Submitted:

28 July 2023

Posted:

31 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Hardware whose design is made publicly available so that anyone can study, modify, distribute, make, and sell the design or hardware based on that design. The hardware’s source, the design from which it is made, is available in the preferred format for making modifications to it. Ideally, open source hardware uses readily-available components and materials, standard processes, open infrastructure, unrestricted content, and open-source design tools to maximize the ability of individuals to make and use hardware. Open source hardware gives people the freedom to control their technology while sharing knowledge and encouraging commerce through the open exchange of designs.

2. Methods

2.1. Case Study 1: EU Firm Patenting Thermoplastics

2.2. Case Study 2: A U.S. Government Lab Patenting a European Open Source Hangprinter

2.3. Case study 3: Bambu Lab, a Chinese Company Patenting the Basic Building Blocks of Additive Manufacturing

- Patent no. CN114043726A (China)– “Method and apparatus for 3D printing, storage medium, and program product” filed on 11th November 2021, current status -pending [69].

- Patent no. CN114474738A (China) “A mechanism and 3D printing system that reloads for 3D printer” filed on 17th January 2022, current status – pending [70].

- Patent no. CN216230793U – “Waste material wiping nozzle mechanism for 3D printer and 3D printer” filed 11th November 2021, granted 8th April 2022 [71].

3. Results

3.1. Case Study 1: Z Corp Patenting Thermoplastic Polymers for Powder Based 3D Printing

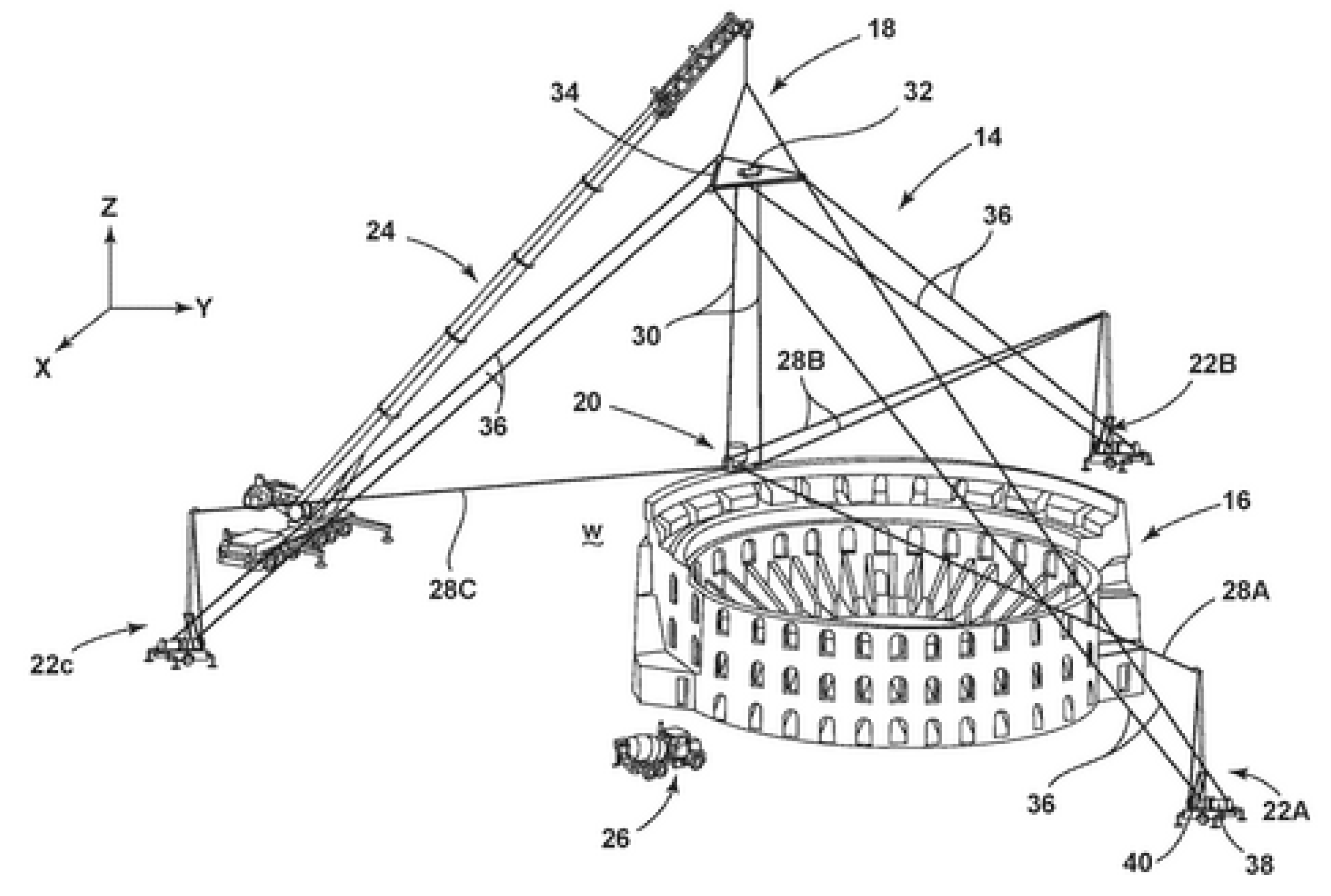

3.1. Case Study 2: Department of Energy Patenting the Open Source Hangprinter

3.3. Case Study 3: Comparing Patents Filed by BAMBU Lab to the Already Existing Open Source Technology

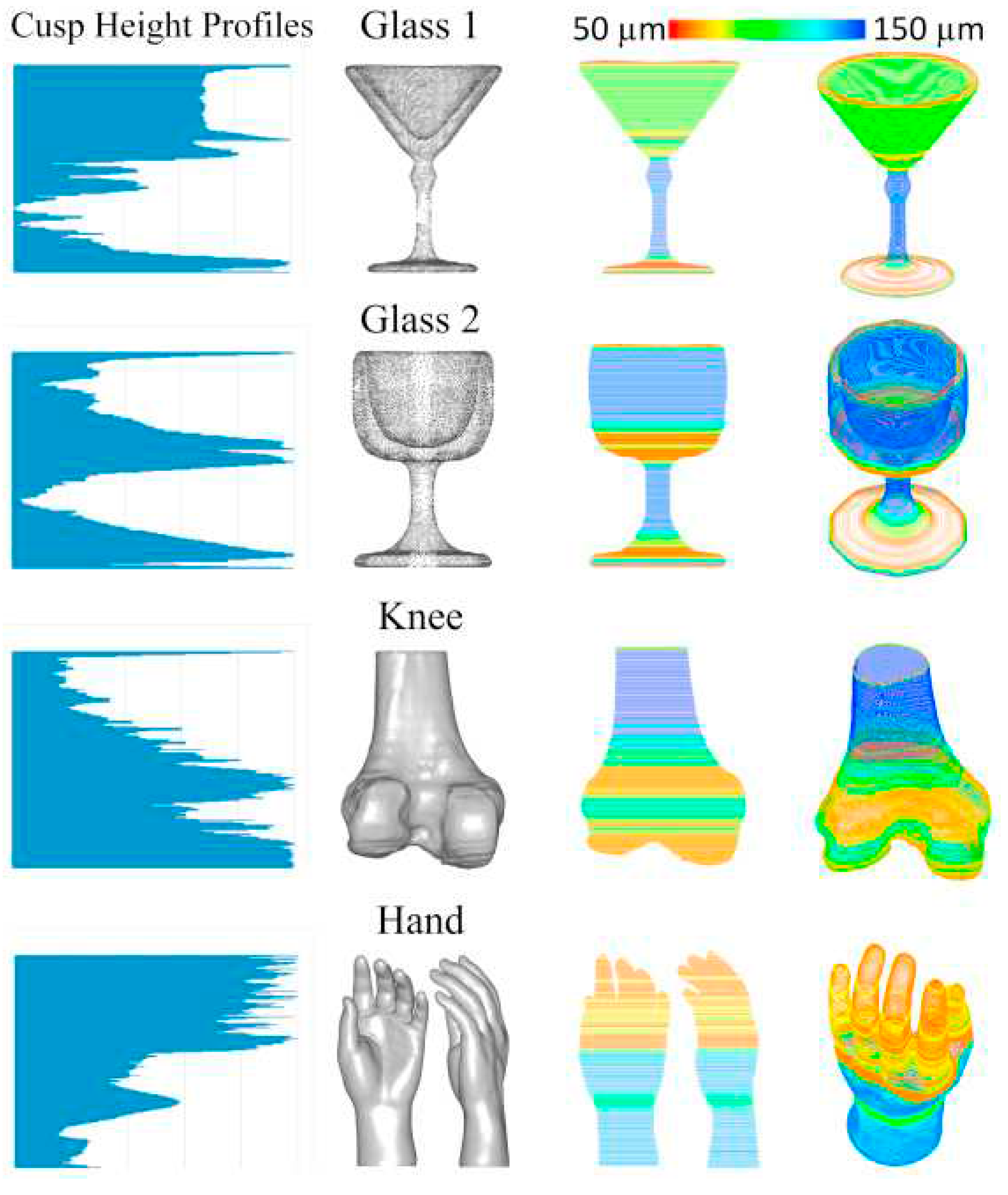

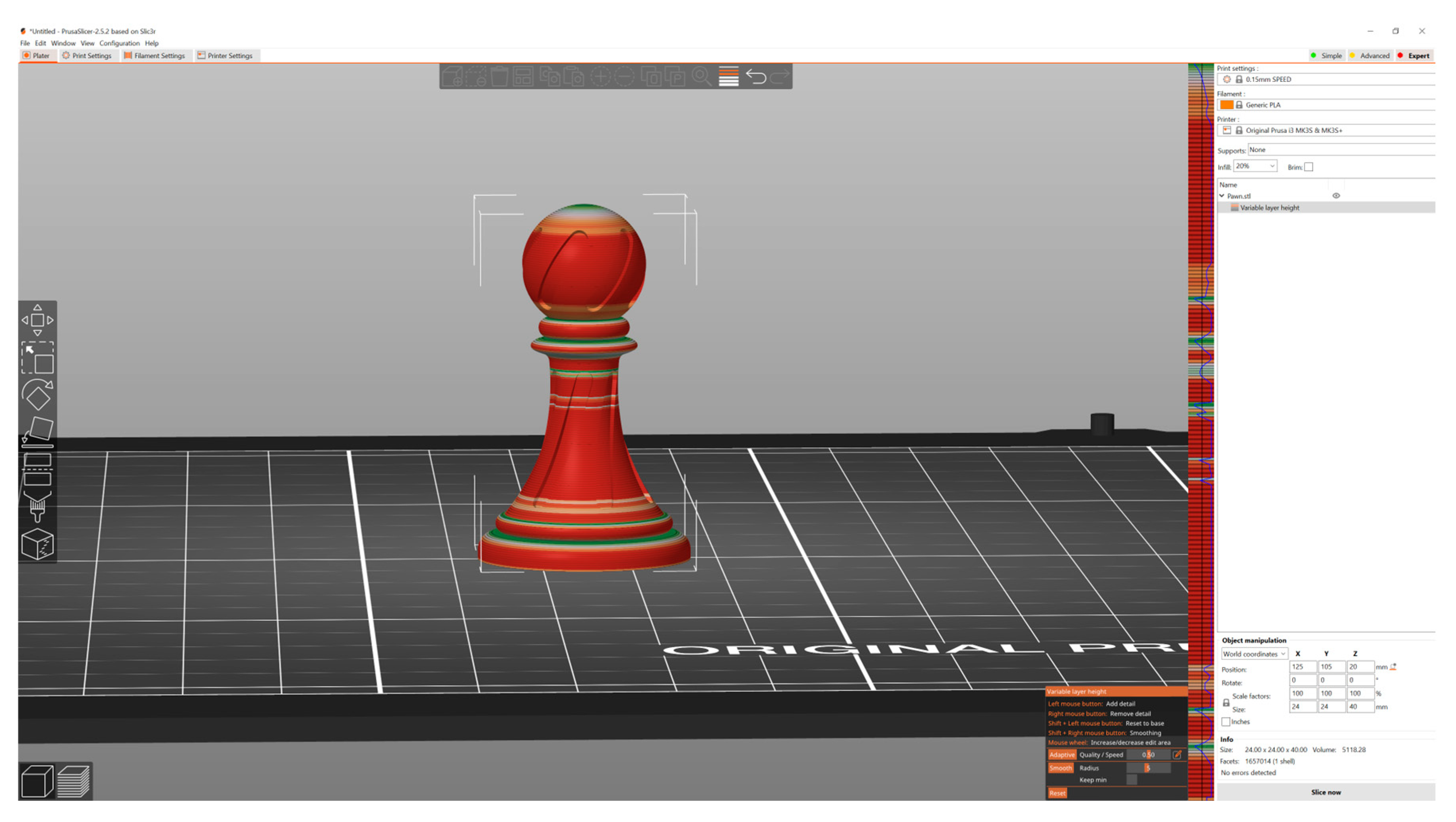

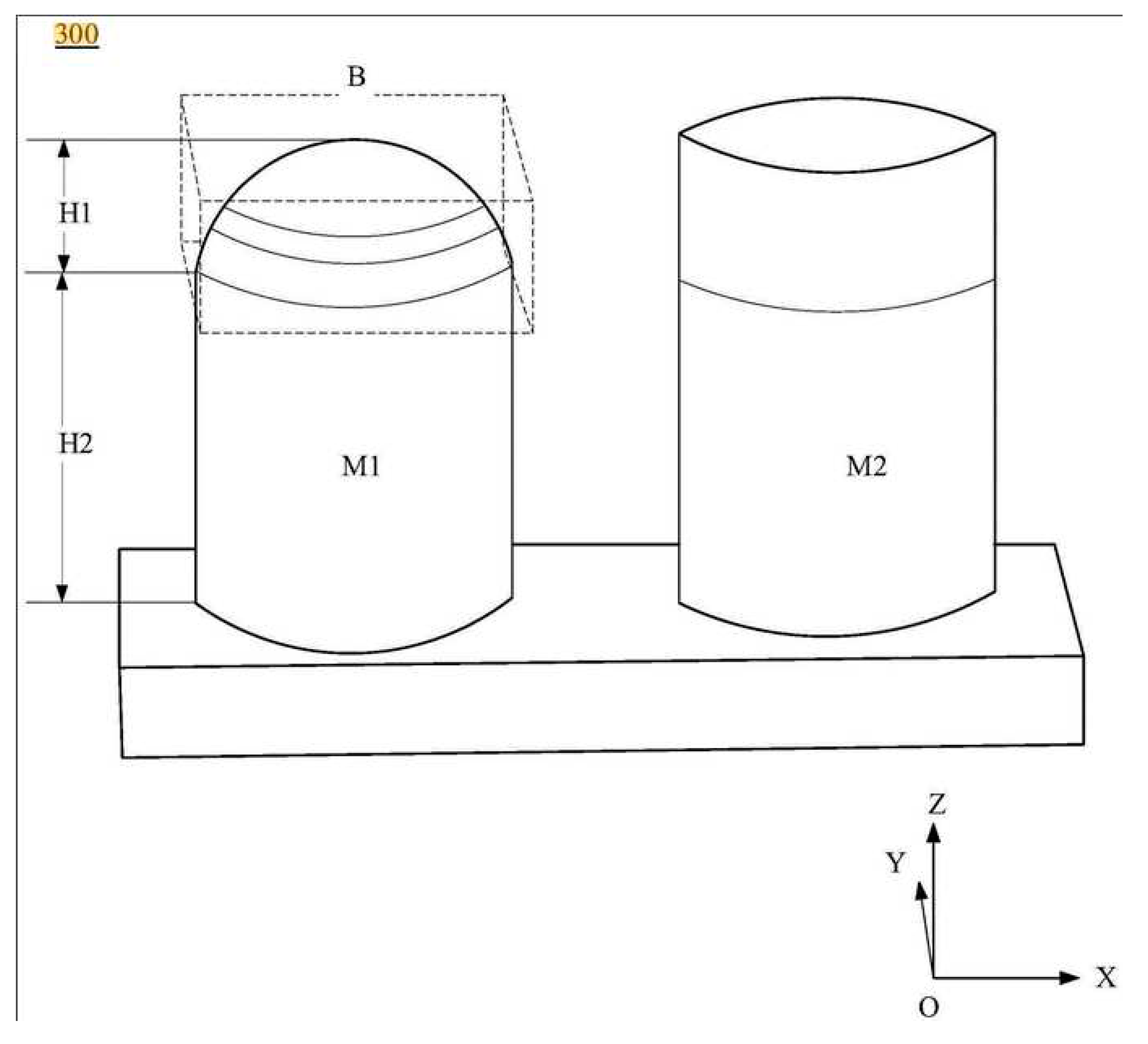

3.3.1. Patent no. CN114043726A – “Method and Apparatus for 3D Printing, Storage Medium, and Program Product”

3.3.2. Patent no. CN114474738A “A Mechanism and 3D Printing System That Reloads for 3D Printer.”

3.3.3. Patent no. CN216230793U – “Waste Material Wiping Nozzle Mechanism for 3D Printer and 3D Printer.”

4. Discussion

- Inhibiting innovation and slowing development: Patenting already existing open-source technology can hinder innovation by restricting the free flow of ideas and limiting the ability of others to build upon existing knowledge. It could stifle creativity and impede the collaborative nature of the vibrant innovative open-source community. This can hinder the pace of innovation and delay the benefits that open source 3-D printing can bring to various industries including in science [44,48,49,50,52,53,118,119], medical technology [120,121,122] and reaching sustainable development goals [123,124,125].

- Encouraging monopolies: Granting patents for already existing open-source technology could lead to the creation of IP monopolies [126,127], as companies with patents can control and exclude others from using or improving upon the technology. This can reduce competition, limit consumer choice, and drive-up prices all to the detriment of consumers (and in this case, prosumers).

- Patent thickets: If multiple companies use the patent parasite approach, the patenting of open-source technology could result in patent thickets, where numerous overlapping patents exist for the same or similar technologies. Patent thickets are well-known to create legal complexities, increase the risk of patent infringement lawsuits, and impede progress by making it difficult for innovators to navigate the patent landscape [128,129]. A well-known patent thicket [130] that has stifled a modern technology is found in nanotechnology [131,132], which has become so pernicious as to be called a modern “intellectual property tragedy” [133]. An obvious solution is to make nanotechnology open source for the betterment (and even greater commercial success) of that technological community [134], which provides all the more reason not to patent existing open-source technologies in the AM space.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Archibugi, D. Patenting as an Indicator of Technological Innovation: A Review. Science and Public Policy 1992, 19, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, B.B.; Park, W.G. The Influence of Patent Protection on Firm Innovation Investment in Manufacturing Industries. Journal of International Management 2007, 13, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresch, D.; Fink, M.; Harms, R. When Patents Matter: The Impact of Competition and Patent Age on the Performance Contribution of Intellectual Property Rights Protection. Technovation 2016, 57–58, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitch, E.W. The Nature and Function of the Patent System. The Journal of Law & Economics 1977, 20, 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, C.M. Managing the Provision of Knowledge: The Design of Intellectual Property Laws. In Providing Global Public Goods: Managing Globalization; Kaul, I., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2003; ISBN 978-0-19-515740-6. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, J.H. Patents and Antitrust: A Rethinking in Light of Patent Breadth and Sequential Innovation. Antitrust L.J. 1996, 65, 449–466. [Google Scholar]

- Takalo, T.; Kanniainen, V. Do Patents Slow down Technological Progress?: Real Options in Research, Patenting, and Market Introduction. International Journal of Industrial Organization 2000, 18, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.A.; Eisenberg, R.S. Can Patents Deter Innovation? The Anticommons in Biomedical Research. Science 1998, 280, 698–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, W. Innovation Needs Patents Reform. Research Policy 2001, 30, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, K.R. University Patenting and the Pace of Industrial Innovation. Industrial and Corporate Change 2007, 16, 505–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Lerner, J. Innovation and Its Discontents: How Our Broken Patent System Is Endangering Innovation and Progress, and What to Do About It; Princeton University Press, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4008-3734-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, C.; Eterovic, D. Do Patent Rights Matter? 40 Years of Innovation, Complexity and Productivity. World Development 2019, 115, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, K.R.; von Hippel, E. How Open Source Software Works: “Free” User-to-User Assistance. In Produktentwicklung mit virtuellen Communities: Kundenwünsche erfahren und Innovationen realisieren; Herstatt, C., Sander, J.G., Eds.; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, 2004; pp. 303–339. ISBN 978-3-322-84540-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlyn, D. Gift Economies in the Development of Open Source Software: Anthropological Reflections. Research Policy 2003, 32, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, E. The Cathedral and the Bazaar. Know Techn Pol 1999, 12, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehls, C.H. , Daniel Open Source Innovation: The Phenomenon, Participant’s Behaviour, Business Implications; Routledge: New York, 2015; ISBN 978-1-315-75448-2. [Google Scholar]

- Comino, S.; Manenti, F.M.; Parisi, M.L. From Planning to Mature: On the Success of Open Source Projects. Research Policy 2007, 36, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.T.; Kim, H.-W.; Gupta, S. Measuring Open Source Software Success. Omega 2009, 37, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S. The Success of Open Source; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-674-01858-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cloud Computing with Linux | Realise the True Potential & Value. Available online: https://www.rackspace.com/node/21235 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- How Linux Conquered the Fortune 500. Available online: https://fortune.com/2013/05/06/how-linux-conquered-the-fortune-500/ (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Supercomputers: All Linux, All the Time. Available online: https://www.zdnet.com/article/supercomputers-all-linux-all-the-time/ (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- IDC - Smartphone Market Share - Market Share. Available online: https://www.idc.com/promo/smartphone-market-share (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- IoT Developer Survey 2019. Available online: Https://Iot.Eclipse.Org/Community/Resources/Iot-Surveys/Assets/Iot-Developer-Survey-2019.Pdf (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Langenkamp, M.; Yue, D.N. How Open Source Machine Learning Software Shapes AI. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, July 27, 2022; pp. 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Gibney, E. Open-Source Language AI Challenges Big Tech’s Models. Nature 2022, 606, 850–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Five Ways That Open Source Software Shapes AI Policy. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/five-ways-that-open-source-software-shapes-ai-policy/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- TensorFlow - Google’s Latest Machine Learning System, Open Sourced for Everyone. Available online: https://ai.googleblog.com/2015/11/tensorflow-googles-latest-machine.html (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Mewald, C. The Golden Age of Open Source in AI Is Coming to an End. Available online: https://towardsdatascience.com/the-golden-age-of-open-source-in-ai-is-coming-to-an-end-7fd35a52b786 (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Milmo, D. Google Engineer Warns It Could Lose out to Open-Source Technology in AI Race. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/may/05/google-engineer-open-source-technology-ai-openai-chatgpt (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Gal, M.S. VIRAL OPEN SOURCE: COMPETITION VS. SYNERGY. Journal of Competition Law & Economics 2012, 8, 469–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberg, J.P.; Spaeth, S. Why Makers Make What They Make: Motivations to Contribute to Open Source Hardware Development. R&D Management 2020, 50, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A. Democratizing Production through Open Source Knowledge: From Open Software to Open Hardware. Media, Culture & Society 2012, 34, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaeth, S.; Hausberg, P. Can Open Source Hardware Disrupt Manufacturing Industries? The Role of Platforms and Trust in the Rise of 3D Printing. In The Decentralized and Networked Future of Value Creation: 3D Printing and its Implications for Society, Industry, and Sustainable Development; Ferdinand, J.-P., Petschow, U., Dickel, S., Eds.; Progress in IS; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 59–73. ISBN 978-3-319-31686-4. [Google Scholar]

- Definition (English). Available online: https://www.oshwa.org/definition/ (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Cern Ohl Version 2 · Wiki · Projects / CERN Open Hardware Licence Available online:. Available online: https://ohwr.org/project/cernohl/wikis/Documents/CERN-OHL-version-2 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Gibb, A. Building Open Source Hardware: DIY Manufacturing for Hackers and Makers; Pearson Education, 2014; ISBN 978-0-13-337390-5. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, M.C.; Forsslund, J. Spurring Innovation in Spatial Haptics: How Open-Source Hardware Can Turn Creativity Loose. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine 2017, 24, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosemagen, S.; Liboiron, M.; Molloy, J. Gathering for Open Science Hardware 2016. 2017, 1, 4. [CrossRef]

- Hsing, P.-Y. Sustainable Innovation for Open Hardware and Open Science – Lessons from The Hardware Hacker. 2018, 2, 4. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Sponsored Libre Research Agreements to Create Free and Open Source Software and Hardware. Inventions 2018, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, P. Tools for Public Participation in Science: Design and Dissemination of Open-Science Hardware. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Creativity and Cognition; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, June 13 , 2019; pp. 697–701. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M. Quantifying the Value of Open Source Hard-Ware Development. Modern Economy 2015, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.K.; Gould, P.J. Open-Source Hardware Is a Low-Cost Alternative for Scientific Instrumentation and Research. Modern Instrumentation 2012, 1, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberloier, S.; Pearce, J.M. Open Source Low-Cost Power Monitoring System. HardwareX 2018, 4, e00044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C. Build It. Share It. Profit. Can Open Source Hardware Work? | WIRED. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2008/10/ff-openmanufacturing/ (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Pearce, J.M. Economic Savings for Scientific Free and Open Source Technology: A Review. HardwareX 2020, 8, e00139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnett, C. Open Source Hardware for Instrumentation and Measurement. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 2011, 14, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Building Research Equipment with Free, Open-Source Hardware. Science 2012, 337, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Costs; Elsevier, 2013; ISBN 978-0-12-410486-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, A.M. Haves and Have Nots Must Find a Better Way: The Case for Open Scientific Hardware. PLOS Biology 2018, 16, e3000014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E. ‘Open-Hardware’ Pioneers Push for Low-Cost Lab Kit. Nature 2016, 531, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Cut Costs with Open-Source Hardware. Nature 2014, 505, 618–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittbrodt, B.T.; Glover, A.G.; Laureto, J.; Anzalone, G.C.; Oppliger, D.; Irwin, J.L.; Pearce, J.M. Life-Cycle Economic Analysis of Distributed Manufacturing with Open-Source 3-D Printers. Mechatronics 2013, 23, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.E.; Pearce, J. Emergence of Home Manufacturing in the Developed World: Return on Investment for Open-Source 3-D Printers. Technologies 2017, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, G. A Revolution in the Making; Affirm Press, 2014; ISBN 978-1-922213-30-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sells, E.; Bailard, S.; Smith, Z.; Bowyer, A.; Olliver, V. RepRap: The Replicating Rapid Prototyper: Maximizing Customizability by Breeding the Means of Production. In Handbook of Research in Mass Customization and Personalization; World Scientific Publishing Company, 2009; pp. 568–580. ISBN 978-981-4280-25-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Haufe, P.; Sells, E.; Iravani, P.; Olliver, V.; Palmer, C.; Bowyer, A. RepRap – the Replicating Rapid Prototyper. Robotica 2011, 29, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kentzer, J.; Koch, B.; Thiim, M.; Jones, R.W.; Villumsen, E. An Open Source Hardware-Based Mechatronics Project: The Replicating Rapid 3-D Printer. In Proceedings of the 2011 4th International Conference on Mechatronics (ICOM); May 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer, A. 3D Printing and Humanity’s First Imperfect Replicator. 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing 2014, 1, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Qian, J.-Y. Economic Impact of DIY Home Manufacturing of Consumer Products with Low-Cost 3D Printing from Free and Open Source Designs. European Journal of Social Impact and Circular Economy 2022, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home. Available online: https://makezine.com/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Průša, J. The State of Open-Source in 3D Printing in 2023. Available online: https://blog.prusa3d.com/the-state-of-open-source-in-3d-printing-in-2023_76659/ (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Bredt, J.F.; Clark, S.L.; Williams, D.X.; DiCologero, M.J. Thermoplastic Powder Material System for Appearance Models from 3D Printing Systems; Google Patents 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bredt, J.F.; Clark, S.L.; Williams, D.X.; Dicologero, M.J. Thermoplastic Powder Material System for Appearance Models from 3d Printing Systems 2011.

- Post, B.K.; Love, L.J.; Lind, R.F.; CHESSER, P.C.; Roschli, A.C. Cable-Driven Additive Manufacturing System 2022.

- Ludvigsen, T. Hangprinter. Available online: https://hangprinter.org (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Patent Search for “Shenzhen Tuozhu Technology Co Ltd”. (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- 魏亮辉 用于3d打印的方法及装置、存储介质和程序产品, Shenzhen Tuozhu Technology Co ltd, China. CN114043726A, 15 February 2022.

- 田开望 用于3d打印机的换料机构及3d打印系统, Shenzhen Tuozhu Technology Co ltd, China. CN114474738A, 13 May 2022.

- 张泽政 用于3d打印机的废料擦嘴机构及3d打印机, Shenzhen Tuozhu Technology Co ltd, China. CN216230793U, 8 April 2022.

- PLA for 3D Printing: All You Need to Know - 3Dnatives. Available online: https://www.3dnatives.com/en/pla-3d-printing-guide-190820194/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Pearce, J.M. A Novel Approach to Obviousness: An Algorithm for Identifying Prior Art Concerning 3-D Printing Materials. World Patent Information 2015, 42, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choppara, D.; Garmulewicz, A.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source 3-D Printing Materials Database Generator. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B. US Court Rules, Once Again, That AI Software Can’t Be Listed as Inventor on a Patent. Available online: https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/10/us-court-rules-once-again-that-ai-software-cant-hold-a-patent/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Ludvigsen, T. Prior Art Relevant to Patent US 11230032. Available online: https://torbjornludvigsen.com/blog/2022 (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Stevenson, K. The Hangprinter: A Frameless 3D Printer « Fabbaloo. Available online: https://www.fabbaloo.com/2017/03/the-hangprinter-a-frameless-3d-printer (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Jackson, B. Interview with the Inventor of the Frameless Hangprinter 3D Printer Building the Tower of Babel. Available online: https://3dprintingindustry.com/news/interview-inventor-frameless-hangprinter-3d-printer-building-tower-babel-107749/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- 3D Printing Outside the Box: The Hangprinter Prints in Midair Without Any Limits | 3DPrint.Com | The Voice of 3D Printing / Additive Manufacturing. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20170520051008/https://3dprint.com/167250/hangprinter-midair-3d-printer/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Watkin, H. The Open Source Hangprinter Prints Without A Frame. Available online: https://all3dp.com/open-source-hangprinter-prints-without-frame/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- S, R. Der Hangprinter druckt ohne Rahmen und Gehäuse. Available online: https://www.3dnatives.com/de/hangprinter-3d-drucker-1003171/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Umea University Develops Low-Cost, Flexible 3D Printer. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/866985/umea-university-develops-low-cost-flexible-3d-printer (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Torbjørns Reprap Blog. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180304164205/http://vitana.se:80/opr3d/tbear/2017.html#hangprinter_project_33 (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Hangprinter, Wikipedia Article. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hangprinter&oldid=1149691634 (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Frameless “Hangprinter” RepRap Turns an Entire Room into a 3D Printer. Available online: http://www.3ders.org/articles/20170308-frameless-hangprinter-reprap-turns-an-entire-room-into-a-3d-printer.html (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Hangprinter - RepRap Project | Oslo Hackathon - Progress | Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/groups/hangprinter/posts/195485447628289/ (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Resources, M. MPEP. Available online: https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/s2141.html (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Mao, H.; Kwok, T.-H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.C.L. Adaptive Slicing Based on Efficient Profile Analysis. Computer-Aided Design 2019, 107, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PrusaSlicer | Original Prusa 3D Printers Directly from Josef Prusa. Available online: https://www.prusa3d.com/page/prusaslicer_424/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- The SMuFF. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/the-smuff (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Takahashi, H.; Punpongsanon, P.; Kim, J. Programmable Filament: Printed Filaments for Multi-Material 3D Printing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; ACM: Virtual Event USA, October 20, 2020; pp. 1209–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Retractable Purge Mechanism – BigBrain3D. Available online: https://www.bigbrain3d.com/product/retractable-purge-mechanism/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Jubilee. Available online: https://jubilee3d.com/index.php?title=Main_Page (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Průša, J. Multi Material Upgrade 2.0 Is Here! Available online: https://blog.prusa3d.com/multi-material-upgrade-2-0-is-here_8700/ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Prusa 3D by Josef Prusa How Does the Multi Material Upgrade 2.0 Work? Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E1ZxTCApLrs (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Design Prototype Test Wire Brush, vs. Silicone Wiper - Which Is Best for Auto Nozzle Cleaning? Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PGaVSiPU9n0 (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Design Prototype Test Custom Nozzle Wiper for Ender3 & CR10 - No More Layer Shifting PETG! Available online:. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhiDD0E_Fjg (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- René Jurack Automatic Hotend Nozzle Cleaner / Brush. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fbTuwtfOJpQ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Ruvim Kub. Lifting Gear For Automatic Nozzle Cleaner - Автo Очистка Сoпла Для 3Д Принтера. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrOSXlZ6W1k (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- Thingiverse.com Lifting Gear For Automatic Nozzle Cleaner by Ruvimkub. Available online: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:4265679 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Core3D 3D Printer Circular Nozzle Cleaner. Available online: https://www.instructables.com/3D-Printer-Circular-Nozzle-Cleaner/ (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- LulzBot | Taz-6-Product-Page. Available online: https://lulzbot.com/store/taz-6 (accessed on 24 July 2023).

- 刘浩 用于存储3d打印线材的料盘, Shenzhen Tuozhu Technology Co ltd, China. CN216267657U, 12 April 2022.

- Thingiverse.com 1kg Masterspool Concept by 3DTomorrow. Available online: https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:3994146 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- 黄宏升; 陈子寒 3d打印机和用于3d打印机的方法 2022.

- Fuzzy Skin | Prusa Knowledge Base. Available online: https://help.prusa3d.com/article/fuzzy-skin_246186 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- 陈子寒; 黄宏升; 曹瑾玮 用于3d打印的打印平台及3d打印机 2022.

- Petsiuk, A.L.; Pearce, J.M. Open Source Computer Vision-Based Layer-Wise 3D Printing Analysis. Additive Manufacturing 2020, 36, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 华明进 一种智能3d打印平台, Harbin Kuncheng Technology Co Ltd.: China. CN111775448A, 16 October 2020.

- Jaydeep 3D Printer Polar 3D. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZXjlcSOUoA (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- 陈鹏 3d打印机, Shenzhen Tuozhu Technology Co ltd, China. CN216182842U, 5 April 2022.

- Creality Creality 3D PAD Upgraded Touch Screen For All FDM 3D Printers. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qR7PkQ0IJs0 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- CDC - Parasites - About Parasites. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/about.html (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Patent Trolls as Parasites. Available online: https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2014/04/patent-trolls-as-parasites/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- DiBona, C.; Ockman, S. Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution; O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1999; ISBN 978-0-596-55390-6. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen, I.T.S.; Savin, H.; Partanen, J.; Seppälä, J.; Pearce, J.M. Towards National Policy for Open Source Hardware Research: The Case of Finland. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 155, 119986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Let the Arms Race Begin. Available online: https://blog.bambulab.com/let-the-arms-race-begin/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Coakley, M.; Hurt, D.E. 3D Printing in the Laboratory: Maximize Time and Funds with Customized and Open-Source Labware. J Lab Autom. 2016, 21, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Economic Savings for Scientific Free and Open Source Technology: A Review. HardwareX 2020, 8, e00139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. Medical Applications for 3D Printing: Current and Projected Uses. P T 2014, 39, 704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M. Distributed Manufacturing of Open Source Medical Hardware for Pandemics. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2020, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.; Akmal, J.S.; Pei, E.; Wolff, J.; Jaribion, A.; Khajavi, S.H. 3D Printing in COVID-19: Productivity Estimation of the Most Promising Open Source Solutions in Emergency Situations. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M.; Blair, C.M.; Laciak, K.J.; Andrews, R.; Nosrat, A.; Zelenika-Zovko, I. 3-D Printing of Open Source Appropriate Technologies for Self-Directed Sustainable Development. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2010, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancio, J.; Morales Tirado, M.; Pearce, J. Equitable Research Capacity Towards the Sustainable Development Goals: The Case for Open Science Hardware. JSPG 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldona, E.B.; Dizon, J.R.C.; Espera, A.H.Jr.; Advincula, R.C. On the Economic, Environmental, and Sustainability Aspects of 3D Printing toward a Cyclic Economy. In Energy Transition: Climate Action and Circularity; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society, 2022; Volume 1412, pp. 507–525. ISBN 978-0-8412-9796-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boldrin, M.; Levine, D.K. Against Intellectual Monopoly; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008; ISBN 978-0-521-87928-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, U. The Crisis of Intellectual Monopoly Capitalism. Cambridge Journal of Economics 2014, 38, 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, G.; DeKORTE, D. The Problem of Patent Thickets in Convergent Technologies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2006, 1093, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Graevenitz, G.; Wagner, S.; Harhoff, D. Incidence and Growth of Patent Thickets: The Impact of Technological Opportunities and Complexity. The Journal of Industrial Economics 2013, 61, 521–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, J.P. Written Description Requirement in Nanotechnology: Clearing a Patent Thicket. J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 2006, 88, 489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Lemley, M.A. Patenting Nanotechnology. Stan. L. Rev. 2005, 58, 601–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makker, A. The Nanotechnology Patent Thicket and the Path to Commercialization Note. S. Cal. L. Rev. 2010, 84, 1163–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Nanotechnology: Solutions to a Modern Intellectual Property Tragedy. Nano Today 2013, 8, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Make Nanotechnology Research Open-Source. Nature 2012, 491, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSHWA Certification. Available online: https://certification.oshwa.org/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Peplinski, J.; Velis, E.; Pearce, J.M. Towards Open Source Patents: Semi-Automated Open Hardware Certification from MediaWiki Websites. World Patent Information 2022, 71, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).