Submitted:

27 July 2023

Posted:

31 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

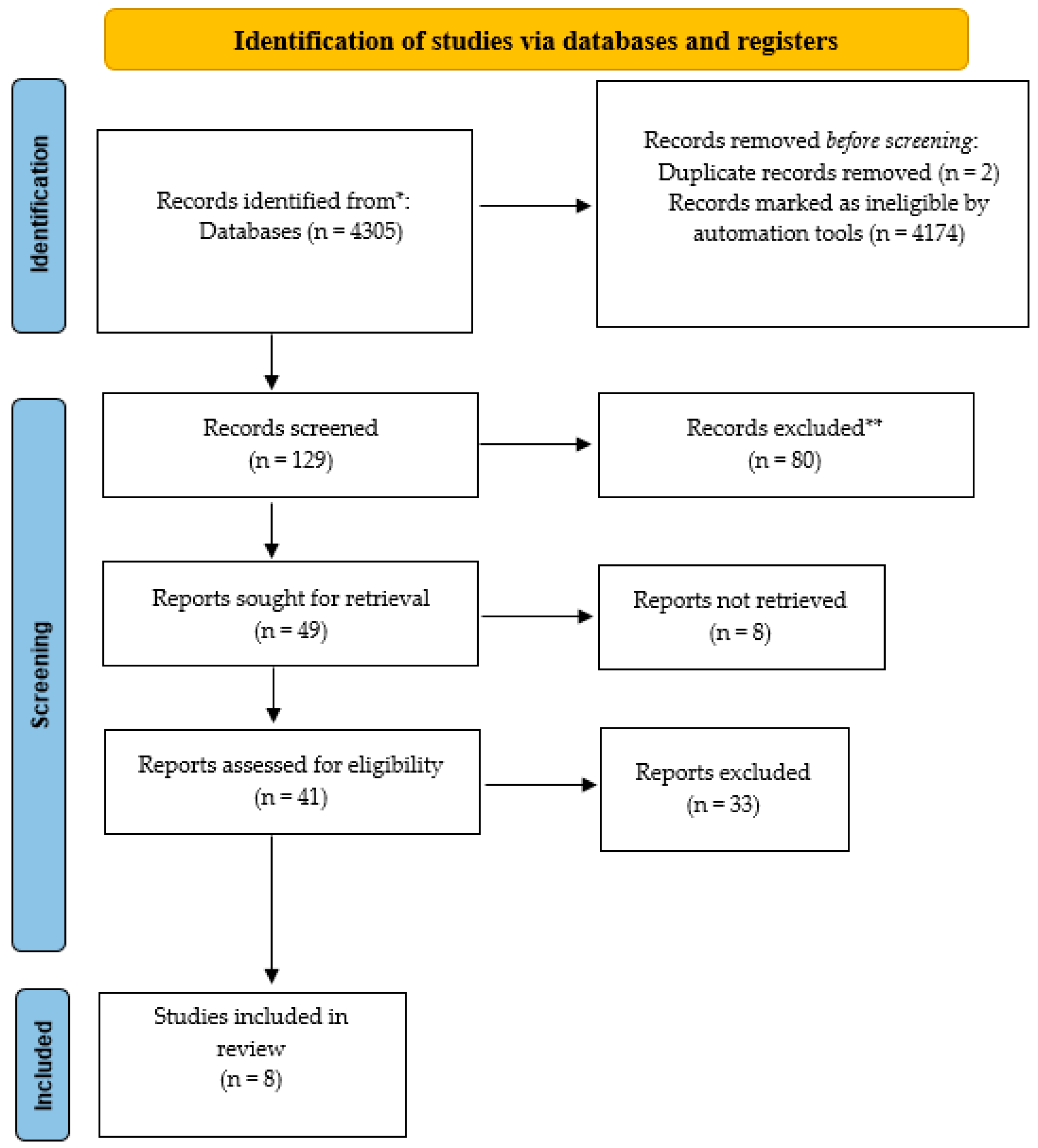

2.1. Serarch Strategy and Study Selection

- culture of safety within healthcare facilities;

- event reporting through incident reporting;

- culture of safety and reporting of adverse events.

2.2. Data collection, extraction, synthesis and quality assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Patient safety in developing and transitional countries: new insights from Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2011.

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.M.; Donaldson, M.S. Errors in Health Care: A Leading Cause of Death and Injury. In: To Err Is Human: Building a Sager Health System, National Academy Press, Washington DC, 2000, 26-48.

- Mira, J.J.; Cho, M.; Montserrat, D.; Rodríguez, J.; Santacruz, J. Elementos clave en la implantación de siste- mas de notificación de eventos adversos hospitalarios en América Latina. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013, 33(1), 1–7.

- Royal College of Physicians. National Audit of Inpatients Falls: Audit report 2017. London, Royal College of Phsysicians, 2017.

- Stainsby D. ABO incompatible transfusions--experience from the UK Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) scheme Transfusions ABO incompatible. Transfus Clin Biol. 2005, 12(5), 385-8. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Patient safety: making health care safer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization 2017.

- WHO. Patient Safety – Making Health Care Safe. Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2019.

- Leape, L. L.; Lawthers, A. G.; Brennan, T. A.; Johnson, W. G. Preventing medical injury. QRB. Quality review bulletin, 1993, 19(5), 144–149. [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Rose, N.; Germann, D. Resultate eines krankenhausweiten Critical Incident Reporting System (CIRS). Gesundheitsökonomie Qualitätsmanagement. 2005,10(2), 83–9. [CrossRef]

- Tereanu, C.; Minca, D.G.; Costea, R; Grego, S; Ravera, L; Pezzano, D.; Vigano, P. ExpIR-RO: a collaborative international project for experimenting voluntary incident reporting in the public healthcare sector in Romania. Iran J Public Health. 2011, 40(1), 22–31.

- Nakajima, K.; Kurata, Y.; Takeda, H. A web-based incident reporting system and multidisciplinary collaborative projects for patient safety in a Japanese hospital. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005, 14(2), 123–9. [CrossRef]

- World Alliance for Patient Safety. WHO draft guidelines for adverse event reporting and learning systems. 2005. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69797/WHO-EIP-SPO-QPS-05.3-eng.pdf (accessed on July 7, 2023).

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Optimizing Graduate Medical Trainee (Resident) Hours and Work Schedule to Improve Patient Safety. In: Ulmer C, Miller Wolman D, Johns MME, editors. Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2009. p. 8. System Strategies to Improve Patient Safety and Error Prevention. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK214937/ (accessed on July 7, 2023).

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Politica Social de Espana/OMS. Estudio IBEAS: Prevalencia de efectos adversos en hospitales de Latinoamerica, 2019.

- Parra, C.V.; Lopez, J.S.; Bejarano, C.H.; Puerto, A.H.; Galeano, M.L. Eventos adversos en un hospital pediatrico de tercer nivel de Bogota. Rev Fac Nac Salud Publica. 2017, Vol. 35, N.2.

- Mira JJ, Carrillo I, Lorenzo S, Ferrús L, Silvestre C, Pérez-Pérez P, Olivera G, Iglesias F, Zavala E, Maderuelo-Fernández JÁ, Vitaller J, Nuño-Solinís R, Astier P; Research Group on Second and Third Victims. The aftermath of adverse events in Spanish primary care and hospital health professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015, 9(15), 151. [CrossRef]

- Khon, L.; Corrigan, J.; Donaldson, M. Errare è umano: costruire un sistema sanitario più sicuro. Comitato per la qualità della salute in America, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999.

- Miasso, A.; Grou, C.; Cassiani, S.; Silva, A.; Fakih, F. Erros de medicacno: Tipos, fatores causais e providencias em quatro hospitais brasileiros. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2006, 40(4).

- Del Vecchio, M.; Cosmi, L. Il Risk management nelle aziende sanitarie. Milano, McGraw-Hill, 2003.

- Damiani, G.; Specchia, M.; Ricciardi, W. Manuale di Programmazione e organizzazione sanitaria. Napoli, Idelson-Gnocchi, 2018.

- Secretary of State for Health. The New NHS: modern, dependable. London, Stationery Office, 1997.

- Ricciardi, W.; Boccia, S. Igiene, Medicina Preventiva e Sanità Pubblica. Napoli: Idelson-Gnocchi, 2021.

- Buscemi, A.; Limone, D.; Bugiolacchi, L.; Turco, A. Il Risk management in sanità (2nd ed.). Milano: Franco Angeli, 2015.

- Bizzarri, G.; Canciani, M.; Farina, M. Strategia e gestione del rischio clinico nelle organizzazioni sanitarie: approcci, modalità, strumenti e risultati. Milano, Franco Angeli, 2018.

- Cascini, F., La Regina, M., Ricciardi, W., & Tartaglia, R. Manuale di sicurezza del paziente e gestione del rischio clinico. Perugia, Cultura e Salute Editore, 2022.

- Joint Commission International. JCI Accreditation Standards for Hospitals, 7th ed.; Joint Commission Resources: Oakbrook Terrace, IL, USA, 2020.

- Vetrugno, G.; Foti, F.; Grassi, V.M.; De-Giorgio, F.; Cambieri, A.; Ghisellini, R.; Clemente, F.; Marchese, L.; Sabatelli, G.; Delogu, G.; et al. Malpractice Claims and Incident Reporting: Two Faces of the Same Coin? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16253. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [CrossRef]

- Ma, LL.; Wang, YY.; Yang, ZH. et al. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: what are they and which is better?. Military Med Res 2020, 7, 7. [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati, M. H.; Short, S. D.; Abdulhadi, N. N.; Panchatcharam, S. M.; Dennis, S. Assessment of patient safety culture in primary health care in Muscat, Oman: A questionnaire -based survey. BMC Family Practice, 2019, 20(1), 50. [CrossRef]

- Carlfjord, S.; Öhrn, A.; Gunnarsson, A. Experiences from ten years of incident reporting in health care: A qualitative study among department managers and coordinators. BMC Health Services Research, 2018, 18(1), 113. [CrossRef]

- De Kam, D.; Kok, J.; Grit, K.; Leistikow, I.; Vlemminx, M.; Bal, R. How incident reporting systems can stimulate social and participative learning: A mixed-methods study. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2020, 124(8), 834–841. [CrossRef]

- Flott, K.; Nelson, D.; Moorcroft, T.; Mayer, E. K.; Gage, W.; Redhead, J.; Darzi, A. W. Enhancing Safety Culture Through Improved Incident Reporting: A Case Study in Translational Research. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 2018, 37(11), 1797–1804. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Babamiri, M.; Pashootan, Z. A comprehensive method for the quantification of medication error probability based on fuzzy SLIM. PloS One, 2022, 17(2), e0264303. [CrossRef]

- Petschnig, W.; Haslinger-Baumann, E. Critical Incident Reporting System (CIRS): A fundamental component of risk management in health care systems to enhance patient safety. Safety in Health, 2017, 3(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Raeissi, P.; Reisi, N.; Nasiripour, A. A. Assessment of Patient Safety Culture in Iranian Academic Hospitals: Strengths and Weaknesses. Journal of Patient Safety, 2018, 14(4), 213–226. [CrossRef]

- Verbeek-van Noord, I.; Smits, M.; Zwijnenberg, N. C.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Wagner, C. A nation-wide transition in patient safety culture: A multilevel analysis on two cross-sectional surveys. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 2019, 31(8), 627–632. [CrossRef]

- Aaron, M.; Webb, A.; Luhanga, U. A Narrative Review of Strategies to Increase Patient Safety Event Reporting by Residents. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 2020, 12(4), 415–424. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-Y.; Lee, H.-F.; Lin, S.-Y.; Ma, S.-C. Factors contributing to voluntariness of incident reporting among hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 2019, 27(4), 806–814. [CrossRef]

- Commission J. Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in health care facilities. Sentinel Event Alert 2015, 55, 1-5.

- Ministero della Salute. Protocollo di monitoraggio degli eventi sentinella: 5° rapporto Settembre 2005-Dicembre 2012. Roma, 2013.

- Stainsby, D. ABO incompatible transfusions—experience from the UK Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) scheme Transfusions ABO incompatible. Transfusion clinique et biologique 2005, 12, 385–388. [CrossRef]

- Serious Hazards of Transfusion. Available from www.shotuk.org. (Accessed on July 23, 2023).

- Keogh, S.; Flynn, J.; Marsh, N.; et al. Varied flushing frequency and volume to prevent peripheral intravenous catheter failure: a pilot, factorial randomised controlled trial in adult medical-surgical hospital patients. Trials 2016, 17, 348. [CrossRef]

- Hadaway L. Short peripheral intravenous catheters and infections. J Infus Nurs 2012, 35, 230–40. [CrossRef]

- Guenezan, J.; Drugeon, B.; O'Neill, R. et al. Skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine–alcohol versus povidone iodine–alcohol, combined or not with use of a bundle of new devices, for prevention of short-term peripheral venous catheter- related infectious complications and catheter failure: an open- label, single-centre, randomised, four-parallel group, two-by-two factorial trial: CLEAN 3 protocol study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028549. [CrossRef]

- Makary, M.A.; Daniel, M. Medical error: The third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016, 353, i2139. [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.F.; Shackelford, S.A.; Tisherman, S.A.; Yang, S.; Puche, A.; Elster, E.A.; Bowyer, M.W. Retention and Assessment of Surgical Performance Group of Investigators. Critical errors in infrequently performed trauma procedures after training. Surgery. 2019, 166(5), 835-843. [CrossRef]

- Hartel, M.J.; Staub, L.P.; Röder, C.; Eggli, S. High incidence of medication documentation errors in a Swiss university hospital due to the handwritten prescription process. BMC Health Serv Res 2011, 11, 199. [CrossRef]

- Jolivot, P-A.; Pichereau, C.; Hindlet, P.; Hejblum, G.; Bigé, N.; Maury, E. et al. An observational study of adult admissions to a medical ICU due to adverse drug events. Ann Intensive Care 2016, 6(1), 9. [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Sakuma, M.; Matsui, K.; Kuramoto, N.; Toshiro, J.; Murakami, J.; Fukui, T.; Saito, M.; Hiraide ,A.; Bates, D.W. Incidence of Adverse Drug Events and Medication Errors in Japan: the JADE Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010, 26(2), 148–153. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Reporting and learning systems for medication errors: the role of pharmacovigilance centres. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/emp_mes/en (Accessed on July 12, 2023).

- Goedecke, T.; Ord, K.; Newbould, V. et al. Medication Errors: New EU Good Practice Guide on Risk Minimisation and Error Prevention. Drug Saf 2016, 39, 491–500. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2017b). WHO launches global effort to halve medication-related errors in 5 years. Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/29-03-2017-who-launches-global-effort-to-halve-medication-related-errors-in-5-years (Accessed on July 12, 2023).

- Suclupe, S.; Martinez-Zapata, M.J.; Mancebo, J. et al. Medication errors in prescription and administration in critically ill patients. JAN Loading Global Nursing Research 2020, 76(5), 1192-1200. [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.F.; Shackelford, S.A.; Tisherman, S.A.; Yang, S.; Puche, A.; Elster, E.A.; Bowyer, M.W. Retention and Assessment of Surgical Performance Group of Investigators. Critical errors in infrequently performed trauma procedures after training. Surgery. 2019, 166(5), 835-843. [CrossRef]

- Leape, L.L.; Brennan, T.A.; Laird, N.; et al. The nature of adverse events in hospi- talized patients: Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991, 324, 377e384. [CrossRef]

- Ausserhofer,D.; Zaboli, A.; Pfeifer, N.; Solazzo, P.; Magnarelli, G.; Marsoner, T.; Siller, M.; Turcato, G. Errors in nurse-led triage: An observational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2021, 113, 103788. [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.; Finch, C.; Coventon, L.; Salmon, P.M. Incidents in the Great Outdoors: A systems approach to understanding and preventing led outdoor accidents. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 2020, 64(1), 1740–1744. [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.; Williamson, A.; Lenné, M.; Mitsopoulos-Rubens, E.; Rudin-Brown, C. M.Systems-based accident analysis in the led outdoor activity domain: application and evaluation of a risk management framework. 2010, 53(8), 927-939. [CrossRef]

- Carden, T.; Goode, N.; Salomon P.M. Simplifying safety standard: Using work domain analysis to guide regulatory restructure. Safety Science 2021, 138, 105096. [CrossRef]

- Carden, T.; Goode, N.; Read, G.J.M.; Salmon, P.M. Sociotechnical systems as a framework for regulatory system design and evaluation: Using Work Domain Analysis to examine a new regulatory system. [CrossRef]

- Carden, T.; Goode, N.; Salomon, P.M. Not as simply as it look: led outdoor activities are complex sociotechnical systems. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 2017, 18(4), 318-337. [CrossRef]

- Dallat, C.; Salomon, P.M.; Goode, N. All about the Teacher, the Rain and the Backpack: The Lack of a Systems Approach to Risk Assessment in School Outdoor Education Programs. Procedia Manufacturing 2015, 3, 1157-1164. [CrossRef]

- McLean, E.V.; Whang, T. Do sanctions spell disaster? Economic sanctions, political institutions, and technological safety. European Journal of International Relations 2020, 26(3), 767-792. [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.; Coventon, L.; Finch, C.F.; Dallat, C.; Carden, T.; Salmon, P.M. Evaluation of a systems ergonomics-based incident reporting system. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 100, 103651.

- Goode, N.; Salmon, P.M.; Lenne, M.; Finch, C. Translating Systems Thinking into Practice. A Guide to Developing Incident Reporting Systems. CRC Press 2018, 26, 308.

- Jacobsson, A.; Ek, A.; Akselsson, R. Method for evaluating learning from incidents using the idea of “level of learning”. Journal of Loss Prevention in Process Industries 2011, 24(4), 333-343. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Carstensen, O.; Rasmussen, K. The prevention of occupational injuries in two industrial plants using an incident reporting scheme. Journal of Safety Research 2006, 37(5), 479-486. [CrossRef]

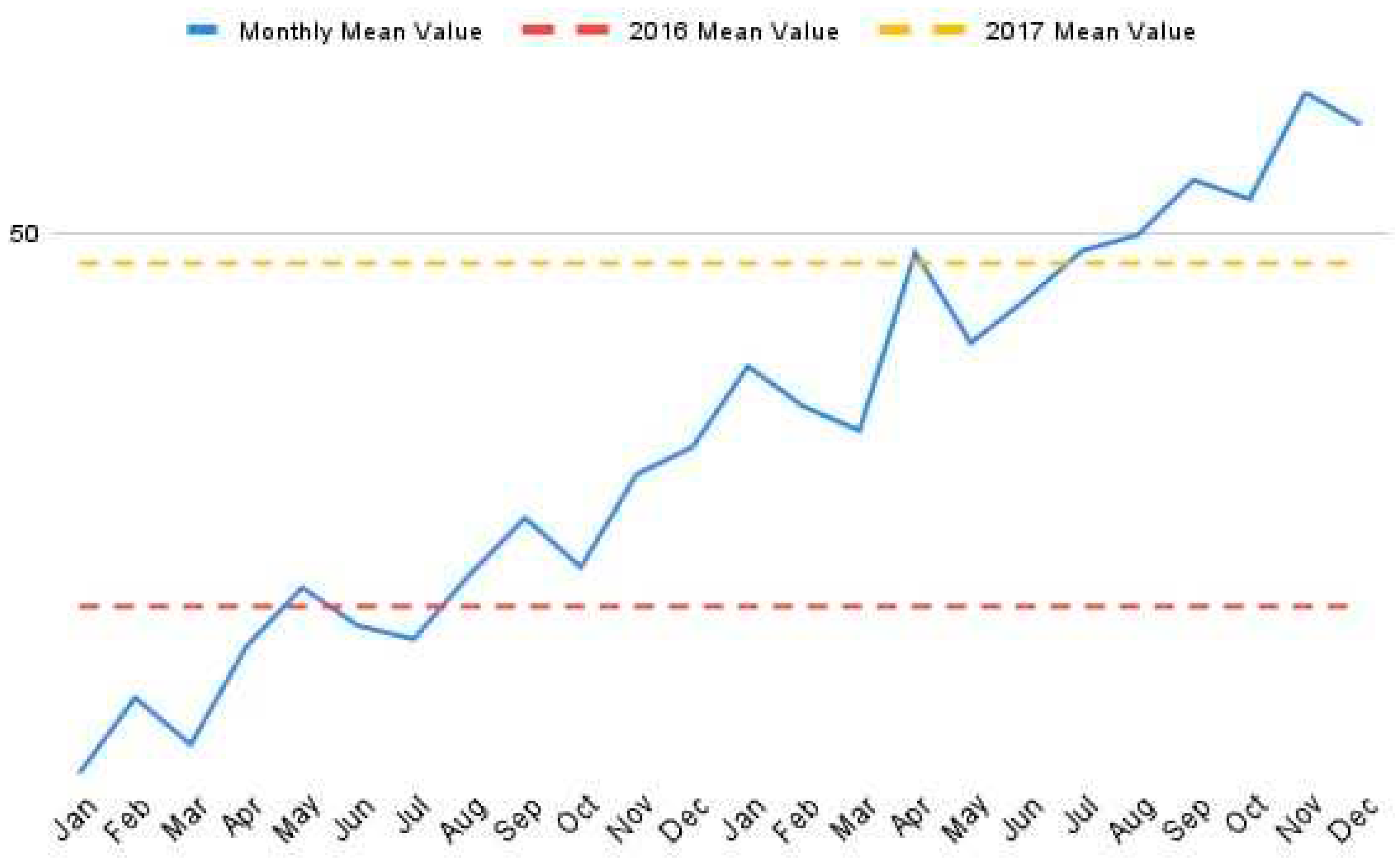

- Hutchinson, A.; Young, T. A.; Cooper, K. L.; McIntosh, A.; Karnon, J. D.; Scobie, S.; Thomson, R. G. Trends in healthcare incident reporting and relationship to safety and quality data in acute hospitals: Results from the National Reporting and Learning System. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2009, 18(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Ferorelli, D.; Solarino, B.; Trotta, S.; Mandarelli, G.; Tattoli, L.; Stefanizzi, P.; Bianchi, F. P.; Tafuri, S.; Zotti, F.; Dell’Erba, A. Incident Reporting System in an Italian University Hospital: A New Tool for Improving Patient Safety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,2020, 17(17). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Tian, L.; Yan, C.; Li, Y.; Fang, H.; Peihang, S.; Li, P.; Jia, H.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, S.; Anastasia, G.; Jiao, M.; Wu, Q.; Liu, M. A cross-sectional survey on patient safety culture in secondary hospitals of Northeast China. PloS One, 2019, 14(3), e0213055. [CrossRef]

- Plsek, P. E.; Wilson, T. Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations. BMJ, 2001, 323(7315), 746–749. [CrossRef]

- Yalew, Z. M.; Yitayew, Y. A. Clinical incident reporting behaviors and associated factors among health professionals in Dessie comprehensive specialized hospital, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: A mixed method study. BMC Health Services Research, 2021, 21(1), 1331. [CrossRef]

- Naome, T.; James, M.; Christine, A. et al. Practice, perceived barriers and motivating factors to medical-incident reporting: a cross-section survey of health care providers at Mbarara regional referral hospital, southwestern Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2020, 20, 276. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K., Tian, L., Yan, C., Li, Y., Fang, H., Peihang, S., Li, P., Jia, H., Wang, Y., Kang, Z., Cui, Y., Liu, H., Zhao, S., Anastasia, G., Jiao, M., Wu, Q., & Liu, M. A cross-sectional survey on patient safety culture in secondary hospitals of Northeast China. PloS One, 2019, 14(3), e0213055. [CrossRef]

- Kakemam, E., Hajizadeh, A., Azarmi, M., Zahedi, H., Gholizadeh, M., & Roh, Y. S. Nurses’ perception of teamwork and its relationship with the occurrence and reporting of adverse events: A questionnaire survey in teaching hospitals. Journal of Nursing Management, 2021, 29(5), 1189–1198. [CrossRef]

- Lurvey, L. D.; Fassett, M. J.; & Kanter, M. H. Self-Reported Learning (SRL), a Voluntary Incident Reporting System Experience Within a Large Health Care Organization. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2021, 47(5), 288–295. [CrossRef]

- Grilli, R.; Taroni, F. Governo delle Organizzazioni Sanitarie e qualità della sicurezza. Roma, Il Pensiero Scientifico Editore, 2004.

- Müller, B. S.; Beyer, M.; Blazejewski, T.; Gruber, D.; Müller, H.; Gerlach, F. M. Improving critical incident reporting in primary care through education and involvement. BMJ Open Quality,2019, 8(3), e000556. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C., Wang, L.-H., Redley, B., Hsieh, Y.-H., Chu, T.-L., & Han, C.-Y. A Study on the Reporting Intention of Medical Incidents: A Nursing Perspective. Clinical Nursing Research, 2018, 27(5), 560–578. [CrossRef]

- Tlili, M. A.; Aouicha, W.; Sahli, J.; Zedini, C.; Ben Dhiab, M.; Chelbi, S.; Mtiraoui, A.; Said Latiri; H., Ajmi, T.; Ben Rejeb, M.; Mallouli, M. A baseline assessment of patient safety culture and its associated factors from the perspective of critical care nurses: Results from 10 hospitals. Australian Critical Care: Official Journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses, 2021, 34(4), 363–369. [CrossRef]

- Liukka, M., Hupli, M., & Turunen, H. How transformational leadership appears in action with adverse events? A study for Finnish nurse manager. Journal of Nursing Management, 2018, 26(6), 639–646. [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, C.; Rohe, J.; Heinrich, A.S.; Hahnenkamp, C.; Thomeczek, C. CIRS – Gemeinsames Lernen durch Berichts- und Lernsysteme. In: Herbig N, Poppelreuter S, Thomann H, editors. Qualitätsmanagement im Gesundheitswesen. 31. Aktualisierung. Köln: TÜV Media; 2013. p. 1–46, Anhang. Berlin: ÄZQ; 2013. (äzq Schriftenreihe; 42).

- Yoo, M. S., & Kim, K. J. Exploring the Influence of Nurse Work Environment and Patient Safety Culture on Attitudes Toward Incident Reporting. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 2017, 47(9), 434–440. [CrossRef]

- Pauletti, G., Girotto, C., De Luca, G., & Saieva, A. M. Incident reporting reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic in a tertiary Italian hospital: A retrospective analysis. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 2022, 34(2), mzab161. [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D. M., & Doucette, J. N. Impact of High-Reliability Education on Adverse Event Reporting by Registered Nurses. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 2018, 33(3), 285–290. [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, R.; Goodman, P. S. The challenge of collective learning from event analysis. Safety Science 2011, 49(1), 83–89. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M. S.; Kim, K. J. Exploring the Influence of Nurse Work Environment and Patient Safety Culture on Attitudes Toward Incident Reporting. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 2017, 47(9), 434–440. [CrossRef]

- Birkeli, G. H.; Jacobsen, H. K.; Ballangrud, R.Nurses’ experience of incident reporting culture before and after implementing the Green Cross method: A quality improvement project. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 2022, 69, 103166. [CrossRef]

- Nuckols, T.K.; Bell, D.S.; Liu, H.; Paddock, S.M.; Hilborne, L.H. Rates and types of events reported to establish incident reporting systems in two US hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007, 16, 164–8. [CrossRef]

- Panzica, M.; Krettek, C.; Cartes, M. Clinical Incident Reporting System als Instrument des Risikomanagements für mehr Patientensicherheit. Unfallchirurg. 2011, 114, 758–67. [CrossRef]

- Heideveld-Chevalking, A.J.; Calsbeek, H.; Damen, J.; Gooszen, H.; Wolff, A.P. The Impact of a standardized incident reporting system in the perioperative setting. A single center experience on 2.563 ‘near-misses’ and adverse events. Patient Saf Surg. 2014, 8(46), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cousins, D.H.; Gerrett, D.; Warner, B. A review of medication incidents reported to the National Reporting and Learning System in England and Wales over 6 years (2005–2010). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012, 74(4), 597–604. [CrossRef]

- Levtzion-Korach, O.; Frankel, A.; Alcalai, H.; Keohane, C.; Orav, J.; Graydon-Baker, E.; Barnes, J.; Gordon, K, Puopulo AL, Tomov EI, Sato L, Bates DW. Integrating incident data from five reporting systems to assess patient safety: making sense of the elephant. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010, 36(9), 402–10. [CrossRef]

- Steyrer, J.; Schiffinger, M.; Huber, C.; Valentin, A.; Strunk, G. Attitude is everything? The Impact of workload, safety climate, and safety tools on medical errors: a study of intensive care units. Health Care Manag Rev. 2013, 38(4), 306–16. [CrossRef]

- Hoffinger, G.; Horstmann, R.; Waleczek, H. Das Lernen aus Zwischenfällen lernen: Incident Reporting im Krankenhaus, Hochleistungsmanagement. München: Gabler; 2008, 207–24. [CrossRef]

- Benn, J.; Koutantji, M.; Wallace, L.; Spurgeon, P.; Rejman, M.; Healey, A.; Vincent, C. Feedback from incident reporting: information and action to improve patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009, 18(1), 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Buscemi, A. Il risk management in sanità. Gestione del rischio, errori, responsabilità professionale, aspetti assicurativi e risoluzione stragiudiziale delle controversie. Milano, Franco Angeli, 2017.

- Clanton, J.; Clark, M.; Loggins ,W.; Herron, R. Effective handoff communication. In: Firstenberg MS, Stawicki S, editors. Vignettes in patient safety. London: Inte- chOpen 2018, 2, 25-44. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Patient Safety Day. Available from https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-patient-safety-day/2022 (Accessed on July 22, 2023).

- Ministero della Salute. Risk Management in Sanità. Il problema degli errori. Roma, 2003.

| Studies | Location | Type of study | Keyword |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al Lawati, 2019 [31] | Oman | Qualitative study | Low safety culture, lower error reporting |

| Carlfjord, 2018 [32] | Sweden | Qualitative study | Improved safety culture, increased IR use |

| De Kam, 2020 [33] | Netherlands | Mixed method study | Event reporting system (IRS) increased knowledge of patient safety |

| Flott, 2018 [34] | United Kingdom | Case report | Improved event reporting process, developed basis for safety culture |

| Ghasemi, 2022 [35] | Malaysia | Case report | Positive safety culture associated with fewer verified errors |

| Petschnig & Haslinger-Baumann, 2017 [36] | Austria | Qualitative study | Incident reporting takes the form of a quality assessment tool |

| Raeissi, 2018 [37] | Iran | Qualitative study | Perception of safety culture greater than event reporting |

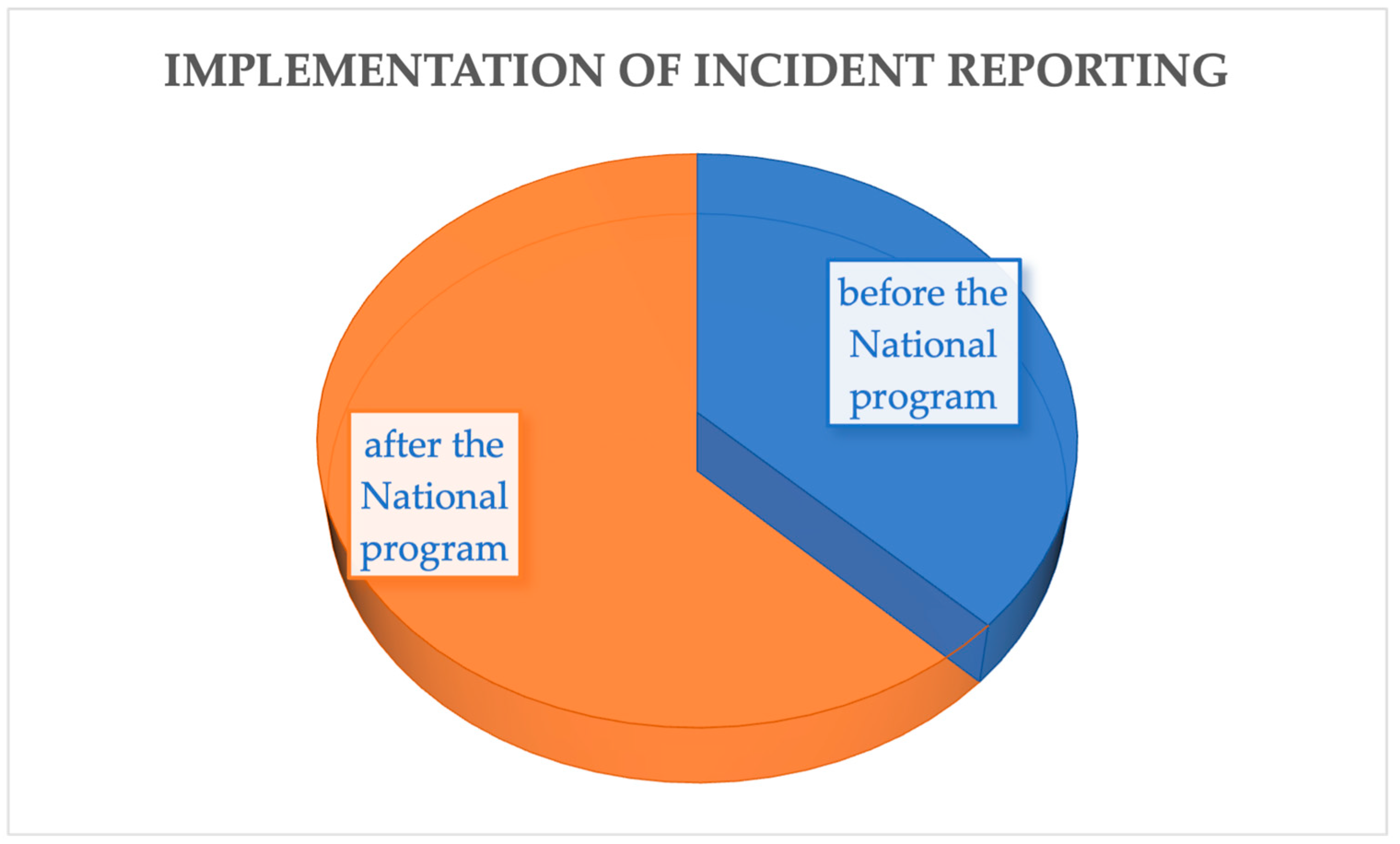

| Verbeek-van Noord, 2019 [38] | Netherlands | Cross-sectional study | Establishment of a national patient safety program, increased number of adverse event reports |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).