Submitted:

20 July 2023

Posted:

21 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. SMEs Definitions and Its Challenges

3. Materials and Methods

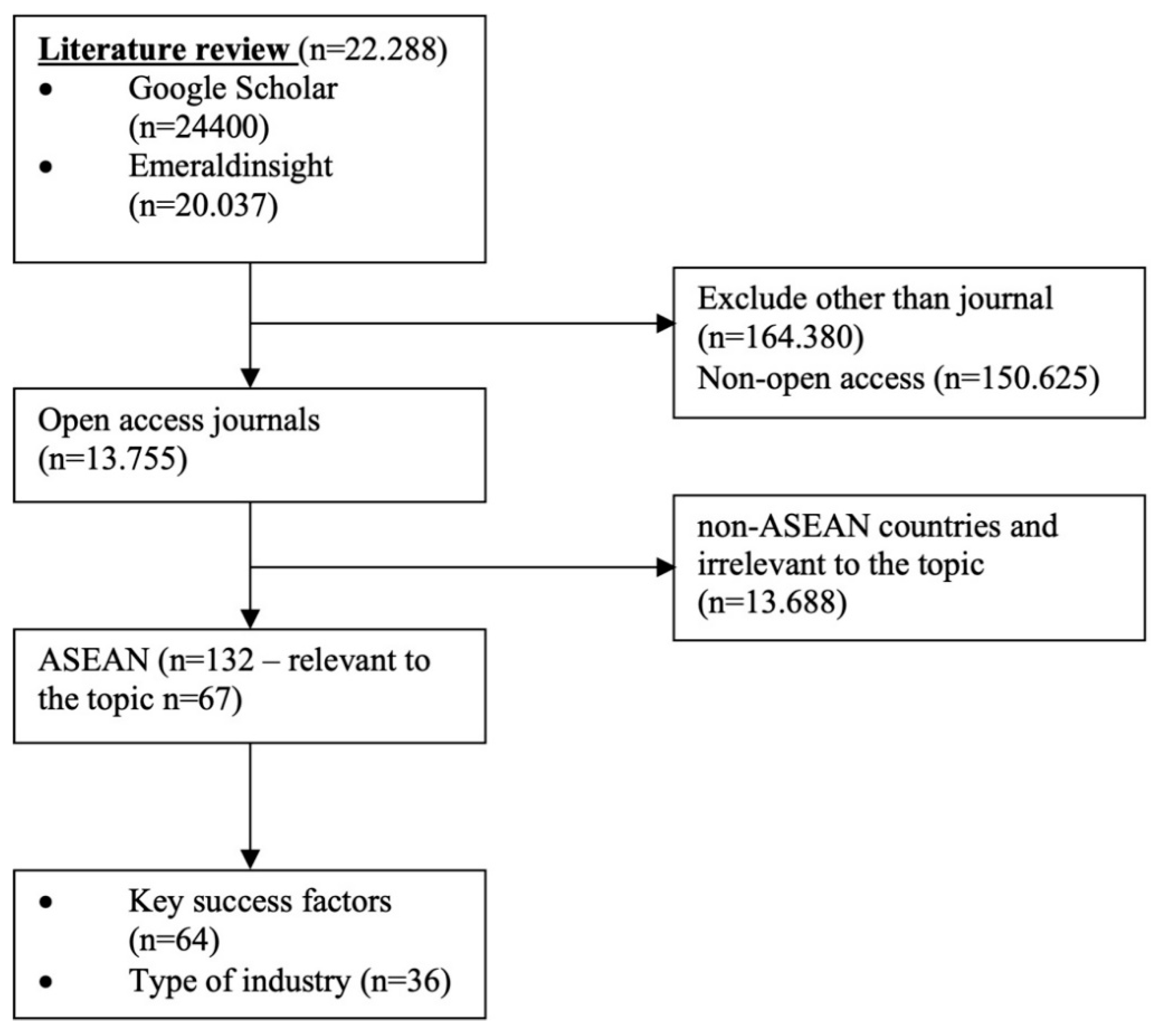

3.1. Meta-Analysis

3.2. Research Design

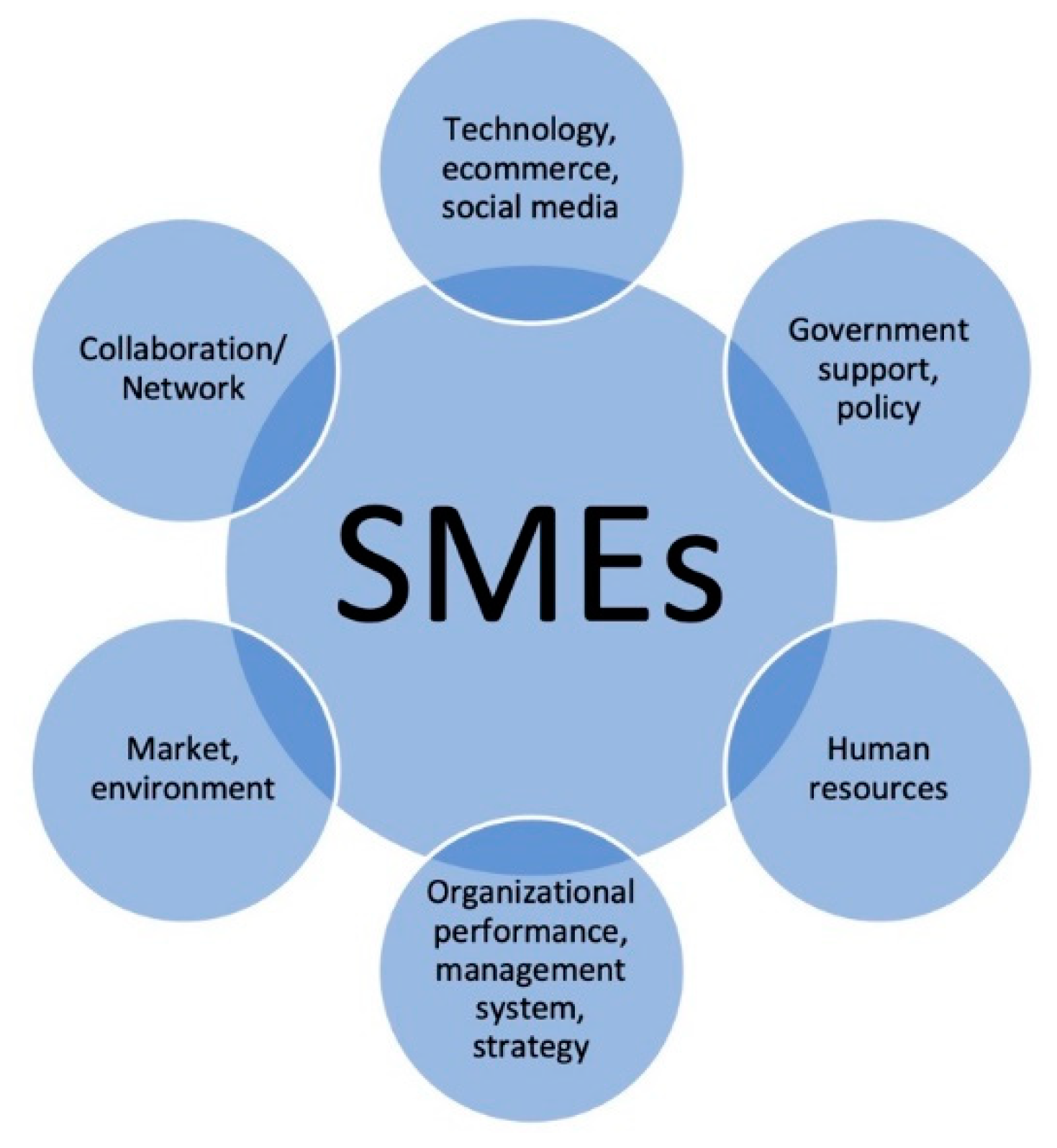

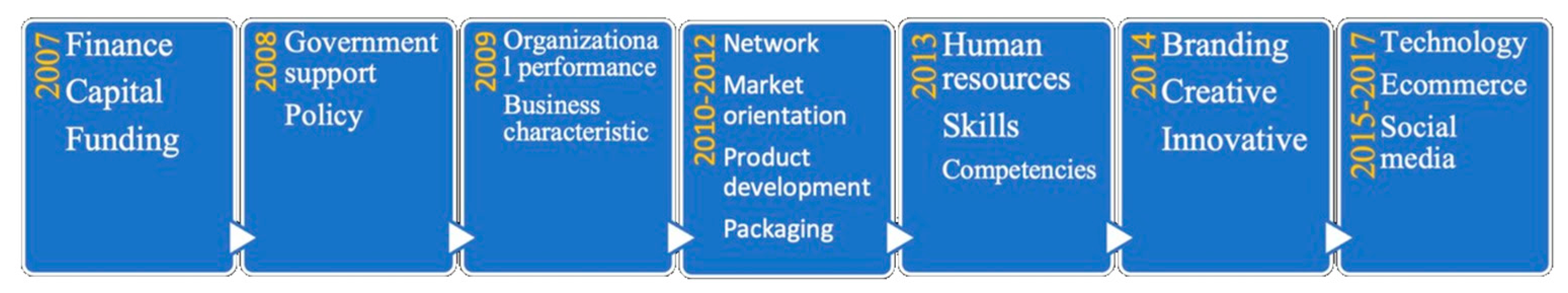

4. Results

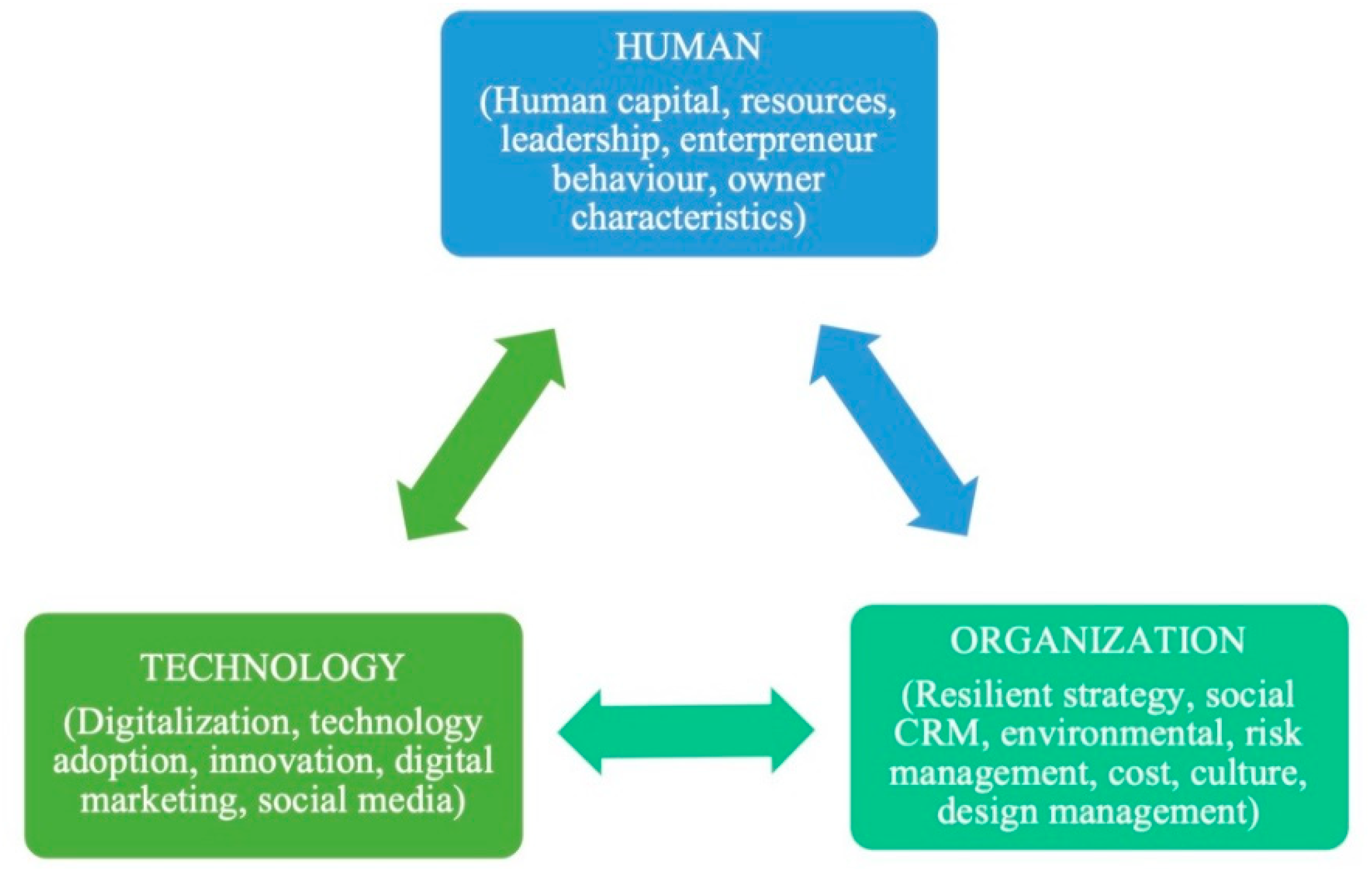

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kadir, S.; Shaikh, J.M. The effects of e-commerce businesses to small-medium enterprises: Media techniques and technology. 2023, p. 050078. [CrossRef]

- Suprapto, B.; Wahab, H.A.; Wibowo, A.J. The implementation of balance score card for performance measurement in small and medium enterprises: Evidence from malaysian health care services. The Asian Journal of Technology Management 2009, 2, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Analysis of credit ratings for small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from Asia. Asian Dev Rev 2015, 32, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Charoensivakorn, P.; Niraula, B. Small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) credit risk analysis using bank lending data: An analysis of Thai SMEs. Journal of Comparative Asian Development 2016, 15, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, T.M.; Hassan, N.H.; Sanusi, Z.M.; Mohamed, Z.M. Board of Directors and Ownership Structure: A Study on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. Jurnal Pengurusan 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.C.; de Sá, E.S. Personal characteristics, business relationships and entrepreneurial performance: Some empirical evidence. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2014, 21, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A.; Perren, L. The role of non-executive directors in UK SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2001, 8, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyowati, E.; Lestari, N.S. Faktor-faktor penentu keberhasilan usaha kecil dan menengah (UKM) Di Kota Yogyakarta. Jurnal Maksipreneur: Manajemen, Koperasi, Dan Entrepreneurship 2016, 6, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambunan, T. Entrepreneurship development: SMES in Indonesia. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 2007, 12, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J.A.; Long, Z.; Lester, D. Competitive strategy, capabilities and uncertainty in small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in China and the United States. Management Decision 2015, 53, 402–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwoko, E. Kajian faktor-faktor penentu keberhasilan small business. Jurnal Ekonomi Modernisasi 2008, 4, 226–239. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, D.P.; Lubis, I. The development of demand for small and medium industries in Indonesia. Development 2019, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Valentina, T.R.; Putera, R.E. ASEAN Economy Community (AEC) Indonesian Politic of Trade in Contending with the Simple Market Based Production. Researchers World 2016, 7, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.R.; Akhter, F.; Sultana, M.M. SMEs in Covid-19 Crisis and Combating Strategies: A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and A Case from Emerging Economy. Operations Research Perspectives 2022, 9, 100222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasiukovich, S.; Haddara, M. Social CRM in SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. Procedia Comput Sci 2021, 181, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddoud, M.Y.; Onjewu, A.-K.E.; Nowiński, W.; Jones, P. The determinants of SMEs’ export entry: A systematic review of the literature. J Bus Res 2021, 125, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Lima, P.F.; Crema, M.; Verbano, C. Risk management in SMEs: A systematic literature review and future directions. European Management Journal 2020, 38, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardati, N.K.; ER, M. The Impact of Social Media Usage on the Sales Process in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs): A Systematic Literature Review. Procedia Comput Sci 2019, 161, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.C.; Vivaldini, M.; de Oliveira, O.J. Production and supply-chain as the basis for SMEs’ environmental management development: A systematic literature review. J Clean Prod 2020, 273, 123141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M. Innovation capability in SMEs: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2020, 5, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, R.; Harms, J.; Liket, K.; Maas, K. Small Firms, large Impact? A systematic review of the SME Finance Literature. World Dev 2017, 97, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Soares, A.L.; de Sousa, J.P. Information, knowledge and collaboration management in the internationalisation of SMEs: A systematic literature review. Int J Inf Manage 2016, 36, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Pacheco, D.A.; Caten, C.S.T.; Jung, C.F.; Navas, H.V.G.; Cruz-Machado, V.A. Eco-innovation determinants in manufacturing SMEs from emerging markets: Systematic literature review and challenges. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 2018, 48, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, M.; Wangtueai, S.; Sharafuddin, M.A.; Chaichana, T. The Precipitative Effects of Pandemic on Open Innovation of SMEs: A Scientometrics and Systematic Review of Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2022, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, N.; Khan, Z.; Meyer, M.; Laker, B. International entrepreneurial behavior of internationalizing African SMEs – Towards a new research agenda. J Bus Res 2023, 154, 113367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovini, C.; Ossola, G.; Britzelmaier, B. How to reconsider risk management in SMEs? An Advanced, Reasoned and Organised Literature Review. European Management Journal 2021, 39, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zide, O.; Jokonya, O. Factors affecting the adoption of Data Management as a Service (DMaaS) in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Procedia Comput Sci 2022, 196, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, C.; Teuteberg, F.; Griese, K.-M.; Topi, C. The relationship between organizational culture, sustainability, and digitalization in SMEs: A systematic review. J Clean Prod 2020, 275, 122944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, N.; Al-Tabbaa, O. Inter-organizational collaboration and SMEs’ innovation: A systematic review and future research directions. Scandinavian Journal of Management 2020, 36, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epede, M.B.; Wang, D. Global value chain linkages: An integrative review of the opportunities and challenges for SMEs in developing countries. International Business Review 2022, 31, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooss, O.F.; Presser, M.; Tambo, T. Surround yourself with your betters: Recommendations for adopting Industry 4.0 technologies in SMEs. Digital Business 2022, 2, 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, J.; Fraanje, R.; Limonard, S.; Zijderveld, M. Lessons-learnt on articulating and evaluating I4.0 developments at SME manufacturing companies. Procedia Comput Sci 2023, 217, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, V.; da Rocha, A.B.; Rangel, B.; Alves, J.L. Design Management and the SME Product Development Process: A Bibliometric Analysis and Review. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2021, 7, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyanto, F.X. Peningkatan Daya Saing Ekonomi Indonesia. Jurnal Dinamika Ekonomi & Bisnis 2004, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Subchiawan, M.; Rahmawati, D. META-ANALISIS PENELITIAN TECHNOLOGY READINESS DI INDONESIA. Jurnal Profita: Kajian Ilmu Akuntansi 2021, 9, 47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Padhyegurjar, S.; Ganeshkumar, P. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. JK Science 2013, 15, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Palupi, E.; Jayanegara, A.; Ploeger, A.; Kahl, J. Comparison of nutritional quality between conventional and organic dairy products: a meta-analysis. J Sci Food Agric 2012, 92, 2774–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.M.; et al. Effects of reduced tillage in organic farming on yield, weeds and soil carbon: Meta-analysis results from the TILMAN-ORG project. Building Organic Bridges 2014, 4, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, T.D. Wheat from chaff: Meta-analysis as quantitative literature review. Journal of economic perspectives 2001, 15, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, A.; Vignoli, D. Fertility and Women’s Employment: A Meta-analysis: Fécondité et travail des femmes: une méta-analyse. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie 2008, 24, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirca, A.H.; Yaprak, A. The use of meta-analysis in international business research: Its current status and suggestions for better practice. International Business Review 2010, 19, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naipinit, T.; Kojchavivong, S.; Kowittayakorn, V.; Sakolnakorn, T.P.N. McKinsey 7S model for supply chain management of local SMEs construction business in upper northeast region of Thailand. Asian Soc Sci 2014, 10, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, A.R.; Yahaya, J.H.; Deraman, A.; Jusoh, Y.Y. The success factors and barriers of information technology implementation in small and medium enterprises: An empirical study in Malaysia. Int J Bus Inf Syst 2016, 21, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.H.; Salleh, S.M.; Yusoff, R.Z. The role of emotional and rational trust in explaining attitudinal and behavioral loyalty: An insight into SME brands. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business 2016, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.A.; Kuivalainen, O. The effect of internal capabilities and external environment on small- and medium-sized enterprises’ international performance and the role of the foreign market scope: The case of the Malaysian halal food industry; [Der Effekt von internen Kompetenzen und dem externen Umfeld auf den internationalen Unternehmenserfolg von KMU und die Moderator-Beziehung der geografische Reichweite: der Fall der Malaysischen Halal-Lebensmittelindustrie]. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 2015, 13, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, J.L.K.; Gomez, E.T. Advancing tacit knowledge: Malaysian family SMEs in manufacturing. Asian Economic Papers 2014, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, W.M.N.B.W.M.; Al Mamun, A.; Breen, J. Strategic orientation and performance of SMEs in Malaysia. Sage Open 2017, 7, 2158244017712768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.C.; Hamazah, A.; Samah, B.A.; Ismail, I.A.; D’Silva, J.L. Rural Malay involvement in Malaysian herbal entrepreneurship. Asian Soc Sci 2014, 10, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, C.R.; Saleh, Z.; Sapiei, N.S. A Survey On Financial and Management Accounting Practices Among Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Accounting Perspectives 2008, 1, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Mohamad, O.; Omar, A.; Marimuthu, M. Technology adoption among Small and Medium Enterprises (SME’s): A research agenda. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. J 2009, 53, 943–946. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, F.; Yusuff, R.M.; Zulkifli, N. Barriers to Advanced Manufacturing Technology in small-medium enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. in 2nd International Symposium on Technology Management and Emerging Technologies, ISTMET 2015 - Proceeding, 2015, pp. 412–416. [CrossRef]

- Murni, T. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation to Low Cost Strategy, Differentiation Strategy, Sustainable Innovation and Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (Studies at Batik Small and Medium Enterprises in East Java Province, Indonesia). European Journal of Business and Management 2017, 9, 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hasyim, S. Isolating mechanism as a mean to improve performance of SMEs. European Research Studies Journal 2017, 20, 594–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitabutr, V.; Pimdee, P. Thai Entrepreneur and Community-Based Enterprises’ OTOP Branded Handicraft Export Performance: A SEM Analysis. Sage Open 2017, 7, 2158244016684911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L. Perceptions of leadership competencies and the acquisition of them by CEOs in vietnamese small enterprises. Asian Soc Sci 2015, 11, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, J.C.N.; Chua, A.Y.K. The peculiarities of knowledge management processes in SMEs: The case of Singapore. Journal of Knowledge Management 2013, 17, 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirgiatmo, Y. Analysis of the potential use of social networking for the success of strategic business planning in small and medium-sized enterprises. Mediterr J Soc Sci 2015, 6, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeng, S.K.; Osman, A.; Haji-Othman, Y.; Safizal, M. E-commerce adoption among small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Northern state of Malaysia. Mediterr J Soc Sci 2015, 6, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.; Omar, N.A. Exploring the effect of Internet marketing orientation, Learning Orientation and Market Orientation on innovativeness and performance: SME (exporters) perspectives. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2013, 14, S257–S278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, D.T.P.; Khoi, N.V. Vietnamese small and medium-sized enterprises: Legal and economic issues of development at modern stage. Economic Annals-XXI 2017, 165, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, S.H.; Ashhari, Z.M. Issues and challenges of microcredit programmes in Malaysia. Asian Soc Sci 2015, 11, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrak, B.B.; Gharleghi, B.; Fah, B.C.Y.; Tan, M. Critical success factors affecting Malaysia’ SMEs through inward FDI: Case of service sector. Asian Soc Sci 2014, 10, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suroso, A.; Anggraeni, A.I. Optimizing SMEs’ business performance through human capital management. European Research Studies Journal 2017, 20, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadhilah, M. Strategic implementation of environmentally friendly innovation of small and medium-sized enterprises in Indonesia. European Research Studies Journal 2017, 20, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisip, I.A.; Harun, A. Antecedents and outcomes of brand management from the perspective of Resource based view (RBV) theory. Mediterr J Soc Sci 2013, 4, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na-Nan, K.; Ngudgratoke, S. Relationship among personality, transformational leadership, percerived organizational support, expatriate adjustment, and expatriate performance. International Journal of Business and Administrative Studies 2017, 3, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Le Ng, X.; Choi, S.L.; Soehod, K. The effects of servant leadership on employee’s job withdrawal intention. Asian Soc Sci 2016, 12, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, K.Y.; Osman, A.; Salahuddin, S.N.; Abdullah, S.; Lim, Y.J.; Sim, C.L. Relative advantage and competitive pressure towards implementation of e-commerce: Overview of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Procedia Economics and Finance 2016, 35, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueasangkomsate, P. Adoption e-commerce for export market of small and medium enterprises in Thailand. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2015, 207, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.C.; Liang, T.W.; Meng, T.T.; Chan, B. The key success factors, distinctive capabilities, and strategic thrusts of top SMEs in Singapore. J Bus Res 2001, 51, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullayaphut, P.; Untachai, S. Development the measurement of human resource competency in SMEs in upper northeastern region of Thailand. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 2013, 88, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Country | Key Success |

|---|---|---|

| (Hossain, et. al., 2022) | Bangladesh |

|

| [15] | Global |

|

| [16] | Australia, Canada, Finland, Italy, Japan, Germany, Spain, US and the UK. China, India, Russia, Brazil, Algeria, Syria, Bulgaria, Tunisia and Turkey, Subsaharan Africa with Ghana |

|

| (Ferreira de Araújo Lima, et. al., 2020) | Europe |

|

| [18] | Global |

|

| (Machado, et.al., 2020) | Global |

|

| [20] | Global |

|

| [21] | Global |

|

| (Costa, et. al., 2016) | Global |

|

| [23] | Brazil |

|

| [24] | Global |

|

| [25] | Africa |

|

| (Crovini, et. al., 2021) | Global |

|

| [27] | Global |

|

| [28] | Global |

|

| [29] | Europe, Australia, the USA, China, Korea, Taiwan, Turkey, India, and Iran |

|

| [30] | Developing countries |

|

| (Grooss, et. al., 2022) | Global |

|

| [32] | Netherlands |

|

| [33] | Global |

|

| Key Success Factor | Industry | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Sector | Manufacture | Service | |

| Ecommerce, technology, and social media | √ | √ | √ |

| International oriented | √ | √ | √ |

| Good management system | √ | √ | √ |

| Government support | √ | √ | √ |

| Working condition/ environment | √ | √ | √ |

| Financial/ Fund support | √ | ||

| Skill and competency labour/ owner | √ | √ | √ |

| Market penetration/ selection | √ | √ | √ |

| Policy | √ | √ | √ |

| Innovation | √ | √ | |

| Creativity | √ | ||

| Organizational performance and characteristics | √ | √ | √ |

| Networking with government/ supplier/ customer | √ | √ | √ |

| Leadership | √ | √ | √ |

| Planned/ Strategy (business/ market/ operational/ organizational) | √ | √ | √ |

| Branding product/ name | √ | ||

| Packaging | √ | ||

| Quality product | √ | ||

| Motivation | √ | ||

| Product development | √ | ||

| Organizational readiness | √ | √ | √ |

| Key Success Factor | Countries | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Income Country | Middle-Income Country | Low-Income Country | |

| Ecommerce, technology, and social media | Singapore | Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia | |

| International oriented | Singapore | ||

| Good management system | Singapore | ||

| Government support | Singapore | ||

| Working condition/ environment | Vietnam, Malaysia | ||

| Financial/ Fund support | Singapore | Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia | |

| Skill and competency labour/ owner | Singapore | Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia | |

| Market penetration/ selection | Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia | Cambodia, Laos | |

| Policy | Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam | Laos | |

| Innovation | Singapore | Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia | |

| Creativity | Malaysia | ||

| Organizational performance and characteristics | Malaysia, Thailand | ||

| Networking with government/ supplier/ customer | Singapore | Malaysia, Thailand | |

| Leadership | Malaysia | ||

| Planned/ Strategy (business/ market/ operational/ organizational) | Malaysia | ||

| Branding product/ name | Malaysia, Indonesia | ||

| Packaging | Malaysia | ||

| Quality product | Singapore | Thailand, Indonesia | |

| Motivation | Cambodia, Laos | ||

| Product development | Malaysia | ||

| Organizational readiness | Singapore | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).