a few classes show higher numbers of words and terms (

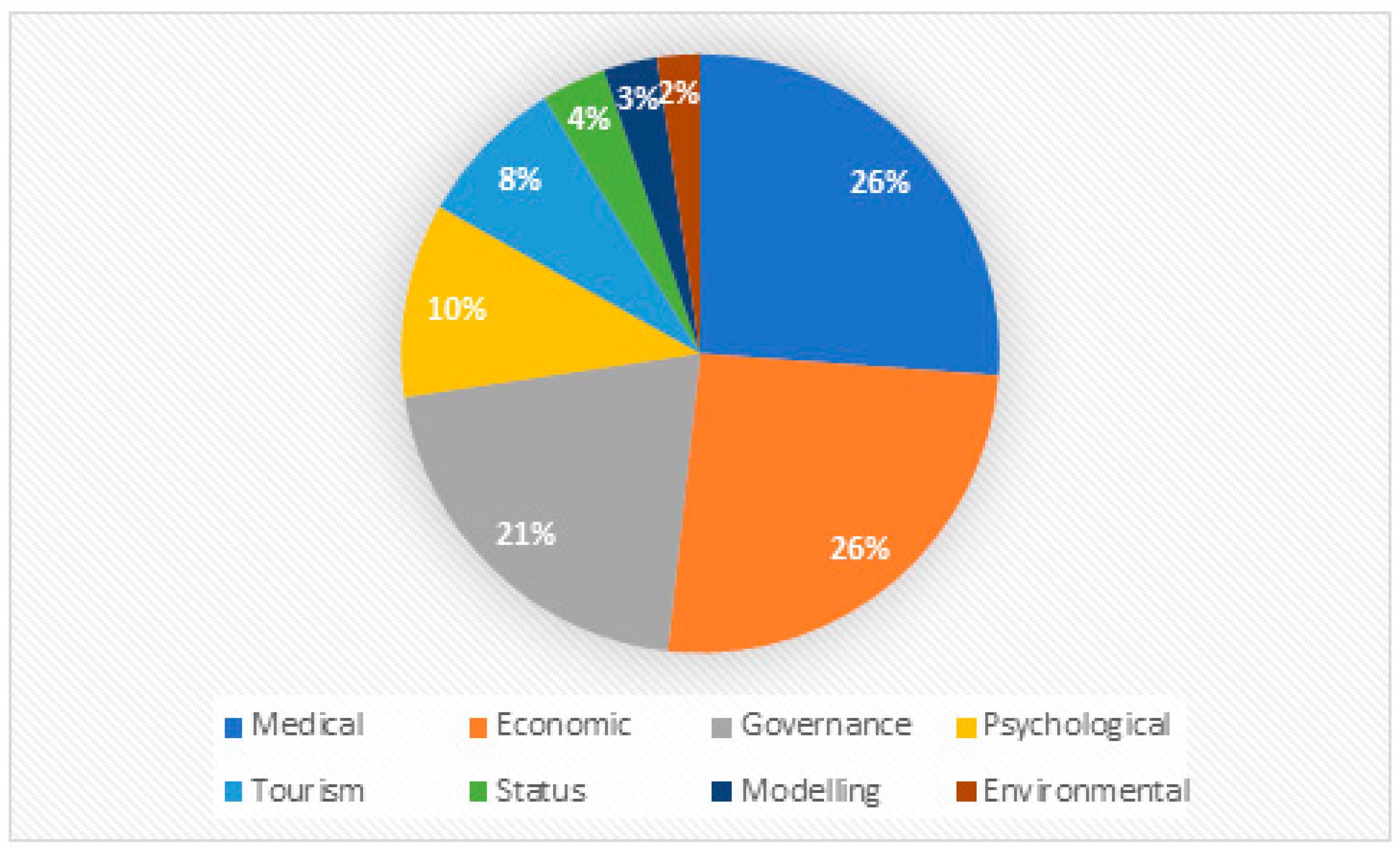

Table 1). The ‘Medical, Economic, and Governance’ classes, with a larger number of words, showed a higher percentage of appearance in the news. As is evident in

Figure 2, a total of 73% of vocabularies were classified into three classes of medical, economic and governance. The highest share (26%) was related to medical and economic, followed by governance (21%). At the bottom of the list lie three vocabulary classes of ‘Status’ (4%), ‘Modelling’ (3%), and ‘Environmental’ (2%). ‘Psychological’ and ‘Tourism’ allocated 10% and 8% of our vocabulary collection, respectively.

5. Discussion

5.1. Earlier News Dissemination across the Globe

Global reactions to COVID-19 by citizens and governments varied during the earlier stages (Milani, 2021). In some countries, governments underestimated the severity, immediacy and pace of the developing situation and efforts to control the pandemic were not as effective compared to countries with governments that acted early and decisively, such as New Zealand, with the strong civil political environment and its strong central government (Jamieson, 2020). It has been found that those countries with early effective measures (e.g., China) have been much more successful to date in containing the disease spread and impacts.

Table 2 lists selected countries or territories worldwide to reveal uncertainties and impacts clouded among almost all poor or wealthy nations.

We could not match each of our selected vocabulary mentioned by news items in these selected countries, but we believe that word-matching in countries that had more success with limiting the spread of the disease and those which did not act appropriately could be reflected in their news items.

A survey was conducted in six countries (Argentina, South Korea, Germany, Spain, the UK, and the US) between late March and early April 2020 and found that the majority of respondents preferred online outlets (including social networks) to obtain news during the pandemic (Nielsen et al., 2020). For instance, in Portugal, people relied on television (92%), digital newspapers (65%), social networks (65%) and internet search engines (57%) during the first week of the state of emergency in the country (Ferreira & Borges, 2020). This compares to Switzerland, where online searching (92.8%), social media (75.2%), and newspapers (both online and paper format, 72.4%) were dominant (Liu et al., 2020). During the confusion and uncertainty that marred those early months, a mixture of correct and incorrect information and news were disseminated. A report showed that Health-related fake news (a misrepresentation of the truth or presentation of false information) (67.2%) constituted the top of the list of news before religiopolitical, political, crime, entertainment, religious, and miscellaneous (Al-Zaman, 2021). Therefore, direct communication to the public was key at these earlier stages, and many countries launched daily brief TV and radio broadcasting programmes to disseminate information. Meanwhile, some countries (e.g. Japan, Taiwan) struggled to transmit crucial public health messages. A study was conducted based on a panel survey to assess the set of behaviours and attitudes of 1052 residents in Japan at the end of March 2020 (Zhang, 2021). In this research, people complained about poor communication during the early stages. The same issue has been raised for Taiwan, where the lack of translation of key messages into different languages became noticeable to non-Taiwanese citizens travelling or residing in Taiwan (Wang et al., 2020). Such language barriers were also noticeable for transmitting knowledge via audio and video clips on COVID-19 for indigenous people in Latin America (Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia) (García et al., 2020).

On the contrary, one of the more effective and accessible communication methods was followed by the New Zealand government which created a COVID-19-dedicated website in 28 languages (Jamieson, 2020). Another study identified that the government of Ghana used “frequent Presidential addresses, Minister’s Press Briefings, designated Covid-19 Website, and Social and Traditional Media to provide information to the citizens” (Antwi-Boasiako & Nyarkoh, 2020, p.1). It has also been reported that Swiss people trusted local and national media and were satisfied with the way their government managed the pandemic crisis by helping them understand the pandemic and the government’s responses (Liu et al., 2020).

5.2. Interpretation of Vocabularies

The lexicon collected from online news media during the early three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in our research were broadly dominated by three key subjects: medical, economic, and governance (

Table 1;

Figure 2). Readers may not find this result surprising, yet it evinces and reflects external and tangible concerns of uncertainty. Analysing 7209 news articles in Bangladesh, Zafri et al. (2021) has also resulted in the same arrays of dominant words reflected in newspapers, including the origin of COVID-19 (‘medical’ in our research) and outbreak, the response of the healthcare system (‘governance’ in our research) and impact of the pandemic on the economy (‘economy’ in our research). In Taiwan, Google searches for COVID-19 related issues (hand washing and face masks) were increased after the 21st of January 2020, when the first imported case to Taiwan was announced (Husnayain et al., 2020).

The outward-looking descriptions of the economy, of medical infrastructure in crises, and of ‘imposed’ restrictions speaks to the exogenous characteristics held at the start of the pandemic and reflects concerns and uncertainty surrounding illness, job security, and income. Here, we elaborate on these top three more resonated vocabulary classes (

Table 1): medical, economic and governance.

5.2.1. Medical

This subject primarily contains critical vocabulary related to problems with sourcing equipment, indications of infection, and the (un)availability of facilities. At the start of the pandemic, very limited testing was available across the world. Thus, vital medical signs of infection (e.g., “cough”, “fever”) were commonly relayed to inform and assure the general public whether they were infected. This snapshot, however, ignores the at-that-time unknown danger and prevalence of asymptomatic cases. Contemporaneously, the other key vocabulary used speaks to health systems in crises – terms such as “gloves”, “mask”, “shortage of equipment”, “doctor”, “patient” and “ICU” being used to describe the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) and other facilities such as hospital beds and personnel. Going hand-in-hand with the absence of widely available testing, the reporting of the crises focused on these struggles of healthcare systems as a way of evidencing the scale, damage and perhaps importantly, proof of the pandemic. The existence of four words used for calling the pandemic in our research (corona, coronavirus, COVID-19, virus) (

Table 1) highlights the confusion surrounding the real name of the disease among news platforms during the first two months. In fact, after some heated exchanges between the US and China to name the disease and the first appearance of the name of “Wuhan Pneumonia” (Liu et al., 2020), the pandemic was eventually called 'COVID-19'' on 12 Feb 2020 (Liu et al., 2020). A global study found that “once COVID-19 was identified, the vocabulary changed to virus family and specific COVID-19 acronyms” (Valentin et al., 2021, p.981). Rarely has a word moved from the jargon of medical professionals to the general public’s everyday vocabulary as quickly as coronavirus (Merriam-Webster, 2021).

5.2.2. Economic

This vocabulary has two interrelated sides: negative consequences of the pandemic on the world and local economies and positive responses to the pandemic. Starting with those negative consequences, terms such as “homelessness”, “jobless”, “layoff”, “unemployment” (

Table 1) directly targeting the personal and human consequences that the pandemic had. It indicates that not only has the pandemic ravaged global healthcare and economic systems, but on one’s everyday lives. Indeed, at the broader level, vocabulary such as “bailout”, “crush”, “wiped-out”, “recession” relate to a national and international level of effect on the world – these somewhat decontextualised terms working with the personalised terms to tell a story of severe and prolonged economic damage. However, in response to this damage, various measures were rolled out by governments as is evidenced with vocabulary such as “aid”, “benefit”, “economic package”, “furlough”, “rescue” the concurrent usage of these terms indexing the immediacy and emergency of response required.

Uncertainties surrounding the spread and control of this unprecedented disease has caused governments to continue the preventive and curative procedures, e.g., social distancing: (Weill et al., 2020). However, despite drastic measures taken by all countries across the globe to manage the pandemic, virus transmission and variation have not been halted for almost two years. These preventive measures have culminated catastrophic impacts on every economic aspect. From supply chain (Lopes de Sousa Jabbour et al., 2020) to food security (Woertz, 2020), a wide range of economic sectors have been affected globally.

5.2.3. Governance

As shown in

Table 1, the high occurrence of words related to management and administration aspects proposed by governments (‘Governance’ class) indicate controversies surrounding making decisions and executing operations among governments. Those words such as ”accelerate, warning, enforce, response, risk”indicate the emergency atmosphere clouded the countries during the first three months. Words such as ”control, curb, stay-at-home, social distancing”indicate the necessity of self-isolation for better control of situations propounded by the governments.

While increased government effectiveness has shown a high correlation with decreased COVID fatality rates (Serikbayeva et al., 2020), mismanagement of the pandemic has created chaos and revealed caveats in governance in many states. They have exposed the vulnerability and unpreparedness of public governments in decision-making in response to the pandemic. In our research, words such as “backfire, grappling, crippling, response, risk, trouble, warning” (

Table 1) highlight these negative views and gaps in governance.

Across these three dominant subjects in our research, a central element is temporality – the sudden emergence and rapid response required to overcome such a challenge. More than this, though, the temporality of the vocabulary classes themselves and the changing nature of the words which belong in each class. Take, for example, the ‘equipment’ sub-class in the medical class in our collection; this vocabulary was often used in the context of the need for healthcare professionals to have access to personal protective equipment and, indeed, some countries failures to procure adequate supplies. Further studies might capture reports about protests against government-imposed restrictions regarding mask-wearing. The ever-changing makeup of the pandemic can thus be seen in the language choices used by online media, and the current study presents one small window from the start of the pandemic to showcase how the general response to these challenges was first framed.

5.3. What Do Online Dictionaries Say?

Similar to findings in this research, the online version of Merriam-Webster Dictionary has also recorded an increase in the number of few vocabulary searches known as the “Word of the Year for 2020” during the first three months (Merriam-Webster, 2021). Their result showed that the word “pandemic” was unsurprisingly the top lookup among all in 2020. The first big spike of the search was recorded on February 3rd when the ‘pandemic’ was looked up 1621%, and it reached an average of 4000% by early March compared to the year 2019 (Ibid). On March 11th, when COVID-19 was declared as a pandemic by WHO, ‘pandemic’ saw the single largest spike in dictionary traffic in 2020, showing an increase of 115,806% over lookups on that day in 2019 (Ibid). Other Pandemic-related words have been summarised in

Table 3.

6. Conclusion

This paper strives to open an interdisciplinary perspective to provide new vocabulary insights, especially during unprecedented global events. Our discussion of vocabulary focuses on two pivotal aspects: early communications across the globe and interpretation of vocabularies. For both sections, temporality in the pandemic timeline is essential in making sense of the predominant vocabulary – the early responses and terms used evince the significant challenges faced globally, notably the trouble with identifying who has the disease and its spread in the absence of widespread testing. Also, it reveals the dichotomous reporting of the pandemic from the (inter)national level of economic damage to the micro-level personal hardship faced by many. The present study solely focused on vocabulary classes selected as representative of, and rooted in, their prime usage during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We only covered online news media, but social media is another viable platform for such studies and, indeed, would provide a perspicuous site for understanding aspects of information dissemination and legitimacy (e.g. Cinelli et al., 2020).

In sketching these vocabulary classes, there are many relevant words and classes that we did not have space to fully discuss or mention. We thus encourage readers to present new ideas and approaches to explore such event-based vocabularies with various contextual and grammatical conditions.

Studying lexicons in the context of a world-changing event offers a window, in a macro sense, into the cumulative responses of nations as the globe began to comprehend the magnitude of the challenges being faced.

References

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D. Wildlife and newspaper reporting in Iran: A data analysis approach. Animals 2021, 11, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiraslani, F.; Dragovich, D. Portraying the water crisis in Iranian newspapers: An approach using Structure Query Language (SQL). Water 2021, 13, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaman, M.S. COVID-19-Related social media fake news in India. Journalism and Media 2021, 2, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boasiako, J.; Nyarkoh, E. Government Communication during the Covid-19 Pandemic; the Case of Ghana. International Journal of Public Administration 2020, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, E.; Juncal, M. J. L.; Umeno, R. K. P.; Peixoto, D. A.; Nguyen, K.; Sahin, O. Effectiveness of the early response to COVID-19: Data analysis and modelling. Systems 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Scientific Reports 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.; Davila, A.; Regis, M.; Kraus, S. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Global Transitions 2020, 2, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J. M.; Pavlenko, A. Emotion vocabulary in interlanguage. Language Learning 2002, 52, 263–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkhembayar, R.; Dickinson, E.; Badarch, D.; Narula, I.; Warburton, D.; Thomas, G. N.; Ochir, C.; Manaseki-Holland, S. Early policy actions and emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Mongolia: experiences and challenges. The Lancet Global Health 2020, 8, e1234–e1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Discourse and Social Change. Polity Press. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, G. B.; Borges, S. Media and Misinformation in Times of COVID-19: How People Informed Themselves in the Days Following the Portuguese Declaration of the State of Emergency. Journalism and Media 2020, 1, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G. M.; Haboud, M.; Howard, R.; Manresa, A.; Zurita, J. Miscommunication in the COVID-19 Era. Bulletin of Latin American Research 2020, 39, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnayain, A.; Fuad, A.; Su, E. C. Y. Applications of Google Search Trends for risk communication in infectious disease management: A case study of the COVID-19 outbreak in Taiwan. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 95, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, T. “Go Hard, Go Early”: Preliminary Lessons From New Zealand’s Response to COVID-19. American Review of Public Administration 2020, 50, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J. B.; Humă, B.; Ristimäki, H.-L.; Ferraz de Almeida, F.; Doehring, A.; de Almeida, F. F.; Doehring, A. Speaking out against everyday sexism: Gender and epistemics in accusations of “mansplaining”. Feminism and Psychology 2021, 31, 502–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, I. Lost for Words Amongst Disaster Risk Science Vocabulary? International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2018, 9, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shan, J.; Delaloye, M.; Piguet, J.-G.; Glassey Balet, N. The Role of Public Trust and Media in Managing the Dissemination of COVID-19-Related News in Switzerland. Journalism and Media 2020, 1, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A. B.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J.; Hingley, M.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E. L.; Ramsden, G.; Twigg, D. Sustainability of supply chains in the wake of the coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: lessons and trends. Modern Supply Chain Research and Applications 2020, 2, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Prisno, D. E.; Essar, M. Y.; Ahmadi, A.; Lin, X.; Adebisi, Y. A. Conflict and COVID-19: A double burden for Afghanistan’s healthcare system. Conflict and Health 2020, 14, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Pinto, J.; Liu, M. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities 2021, 112, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrriam-Webster, 202. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/word-of-the-year/pandemic (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Milani, F. COVID-19 outbreak, social response, and early economic effects: a global VAR analysis of cross-country interdependencies. Journal of Population Economics 2021, 34, 223–252. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v25s1/en_1413-8123-csc-25-s1-2423.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- MW-Function, 2021. “Function.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/function (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- MW-Implication, 2021. “Implication.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/implication (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Nielsen R K, Fletcher R, Newman N, Brennen JS, and Howard PN, 2020. Navigating the ‘Infodemic’: How people in six countries access and rate news and information about coronavirus.

- Piekkari, R.; Tietze, S.; Angouri, J.; Meyer, R.; Vaara, E. Can you Speak Covid-19? Languages and Social Inequality in Management Studies. Journal of Management Studies 2021, 58, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Urbanization. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Serikbayeva, B.; Abdulla, K.; Oskenbayev, Y. State Capacity in Responding to COVID-19. International Journal of Public Administration 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Okan, O.; Kondilis, B.; Levin-Zamir, D. Rebranding social distancing to physical distancing: calling for a change in the health promotion vocabulary to enhance clear communication during a pandemic. Global Health Promotion 2021, 28, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- racy K. (2016). Discourse, identity, and social change in the marriage equality debates. Oxford University Press.

- UNISDR, 2015. Words into action: Man-made and technological hazrds. UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Rue de Varembé CH1202, Geneva – Switzerland.

- Valentin, S.; Mercier, A.; Lancelot, R.; Roche, M.; Arsevska, E. Monitoring online media reports for early detection of unknown diseases: Insight from a retrospective study of COVID-19 emergence. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2021, 68, 981–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vine, V.; Boyd, R.L.; Pennebaker, J.W. Natural emotion vocabularies as windows on distress and well-being. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. J.; Ng, C. Y.; Brook, R. H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 2020, 32, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, J.A.; Stigler, M.; Deschenes, O.; Springborn, M.R. Social distancing responses to COVID-19 emergency declarations strongly differentiated by income. PNAS 2020, 117, 19658–19660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (2020). WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Woertz, E. Wither the self-sufficiency illusion? Food security in Arab Gulf States and the impact of COVID-19. Food Security 2020, 12, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chen, B.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H. Culture, Institution, and COVID-19 First-Response Policy: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Thirty-One Countries. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 2021, 23, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafri, N. M.; Afroj, S.; Nafi, I. M.; Hasan, M. M. U. A content analysis of newspaper coverage of COVID-19 pandemic for developing a pandemic management framework. Heliyon 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. People’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic during its early stages and factors affecting those responses. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2021, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).