1. Introduction

Sustainable development is a model of development that improves human well-being in the long term without destroying the environment (United Nations [UN], 1972). This concept means that human well-being cannot be achieved at the cost of environmental damage, which raises the question of how sustainable development can be interpreted from the perspective of small private enterprises (Parrish, 2010). Sustainable development oriented businesses should endure business activities while contributing to sustainable development (Atkinson, 2000). Entrepreneurship as an engine of economic development should support rapid growth while also focusing on sustainable development goals. Sustainably oriented entrepreneurship helps to avoid environmental degradation, promote social transformation, and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Conversely, the SDG agenda also has implications for entrepreneurship, as it takes into account the importance of organizations operating in interdependent, complex environments that require balancing economic, social, human, and ecological goals[

1].

Entrepreneurship is considered as an economic engine, or new businesses that create jobs, by providing goods and services to customers and contributing to economic growth (Rahdari et al., 2016; Vazquez-Brewster and Sarkis, 2012). Entrepreneurs can contribute to social transformation and support products and services produced in a sustainable manner. Thus, a sustainable orientation of entrepreneurship contributes to achieving the SDGs and avoiding environmental degradation. On the other hand, the sustainable development agenda can also influence entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial orientation is defined as the act of "innovating in the product market, taking certain risks, and competing proactively with competitors" (Miller, 1983). Entrepreneurial orientation includes initiative, innovation, and risk-taking, and can positively impact business performance (Razaei & Ortt, 2018). Entrepreneurial orientation emphasizes aspects of process, practice, and decision-making activities (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996), promotes innovation, and helps determine the market potential of a firm (Kiyabo & Isaga, 2020).

Sustainability, as an effort to balance economic, social, human, and ecological goals, takes into account the fact that organizations operate in complex, interdependent environments. As revealed by Schaltegger et al. (2018), the SDGs can be achieved by providing better working conditions, fair income, and compensation for employment prospects. Eradicating poverty by creating more employment options and good jobs for everyone is essential to achieve the eighth goal of the SDGs (Weidinger, 2014).

Sustainable development is inseparable from rural areas, which are the producers of food and resources and provide ecosystems of natural services. At the same time, in the context of modern industrialization/urbanization, rural areas also face a range of environmental, social and economic problems that affect the process of sustainable development to some extent. For rural areas, sustainable development is also important because it provides a model of development that meets the needs of the present without undermining the development opportunities of future generations. In this model, rural areas can achieve balanced ecological, economic and social development. Sustainable development can guide sustainable planning and practice in rural areas in the areas of land use, agricultural production, waste management, and resource recycling. By promoting sustainable development paths represented by eco-agriculture, green industry, and eco-tourism, resources in rural areas can be used rationally, while improving farmers' income generation and promoting local economic development and poverty eradication efforts. In addition, sustainable development helps improve the quality of life of farmers and enhances their opportunities to participate in social, cultural and educational activities.

However, today, when the gap between urban and rural development and income still exists, some of the outstanding rural talents will move to the cities, and there is still a shortage of rural talents compared to urban talents, which brings certain difficulties to the development of rural areas. Strengthening the construction of rural talents is an important part of the rural revitalization strategy, and rural revitalization cannot be achieved without the efforts of contemporary young talents. As far as the current situation of rural development is concerned, due to the relatively backward development of the countryside in terms of human resources, resources, technology and capital, the comprehensive factors of insufficient rural development hinder the introduction and cultivation of rural talents, and the development of all fields in the countryside is constrained by the talent resources. This is mainly due to the rapid development of cities, which are more attractive to talent resources compared to the countryside, leading to the active approach of talents to the cities and the increasing lack of rural talents. At the same time, due to the relatively low agricultural efficiency, relatively backward rural environment and people's traditional ideology, a large number of rural laborers go to the city, while urban talents are also reluctant to enter the countryside. The way of talent allocation under the market economy law leads to the problem of difficulty in introducing and stabilizing talents in the countryside. Some data show that at present, the proportion of young people aged 15-39, who are permanent residents in the countryside are less than 30%, even as of April 2022, although China's various types of people returning to the countryside to start their own businesses exceeded 11 million, but according to the actual research found that most of them only stayed briefly and quickly returned to the city. It can be seen that the lack of rural talents, especially young talents, has become an urgent problem to be solved in the process of rural revitalization.

To attract talent to the countryside, stay in the countryside. In order to do so, there must be a reliable platform carrier to support them, i.e. to build a platform for youth entrepreneurship and provide them with the opportunity to "show off their skills". A good and stable platform for young people to return to their hometowns can cultivate rural talents and guide young entrepreneurs; build entrepreneurial opportunities to promote agricultural modernization; and promote rural revitalization to achieve common prosperity. In short, it is important to build a platform for youth entrepreneurship.

Therefore, this study establishes a performance model of youth returning to their hometown entrepreneurship platform, analyzes the characteristics of each youth entrepreneurship platform construction through field visits and research on some youth entrepreneurship platforms, and proposes where the advantages of rural entrepreneurship platform construction lie. And on this basis, suggestions are made to universities, relevant departments, etc., in an attempt to promote the construction of youth entrepreneurship platforms in their hometowns to the greatest extent.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. The effect of the support policies for returning entrepreneurs on the self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs

Self-efficacy is based on an individual's self-perception of their skills and abilities, a concept that reflects a person's internal beliefs about whether they possess competencies that are considered important for task performance and their ability to effectively translate these skills into chosen outcomes [

2]. The concept of self-efficacy is widely used in the career-related literature to explain career choices, career preferences, and ultimately career behaviors [

3]. The same self-efficacy can exist in an entrepreneurial career. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is a belief that an individual can effectively accomplish entrepreneurial activities and succeed. Entrepreneurship is a very complex process in which individuals seek opportunities, integrate resources, build a business and build it into a successful entity, and there is a lot of uncertainty, so self-efficacy is especially important to the success of entrepreneurs [

4].

Social contextual plasticity is one of the important influencing factors of self-efficacy. The external environment, including supportive policies and family support, can have an exemplary or encouraging effect on entrepreneurs' career perceptions and willingness to make choices, and the support of the external environment can also have an impact on entrepreneurs' self-efficacy. On the one hand, policies are crucial for entrepreneurial activities, and governments can facilitate the establishment of an institutional environment that encourages productive entrepreneurship through policies [

5]. On the other hand, entrepreneurial support policies can promote the impact of entrepreneurial enthusiasm on psychological capital accumulation [

6]. In conclusion, entrepreneurial policies can create a favorable climate for entrepreneurial behavior and reduce uncertainty in the early stages of entrepreneurship, which, to some extent, increases entrepreneurial propensity and makes entrepreneurs willing to consistently repeat entrepreneurship in the future after analyzing the feasibility of entrepreneurship, thereby increasing self-efficacy. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1: Support policies for hometown entrepreneurship can significantly and positively affect the entrepreneurial performance of firms

2.2. The Impact of Returning Entrepreneurship Support Policies on the Service and Design of Rural Crowdsourcing Spaces

As a new type of cross-border network effect platform, crowdsourcing space is highly participatory and innovative, and its essence is to provide innovation and entrepreneurship services, resources and knowledge for enterprises or users through platform sharing, which is a resource collaboration and co-creation process of all participating subjects on the platform. The survival and development of rural crowdsourcing spaces depends on whether they can bring dual value-added innovation and entrepreneurship service network resources to the platform organization and the returning entrepreneurs. Relying only on the power of rural crowdsourcing spaces themselves, they have limited ability and resource channels to provide relatively professional high-level services such as mentorship, science and technology policy consultation, entrepreneurship training, and business management improvement, on top of providing basic services such as physical space, equipment and equipment, and business and taxation agency. Based on the limited service resources and service behavior limitations of rural crowdsource spaces, the government's appropriate intervention through the introduction of policies becomes an important means to ensure the service capacity of rural crowdsource spaces can be improved. At the same time, the high risks and uncertainties faced by rural entrepreneurship require the government to act as a "manager", "supervisor" and "guide". At the same time, the government needs to play the roles of "manager", "supervisor" and "guide", and make up for the shortcomings of various services in rural crowdsourcing spaces through appropriate interventions, so as to indirectly boost the competitiveness of the platform in terms of its service capacity and its ability to incubate creators' innovation and entrepreneurship. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: Support policies for hometown entrepreneurship can significantly and positively influence the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces

2.3. The impact of rural crowdsourcing space services and design on the self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs

The services of rural crowdspaces mainly include are technical support, financial support, and social support [

7]. Technical support mainly refers to the crowdsourcing space providing office space, tools, materials and relevant training to help enterprises reach their goals [

8]. Financial support refers to crowdsourcing spaces providing enterprises with relevant resources at relatively low prices, and crowdsourcing spaces can absorb funds from the government, related organizations and universities for enterprises to further reduce innovation costs [

9]. Social support means that crowdsourcing spaces create a platform for enterprises to learn and communicate, and organize some group discussions to gain innovation opportunities through communication and cooperation with other enterprises, in which creators can learn new skills from like-minded friends and collaborate. It is the rich and diverse resources that bring greater competitive advantage and better service capabilities, bringing more opportunities for entrepreneurs while enhancing their self-efficacy.

The behavior people exhibit is largely influenced by the spatial environment they live in, so the innovative activities of creators in crowdspaces are also influenced by the crowdspace design itself. In the definition of crowdspace, it is emphasized that crowdspaces are often based on the gathering of physical locations to carry out innovative activities [

10], while the advantages of crowdspace design are not only limited to the design of physical spaces, but also the "social" aspects of crowdspace design [

11]. Therefore, the crowdsourcing space should not only have a relatively independent office space, but also provide a communication area for the creators. Different entrepreneurs gather together through crowdsourcing spaces, using the open design of the space to share information and resources, promote the spread of ideas, and collide to create sparks [

12]. Good space design provides opportunities for inadvertent communication and collision of innovative ideas, which can promote knowledge interaction among creators, facilitate knowledge overflow and birth of new ideas, and thus enhance the self-efficacy of entrepreneurs [

13].

This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3: Rural crowdsourcing space services and design can significantly and positively influence the self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs

2.4. The effects of entrepreneurial platform services and design, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial support policies on corporate entrepreneurial performance

The physical environment is an external factor that inevitably plays a role in individual behavior. The design of the physical environment affects people's emotions and changes their performance to some extent (Loomans et al., 2018). According to environmental psychology, there is an interactive relationship between humans and their physical environment. Platform structure empowerment emphasizes that individuals can gain more knowledge, support, and opportunities by engaging in an environment that can fully empower them [

14]. That is, the physical layout of the workspace can have a significant impact on employee productivity and thus on organizational performance (Yerkes, 2003).

The higher the self-efficacy of an entrepreneur, the more able he or she will be to lead the company to higher revenue and employment growth rates [

15]. Entrepreneurs with higher self-efficacy will have a greater ability to increase their chances of success, including accurately assessing knowledge gaps in themselves and in their networks, creating comprehensive skills and competencies to solve problems, and learning to tolerate disagreements. Also, self-efficacy is important for the acquisition and maintenance of competitive advantage in new ventures, and high self-efficacy of business founders in innovation facilitates risk-taking and financial control, thus increasing business success [

16].

Governments create greater economic prosperity by developing policies that transform an economic environment with little entrepreneurial activity into one that provides greater incentives for individuals in the public or private sector to develop innovative entrepreneurial activity in a more consistent and systematic manner [

17]. For example, the Reagan economic policy reforms (Reaganomics) in the United States and Thatcherism (Thatcher ism) in the United Kingdom (economic reforms introduced by Prime Minister Thatcher) greatly stimulated the transition of the private sector to entrepreneurship.

This leads to the following hypothesis:

H4: Entrepreneurial support policies, entrepreneurial platform services and design, and entrepreneurial self-efficacy all significantly and positively influence business entrepreneurial performance

2.5. The mediating role of entrepreneurship platform services and design on entrepreneurship support policies and firm entrepreneurial performance

Government policies play an extremely important guiding role in the process of resource and service driven operational performance improvement. Chen et al. showed that the implementation of government policies plays an extremely important role in guiding and facilitating the daily operation and performance evaluation of crowdspaces, and that more reasonable financial subsidies and tax incentives can significantly improve the operational efficiency of crowdspaces [

18]. The study by Pieterse and Rese et al. also confirmed the facilitating relationship between entrepreneurial platform services and design on business entrepreneurial performance. The results indicate that other elements such as the design of crowdsourcing spaces, arranged activities, and provided resources can be targeted to meet firms' needs, provide a creative environment, and can facilitate the generation of innovative activities, ultimately contributing to the improvement of tenants' innovation performance [

19,

20]. Thus government policy supported entrepreneurial platform services and design have the potential to contribute to the growth of entrepreneurial performance of firms.

This leads to the following hypothesis:

H5: Entrepreneurial platform services and design mediate the significant impact of entrepreneurship support policies on firm entrepreneurial performance

2.6. The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial support policies and business start-up performance

According to the social cognitive perspective, self-efficacy is influenced by three factors: the individual's analysis of the task, the attribution of past success or failure, and the individual's evaluation of the environment in which he or she finds himself or herself [

21]. For example, a study by Wu et al. demonstrated that external environmental factors such as policies directly affect the development of self-efficacy, and that entrepreneurial self-efficacy is higher when entrepreneurs perceive a better entrepreneurial environment [

22]. Also, entrepreneurs who have greater confidence in the tasks to be accomplished and the roles to be performed in the entrepreneurial process gain more advantages. This is because entrepreneurs with high self-efficacy set higher entrepreneurial goals for themselves and their ventures in the entrepreneurial process, and high goal consistency makes them work harder to achieve their goals and show more perseverance and persistent behavior in the face of difficulties and setbacks, thus better contributing to entrepreneurial performance [

23]. Thus the self-efficacy developed by entrepreneurs due to government policy support is likely to contribute to the growth of entrepreneurial performance of firms.

This leads to the following hypothesis:

H6: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the significant impact of entrepreneurial support policies on business start-up performance

3. Research methods

3.1. Population and sample

This study was conducted by means of a questionnaire using a five-point Likert scale, and the questions were mainly adopted from the scales used in published academic papers at home and abroad. Before distributing the questionnaire, the research team contacted the director of the crowdsourcing space to explain the main content of the study and to obtain permission and support to enter the space.

3.2. Latent variables and indicators

In the concept manipulation, we give the definition of each concept. As shown in

Table 1, the analysis uses the following metrics in the latent variables.

The measurement of variables is carried out using a theoretical construct framework in which the variable or the structure called definition should have a definition which consists of genus approximation and variance specific (Ihalaw, 2008). The generic approximation as a general term determines the metric (nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio), while the difference specific determines the empirical indicator. The expected empirical metrics adequately reflect the constructs that achieve the isomorphic conditions.

The indicators of the support policies for returning home to entrepreneurship were obtained from the performance evaluation index system of the support policies for returning home to entrepreneurship by Fang Ming et al [

24], the indicators of the self-efficacy of returning home to entrepreneurship youth were obtained from the entrepreneurial self-efficacy measurement questionnaire by Huihui Li and Yongchun Huang et al [

25,

26], and the indicators of the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and the indicators of enterprise innovation performance were obtained from the crowdsourcing space design, service and enterprise innovation performance constructed by Ying Han et al The empirical model [

27].

Table 1.

Latent variables and indicators.

Table 1.

Latent variables and indicators.

| Latent variables |

Definition |

Indications |

| Support policies for hometown entrepreneurship |

Policies and laws enacted and implemented by the government that have a critical impact on the motivation and home-based entrepreneurial activities of returning entrepreneurs [28] |

ZFZC1:Support policy promotion efforts |

| ZFZC2:Support policy benefit degree |

| ZFZC3:Financial support efforts |

| ZFZC4:Degree of implementation of entrepreneurship training |

| ZFZC5:Satisfaction with economic conditions |

| ZFZC6:Support policy satisfaction |

| ZFZC7:Satisfaction with production and operation conditions |

| ZFZC8:Business Development Satisfaction |

| ZFZC9:Satisfaction with training effectiveness |

| Self-efficacy of returning young entrepreneurs |

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is a belief that an individual can effectively accomplish entrepreneurial activities and succeed |

ZWXN1:Confident to start a company and keep working |

| ZWXN2: Confidence in controlling the creation process of a new company |

| ZWXN3:Know the practical details necessary when starting a business |

| ZWXN4:Know how to develop a startup project |

| ZWXN5:Believe that you can succeed if you want to start a company |

| Rural Crowdsourcing Service and Design |

The innovation and entrepreneurship service network resources unique to the rural crowdsourcing platform that can bring double value-added to the platform organization and returning entrepreneurs |

FWYSJ1:The design of rural crowdsourcing spaces can stimulate creative thinking |

| FWYSJ2:The design of rural crowdsourcing space is interesting |

| FWYSJ3:The design of rural crowdsourcing spaces can improve the quality of ideas |

| FWYSJ4:The services of rural crowdsourcing spaces are conducive to building internal networks |

| FWYSJ5:Rural crowdsourcing services facilitate access to external resources |

| FWYSJ6:Rural crowdsourcing services provide access to capital |

| FWYSJ7:The services of Village Crowdspace include some training and activities |

| Corporate Entrepreneurial Performance |

The extent to which a task is completed or a goal is reached in the course of entrepreneurship |

CXJX1: You can produce new products (services) in rural crowdsourcing spaces in priority to your competitors |

| CXJX2:New products (services) can be produced in rural crowdsourcing spaces that are as good as those of competitors |

| CXJX3:Improved products can be developed in rural crowdsourcing spaces |

| CXJX4:New markets can be opened in rural crowdsourcing spaces |

| CXJX5:New profit points can be generated in the rural crowdsourcing space |

| CXJX6:Market share can be increased in the rural crowdsourcing space |

| CXJX7:In the village crowdsourcing can increase production and reduce labor costs |

3.3. Data analysis

PLS-SEM is used to test the construction of a home-based entrepreneurship platform for the sustainability of youth home-based entrepreneurship. PLS-SEM consists of a set of multivariate techniques that are validating rather than exploratory in testing whether the model fits the data. We used Stata software to propose six testable hypotheses.

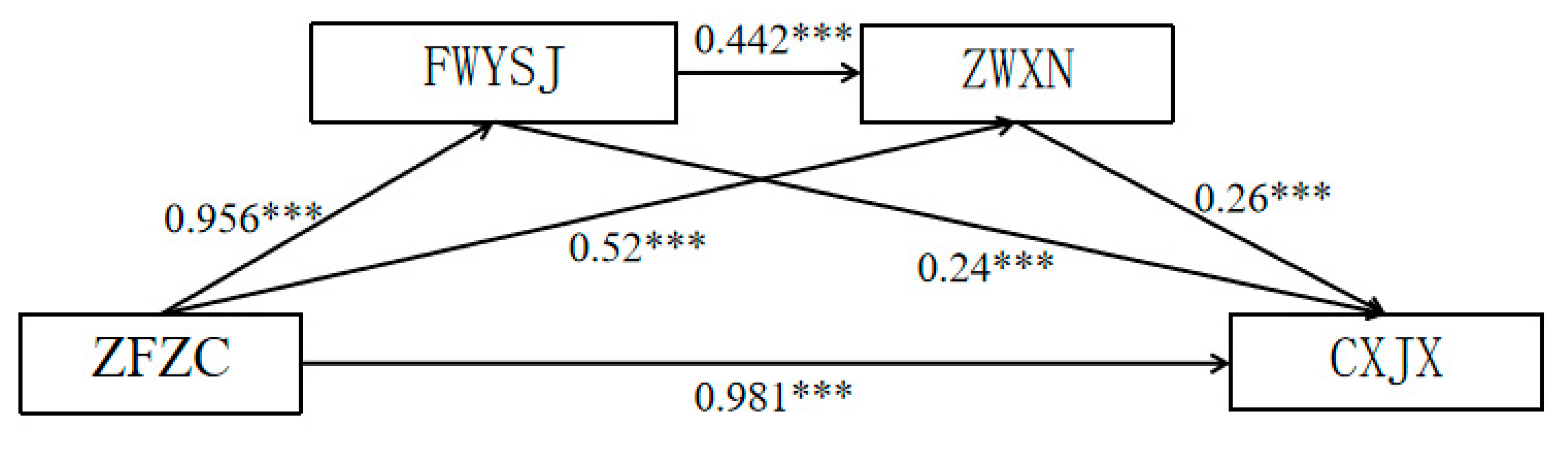

Figure 1 shows the interrelationships between the supportive policies for hometown entrepreneurship, self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurial youth, rural crowdsourcing services and design, and firm innovation performance.

We evaluated reflexive measurement model criteria such as internal consistency (Cronbach's α and composite reliability) and convergent validity (mean extracted variance and indicator reliability). In this regard, indicator reliability should be higher than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2014). cronbach's alpha should be greater than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2014). The mean variance of the extracts should be greater than 0.5. the composite reliability should be greater than 0.7 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). In this study, the goodness of fit (GoF) index was also used as model appropriateness (Henseler and Sarstedt, 2013).

4. Analysis and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the survey respondents. Most respondents are young entrepreneurs aged 21-30, and interestingly, the ratio of men to women is balanced, indicating that more and more women are choosing to start their own businesses. Most of the entrepreneurs' education is above college and university, reflecting the generally higher education level of entrepreneurs and the improved quality of returning entrepreneurs.

4.2. Scoring of indicators

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the empirical indicators. All variables fall into the very high category, with the highest self-efficacy score (3.71) for returning youth entrepreneurs. This is because the survey respondents are returning entrepreneurs in rural crowdsourcing spaces, who themselves have relatively high willingness and confidence in returning to their hometown.

Among all the empirical indicators of the support policies for hometown entrepreneurship, people generally recognize the strength of government support policies in terms of publicity (3.73), but they are less satisfied in the aspects of government financial support, satisfaction with production and operation conditions, satisfaction with enterprise development and satisfaction with government training effects, which indicates that entrepreneurs need more financial and training help from the government.

Among all the empirical indicators of rural crowdsourcing space services and design, it is believed that the design of rural crowdsourcing spaces still needs to be improved in terms of interestingness (3.64). The improvement of funness is conducive to expanding the innovative way of thinking of entrepreneurs, thus helping them to generate more high-quality business ideas. Thus a low score for funness is consistent with the score that the design of rural crowdspaces can improve the quality of ideas (3.65).

Among all the empirical indicators of enterprise innovation performance, entrepreneurs scored low (3.63) on "market share can be increased in rural crowdsourcing spaces", indicating their lack of confidence in the market competitiveness provided by rural crowdsourcing spaces. Market share refers to the proportion of the sales volume (or sales) of a product (or category) among similar products (or categories) in the market, which reflects the position of an enterprise in the market. The higher the market share, the stronger the competitiveness. The size of the market share directly affects the production scale and cost of the enterprise, so the indicator "We can increase production and reduce labor cost in the village crowdsourcing space" also scored relatively low.

4.3. Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of each variable

The means, standard deviations and correlation coefficients of each variable are shown in

Table 1. From the table, it can be seen that there is a significant positive correlation between the support policy for hometown entrepreneurship, the service and design of rural crowdsourcing space, the self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurs and the entrepreneurial performance of enterprises. There is a significant positive correlation between the support policy for hometown entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial performance of enterprises (r=0.957, p<0.001); a significant positive correlation between the support policy for hometown entrepreneurship and the self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurs (r=0.943, p<0.001); a significant positive correlation between the support policy for hometown entrepreneurship and the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces (r=0.956, p< 0.001); there was a significant positive correlation between self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial performance of enterprises (r=0.941,p<0.001); there was a significant positive correlation between service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and entrepreneurial performance of enterprises (r=0.946,p<0.001).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for each variable (n=468).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for each variable (n=468).

| Variables |

M±SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

| 1 Return to home to support entrepreneurial policies |

3.69±1.22 |

|

|

|

| 2 Service and design of rural crowdsourcing space |

3.70±1.14 |

0.956** |

|

|

| 3 Self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs |

3.71±1.14 |

0.943** |

0.939** |

|

| 4 Business start-up performance |

3.68±1.15 |

0.957** |

0.946** |

0.941** |

-

3. Result

Note: * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001, same below.

4.4. Multiple stepwise regression analysis among the variables

In this study, multiple stepwise regression analysis was conducted with corporate entrepreneurial performance as the dependent variable and the support policy for returning entrepreneurs, the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs as predictor variables. The results are shown in

Table 2, and the corresponding regression equations are:

Business start-up performance = 0.492×supporting policies for returning entrepreneurs + 0.243×services and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces + 0.263×self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs - 0.014

In this case, the model explains 93.4% of the firm's entrepreneurial performance.

Table 5.

Multiple stepwise regression analysis among variables.

Table 5.

Multiple stepwise regression analysis among variables.

| Variables |

Non-standardized coefficient |

Standardization factor Beta |

t |

P |

R2 |

∆R2 |

| β |

Standard Error |

| Support policies for hometown entrepreneurship |

0.492 |

0.046 |

0.481 |

10.615 |

0.000 |

0.934 |

0.934 |

| Service and design of rural crowdsourcing space |

0.243 |

0.044 |

0.24 |

5.456 |

| Self-efficacy of returning entrepreneurs |

0.263 |

0.039 |

0.262 |

6.762 |

| Constant term |

-0.014 |

0.048 |

|

-0.29 |

0.772 |

4.5. A test of the moderating role that rural crowdsourcing venues' design and customer service have on returning entrepreneurs' confidence in their ability to launch successful businesses

Multiplef mediation models were developed according to the mediation effects test procedure

1, and the fit of the models and the significance of the coefficients of each path were tested in the bias-corrected nonparametric percentile Bootstrap method using 5000 replicate samples in the SPSS macro PROCESS of Hayes

2.

In order to explore the indirect influence of the support policy for hometown entrepreneurship on the entrepreneurial performance of enterprises through the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and the self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurs, and to clarify the internal mechanism of the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and the self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurs between them, this study uses the support policy for hometown entrepreneurship and its indicators as the independent variables, the entrepreneurial performance of enterprises and its indicators as the dependent variables, and the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and the self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurs as the mediating variables. The structural equation model M is constructed with the support policy and its indicators as the independent variables, the enterprise entrepreneurship performance and its indicators as the dependent variables, and the service and design of rural crowdsourcing space and the self-efficacy of hometown entrepreneurs as the mediating variables. The fit index of model M is: 0.724, and the relevant model fit assessment indexes are within the standard reference value, indicating that the fit index of model M is excellent, which provides a good basis for further testing.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM framework output.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM framework output.

Table 6 displays the findings of a more thorough analysis of the mediating effects.

Table 6 shows that none of the three mediating routes' confidence intervals contain 0 and that they all reach a significant level. The two mediating variables of service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and self-efficacy of return entrepreneurs and both of them played a chain mediating role in it were found to mediate 49.16% of the effect of the return entrepreneurship support policy on the entrepreneurial performance of enterprises.

Table 6.

Intermediary effect values and effect sizes.

Table 6.

Intermediary effect values and effect sizes.

| Intermediary Pathway |

Intermediary effect value |

Bootstrap SE |

Boot CI Lower |

Boot CI Upper |

Relative effect size(%) |

| ZFZC→FWYSJ→CXJX |

0.272 |

0.054 |

0.454 |

0.663 |

23.92 |

| ZFZC→ZWXN→CXJX |

0.160 |

0.031 |

0.101 |

0.223 |

14.07 |

| ZFZC→FWYSJ→ZWXN→CXJX |

0.127 |

0.234 |

0.084 |

0.176 |

11.17 |

| Total indirect effect |

0.559 |

0.054 |

0.454 |

0.663 |

49.16 |

3.1. Subs

5. Discussion

Past research has shown that many entrepreneurs pay particular attention to political market dynamics as well as business markets [

29,

30,

31,

32] because of the broad influence of government or politics on business activities in emerging economies [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. In particular, the rapid changes in government policies in the political arena provide a constant stream of opportunities for entrepreneurs [

38,

39,

40]. Entrepreneurs who actively follow these changes in government policies may identify more opportunities and take advantage of them by engaging in entrepreneurial activities, ultimately creating value for their businesses [

41].The results of this study build on this foundation and validate the positive impact of entrepreneurship policies on entrepreneurial performance.

It has been shown that some macro-level public policy factors can influence the impact of entrepreneurship platforms on entrepreneurship. Therefore, many scholars propose to promote the construction and development of entrepreneurship platforms through policies. For example, Shen Xiaochun summarizes the active role of the government in the development of crowdsourcing spaces: first, to take crowdsourcing spaces as an important grip of regional dual innovation; second, to introduce preferential policies to support the development of crowdsourcing spaces to stimulate the vitality of "dual innovation"; third, to strengthen the classification and guidance of crowdsourcing spaces to strengthen demonstration and leadership [

42]. Liu classifies China's crowdspaces into government-led and market-led according to the differences in the behaviors of investment subjects, and makes policy suggestions: first, the government needs to dynamically adjust its governance strategies to support the development of crowdspaces according to the evolution of the industrial environment; second, the government needs to strengthen the supervision of crowdspaces to prevent the market crowding effect; third, attention should be paid to the "government hand" and the "market" when formulating policies to support crowdspaces. Third, when formulating policies to support crowdsourcing spaces, attention should be paid to the difference in regulation between the "government hand" and the "market hand" to prevent institutional dependence and subsidy dependence [

43].

The work environment and organization in which employees work is the organizational environment, such as organizational culture, organizational innovation climate, organizational rewards, leadership style, promotion system, and team atmosphere, etc. Damanpour et al. found that the establishment of innovation climate within an organization and the stimulation of employees' innovation can be influenced by the organizational culture established by the top and senior management in the organization [

44], and crowdsourcing spaces are no exception. For example, Van Holma argues that makerspaces influence innovative entrepreneurial activities by stimulating creators' creativity, building social networks, and reducing startup costs [

45]. Hypothesis III validates these ideas.

The fourth hypothesis predicts the effects of policies, platforms, and entrepreneurs themselves on entrepreneurial performance, and this hypothesis is supported empirically. Our findings support the view of Shaosheng Huang et al. They concluded that platform digital empowerment significantly enhanced entrepreneurial performance, entrepreneurial psychological capital played a partial role in the digital pathway of platform digital empowerment to enhance entrepreneurial performance, and entrepreneurial policy orientation positively moderated the impact of platform digital empowerment on entrepreneurial performance [

46].

Finally, this study documents an indirect (mediating) effect of entrepreneurial platform services and design on the relationship between entrepreneurial support policies and business entrepreneurial performance, which is consistent with Yingyan Wang's [

47]study. In addition, the study showed the indirect (mediating) effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on the relationship between entrepreneurship support policies and business entrepreneurial performance. This result was able to corroborate with the findings of Xianyue Liu [

48]and Song Lin [

49], among others. In conclusion, the key roles of entrepreneurial platform services and design and entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurial support policies and business entrepreneurial performance are empirically supported.

6. Conclusion

This paper extends the research framework on the impact of home-based entrepreneurship policies on entrepreneurial performance with a sample of 468 young people returning to their hometown in rural crowdsourcing spaces, and uses structural equation modeling under this framework to explore the relationships among home-based entrepreneurship policies, rural crowdsourcing space services and design, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial performance.

1. Return-to-home entrepreneurship support policies, as a macro environment, positively influence the construction of rural entrepreneurship platforms and the self-efficacy of youth returning to their hometowns, and thus directly and indirectly positively influence business entrepreneurial performance. The results of the study emphasize the importance of hometown entrepreneurship policies in increasing the willingness of youth to return to their hometowns and promoting the construction of rural entrepreneurship platforms, and it can be seen that the hometown entrepreneurship policies in Zhejiang Province are worthy of recognition and have gained the approval of many hometown entrepreneurial youth.

2. The direct and mediating roles of service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces are evident, which can directly affect entrepreneurial performance on the one hand and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on the other. This study provides empirical evidence for the direct and mediating relationships between government policies and entrepreneurial performance by improving the services and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces and fostering the self-efficacy of returning youth.

3. Self-efficacy is an important factor in promoting entrepreneurial performance. The return home entrepreneurship policies, rural crowdspace services and design all directly or indirectly affect entrepreneurial performance through entrepreneurs' self-efficacy, i.e., the role of external environment on entrepreneurial performance is generated through self-efficacy, while self-efficacy directly affects entrepreneurial performance. Therefore, to improve the entrepreneurial performance, retain the youth who return to their hometowns and realize the sustainability of youth returning to their hometowns, it is an effective way to improve the self-efficacy of the youth who return to their hometowns by introducing relevant supporting policies, promoting the construction of rural crowdsourcing spaces and improving the self-efficacy of the youth who return to their hometowns.

Optimizing the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces can help improve entrepreneurs' self-efficacy to enhance entrepreneurial performance. The entrepreneurial environment acts on entrepreneurial performance through self-efficacy; therefore, to be effective, policies to improve the service and design of rural crowdsourcing spaces need to seek paths to enhance entrepreneurs' self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a key factor in entrepreneurial performance. In terms of management model and management capabilities, improving entrepreneurs' overall operational capabilities, enhancing knowledge and experience through entrepreneurial learning, and expanding management skills through training and education programs are conducive to entrepreneurs' continued success and thus enhanced self-efficacy.

Author Contributions

J.L. conceptualized and supervised the study; A.L. collected and analyzed the data, and prepared and finalized the manuscript; X.M. analyzed the data and prepared and finalized the manuscript; M.Z. supported the literature review and data collection; L.Z. supported the literature review and the data collection. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted with the “Evaluation system and monitoring research of private education and training institutions” (BGA180053) provided by the “General subject of pedagogy in the 13th Five-Year Plan of the National Social Science Fund in 2018”, “Online and offline hybrid virtual simulation teaching mode and its practice” (202101031035) provided by the “Ministry of Education Industry–University Cooperation Project.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable“ for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and all reviewers for their invaluable comments and advice. We also thank the research participants for their participation in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Apostu S A, Gigauri I. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship in emerging countries: Are sustainable development and entrepreneurship reciprocally reinforcing? Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 2023,27(3): 2.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change . Psychological review, 1977, 84(2): 191-192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [CrossRef]

- Betz N E, Hackett G. The relationship of career-related self-efficacy expectations to perceived career options in college women and men. Journal of counseling psychology, 1981, 28(5): 399-400. [CrossRef]

- De Noble A F, Jung D, Ehrlich S B. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action. Frontiers of entrepreneurship research, 1999, 1999(1): 73-87.

- Minniti M. The role of government policy on entrepreneurial activity: productive, unproductive, or destructive? Entrepreneurship theory and Practice, 2008, 32(5): 779-790. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00255.x. [CrossRef]

- Hu W, Xu Y, Zhao F, et al. Entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial success-the role of psychological capital and entrepreneurial policy support. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Han S Y, Yoo J, Zo H, et al. Understanding makerspace continuance: a self-determination perspective. Telematics and Informatics, 2017, 34(4): 184-195. [CrossRef]

- Seo J, Lysiankova L, Ock Y S, et al. Priorities of coworking space operation based on comparison of the hosts and users' perspectives. Sustainability, 2017, 9(8): 1494. [CrossRef]

- 9. Fontichiaro K. Sustaining a makerspace . 2016, 12(3): 19.

- Han S Y, Yoo J, Zo H, et al. Understanding makerspace continuance: a self-determination perspective. Telematics and Informatics, 2017, 34(4): 184-195. [CrossRef]

- Bechtel C, Ness D L. If you build it, will they come? Designing truly patient-centered health care. Health affairs, 2010, 29(5): 914-920. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse A N, Van Knippenberg D, van Ginkel W P. Diversity in goal orientation, team reflexivity, and team performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2011, 114(2): 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Sailer, K. Creativity as social and spatial process. Facilities, 2011, 29(1/2): 6-18. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, X.; Song, X.; Li, Y. Evolution of Enterprise Organization Structure Based on the Hypothesis of Empower to Enable: Based on the Case Study of Handu Group's Practice. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 9, 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- Baum J R, Locke E A. The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of applied psychology, 2004, 89(4): 587. [CrossRef]

- Sweida G L, Reichard R J. Gender stereotyping effects on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and high-growth entrepreneurial intention. Journal of small business and enterprise development, 2013, 20(2): 296-313. [CrossRef]

- Leyden, D.P. Public-sector entrepreneurship and the creation of a sustainable innovative economy. Small Bus Econ 46, 553-564 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chang, Xiang, Liyao, Yu, Rongjian. The entrepreneurial ecosystem of crowdsourcing space:characteristics, structure, mechanism and strategy--a case study of Hangzhou Dream Town. Business Economics and Management, 2015(11):35-43. [CrossRef]

- Rese A, Kopplin C S, Nielebock C. Factors influencing members' knowledge sharing and creative performance in coworking spaces. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2020, 24(9): 2327-2354. [CrossRef]

- Pieterse A N, Van Knippenberg D, van Ginkel W P. Diversity in goal orientation, team reflexivity, and team performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2011, 114(2): 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Gist M E, Mitchell T R. Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management review, 1992, 17(2): 183-211. [CrossRef]

- Wu JZ, Li YB. A study on the influence of perceived entrepreneurial environment on middle managers' intrapreneurial behavior. Journal of Management,2015,12(01):111-117.

- Zhong Weidong, Huang Zhaoxin. An empirical study on the relationship between relationship strength, self-efficacy and entrepreneurial performance of entrepreneurs. China Science and Technology Forum, 2012(01): 131-137. https://doi.org10.13580/ j. cnki. fstc.2012.01.008.

- Fang M,Zhang T,Liu M-L. Performance evaluation and policy orientation of support policies for migrant workers returning to their hometowns for entrepreneurship--based on the survey data of national enterprises returning to their hometowns for entrepreneurship. Journal of Anhui University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 2021, 45(06): 122-132. https://doi.org10. 13796/ j. cnki.1001-5019.2021.06.015.

- Li Huihui,Huang Shasha,Sun Junhua,Feng Xiao. Social support, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial well-being. Foreign Economics and Management,2022,44(08):42-56. https://doi.org10.16538/j.cnki.fem.20220506.402.

- Huang Y., C. ,Zhang W. J.,Xu J. H. The influence of service environment on entrepreneurial orientation of nascent entrepreneurs. Scientific Research Management, 2021, 42(02):149-160. https://doi.org10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2021.02.015.

- Han Ying,Chen Guohong. Crowdsourcing space design, services and firm innovation performance. Scientific Research Management,2022,43(05):67-75https://doi.org10.19571/j.cnki.1000-2995.2022.05.008.

- RAQUEL FONSECA, PALOMA LOPEZ-GARCIA, CHRISTOPHER A. PISSARIDES. Entrepreneurship, start-up costs and employment. European Economic Review,2001,45(4/6):692-705. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. Double entrepreneurship in China's economic reform: an analytical framework. Journal of Political & Military Sociology, 2002: 134-147.

- Yang, K. Institutional holes and entrepreneurship in China. The Sociological Review, 2004, 52(3): 371-389. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. Entrepreneurship in China [M]. Routledge, 2016: 37.

- Bruton G D, Ahlstrom D, Obloj K. Entrepreneurship in emerging economies: where are we today and where should the research go in the future. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 2008, 32(1): 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Dai W, Arndt F, Liao M. Hear it straight from the horse's mouth: recognizing policy-induced opportunities[M]// Entrepreneurship in China. Routledge , 2021: 56-76.

- 34. Liu Y, Dai W, Liao M, et al. Social status and corporate social responsibility: Evidence from Chinese privately owned firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 2021, 169: 651-672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04547-9. [CrossRef]

- 35. Peng M W. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of management review, 2003, 28(2): 275-296. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.9416341. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Vahlne J E. Dynamic capabilities of emerging market multinational enterprises and the Uppsala model . Asian Business & Management, 2020: 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-020-00111-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Tan J, Wong P K. When does investment in political ties improve firm performance? The contingent effect of innovation activities. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 2015, 32: 363-387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-014-9402-z. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W. Regional deregulation and entrepreneurial growth in China's transition economy. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 2011, 23(9-10): 853-876. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.577816. [CrossRef]

- Dai W, Liu Y, Liao M, et al. How does entrepreneurs' socialist imprinting shape their opportunity selection in transition economies? Evidence from China's privately owned enterprises. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2018, 14: 823-856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0485-0. [CrossRef]

- Dai W, Si S. Government policies and firms' entrepreneurial orientation: strategic choice and institutional perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 2018, 93: 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.026. [CrossRef]

- Qian G, Liu B, Wang Q. Government subsidies, state ownership, regulatory infrastructure, and the import of strategic resources: Evidence from China . Multinational Business Review, 2018, 26(4): 319-336.

- Zhang Hongshi,Shen Xiaochun. Play the role of government in promoting the development of crowdsourcing space. Guangxi Economy,2016(01):51-52. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202307.1649.v1. [CrossRef]

- Liu J. Ecological mechanisms of government and market participation in the creation of crowdsourcing spaces--Evidence based on 52 municipal administrative regions across China. East China Economic Management, 2018, 32(07): 55-64. https://doi.org/10.19629/j.cnki.34-1014/f.171016021. [CrossRef]

- Damanpour F, Schneider M. Phases of the adoption of innovation in organizations: effects of environment, organization and top managers 1. British journal of Management, 2006, 17(3): 215-236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.00498.x. [CrossRef]

- 45. Van Holm E J. Makerspaces and contributions to entrepreneurship. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2015, 195: 24-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.167. [CrossRef]

- Huang Shaosheng,Yan Chun. A study on the impact of platform digital empowerment on entrepreneurial performance - the role of entrepreneurial psychological capital and entrepreneurial policy orientation. Modern Management Science, 2022, No.336(05):90-97. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202307.1649.v1. [CrossRef]

- Yingyan Wang, Rui Zeng, "The Model of Makerspace Development Element and Performance Analysis Based on NVivo Classification", Scientific Programming, vol. 2021, Article ID 7123961, 11 pages, 2021. https: // doi-org-s.ssl. hznu. edu. cn: 8118/10.1155/2021/7123961.

- Liu X , Lin C , Zhao G , et al. Research on the Effects of Entrepreneurial Education and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy on College Students' Entrepreneurial Intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 2019, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00869. [CrossRef]

- Lin S , Si S . Factors affecting peasant entrepreneurs' intention in the Chinese context. International Entrepreneurship & Management Journal, 2014, 10(4):803-825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0325-4. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Wen Zhonglin,Ye Baojuan. Mediation effect analysis:Methods and model development[J]. Advances in Psychological Science,2014,22(05):731-745. |

| 2 |

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach.New York:The Guilford Press. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).