1. Introduction

Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) is a congenital condition of the enteric nervous system first described in 1886 by Harald Hirschsprung. The disordered caudal migration of neural crest cells results in a lack of intrinsic innervation (neuronal ganglion cells and enteric glial cells) in the affected intestine. Because of this lack of innervation there is unrelieved contraction of the colonic wall and inefficient or absent peristalsis which manifests as a functional intestinal obstruction [

1].

Usually, we see clinical manifestations of the disease in the first month (65%) or in the first year (95%) after birth. Most frequent manifestations are delayed passage of meconium, abdominal distention, bilious vomiting and severe constipation. In 10-25% of neonates, HD initially presents with serious complications such as Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis.

The disease is quite rare with an incidence of 1/5000 live births and a 4/1 male/female ratio [

2]. There are different forms of HD, depending on the extent of the aganglionosis: the classical short-segment form (80-85%) with aganglionosis from the anal canal up to the sigmoid, the long-segment form with aganglionosis up to the caecum, total colonic form and small or total intestinal HD with aganglionosis extending beyond the terminal ileum.

Diagnosis of the disease can be difficult, in particular in premature children. Histology is still the golden standard to diagnose HD. There are a variety of different rectal biopsy techniques: suction biopsy, punch biopsy and open biopsy. Clinical practice varies, but most practitioners obtain two to three rectal biopsy specimens per procedure to exclude inconclusive results [

3]. The specimen is sent to the pathology department immediately after biopsy. There the specimen is fresh frozen or fixed, depending on the additional histochemistry used, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) to demonstrate aganglionosis and nerve trunk hypertrophy. Ideally, one third of the specimen is submucosa. The presence of one ganglion cell excludes HD.

The heterogeneity of rectal biopsy techniques, both in surgical harvesting and pathological examination and reporting, used in our hospitals, encouraged us to compare our techniques, evaluate complications and search for a standardization in reporting the histological results in an easy-to-use format for later facilitated decision making concerning further (surgical) diagnostics and therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

We gathered the anonymous biopsy information from five hospitals (UZ Leuven, UZ Brussel, GZA Antwerpen, ZNA Antwerpen and AZ Sint-Jan Brugge/Oostende) of all patients in which rectal biopsies were taken to exclude or confirm Hirschsprung’ disease over two years (2020-2021).

2.2. Data

Information that was shared involved the type of biopsy (suction, punch or open), the age of the patient at the time of biopsy, information concerning pathology (ganglion cells, nerve hypertrophy, layer in which they were found) and the result (conclusive or not). If the biopsies were inconclusive, we registered the cause why they were inconclusive and the type of biopsy used during the second attempt. Furthermore, all adverse effects of the procedure were registered.

In cases where information was incomplete, we did not include the patient in this study.

2.3. Biopsy Techniques

2.3.1. Suction Biopsy (“Non-Surgical”)

There are a lot of techniques and devices to obtain a suction biopsy. In general (mostly depending on the age of the child being less than six months old), the patient is awake in the lithotomy position. The biopsy is taken along the posterior wall of the rectum around two centimeters above the dentate line. No anterior biopsies are taken because of the possibility of perforation into the vaginal wall or abdominal cavity.

Most biopsies are taken with the SOLO-RBT

® instrument, a modified version of the original device proposed by Noblett [

4]. This instrument is designed to be operated by one person. A pressure ranging from 0 to 760 cm H

2O is used to suck in the mucosa and a part of the submucosa. One push on the trigger cuts the sucked in tissue. Depending on the amount of tissue sampled, the pressure is adjusted for the next biopsies [

5].

Some of the biopsies are taken with the rbi2 system® (Aus Systems, Australia). The pressure can be seen on a manometer and is ideally 150 cm H2O. The device uses a lower pressure than the older systems (SOLO-RBT®), but it must be handled by two people. One person positions the instrument in the rectum, the other applies the pressure by withdrawing the plunger to three to five ml. When the trigger is pulled, the tissue that is sucked in is cut and collected in the tip of the instrument. Depending on the amount of tissue sampled, the pressure is adjusted for the next biopsies. Caution should be taken not to exceed the recommended suction pressure.

2.3.2. Punch Biopsy (“Non-Surgical”)

The punch biopsies are performed mostly without general anaesthesia, but depending on the age (under one year of age), in the lithotomy position. The biopsy is also taken along the posterior wall of the rectum. Depending on the age of the patient, varied sizes of biopsy forceps are used. With the forceps a small bite of mucosa and submucosa is taken and pulled out.

2.3.3. Open Biopsy (“Surgical”)

Open rectal biopsies are performed under general anaesthesia in the lithotomy position. An anuscope or speculum is used to have good vision on the posterior wall of the rectum. A deep biopsy with mucosa and submucosa of approximately one centimetre wide and two centimetres long is taken, starting one and a half cm above the dentate line. The mucosa is afterwards closed with separate stitches of vicryl 4/0. Mostly open biopsies are used when less invasive techniques as described above did not give conclusive results or when the child is too old to perform a biopsy without general aneasthesia.

2.4. Adverse Effects

Most adverse effects (bleeding, rectal perforation) after biopsy occur immediately after the procedure. When no major bleeding, fever or pain was present, patients were discharged after several hours of observation.

2.5. Anatomopathology

Nerve hypertrophy and the absence of ganglion cells are pathological signs for the diagnosis of HD. We can see nerve hypertrophy and ganglion cells in the Meissner and Auerbach plexus, but one of both plexuses is sufficient for the pathologist to diagnose HD. The Meissner plexus is located in the submucosa, the Auerbach plexus in the muscularis propria, between the circular and longitudinal muscle. Sometimes offshoots of the nerve hypertrophy from the Meissner plexus can be seen extending in the mucosa layer (lamina propria) on additional histochemistry, and this is increasing with age. [

6] Depending on the pathologist, this can be enough to conclude for HD in superficial biopsies with insufficient submucosa.

Immediately after biopsy the specimen is sent to the pathology department. The specimen is fresh frozen or fixed, depending on the additional histochemistry used, and stained with HE. Additional histochemistry is used to further investigate the specimen. Depending on the hospital this may be immunohistochemistry or enzymehistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry with calretinin, S100 and synaptophysin has to be carried out on formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue and is used in four out of five hospitals. Additional enzymehistochemistry staining with acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and NADH diaphorasis has to be done on fresh frozen specimens and is used in one hospital. Calretinin (positive in control sample), S100 (positive in control sample), synaptophysin (positive in control sample) and AChE staining (negative in control sample) highlight the nerve hypertrophy while NADH diaphorasis and calretinin put the emphasis on the ganglion cells in the specimen [7-13].

The pathologist examines the sample and classifies it as conclusive or inconclusive. Conclusive means that the sample is pathological (HD) or normal. A classification of “inconclusive” means the sample is inadequate to make a clear statement about the possible underlying disease.

3. Results

In two cases the information was incomplete. We did not include the patients in this study.

All five hospitals use the open, surgical, biopsy technique. For the non-surgical biopsies, three out of five use the punch biopsy technique and three use the suction technique. With one hospital using both punch and suction biopsy technique, depending on the choice of the surgeon. In total 82 biopsies of which 20 suction (24,4%), 31 punch (37,8%) and 31 open biopsies (37,8%) were taken. The mean age at time of biopsy was 194 days old in the suction biopsy group, 830 days for punch biopsy and 682 days for open biopsy.

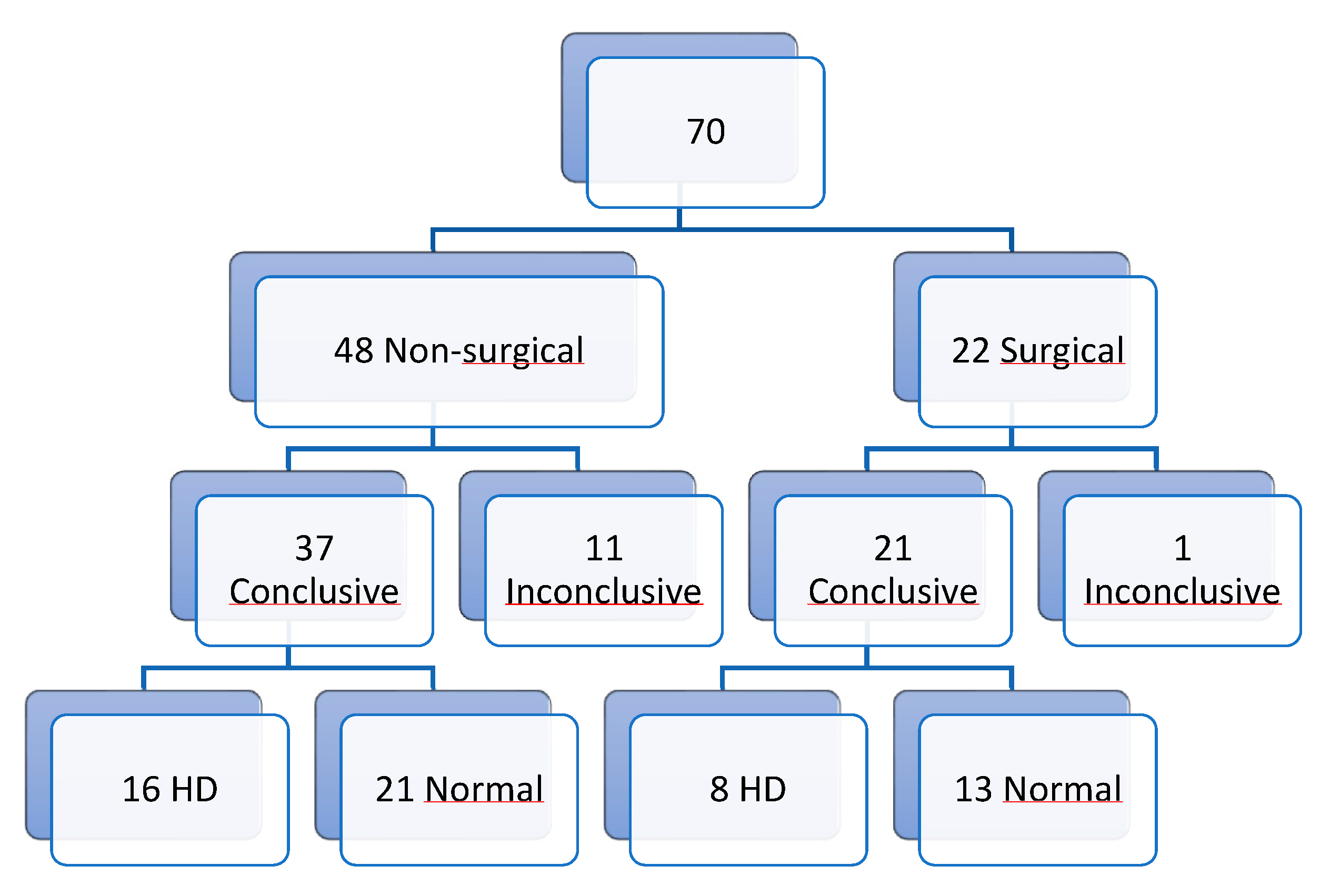

Of all biopsies, 70 were first biopsies. (

Figure 1) Of those first biopsies, 48 (68,5%) were non-surgical biopsies and 22 (31,5%) were surgical biopsies. In the non-surgical biopsy group, we report 11 inconclusive results (23%) and 37 conclusive results (77%) (16 with the diagnosis of HD (33,3%) and 21 (43,7%) normal biopsies). In the surgical biopsy group, we report 1 (4,5%) inconclusive result and 21 (95,5%) conclusive results, (8 (36,4%) results with the diagnosis of HD and 13 (59,1%) normal biopsies). The non-surgical biopsy group can be divided in 18 suction biopsies and 30 punch biopsies. Of those 18 suction biopsies, 7 (38,9%) biopsies give inconclusive results and 11 (61,1%) conclusive results. The conclusive results are divided in 5 (27,8%) biopsies with the diagnosis of HD and 6 (33,3%) normal biopsies. In the punch biopsy group, we have 4 (13,3%) inconclusive results and 26 (86,6%) conclusive, divided in 11 (36,7%) with the diagnosis of HD and 15 (50%) normal biopsies. (

Figure 2)

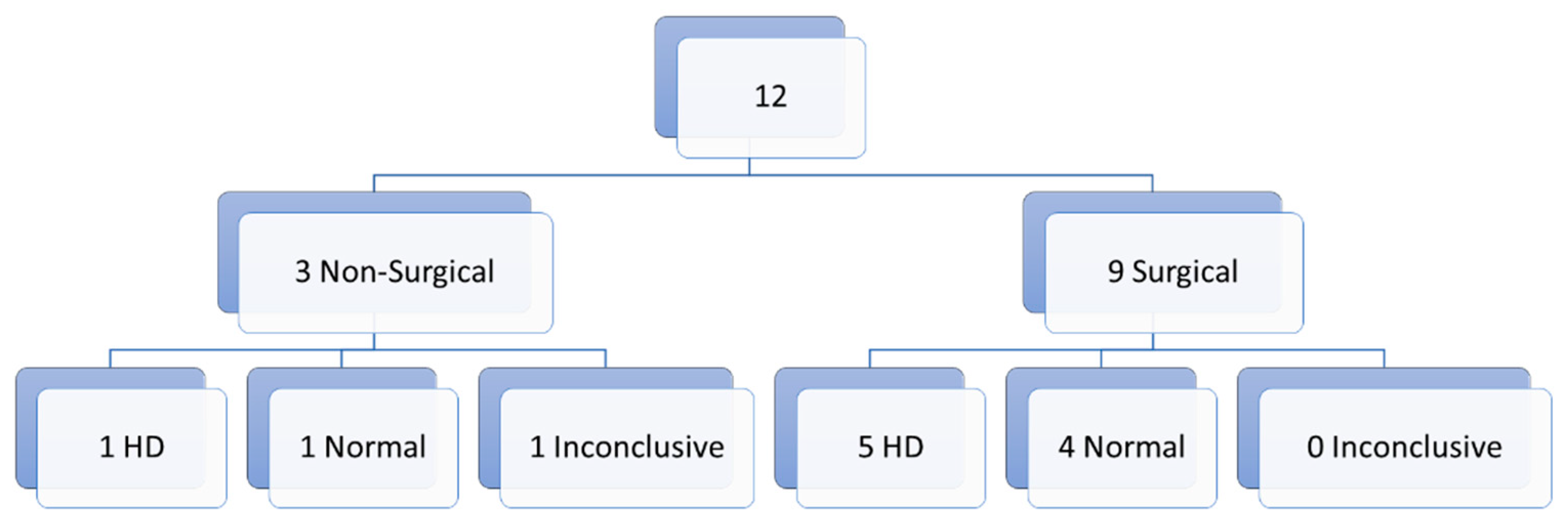

In total we have 12 inconclusive first biopsies (17,1%) for which a second biopsy was needed. Of those 12 second biopsies, 9 were surgical and 3 non-surgical biopsies. In the non-surgical biopsy group, we had 1 inconclusive result, (a suction biopsy), 1 biopsy with the diagnosis of HD (punch) and one normal biopsy (suction). In the surgical group we have 0 inconclusive results, 5 with the diagnosis of HD and 4 normal biopsies. (

Figure 3)

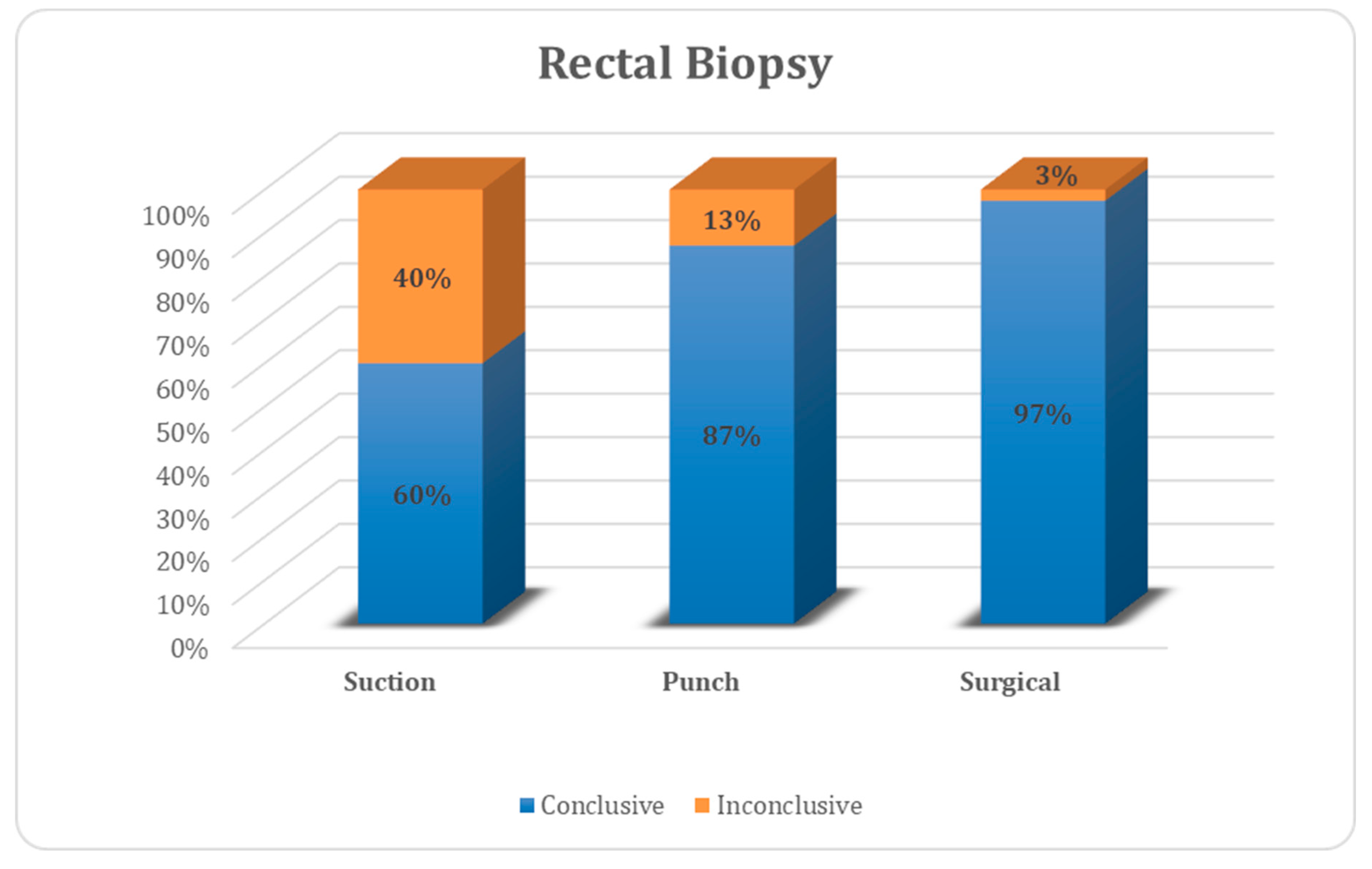

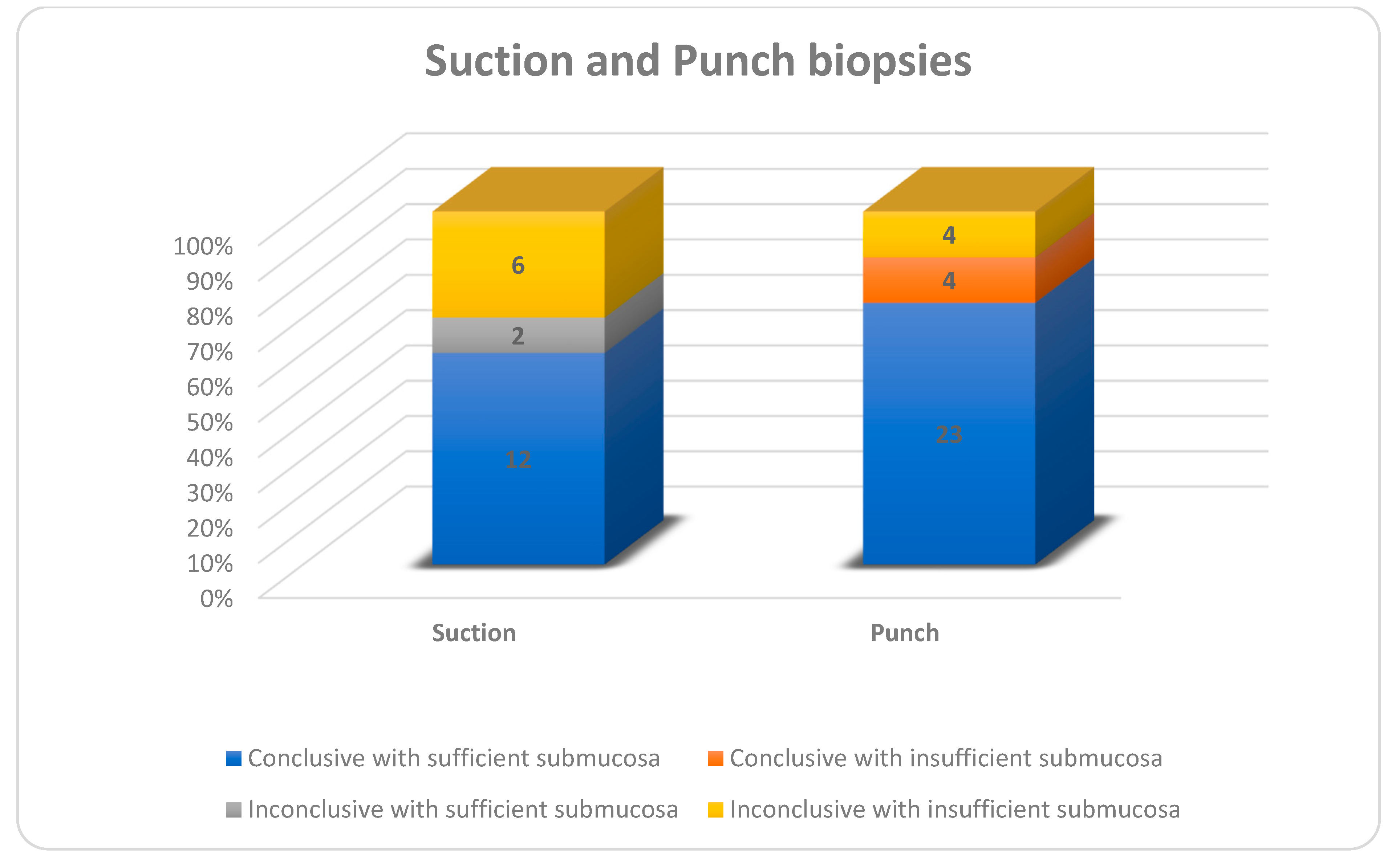

Of all biopsies 69 were conclusive (84,2%), 13 were not (15,8%). In the suction biopsy group 60% were conclusive, 40% not, for punch biopsy 87% and 13% respectively and for open biopsy 97% and 3%. (

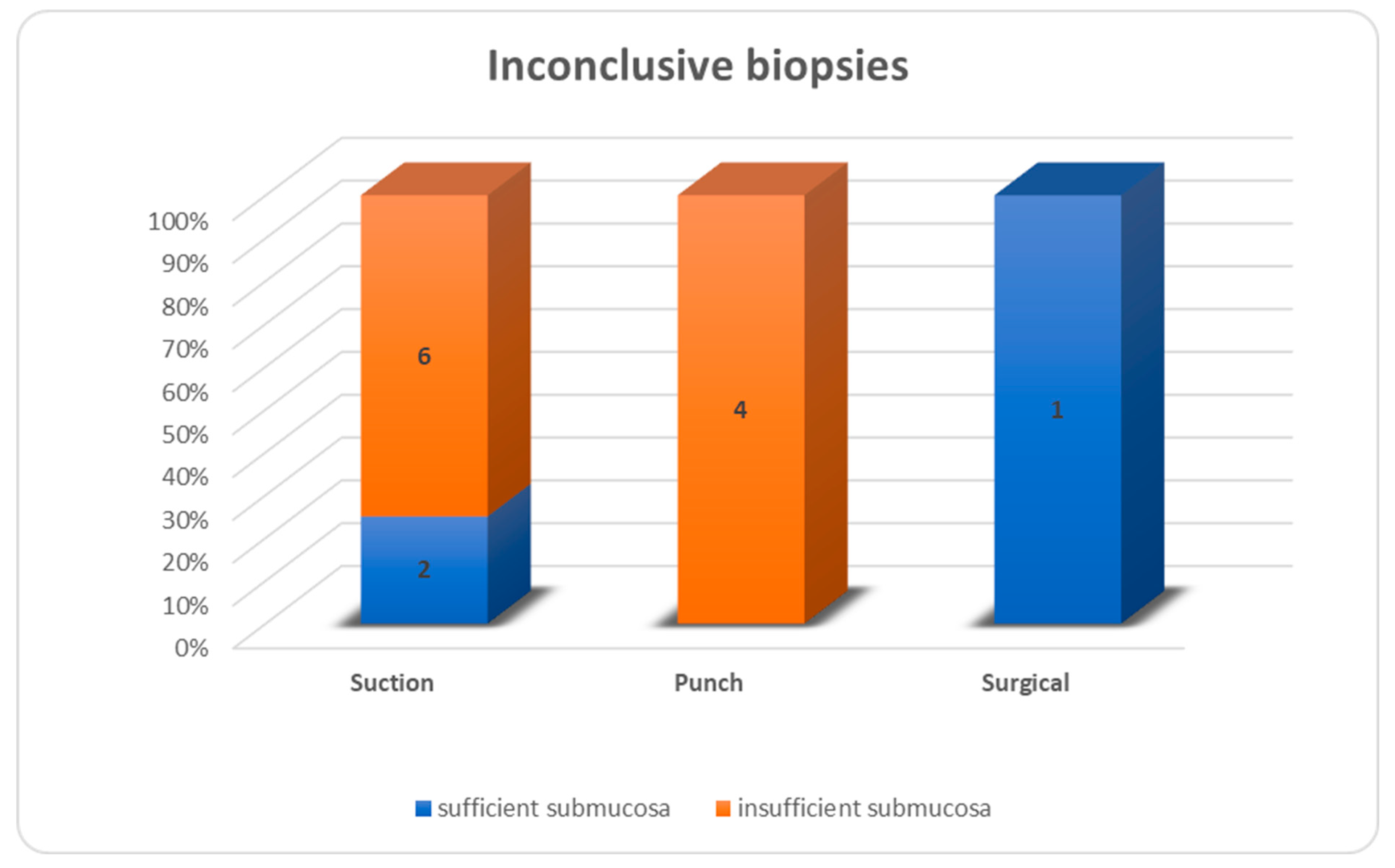

Figure 4) Inconclusive results were due to insufficient submucosa in 6/8 suction biopsies, 4/4 punch and 0/1 open biopsies. (

Figure 5) If we look at all biopsies, suction biopsies result in an insufficient amount of submucosa in 6/20 cases (30%) and punch biopsies in 8/31 cases (26%). In 4/8 cases of insufficient submucosa after punch biopsy, there was an insufficient amount of submucosa, but it was still enough to make a conclusive result. An insufficient amount of submucosa was the reason for an inconclusive result in 6/20 cases (30%) after suction biopsy and 4/31 (12,9%) after punch biopsy. (

Figure 6) We had one case with major postoperative bleeding post suction biopsy; there were no further adverse effects after biopsy.

4. Discussion

Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) is a rare disease and the golden standard for its diagnosis is a pathological confirmation by rectal biopsy. The heterogeneity of rectal biopsy techniques used in the world but also in our five centers in which we conducted our study, encouraged us to compare our techniques, evaluate complications and search for a standardization in reporting the histological results in an easy-to-use format for facilitated decision making concerning further (surgical) diagnostics and therapy.

4.1. Biopsy

In our study non-surgical biopsies are prone to give more inconclusive results. This difference can be explained by the lower amount of submucosa in the non-surgical biopsy group. This is due to the biopsy technique used, but also due to the surgeon taking the (non-surgical) biopsy and the pathologist evaluating it. Both suction (30%) and punch (26%) had around the same amount of insufficient submucosa in biopsies but not the same number of inconclusive results. It is striking that four out of eight punch biopsies with insufficient submucosa are still evaluated as conclusive and none for suction biopsies. These results are attributed only to the pathologist evaluating the biopsies and not to the biopsy technique used or the surgeon taking the biopsy, since those four conclusive punch biopsies with insufficient submucosa were performed in two hospitals. Sometimes offshoots of the nerve hypertrophy from the Meissner plexus can be seen extending in the mucosa layer (lamina propria) on additional histochemistry. Depending on the expertise of the pathologist, this can be enough to conclude for HD. Unfortunately the different types of biopsies were not evenly distributed by hospital and consequently not by pathologists. This is a clear limitation of our study. A systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Comes et al. reviewing all biopsy techniques for the diagnosis of HD, found no difference in conclusive results between suction (88%), punch (95%) and open techniques (94%) [

14]. However, they did not specify if there was sufficient amount of submucosa present in the specimens. A systematic review of the literature concerning suction biopsies for the diagnosis of HD was performed by Friedmacher et al [

15]. They reported an 89,9% adequate tissue sample of suction biopsies for the diagnosis of HD in 14,053 samples. Also, in this systematic review there was no documentation about the amount of submucosa present in the specimens. The conclusive results for suction biopsy in these two systematic reviews are clearly higher than in our small series, where only 60% of samples were conclusive (in contrast to 87% for punch biopsies).The first is probably related to surgical technique and/or pathological expertise, but the exact reason for this in our cohort is not clear at this time.

Non-surgical biopsies are biopsies that can be performed without general anaesthesia and are therefore the first choice in neonates. Open biopsy needs a general anaesthesia which is not favorable in neonates. The higher mean age in suction, but certainly in the punch biopsy group, is due to a couple of outliners with higher ages and therefore raising the mean age in this small sample group. The number of patients in each biopsy group in our study is too small to stratify the results in age groups, so we cannot make conclusions on relationship between age or prematurity and inconclusive biopsies. Green et al. however, showed a substantially and significantly higher percentage of inadequate procedures in the suction biopsy group (24,1%) in comparison with open biopsy technique (0,9%) in patients older than 6 months. The proportion of inadequate biopsies for those < 6 months was 7,6% compared to 25% in those > 6 months. Potential explanations for the increase in inadequacy seen in suction biopsies over 6 months include patient cooperation (as suction biopsies are performed unsedated, larger infants are less likely to comply with the procedure). Their findings may also be explained by the decreased density of ganglion cells in the submucosa that is seen with age. Furthermore, older children, especially those with chronic constipation, likely have a larger rectal vault, thus obtaining an adequate submucosal sample can be more difficult when performing a suction biopsy. This may necessitate larger biopsies in older children to achieve an equivalent adequate result [

16,

17].

In our study we had one complication, a postoperative bleeding in the suction group. The number of patients per biopsy technique is too small to make a conclusion about the complication rate difference between biopsy groups. It is however clear, in our study, but also in the literature that all biopsy techniques are safe to perform [

14,

15,

18]. Comes et al. demonstrated a significantly higher complication rate for punch biopsies than for suction biopsies. They attribute the difference between suction and punch to the fact that punch biopsy results in larger fragments [

14]. However the complication rates in the open biopsy group were not significantly different compared to suction or punch biopsy groups.

4.2. Anatomopathology Report

Our group gathered information out of different hospitals during this study. The amount of information concerning the pathology result was not equivalent across different hospitals, and also different depending on the pathologist writing the report. There are a few key findings that we as surgeons would like to know about our biopsy, pathology-wise, to assess our next step in the treatment of the patient. Therefore, we compiled a checklist concerning the anatomopathology rapport for diagnostic rectal biopsies for colleagues surgeons and pathologists working on HD.

The pathology report should contain:

The different layers of the rectal wall present in the biopsy

The presence of ganglion cells, the layer they are found in and the description of their pattern: regular or irregular.

The presence of hypertrophic nerve fibers, the layer or plexus they are found in, their size and the description of further growth in the lamina propria or not.

A conclusion from the pathologist: If the result is not conclusive, a short explanation on why this is not the case.

How to stain the specimen is debatable and not part of this study. Immunohistochemistry and enzymhistochemistry are feasible and can both be used to further examine the specimen. The pathologist should use the technique that he/she is the most familiar with. In general, immunohistochemistry is used on a larger scale because it is easier to work with and can be done on formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue instead of fresh frozen tissue.

5. Conclusions

Diagnostic rectal biopsies in children are safe. The obtained result (conclusive vs. inconclusive) is related to patient factors but largely to the biopsy technique used, the surgeon performing the biopsy and the pathologist evaluating the biopsy. Non-surgical biopsies are less likely to give conclusive results in comparison with surgical biopsies. Open biopsies are very useful when previous non-surgical biopsies are inconclusive. An experienced pathologist is a key factor for the result. The anatomopathology report should specify the different layers present in the specimen, the presence of ganglion cells and hypertrophic nerve fibers, their description and a conclusion.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of AZ Sint-Jan (protocol code 2917 on 07/10/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the sole purpose of improvement of quality of care, absence of any specific intervention and anonymity of patient data.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available but can be provided on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Heuckeroth, R.O. Hirschsprung disease — integrating basic science and clinical medicine to improve outcomes. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 152–167. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29300049/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, A.L.; Guner, Y.S.; Sømme, S.; Quesenberry, A.C.; Arthur, L.G.; Sola, J.E.; Downard, C.D.; Rentea, R.M.; Valusek, P.A.; Smith, C.A.; et al. Management and outcomes for long-segment Hirschsprung disease: A systematic review from the APSA Outcomes and Evidence Based Practice Committee. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 56, 1513–1523. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33993978/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muise ED, Cowles RA. Rectal biopsy for Hirschsprung’s disease: a review of techniques, pathology, and complications. Vol. 12, World Journal of Pediatrics. Institute of Pediatrics of Zhejiang University; 2016. p. 135–41.

- Noblett, H.R. A rectal suction biopsy tube for use in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1969, 4, 406–409. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5803818/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prato, A.; Martucciello, G.; Jasonni, V. Solo-RBT: a new instrument for rectal suction biopsies in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung's disease. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2001, 36, 1364–1366. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11528606/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conces, M.R.; Beach, S.; Pierson, C.R.; Prasad, V. Submucosal Nerve Diameter in the Rectum Increases With Age: An Important Consideration for the Diagnosis of Hirschsprung Disease. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2022, 25, 263–269. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34791945/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, B.; Sengupta, M.; Das, C.; Mukhopadhyay, M.; Barman, S.; Mukhopadhyay, B. Immunohistochemistry-based comparative study in detection of Hirschsprung’s disease in infants in a Tertiary Care Center. J. Lab. Physicians 2017, 9, 076–080. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC5320884/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudorkinová, D.; Škába, R.; Lojda, Z.; Dubovská, M. Application of NADH tetrazolium reductase reaction in perioperative biopsy of dysganglionic large bowel. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1994, 4, 362–365. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7748837/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang M, Li K, Li S, Yang L, Yang D, Zhang X, et al. Calretinin, S100 and protein gene product 9.5 immunostaining of rectal suction biopsies in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’ disease. Am J Transl Res [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 Jan 5];8(7):3159. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC4969453/.

- Rakhshani, N.; Araste, M.; Imanzade, F.; Panahi, M.; Tameshkel, F.S.; Sohrabi, M.R.; Niya, M.H.K.; Zamani, F. Hirschsprung Disease Diagnosis: Calretinin Marker Role in Determining the Presence or Absence of Ganglion Cells. Iran. J. Pathol. 2016, 11, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qasim, B.J.; Musa, Z.; Ghazi, H.F.; Al Shaikhly, A.W.A.K. Diagnostic roles of calretinin in hirschsprung disease: A comparison to neuron-specific enolase. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 60–66. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC5329979/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.W.; Johnson, G. Acetylcholinesterase in Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2005, 21, 255–263. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15759143/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsois L, Boman F, Sfeir R, Besson R, Gottrand F, Boccon-Gibod L. [Synaptophysin expression abnormalities in Hirschsprung’s disease]. Ann Pathol [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2023 Jan 5];24(5):407–15. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15738866/. [CrossRef]

- Comes, G.T.; Ortolan, E.V.P.; Moreira, M.M.d.M.; Junior, W.E.d.O.; Angelini, M.C.; El Dib, R.; Lourenção, P.L.T.d.A. Rectal Biopsy Technique for the Diagnosis of Hirschsprung Disease in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 494–500. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33416267/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedmacher, F.; Puri, P. Rectal suction biopsy for the diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy and complications. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2015, 31, 821–830. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26156878/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croffie JM, Davis MM, Faught PR, Corkins MR, Gupta SK, Pfefferkorn MD, et al. At what age is a suction rectal biopsy less likely to provide adequate tissue for identification of ganglion cells? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr [Internet]. 2007 Feb [cited 2023 Apr 13];44(2):198–202. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jpgn/Fulltext/2007/02000/At_What_Age_Is_a_Suction_Rectal_Biopsy_Less_Likely.8.aspx. [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Smith, C.A.; Bradford, M.C.; Ambartsumyan, L.; Kapur, R.P. Rectal suction biopsy versus incisional rectal biopsy in the diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2022, 38, 1989–1996. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36171348/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørn, N.; Rasmussen, L.; Qvist, N.; Detlefsen, S.; Ellebæk, M.B. Full-thickness rectal biopsy in children suspicious for Hirschsprung's disease is safe and yields a low number of insufficient biopsies. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 1942–1944. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29426767/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).