1. Introduction

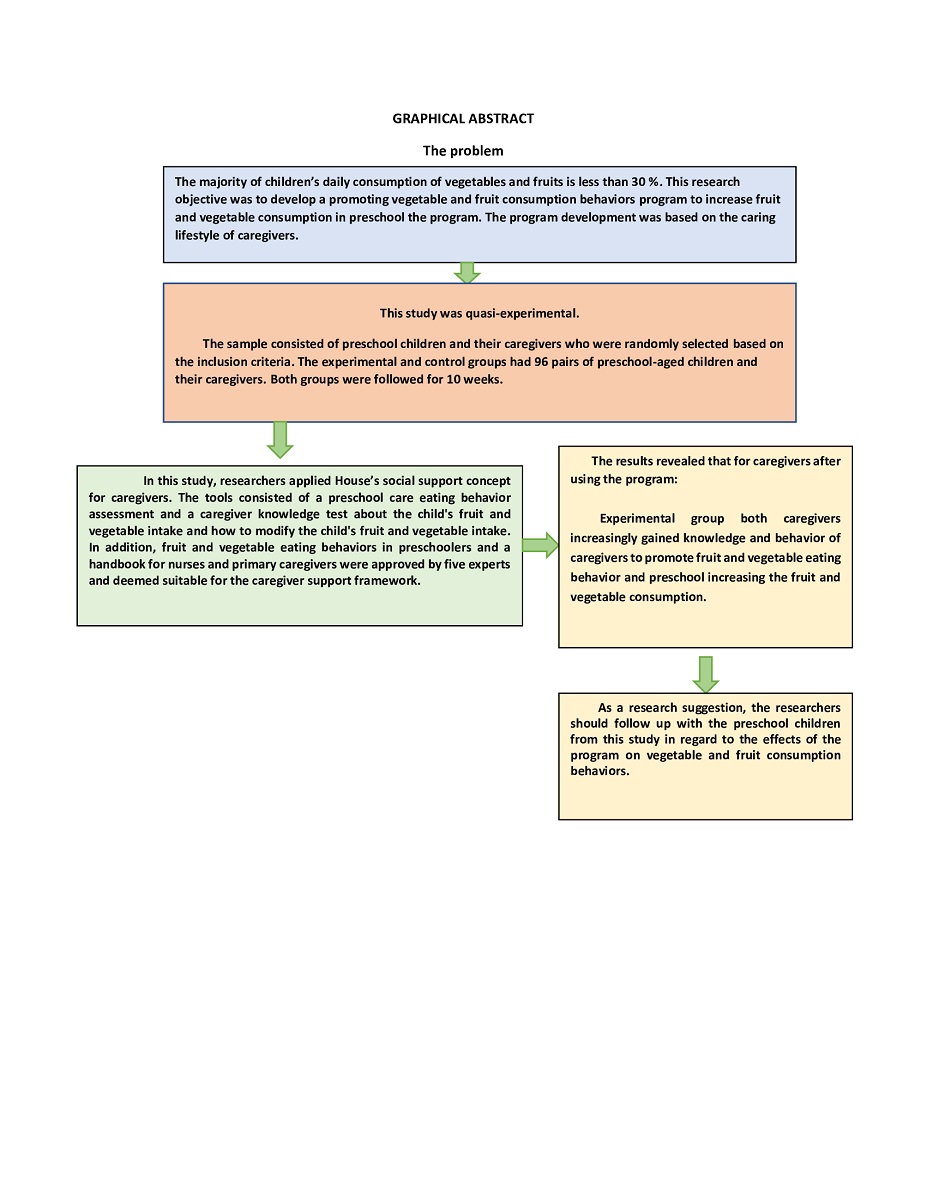

In every region of Thailand, the consumption of fruits and vegetables has decreased across all age groups and genders, particularly among children. The majority of children’s daily consumption of vegetables and fruits is less than 30 %. Children aged 2 - 5 years both males and females consume fewer vegetables than children aged 6 - 14 years [

1]. Only 6.5 % of children ages 2 to 5 consume the suggested amounts of fruits and vegetables. The fruit and vegetable consumption rate among younger children declines as they get older [

2]. The average daily consumption of fruits and vegetables among preschoolers is approximately 150 grams, which is significantly lower than the standard [

3]. According to a study of the eating habits of children at Aoluek School in Krabi, 60 % of the vegetables prepared for lunch are left over after lunchtime [

4].

The factors affecting the consumption behavior of vegetables and fruits in preschool children are caused by 2 factors: 1) environment and parental upbringing; preschool children imitate their parent’s eating habits or even the child’s own siblings [

5]. In addition to parents’ personal factors, generic family characteristics, such as household income, influence children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. It was discovered that children from high-income households consume a greater variety of fruits and vegetables than those from low-income households [

6]. Some preschoolers may have dietary restrictions or may be at an age where they are more interested in their environment than in food. If children are compelled to consume that type of food, they will be impressed and avoid it in the future. 2) A study of the factors influencing children’s eating behavior determined that children tend to make food selections, particularly regarding vegetables and fruits. Some fruits and vegetables can be quite bitter and sour when first tried, which can discourage children from eating them next time [

7,

8]. Vegetables’ odor and generally unappealing green color are also contributing factors in children’s aversion to them. When these issues increasingly arise, caregivers will naturally avoid preparing meals that involve vegetables.

According to the study, it is essential to care for preschools in order to improve children’s consumption of vegetables and fruits; the caregiver will be the one who nurtures and acts as a role model. Therefore, it is necessary to develop guidelines for giving advice and providing excellent emotional support and knowledge-based preschool care [

9]. The study of concepts and theories to support children eating fruits and vegetables revealed that the social support theory of House [

10] was comprehensive in creating reinforcements to be applied in program construction, particularly the building of support in caregivers because caregivers are an important support force to encourage children to eat nutritious food through the provision of information [

11]. In addition, to encourage the occurrence of physical actions related to preschool children, we must construct reinforcements both emotionally and instrumentally [

9].

Developing a program that includes four types of social support and evaluating feedback on consumption during the program are rarely to find. Moreover, most programs promote factors related to the appearance menu, and the color of bringing fruits and vegetables to adapt to different types of food menus, creating knowledge for early childhood children. [

4,

12] But there is no program that manages the environment to promote fruit and vegetable intake. The caregiver is a good example of eating fruits and vegetables or creating positive emotions for early childhood children to eat fruits and vegetables. In addition, it was found that the past use of social support theory was only a study of factors related to the intake of fruits and vegetables. [

9,

11] But only a small percentage of them adopted the theory of social support was used in the design for the development of a program to promote vegetable and fruit intake.

Currently, the situation of eating fruits and vegetables in preschool is on a downward trend. Based on an analysis of previous programs, it was determined that the population aged 1 - 3 years, school-aged children, and students were studied for the program to promote the consumption of vegetables and fruits. In the group of preschool children, factors associated with fruit and vegetable consumption were investigated, as well as strategies for promoting fruit and vegetable consumption in child development centers through education and menu modification. However, it does not promote family environment management or the development of primary caregivers at home. Therefore, the researcher develops a program and tool to assess the fruit and vegetable consumption habits of preschool-aged children living with their primary caregivers. This is due to the fact that the primary caregiver is an essential model for preschoolers to imitate [

13,

14,

15].

This study aimed to develop a program to promote fruit and vegetable consumption among preschool children and a tool to assess their fruit and vegetable consumption. And to compare the knowledge and behavior of caregivers to promote fruit and vegetable eating behavior between the control group and the experimental group, additionally to compare preschool eating behaviors of F&V consumption before-and-after intervention to promote F&V eating behaviors in preschool caregivers within the control, and experimental group.

2. Conceptual framework

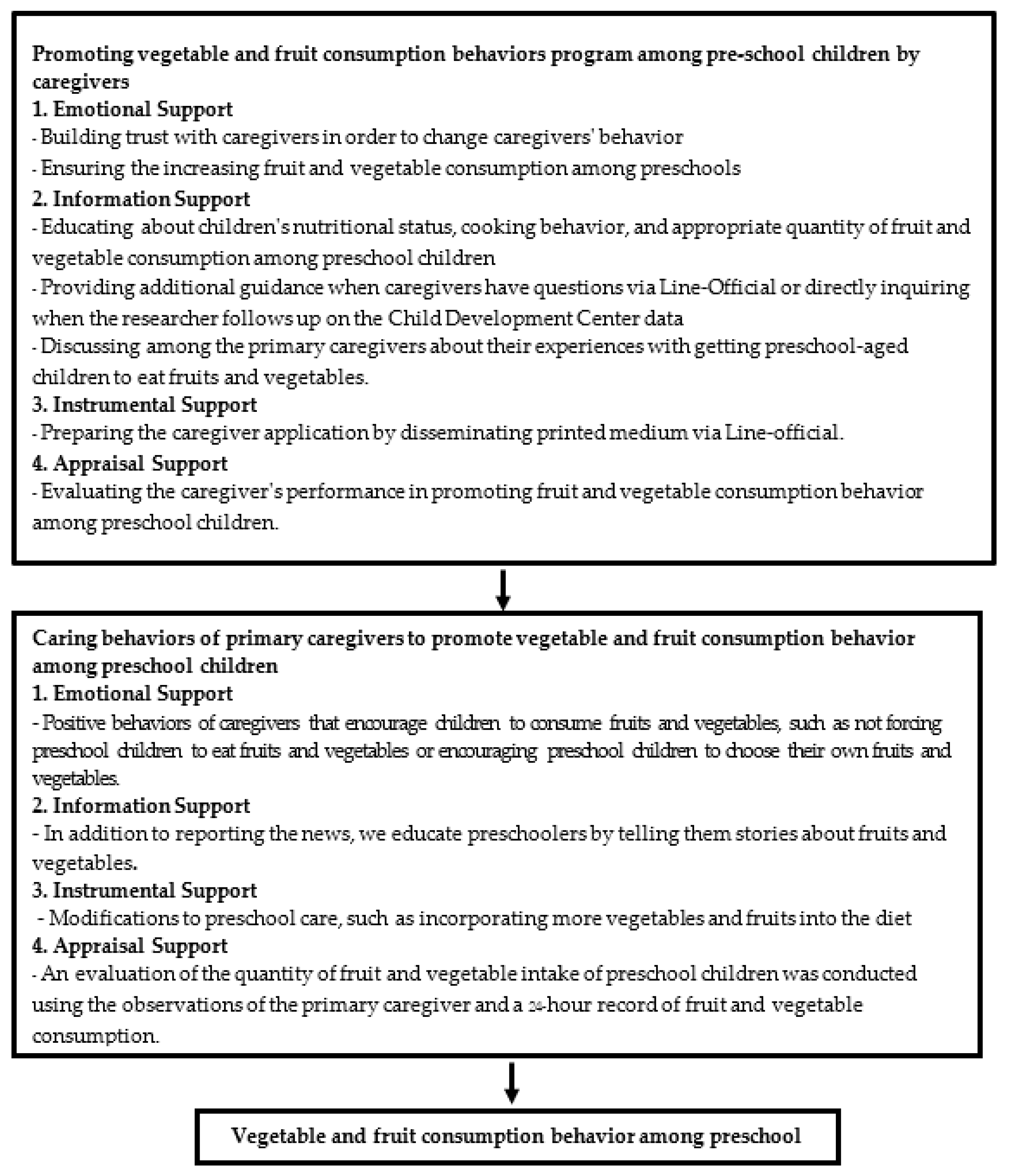

House’s concept of social support [

10] has been applied to the study of promoting fruit and vegetable intake in preschool children, and it has been discovered that parents play a crucial role in fostering social support for children to consume healthy food. Parents are responsible for establishing boundaries regarding the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Emotional support, including being a positive model in eating by parents, is statistically significantly associated with children’s fruit and vegetable eating behavior [

9], as is parental encouragement of fruit and vegetable consumption [

16].

To evaluate the effectiveness of a promoting fruit and vegetable consumption behavior program among preschool children of primary caregivers in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, the conceptual framework of social support is applied for 10 weeks. The literature review revealed that the caregiver is an important factor in introducing nutritious diets such as fruits and vegetables to children [

17], is a model of children’s consumption [

18], and is an important factor in creating an environment or reinforcing healthy eating [

2,

9,

18]. According to House’s conceptual framework of social support, social support can be divided into 4 categories:

Emotional Support - Acceptance, attention, and respectfulness on thoughts and behavior

Appraisal Support - Feedback and demonstrating value

Information Support - Providing knowledge and information as a guide for problem-solving

Instrumental Support - Demonstrating support through the use of equipment and appropriate items or services

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Measures

This study had a quasi-experimental research design conducted in two groups with a pre-test and post-test design. This research aims to develop programs and research instruments for primary caregivers to promote fruit and vegetable consumption among preschool children. According to the conceptual framework of House’s (1988) social support theory, 96 pairs of preschool-aged children and their primary caregivers in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province were used to test the instruments designed by the researchers.

The researchers selected a sample using random sampling as follows:

Purposive sampling; According to a random selection, a child development center in Muang District, Nakhon Si Thammarat was selected. In every household, the primary caregivers in the Muang District experience a similar urban lifestyle. There are 19 child development centers in Muang District, supervised by the sub-district administrative organization, Muang District, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province.

Simple random sampling; It is a sampling without replacement and must draw a name list of child development centers under the Sub-District Administrative Organization, Muang District, Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, with a total of 1 center.

Names of children from student records were used to select the sample based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

3.2. Research Instruments

The researcher developed the following research instruments:

1. The data collection instruments for this study were divided into 4 sections:

1.1.

Section 1 General information questionnaire consisted of a 3-part questionnaire:

Part 1: Personal information questionnaire of preschool children, namely sex, age, weight, and height

A weight-height chart for children aged 2 to 5 years was utilized to compare the age, weight, and height of preschoolers.

Part 2: The primary caregiver’s personal information questionnaire, namely, sex, age, relationship to preschool children, the greatest level of education, occupation, and monthly household income.

1.2.

Section 2: A questionnaire investigating the behavior of children taking care of family meals

It was adapted from the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) ([

14]) into a total of 20 questions, consisting of 14 positive questions and 6 negative questions, regarding the behaviors of primary caregivers in encouraging children to consume fruits and vegetables. The performance grading criteria were categorized into 5 levels as follows:

Table 1.

Grading of performance to encouraging children to consume fruits and vegetables in a week.

Table 1.

Grading of performance to encouraging children to consume fruits and vegetables in a week.

| Option details |

Positive

(Score) |

Negative

(Score) |

| Every day |

5 |

1 |

| 5 - 6 times per week |

4 |

2 |

| 3 - 4 times per week |

3 |

3 |

| 1 - 2 times per week |

2 |

4 |

| Never |

1 |

5 |

1.3.

Section 3: An evaluation of caregivers’ knowledge of their children’s fruit and vegetable consumption and how to encourage their child’s fruit and vegetable eating behavior. It consisted of 4 multiple-choice questions, totaling 8 items, with the following criteria for scoring:

If the caregiver gave a correct answer, the score was given 1

If the caregiver gave a wrong answer, the score was given 0

1.4.

Section 4 24-hour consumption of fruits and vegetables among preschool children

It was modified from the 24-hour eating behavior record form, and it required the primary caregiver to record the children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables over the previous 3 days.

The caregiver estimated the proportion of vegetables consumed at each meal using a tablespoon to measure and record the results. The researcher then calculated the quantity recorded by the primary caregiver, using the unit as a portion.

The caregiver estimated the proportion of fruits consumed at each meal by counting the number of fruits or pieces of fruit to measure and record the results. The researcher then calculated the quantity recorded by the primary caregiver, using the unit as a portion.

2. Experimental instruments

A promoting fruit and vegetable consumption behavior program among preschool children employed the social support theory proposed by House (1988) as a framework. The experimental period was 10 weeks, and the instruments used to implement the program were as follows:

2.1. A handbook for nurses consisted of the implementation of a 10-week program to promote fruit and vegetable eating behavior in preschool children, steps and activities to support the primary caregivers of preschool children, and a follow-up of fruit and vegetable eating behavior in preschool children.

2.2. A handbook for primary caregivers was published online via the LINE application to encourage preschool children to consume more fruits and vegetables.

3.3. Data Collection

The duration of the intervention was 10 weeks. The control group in 1st week collected pre-test data. 2nd – 10th week follow the assessment of 24-hour recording of preschool eating habits of fruits and vegetables recorded every 3 wks. 10th week collected post-test data and gave the E-book to the caregiver and advice to improve eating F&V of preschool. The difference between the control and experiment groups is that in the 2nd– 10th week the researcher gave the information via Line official and a person’s advice to the caregiver and the caregiver group shared their experience about how to promote fruit and vegetable consumption in preschool by using social support framework.

3.4. Ethical statement

All procedures involving human participants that were performed in the studies followed the ethical standards of the Ethical Institutional Consideration. This research was considered for approval by the Ethics Committee in Human Research Walailak University, certificate number WUEC-22-110-01, certified as of April 4, 2022. The researchers conducted the study following the Declaration of Helsinki. The researchers contacted the participants about the study’s purpose, significance, and procedure and explained voluntary participation and the unaffected withdrawal principle. Before starting, the caregivers signed written informed consent. All procedures involving human participants that were performed in the studies followed the ethical standards of the Ethical Institutional Consideration. Participants’ data were only used for academic purposes and will not be disclosed to anyone other than the relevant researchers.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistics were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0.0.1. Statistics used in the data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, comparing the differences in general information among the experimental group and control group using the Chi-square, Fisher’s exact test, and independent t-test statistics. The differences in mean scores comparing the data on the feeding behavior of caregivers and knowledge about methods for modification in preschool’s behaviors in eating fruits and vegetables between the control and experimental group were analyzed using the t-test. The differences in mean scores suggesting compare preschool eating behaviors of F&V consumption before-and-after intervention within the control and experimental group using t-test statistics.

4. Results

For the characteristics of the preschool children, it was found that 55.21% of the children in the sample group were male and 44.79% were female. Overall, children’s growth was in the normal range, with 51.04% meeting the weight-for-length criteria. When comparing the differences in the preschool children’s general information between the control group and experimental group, it was found that there was no statistically significant difference (

p > 0.05), as shown in

Table 2.

The caregivers’ characteristics consisted of 96 subjects included 79.2% were female. The average age was 37.5 years (S.D. = 11.48), with 77.1% parents and 16.7% grandparents. When comparing the differences in the general data of caregivers between the control group and the experimental group, it was found that there was no statistically significant difference (

p > 0.05), as shown in

Table 3.

A comparison was performed on the difference in mean scores of caring behaviors of the main caregivers to encourage preschool to eat fruits and vegetables before participating in the program between the experimental group and the control group. There was no statistically significant difference (

p > 0.05), as shown in

Table 4.

The mean scores of caring behaviors of the main caregivers to encourage preschool to eat fruits and vegetables after participating in the program (M = 79.52, SD = 4.40) were higher than before participating in the program (M = 72.67, SD = 7.72). It was found that there were statistically significant (p < 0.001). The experimental group (M = 79.52, SD = 4.40) had a higher mean knowledge score than the control group (M = 71.06, SD = 6.97) the mean knowledge score of caregivers. main for early childhood children to eat fruits and vegetables in the experimental group (M = 5.92, SD = 1.4) was higher than the control group (M = 4.33, SD = 1.53), found that it was statistically significant (p < 0.001)

, as shown in

Table 5.

3. Behavior score, it was found that the average score of vegetable and fruit eating behaviors of preschool children in the experimental group (M = 3.42, SD = 2.00) increased compared to before joining the program (M = 2.52, SD = 2.04) and the mean score of eating behavior the fruit of early childhood children in the experimental group (M = 4.17, SD = 3.83) increased compared to before they were enrolled in the program (M = 5.61, SD = 3.1). The fruit-eating behavior score of preschool children in the experimental group (M = 3.42, SD = 3.38) was higher than that of the control group (M = 1.81, SD = 2.07). SD = 3.1) higher than the control group (M = 2.98, SD = 2.65), found that there was a statistically significant difference (p < 0.01) ), as shown in Table 6.

5. Discussion

After receiving a program to promote vegetable and fruit consumption behaviors among preschool children, it was found that in the experimental group, when comparing before and after behaviors of taking care of preschool children eating food by caregivers, knowledge of the caregiver about the child’s fruit and vegetable intake and how to modify the child’s fruit and vegetable eating behaviors in preschool children. The consumption of vegetables and fruits among preschool children tends to be higher than before the experiment. The results indicate that receiving the program, along with social support in all 4 aspects (emotional support, information support, instrumental support, and appraisal support), can be discussed as follows:

Through emotional support throughout the entire operation, the researchers assured that caregivers were able to encourage preschoolers’ fruit and vegetable consumption in an upward direction, thereby opening inquiry channels to reduce stress during practices [

19]. When caregivers reduced stress and pressure, children consumed more fruits and vegetables and felt happier during meals [

20]. In addition, the sharing of ideas and encouragement among caregiver groups was essential to bolstering caregivers’ confidence in carrying out appropriate fruit and vegetable consumption guidelines for children.

For information support, educating about children’s nutritional status, caring behavior to encourage children to eat their meals, the appropriate amount of fruit and vegetable consumption among preschool children, the impact of not consuming vegetables and fruits, and how to make food look appetizing – all of these will provide primary caregivers with appropriate guidance in meal planning for children [

21]. Improve food’s visual appeal [

22] and guidelines for teaching children to eat correctly and properly [

23].

For instrumental support in preparing the caregiver application, it was determined that creating materials with knowledge-based content and additional inquiry channels will help caregivers gain confidence. They can ask questions to get additional information about how to encourage children to eat more fruits and vegetables, such as by making food more visually appealing.

Appraisal support was conducted by monitoring the consumption behavior of preschool children and providing the primary caregiver with feedback for promoting an appropriate caregiving style and an additional style.

The House [

10] social support theory was adopted so that primary caregivers could receive adequate and comprehensive social support. The preschool children care guidelines provided to primary caregivers included social support in all four aspects, namely emotional support, informational support, instrumental support, and appraisal support, which parents could apply according to the context of each family in order to encourage preschool children to eat fruits and vegetables.

The limitation of this study, the sample size of 96 participants might represent a community in Nakhon Si Thammarat but not a whole country. In addition, the number of preschool children samples included more boys than girls in each group before participating in the program but with no statistically significant difference.

6. Conclusions

The program to promote vegetable and fruit consumption behaviors among preschool children was to develop caregivers in terms of knowledge and behaviors, it was found that in the experimental group when comparing before and after behaviors of taking care of preschool children eating food by caregivers, knowledge of the caregiver about the child’s fruit and vegetable intake and how to modify the child’s fruit and vegetable eating behaviors in preschool children. As a research suggestion, the researchers should follow up with the preschool children from this study in regard to the effects of the program on vegetable and fruit consumption behaviors.

Author Contributions

S.W. designed the methodology, executed the study in this research, data collection, and analyses, and wrote the original draft in the manuscript. T.E. and K.K. assisted with designing the study, executing the study, data analyses, supervising, and writing and editing the draft and final manuscript. R.J. assisted with the data analyses. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported and awarded to the first author by a grant from the Research Institute for Health Sciences and the Excellence Center of Nursing Institute, Walailak University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Walailak University (protocol code WUEC-22-110-01 and date of approval 4th April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be provided by request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wambogo, E.A.; Ansai, N.; Ahluwalia, N.; Ogden, C.L. Fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents in the United States, 2015-2 018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020, 391, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Steeves, E.A.; Jones-Smith, J.; Hopkins, L.; Gittelsohn, J. Perceived social support from friends and parents for eating behavior and diet quality among low-income, urban, minority youth. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aekplakorn, W. Thai child national health examination survey; NHES V: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eksirinimit, T.; Somlak, K.; Kusol, K.; Rithipukdee, N.; Kaewpawong, P. Health behavior promotion model vegetables and fruit consumption of students Aow Luek School, Krabi Province. Princess Naradhiwas Univ. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 8, 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics 1998, 101, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, S.; Renker-Darby, A.; Harré, S.; Rees, D.; Raroa, D.A.; Eickstaedt, M. , Sushil, Z.; Allan, K.; Bartos, A.E.; Waterlander, W.E.; Swinburn, B. Improving low fruit and vegetable intake in children: Findings from a system dynamics, community group model building study. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0221107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmett, P.M.; Hays, N.P.; Taylor, C.M. Antecedents of picky eating behavior in young children. Appetite 2018, 130, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.; Albuquerque, G.; Silva, C.; Oliveira, A. Appetite-related eating behaviors: An overview of assessment methods, determinants and effects on children’s weight. Ann. Nutr. Metabol. 2018, 73, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heredia, N.I.; Ranjit, N.; Warren, J.L.; Evans, A.E. Association of parental social support with energy balance-related behaviors in low-income and ethnically diverse children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Publ. Health. 2016, 16, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, J.S.; Umberson, D.; Landis, K.R. Structures and processes of social support. Ann. Rev. Social. 1988, 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeves, E.A.; Jones-Smith, J.; Hopkins, L.; Gittelsohn, J. Perceived social support from friends and parents for eating behavior and diet quality among low-income, urban, minority youth. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, A. L. , Himberg-Sundet, A., Bjelland, M., Lien, N., Holst, R., & Andersen, L. F. Exploring intervention components in association with changes in preschool children’s vegetable intake: The BRA-study. BMC Research Notes. 2021, 14, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.E.; Deng, Y.M. The role of caregiver’s feeding pattern in the association between parents and children’s healthy eating behavior: Study in Taichung, Taiwan. Children 2021, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J. , Guthrie, C. A., Sanderson, S., & Rapoport, L. Development of the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2001, 42, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Shang, L. Caregivers’ feeding behavior, children’s eating behavior and weight status among children of preschool age in China. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raising Children Network. Vegetables: tips to encourage your child to eat more. Available online: https://raisingchildren.net.au (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Schoeppe, S.; Trost, S.G. Maternal and paternal support for physical activity and healthy eating in preschool children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015, 15, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, M.; Palmeir, A.; Gaspar, T.; Wit, J.; Luszczynska, A. Social support influences on eating awareness in children and adolescents: The mediating effect of self-regulatory strategies. Global Public Health. 2015, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.C.; Daundasekara, S.S.; Arlinghaus, K.R.; Sharma, A.P.; Reitzel, L.R.; Kendzor, D.E.; Businelle, M.S. Fruit and vegetable consumption and emotional distress tolerance as potential links between food insecurity and poor physical and mental health among homeless adults. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 14, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.; Blissett, J.; Brunstrom, J.; Carnell, S.; Faith, M.; Fisher, J.; Hayman, L.L.; Khalsa, A.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Miller, A.L.; Momin, S.R.; Welsh, J.A.; Woo, J.G.; Haycraft, E. Caregiver influence on eating behaviors in young children: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motebejana, T.T.; Nesamvuni, C.N.; Mbhenyane, X. Nutrition knowledge of caregivers influences feeding practices and nutritional status of children 2 to 5 years old in Sekhukhune District, South Africa. Ethiopian J. Health Sci. 2022, 32, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, V. , Graaf, C., & Jager, G. Use of different vegetable products to increase preschool-aged children’s preference for and intake of a target vegetable: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2017, 117, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeneke, R.U.; Nwajiuba, C.A.; Igberi, C.O.; Amadi, M.U.; Anosike, F.C.; Oko-Isu, A.; Munonye, J.; Uwadoka, C.; Adeolu, A.I. Impacts of caregivers’ nutrition knowledge and food market accessibility on preschool children’s dietary diversity in remote communities in Southeast Nigeria. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).