1. Introduction

Despite decades of research, medical advances and evidence-based care, general in-patient hospital mortality remains around 2% and is an integral part of everyday clinical practice. In cardiology departments, healthcare professionals manage patients who are often acutely ill and may deteriorate suddenly. An important facet of the continued effort to improve clinical practice and maintain high standards of care is the evaluation of performance and reflection on how clinical activities impact on patient outcomes. At the Cardiology Department of our institution, a monthly morbidity and mortality (M&M) meeting is held regularly as all deaths are discussed, and the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) classification of good clinical practice is documented [

1]. M&M meetings play an important role in improving accountability of mortality data, the quality of patient care and safety and may foster inter-professional learning among providers [

2,

3,

4,

5].

The M&M meetings have an educational role for physicians and other healthcare providers and can help in preventing medicolegal issues [

6]. In the process of reviewing all deaths, less common conditions will occasionally be brought to the fore. This is important for doctors and nurses in training as it helps to broaden their awareness of the clinical spectrum as a whole [

7]. Furthermore, a review of patient characteristics can help recognize which patient population is at greatest risk of death. This might inform the development of clinical protocols. In addition, identification of patterns of the causes of death may highlight areas of care which could benefit from improvements to the service. It should be acknowledged that not all deaths within a cardiology department will be cardiac in etiology. Improved triaging of patients could identify those who might be better managed elsewhere. Of note, non-cardiovascular death is responsible for up to 30% of deaths in patients hospitalized to cardiology wards with acute heart failure [

8] while Vicent and colleagues similarly reported that nearly 27% of patients dying in a cardiology department during a 5-year period had a non-cardiac cause of death [

9]. It is also relevant to ascertain length of stay and its relationship to cause of death. For example, duration of hospital admission has reported to be shorter among patients that die due to cardiovascular cause vs. those with a non-cardiovascular cause of death [

10].

In this work, we collated and analyzed the mortality records from a 10-year span of regular monthly M&M meetings in a tertiary-level cardiology department. To our best knowledge, analysis of this kind has not been reported thus far in the medical literature.

2. Materials and Methods

The Royal Stoke University Hospital is a tertiary level hospital providing more than 1300 beds while the cardiology department delivers a 24/7 primary percutaneous coronary intervention service, structural interventions, device implantations, electrophysiology, heart failure care, cardiac imaging and outpatient cardiology service. The unit serves a population of approximately 1.4 million patients and 600,000 from associated district general hospitals. The monthly M&M meeting incorporates all patients who have succumbed over the preceding month under the auspices of the department. The presentations include information about the age, sex, comorbidities, duration of hospital stay, clinical events and NCEPOD classification of care received by the patient as well as the cause of death [

11]. As a part of a clinical audit and health service evaluation, we collated data from the morbidity and mortality meeting presentations from 2010 to 2019, incorporating all of the parameters described above. Additional information was gleaned in the hospital’s electronic patient records.

Cause of death was categorized on three levels. The lowest level of cause of death was based on the description in the mortality meeting record, or clinical history when the case notes were unavailable. The next level grouped the diagnosis into one of several categories including acute myocardial infarction (AMI), AMI with non-heart failure complication, aortic stenosis (AS), AS with complication, aortic pathology, arrhythmia, isolated cardiac arrest, cardiac tamponade, heart failure, heart failure with complication (e.g. sepsis, complete heart block, bleeding, etc) or a specific cause (e.g. defined cardiomyopathy such as dilated cardiomyopathy), infective endocarditis, malignancy, other cardiac, other non-cardiac, pulmonary embolism, sepsis and stroke. The highest level then regrouped all deaths into the following: all AMI, all HF, isolated cardiac arrest, other cardiac and other non-cardiac. In order to limit bias, we initially classified the cause of death between three independent reviewers and the subgroup classifications were validated independently by a consultant.

Statistical analysis was performed on Microsoft Excel and Stata 14.0 (College Station, Tx). The proportion of each cause of death on the highest level were presented in a pie chart. The trends in the proportion for individual causes of death were also evaluated. The median length of stay and number of comorbidities along with the interquartile range is shown in a bar chart. A table was used to show the proportion of causes of death overall and according to age <65 years or age ≥65 years and whether the patient was male or female. In addition, another table was used to describe the causes of death in the lowest level for each subgroup for cause of death. Chi-square tests were used to determine differences in causes of death between older and younger patients as well as between males and females. At all instances, statistical significance (p-values) <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

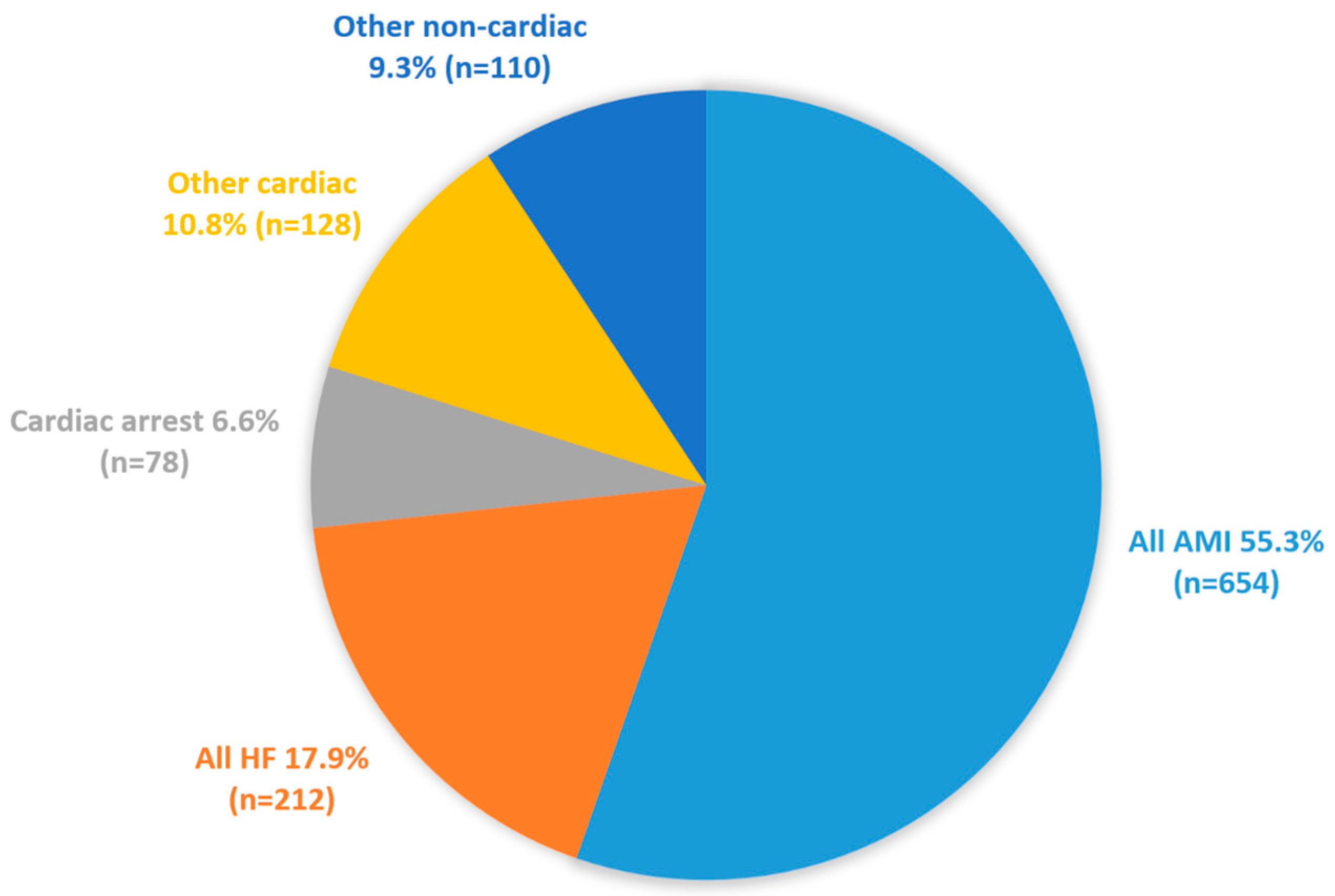

Between 2010 and 2019, 1182 deaths were captured in our mortality and morbidity meetings. The average age of death 75±25 years and 63% of patients were male. More than half of the deaths were due to acute myocardial infarction (55.3%) while heart failure (17.9%), isolated cardiac arrest (6.6%), and other causes made up the remaining causes of death (

Figure 1).

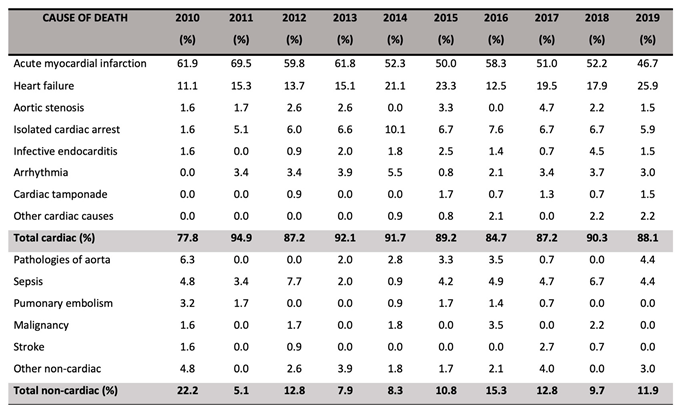

Table 1 shows the trends in cause of death over time. Comparing 2010 to 2019, there was a decrease in the proportion of deaths due to AMI (61.9% in 2010, 46.7% in 2019) and an increase in the proportion of deaths due to heart failure (11.1% in 2010, 25.9% in 2019). Cardiac causes of death made up the majority, and this proportion increased from 77.8% in 2010 to 88.1% in 2019. The median age at time of death did not increase over the years of the study which was 77 years.

Furthermore,

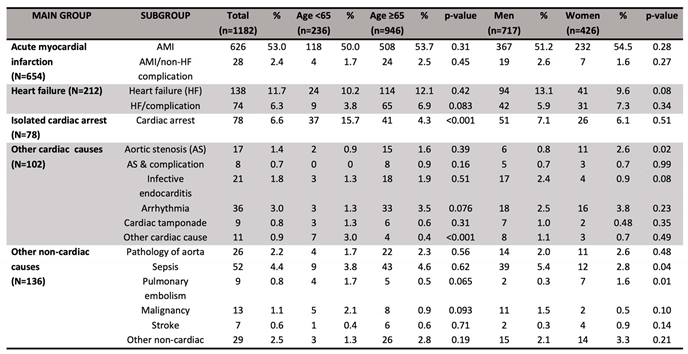

Table 2 describes the subgroups of causes of death. The ten most common causes of death were acute myocardial infarction (53.0%), heart failure (11.7%), isolated cardiac arrest (6.6%), heart failure with complication (6.3%), sepsis (4.4%), arrhythmia (3.0%), other non-cardiac (2.5%), AMI/non-HF complication (2.4%), aortic pathology (2.2%), and infective endocarditis (1.8%). Compared to older patients (age 65 years or greater), younger patients were more likely to die from isolated cardiac arrest (15.7% vs 4.3%, p<0.001) and other cardiac reasons (3.0% vs 0.4%, p<0.001). Older patients died more frequently from aortic stenosis (1.6% vs 0.9%, p=0.39), sepsis (4.6% vs 3.8%, p=0.62) and heart failure with complications (6.9% vs 3.8%, p=0.083). Men had a greater proportion of death from sepsis (5.4% vs 2.8%, p=0.038), heart failure (13.1% vs 9.6%, p=0.077) and malignancy (1.5% vs 0.5%, p=0.10) compared to women but women had proportionately more deaths from aortic stenosis (2.6% vs 0.8%, p=0.018) and pulmonary embolus (1.6% vs 0.3%, p=0.012).

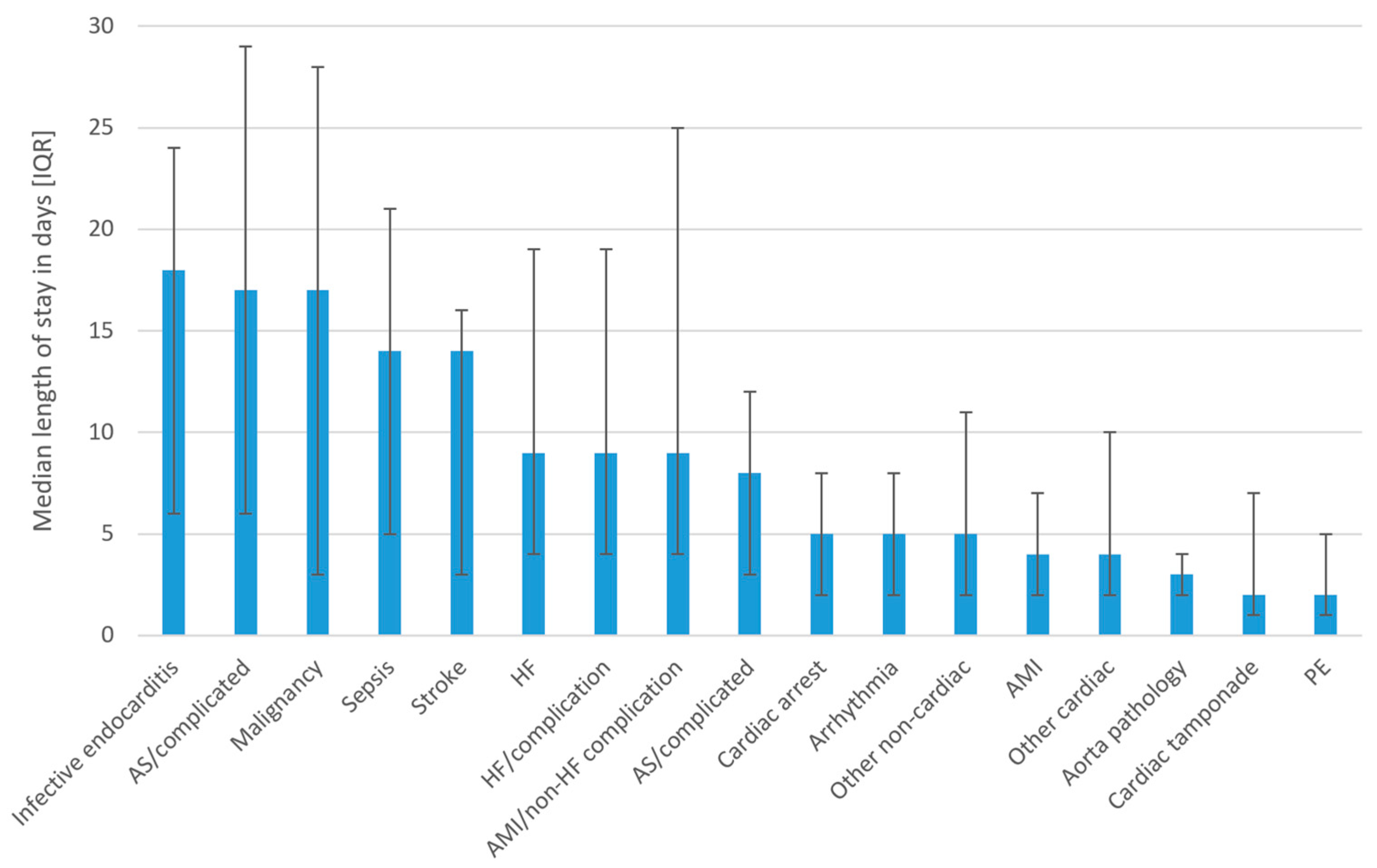

The median length of stay was greatest where death was associated with infective endocarditis, aortic stenosis with complication, malignancy, sepsis and stroke (

Figure 2). Patients who died from AMI, other cardiac, aorta pathology and cardiac tamponade had the lowest median hospital stay.

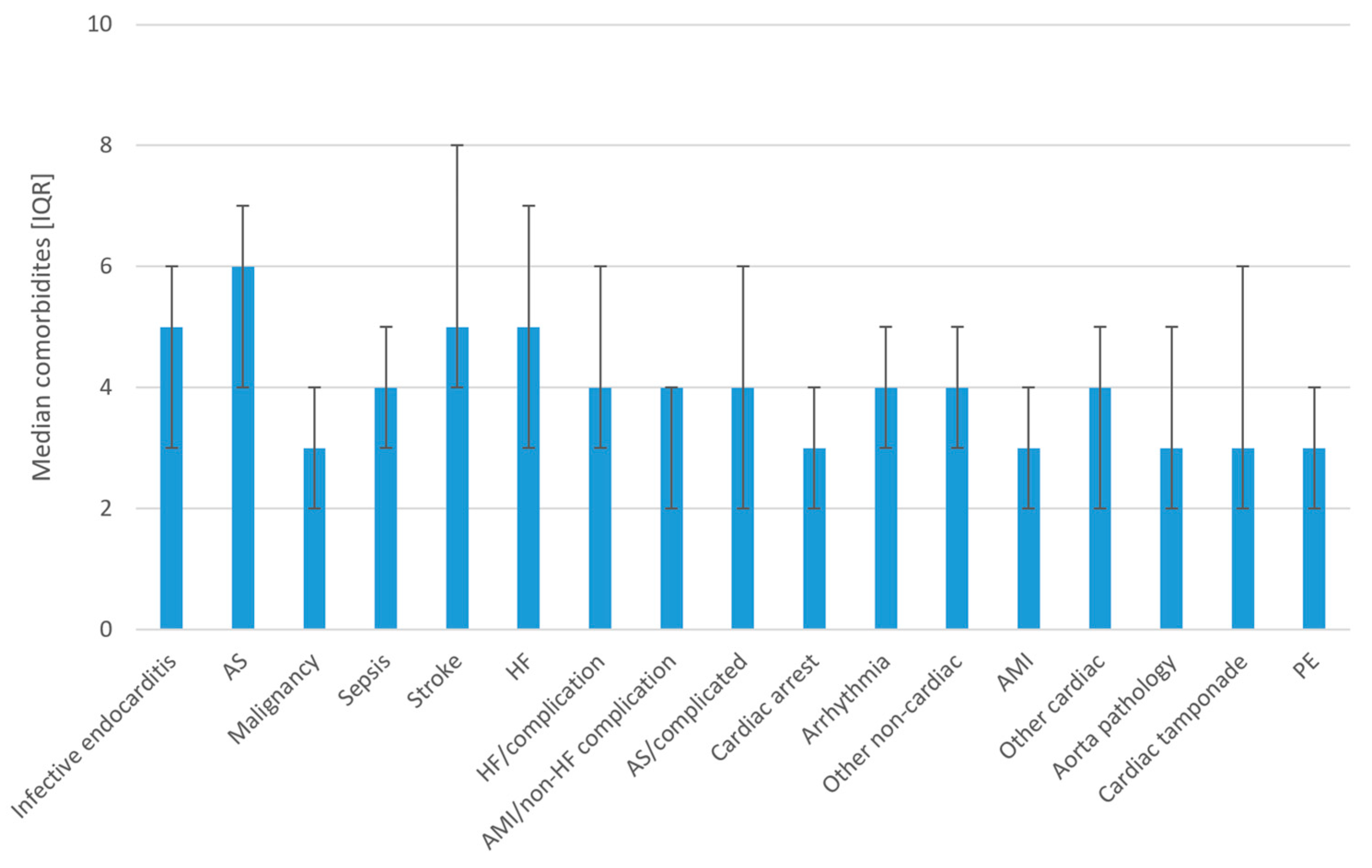

The number of comorbidities according to cause of death is shown in

Figure 3. The median number of comorbidities was greatest for the conditions such as aortic stenosis, infective endocarditis, stroke and heart failure.

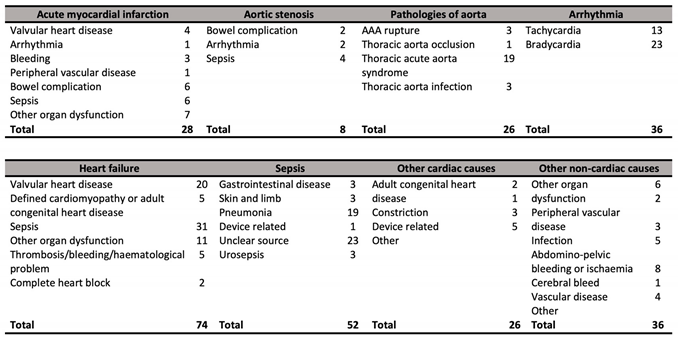

The exact cause of death in subgroups for some of the causes of death are shown in

Table 3.

For patients with AMI and non-heart failure complications, the causes of death included valvular heart disease, arrhythmia, bleeding, peripheral vascular disease, bowel complication, sepsis and other organ dysfunction. More detailed causes of death in heart failure with complications/defined cardiomyopathy included valvular heart disease, defined cardiomyopathy such as dilated cardiomyopathy or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or adult congenital heart disease, thrombosis, bleeding or complete heart block. Aortic pathology was a composite of acute aortic syndrome from dissection, abdominal aortic rupture, thoracic aortic infection and thoracic aortic occlusion.

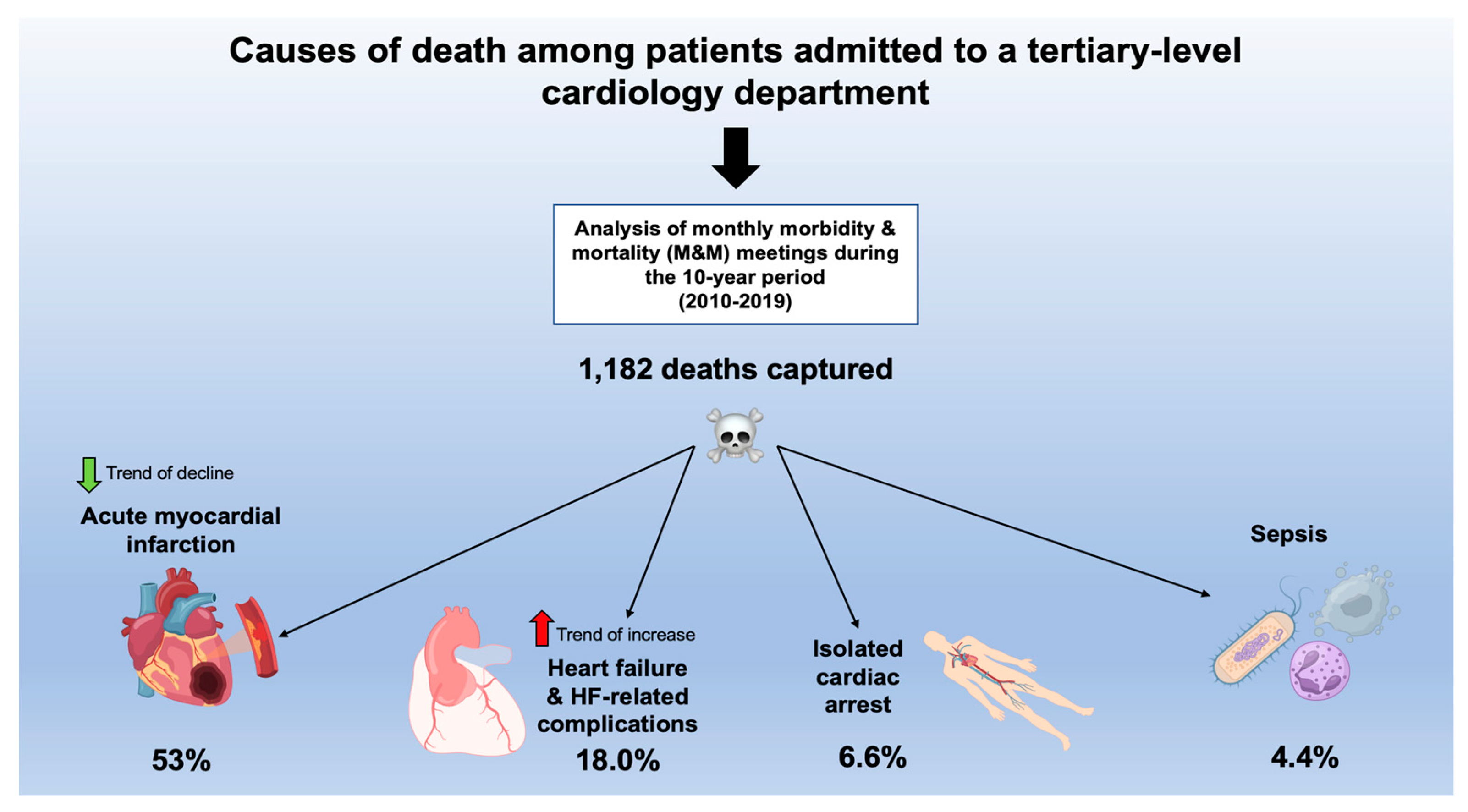

The Central Figure (

Figure 4) presents the summarized causes of death among patients admitted to a tertiary-level cardiology department.

4. Discussion

At our tertiary center, there were 1,182 deaths registered over a 10-year period which is equivalent to an annual average of 118 deaths per year. These deaths were mainly due to AMI and to a lesser extent HF and isolated cardiac arrest. In terms of trends, we observed a significant growth in the proportion of deaths from HF and a decline in the proportion due to AMI with more deaths related to cardiac disease than the non-cardiac disease in recent years. An uncommon cause of death was the pathology of the aorta but there was a notable population who had died from non-cardiac causes such as sepsis and malignancy (approximately 1 in 10 patients). Moreover, the causes of death varied according to age group as older patients have a greater proportion of deaths due to aortic stenosis, sepsis, and HF whereas younger patients were more likely to die of isolated cardiac arrest. In addition, the length of hospital stay tends to be higher among patients who died of causes such as infective endocarditis, aortic stenosis with complications, malignancy, sepsis, and stroke. These findings suggest that cardiology services should accept that a substantial portion of the mortality will be attributed to AMI, HF, and isolated cardiac arrest but healthcare professionals should also be prepared to diagnose and manage patients with rare cardiac pathologies and non-cardiac diseases.

Some interesting remarks can be made regarding the trends in mortality observed in our study. It is a well-known fact that mortality due to AMI has decreased significantly worldwide over the last century [

12,

13,

14]. This decline in MI-related deaths is largely attributed to better care of patients with AMI which has culminated in the contemporary practice of 24-hour/7 primary PCI service and the routine use of potent antithrombotic and secondary prevention medications. The consequences of improved survival among patients with AMI may result in a growing population of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy who may, later on, present with HF. This is consistent with the epidemiological findings regarding HF mortality where there has been a growth in the proportion of patients that are dying from HF in past few decades [

15,

16].

Our study also provides insight into complications and less common but important contributors to death. Pathologies of the aorta including aortic dissection, thoracic or abdominal aorta rupture, aortic occlusion and infections of the aneurysms are contributors to death which may have had multidisciplinary care with cardiac surgeons. Of importance, it has been recently recognized that deaths from aortic dissection now outnumber deaths from road traffic collisions in the UK [

17]. The major single arrhythmia event accounting for death was complete heart block and many of these patients died despite receiving a pacemaker device because of coexisting significant comorbidities and/or frailty. It may well be that cardiac conduction disease is part of an end-stage of other comorbidities and general frailty and thus might not have been correctable by pacemaker implantation alone.

We observed that gastrointestinal complications are not uncommon contributors to death among patients admitted to the Cardiology department. These pathologies include gastrointestinal bleeding, bowel obstruction, bowel perforation, ischemic colitis, ischemic hepatitis, acute cholangitis, and biliary sepsis. In addition, renal dysfunction is common in AMI and HF patients due to the combination of kidney hypoperfusion and the use of diuretics [

18,

19]. Infections remain common contributors to death, the most frequent being a chest infection. It has been reported that sepsis is the most prevalent cause of death from all hospital admissions in a six-center study in the United States [

20]. Furthermore, factors such as advanced frailty, comorbidity, and advanced age seem to be predominant characteristics of hospitalized patients treated for infection, regardless if they had sepsis or not [

21]. Rare causes of death in our sample included chronic multisystem disorders such as sarcoidosis and amyloidosis with one patient dying due to constrictive pericarditis and one from VT storm. There were also a few cases of patients dying from iatrogenic complications including infected shunts or implanted devices and cardiac perforation due to pacing lead insertion. Another heterogeneous population was adult patients with congenital heart disease as there were cases with Eisenmenger syndrome and Tetralogy of Fallot. From an educational perspective, it is important that less experienced clinicians are aware of how to manage these rare but important pathologies that occur in clinical practice.

We observed differences in the proportion of death by age group. Younger patients with underlying heart disease may present for the first time with isolated cardiac arrest. We accept that there may be an age-related selection bias for admissions to a specialist cardiology ward. Older patients that present with cardiac arrest usully have an underlying coronary artery disease whereas younger patients tend to have structural heart disease and/or arrhythmogenic disorders [

22,

23]. Out of these young patients, there was one cardiac arrest event that resulted in death in whom arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy was identified. Similarly, another young patient died after having an isolated cardiac arrest but it was noted on their records that they had asymptomatic long QT syndrome. There were also two young patients who died from viral dilated cardiomyopathy while waiting for a heart transplant and viral myocarditis which was initially treated as acute coronary syndrome. On the other hand, older patients had a greater proportion of deaths from aortic stenosis and some of these patients had undergone transcatheter valve implantation. Elderly patients have significantly greater comorbidity burden and are prone to infections due to frailty [

24,

25].

This study has some limitations. One of the limits of our analysis is the designation of the cause of death. Firstly, the precise cause of death was not always investigated or confirmed by the autopsy. This was the case of isolated cardiac arrest as it is typically secondary to a pathology whether it was by a hypoxic, thrombotic, or metabolic mechanism. Secondly, there are also cases where multiple pathologies and comorbidities complicated the exact adjudication of the cause of death. We used a ranking system such that where the history was consistent with AMI as the initial insult causing hospitalization the cause of death was considered to be AMI even though later non-cardiac complications such as renal failure or hospital-acquired infection may have supervened. However, to prevent the omission of these important complications we included categories of AMI with non-heart failure complications, HF with complications, and AS with complications. Because heart failure is a natural sequela of AMI we also only considered non-HF-related complications. Also, there were patients who had a life-limiting illness such as end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or lung malignancy who presented with chest pain and cardiac pathology. While end-stage chronic lung disease and malignancy contribute to death, we classified the cause of death as related to acute cardiac pathology unless the history indicated that the non-cardiac problem was the primary cause. Finally, the quality of the data was limited by the quality of the description from the PowerPoint presentations prepared by the cardiology registrars and there was a degree of missing data. In some cases, we were able to input missing data by reviewing the electronic medical records. Classification of the cause of death is complex but measures were undertaken to limit potential bias. However, we believe that our findings provide a unique insight into causes of death among patients admitted to the cardiology department at the tertiary medical center, derived from morbidity and mortality meetings as such analysis is unavailable in the literature.

Our findings bear implications for clinical practice. The identification of rare causes of death and discussing their management may help improve future practice for less experienced clinicians. Also, there are pathologies that benefit from multidisciplinary input: for example, cardiothoracic surgeons could share care for patients with aortic pathology. Furthermore, clinicians in the cardiology department reviewing deteriorating patients need to be aware of potential gastrointestinal complications as prompt detection and referral for gastroenterology or general surgical input may improve outcomes. There are also training implications as cardiology heads towards more subspecialist training it remains important that cardiologists are grounded in general medicine and are able to manage general medical emergencies such as gastrointestinal bleeding and sepsis.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, most of the deaths at our cardiology departments were due to AMI, HF, and isolated cardiac arrests while the proportion of causes of deaths varied depending on the age group where younger patients had a significantly greater proportion of deaths from isolated cardiac arrest. These findings suggest that tertiary cardiology services should be prepared to manage acutely ill patients with AMI, HF, and isolated cardiac arrests but also to investigate and manage patients with less common cardiac pathologies and non-cardiac diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.K; methodology, C.S.K and J.A.B; validation, C.S.K. and J.A.B; formal analysis, C.S.K.; investigation, C.S.K., J.T., C.W.W., S.B., D.Z., A.M.D., D.S., M.G., J.A.B.; resources, J.A.B..; data curation, C.S.K..; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.K..; writing—review and editing, C.S.K., J.T., C.W.W., S.B., D.Z., A.M.D., D.S., M.G., J.A.B.; visualization, C.S.K. and J.A.B..; supervision, C.S.K..; funding acquisition, J.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that data for this study were part of a routine service evaluation that does not require special approval from our local IRB.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the fact that data for this study were part of a routine service evaluation that does not require special approval from our local IRB. all data are fully anonymized and no participating patients can be identified.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Derrington, M.C.; Gallimore, S. The effect of the National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths on clinical practice. Report of a postal survey of a sample of consultant anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 1997, 52, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesbrecht, V.; Au, S. Morbidity and Mortality Conferences: A Narrative Review of Strategies to Prioritize Quality Improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016, 42, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Higginson, J.; Walters, R.; Fulop, N. Mortality and morbidity meetings: an untapped resource for improving the governance of patient safety? BMJ Qual Saf. 2012, 21, 576–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bal, G.; Sellier, E.; Tchouda, S.D.; et al. Improving quality of care and patient safety through morbidity and mortality conferences. J Healthc Qual. 2014, 36, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ksouri, H.; Balanant, P.Y.; Tadié, J.M.; Heraud, G.; Abboud, I.; Lerolle, N.; Novara, A.; Fagon, J.Y.; Faisy, C. Impact of morbidity and mortality conferences on analysis of mortality and critical events in intensive care practice. Am J Crit Care. 2010, 19, 135–45. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, N.E. Morbidity and mortality conferences: Their educational role and why we should be there. Surg Neurol Int. 2012, 3, S377–S388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J. Medical morbidity and mortality conferences: past, present and future. Postgrad Med J. 2017, 93, 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi, K.; Ikeda, N.; Kajimoto, K.; et al. Trends and predictors of non-cardiovascular death in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2018, 250, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, L.; Bru√±a, V.; Devesa, C.; et al. Seasonality in Mortality in a Cardiology Department: A Five-Year Analysis in 500 Patients. Cardiology. 2019, 142, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicent, L.; Bru√±a, V.; Devesa, C.; et al. An overview of end-of-life issues in a cardiology department. Is the mode of death worse in the cardiac intensive care unit? J Geriatr Cardiol. 2019, 16, 482–489. [Google Scholar]

- National confidential enquiry into patient outcome and death. Available online: https://www.ncepod.org.uk/grading.html (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Braunwald, E. The treatment of acute myocardial infarction: the Past, the Present, and the Future. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012, 1, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforgia, P.L.; Auguadro, C.; Bronzato, S.; et al. The Reduction of Mortality in Acute Myocardial Infarction: From Bed Rest to Future Directions. Int J Prev Med. 2022, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dani, S.S.; Lone, A.N.; Javed, Z.; et al. Trends in Premature Mortality From Acute Myocardial Infarction in the United States, 1999 to 2019. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e021682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, T.J.; Khan Minhas, A.M.; Greene, S.J.; et al. Trends in Heart Failure-Related Mortality Among Older Adults in the United States From 1999-2019. JACC Heart Fail. 2022, 10, 851–859. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, V.L. Epidemiology of Heart Failure: A Contemporary Perspective. Circ Res. 2021, 128, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Society for cardiothoracic surgery in Great Britain and Ireland. Aortic dissection kills more people in the UK than road traffic accidents. Available at: https://scts.org/aortic-dissection-kills-more-people-in-the-uk-than-road-traffic-accidents/. Last accessed. 21 September.

- Chahal, R.S.; Chukwu, C.A.; Kalra, P.R.; et al. Heart failure and acute renal dysfunction in the cardiorenal syndrome. Clin Med (Lond). 2020, 20, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kumler, T.; Gislason, G.H.; Kober, L.; et al. Renal function at the time of a myocardial infarction maintains prognostic value for more than 10 years. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011, 11, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, C.; Jones, T.M.; Hamad, Y.; et al. Prevalence, Underlying Causes, and Preventability of Sepsis-Associated Mortality in US Acute Care Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019, 2, e187571. [Google Scholar]

- Torvik, M.A.; Nymo, S.H.; Nymo, S.H.; et al. Patient characteristics in sepsis-related deaths: prevalence of advanced frailty, comorbidity, and age in a Norwegian hospital trust. Infection. In press. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, R.D.; Weintraub, R.G.; Ingles, J.; et al. A Prospective Study of Sudden Cardiac Death among Children and Young Adults. N Engl J Med. 2016, 374, 2441–52. [Google Scholar]

- Eckart, R.E.; Shry, E.A.; Burke, A.P.; et al. Sudden death in young adults: an autopsy-based series of a population undergoing active surveillance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Villanueva, P.; Salamanca, J.; Rojas, A.; et al. Importance of frailty and comorbidity in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017, 14, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esme, M.; Topeli, A.; Yavuz, B.B.; et al. Infections in the Elderly Critically-Ill Patients. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).