Submitted:

24 July 2023

Posted:

25 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

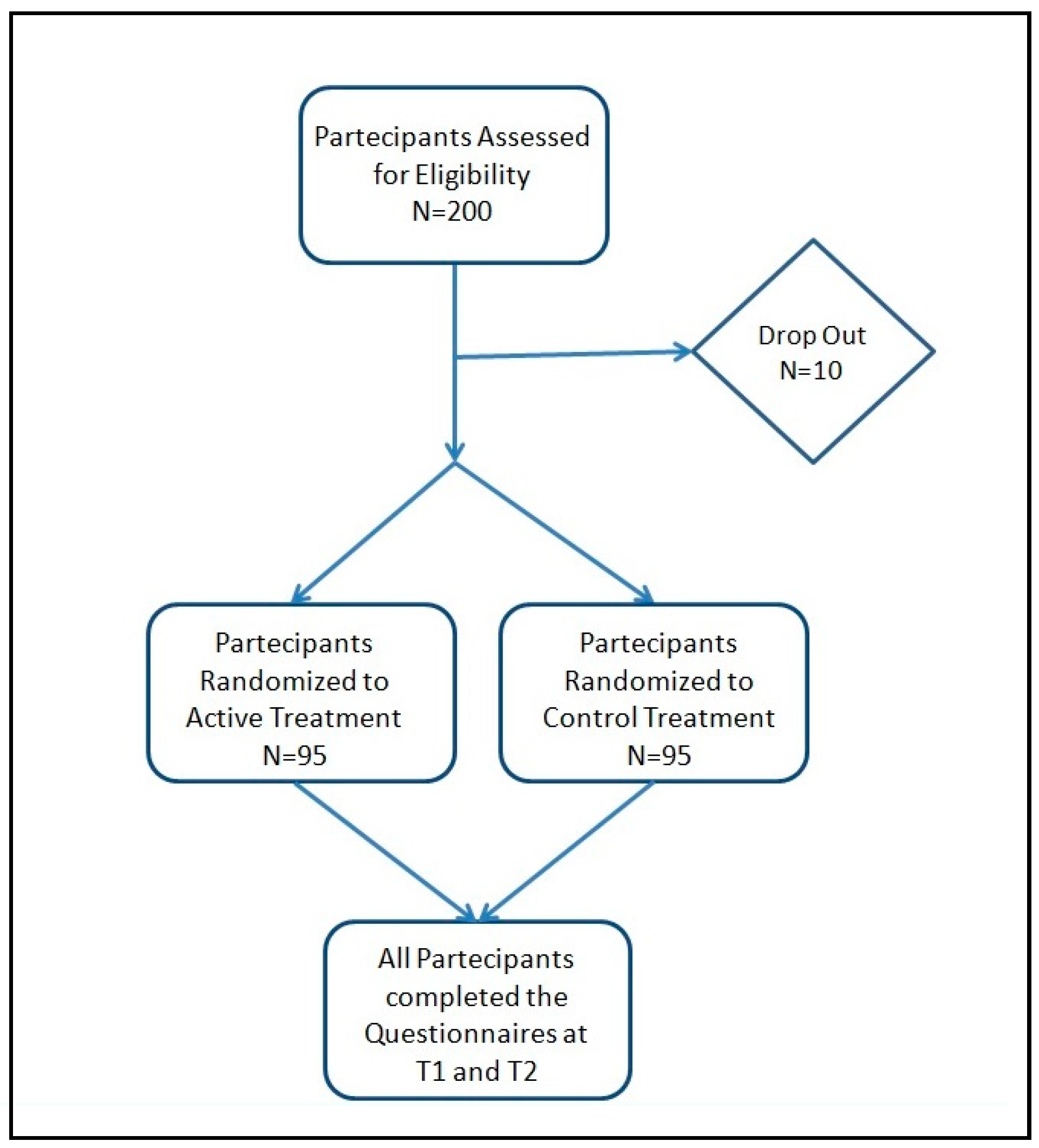

2.1. Study design, population and products

2.2. Outcome measures

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

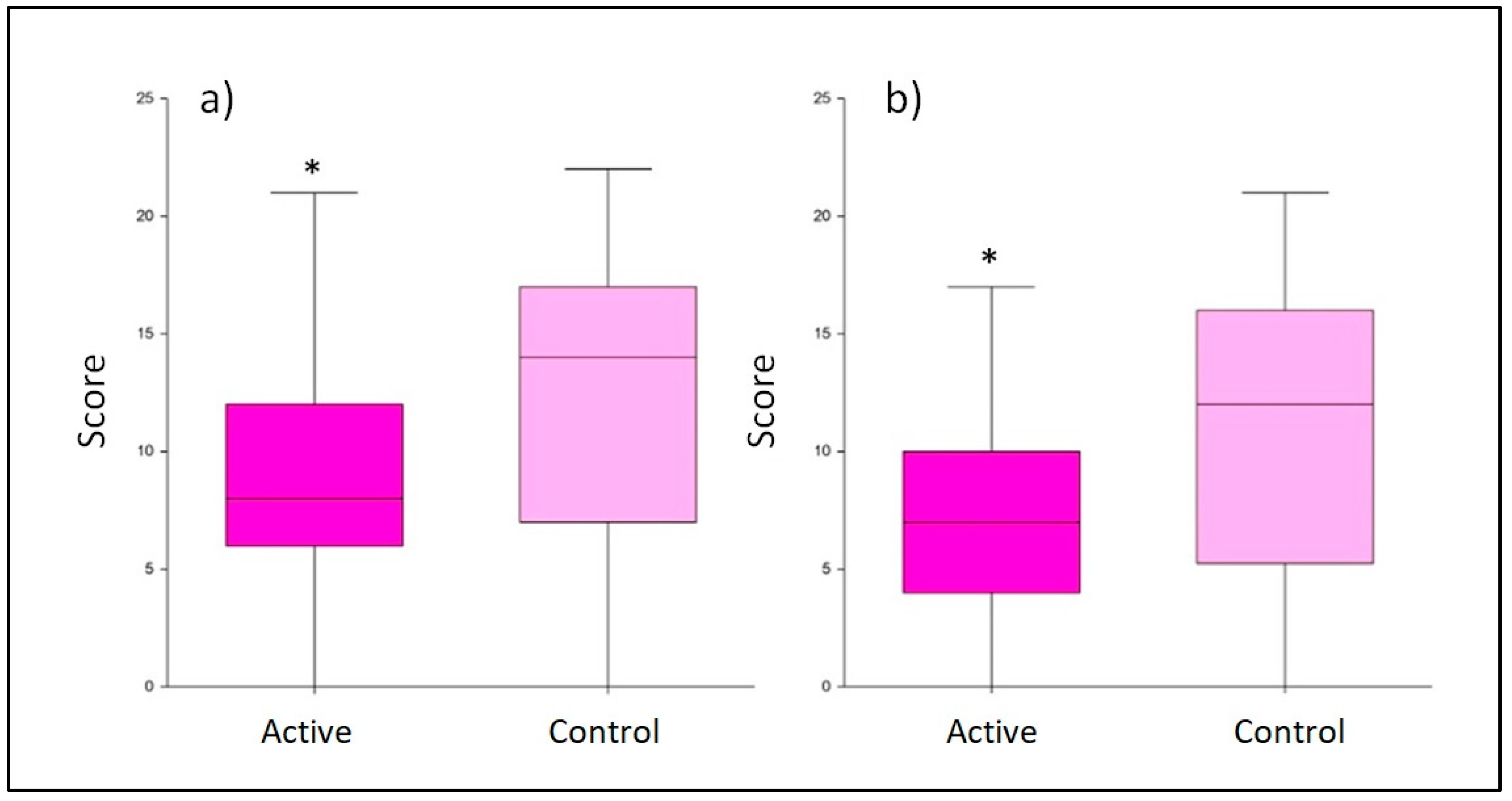

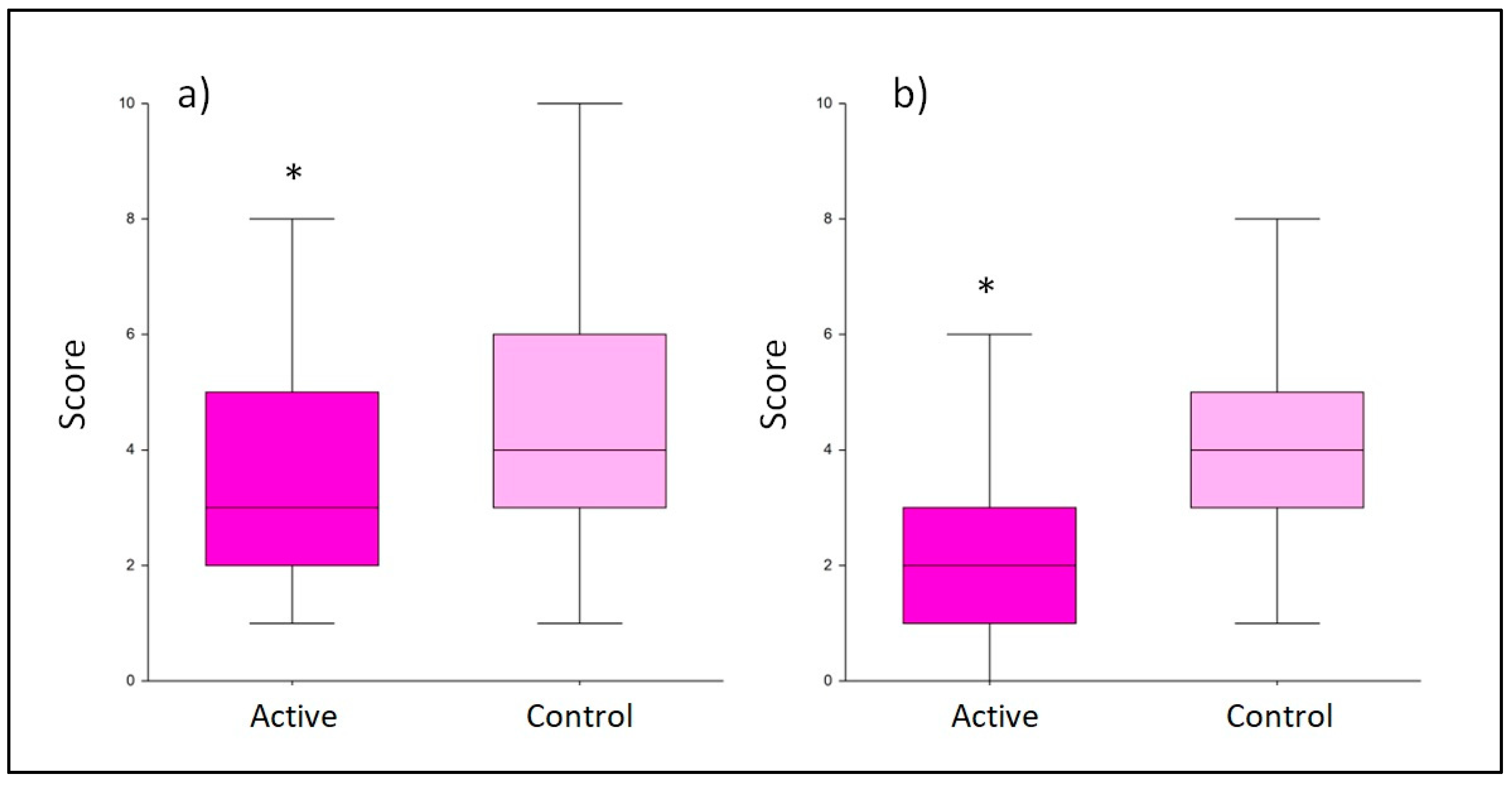

3.1. Depression symptoms evaluation

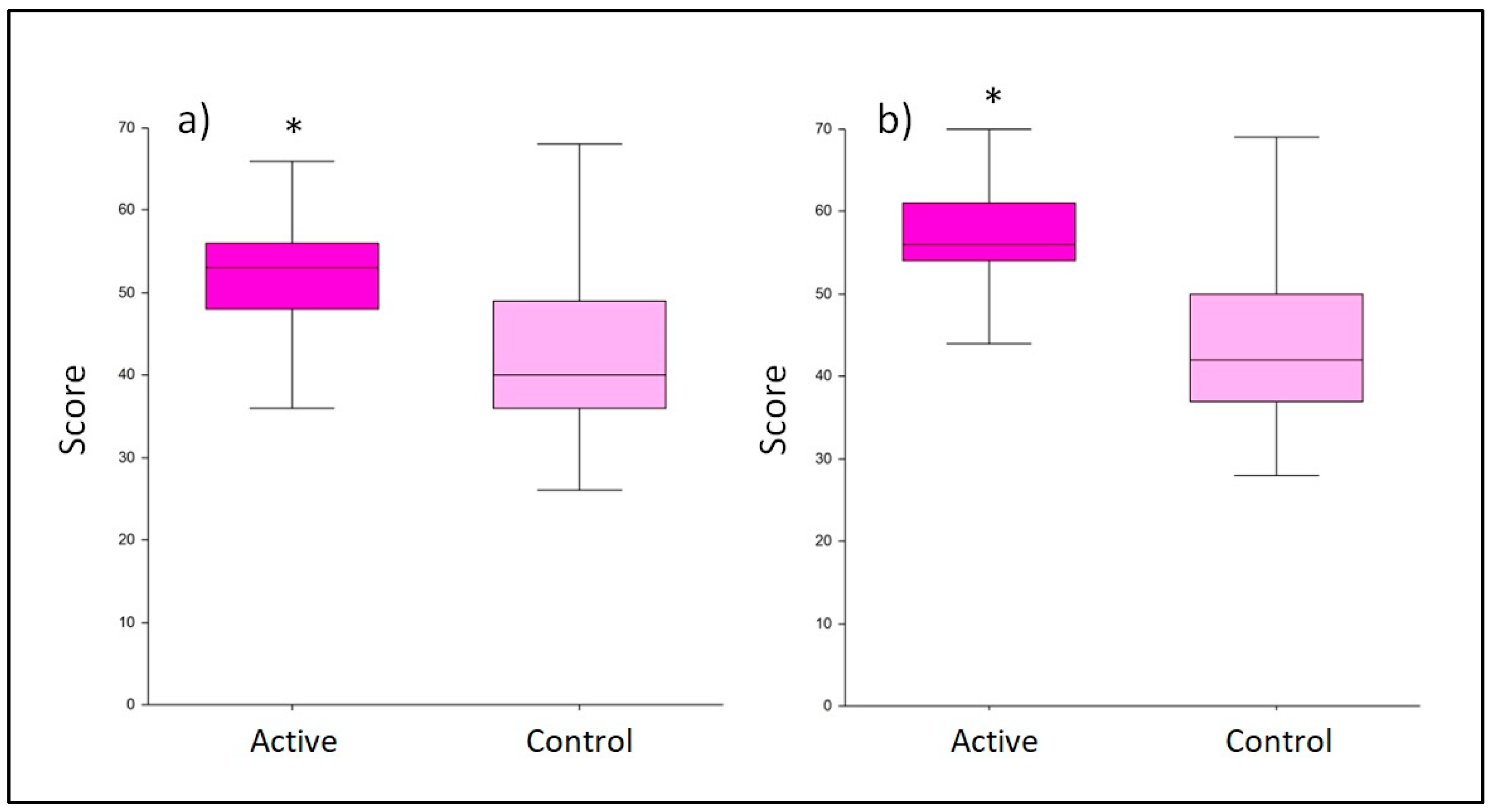

3.2. Breastfeeding quality assessment

3.4. Baby’s crying/fussing events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdollahi, F.; Rezai Abhari, F.; Zarghami, M. Post-Partum Depression Effect on Child Health and Development. Acta Med Iran. 2017, 55, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guintivano, J.; Sullivan, P.F.; Stuebe, A.M.; Penders, T.; Thorp, J.; Rubinow, D.R.; Meltzer-Brody, S. Adverse life events, psychiatric history, and biological predictors of postpartum depression in an ethnically diverse sample of postpartum women. Psychol Med. 2018, 48, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mughal, S.; Azhar, Y.; Siddiqui, W. Postpartum Depression. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Manjunath, N.G.; Venkatesh, G.; Rajanna, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Postpartum Blue is Common in Socially and Economically Insecure Mothers. Indian J Community Med. 2011, 36, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kołomańska-Bogucka, D.; Mazur-Bialy, A.I. Physical Activity and the Occurrence of Postnatal Depression-A Systematic Review. Medicina. 2019, 55, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falana, S.D.; Carrington, J.M. Postpartum Depression: Are You Listening? Nurs Clin North Am. 2019, 54, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anokye, R.; Acheampong, E.; Budu-Ainooson, A.; Obeng, E.I.; Akwasi, A.G. Prevalence of postpartum depression and interventions utilized for its management. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, C.E.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Rubinow, D.R. The role of reproductive hormones in postpartum depression. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, M.; Rotenberg, N.; Koren, D.; Klein, E. Risk factors associated with the development of postpartum mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2005, 88, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.L.; Maguire, J. Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in postpartum depression. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 52, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çapik, A.; Durmaz, H. Fear of Childbirth, Postpartum Depression, and Birth-Related Variables as Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Childbirth. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018, 15, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health (Lond). 2019, 15, 1745506519844044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, B.; Dias, C.C.; Brandão, S.; Canário, C.; Nunes-Costa, R. Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: state of the art review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013, 89, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreas, N.J.; Kampmann, B.; Mehring Le-Doare, K. Human breast milk: A review on its composition and bioactivity. Early Hum Dev. 2015, 91, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, C.M.; Felice, J.P.; O'Sullivan, E.; Rasmussen, K.M. Breastfeeding and health outcomes for the mother-infant dyad. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013, 60, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulou, A.; Field, D.; Ryan, C.A.; Stanton, C.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. The microbiology and treatment of human mastitis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2018, 207, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, R.; Martín, V.; Maldonado, A.; Jiménez, E.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, J.M. Treatment of infectious mastitis during lactation: antibiotics versus oral administration of Lactobacilli isolated from breast milk. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 50, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, S.; Arroyo, R.; Jiménez, E.; Marín, M. L.; del Campo, R.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, J. M. Staphylococcus epidermidis strains isolated from breast milk of women suffering infectious mastitis: potential virulence traits and resistance to antibiotics. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitelson, E.; Kim, S.; Baker, A.S.; Leight, K. Treatment of postpartum depression: clinical, psychological and pharmacological options. International journal of women's health. 2010, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenit, M.C.; Sanz, Y.; Codoñer-Franch, P. Influence of gut microbiota on neuropsychiatric disorders. World J Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 5486–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuco, A.; Urits, I.; Hasoon, J.; Chun, R.; Gerald, B.; Wang, J. K.; Kassem, H.; Ngo, A.L.; Abd-Elsayed, A.; Simopoulos, T.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O. Current Perspectives on Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Depression. Adv Ther. 2020, 37, 1328–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, C.A.; Diaz-Arteche, C.; Eliby, D.; Schwartz, O.S.; Simmons, J.G.; Cowan, C.S.M. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression - A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021, 83, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobile, V.; Giardina, S.; Puoci, F. The Effect of a Probiotic Complex on the Gut-Brain Axis: A Translational Study. Neuropsychobiology. 2021, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nobile V, Puoci F. Effect of a Multi-Strain Probiotic Supplementation to Manage Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Clinical. Neuropsychobiology 2023, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, P.; Ferrara, M.; Niccolai, C.; Valoriani, V.; Cox, J.L. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Italian sample. J Affect Disord. 1999, 53, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.; Cormick, G.; Amyx, M.M.; Gibbons, L.; Doty, M. , Brown, A.; Norwood, A.; Daray, F. M.; Althabe, F.; Belizán, J. M. Factors associated with postpartum depression in women from low socioeconomic level in Argentina: A hierarchical model approach. J Affect Disord. 2018, 227, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.A.; Shamsuddin, N.H.; Ridhuan, R.D.A.R.M.; Amalina, N.; Sallahuddin, N.K.D. Breastfeeding practice, support, and self-efficacy among working mothers in a rural health clinic in Selangor. J Malaysian Journal of Medicine Health Sciences. 2018, 14, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, G. Stress: Concepts, Definition and History. Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Slykerman, R. F.; Hood, F.; Wickens, K.; Thompson, J.M.D.; Barthow, C.; Murphy, R.; Kang, J.; Rowden, J.; Stone, P.; Crane, J.; Stanley, T.; Abels, P.; Purdie, G.; Maude, R.; Mitchell, E.A. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in Pregnancy on Postpartum Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: A Randomised Double-blind Placebo-controlled Trial. EBioMedicine. 2017, 24, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthow, C.; Wickens, K.; Stanley, T.; Mitchell, E.A.; Maude, R.; Abels, P.; Purdie, G.; Murphy, R.; Stone, P.; Kang, J.; Hood, F.; Rowden, J.; Barnes, P.; Fitzharris, P.; Craig, J.; Slykerman, R.F.; Crane, J. The Probiotics in Pregnancy Study (PiP Study): rationale and design of a double-blind randomised controlled trial to improve maternal health during pregnancy and prevent infant eczema and allergy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, A.; Lin, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, X. Fecal microbiota transplantation from chronic unpredictable mild stress mice donors affects anxiety-like and depression-like behavior in recipient mice via the gut microbiota- inflammation-brain axis. Stress(Amsterdam,Netherlands). 2019, 22, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, J. K.; Michaelsen, T. Y.; Bundgaard-Nielsen, C.; Nielsen, R. E.; Hjerrild, S.; Leutscher, P.; Wegener, G.; Sørensen, S. Faecal microbiota transplantation from patients with depression or healthy individuals into rats modulates mood-related behaviour. Scientific reports. 2021, 11, 21869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, A.; Pawankar, R.; Cuello-Garcia, C.; Ahn, K.; Al-Hammadi, S.; Agarwal, A.; Beyer, K.; Burks, W.; Canonica, G.W.; Ebisawa, M.; Gandhi, S.; Kamenwa, R.; Lee, B.W.; Li, H.; Prescott, S.; Riva, J.J.; Rosenwasser, L.; Sampson, H.; Spigler, M.; Terracciano, L.; … Schünemann, H.J. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University Guidelines for Allergic Disease Prevention (GLAD-P): Probiotics. The World Allergy Organization journal. 2015, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Palladino, V.; Amoruso, A.; Pindinelli, S.; Mastromarino, P.; Fanelli, M.; Di Mauro, A.; Laforgia, N. Rationale of Probiotic Supplementation during Pregnancy and Neonatal Period. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, A.A. Infant Colic. Seminars in pediatric neurology, 2016, 23, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weerth, C.; Fuentes, S.; Puylaert, P.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiota of infants with colic: development and specific signatures. Pediatrics. 2013, 131, e550–e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryl, R.; Szajewska, H. Probiotics for management of infantile colic: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Archives of medical science: AMS. 2018, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, K.; Lau, E.; Greenberg, S.; Jacobson, S.; Yazdani-Brojeni, P.; Verma, N.; Koren, G. Probiotics for infantile colic: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938. J Pediatr. 2015, 166, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, V.; Collett, S.; de Gooyer, T.; Hiscock, H.; Tang, M.; Wake, M. Probiotics to prevent or treat excessive infant crying: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics. 2013, 167, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Good general health condition | Subjects who do not meet the inclusion criteria |

| Women in the first trimester post-partum | Subjects considered as not adequate to participate to the study by the investigator |

| Aged between 18 and 50-year-old (extremes included) | Subjects with known or suspected sensitization to one or more test formulation ingredients |

| Willingness to breastfeed* | Adult protected by law (under control or hospitalized in public or private institutions for reasons other than research, or incarcerated) |

| Willingness to use probiotics and multivitamin food supplements that will be consigned at the last visit before delivery | Subjects not able to communicate or cooperate with the investigator for problems related to language, mental retardation or impaired brain function |

| Willingness to fill-up questionnaire | Subjects suffering from other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder or substance use disorder |

| Willingness to use only the products to be tested during all the study period | Subjects with serious physical illnesses or mental disorders due to a general medical condition which are judged by the investigator to render unsafe |

| Willingness not to use similar products that could interfere with the product to be tested | Subjects with significant risk of infanticide according to the investigator assessment |

| Willingness not to vary the normal daily routine (i.e. lifestyle, physical activity, etc.) | Subjects taking herbal remedies or psychotropic drugs that are intended for depression are taken within the last 2 weeks prior to baseline or during the study |

| Subjects aware of the study procedures and having signed an informed consent form | Subjects receiving counselling or psychological therapies at baseline or during the study |

| Subjects who do not meet the inclusion criteria |

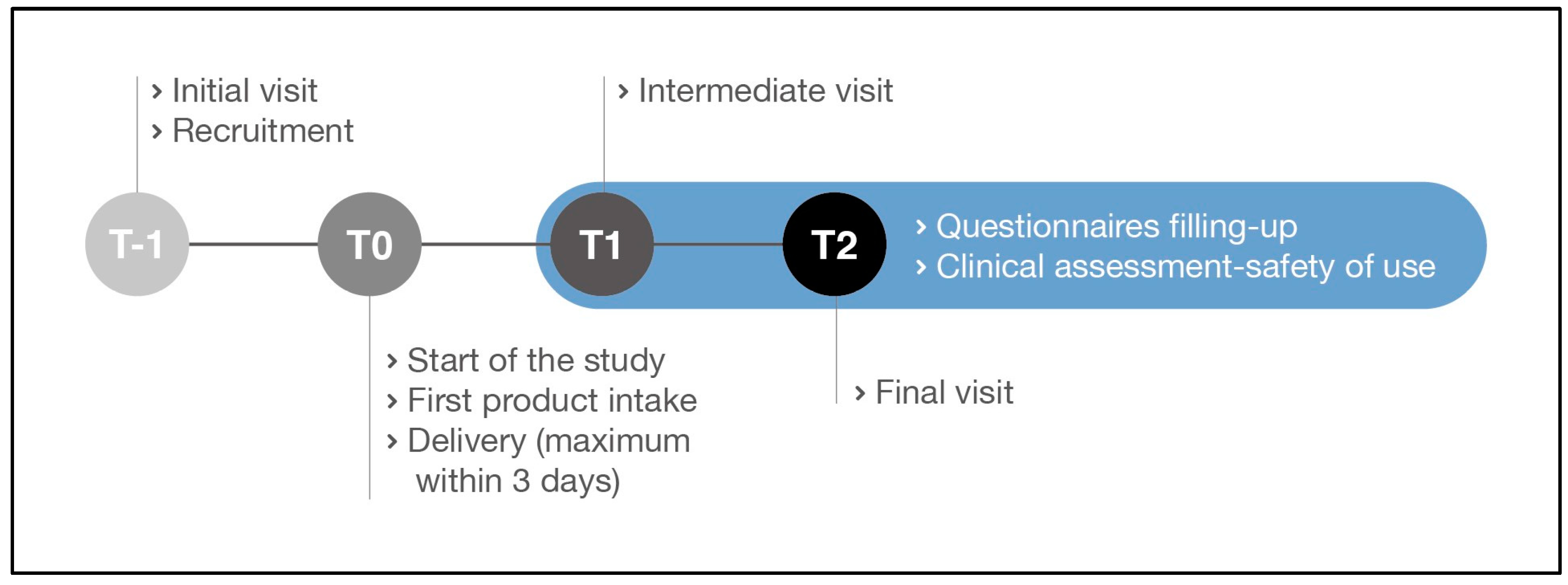

| Study phases | Initial visit Recruitment (T-1) |

Start of the study Product intake (T0) |

Intermediate visit (T1) |

Final visit (T2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signed Informed consent | X | - | - | - |

| Subject eligibility | X | - | X | X |

| Clinical assessment-safety of use | - | - | X | X |

| Questionnaires filling-up supported by the gynecologist | - | - | X | X |

| Products distribution | X | - | - | - |

| Unused product collection | - | - | - | X |

| Treatment | Answer at T1 | Answer at T2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

Active product (probiotics plus multivitamins) |

77 | 18 | 74 | 21 |

|

Control (multivitamins only) |

40 | 55 | 41 | 54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).