Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

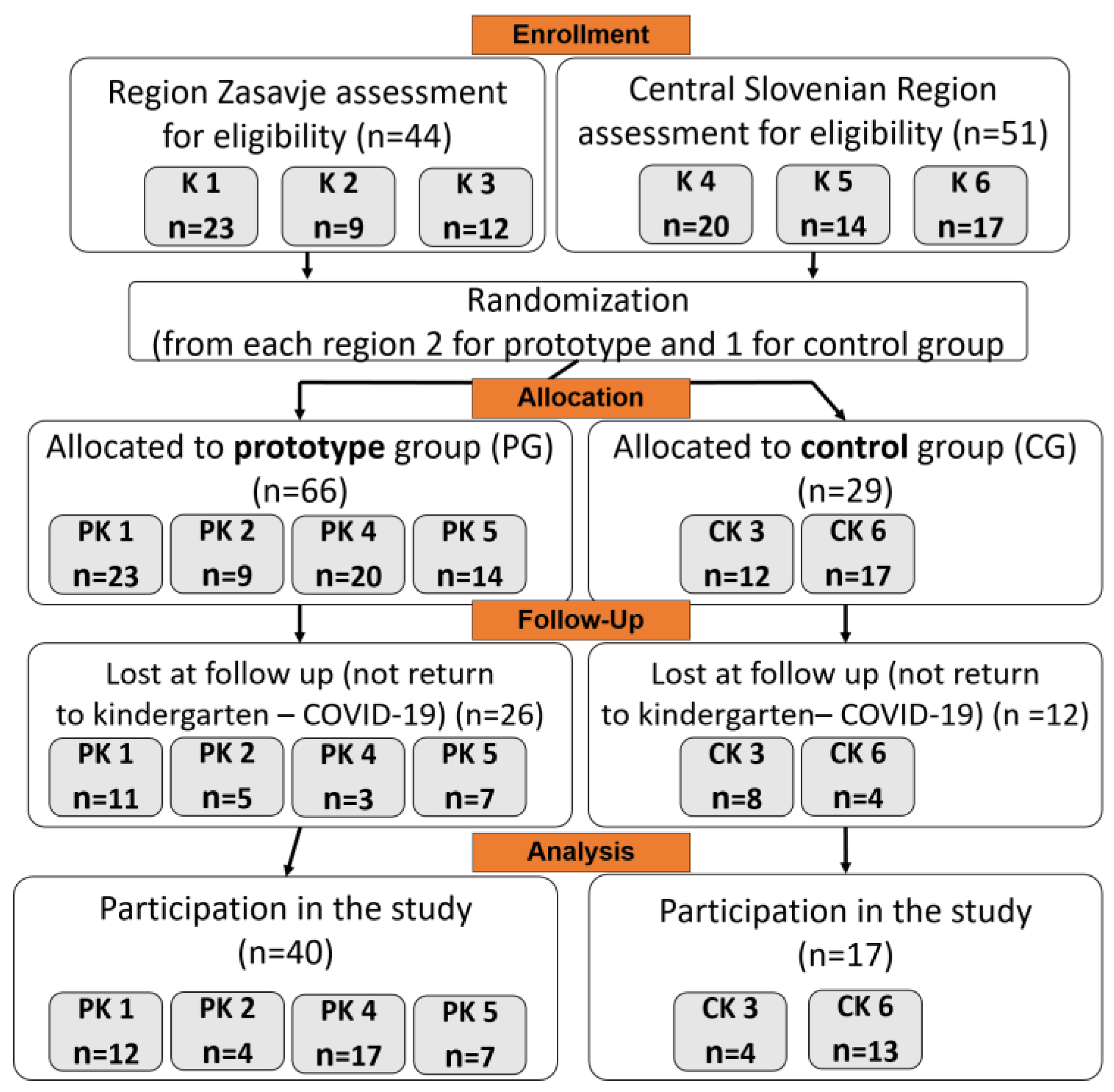

2.1. Study design

2.2. Participants and Settings

2.3. Anthropometric measurements

2.4. Assessment of food groups offered in kindergarten menus/meals

2.5. Dietary intake in kindergartens

2.6. Dietary intake outside kindergartens

2.7. Dietary intake data processing

2.8. Statistical methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants and settings

3.2. Anthropometric measurements

3.3. Food groups offered in kindergartens

3.4. Energy, macronutrient and sodium content in kindergarten meals

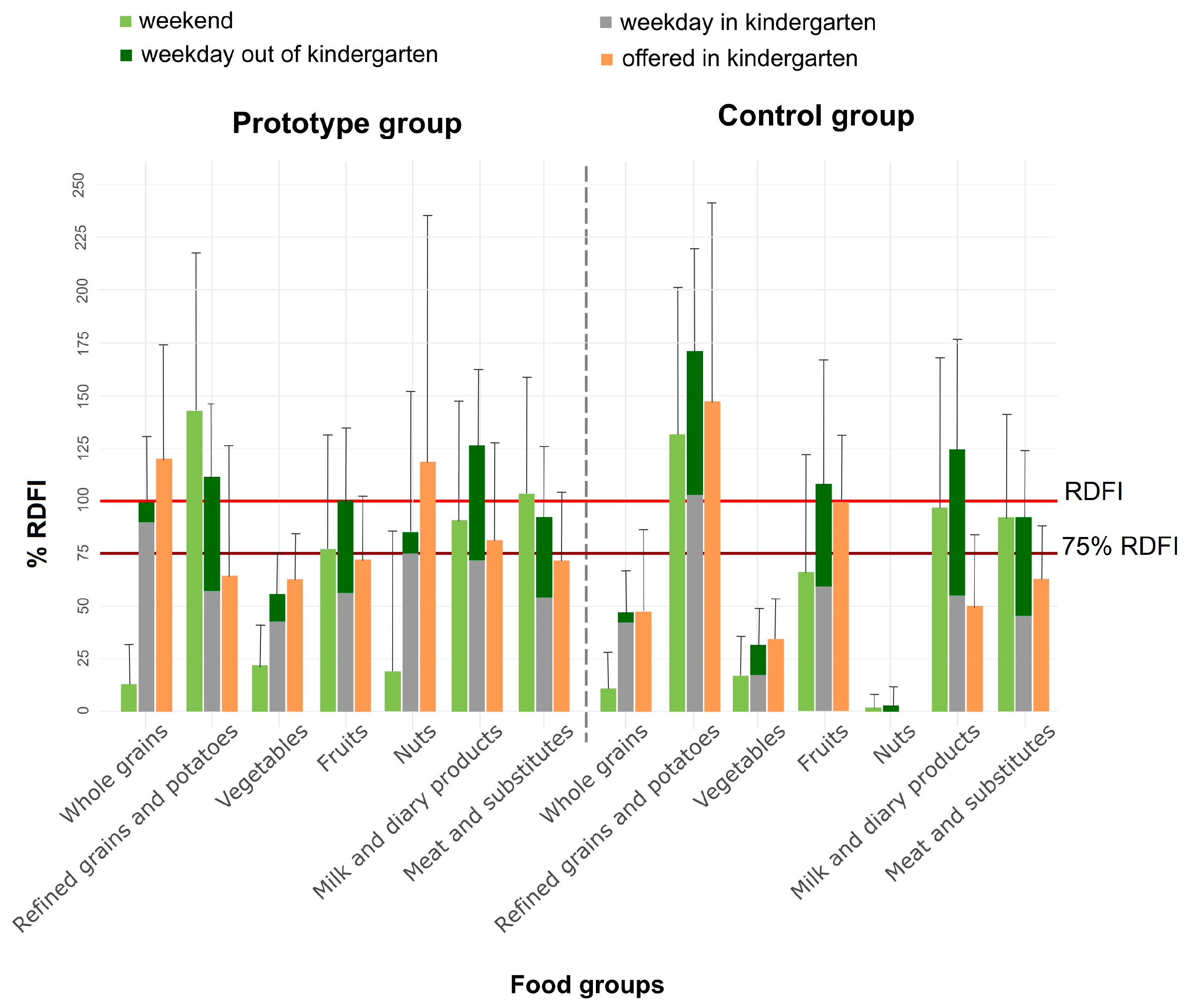

3.5. Food intakes in kindergartens and outside kindergartens on weekdays in PG and CG participants

3.6. Weekend food intake among participants of PG and CG and comparison with weekday intake

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- GBD 2016. Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1151-1210. [CrossRef]

- Bowen KJ, Sullivan VK, Kris-Etherton PM, Petersen KS. Nutrition and cardiovascular disease—an update. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2018, 20, 8. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000490 (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Fernandez-Jimenez R, Al-Kazaz M, Jaslow R, Carvajal I, Fuster V. Children present a window of opportunity for promoting health: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72, 3310-3319. [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni S, Arrizza C, Vecchi F, Tedeschi S. Determinants of children's eating behavior. Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 94(6Suppl), 2006S-2011S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.001685. [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. A World Ready to Learn: Prioritizing quality early childhood education. 2019. Available online: https://uni.cf/world-ready-to-learn-data (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Eurydice Brief: Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union 2019, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs VA, Messing S, Sandu P, Nardone P, Pizzi E, Hassapidou M, Brukalo K, Tecklenburg E, Abu-Omar K. Improving the food environment in kindergartens and schools: an overview of policies and policy opportunities in Europe. Food Policy 2020, 96, 101848. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Food consumption data. 2022. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/data-report/food-consumption-data (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- NIJZ. Različni vidiki prehranjevanja prebivalcev Slovenije: v starosti od 3 mesecev do 74 let. 2019. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/razlicni_vidiki_prehranjevanja_prebivalcev_slovenije.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Gabrijelčič Blenkuš M, Pograjc L, Gregorčič M, Adamič M, Čampa A. Smernice zdravega prehranjevanja v vzgojno-izobraževalnih ustanovah (od prvega leta starosti naprej). Ministry of Health 2005. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/smernice_zdravega_prehranjevanja_v_viu.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- NIJZ. Strokovno spremljanje prehrane s svetovanjem v vzgojno-izobraževalnih zavodih v letu 2018. 2018. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/porocilo_spremljanja_pehrane_v_viz_2018_gn_0.pdf NIJZ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Tugault-Lafleur CN, Black JL. Lunch on school days in Canada: examining contributions to nutrient and food group intake and differences across eating locations. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020, 120, 1484-1497. [CrossRef]

- Luecking CT, Mazzucca S, Vaughn AE, Ward DS. Contributions of early care and education programs to diet quality in children aged 3 to 4 years in central North Carolina. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020, 120, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkalo L, Nissinen K, Skaffari E, Vepsäläinen H, Lehto R, Kaukonen R, Koivusilta L, Sajaniemi N, Roos E, Erkkola M. The contribution of preschool meals to the diet of Finnish preschoolers. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2018, 137, 67-492. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet 2019, 393, 434–445. [CrossRef]

- Ros, E. Eat nuts, live longer. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017, 70, 2533–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieffers JRL, Ekwaru JP, Ohinmaa A, Veugelers PJ. The economic burden of not meeting food recommendations in Canada: the cost of doing nothing. PLoS One 2018, 13, 0196333. [CrossRef]

- Hasnin S, Dev DA, Tovar A. Participation in the CACFP ensures availability but not intake of nutritious foods at lunch in preschool children in child-care centers. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020, 120, 1722-1729. [CrossRef]

- Sisson SB, Kiger AC, Anundson KC, Rasbold AH, Krampe M, Campbell J, Degrace B, Hoffman L. Differences in preschool-age children's dietary intake between meals consumed at childcare and at home. Prev Med Rep 2017, 6,33-37. [CrossRef]

- Cole TJ, Lobstein T. Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012, 7, 284-294. [CrossRef]

- Korošec M, Golob T, Bertoncelj J, Stibilj V, Seljak BK (2013) The Slovenian food composition database. Food Chem 2013, 140, 495–499. [CrossRef]

- Ross AB, van der Kamp JW, King R, Lê KA, Mejborn H, Seal CJ, Thielecke F, Healthgrain Forum. Perspective: a definition for whole-grain food products-recommendations from the healthgrain forum. Adv Nutr 2017, 8, 525-531. [CrossRef]

- Jones JM, García CG, Braun HJ. Perspective: whole and refined grains and health-evidence supporting "Make half your grains whole". Adv Nutr 2020 11, 492-506. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. General principles for the collection of national food consumption data in the view of a pan-European dietary survey. EFSA Journal 2009, 7, 1435.

- NIJZ. Slikovno gradivo za določanje vnosa živil. 2017. Available online: Artboard 1 (nijz.si) (accessed 20 September 2022).

- Fagerland, M.W.; Sandvik, L. Performance of five two-sample location tests for skewed distributions with unequal variances. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2009, 30, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2018. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/tool/81287/r-a-language-and-environment-for-statistical-computing (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Deon, V.; Del Bo’, C.; Guaraldi, F.; Abello, F.; Belviso, S.; Porrini, M.; Riso, P.; Guardamagna, O. Effect of hazelnut on serum lipid profile and fatty acid composition of erythrocyte phospholipids in children and adolescents with primary hyperlipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlic, M.; Jug, U.; Battelino, T.; Levart, A.; Dimitrovska, I.; Albreht, A.; Korošec, M. Antioxidant-rich foods and nutritional value in daily kindergarten menu: A randomized controlled evaluation executed in Slovenia. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, J.R.; Cezaro, C.D.; Fisberg, R.M.; Fisberg, M.; Vitolo, M.R. Estimation of energy and macronutrient intake at home and in the kindergarten programs in preschool children. J. Pediatr. 2010, 86, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreyeva, T.; Kenney, E.L.; O’Connell, M.; Sun, X.; Henderson, K.E. Predictors of nutrition quality in early child education settings in Connecticut. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romo-Palafox, M.J.; Ranjit, N.; Sweitzer, S.J.; Roberts-Gray, C.; Byrd-Williams, C.E.; Briley, M.E.; Hoelscher, D.M. Adequacy of parent-packed lunches and preschooler's consumption compared to dietary reference intake recommendations. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2017, 36, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, S.M.; Khoury, J.C.; Kalkwarf, H.J.; Copeland, K. Dietary intake of children attending full-time child care: What are they eating away from the childcare center? J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1472–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embling, R.; Pink, A.E.; Gatzemeier, J.; Price, M.D.; Lee, M.; Wilkinson, L.L. Effect of food variety on intake of a meal: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 716–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, L.S.; Meengs, J.S.; Birch, L.L.; Rolls, B.J. Serving a variety of vegetables and fruit as a snack increased intake in preschool children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, L.S.; Sanchez, C.E.; Smethers, A.D.; Keller, K.L.; Rolls, B.J. Portion size can be used strategically to increase intake of vegetables and fruits in young children over multiple days: A cluster-randomized crossover trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spill, M.K.; Birch, L.L.; Roe, L.S.; Rolls, B.J. Hiding vegetables to reduce energy density: An effective strategy to increase children's vegetable intake and reduce energy intake. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrosa, S.; Luque, V.; Grote, V.; Closa-Monasterolo, R.; Ferré, N.; Koletzko, B.; Verduci, E.; Gruszfeld, D.; Xhonneux, A.; Escribano, J. Fibre intake is associated with cardiovascular health in European children. Nutrients 2020, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Bi, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, P.; Tong, J.; Peng, X.; Tian, J.; Liang, X. Protective effects of appropriate amount of nuts intake on childhood blood pressure level: A cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 793672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, L.C.; Hill, A.M.; Carter, S.; Coates, A.M. The effect of nut consumption on diet quality, cardiometabolic and gastrointestinal health in children: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, T.; Sicherer, S. Current perspectives on tree nut allergy: A review. J. Asthma Allergy 2018, 11, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Emmett, P.M. Picky eating in children: Causes and consequences. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2019, 78, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Food Groups 1 | Meat and Substitutes (g) | Milk and Dairy Products (g) | Fruits (g) | Vegetables (g) | Nuts (g) | Whole Grains (g) | Refined Grains and Potatoes (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable of interest | RDFI 2 4–6 years (75% RDFI) 3 |

110 (82.5) | 400 4 (300) |

200 (150) |

300 (225) |

11 5 (8) |

115 6 (86) |

115 6 (86) |

| Offered in kindergarten Mean (SD) 7 | PG | 78 (36) | 325 (162) | 143 (61) | 188 (66) | 14 (13) | 137 (62) | 74 (71) |

| CG | 69 (28) | 200 (136) | 198 (64) | 103 (58) | 0 | 54 (45) | 169 (108) | |

| p-value | 1 | 0.231 | 0.233 | 0.011 * | <0.001 * | 0.002 * | 0.152 | |

| Weekday in kindergartens Mean (SD) 8 | PG | 59 (23) | 289 (94) | 112 (34) | 136 (48) | 8 (6) | 106 (35) | 66 (23) |

| CG | 50 (24) | 220 (101) | 134 (74) | 60 (51) | 0 | 49 (26) | 119 (48) | |

| p-value | 1 | 0.137 | 1 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.002 * | |

| Weekdays outside kindergartens Mean (SD) 9 | PG | 42 (28) | 216 (111) | 88 (65) | 33 (31) | 0.8 (3) | 9 (13) | 62 (39) |

| CG | 51 (29) | 275 (199) | 82 (64) | 35 (36) | 0.3 (1) | 5 (10) | 78 (39) | |

| p-value | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total weekdays Mean (SD) |

PG | 101 (37) | 505 (145) | 200 (80) | 169 (59) | 8.3 (7) | 115 (36) | 128 (40) |

| CG | 101 (35) | 495 (210) | 216 (118) | 95 (53) | 0.3 (1) | 54 (23) | 197 (56) | |

| p-value | 1 | 1 | 1 | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | <0.001 * | 0.005 * | |

| Total Weekend Mean (SD) 10 |

PG | 113 (61) | 365 (227) | 153 (109) | 66 (58) | 2 (7) | 13 (22) | 164 (86) |

| CG | 101 (54) | 388 (285) | 131 (112) | 52 (57) | 0.2 (0.7) | 13 (20) | 152 (80) | |

| p-value | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.288 | 1 | 1 |

| Energy (kcal) | Total Fat (g) | Protein (g) | CH (g) | DF (g) | Na (mg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable of interest | DRI 1 4–6 years. (75% DRI) 2 |

1550 (1162) |

52–60 (39–45) |

39–58 (29–44) |

>194 (>146) |

˃15 (˃11) |

<1180 (880) |

| Offered in kindergartens Mean (SD) 3 |

PG | 1115 (221) | 43 (12) | 39 (7) | 143 (31) | 20 (5) | 1983 (1148) |

| CG | 883 (178) | 25 (12) | 35 (8) | 128 (30) | 14 (5) | 1605 (718) | |

| p-value | 0.031 * | <0.001 * | 1 | 1 | 0.017 * | 1 | |

| Weekday in kindergartens Mean (SD) 4 |

PG | 830 (176) | 30 (8) | 29 (6) | 112 (23) | 15 (3) | 1478 (400) |

| CG | 664 (239) | 20 (8) | 28 (11) | 94 (34) | 10 (4) | 1126 (521) | |

| p-value | 0.097 | <0.001 * | 1 | 0.334 | <0.001 * | 0.196 | |

| Weekdays outside kindergartens Mean (SD) 5 | PG | 660 (206) | 25 (9) | 22 (8) | 87 (30) | 6 (2) | 687 (286) |

| CG | 799 (289) | 32 (15) | 27 (8) | 101 (37) | 6 (3) | 757 (366) | |

| p-value | 0.508 | 0.587 | 0.227 | 0.956 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total weekdays Mean (SD) |

PG | 1486 (250) | 55 (12) | 50 (10) | 198 (35) | 21 (4) | 2154 (463) |

| CG | 1462 (317) | 52 (16) | 54 (11) | 195 (46) | 16 (5) | 1910 (517) | |

| p-value | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.010 * | 0.627 | |

| Total Weekend Mean (SD) 6 |

PG | 1336 (374) | 50 (17) | 48 (14) | 173 (56) | 11 (5) | 1648 (852) |

| CG | 1440 (289) | 57 (15) | 48 (8) | 183 (44) | 12 (3) | 1519 (527) | |

| p-value | 1 | 0.808 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).