Submitted:

25 July 2023

Posted:

26 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Burden of Cervical Cancer in Bucharest Oncology Institute

3.2. Knowledge about Cervical Cancer Prevention, Early Detection Methods and Health-Care Access among Targeted Population

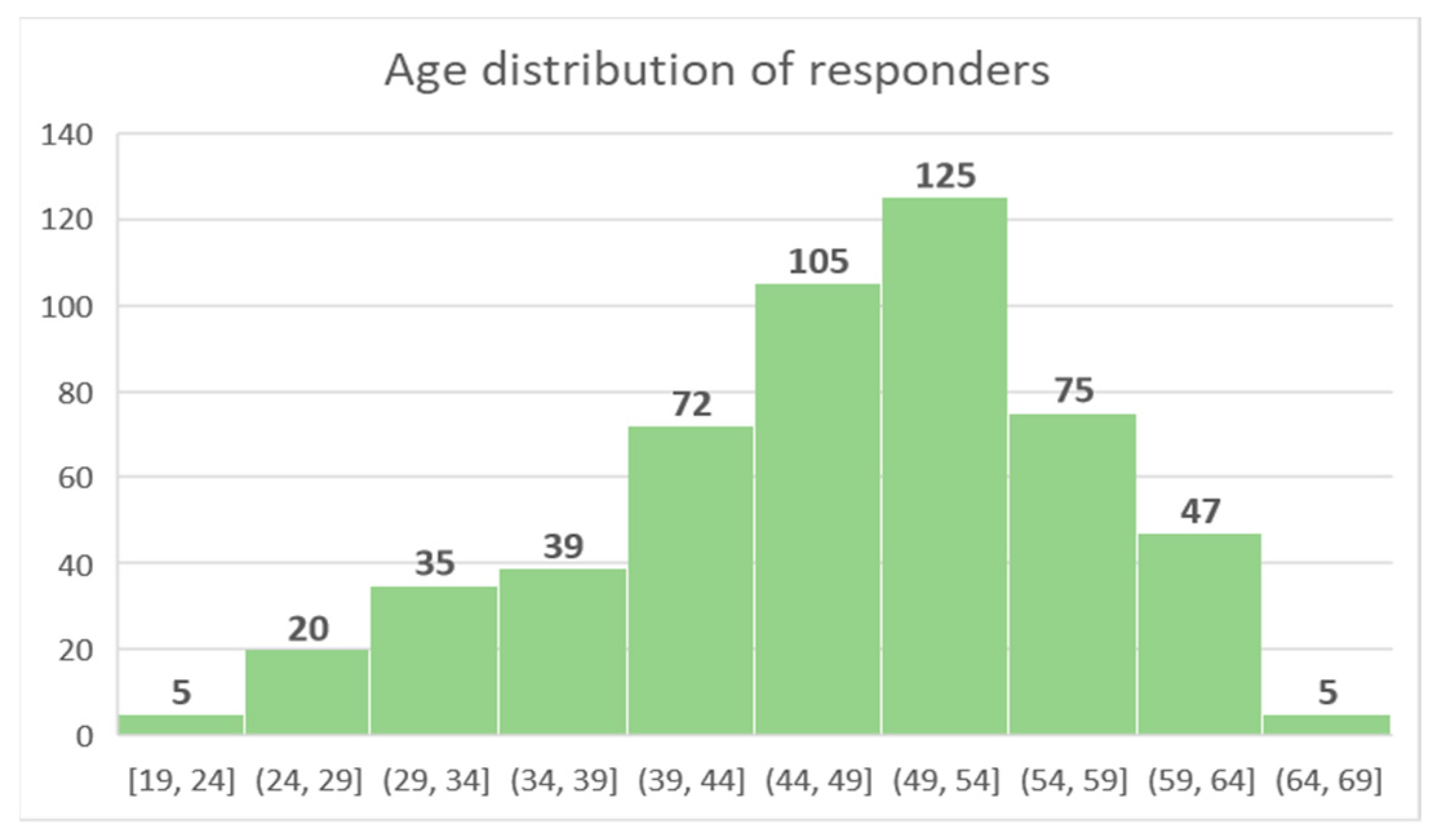

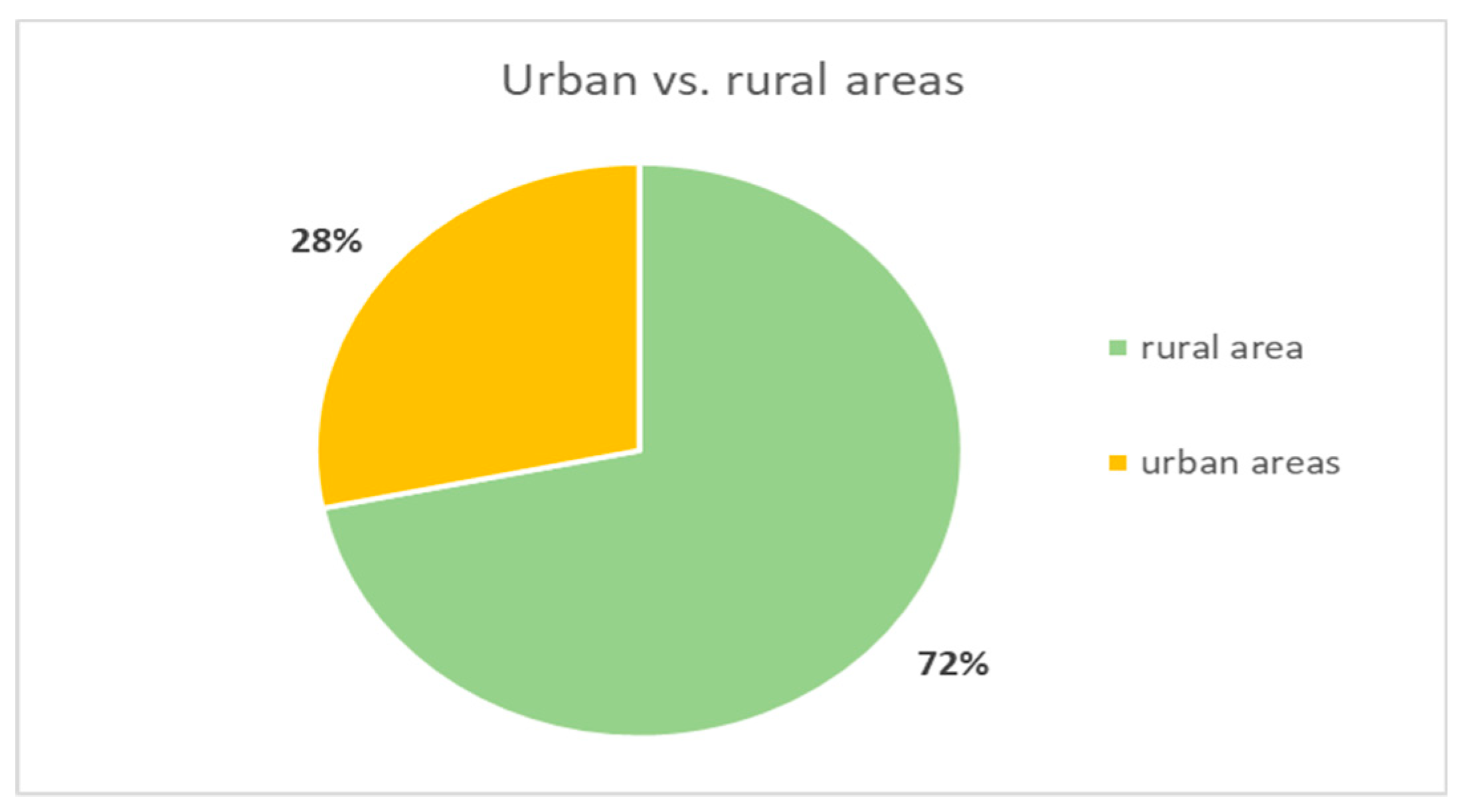

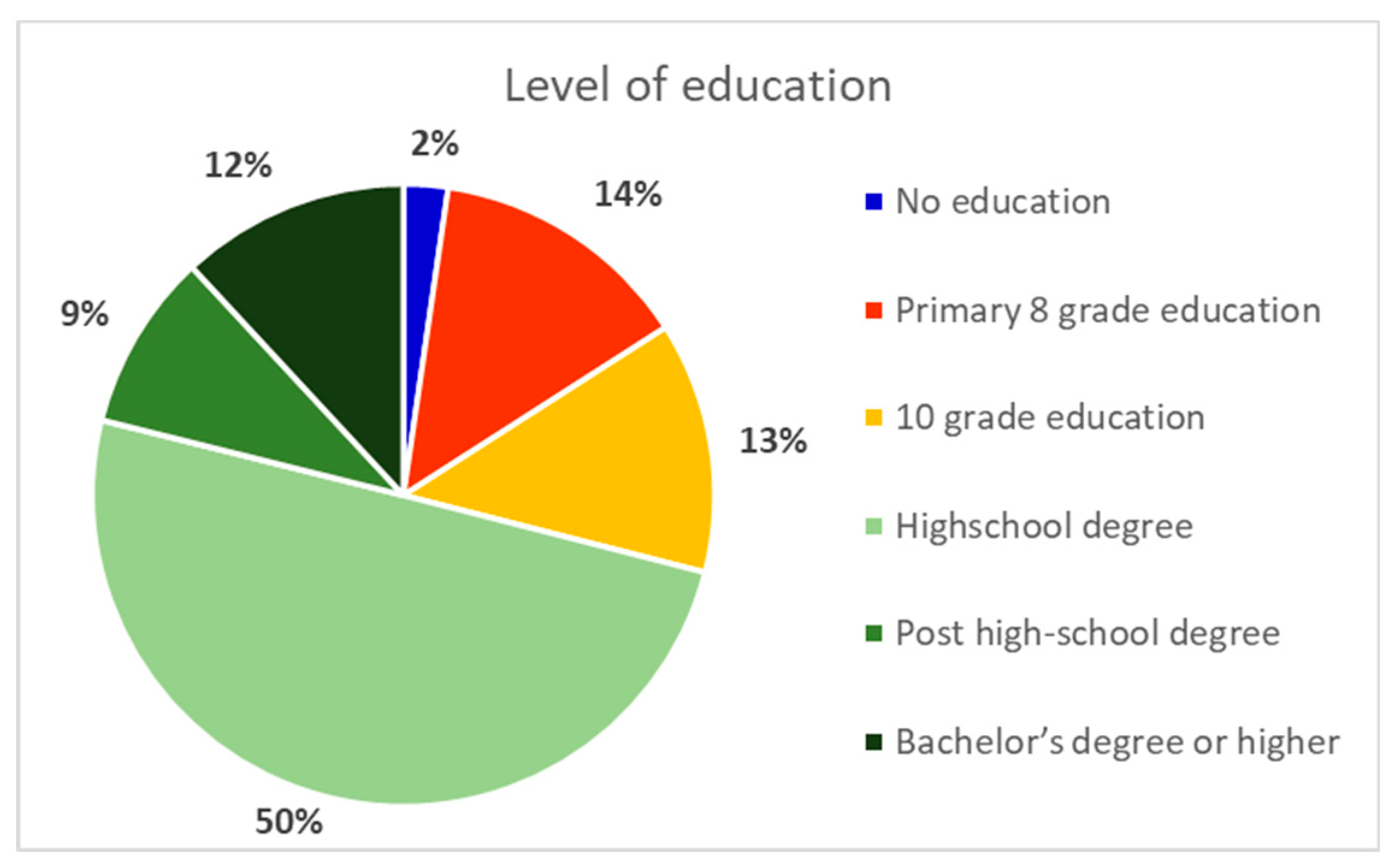

3.2.1. Demographic Data of Responders

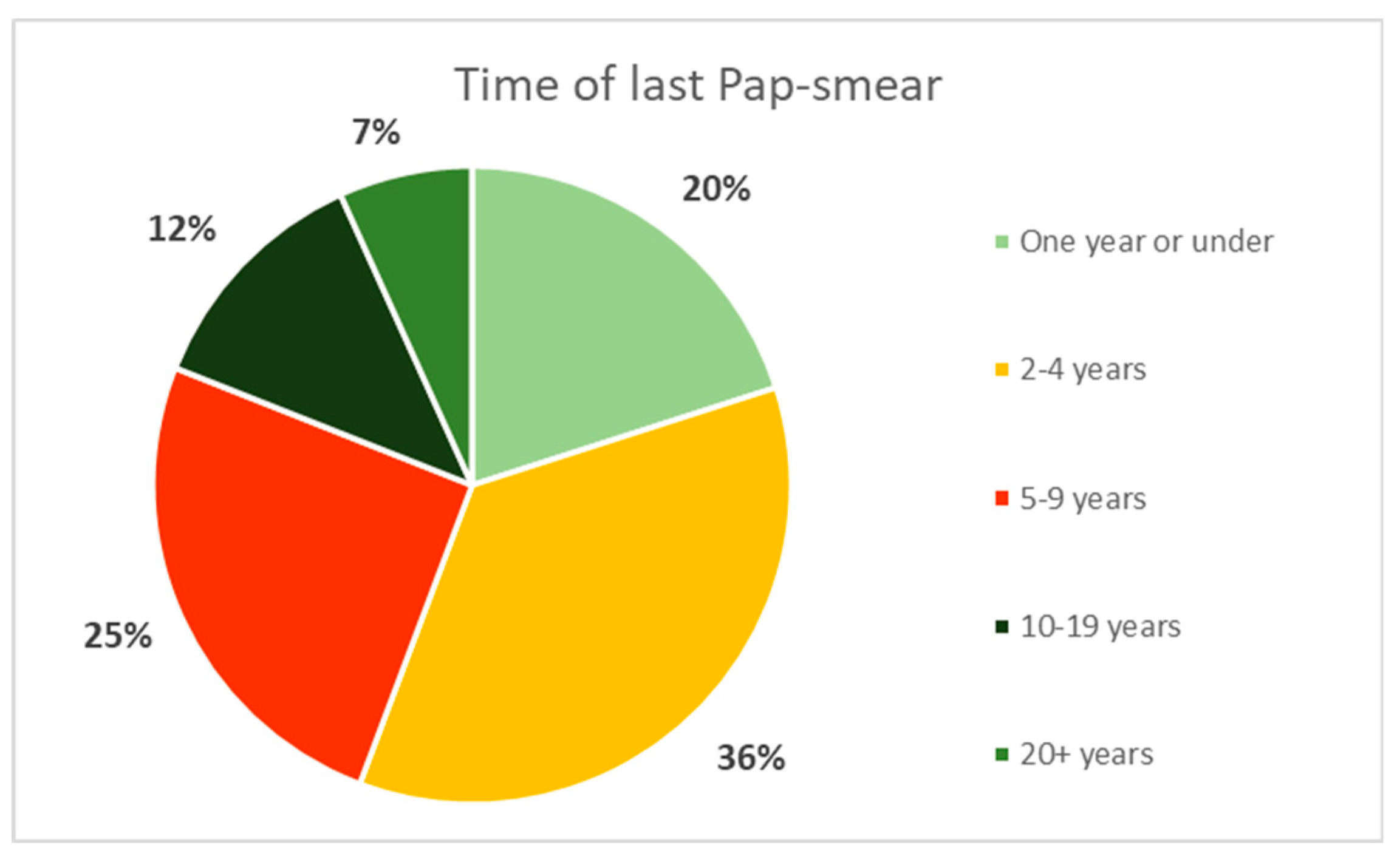

3.2.2. Access to Cervical Cancer Specific Preventive/Diagnostic Methods

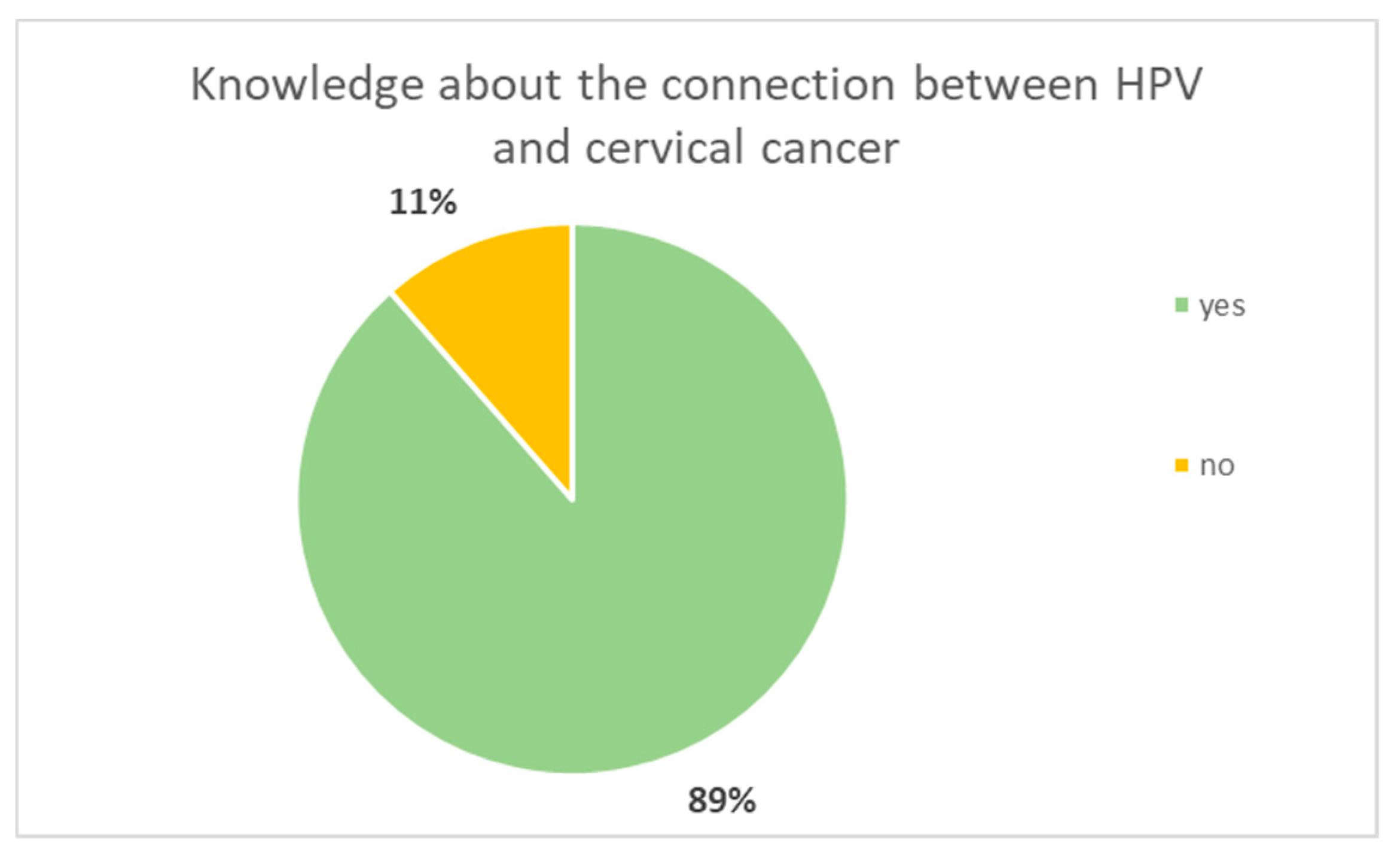

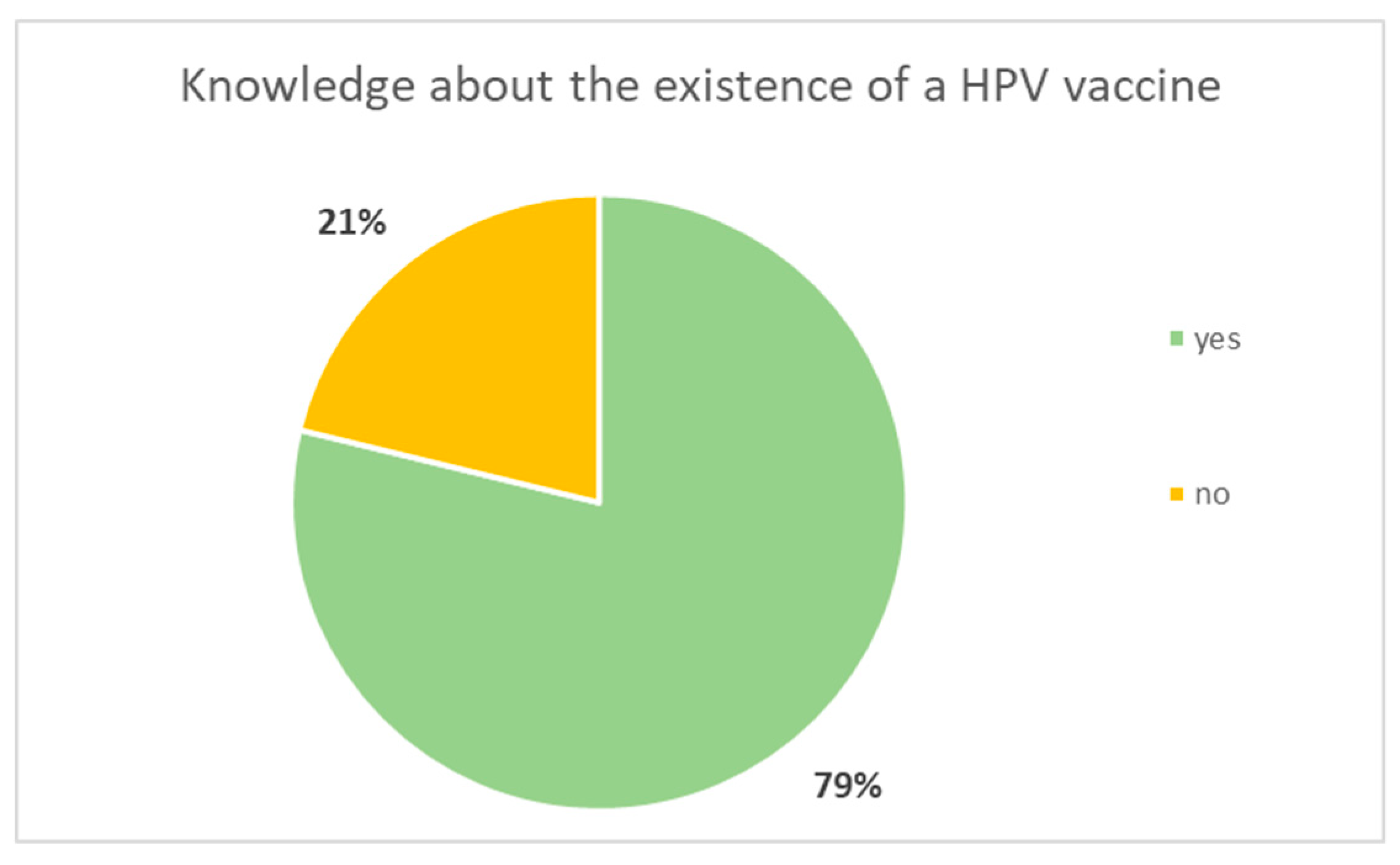

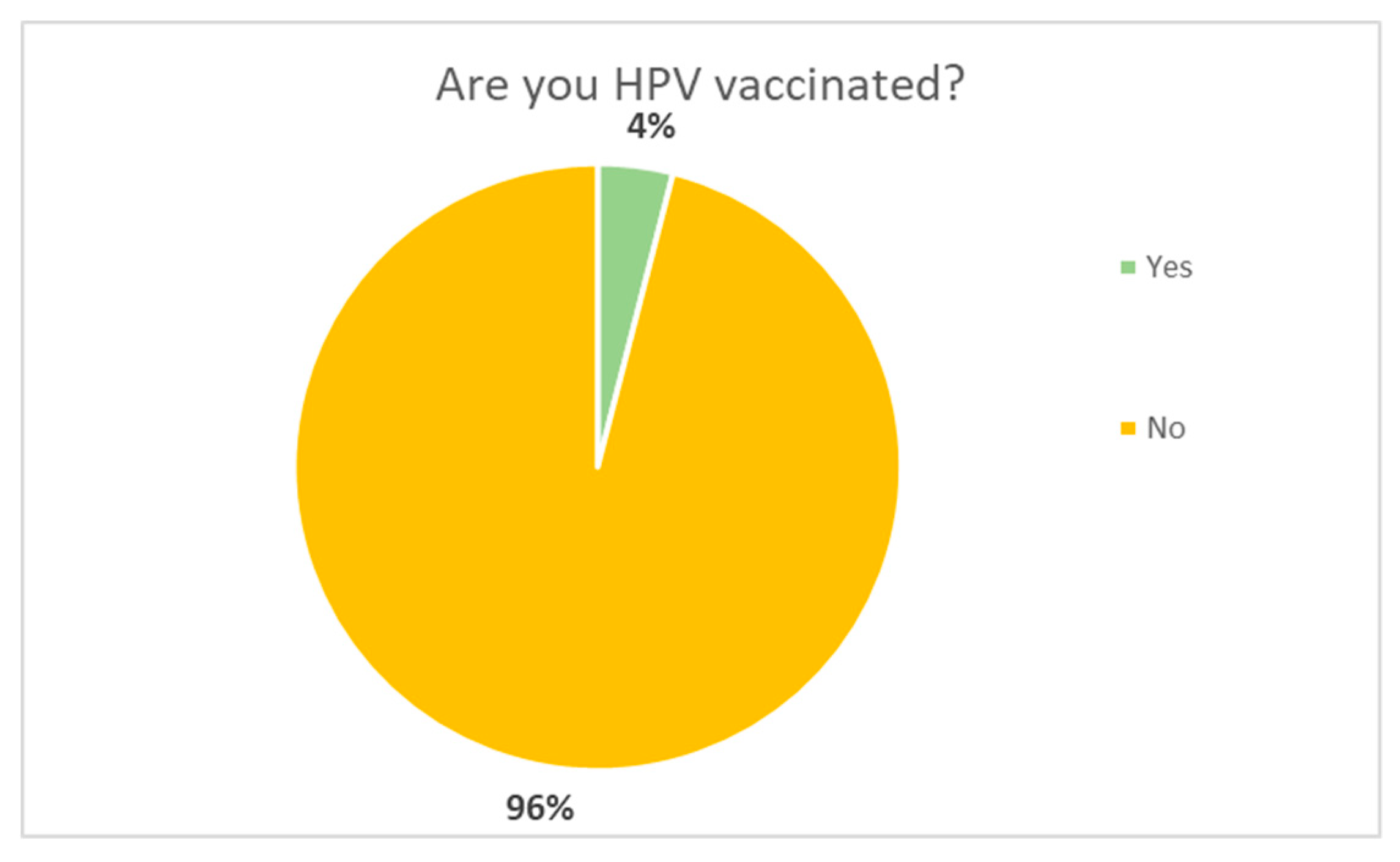

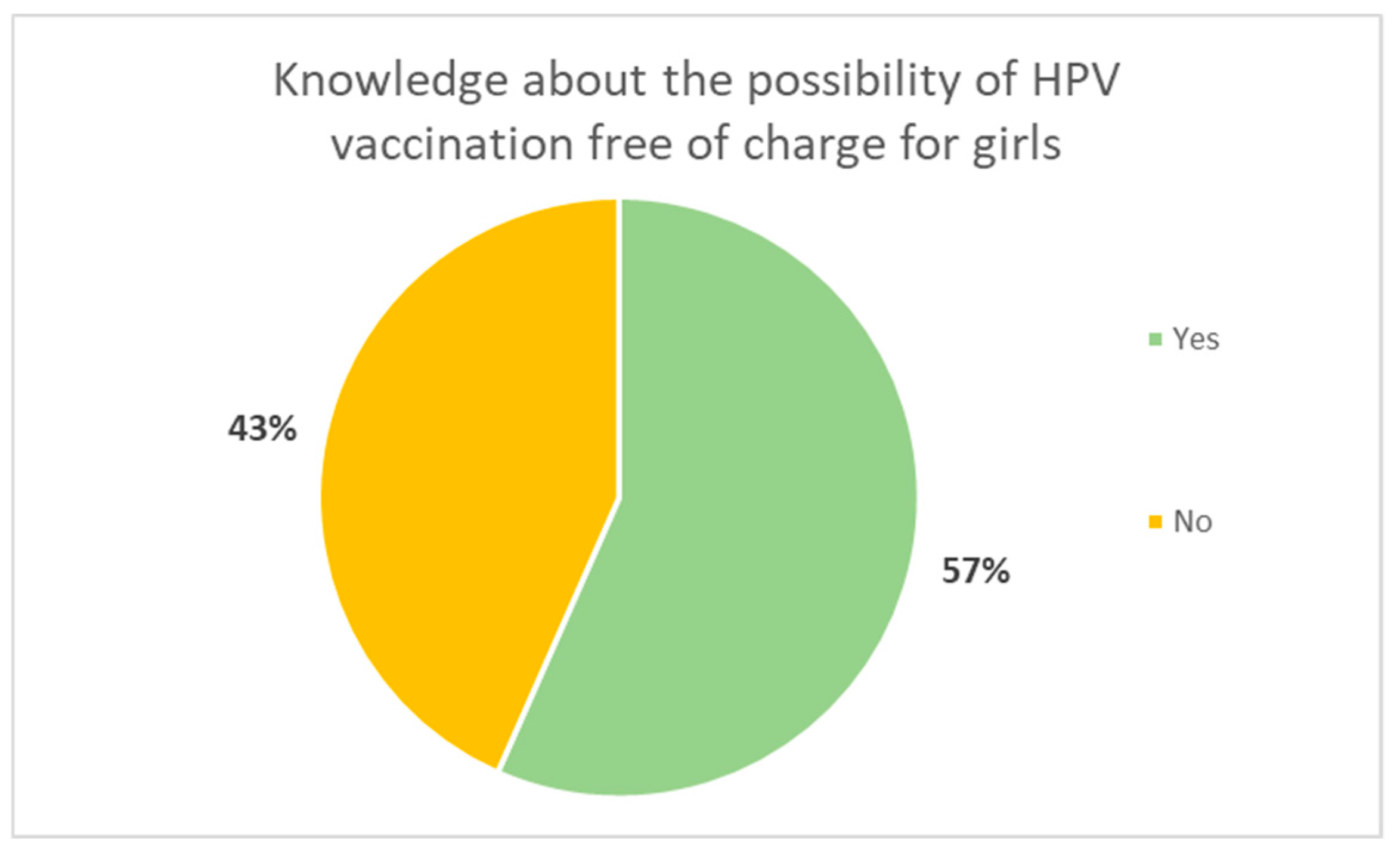

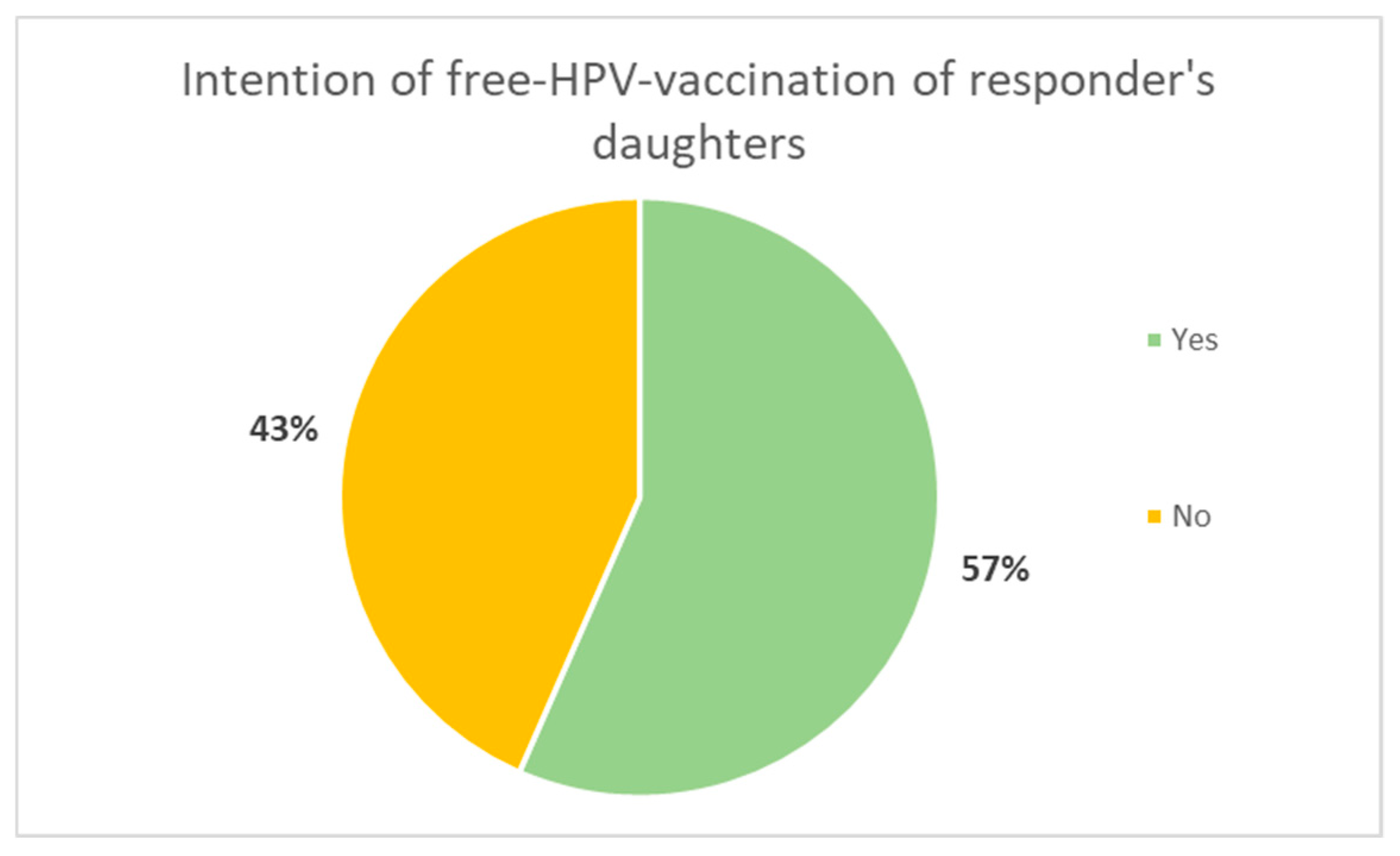

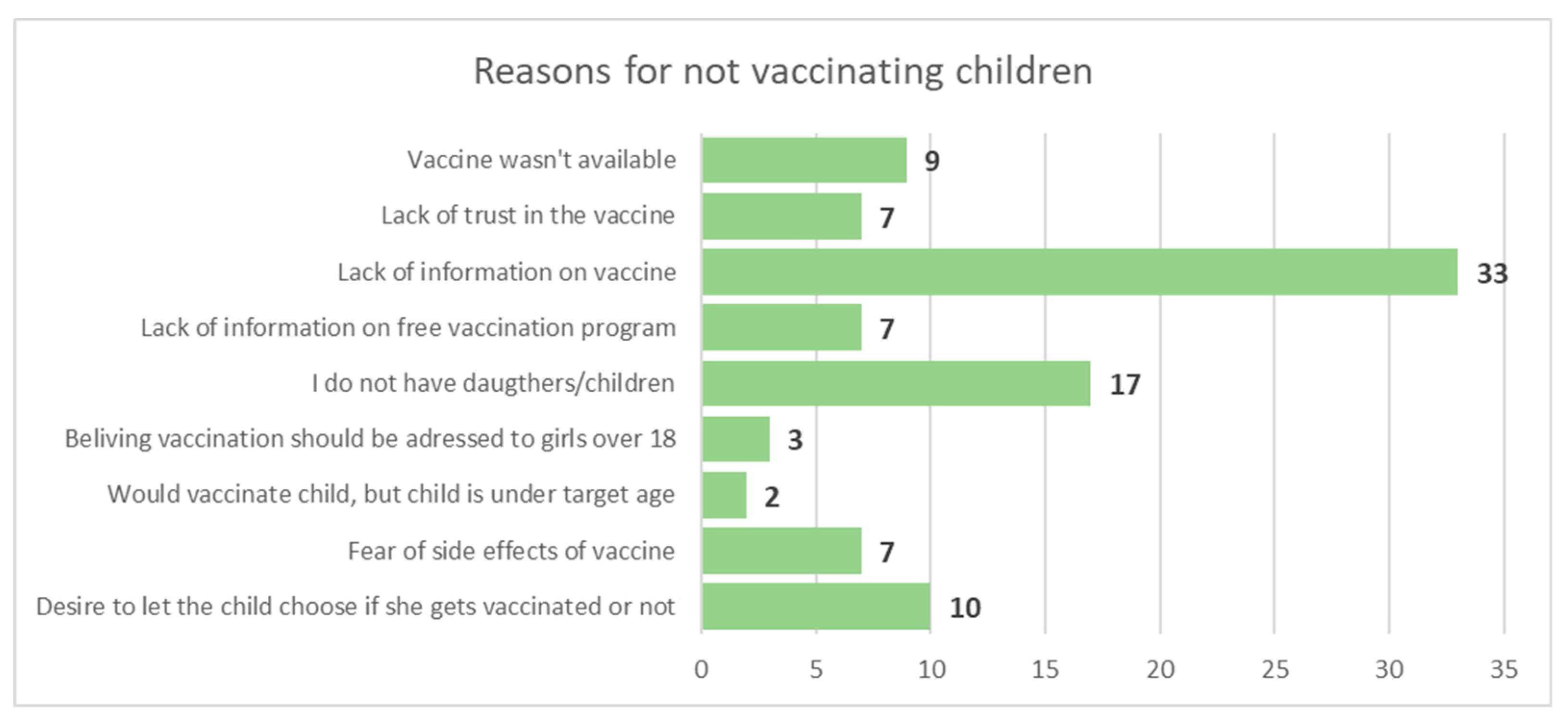

3.2.3. Knowledge about HPV and HPV-Vaccination, Access to Vaccine

4. Discussion

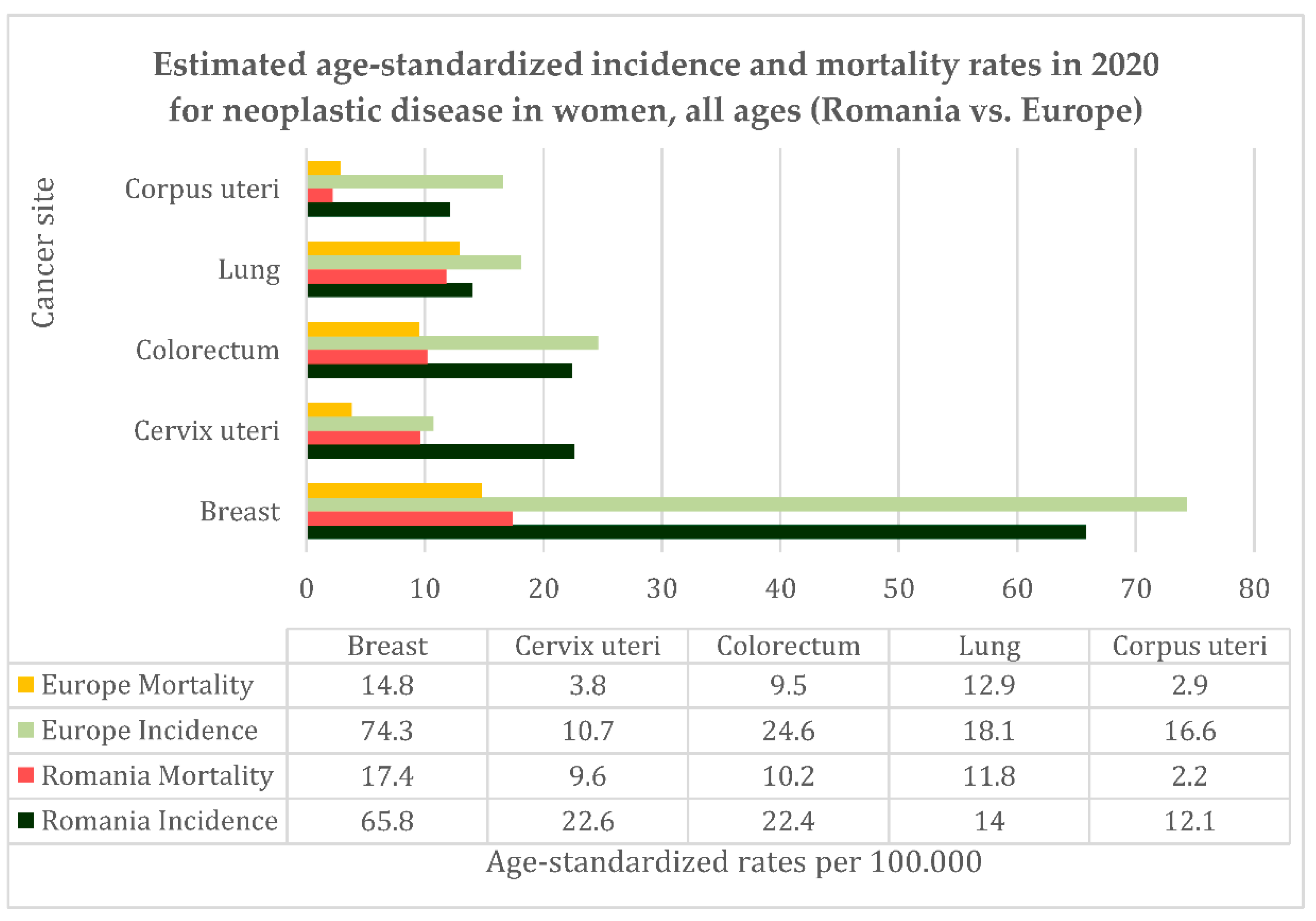

4.1. Cervical Cancer in Romania Vs. Europe/World – Current Situation, Trends, Incidence, and Mortality

4.2. Cervical Cancer Screening Program in Romania

4.3. HPV Vaccination Program in Romania

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Todor, R.D.; Bratucu, G.; Moga, M.A.; Candrea, A.N.; Marceanu, L.G.; Anastasiu, C.V. Challenges in the Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Romania. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/home (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Agache, A.; Mustãåea, P.; Mihalache, O.; Bobîrca, F.T.; Georgescu, D.E.; Jauca, C.M.; Bîrligea, A.; Doran, H.; Pãtraaecu, T. Diabetes Mellitus as a Risk-Factor for Colorectal Cancer Literature Review-Current Situation and Future Perspectives. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2018, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. WHO Guidance Note: Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control: A Healthier Future for Girls and Women. 2013.

- Gaffney, D.K.; Hashibe, M.; Kepka, D.; Maurer, K.A.; Werner, T.L. Too Many Women Are Dying from Cervix Cancer: Problems and Solutions. Gynecol Oncol 2018, 151, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simms, K.T.; Steinberg, J.; Caruana, M.; Smith, M.A.; Lew, J. Bin; Soerjomataram, I.; Castle, P.E.; Bray, F.; Canfell, K. Impact of Scaled up Human Papillomavirus Vaccination and Cervical Screening and the Potential for Global Elimination of Cervical Cancer in 181 Countries, 2020–2099: A Modelling Study. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Romania’s Income Level. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=RO-XT (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Institutul national de statistica Statistici Isnne. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Trifanescu, O.G.; Gales, L.; Bacinschi, X.; Serbanescu, L.; Georgescu, M.; Sandu, A.; Michire, A.; Anghel, R. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Treatment and Oncologic Outcomes for Cancer Patients in Romania. In Vivo (Brooklyn) 2022, 36, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Population (% of Total Population) | Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?view=chart (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- European Commission Health Europa. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-12/2022_healthatglance_rep_en_0.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report WORLD. Available online: www.hpvcentre.net/statistics/report/XWX.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Ilisiu, M.B.; Hashim, D.; Andreassen, T.; Støer, N.C.; Nicula, F.; Weiderpass, E. HPV Testing for Cervical Cancer in Romania: High-Risk HPV Prevalence among Ethnic Subpopulations and Regions. Ann Glob Health 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, A.; Ronco, G. Description of the National Situation of Cervical Cancer Screening in the Member States of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 2685–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, I.L.G.; Baban, A.; Balabanova, D.; Panayotova, Y.; Bradley, J. Providers’ Constructions of the Role of Women in Cervical Cancer Screening in Bulgaria and Romania. Soc Sci Med 2006, 63, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Raifu, A.O.; Weiderpass, E.; Bray, F.; Anttila, A. Trends of Cervical Cancer Mortality in the Member States of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 2640–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirson, L.; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; Ciliska, D.; Warren, R. Screening for Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst Rev 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.E.L.; Zielonke, N.; Gini, A.; Anttila, A.; Segnan, N.; Vokó, Z.; Ska Ivanu, U.; Mckee, M.; De Koning, H.J.; De Kok, I.M.C.M. Effect of Organised Cervical Cancer Screening on Cervical Cancer Mortality in Europe: A Systematic Review. Eur J Cancer 2020, 127, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtunescu, F.; Bohiltea, R.E.; Neacsu, A.; Grigoriu, C.; Pop, C.S.; Bacalbasa, N.; Ducu, I.; Iordache, A.M.; Costea, R.V. Cervical Cancer Mortality in Romania: Trends, Regional and Rural–Urban Inequalities, and Policy Implications. Medicina (B Aires) 2022, 58, 18. [CrossRef]

- EU Commission: Council Recommendation of 2 December... - Google Academic. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Off.+J.+Eur.+Union&title=Council+recommendation+of+2+December+2003+on+cancer+screening+(2003/878/EC)&volume=327&publication_year=2003&pages=34-38& (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Ponti, A.; Anttila, A.; Ronco, G.; Senore, C. Cancer Screening in the European Union (2017). Report on the Implementation of the Council Recommendation on Cancer Screening. Cancer screening in the European Union (2017). Report on the implementation of the council recommendation on cancer screening. 2017.

- Nicula, F. Al; Anttila, A.; Neamtiu, L.; Žakelj, M.P.; Tachezy, R.; Chil, A.; Grce, M.; Kesić, V. Challenges in Starting Organised Screening Programmes for Cervical Cancer in the New Member States of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 2679–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtunescu, F.; Bohiltea, R.E.; Voinea, S.; Georgescu, T.A.; Munteanu, O.; Neacsu, A.; Pop, C.S. Breast Cancer Mortality Gaps in Romanian Women Compared to the EU after 10 Years of Accession: Is Breast Cancer Screening a Priority for Action in Romania? (Review of the Statistics). Exp Ther Med 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfström, K.M.; Arnheim-Dahlström, L.; Von Karsa, L.; Dillner, J. Cervical Cancer Screening in Europe: Quality Assurance and Organisation of Programmes. Eur J Cancer 2015, 51, 950–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtyla, C.; Janik-Koncewicz, K.; La Vecchia, C. Cervical Cancer Mortality in Young Adult European Women. Eur J Cancer 2020, 126, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altobelli, E.; Lattanzi, A. Cervical Carcinoma in the European Union: An Update on Disease Burden, Screening Program State of Activation, and Coverage as of March 2014. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesic, V. Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A Challenge for the Future. Vaccine 2013, 31, vii–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicula, F. Al; Anttila, A.; Neamtiu, L.; Žakelj, M.P.; Tachezy, R.; Chil, A.; Grce, M.; Kesić, V. Challenges in Starting Organised Screening Programmes for Cervical Cancer in the New Member States of the European Union. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 2679–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eniu, A.; Dumitraşcu, D.; Geanta, M. Romania, Attempting to Catch up the European Standards of Care for Cancer Patients. Cancer Care Ctries. Soc. Transit. Individ. Care Focus 2016, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romania’s National Cancer Plan. Available online: https://www.ms.ro/media/documents/Planul_Na%C8%9Bional_de_Combatere_%C8%99i_Control_al_Cancerului_RIQiTXG.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Sănătății, M. ACTE ALE ORGANELOR DE SPECIALITATE ALE ADMINISTRAȚIEI PUBLICE CENTRALE O R D I N Privind Aprobarea Normelor Tehnice de Realizare a Programelor Naționale de Sănătate Publică*) – order given by the Romanian Ministry of Health.

- Official Statistics in Romania | National Institute of Statistics. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/en/content/official-statistics-romania (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Romania’s Cervical Cancer Country Profile. Available online: https://www.iccp-portal.org/system/files/plans/cervical-cancer-rou-2021-country-profile-en.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Hajioff, S.; McKee, M. The Health of the Roma People: A Review of the Published Literature. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978) 2000, 54, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, T.; Melnic, A.; Figueiredo, R.; Moen, K.; Şuteu, O.; Nicula, F.; Ursin, G.; Weiderpass, E. Attendance to Cervical Cancer Screening among Roma and Non-Roma Women Living in North-Western Region of Romania. Int J Public Health 2018, 63, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, T.; Weiderpass, E.; Nicula, F.; Suteu, O.; Itu, A.; Bumbu, M.; Tincu, A.; Ursin, G.; Moen, K. Controversies about Cervical Cancer Screening: A Qualitative Study of Roma Women’s (Non) Participation in Cervical Cancer Screening in Romania. Soc Sci Med 2017, 183, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada, C. Sexual Behavior and Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Cross-Sectional Study in Romania. Reprod Health 2014, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balazsi, R.; Bradley, J.; Szentagotai-Tatar, A. Psychosocial and Health System Dimensions of Cervical Screening in Romania OPEN RES View Project a Computational Distributed System to Support the Treatment of Patients with Major Depression (Help4Mood). View Project; 2000.

- Todorova, I.; Baban, A.; Alexandrova-Karamanova, A.; Bradley, J. Inequalities in Cervical Cancer Screening in Eastern Europe: Perspectives from Bulgaria and Romania. Int J Public Health 2009, 54, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherghe, M.; Mutuleanu, M.D.; Stanciu, A.E.; Irimescu, I.; Lazar, A.; Bacinschi, X.; Anghel, R.M. Quantitative Analysis of SPECT-CT Data in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients—The Clinical Significance. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pãtrascu, Tr.; Doran, H.; Catrina, E.; Mihalache, O.; Degeratu, D.; Predescu, G. Tumori Sincrone Ale Tractului Digestiv. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2010, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Cirimbei, C.; Rotaru, V.; Radu, M.; Cirimbei, S.E. Association of Colorectal Cancer and GIST Tumors - A Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenge: A Case Report. Int. Res. J. Med. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, L.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, S.; Chitoran, E.; Gales, L.; Luca, D.C.; Ionescu, S.; Tanase, B.; Ginghina, O.; Alecu, M.; et al. Simultaneous Approach of Colo-Rectal and Hepatic Lesions in Colo-Rectal Cancers with Liver Metastasis - A Single Oncological Center Overview. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2023, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programul National de Oncologie. Available online: http://www.casan.ro/page/programul-national-de-oncologie.html (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Cirimbei, C.; Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, S. Laparoscopic Approach in Abdominal Oncologic Pathology, Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week, Athens, Greece, 25-27 September 2018. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000471903700043 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Rotaru, V.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, C.; Cirimbei, S.; Simion, L. Preservation of Sensory Nerves During Axillary Lymphadenectomy, Proceedings of the 35th Balkan Medical Week, Athens, Greece, 25-27 September 2018. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000471903700045 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Gheghe, M.; Bordea, C.; Blidaru, Al. Clinical Significance of the Lymphoscintigraphy in the Evaluation of Non-Axillary Sentinel Lymph Node Localization in Breast Cancer. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2015, 110, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Simion, L.; Ionescu, S.; Chitoran, E.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, C.; Madge, O.L.; Nicolescu, A.C.; Gherghe, M.; Tanase, B.; Andreescu, I.G.D.; et al. Indocyanine Green (Icg) And Colorectal Surgery: A Literature Review on Qualitative and Quantitative Methods of Usage. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bordea, C.; Plesca, M.; Condrea, I.; Gherghe, M.; Gociman, A.; Blidaru, A. Occult Breast Lesion Localization and Concomitant Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Early Breast Cancer (SNOLL). Chirurgia (Bucur) 2012, 107, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, L.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, C.; Stefan, D.C.; Gherghe, M.; Ionescu, S.; Tanase, B.C.; Luca, D.C.; Gales, L.N.; Chitoran, E. Analysis of Efficacy-To-Safety Ratio of Angiogenesis-Inhibitors Based Therapies in Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanian Ministry of Health Vaccinarea Populației La Vârstele Prevăzute În Calendarul Național de Vaccinare.

- Simion, L.; Chitoran, E.; Cirimbei, C.; Stefan, D.-C.; Neicu, A.; Tanase, B.; Ionescu, S.O.; Luca, D.C.; Gales, L.; Gheorghe, A.S.; et al. A Decade of Therapeutic Challenges in Synchronous Gynecological Cancers from the Bucharest Oncological Institute. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, C.; Maier, T.; Neagu, C.E.; Vlədəreanu, R. Romanian Adolescents’ Knowledge and Attitudes towards Human Papillomavirus Infection and Prophylactic Vaccination. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2015, 195, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabina Cornelia Manolescu, L.; Iulia Mitran, C.; Irina Mitran, M.; Roxana Georgescu, S.; Tampa, M.; Suciu, I.; Suciu, G.; Preda, M.; Cerasella Dragomirescu, C.; Loredana Popa, G.; et al. Knowledge, attitude and perception towards the hpv infection and immunization among romanian medical students. ROMANIAN ARCHIVES OF MICROBIOLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY 80, 22–34.

- Pent¸a, M.A.P.; Ba, A. Mass Media Coverage of HPV Vaccination in Romania: A Content Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Manolescu, L.S.C.; Zugravu, C.; Zaharia, C.N.; Dumitrescu, A.I.; Prasacu, I.; Radu, M.C.; Letiția, G.D.; Nita, I.; Cristache, C.M.; Gales, L.N. Barriers and Facilitators of Romanian HPV (Human Papillomavirus) Vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wu, B.; Dai, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Mei, K.; Wu, Z. Gender Differences in Knowledge and Attitude towards HPV and HPV Vaccine among College Students in Wenzhou, China. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessl, C.L.; Christianson, B.; Hanson, K.E.; Polter, E.J.; Olson, S.C.; Boyce, T.G.; Dunn, D.; Williams, C.L.; Belongia, E.A.; McLean, H.Q.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Beliefs and Practice Characteristics in Rural and Urban Adolescent Care Providers. BMC Public Health 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degarege, A.; Krupp, K.; Fennie, K.; Li, T.; Stephens, D.P.; Marlow, L.A.V.; Srinivas, V.; Arun, A.; Madhivanan, P. Urban-Rural Inequities in the Parental Attitudes and Beliefs Towards Human Papillomavirus Infection, Cervical Cancer, and Human Papillomavirus Vaccine in Mysore, India. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2018, 31, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P. jun; O’Halloran, A.; Kennedy, E.D.; Williams, W.W.; Kim, D.; Fiebelkorn, A.P.; Donahue, S.; Bridges, C.B. Awareness among Adults of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases and Recommended Vaccinations, United States, 2015. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Eid, H.; Assaf, A.M.; Abdaljaleel, M.; Al-Abbadi, M.; Mahafzah, A. Attitude towards HPV Vaccination and the Intention to Get Vaccinated among Female University Students in Health Schools in Jordan. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, G.L.; Muntean, A.A.; Muntean, M.M.; Popa, M.I. Knowledge and Attitudes on Vaccination in Southern Romanians: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Mullen, J.; Smith, D.; Kotarba, M.; Kaplan, S.J.; Tu, P. Healthcare Providers’ Vaccine Perceptions, Hesitancy, and Recommendation to Patients: A Systematic Review. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Fabio, A. Literature Review of HPV Vaccine Delivery Strategies: Considerations for School- and Non-School Based Immunization Program. Vaccine 2014, 32, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Mullen, J.; Smith, D.; Kotarba, M.; Kaplan, S.J.; Tu, P. Healthcare Providers’ Vaccine Perceptions, Hesitancy, and Recommendation to Patients: A Systematic Review. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliusi, S.R.; Aguado, M.T. Efficacy and Other Milestones for Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Introduction. Vaccine 2004, 23, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrjänen, K.J.; Pyrhönen, S.; Syrjänen, S.M.; Lamberg, M.A. Immunohistochemical Demonstration of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Antigens in Oral Squamous Cell Lesions. British Journal of Oral Surgery 1983, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pytynia, K.B.; Dahlstrom, K.R.; Sturgis, E.M. Epidemiology of HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer. Oral Oncol 2014, 50, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, T.; Bruce, J.; Yip, K.W.; Liu, F.F. HPV Associated Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2016, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, S. V.; Bruce, J.P.; O’Sullivan, B.; Pugh, T.J.; Xu, W.; Yip, K.W.; Liu, F.F. Human Papillomavirus Genotype Association with Survival in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol 2016, 2, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahoud, J.; Semaan, A.; Chen, Y.; Cao, M.; Rieber, A.G.; Rady, P.; Tyring, S.K. Association between β-Genus Human Papillomavirus and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Immunocompetent Individuals-a Meta-Analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2016, 152, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.; Manders, P.; Earls, P.; Epstein, R.J. Papillomavirus-Associated Squamous Skin Cancers Following Transplant Immunosuppression: One Notch Closer to Control. Cancer Treat Rev 2014, 40, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandolin, L.; Borsetto, D.; Fussey, J.; Da Mosto, M.C.; Nicolai, P.; Menegaldo, A.; Calabrese, L.; Tommasino, M.; Boscolo-Rizzo, P. Beta Human Papillomaviruses Infection and Skin Carcinogenesis. Rev Med Virol 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampa, M.; Mitran, C.I.; Mitran, M.I.; Nicolae, I.; Dumitru, A.; Matei, C.; Manolescu, L.; Popa, G.L.; Caruntu, C.; Georgescu, S.R. The Role of Beta HPV Types and HPV-Associated Inflammatory Processes in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Immunol Res 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.A.; O’Rorke, M.A.; Wilson, R.; Jamison, J.; Gavin, A.T. HPV Prevalence and Type-Distribution in Cervical Cancer and Premalignant Lesions of the Cervix: A Population-Based Study from Northern Ireland. J Med Virol 2016, 88, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condrat, C.E.; Filip, L.; Gherghe, M.; Cretoiu, D.; Suciu, N. Maternal HPV Infection: Effects on Pregnancy Outcome. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souho, T.; Benlemlih, M.; Bennani, B. Human Papillomavirus Infection and Fertility Alteration: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zullo, F.; Fiano, V.; Gillio-Tos, A.; Leoncini, S.; Nesi, G.; Macrì, L.; Preti, M.; Rolfo, A.; Benedetto, C.; Revelli, A.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women Undergoing In-Vitro Fertilization: Effects on Embryo Development Kinetics and Live Birth Rate. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, M.; Sar-Shalom Nahshon, C.; Feferkorn, I.; Bornstein, J. Evaluation of Human Papilloma Virus in Semen as a Risk Factor for Low Sperm Quality and Poor in Vitro Fertilization Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fertil Steril 2020, 113, 955-969.e4. [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, M.; Söderlund-Strand, A.; Vänskä, S.; Luostarinen, T.; Eriksson, T.; Natunen, K.; Apter, D.; Baussano, I.; Harjula, K.; Hokkanen, M.; et al. Impact of Gender-Neutral or Girls-Only Vaccination against Human Papillomavirus—Results of a Community-Randomized Clinical Trial (I). Int J Cancer 2018, 142, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vänskä, S.; Luostarinen, T.; Baussano, I.; Apter, D.; Eriksson, T.; Natunen, K.; Nieminen, P.; Paavonen, J.; Pimenoff, V.N.; Pukkala, E.; et al. Vaccination with Moderate Coverage Eradicates Oncogenic Human Papillomaviruses If a Gender-Neutral Strategy Is Applied. J Infect Dis 2020, 222, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sanjose, S.; Bruni, L. Is It Now the Time to Plan for Global Gender-Neutral HPV Vaccination? Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 222, 888–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.L.; Kavanagh, K.; Pan, J.; Love, J.; Cuschieri, K.; Robertson, C.; Ahmed, S.; Palmer, T.; Pollock, K.G.J. Human Papillomavirus Prevalence and Herd Immunity after Introduction of Vaccination Program, Scotland, 2009–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Possible responses | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Level of education | No education 8 grade education 10 grade education High school degree/ Professional degree Bachelor’s degree or higher |

| 2 | Age | Numerical |

| 3 | Place of residence | Name of town/village |

| 4 | Have you ever been tested before by Pap smear? | YES NO |

| 5 | When have you been tested by Pap smear? | Free form answer |

| 6 | Would you have gone to be tested if the mobile screening unit wouldn’t have come to your town/village? | YES NO |

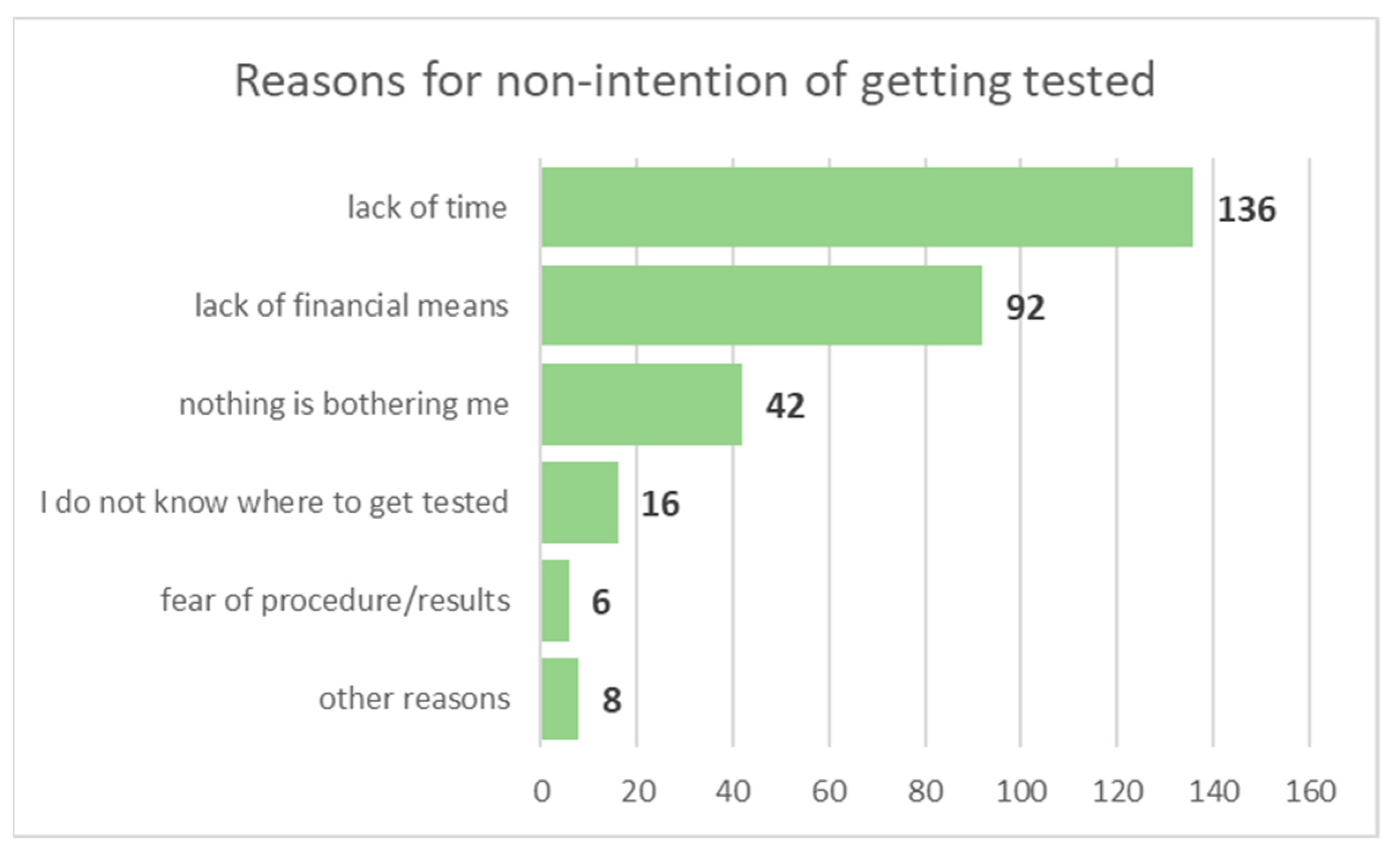

| 7 | If the answer to the previous question is NO then answer why not? | Lack of financial means Lack of time I do not know where to get tested Nothing is bothering me Other reasons |

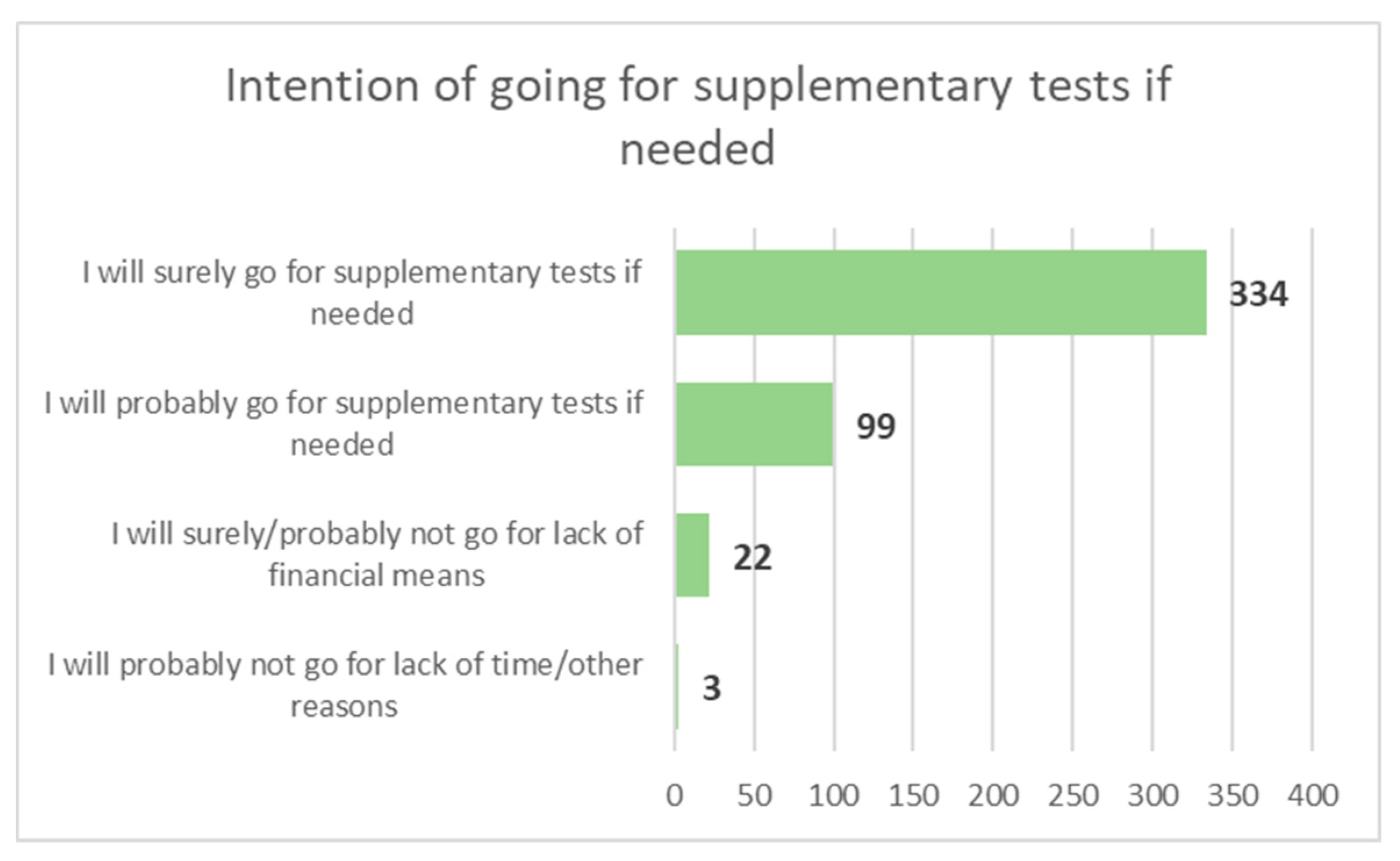

| 8 | If you will get a test result that requires other investigations, will you do them? | Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no due to the lack of financial means Probably no due to other reasons Definitely no |

| 9 | Have you ever heard that HPV infection can lead to cervical cancer? | YES NO |

| 10 | Do you know there is an HPV vaccine available? | YES NO |

| 11 | Are you HPV vaccinated? | YES NO |

| 12 | Are you aware that HPV vaccine is freely available for girls at the general practitioner? | YES NO |

| 13 | Knowing this would you vaccinate your daughters? | YES NO |

| 14 | If the answer to the previous question is NO then answer why not? | Free form answer |

| 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nr. of hospitalization episodes for CC | 3726 | 3028 | 2460 | 3775 | 4590 | 4679 | 4585 | 4315 | 5648 | 5734 | 4906 |

| Total nr. of hospitalization episodes | 12603 | 10962 | 11637 | 21008 | 21326 | 21153 | 22059 | 22393 | 22665 | 22029 | 21701 |

| Percentage | 29.56 | 27.62 | 21.14 | 17.97 | 21.52 | 22.12 | 20.79 | 19.27 | 24.92 | 26.03 | 22.61 |

| Nr. of unique patients treated for CC | 967 | 827 | 805 | 1290 | 1456 | 1543 | 1620 | 1585 | 1918 | 1994 | 1817 |

| Surgical procedures for CC | 668 | 651 | 642 | 1204 | 1251 | 1180 | 1274 | 1155 | 1911 | 1925 | 1868 |

| Total nr of surgical procedures | 4425 | 3947 | 3512 | 6338 | 6330 | 6392 | 6531 | 6611 | 6547 | 6612 | 6484 |

| Percentage | 15.09 | 16.49 | 18.28 | 18.99 | 19.28 | 18.46 | 19.5 | 17.47 | 29.18 | 29.11 | 28.8 |

| Percentage of ≥stage Ib CC | 92.15 | 94.61 | 87.32 | 89.14 | 91.57 | 90.86 | 91.79 | 89.99 | 93.63 | 92.47 | 91.52 |

| Medium hospital stay (days) | 7.62 | 10.12 | 10.25 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Medium cost of hospitalization episode for CC (Romanian Lei) | 12149 | 9833 | 5146 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).