Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

31 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

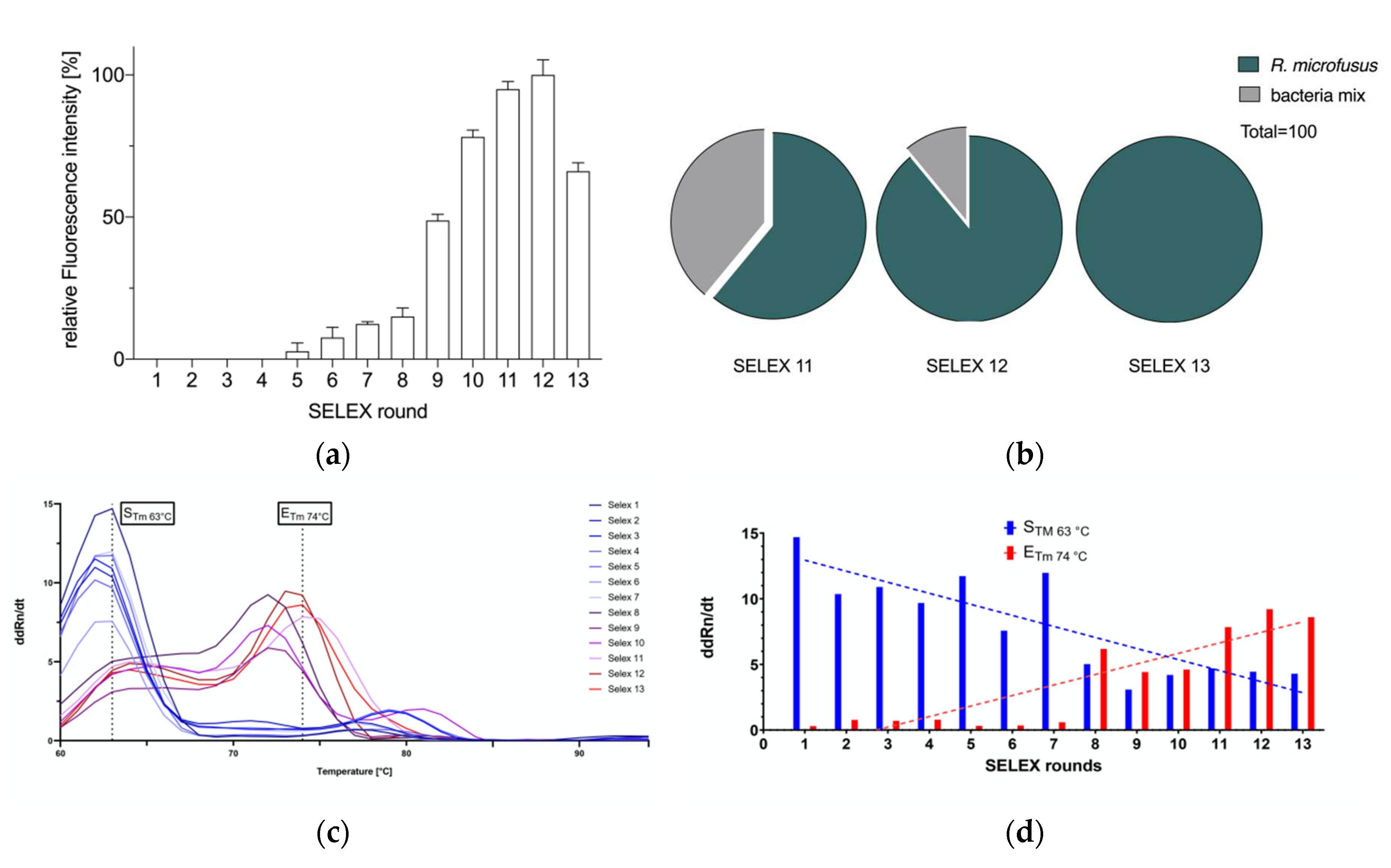

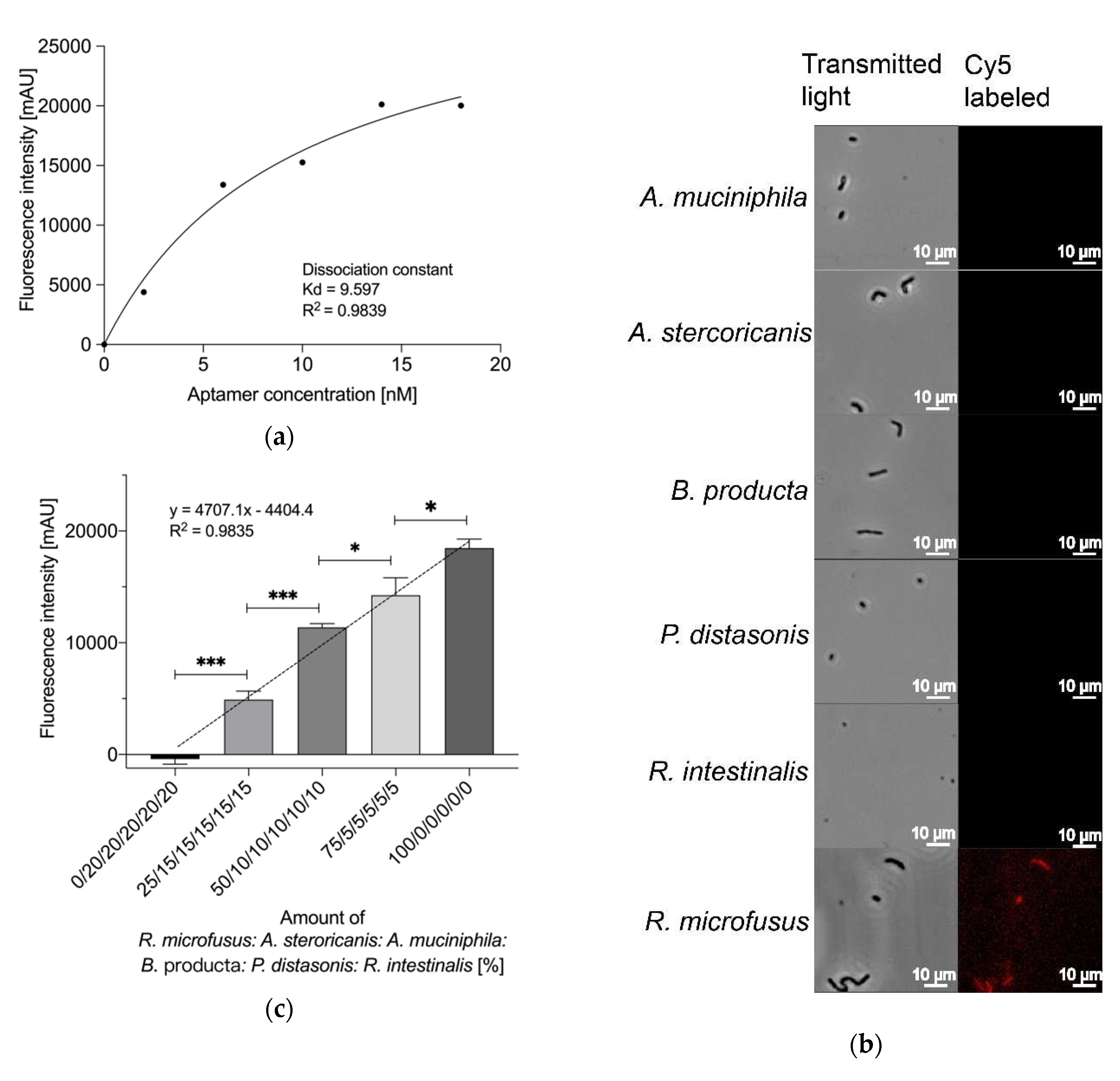

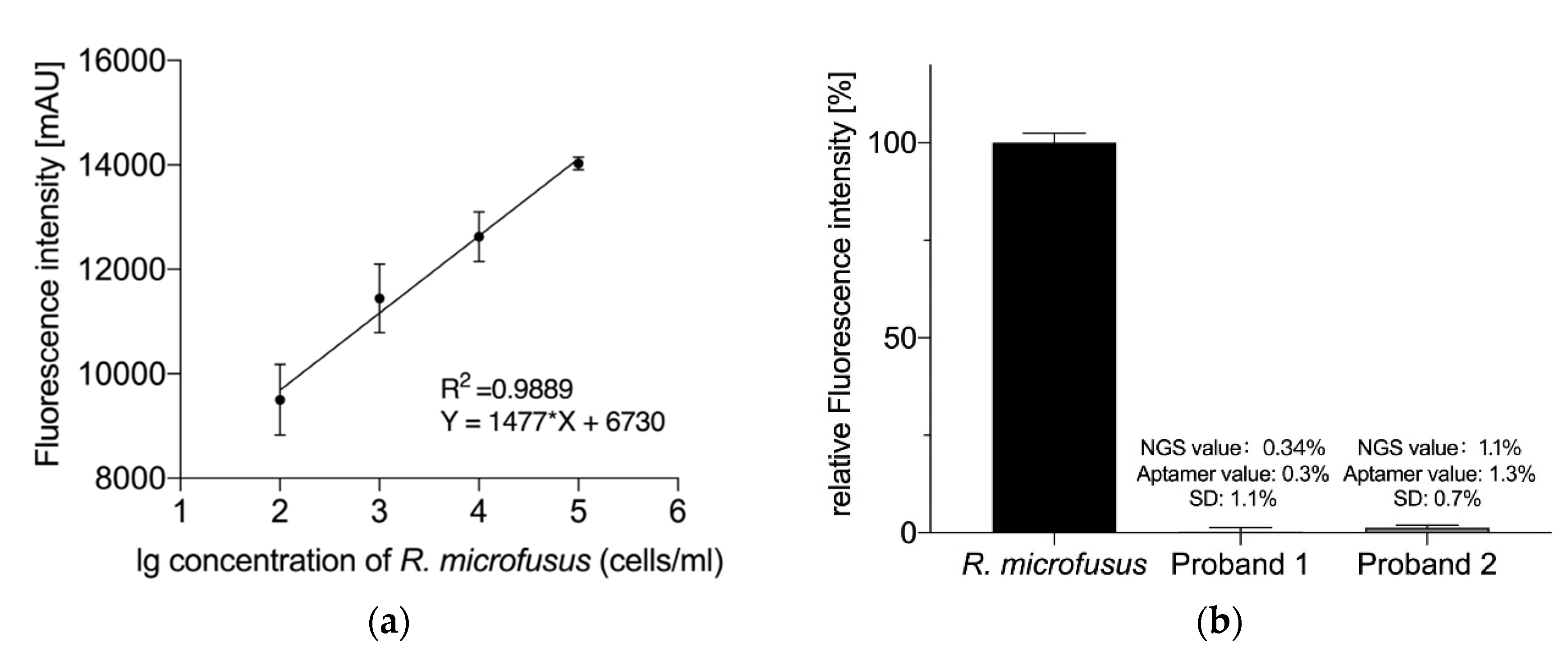

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Cell Culture

4.2. Cell Lines and Cell Culture

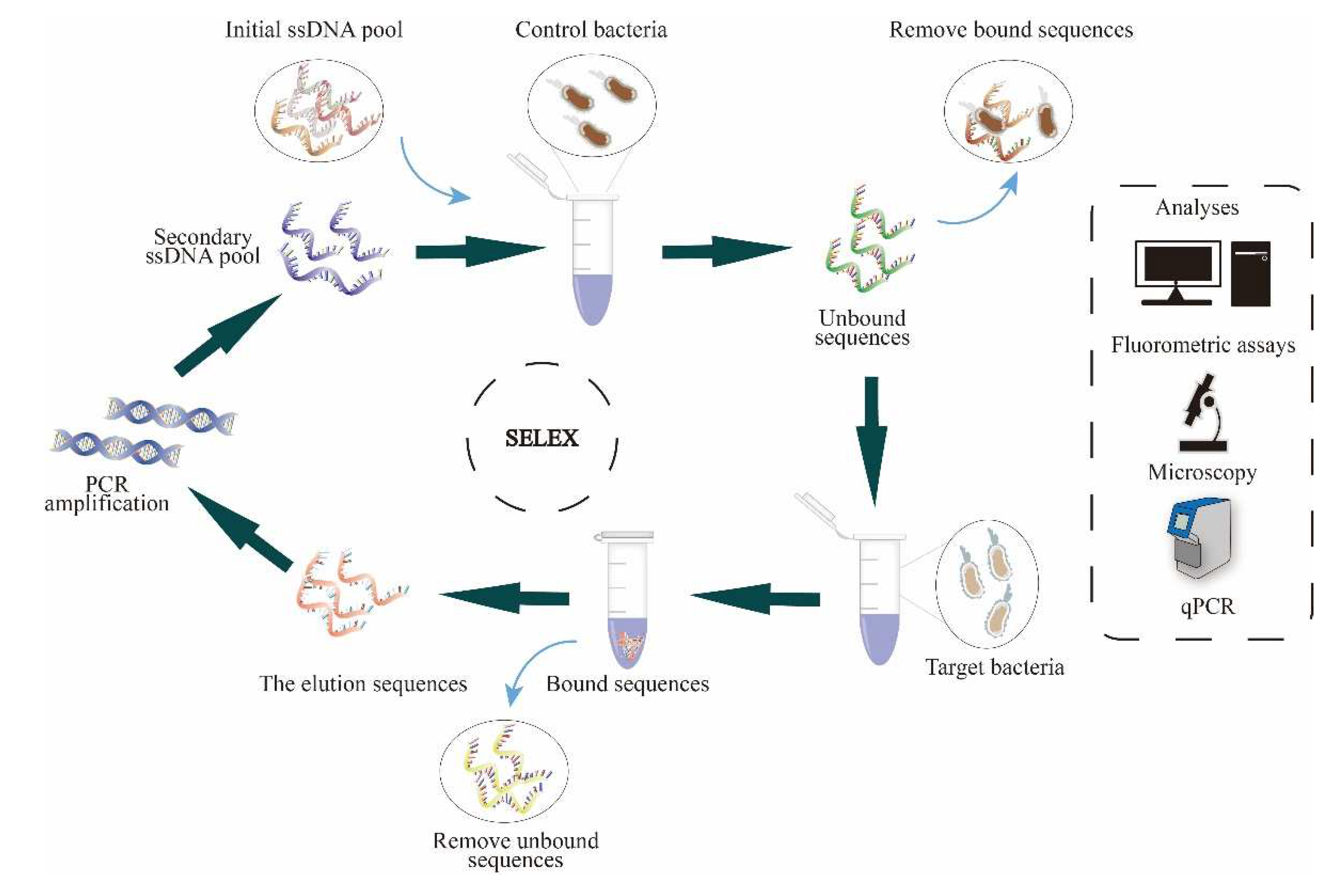

4.3. Cell-SELEX

4.3.1. Cell Pretreatment

4.3.2. Aptamer Library Activation

4.3.3. Screening

4.3.4. Elution

4.3.5. Acquisition of Secondary Libraries

4.3.6. Binding Assay

4.4. Determination of High Specificity Aptamer Libraries

4.4.1. Semi-Quantitative Analysis of R. microfusus

4.4.2. Affinity Analysis

4.4.3. Fluorescence Microscopy

4.4.4. Real-Time PCR

4.5. Analysis of R. microfusus Abundance in Human Stool Samples

4.5.1. Human Stool Samples

4.5.2. Stool Bacteria Extraction

4.5.3. Analysis Based on NGS

4.5.4. Analysis Based on the Aptamer Library R.m-R13

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Yun, C.; Pang, Y.; Qiao, J. The impact of the gut microbiota on the reproductive and metabolic endocrine system. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Feng, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Q.; Cai, L. The gut microbiota and its interactions with cardiovascular disease. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, G.; Huang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, B. The Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2017, 58, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHOJI KANEUCHI, T.M. Bacteroides microfusus, a New Species from the Intestines of Calves, Chickens, and Japanese Quails. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 1978, 28, 478–481. [Google Scholar]

- Gargari, G.; Taverniti, V.; Balzaretti, S.; Ferrario, C.; Gardana, C.; Simonetti, P.; Guglielmetti, S. Consumption of a Bifidobacterium bifidum Strain for 4 Weeks Modulates Dominant Intestinal Bacterial Taxa and Fecal Butyrate in Healthy Adults. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5850–5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopetuso, L.R.; Petito, V.; Graziani, C.; Schiavoni, E.; Sterbini, F.P.; Poscia, A.; Gaetani, E.; Franceschi, F.; Cammarota, G.; Sanguinetti, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota in Health, Diverticular Disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Time for Microbial Marker of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Dig. Dis. 2017, 36, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, X.C.; Tickle, T.L.; Sokol, H.; Gevers, D.; Devaney, K.L.; Ward, D.V.; A Reyes, J.; A Shah, S.; LeLeiko, N.; Snapper, S.B.; et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R79–R79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zeng, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Mou, F.; Wang, H.; Zou, Q.; Zhong, B.; Wu, L.; Wei, H.; et al. Role of the Gut Microbiome in Modulating Arthritis Progression in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.M.; Yamanishi, S.; Sohn, J.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Leung, J.M.; Cho, I.; Kim, S.G.; Li, H.; Gao, Z.; Mahana, D.; et al. Altering the Intestinal Microbiota during a Critical Developmental Window Has Lasting Metabolic Consequences. Cell 2014, 158, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Peng, Z.; Chen, L.; Nüssler, A.K.; Liu, L.; Yang, W. Deoxynivalenol, gut microbiota and immunotoxicity: A potential approach? Food Chem Toxicol 2018, 112, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Possemiers, S.; Van de Wiele, T.; Guiot, Y.; Everard, A.; Rottier, O.; Geurts, L.; Naslain, D.; Neyrinck, A.; Lambert, D.M.; et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 2009, 58, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Pang, X.; Xu, J.; Kang, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Structural Changes of Gut Microbiota during Berberine-Mediated Prevention of Obesity and Insulin Resistance in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e42529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yan, Y.; Huang, J.; Yin, B.; Pan, Y.; Ma, L. Cortex Phellodendri extract’s anti-diarrhea effect in mice related to its modification of gut microbiota. BioMedicine 2019, 123, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, B.; Yang, P.; Liu, Z. Herbal Formula-3 ameliorates OVA-induced food allergy in mice may via modulating the gut microbiota. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 5812–5823. [Google Scholar]

- Palmas, V.; Pisanu, S.; Madau, V.; Casula, E.; Deledda, A.; Cusano, R.; Uva, P.; Vascellari, S.; Loviselli, A.; Manzin, A.; et al. Gut microbiota markers associated with obesity and overweight in Italian adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leylabadlo, H.E.; Sanaie, S.; Heravi, F.S.; Ahmadian, Z.; Ghotaslou, R. From role of gut microbiota to microbial-based therapies in type 2-diabetes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 81, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.; Feng, Q.Q.; Ojo, O.O.; Wang, X.H. The Role of Dietary Fibre in Modulating Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Fei, J.; Xu, Q.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Gu, H.F. Interaction between Plasma Metabolomics and Intestinal Microbiome in db/db Mouse, an Animal Model for Study of Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Kidney Disease. Metabolites 2022, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.; Kesper, M.S.; Marschner, J.A.; Konrad, L.; Ryu, M.; Kumar Vr, S.; Kulkarni, O.P.; Mulay, S.R.; Romoli, S.; Demleitner, J.; et al. Intestinal Dysbiosis, Barrier Dysfunction, and Bacterial Translocation Account for CKD-Related Systemic Inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 28, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Richards, E.M.; Pepine, C.J.; Raizada, M.K. The gut microbiota and the brain–gut–kidney axis in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.-T.; Ye, X.-L.; Li, R.-R.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yong, H.-J.; Pan, M.-L.; Lu, W.; Tang, Y.; Miao, H.; et al. Resveratrol Modulates the Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Protect Against Diabetic Nephropathy in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, H.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, W.; Tan, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pei, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W. The role of the gut microbiota in depressive-like behavior induced by chlorpyrifos in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 250, 114470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsyr, O.; Maestre-Carballa, L.; Lluesma-Gomez, M.; Martinez-Garcia, M.; Cuenca, N.; Lax, P. Retinitis pigmentosa is associated with shifts in the gut microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, S.; Taylor, A. The Role of Microbiota in Retinal Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2018; 1074, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, D.M.; Volpe, G.E.; Duffalo, C.; Bhalchandra, S.; Tai, A.K.; Kane, A.V.; Wanke, C.A.; Ward, H.D. Intestinal Microbiota, Microbial Translocation, and Systemic Inflammation in Chronic HIV Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 211, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozupone, C.A.; Li, M.; Campbell, T.B.; Flores, S.C.; Linderman, D.; Gebert, M.J.; Knight, R.; Fontenot, A.P.; Palmer, B.E. Alterations in the Gut Microbiota Associated with HIV-1 Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, E.A.; Keshavarzian, A.; Losurdo, J.; Swanson, G.; Siewe, B.; Forsyth, C.; French, A.; DeMarais, P.; Sun, Y.; Koenig, L.; et al. A Compositional Look at the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Immune Activation Parameters in HIV Infected Subjects. PLOS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; Dunham, R.M.; Iwai, S.; Maher, M.C.; Albright, R.G.; Broadhurst, M.J.; Hernandez, R.D.; Lederman, M.M.; Huang, Y.; Somsouk, M.; et al. Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with HIV Disease Progression and Tryptophan Catabolism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 193ra91–193ra91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, P.-C.; Yu, K.; Dey, K.K.; Yarbro, J.M.; Han, X.; Lutz, B.M.; Rao, S.; et al. Deep Multilayer Brain Proteomics Identifies Molecular Networks in Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Neuron 2020, 105, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wu, J.; Dong, X.; Yin, H.; Shi, X.; Su, S.; Che, B.; Li, Y.; Yang, J. Gut flora-targeted photobiomodulation therapy improves senile dementia in an Aß-induced Alzheimer’s disease animal model. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2021, 216, 112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Hou, T.; Zhou, M.; Cen, Q.; Yi, T.; Bai, J.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota may be involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathology by dysregulating pyrimidine metabolism in APP/PS1 mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 967747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimjee, S.M.; White, R.R.; Becker, R.C.; Sullenger, B.A. Aptamers as Therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2017, 57, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Z.; Roslan, M.A.M.; Shukor, M.Y.A.; Halim, M.; Yasid, N.A.; Abdullah, J.; Yasin, I.S.M.; Wasoh, H. Advances in Aptamer-Based Biosensors and Cell-Internalizing SELEX Technology for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Application. Biosensors 2022, 12, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment: RNA Ligands to Bacteriophage T4 DNA Polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Keefe, A.D.; Liu, R.; Wilson, D.S.; Szostak, J.W. Constructing high complexity synthetic libraries of long ORFs using In Vitro selection. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 297, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, N.; Kuznetsov, A. Inside the Black Box: What Makes SELEX Better? Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczek, D.; Raber, H.; Bodenberger, N.; Oswald, T.; Sahan, M.; Mayer, D.; Wiese, S.; Stenger, S.; Weil, T.; Rosenau, F. The Diversity of a Polyclonal FluCell-SELEX Library Outperforms Individual Aptamers as Emerging Diagnostic Tools for the Identification of Carbapenem Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chemistry 2020, 26, 14536–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, H.F.; Kubiczek, D.H.; Bodenberger, N.; Kissmann, A.K.; D'Souza, D.; Xing, H.; Mayer, D.; Xu, P.; Knippschild, U.; Spellerberg, B.; et al. FluCell-SELEX Aptamers as Specific Binding Molecules for Diagnostics of the Health Relevant Gut Bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Kissmann, A.-K.; Raber, H.F.; Krämer, M.; Amann, V.; Kohn, K.; Weil, T.; Rosenau, F. Polyclonal Aptamers for Specific Fluorescence Labeling and Quantification of the Health Relevant Human Gut Bacterium Parabacteroides distasonis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Zhang, Y.; Krämer, M.; Kissmann, A.-K.; Amann, V.; Raber, H.F.; Weil, T.; Stieger, K.R.; Knippschild, U.; Henkel, M.; et al. A Polyclonal Aptamer Library for the Specific Binding of the Gut Bacterium Roseburia intestinalis in Mixtures with Other Gut Microbiome Bacteria and Human Stool Samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Zhang, Y.; Krämer, M.; Kissmann, A.-K.; Henkel, M.; Weil, T.; Knippschild, U.; Rosenau, F. A Polyclonal Selex Aptamer Library Directly Allows Specific Labelling of the Human Gut Bacterium Blautia producta without Isolating Individual Aptamers. Molecules 2022, 27, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J.J. Evolution of Cell-Type-Specific RNA Aptamers Via Live Cell-Based SELEX. Methods Mol Biol, 2016; 1421, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.Y. Potential for Monitoring Gut Microbiota for Diagnosing Infections and Graft-versus-Host Disease in Cancer and Stem Cell Transplant Patients. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, N.; Jolly, P.; Formisano, N.; Estrela, P. Introduction to biosensors. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Zhuo, Z.; Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Li, D.; Wan, Y.; et al. Recent Progress in Aptamer Discoveries and Modifications for Therapeutic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 13, 9500–9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulinejad, S.; Gargari, S.L.M. Aptamer-nanobody based ELASA for specific detection of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 231, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, P.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.-K. Nucleic acid aptamers targeting cell-surface proteins. Methods 2011, 54, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.W.; Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Phylogeny, culturing, and metagenomics of the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissmann, A.-K.; Andersson, J.; Bozdogan, A.; Amann, V.; Kraemer, M.; Xing, H.; Raber, H.F.; Kubiczek, D.H.; Aspermair, P.; Knoll, W.; et al. Polyclonal aptamer libraries as binding entities on a graphene FET based biosensor for the discrimination of apo- and holo-retinol binding protein 4. Nanoscale Horizons 2022, 7, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilja, S.; Stoll, C.; Krammer, U.; Hippe, B.; Duszka, K.; Debebe, T.; Höfinger, I.; König, J.; Pointner, A.; Haslberger, A. Five Days Periodic Fasting Elevates Levels of Longevity Related Christensenella and Sirtuin Expression in Humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).