1. Introduction

In these uncertain times, discerning “what is next” for the higher education sector will likely require calculated speculation and some risk-taking initiatives. It is imperative to note that the COVID-19 pandemic has not only created severe short-term financial and operational challenges for institutions of higher learning, but it further accelerated the impact of demographic, financial, technological, and political structures that have been long affecting the higher education sector. While lecturers remain committed to their institutions’ core missions in the face of these challenges, now is the right time to reconsider value propositions and operating models considering new realities. This paper produced this report to help institutions navigate the uncertainties ahead.

The new urgency for remote teaching caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has created an opportunity for the country’s education structures to draft and adopt policies to accelerate blended learning practices among lecturers and students. With some higher education (HE) academic programmes offered entirely online because of the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, large-scale change has been required of academic staff who design and present the programmes and of the students who undertake them. The change and adaptability to the change were somewhat a challenge to both the teacher and the learner as less training on some LMS affordances was provided amid the pandemic. To an extent, both the lecturers and learners were learners in how to navigate the online platforms to get learning and teaching activities underway.

On-campus traditional face-to-face teaching will most likely return when the pandemic abates, providing the social-cultural elements of the teacher, the learning environment, technology, learning activities, and peers that in undergraduate education support effective student engagement ([

1] Tay et al [

14] and students’ development of higher-level skills such as problem-solving and technical skills.

It is interesting to note that during the pandemic, students’ preferences for online compared with traditional face-to-face learning and teaching activities shifted worldwide: 78% of tertiary students in Malaysia, 83% in Canada, and 78% in China indicated a preference for online learning dependent to the programme fees if were to be reduced accordingly [

16]. Globally, online learning as the panacea during the pandemic [

17] was seen in Singapore with the government’s requirement of it for the education sector including higher education institutions (HEIs) [

17]. Post-COVID-19, however, it is expected that the new educational model to emerge [

2] is blended learning (BL) which melds face-to-face teaching with online tools [

3], bridging COVID-19 fully online learning and on-campus face-to-face learning [

2]. [

4] argued that blended learning has become immensely integrated in contemporary times owing to the emergence of COVID-19. Furthermore, they stressed that blended learning is an effective approach to meet the accelerated demands of the diverse student population in universities and colleges.

Emerging from this in-depth study of the uses and perspectives of academic staff with Blended Learning in a Singaporean HEI, the systematic group of elements that constitute a BL ecosystem is identified. This ecosystem that demonstrates flexibility can guide Blended Learning development in HEIs in Singapore, and globally. The Science Foundation lecturers seemed to experience challenges in online learning platforms as learning and teaching activities and all forms of assessments were to be given and graded on the Moodle LMS. Technically, the institution-prescribed LMS was not intensively explored and used pre the covid-19 pandemic. Learning and teaching activities by then were conducted on traditional face-to-face and paper-based learning. Henceforth, the instant shift from minimal use of the Moodle LMS to being the core tool used to enhance learning and teaching within the institutions brought about challenges to both lecturers and students.

Moreover, the academics at one of the South African rural-based and historically disadvantaged universities constantly raise concerns regarding the Moodle platform in mathematics and science-related modules due to unduly accommodation in the assessments uploaded on the platform. While the institution encourages academics to regularly use Moodle over the other platforms to integrate online classes and assessments. Moreover, the assessments are mostly not easy to mark on the platform. The LMS affordances to Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) subjects seem lacking which had a negative impact and vast challenges to teaching practitioners as well as to students when they attempt some of their assessment and module core-competencies tasks.

2. Purpose of the Paper

The purpose of the paper is to examine the academics’ perspectives on a blend of a metaverse in the higher education sector in the post-COVID-19 era at one of the South African rural universities.

4. Theoretical Framework

Connectivism was first introduced in 2004 in a blog post which was later published as an article in 2005 by George Siemens. It was later expanded in 2005 by two publications, Siemens’

Connectivism: Learning as Network Creation [

5]

and Downes’

an Introduction to Connective Knowledge [

6]. Both works received significant attention in the blogosphere and an extended discourse has followed on the appropriateness of connectivism as a learning theory for the digital age. In 2007, Bill Kerr entered the debate with a series of lectures and talks on the matter, as did Forster, both at the Online Connectivism Conference at the University of Manitoba. In 2008, in the context of digital and e-learning, connectivism was reconsidered and its technological implications were discussed by Siemens and Ally.

Moreover, this theoretical framework is employed in this paper because it focuses on understanding learning in a digital age. It emphasises how internet technologies such as web browsers, search engines, wikis, online discussion forums, and social networks contributed to new avenues of learning. As technological affordance has enabled academics to learn and share information across the World Wide Web and among themselves in ways that were not possible before the digital age.

Learning does not simply happen within an individual, but within and across the networks. Connectivism perceives knowledge as a network and learning as a process of pattern recognition. The phrase "a learning theory for the digital age indicates the emphasis that connectivism gives to technology's effect on how people live, communicate, and learn. In relation to this paper, Connectivism becomes an integral part of establishing the interconnectedness between the lecturer and students with transformative principle-based pedagogy where the emphasis is on the joint construction of knowledge in a community of students through the aid of E-learning education systems and platforms.

5. Material and Methods

In this paper, a qualitative research method was employed, whereby the survey questionnaire was later quantified to determine the degree of the problem and predominant issues and challenges from academics’ responses. [

8] and [

9] attest to the significance of employing a qualitative data collection approach as being immensely effective in social sciences to study fields such as education, sociology, and anthropology. Most significantly, the utilisation momentum of this approach has been gained in the health professions and education fields. This method was used to obtain descriptive and empirical data from the respondents, and this included frequency counts and percentages to determine the most common perspectives and challenges related to the questions.

The researchers employed a purposive sampling technique because the participants were in the interest of the researcher’s criteria as they made use of technological devices during the hard lockdown period and navigated through the online space. The sample included a total of ten (10) academic staff from different departments within the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture and the four (4) E-learning practitioners at the rural University of the Limpopo Province and they were all requested to participate in the study by first signing the consent form for ethical consideration and later they completed the questionnaire and narratives.

However, only ten (10) academics and four (4) E-learning practitioners completed out of the entire population of science lecturers responded to the survey questionnaire and this survey was aimed at assessing lecturers’ experiences with digital assessments while facilitating online lectures on various platforms. The data collected for this study were analysed using thematic coding, with researchers going through the responses carefully to classify the data into topics and further understand the perspectives of academics on the usage of technology beyond the COVID-19 era in higher education institutions at a rural-based university. The researchers analysed publicly available data, surveys, and interviewed lecturers and e-learning practitioners at one of the rural universities in the South African higher education sector to large flagship public universities.

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Sociodemographic Data of the Participants

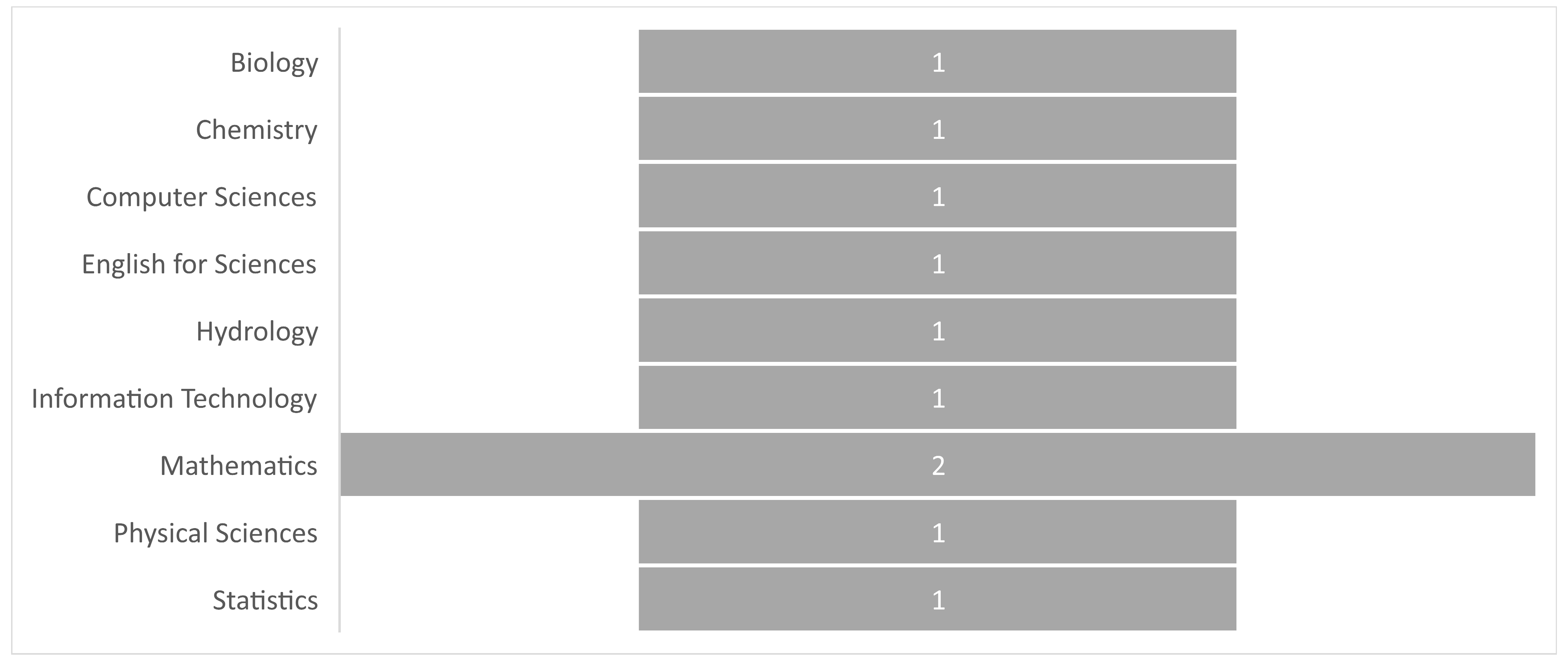

The population comprised six male academics and four female academics who are lecturing the science modules shown in

Figure 1, wherein there is an integration of Moodle LMS. Subsequently, it was quite difficult for marking digital assessments and providing timely feedback to the students. The four male E-learning practitioners were interviewed to report on their observations and challenges encountered by the academics in the different faculties within this institution.

The responsibilities of the three E-learning practitioners focused mainly on supporting staff academics with mitigation of conundrums faced during the digital engagements (

Figure 2). On the other hand, challenges around digital learning are not encountered by academics only, however, students are also affected and therefore one of the participants was responsible for the provisioning of academic support to students (

Figure 2).

Moreover, the data were collected through interviews among the lecturers in the science-related courses. Subsequently, the consultation of the report was facilitated by the E-learning practitioners to obtain the data for comprehension of the challenges observed through the teaching and learning activities. The students whom the lecturers taught were at the first-year level in the Science Foundation, Earth Sciences, and Mathematical and Computational Sciences departments at one of the rural-based universities in South Africa.

The findings of this study exhibit that there are major issues and challenges that many academics and E-learning practitioners are encountering regarding the integration of blended learning possible as the new norm even in the post-COVID-19 era in Higher Education. Technological continuity as a new normal in the post-COVID-19 era seems to be unattainable.

6.2. Moodle LMS Adoption

The table titled ‘Moodle Adoption Report’ shows the active and inactive academics in line with the minimum online presence policy within the four Faculties namely, the Faculty of Science, Engineering and, Agriculture, the Faculty of Health Sciences, the Faculty of Management Commerce and Law, and the Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education. Moreover, the report further indicated the percentage of adoption within the four faculties in the university. The Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture recorded 29, 57%, the Faculty of Management, Commerce, and Law recorded 29,09% and the Faculty of Health Sciences recorded 10,62%, and the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences reported 26, 76% in relation to the Moodle LMS usage. Nevertheless, this study focused on participants from the three departments of the Faculty of Science, Engineering, and Agriculture (

Table 1).

Interestingly, the results of the report clearly illustrated a total of 16 online active academics out of a total of all teaching staff members of the three participating departments. Frankly, this notion resulted in a huge number of 40 online inactive academics within these departments.

The usage of the Moodle LMS has deteriorated and the adoption is quite cumbersome in terms of the percentage of academics who are actively integrating blended learning. Moreover, the continuity of digital education seems to be questionable based on the current realities of usage. As such, some of the lecturers indicated that the assessments will forever need a physical setting, not an online space, particularly in rural-based and historically disadvantaged institutions whereby connectivity infrastructures seem to be a major conundrum for students from remote areas. Some honestly indicated that they are reluctant to undergo proper training for Moodle and other online platforms and their students were mostly unable to engage in the ongoing discussion during the session.

A high percentage (70%) of some academics narrated that face-to-face is better than online since one can monitor students who attend the classes while on the platform, it is difficult for the academics to trace the students who are actively engaging in the content and those who are only available for compliance (

Figure 3). Khoa et al. [

21] concur with the difficulties of student online engagement when students show no interaction during the online lecture.

On the other hand, 30% of academic participants thrived with learning the usage of Moodle platform (

Figure 3). These academics realised the significance of LMS usage as it brings up an improvement in terms of the quality of teaching (Khoa et al. 2020). Over and above, online preference of some academics resulted from the LMS benefits such as interacting with students through assigning essay assignments, testing via multiple-choice questions, provision of presentation slides prior lecturers (Khoa et al. 2020), and detecting students’ participation through the online participation register.

Furthermore, the results of this study indicate the preferred platforms (WhatsApp, Moodle, Microsoft Teams, and Google Teams) shown in

Figure 4 that academics use to supplement their teaching and learning with the students if they are not available on campus for contact sessions.

WhatsApp is mostly used than the other platforms due to students’ data challenges as they are presently not receiving incentives from the institution. Moreover, the computer labs were not accessible to the students, and they had problems with the lack of devices for online classes. Students supported the use of WhatsApp while considering their financial circumstances and lack of technological devices to attend online classes and network connectivity problems in the comfort of their learning space. As the lecturers provided feedback on students’ assessments using these platforms while interaction between the lecturers and students was quite unsatisfactory due to the network connectivity.

This resonates with Attard [

19] articulated in his study that online learning depends on the technologies used at the time and the curriculum that is being taught. The researchers suggest that the platforms and different approaches should be integrated to achieve maximum learning. Moreover, in congruence with the retrospect of studies conducted in this area, the findings of this study report that the digital competence of the users may be a solution to online learning.

6.3. Usage of the Learning Management System between Students and Academics

The e-learning practitioners expressed their concerns and major conundrums during their training, observations of minimum online presence and daily consultation with the academics and students. The students’ daily consultation had common problems which among others encompass network connectivity, struggling to login into the Moodle LMS, and inaccessibility to the assessment activities uploaded by their module lecturers. Furthermore, E-learning practitioners further elucidated that academics have challenges concerning marking assessments and providing feedback on the platform due to inadequate mastery of the platform operation and navigation skills. This study is validated by the findings of [

10] who elucidated that it is imperative to recognise the type of student enrolled in the course to design a suitable interaction system that enables the students not only to learn but even to interact among themselves. Therefore, LMS’s affordances come in handy in any prescribed learning and teaching e-platform as it determines and prescribes efficacy through use in learning activities within a course.

6.4. Complacency in the Online Setting

The findings of this paper reported that the biggest problem among others is complacency in the online setting and the academics tend to think that the online platform is conformable to constantly facilitate online classes while many students are mostly not participating and only available for compliance and procedural record keeping. Over and above, online classes have proven not to be solely independent due to the higher number of students who are not capacitated, and this poses an academic trajectory in many institutions. This study concurs with [

11] who pinpointed that face-to-face teaching has received strong support from students at all levels and has been viewed as more effective than online interaction as the lecturers and students tend to experience challenges. [

19] argued that within a learning and teaching setup, its deliverables are on a web-based learning management system, results showed that students' frustrations were found in three folds:

-

(i)

Lack of prompt feedback from the lecturer

Lack of prompt feedback denotes that students were impeded to receive proper guidance and timeous feedback on learning and teaching progress. This ultimately relates to a lack of guidance which in the long run put students at risk of not mastering concepts and not passing the module.

-

(ii)

Ambiguous instructions on the Web

Learning and teaching instruction must be explicitly stated and directed to students, however, in an online platform students find that teaching and learning activities with competing deadlines may be having ambiguous instruction and it is practically not viable to continue with the task until such time the lecturer may clarify the instructions.

-

(iii)

Technical problems

Amid online learning and teaching activities, students raised concerns about technical problems they encounter on and with the LMS platforms. These challenges cannot be resolved as expeditiously as needed; they may be escalated to e-learning support personnel. This could be frustrating to students as there may be facing an immediate need to use and participate in learning and teaching activities but fail to do so because of technical problems they encounter. Therefore, students find online support from technical at a later stage and this poses learning challenges with respect to the submission deadlines.

6.5. Fixed Mindset and Expectation

In this study, it was mainly reported that the transformative and flexible strategies and approaches were reluctant considered by the academics in their attempts to adapt to the new normal. Furthermore, the findings revealed that most academics believed that contact learning remains irreplaceable throughout generations and ages as some are technophilic. This study is incongruent with the findings of [

12], the study outlined that face-to-face learning is irreplaceable and a cornerstone of any learning institution, even if the current discourse and technological revolution require the use of eLearning. [

13] highlighted in comparison to a programme that is run online and one that is not, students who are attending their course online face a few barriers to their full participation in coursework units. Henceforth, face-to-face learning is more powerful in terms of student engagement and participation than online learning. Moreover, online learning was and is still an effective approach to meet the accelerated demands of the diverse student population in universities and colleges.

6.6. Resistance to Using Technology

The e-learning practitioners who were interviewed about their perceptions and perspectives on the continuous usage of technology in the higher education sector in the post-COVID-19 era indicated that the academics deteriorated the use of blended learning in their respective programmes. Whereas this has been necessitated by the adjustment of COVID-19 regulations imposed on the indoor gathering capacity wherein there is a resurgence in COVID-19 cases. Subsequently, the findings of this study are consistent with [

13] articulated that a major challenge for online learning is the one size fits all approach, which does not do justice to student differences.

This is further validated by the authors in [

20] elucidated that the emerging and experienced academics are reluctant in adapting to the digital transformation in their teaching practices and approaches. The researchers suggest that Online learning should be integrated with contact sessions to mitigate decontextualised teaching classrooms while technical support ought to be provided to the academics who are unable to effectively use blended learning in their teaching.

6.7. Lack of Technological Skills

Based on the findings of this study, this aspect of technological deficiency has largely been in the responses of both academics and E-learning practitioners. Most lecturers stated that they are not well equipped with the technological devices usually used for online teaching and learning environment. As academic institutions were impelled by the COVID-19 pandemic to integrate technology when facilitating lessons. However, academics made use of social media platforms to compensate for their incompetency with Moodle utilisation. Nevertheless, this strategy did not yield positive results as the students were unable to comprehend the feedback on their assessments owing to the unsatisfactory interaction with their lecturers. Significantly, there is a need for academics to be well-trained to use technology and LMS affordances skillfully and excellently. Unfortunately, [

3] posits that the online environment presents several challenges for both academic staff and students who increasingly require higher levels of technological competency and proficiency on top of their regular academic workload. This should be done to ensure that they have the necessary competencies and proficiency to use the prescribed LMS to aid their academic activities. This study corroborates with [

4] whose findings exhibited that lecturers and students are mainly not thoroughly trained to navigate the Moodle platform affordances. Moreover, it attests to [

13] espoused that technology is expected to improve access to education, reduce costs, improve the cost-effectiveness of education, and maintain the competitive advantage in recruiting students in higher education.

7. Conclusions

In line with the purpose of this study, it is crystal clear that the continuity of technology and digital learning still appears to be difficult conundrums as the academics who participated in this study, were quite unwilling to adopt transformative pedagogies and adapt to the online learning environment. Moreover, the full manifestation of technology as the new norm in the post-COVID-19 era seems not to be practically attainable owing to the challenges and issues expressed by academics and E-learning specialists. This is a prevalent area of significance because the emergency of the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the challenges in teaching and learning due to the distanced interaction. Conversely, it is imperative to note the online space was seen as a temporary learning environment because most lecturers seem not to welcome blended learning beyond the harsh COVID-19 restrictions. Even though there is a paradigm shift in terms of teaching and learning approaches. Most academics believed that contact learning remains irreplaceable throughout generations and ages as some are technophilic. Most academics made use of social media platforms to compensate for their incompetency with Moodle utilisation.

8. Recommendations and Implications for Practice

In order to enhance Lecturers’ adoption to utilise the Moodle LMS in the lectures, some managerial implications such as putting up some policies should be addressed. The policy must be implemented on the minimal online presence by the academics and students to enhance the usage of the platform. The Moodle Training should be made compulsory for both students and academics to equip them with the fundamental skills on the usage. Supplementing the training sessions, easy-to-use manuals should be developed to guide the LMS users. Additionally, it is important to encourage the usefulness of the platform by recognising and rewarding lecturers who use the platform effectively and resourcefully in the teaching process. The recognition and reward can be determined through the clear criteria for evaluating the quality of the student success rate or output after the lecturer’s adoption. Another useful indicator would be the comparison of the student scores before and after LMS usage and student satisfaction reports before and after the adoption of the LMS.

Furthermore, the formative assessments should be taken to the online platform in a semester in each module. The Moodle platform should be used to track the student’s active participation on the platform and impose penalties for those who are not actively using the tools for assessment and learning. The lack of access to devices should not be used as a stumbling block to consider e-learning as a viable option to continue with education. The connectivity challenge in rural areas should not be used as a reason to ignore the significant potential of e-learning as an enabler to access and advance education. The digital learning challenge should be prioritised to encourage the lecturers to use it always. While all academics should be advised to conduct at least 30% of their assessments on the online system to increase the usage of blended learning.

References

- Crosling, G.; Edwards, R.; Schroder, B. Internationalizing the curriculum: The implementation experience in a faculty of business and economics. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 2008, 30, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, J.; Gama-Araujo, I. Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic in education and vaccine hesitancy among students: A cross-sectional analysis from France. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammary, A.; Sheard, J.; Carbone, A. Blended learning in higher education: Three different design approaches. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2014, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitha, I.; Mokganya, M.G.; Manyage, T. Integration of blended learning in the advent of COVID-19: Online learning experiences of the science foundation students. Education Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. ASTD Learning News 2005, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, S. 2005. An introduction to connective knowledge.

- Ayebi-Arthur, K. E-learning, resilience and change in higher education: Helping a university cope after a natural disaster. E-learning and Digital Media 2017, 14, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, E.; Crisp, R.J.; Husnu, S. Support for the replicability of imagined contact effects. Social Psychology 2014, 45, 303–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, A.; Lingard, L.; Levinson, W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ 2008, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D. Teaching responsibility through physical activity; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hwakoh, Y. Internet-based distance learning in higher education. Tech Directions 2020, 62, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Long, Y. Critical thinking and the disciplines reconsidered. Higher Education Research and Development 2014, 32, 529–544. [Google Scholar]

- Gillett-Swan, J. The Challenges of Online Learning Supporting and Engaging the Isolated Learner. Journal of Learning Design. Special Issue: Business Management 2017, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.; Bahri, D.; Metzler, D.; Juan, D.C.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, C. 2021, July. Synthesizer: Rethinking self-attention for transformer models. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 10183-10192). PMLR.

- Karuppiah, K.; Sankaranarayanan, B.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K. Key challenges to sustainable humanitarian supply chains: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of educational technology systems 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Widmar, N.O. Revisiting the digital divide in the COVID-19 era. Applied economic perspectives and policy 2021, 43, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attard, M.; McArthur, A.; Riitano, D.; Aromataris, E.; Bollen, C.; Pearson, A. Improving communication between healthcare professionals and patients with limited English proficiency in the general practice setting. Australian Journal of Primary Health 2015, 21, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, N.; Kling, R. 1999. A case study of students' frustrations with a web-based distance education.

- Orlando, D.; Attar, E. Digital natives come of age: The reality of today’s early career teachers using mobile devices to teach mathematics. Mathematics Education Research Journal 2015, 28, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoa, B.T.; Ha, N.M.; Nguyen, T.V.H.; Bich, N.H. Lecturers' adoption to use the online Learning Management System (LMS): Empirical evidence from TAM2 model for Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh City Open University Journal of Science-Economics and Business Administration 2020, 10, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).