1. Introduction

Depression and anxiety are among the most common mental health concerns worldwide [

1]. As is often remarked, with the availability of evidence-based digital mental health interventions such as transdiagnostic Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (ICBT) e.g., [

2,

3], help is just a click away. Yet a significant gap exists between those who have access to and use these services. For example, a recent analysis of ICBT utilization trends over six years (i.e., 2013-2019) in an online clinic in Saskatchewan, Canada showed that there was consistently lower (~10% compared to the expected population of ~32%) participation in ICBT among self-identified non-White/Caucasian people [

4]. People of Diverse Ethnocultural Backgrounds (PDEGs (For the lack of better terminology, we have used the phrase People of Diverse Ethnocultural Groups (PDEGs) to refer to all but self-identified Caucasian/White people in this study. In this regard, PDEGs encompass Indigenous Canadians as well as “visible minorities" or "racialized minorities" such as black, Asian, and Latin American. Other terms for this group that are used in the literature include visible monitories, racialized minorities, or Black, Indigenous People of Colour (BIPOC).)) other than White/Caucasian are known to underutilize mental health services e.g., [

5], and are also underrepresented in clinical trials of psychological interventions including ICBT [

6,

7]. Furthermore, despite the recognition of the salience of ethnocultural backgrounds on mental health e.g., [

8,

9], there has been limited research on adapting ICBT to be appropriate for multiple ethnocultural groups with the aim of improving its utilization by PDEGs in routine care settings [

10].

To address this research gap as well as to increase the use of ICBT by PDEGs in an online routine care clinic in Saskatchewan, Canada, we conducted a multi-phase patient-oriented research see [

11] project and adapted an evidence-based ICBT program based on feedback from self-identified PDEG patients, community representatives providing services to PDEGs, and ICBT clinicians see [

12] for details. Suggestions for improvement included acknowledging the role of culture on mental health and mental health stigma in the course materials, diversifying case stories, examples and images, simplifying language and adding audiovisual materials but did not involve modifying the cognitive behavioural approach. Moreover, clinicians were offered further training and efforts were made to improve community outreach see [

12]. This approach to adaptation is aligned with the Selective and Directed Treatment Adaptation Framework SDTAF; [

13,

14], which has a strong emerging evidence base to guide adaptations of Western psychological interventions for other populations. The current pilot study was conducted to assess the effectiveness, satisfaction, and engagement of PDEGS in the adapted ICBT. Given the changes made, we expected similar effect sizes, but increased engagement and satisfaction with the adapted ICBT when benchmarked against a sample of PDEGs drawn from data from the previous non-adapted version of the ICBT program see [

15].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

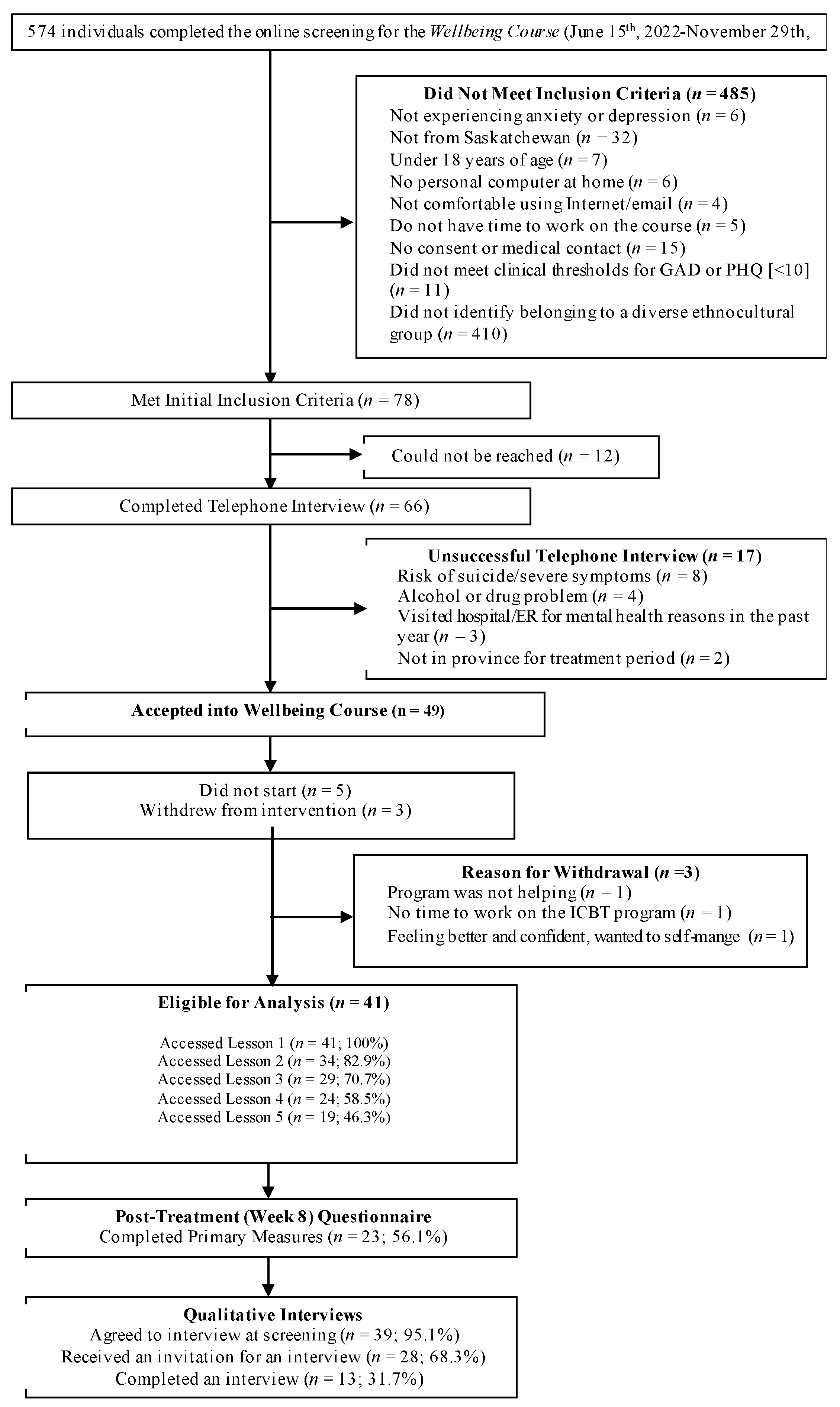

This registered pilot interventional trial (NCT05523492;

https://beta.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05523492) used a single-group pre- to post-treatment design. All eligible PDEG (N=41) who enrolled in ICBT at the Online Therapy Unit (

www.onlinetherapyuser.ca) between June 2022 and November 2022 were included (see

Figure 1). Sub-sample (e.g., self-identified non-White/Caucasian) data (N=134) collected between December 2021 and May 2022 at the same site with an equivalent protocol as part of regular service delivery were used as a benchmarking sample see [

15]. At post-treatment, ~32% (n=13) consenting participants in the pilot study were interviewed asking about their expectations and experience with the adapted ICBT Wellbeing Course and for suggestions for further improvement.

2.2. ICBT program: The Wellbeing Course

Participants were enrolled in the Adapted Wellbeing Course. This transdiagnostic course originally developed by Titov, Dear [

16] addresses both depression and anxiety and was adapted as described above for PDEGs. To access the course, patients completed an online questionnaire followed by a telephone interview. The Course includes five online psychoeducational lessons completed over ~ 8 weeks with once-weekly therapist emails or telephone calls that answer patients’ questions about the course and provide guidance on the use of skills. Each lesson includes a brief video, educational materials, case stories, homework suggestions and frequently asked questions along with additional reading if clients are interested. Weekly automated email reminders are sent to remind patients of the Course see [

16] for details.

2.3. Measures

Data were self-reported. Demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, etc.) were recorded at pre-treatment. Considering vast diversity in ethnocultural backgrounds of patients in the Canadian context [

17], ethnicity was assessed using broadly used ethno-racial categories, that is, black, white, Asian (east, middle east, south), Indigenous ( First Nations, Inuit, Métis), Latin American, and other (with the option for participants to describe their ethnicity). Patients completed measures of depression [Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9]], [

18] and anxiety [Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7]; ] [

19] at pre-treatment (baseline), each week for seven weeks, and post-treatment (end of week 8). Scores ≥10 in these measures indicate clinically significant symptoms of depression or generalized anxiety. Cronbach’s α in this study was between .66 and .91, and .81 and .93 for PHQ-9 and GAD-7, respectively. ICBT engagement was assessed using number of patient messages, phone calls, and lessons accessed. For treatment satisfaction, at post-treatment, participants answered yes/no items about whether they would recommend the treatment to a friend, and if the course was worth their time. Participants also rated satisfaction with the program, materials, and confidence to manage symptoms, and motivation to seek future treatment (1 to 5 scale). The post-treatment qualitative interviews included 12 open-ended questions about the patient’s experience with the program, including perceived cultural relevance of different aspects of the ICBT program, and ways to improve accessibility and utilization of the program for PDEGs see [

12] for details.

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28.0). Descriptive statistics described patients’ characteristics. Pilot versus benchmark groups were compared on pre-treatment characteristics, engagement and satisfaction measures using Chi square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. A series of mixed model analyses were conducted using all data available across the nine weekly assessments to examine changes in the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 outcomes over time and determine if these changes differed between groups. For each outcome, a series of models involving fixed and random effects of intercept and slope (time) were conducted. The fixed-effect models included time, group, and their interaction (time × group). Intraclass correlation coefficients were used to determine if mixed-model analyses were appropriate [

20]. Various within-individual covariance structures (e.g., scaled identity, diagonal, autoregressive [AR(1)]) were also tested. The models with smallest Akaike’s Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion were selected for the final analysis. Estimates were calculated using the full information maximum likelihood method. These analyses were conducted twice, 1) using an intention-to-treat (ITT) sample, for which data were imputed using the Multiple Imputation method such that all enrolled participants were included, and 2) using a complete case analysis, for which unimputed data were used. For the ITT analyses, twenty multiply imputed data sets were created [

21]. Since mixed-model analysis with maximum likelihood method of estimation can handle missing data, imputation prior to analysis was not necessary for complete case analysis [

22,

23]. Pre- to post-treatment effect sizes (Cohen’s

d) were computed using estimated means and standard deviations from the mixed model analysis. Further, we compared the groups on reliable change by calculating the percentage of participants who recovered (GAD-7 or PHQ-9 ≤ 4), improved reliably (GAD-7 or PHQ-9 ≤ 9), or did not show reliable improvement (GAD-7 or PHQ-9 ≥ 10). Pre-treatment standard deviations and test-retest reliability estimates α = .84 for PHQ-9 [

18] and α = .83 for GAD-7 [

19] were used to compute reliable change index [

24].

The digitally recorded post-treatment qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim, coded by combining deductive and inductive approaches, and organised according to themes for thematic analysis [

25]. The frequency of each code was recorded for descriptive analysis. The semi-structured interview data were coded by a researcher (EV) using NVivo (version 12 Plus) software (

https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home).

3. Results

A total of 41 participants from the pilot study (see

Figure 1 for the participant flow chart) and 134 participants from the benchmarking study were included (see

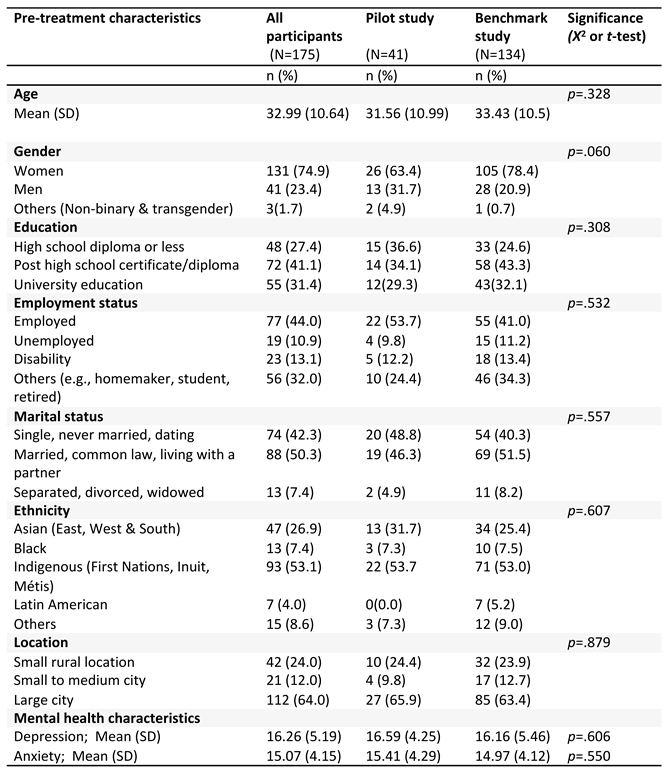

Table 1 for pre-treatment demographic and clinical characteristics for the groups). No group differences were found (see

Table 1). Participants were mostly Indigenous (53.1%), women (74.9%), married (50.3%), with an average age of 32.9 years (SD = 10.6 years) residing in large cities (64%).

3.1. Missing data

For both groups, there were no missing data across pre-treatment demographic and clinical variables but there were 55 (41.0%) and 17 (41.5%) missing values in the benchmark and pilot samples, respectively, at post-treatment. In both groups, data were missing mainly due to dropout. There were no statistically significant differences in pre-treatment demographics, and anxiety and depression symptom severity between the dropouts and completers, therefore the data were assumed to be missing at random [

26].

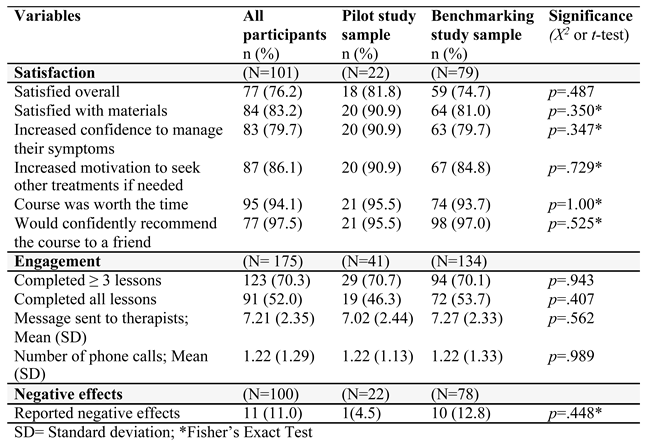

3.2. Satisfaction

Although a slightly higher percentage of pilot study participants reported satisfaction on most variables, there were no statistically significant differences between pilot and benchmark groups on satisfaction variables (see

Table 2).

3.3. Engagement

There were no significant differences in attrition between pilot (41.5%) and benchmark (41.0%) groups on post-treatment outcome variables (p = .55) or mean number of lessons completed (pilot: 3.78 (SD = 1.79) vs benchmark: 3.99 (SD = 1.74), p = .47). Also, the groups did not significantly differ on the mean number of messages and phone calls to therapists (see

Table 2).

3.4. Effectiveness

As expected, ITT analysis yielded a non-significant interaction effect for the PHQ-9 (β1 = − 0.01, 95% CI = [− 0.28, 0.21], p = .943) and the GAD-7 (β1 = − 0.13, 95% CI = [− 0.35, 0.09], p = .261). Similar results were obtained for the complete case analysis of the PHQ-9 (β1 = − 0.03, 95% CI = [− 0.29, 0.34], p = .866) and GAD-7 (β1 = -0.09, 95% CI = [− 0.41, 0.22], p = .553), suggesting that the change in self-reported depression and generalized anxiety symptoms over 9 weeks was not significantly different between groups (see

Figure 2). For both groups, significant reductions on the PHQ-9 (β1 = − 0.82, 95% CI = [− 1.01, − 0.64], p < .001) and GAD-7 (β1 = − 0.79, 95% CI = [− 0.94, − 0.65], p < .001) were observed over time in ITT analyses as well as in the complete case analyses, PHQ-9 (β1 = − 0.91, 95% CI = [− 1.06, − 0.57], p < .001) and GAD-7 (β1 = − 0.80, 95% CI = [− 0.95, − 0.64], p < .001). Final models used AR (1) within-individual covariance structure. Similar large pre-to-post within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were found for the PHQ-9 in the pilot (d = 1.23, 95% CI [0.68, 1.77]) and benchmark (d = 1.18, 95% CI [0.88, 1.48]) groups and for the GAD-7 pilot (d = 1.24, 95% CI [0.69, 1.79]) and benchmark (d = 1.27, 95% CI [0.97, 1.58]) groups.

3.5. Clinically significant change

On the PHQ-9 at post-treatment, for the pilot group (n=24), 10 (41.7%), 4 (16.7%), and 10 (41.7%) met criteria for recovered, reliable improvement, and did not improve reliably, respectively. In the benchmark group (n=79), 27 (34.2%), 19 (24.1%), and 33 (41.8%), met criteria for recovered, reliable improvement, and did not improve reliably, respectively, on the PHQ-9. Similarly, on the GAD-7, in the pilot group (n=24), 8 (33.3%), 6 (25.0%), and 10 (41.7%) met criteria for recovered, reliable improvement, and did not improve reliably, respectively. In the benchmark group (n=79), 28 (35.4%), 20 (25.3%), and 31 (39.2%) met criteria for recovered, reliable improvement, and did not improve reliably, respectively.

3.6. Negative effects

One (2.4%) pilot study participant and 11 (8.2%) benchmark study participants self-reported negative effects during the treatment period. In both groups, negative effects were related to transient increases in symptoms during ICBT, such as when confronting bad memories, when challenging thoughts, or thinking about symptoms.

3.7. Post-treatment interviews

Thirteen self-identified PDEG participants representing Indigenous (53.8%), Asian (23.1%) and Black (23.1%) communities were interviewed. There were an equal number of self-identified men and women (n=6, 46.2% each) and one (7.7 %) transgender participants, with an average age of 31 years (SD = 11.4 years).

Most of the interview participants (n=12, 92.3%) indicated that the ICBT program met or exceeded their expectations and reported positive experiences with the therapists. Likewise, in terms of cultural fit of the ICBT program, a majority (n=10, 76.9%) said the program aligns with their cultural beliefs and practices. When asked for suggestions for specific improvements to make the program better for people from their ethnocultural background, seven (53.8%) participants mentioned there was no need for change in the program. The remaining (n=6, 46.2%) participants provided some suggestions for further improvements: making more public aware of this freely available program (n=2, 15.4%), adding culture-specific content (n=2, 15.4%), diversifying the cultural background of the main characters represented in the program (n=2, 15.4%), language translation (n=1, 7.7%), and increasing therapist support (n=1, 7.7%).

4. Discussion

We examined the treatment engagement, satisfaction, and outcomes of an ICBT program adapted for PDEGs benchmarked against a standard (non-adapted) ICBT program completed by PDEGs. The results showed that there were no statistically significant differences in clinical outcomes, engagement and satisfaction between the pilot and benchmark samples, which may reflect the sample size and comparison of the adapted ICBT program to an already established and effective ICBT program. It is unclear at this point whether further adaptations to the ICBT program would enhance the outcomes, engagement and satisfaction above and beyond the standard ICBT program. Post-treatment interviews revealed patients were largely satisfied with the adapted program and there was little consensus on recommendations for improvement suggesting further adaptations may not result in significant benefit and the current outcomes may reflect the maximal benefits with this program.

While statistically significant differences were not observed, some non-measured benefits have yet to be examined, including whether offering this adapted ICBT course will improve uptake of the course by PDEGs. Further, although this study did not provide strong evidence that patient-oriented adaptation of the ICBT improves engagement, satifsfaction and clinical outcomes, engaging PDEGs and other groups who work with PDEGs has provided some assurance that the adapted ICBT program is culturally relevant and clinically significant in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression across diverse ethnocultural groups.

Of note, although we could not conduct more detailed ethnocultural subgroup analyses (e.g., Asian group includes many diverse ethnicities and cultures) due to small sample size in our pilot study, past research e.g., [

27,

28] shows that younger adults tend to engage less and drop-out more from the ICBT program. Further, there is some evidence that younger immigrants likely acculturate faster see [

29,

30] and more acculturated people are less likely to benefit from culturally-adapted interventions than less acculturated people [

31]. In the current study, the mean age of the participants was 31.6 (SD=10.9) (see

Table 1), which was lower than in our previous studies (Mean age = 38.14, SD = 11.9 years) see [

4]. Further, consistent with the literature, engagement was measured using number of lessons completed and email and/or telephone exchange with therapists. However, although these measures are useful in assessing behavioural aspects of engagement, they do not necessarily reflect the level of engagement (e.g., effort put into reviewing the lessons, practicing skills, continuity in use of the learned skills) with the program. All these factors may have influenced the rate of engagement and effectiveness of the adapted intervention in the current study. Further studies should consider involving individuals from diverse age groups and more nuanced measures of engagement see [

32].

Within a setting that includes PDEGs, limited organizational resources do not allow for the development of ICBT for each ethnocultural group accessing services. Nevertheless, adaptation to specific larger groups could be helpful such as Indigenous peoples using Indigenous research methods as has been done in Australia see [

33]. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that interventions targeted to specific ethnocultural group are more effective than interventions adapted for multicultural settings [

31]. However, non-adapted ICBT interventions have also been demonstrated to produce equivalent outcomes in migrants and non-migrants in Australia [

34] and elsewhere see [

35]. We opted for a patient-oriented adaptation as it was not feasible (based on available resources) for us to conduct a comprehensive cultural adaptation of the ICBT program considering ICBT is being implemented in a multicultural routine care setting in Saskatchewan. Therefore, a thought for future studies remains, that is, as the existing research suggests e.g., [

36], perhaps we would get better engagement, satisfaction, and treatment outcomes had the ICBT program been culturally adapted and tailored to specific ethnocultural groups. Therefore, the findings of this study are preliminary and should not diminish the importance of need-informed cultural adaption, especially targeting a specific ethnocultural group in the context of digital mental health.

Author Contributions

R.P.S. and H.D.H. conceptualized the study and acquired the funding; R.P.S., E.V., and H.D.H. wrote the original draft of the manuscript and B.F.D and N.T. provided important revisions. R.P.S. performed the statistical analyses. H.D.H. provided supervision and guidance on data analysis. All authors contributed to investigation and interpretation of results. All authors read, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation and Mental Health Research Canada funded the research. The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health funds the Online Therapy Unit to deliver Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy to residents of Saskatchewan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Regina approved the benchmark study (REB # 2019-197; December 12, 2019) and the pilot trial (REB # 2022-012; March 17, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all research participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in the study are available from the Online Therapy Unit (

www.onlinetherapyuser.ca) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and community stakeholders associated with the project. We would specifically like to acknowledge our working group members including, Vanessa Heron, Lee Bourgeault, Basmah Almosallem, Vibya Natana, Micha Kasongo, Belinda Owusu Nyamike, Arjun Adhikari for their inputs and guidance in research and the Course modification, and all therapists, Kelly Adlam, Aaron Ingrouville, Janet Tzupa, MacKenzie-Martin-Proskie, Katherine-Owens, who provided ICBT to patients in this trial. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Marcie Nugent the Online Therapy Unit Operations Director and University of Regina Research IT Support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Titov, N.; Dear, B.; Nielssen, O.; Staples, L.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Nugent, M.; et al. ICBT in routine care: A descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018, 13, 108–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedman-Lagerlöf, E.; Carlbring, P.; Svärdman, F.; Riper, H.; Cuijpers, P.; Andersson, G. Therapist-supported Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy yields similar effects as face-to-face therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 305-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Peynenburg, V.; Thiessen, D.L.; Nugent, M.; Karin, E.; Staples, L.; et al. Utilization, patient characteristics, and longitudinal improvements among patients from a provincially funded transdiagnostic internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy program: observational study of trends over 6 years. Can. J. Psychiatry 2022, 67, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, B. L.; Trinh, N.-H.; Li, Z.; Hou, S. S.-Y.; Progovac, A. M. Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo, A. J.; Makol, B. A.; Castro, A. S.; Colón-Quintana, N.; Wagstaff, A. E.; Guo, S. Diversity in randomized clinical trials of depression: A 36-year review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 67, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jesús-Romero, R.; Holder-Dixon, A.; Lorenzo-Luaces, L. Reporting and representation of racial and ethnic diversity in randomized controlled trials of internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (iCBT) for depression. PsyArXiv Pre-print, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Gupta, S.; Bhui, K.; Craig, T.; Dogra, N.; Ingleby, J. D.; Kirkbride, J.; Moussaoui, D.; Nazroo, J.; Qureshi, A. WPA guidance on mental health and mental health care in migrants. World Psychiatry 2011, 10, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis-Fernández, R.; Kirmayer, L.J. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: Understanding symptom experience and expression in context. Transcult. Psychiatry 2019, 56, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.; Benson, N. M.; Myrick, K.; Eysenbach, G. Focusing on Digital Research Priorities for Advancing the Access and Quality of Mental Health. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e47898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for patient-oriented research: patient engagement framework; Canadian Institutes of Health Research: 2014.

- Sapkota, R. P.; Valli, E.; Wilhelms, A.; Adlam, K.; Bourgeault, L.; Heron, V.; Dickerson, K.; Nugent, M.; Hadjistavropoulos, H. D. Patient-Oriented Research to Improve Internet-delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for People of Diverse Ethnocultural Groups in Routine Practice. Preprints.org 2023, 2023051904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.S. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clin. Psychol.: Sci. Pract. 2006, 13, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, K.; Yeh, M.; Lau, A.; Argote, C. B. Parent-child interaction therapy for Mexican Americans: Results of a pilot randomized clinical trial at follow-up. Behav. Ther. 2012, 43, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peynenburg, V.; Sapkota, R. P.; Lozinski, T.; Sundström, C.; Wilhelms, A.; Titov, N.; Dear, B.; Hadjistavropoulos, H. The Impacts of a Psychoeducational Alcohol Resource During Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression and Anxiety: Observational Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e44722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titov, N.; Dear, B. F.; Staples, L. G.; Bennett-Levy, J.; Klein, B.; Rapee, R. M.; Shann, C.; Richards, D.; Andersson, G.; Ritterband, L. MindSpot clinic: an accessible, efficient, and effective online treatment service for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity; Statistics Canada: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026b-eng.pdf?st=v070_cQJ, 2022.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. L.; Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R. L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J. B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peugh, J. L.; Enders, C. K. Using the SPSS mixed procedure to fit cross-sectional and longitudinal multilevel models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2005, 65, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. W.; Olchowski, A. E.; Gilreath, T. D. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev. Sci. 2007, 8, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twisk, J.; de Boer, M.; de Vente, W.; Heymans, M. Multiple imputation of missing values was not necessary before performing a longitudinal mixed-model analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.; Davison, M. L.; Long, J. D. Maximum likelihood versus multiple imputation for missing data in small longitudinal samples with nonnormality. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 426–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, N. S.; Truax, P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991, 59, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, R. J.; Rubin, D. B. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2002.

- Sapkota, R. P.; Peynenburg, V.; Dear, B. F.; Titov, N.; Hadjistavropoulos, H. D. Engagement with homework in an Internet-delivered therapy predicts reduced anxiety and depression symptoms: A latent growth curve analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 91, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, M.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Schneider, L.; Dear, B.; Titov, N. Who benefits most from therapist-assisted internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy in clinical practice? Predictors of symptom change and dropout. J Anxiety Disord 2018, 54, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, B. Y.; Chudek, M.; Heine, S. J. Evidence for a sensitive period for acculturation: Younger immigrants report acculturating at a faster rate. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, H. D. The acculturation processes: The strategies and factors affecting the degree of acculturation. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2011, 23, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griner, D.; Smith, T. B. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychother.: Theory Res. Pract.Training 2006, 43, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torous, J.; Michalak, E. E.; O’Brien, H. L. Digital health and engagement—looking behind the measures and methods. JAMA network open 2020, 3, e2010918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titov, N.; Schofield, C.; Staples, L.; Dear, B. F.; Nielssen, O. A comparison of Indigenous and non-Indigenous users of MindSpot: an Australian digital mental health service. Australas. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayrouz, R.; Karin, E.; Staples, L. G.; Nielssen, O.; Dear, B. F.; Titov, N. A comparison of the characteristics and treatment outcomes of migrant and Australian-born users of a national digital mental health service. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, M. E. H.; Waller, G.; Hardy, G. Cultural adaptations of cognitive behavioural therapy for Latin American patients: unexpected findings from a systematic review. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020, 13, e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D. M.; Draheim, A. A.; Anderson, P. L. Culturally adapted digital mental health interventions for ethnic/racial minorities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 90, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).