1. Introduction

Aging can come with a range of diseases and debilitation, such as cognitive and physical decline, depressive symptoms, and emotional changes, which can directly affect the balance between nutritional needs and intake [

1]. Elderly individuals' dietary behavior may change due to health or social reasons, decreased taste and smell, or reduced physical strength needed to purchase and prepare food. İmpairment of health increasingly, increased use of health services, and mortality are the result of malnutrition and unconscious weight loss.

The main purpose of nutrition planning in the elderly is to provide adequate amounts of energy, protein, micronutrients, and fluid requirements to maintain or improve the nutritional status [

2]. Experimental and community studies support increased energy and protein intake in the elderly due to the maintenance of muscle mass, body function, and overall health [

3].

Due to decreasing collagen synthesis with aging, collagen supplementation is an inevitable need. The most important source of meeting this need is the consumption of bone and bone broth. But again, it is important to take into account the blood cholesterol levels that arises with aging. This is because foods that are sources of collagen also have high cholesterol levels. Collagen hydrolysates are also produced industrially as an alternative to animal foods. Collagen hydrolysates in liquid and powder form as food supplements are recommended by experts for both bone and tissue health and skin health. In terms of elderly nutrition, it is possible to add collagen to foods that the elderly consume frequently [4, 5]

2. Materials and Methods

The strained honey, labneh cheese, cream, corn starch, vanillin, collagen, baking powder, milk, sunflower oil, tahini, dates, oats, roasted hazelnut kernels, roasted pistachio kernels, dried black grapes, walnut kernels, cashews, dried apricots, granulated sugar, flour, eggs, pumpkin and spinach were purchased from the local market and purified water was used in the study.

2.1. Preparation of Samples

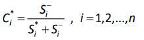

The ingredients, recipes, and production stages of the bar samples developed in the study were sensory determined through preliminary trials. In this study, 5 different bar samples were designed (

Table 1). Sample C is the "control sample" without collagen, date puree, pumpkin puree, and tahini, samples P1 and P2 contain tahini, pumpkin puree and different ratios (x and 2x ratios) of collagen, samples D1 and D2 contain tahini, date puree and different ratios (x and 2x ratios) of collagen. All other components and construction stages of the bar samples are the same.

The preparation of bar samples consists of 4 stages: preparation of the top layer, preparation of the intermediate layer, preparation of the base layer, and the stages of joining the layers.

Preparation of the top layer of bar samples

The nuts (hazelnuts, salted peanuts, black grapes, walnuts, cashews, apricots), oats, and honey specified in

Table 1 were mixed with a whisk in 20 saucepans, poured into a rectangular adjustable cake mold with greaseproof paper on the bottom and baked in a convection oven (Empero, Turkey) at 180°C for 10 minutes and the granola layer was prepared.

Preparation of the intermediate layer (puree layer) of the bar samples

Peeled and chopped pumpkin was poured with water and granulated sugar and kept at 15°C for 24 hours, then cooked in its own juice for about 20 minutes and pureed with the help of a blender (Sinbo, Turkey) to be used in the interlayers of P1 and P2 bar samples. When the consistency of puree was formed, the cream was added and mixed to add flavor.

The pitted dates to be used in the interlayers of D1 and D2 samples were cooked by boiling in water and pureed with the help of a blender. When the consistency of puree was formed, the cream was added and mixed to add flavor.

To make an intermediate layer with the purees, whisk together the labneh cheese and granulated sugar, then add the cream, vanilla, flour, corn starch, and eggs. Purees were added to the mixture according to the sample type.

Preparation of the base layer of bar samples

For the preparation of the base layer of the samples, spinach puree was first obtained. Washed and de-stalked 10 pieces of spinach were blanched and pureed with the help of a blender. By using a blender, whisk the eggs and granulated sugar for 5 minutes, then add milk, sunflower oil, spinach puree, flour, vanilla, and baking powder and whisk again. This mortar was poured into a mold with greaseproof paper on the bottom and half-baked in a preheated convection oven at 170°C for 10 minutes (

Figure 1).

Combining layers

The intermediate layer mortar was poured on the base layer after the semi-cooking process and semi-cooked in a steam oven at 160°C for 15 minutes. Puree according to the sample type was spread on the cooled bar with the help of a pallet and the top layer (granola) was placed on it. Thus, our bar samples were prepared for sensory analysis.

2.2. Sensory Analysis

The sensory analysis of the bar samples was carried out in two repetitions by a group of 20 panelists (15 male-15female) who were trained sensorial analysis. Panelists were asked to rate flavor, odor, appearance, structure and overall taste of bar samples on a scale of 1 (worst) to 5 (best) [

6]. The mean score of each sensory attribute was calculated by averaging the scores obtained from two repetitions [

7]. The evaluation was carried out in a sensory analysis laboratory equipped with individual cabinets with temperature control (20-25°C) and white light. Participants were instructed to drink water between samples to minimize residual effects.

2.3. Ethics Committee Approval

The ethical approval of the study was obtained with the decision of Sivas Cumhuriyet University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Social and Human Sciences Board dated 29.04.2022 and numbered E-60263016-050.06.04-159557.

2.4. Application of TOPSIS Technique to Sensory Analysis

TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity) Method

This method was developed by Hwang and Yoon in 1980 and is a Multi-criteria Decision Making method that has found application in many fields. The evaluation of alternatives (decision options) is based on two basic points: the positive ideal solution and the negative ideal solution. The TOPSIS method aims to identify the decision option that is the shortest distance from the positive ideal solution and the farthest distance from the negative ideal solution. A positive ideal solution minimizes the cost measure and maximizes the benefit measure. A negative ideal solution is, on the other hand, one that maximizes the cost measure and minimizes the benefit measure. The TOPSIS method reveals distances to positive and negative ideal solutions and also reveals ideal and non-ideal solutions.

For the method to be applicable, there must be at least two decision options. With an analysis process that does not involve complex algorithms and mathematical models, the TOPSIS method finds application in many fields due to its ease of use and easy understanding and interpretation of the results. There are application areas such as personnel selection, supplier evaluation, and selection, location selection, mapping of mineral potentials in mineral deposits research, robot selection, and industry [

8].

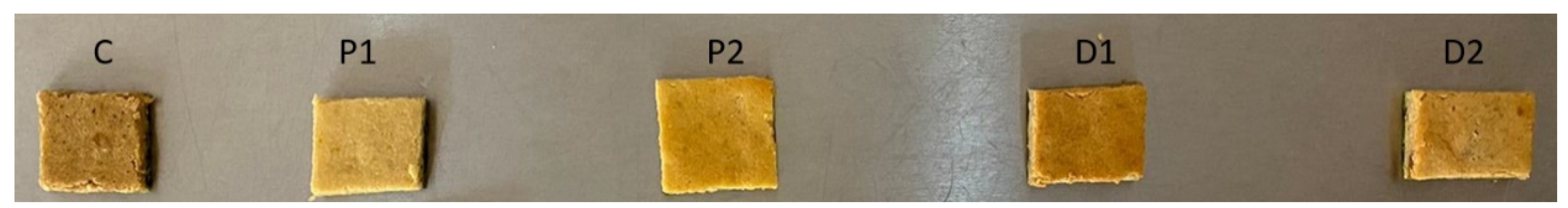

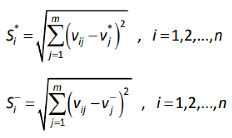

In this study, TOPSIS method was employed for evaluating sensory properties of snack bars with different ingredients determining the distance of alternatives from the positive and negative ideal solutions, and also for ranking the treatments. Hierarchy was created by determining the importance of the criteria of flavor, odor, appearance and structure as 50%, 15%, 20% and 15% respectively (

Figure 2).

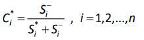

This method is summarized as the following:

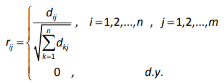

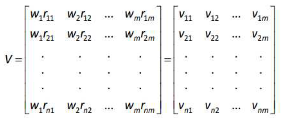

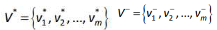

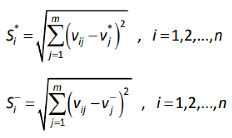

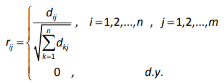

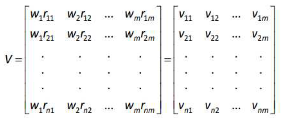

I. The construction of the decision-making matrix with m (samples) and n (flavor, odor, appearance and structure)

II. The normalization of decision-making matrix

III. To calculate the weights for the criterion and also to develop the normalized weight matrix

Vij = Wij × rij. The weight of each criterion was determined using Shannon entropy method [

9].

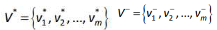

IV. Determining the positive and negative solutions

V. Determining the distance of the normalized weighted matrix from ideal positive and negative points

VI. Calculating the distance from the ideal point

2.2.5. Nutritional Analysis

Nutrient analysis of the macro and micronutrients of the bar samples was performed with the Nutrient Database Programme (BeBiS, Ebispro for Windows, Germany; Turkish Version/BeBiS 8.2)

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from the analysis of the bar samples were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and comparison was performed using Tukey's Multiple Comparison and ANOVA tests. With different formulations, bar samples were produced twice and each analysis was repeated three times.

3. Results

3.1. Sensory analysis

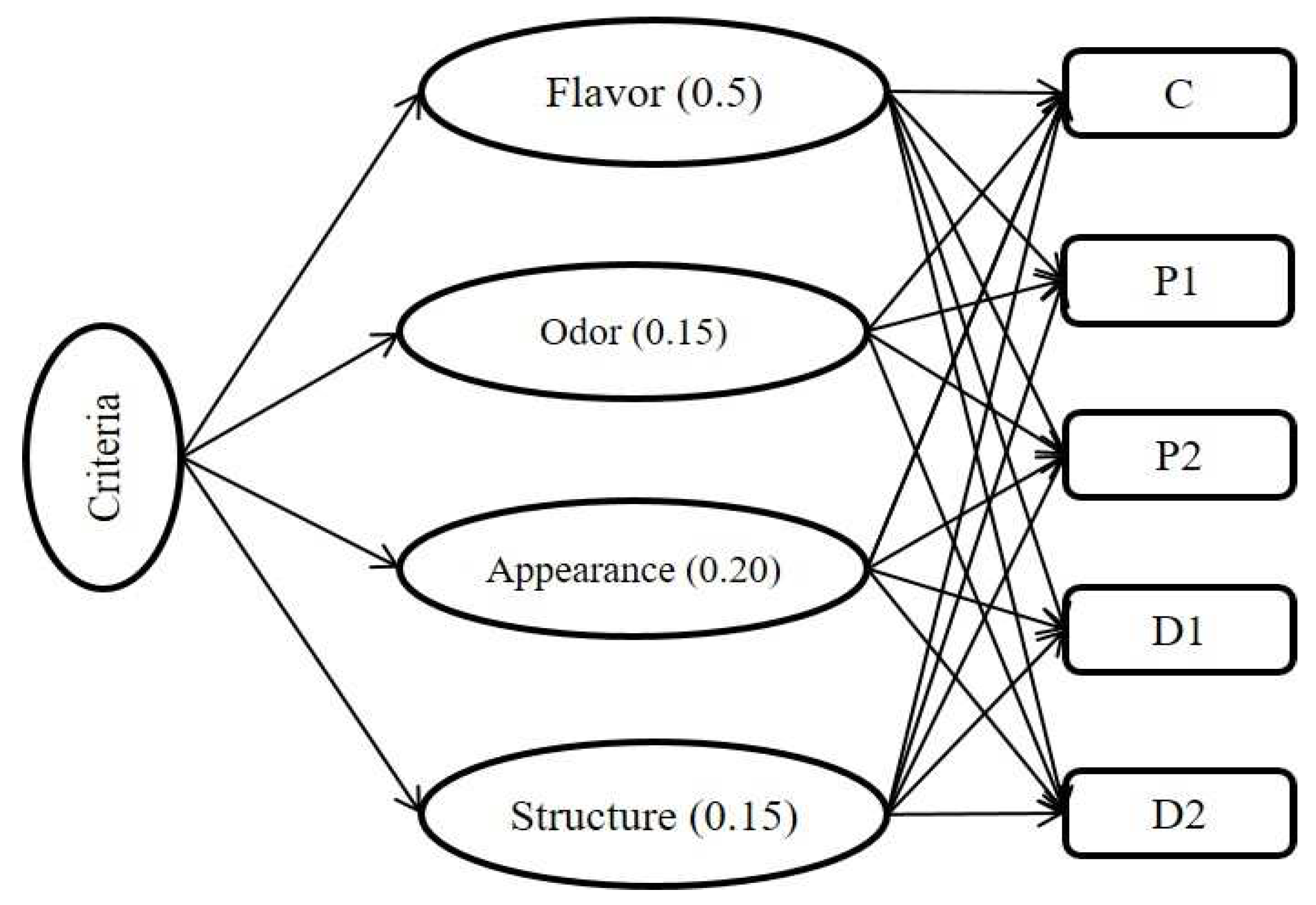

Sensory values of snack bars with different ingredients are shown in

Figure 3. In terms of appearance, the snack bar sample with low levels of pumpkin puree (P1) received the highest appearance score and the snack bar sample with high levels of pumpkin puree (P2) received the lowest appearance score (Fig. 3). It was observed that there was a statistical difference between the appearance values of the samples, but there was no difference between the odor values. When the structure values of the snacks to which pumpkin and date purees were added to provide softness suitable for consumption by elderly individuals were compared, it was determined that P1, P2, and D2 samples received the highest appreciation and the difference between the structure values of the samples was statistically significant (p<0.05). The flavor is an important criterion in terms of sensory properties and is the most important sensory parameter in industrial food production. Regarding the snack bars containing different ratios of pumpkin and date purees, the highest flavor score was found in the samples containing high levels of pumpkin puree (P2) and date puree (D2), and there was no statistical difference between the other samples. Considering the general taste values of the samples determined sensually, the highest scores were obtained for bars with high levels of date puree (D2) and low levels of pumpkin puree (P1). There was a statistical difference between the general taste values of the samples (p<0.05).

When there is a presence of multiple criteria among multiple samples, the TOPSIS technique was applied to samples of snack bars with different contents, and the decision matrix and normalized decision matrix for samples is given in

Table 2. and the ranking is given in

Table 3. In the study where the taste ranking of the samples was made, different weighted coefficients were created for 4 sensory criteria. Flavor, odor, appearance and structure criteria were weighted according to the coefficients 0.50, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.15, respectively. The most popular sample was the snack bar (D2) with high levels of date puree (Fig. 3). The sorting of the other samples was determined as a snack bar with a high level of pumpkin puree (P2), a snack bar with a low level of date puree (P1), a snack bar with a low level of pumpkin puree (P1) and a control sample with no puree (C), respectively.

3.2. Nutrients

Table 4 shows the macro and micronutrients in 1 serving of snack bars enriched with collagen and shaped in a form that elderly individuals can consume more easily with different purees.

The nutrients in 1 serving of snack bars with different ingredients are given in

Table 4. The snack bars with the highest energy content compared to the others were snack bars with low (D1) and high levels of date puree (D2). The snack bar with high levels of pumpkin puree (P2) and the snack bar with high levels of date puree (D2) had the highest protein content. Considering the amino acids glycine and proline, which play an important role in the structure of collagen, it is shown that the snack bar containing high levels of date puree (D2) has the highest content compared to the control sample (C), which contains no puree.

4. Discussion

4.1. Sensory properties

Dysphagia is recognized as a health problem in the elderly population because swallowing physiology changes with advancing age. Changes and difficulties in swallowing are also seen in healthy elderly individuals and defined as presbyphagia [

10]. In a study by Namasivayam-MacDonald and colleagues, it was reported that 59% of individuals over the age of 65 who stayed in a nursing home for a long time had suspected swallowing disorders [

11]. Therefore, to adapt to these changing functions in elderly individuals, the choice of foods that are easier to chew comes to the fore. When the structure values of the snack bars with different contents developed within the scope of the study were compared, the P1, P2, D1 and D2 samples, in which pumpkin and date purees were added to provide softness suitable for the consumption of elderly individuals, received the highest appreciation (Fig. 3). These bars, which received the highest appreciation in terms of structure, are thought to be a highly consumable alternative snack in the diet of elderly individuals.

Visual, auditory, and olfactory stimuli influence food intake at all ages. There is a decrease in the sense of odor and taste changes caused by the deterioration of sensory functions in the elderly [

12]. In a study by Braun et al. comparing 30 elderly individuals over 59 years of age with a younger control group in terms of taste and odor, it was shown that taste and odor scores of elderly individuals were significantly reduced compared to youngs [

13]. Usually seen in up to 50% of elderly individuals, this loss of taste and smell can lead to a loss of appetite [

14]. By affecting the hedonistic development of food intake, age-related sensory impairments increase the risk of malnutrition by causing elderly individuals to give up eating or choose a monotonous diet [

15].

Figure 3 shows the sensory properties of the snack bars with different contents developed within the scope of this study. The flavor is defined as a combination of sensory stimuli produced by consuming food. In addition to affecting taste, sensory properties such as odor, appearance, and texture of food are considered to be important determinants of eating behaviors. The addition of pumpkin (P2) and date puree (D2) to the snack bars developed in this study resulted in a delicious product. Considering the general taste values of the samples determined sensually, the highest scores were obtained for bars with high levels of date puree (D2) and low levels of pumpkin puree (P1). In conclusion, in terms of general sensory properties, it is thought that snack bars containing pumpkin puree and date puree have high consumability compared to the others and can provide diversity in the diets of elderly individuals.

4.2. Nutritional Properties

The risk of malnutrition increases in elderly individuals when oral intake is reduced or in the presence of any risk factor that affects food intake and/or increases nutrient requirements [

2]. Caregivers need access to ideas and tools that can assist these elderly individuals to help this population overcome the challenges of preparing and consuming a nutritionally rich diet. Besides, one practical way to add nutritious foods to their diets is to prepare simple and nutritious snacks [

16]. In a study conducted by Leech et al., among US adults aged 65+, consumption of healthy snacks has been shown to contribute to higher protein, carbohydrate, and fat intake [

17]. Therefore, this study, it was aimed to develop a snack bar in the form of a bar containing collagen with a high level of softness, consumability, and nutritional value suitable for the consumption of the elderly.

Energy content of the bars, it is seen that D1 and D2 samples have the highest energy content. In a study conducted by Krok-Schoen and colleagues, it was found that the total energy intake of individuals aged 71 years and elderly from snacks during the day was 315 kcal/day [

18]. It is thought that these bars, which have an energy content of approximately 300-400 kcal per serving, can be an alternative snack, especially for elderly individuals who have difficulty providing adequate daily energy requirements. The biggest health concern in the aging population is to slow down the decline in muscle mass and strength and maintain a healthy body weight. Therefore, elderly individuals benefit from a slight increase in dietary protein intake [19, 20]. In a study conducted by Krok-Schoen and colleagues, it was found that the total protein intake of individuals aged 71 years and elderly from snacks during the day was 7.2 g/day [

18]. Costa and colleagues have also stated that their food supplement, specifically designed for the consumption of older individuals, contains 12.7 grams of protein per serving (30g) and provides a significant contribution to meeting their nutritional needs [

21]. According to the protein content of the snack bar samples in this study (6.8-8.8 grams of protein per serving), its inclusion in the daily diet of elderly individuals may contribute to supporting protein intake. In a study conducted by Nykänen et al., it is seen that regular use of snacks improves nutritional and functional status in elderly individuals [

22]. In addition, in elderly individuals, energy-rich snacks in small volumes are another way to cope with early satiety [

23]. Studies report that protein and micronutrients are among the nutrients associated with health risks related to inadequate intake in elderly [24, 25]. It is thought that the snack bars developed within the scope of the study may contribute to micronutrient intake. Aging and poor nutrition can also affect collagen levels in the body. According to the studies, it can be seen that functional collagen peptides are effective when taken between 2.5 and 15 grams per day [

26]. Furthermore, collagen peptides increase mobility, significantly reducing pain in osteoarthritis patients and functional joint pain [

27]. However, considering the amount of collagen used in the studies, the snack bars developed in this study have low collagen content. It is thought that the bar samples may contribute to daily collagen intake when included as a supplement to an adequate and balanced diet, but not alone.

5. Conclusions

Nutritional needs change by age and some nutrients, vitamins, and minerals become more important for muscle and bone health. Eating a variety of foods from all food groups is important to achieve optimal health and to help ensure that individuals get the nutrients they need. Guiding elderly individuals to make the right food choices will increase nutrient intake and lead to positive health outcomes. Since an age-related decline in appetite is often observed in this age group, offering small meals or snacks with improved sensory characteristics, rich in nutrients and consumables, will help improve food intake. However, the inclusion of collagen peptides, a nutraceutical whose use has become widespread in recent years due to its health benefits, in the diet of elderly individuals will improve the quality of life during aging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E and T. İ. N; methodology, H. F. and T. İ. N; software, B. N.; validation, T. İ. N; formal analysis, T. İ. N; investigation, H.E. and T. İ. N; resources, H. F. and H. E.; data curation, H.E and B. N.; writing—original draft preparation, T. İ. N.; writing—review and editing, H.E., B. N. and F. E.; visualization, T.İ.N.; supervision, H.E. and H. F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethical approval of the study was obtained with the decision of Sivas Cumhuriyet University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Social and Human Sciences Board dated 29.04.2022 and numbered E-60263016-050.06.04-159557.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Arowosola, T.A.; Makanjuola, O.O.; Olagunju-Yusuf, O.F. The Role of Food in the Health Management of Geriatrics. In: Babalola, O.O., Ayangbenro, A.S., and Ojuederie, O.B. (Eds) Food Security and Safety Volume 2. Springer 2023 Cham.

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A. M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C. C.; Sobotka, L.; van Asselt, D.; Wirth, R.; Bischoff, S.C. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38, 10–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, J.M.; Shikany, J.M.; Thomson, C.A. The role of dietary protein intake in the prevention of sarcopenia of aging. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 2013, 28, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Cruz, G.; León-López, A.; Cruz-Gómez, V.; Jiménez-Alvarado, R.; Aguirre-Álvarez, G. Collagen Hydrolysates for Skin Protection: Oral Administration and Topical Formulation. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porfírio, E.; Fanaro, G. Collagen supplementation as a complementary therapy for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia 2016, 19, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraç, M.G.; Dedebaş, T.; Hastaoğlu, E.; Arslan, E. Influence of using scarlet runner bean flour on the production and physicochemical, textural, and sensorial properties of vegan cakes: WASPAS-SWARA techniques. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 2022, 27, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, A.; Ares, F.; Ares, G. Sensory shelf-life estimation: A review of current methodological approaches. Food Research International 2012, 49, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L; Yoon, K. Methods for Multiple Attribute Decision Making. In: Hwang, C.L. and Yoon, K. (Eds). Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications A State of the Art Survey. Springer 1981 Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 58–191.

- Li, X.; Wang, K.; Liu, L.; Xin, J.; Yang, H.; Gao, C. Application of the entropy weight and TOPSIS method in safety evaluation of coal mines. Procedia Engineering 2011, 26, 2085–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H. Y.; Zhang, P. P.; Wang, X. W. Presbyphagia: Dysphagia in the elderly. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 2023, 11, 2363–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivayam-MacDonald, A.M.; Morrison, J.M.; Steele, C.M.; Keller, H. How swallow pressures and dysphagia affect malnutrition and mealtime outcomes in long-term care. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S.; Yavuz, C. Yaşlılık ve Beslenme: Elderly and Nutrition. In: Say Şahin, D. (Ed), Yaşlanmaya Sağlık Sosyolojisi Perspektifinden Multidisipliner Yaklaşımlar, 1st ed. Ekin Yayınevi 2020 pp. 175–190.

- Braun, T.; Doerr, J.M.; Peters, L.; Viard, M.; Reuter, I.; Prosiegel, M.; Weber, S.; Yeniguen, M.; Tschernatsch, M.; Gerriets, T.; Juenemann, M.; Huttner, H.B.; Hamzic, S. Age-related changes in oral sensitivity, taste and smell. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarya, S.; Singh, K.; Sabharwal, M. Changes during aging and their association with malnutrition. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics 2015, 6, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, V.D.; Pellizzari, L.; Corrà, L.; Fontana, G. The anorexia of aging: impact on health and quality of life. Geriatric Care 2019, 4, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoraie, N.M.; Saqaan, R.; Alharthi, R.; Alamoudi, A.; Badh, L.; Shatwan, I.M. Snacking patterns throughout the life span: potential implications on health. Nutrition Research 2021, 91, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leech, R.M.; Worsley, A.; Timperio, A.; McNaughton, S.A. Understanding meal patterns: Definitions, methodology and impact on nutrient intake and diet quality. Nutrition Research Reviews 2015, 28, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Luo, M.; Kelly, O.J.; Taylor, C.A. Nutrient intakes from meals and snacks differ with age in middle-aged and older Americans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, N.; Meram, C.; Bandara, N.; Wu, J. Protein and peptides for elderly health. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology 2018, 112, 265–308. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, D.K.; Nicklas, B.J.; Ding, J.; Harris, T.B.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Newman, A.B.; Lee, S.L.; Sahyoun, N.R.; Visser, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B. Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 87, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.M.B; Sakon, P.O.R.; Paula, H.A.A.; Pinto, M.S.; Sant’Anna, M.S.L.; Araújo, T.F.; Minim, V.P.R. Protein and sensory quality of a food supplement formulated for the elderly. Acta Alimentaria 2014, 43, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, I.; Törrönen, R.; Schwab, U. Dairy-based and energy-enriched berry-based snacks improve or maintain nutritional and functional status in older people in home Care. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 2018, 22, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Jadczak, A.D.; Visvanathan, R. Anorexia of aging - An updated short review. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 2019, 23, 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, K.L. Tucker, K.L. High risk nutrients in the aging population. In: Bales, C., Locher, J., Saltzman, E. (eds). Handbook of clinical nutrition and aging. 3rd ed. Springer, 2015 pp. 335–53.

- Wallace, T.C.; Frankenfeld, C.L.; Frei, B.; Shah, A.V.; Yu, C.R.; van Klinken, B.J.; Adeleke, M. Multivitamin/multimineral supplement use is associated with increased micronutrient intakes and biomarkers and decreased prevalence of inadequacies and deficiencies in middle-aged and older adults in the United States. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics 2019, 38, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, C.; Leser, S.; Oesser, S. Significant amounts of functional collagen peptides can be incorporated in the diet while maintaining indispensable amino acid balance. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, A.; Novelli, A. Sarcopenia in the elderly: from clinical aspects to therapeutic options. Geriatric Care 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).