Introduction

A cholecystectomy is a surgical procedure that removes the gall bladder, typically done to treat gallstone disease. There are two general approaches to performing the surgery, open cholecystectomy (OC) and laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). The first cholecystectomy was performed in 1867 by Carl Johann August Langerbuch and has since become one of the most commonly performed abdominal surgeries. [

2,

12] OC is usually performed via a right subcostal incision, through which the gallbladder is exposed, mobilized, and removed. [

10] LC, which was first performed in 1985, has since become the predominant method preferred by surgeons, with approximately 90 percent of such surgeries being done in this manner. [

8,

9] It is considered the gold standard for cholelithiasis treatment due to better outcomes compared to OC. [

1,

11,

14,

19] The biggest advantages of LC are improved recovery time, less hospitalization time, and less postoperative pain. [

6] Despite these advantages, there are still indications for OC to be performed, generally from an inability to perform the LC. This includes instances where complications occur during an LC and the operation needs to be converted to OC, when the patient is unlikely to tolerate the LC, if cancer of the gallbladder is suspected, or if the cholecystectomy is being performed as part of a larger operation. [

5] Additionally, despite LC generally having better outcomes, it is associated with a higher rate of bile duct injury as well as possibly increased operative morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis patients, though there is conflicting data on this. [

4,

26] However there is evidence that performing LC early instead of delaying it is associated with more positive outcomes, including reduced hospitalization duration. [

7,

14]

One of the most serious complications is myocardial injury. Plaque rupture and high myocardial oxygen demand during surgery is the major cause of myocardial infarction

. It has been reported that in patients 45 years or older undergoing major non-cardiac surgery, over one percent will die from myocardial injury within 30 days. [

3,

13] There is evidence that overall myocardial injury rate after cholecystectomy is low. [

14] However, there is not any research that examines the differences in myocardial injury between OC and LC. To this end, the current article looks to compare inpatient outcomes for these two procedures regarding the occurrence of myocardial infarctions and mortality.

Methods

Data Collection and Data Sources

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was used in this study. The NIS, which is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States, was developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project to allow for the analysis of rare conditions, uncommon treatments, and special populations. The NIS database contains primary and secondary diagnoses for over seven million hospital admissions annually across more than 1000 hospitals nationwide. This provides a stratified sample of patients from approximately 20% of U.S. community hospitals. The database is de-identified, exempt from IRB approval, and publicly available for analysis of nationwide trends in healthcare utilization and outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software was used to perform retrospective univariate and multivariate analyses on NIS data from 2010 through 2014 to compare the inpatient outcomes for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy regarding the occurrence of myocardial infarction and mortality. For univariate analysis, a chi-squared test was performed for five years. For multivariate logistic regression analysis, we adjusted for age on admission, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, morbid obesity, and hypertension from 2010 and 2014. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for both analyses. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

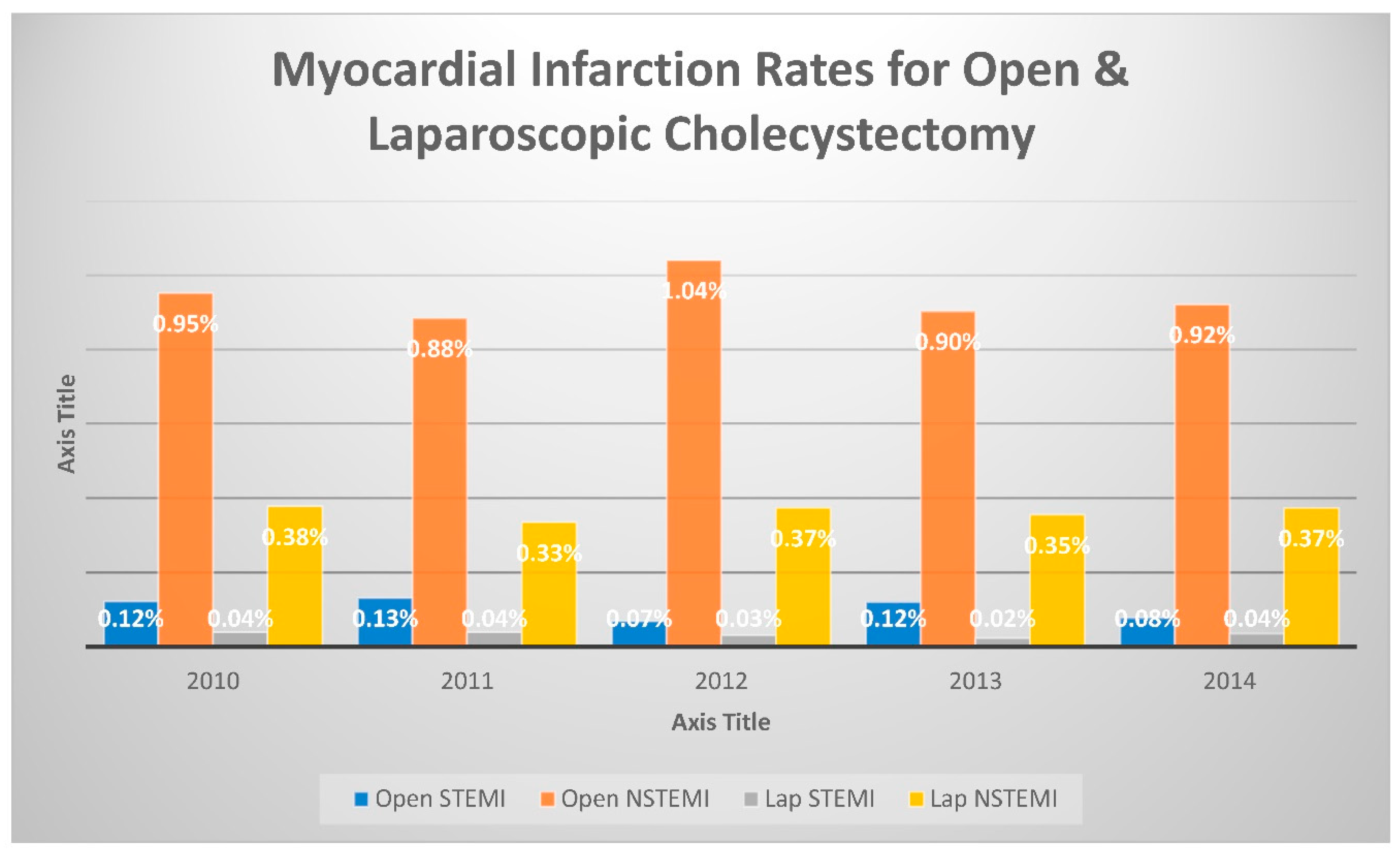

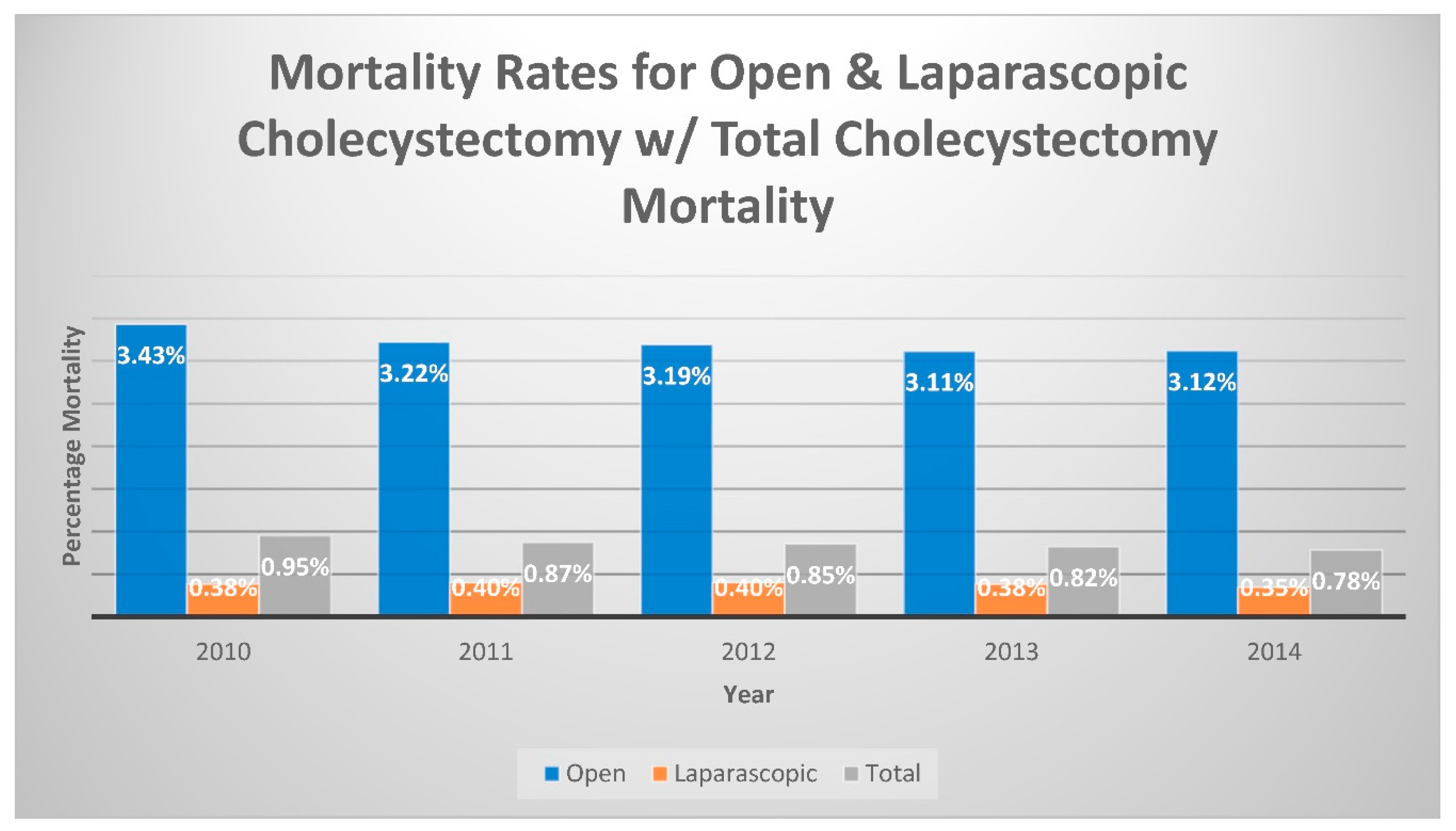

Table 1 showing bassline characteristics. In the 2010 database, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) occurred at a higher rate, 0.12%, of patients who underwent an OC, compared to 0.04% of patients who had an LC performed (Odds ratio [OR]: 3.117; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.756-5.534; p<0.001). Similarly, Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) incidence was higher in those patients who had an OC performed (0.95%) than the 0.38% of those who underwent LC. (OR: 2.534; CI: 2.079-3.088; p<0.001). Finally, the mortality rates were also higher for OC than LC, with a 3.43% incidence compared to 0.38%, respectively. (OR: 9.224; CI:7.975-10.320; p<0.001). This association was consistent throughout the five-year period studied, as shown in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Figure 1 demonstrates both STEMI and NSTEMI rates among cholecystectomies (open, laparoscopic, and total).

Figure 2 demonstrates the rate of mortality after cholecystectomy.

Discussion

Cholecystectomies have been one of the most commonly performed surgeries in the United States, and likely will continue to be for the foreseeable future. [

2,

12] As such, it is important to evaluate best practice techniques to ensure optimal patient care. There is a large body of research supporting the notion that laparoscopic cholecystectomy, compared to open cholecystectomy, is the superior method for gallbladder removals, such as the study done by Soper et al. [

11,

19] LC has been shown to have better outcomes in many areas, including patient recovery time and postoperative pain, and is known to be relatively safe, notably with low rates of myocardial infarction and mortality. [

6,

14] The rate of postoperative complications is lower with LC, and the length of the hospital stay from such surgeries is dramatically lower than with OC. [

21] This, in turn, helps to lower healthcare costs for the patient as well as operational cost-effectiveness for hospitals. LC also has the added benefits of faster patient recovery, earlier return of mobility, a quicker return to diet, and overall increased quality of life after surgery. [

27,

28] It has also been shown that the oxygenation status of patients was more greatly impacted by undergoing OC as compared to LC, and that pulmonary function was less affected. While reductions in pulmonary function after surgery happen with either method, functional residual capacity, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, forced vital capacity, and mid-expiratory flow were all significantly less reduced in those who underwent LC compared OC. The LC group also had a much lower incidence of post-operational atelectasis, and for those who did experience it, the symptoms were less severe. This suggests that because LC preserves better tissue oxygenation is the more appropriate option for people suffering from chronic lung disease. [

18,

20,

25]

It is also known that while LC is generally the safer method, there are areas that have not shown any improvement over OC, namely the incidence of post-cholecystectomy hemorrhage, or worse outcomes in the case of inter-operational biliary injuries. [

4,

15] Differences in the immune response to laparoscopic surgeries and their open counterparts have also been observed. It has often been found that patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries experience less immunosuppression than those who have more traumatic, open surgeries. However, it has also been observed for cholecystectomies specifically that cytokine markers of inflammation and immunosuppression were significantly higher in LC over OC, although other studies have shown the opposite; that OC is associated with higher strain on the immune system. [

16,

17,

23,

24] Along with this, it has also been shown that the rate of surgical site infection in LC and OC is not significantly different, despite the increased incisional area in OC. [

22] There are also still clear indications for OC to be performed, such as when the patient is unlikely to tolerate LC . It is usually related technical issues such as adhesions or difficult access or when the gall bladder removal is only part of a larger surgery which requires an open approach. [

5] This goes to show that while overall LC is the superior method of performing cholecystectomies, and is rightfully lauded as the gold standard, it is not without its potential downsides.

With that in mind, we noted that whether LC differs from OC specifically related to myocardial infarction as well as mortality had not been previously determined. While overall LC has been shown to be the superior surgical approach, it is worthwhile to view it from a variety of lenses to find if there are specific conditions in which surgeons may want to consider something else, such as immunosuppression or pulmonary, liver, or in our case, cardiac contraindications. Our study found that open cholecystectomy is associated with higher rates of STEMI, Non-STEMI and a markedly higher rate of mortality in comparison to the laparoscopic approach in a large inpatient database from 2010 through 2014. After multivariate adjustment for age, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, the occurrence of STEMI, Non-STEMI, and mortality remained higher in the open cholecystectomy cohort (mortality multivariate OR 6.4, CI 5.5-7.4, p<0001).

This data suggests that the current understanding of LC, that it should be regarded as the gold standard for treatment of cholelithiasis, is warranted and should remain the first choice for patients needing gallbladder surgery. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed initially by insufflation abdomen up to 15 mmHg of carbon dioxide before small incisions are made. Using a laparoscope and long instruments, the gallbladder is retracted Electrocautery or scalpel is then used to separate the gallbladder from the liver bed completely. Hemostasis is achieved after the abdomen is deflated to 8 mmHg for 2 minutes. Common complications include infection, bleeding, and damage to the surrounding tissues. [

29]

Limitations

The results of this study are limited by its retrospective nature. Furthermore, there may be some coding inaccuracies in the ICD-9-CM codes we analyzed from the NIS database. Since our results are based on an inpatient database, they may not accurately reflect outpatient cases. A randomized trial will give us the final answer.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Sewefy AM, Hassanen AM, Atyia AM, Gaafar AM. Retroinfundibular laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy in difficult cases. International Journal of Surgery. 2017;43:75-80. [CrossRef]

- LANGENBUCH C. Ein fall von exstirpation der gallenblase wegen chronischer cholelithiasis. heilung. Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift. 1882;19:725-727. [CrossRef]

- Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Ramakrishna H, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with noncardiac surgery. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(2):181-187. [CrossRef]

- Khan MH, Howard TJ, Fogel EL, et al. Frequency of biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy detected by ERCP: Experience at a large tertiary referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(2):247-252. [CrossRef]

- Csikesz N, Ricciardi R, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Current status of surgical management of acute cholecystitis in the united states. World J Surg. 2008;32(10):2230-2236. [CrossRef]

- Schirmer BD, Edge SB, Dix J, Hyser MJ, Hanks JB, Jones RS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. treatment of choice for symptomatic cholelithiasis. Ann Surg. 1991;213(6):665-76; discussion 677. [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy KS, Samraj K. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006(4). [CrossRef]

- Reynolds W. The first laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS 5:89-94. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons / Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2001;5:89-94.

- Csikesz NG, Singla A, Murphy MM, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Surgeon volume metrics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(8):2398-2405. [CrossRef]

- Avgerinos C, Kelgiorgi D, Touloumis Z, Baltatzi L, Dervenis C. One thousand laparoscopic cholecystectomies in a single surgical unit using the "critical view of safety" technique. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(3):498-503. [CrossRef]

- Soper NJ, Stockmann PT, Dunnegan DL, Ashley SW. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy the new 'gold standard'? Arch Surg. 1992;127(8):917-923. [CrossRef]

- David, McAneny. Open cholecystectomy. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2008;88(6):1273-1294.

- Writing Committee for the VISION Study Investigators. Association of postoperative high-sensitivity troponin levels with myocardial injury and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2017;317(16):1642-1651.

- Coccolini F, Catena F, Pisano M, et al. Open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery. 2015;18:196-204. [CrossRef]

- Tonolini M, Ierardi AM, Patella F, Carrafiello G. Early cross-sectional imaging following open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a primer for radiologists. Insights Imaging. 2018 Dec;9(6):925-941. [CrossRef]

- Ordemann J, Jacobi CA, Schwenk W, Stösslein R, Müller JM. Cellular and humoral inflammatory response after laparoscopic and conventional colorectal resections. Surg Endosc. 2001 Jun;15(6):600-8. [CrossRef]

- Wu HY, Li F, Tang QF. Immunological effects of laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(6):2077-83. [CrossRef]

- Bablekos GD, Michaelides SA, Analitis A, Lymperi MH, Charalabopoulos KA. Comparative changes in tissue oxygenation between laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. J Clin Med Res. 2015 Apr;7(4):232-41. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Koch OO, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic vs open cholecystectomy in elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 14;20(46):17626-34. [CrossRef]

- Karayiannakis AJ, Makri GG, Mantzioka A, Karousos D, Karatzas G. Postoperative pulmonary function after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1996 Oct;77(4):448-52. [CrossRef]

- Cleary R, Venables CW, Watson J, Goodfellow J, Wright PD. Comparison of short term outcomes of open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Qual Health Care. 1995 Mar;4(1):13-7. [CrossRef]

- Gharde P, Swarnkar M, Waghmare LS, Bhagat VM, Gode DS, Wagh DD, Muntode P, Rohariya H, Sharma A. Role of antibiotics on surgical site infection in cases of open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparative observational study. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2014 Jan;6(1):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Gomatos IP, Alevizos L, Kalathaki O, Kantsos H, Kataki A, Leandros E, Zografos G, Konstantoulakis M. Changes in T-lymphocytes' viability after laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy. Int Surg. 2015 Apr;100(4):696-701. [CrossRef]

- Kohli R, Bansal E, Gupta AK, Matreja PS, Kaur K. To study the levels of C - reactive protein and total leucocyte count in patients operated of open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Jun;8(6):NC06-8. [CrossRef]

- Osman Y, Fusun A, Serpil A, Umit T, Ebru M, Bulent U, Mete D, Omer C. The comparison of pulmonary functions in open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009 Apr;59(4):201-4.

- Awady, Saleh & El Nakeeb, Ayman & Youssef, Tamer & Fikry, Amir & Fouda, El Yamani & Farid, Mohamed. (2008). Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients: A prospective randomized study. International Journal of Surgery. 2009 Volume 7, Issue 1: 66-69. [CrossRef]

- Attwood SE, Hill AD, Mealy K, Stephens RB. A prospective comparison of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992 Nov;74(6):397-400.

- Chen L, Tao SF, Xu Y, Fang F, Peng SY. Patients' quality of life after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2005 Jul;6(7):678-81. [CrossRef]

- Hassler KR, Collins JT, Philip K, et al. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. [Updated 2023 Jan 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan: Https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448145/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).