Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction. Targets

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology & Data Set

4. Results & Discussions

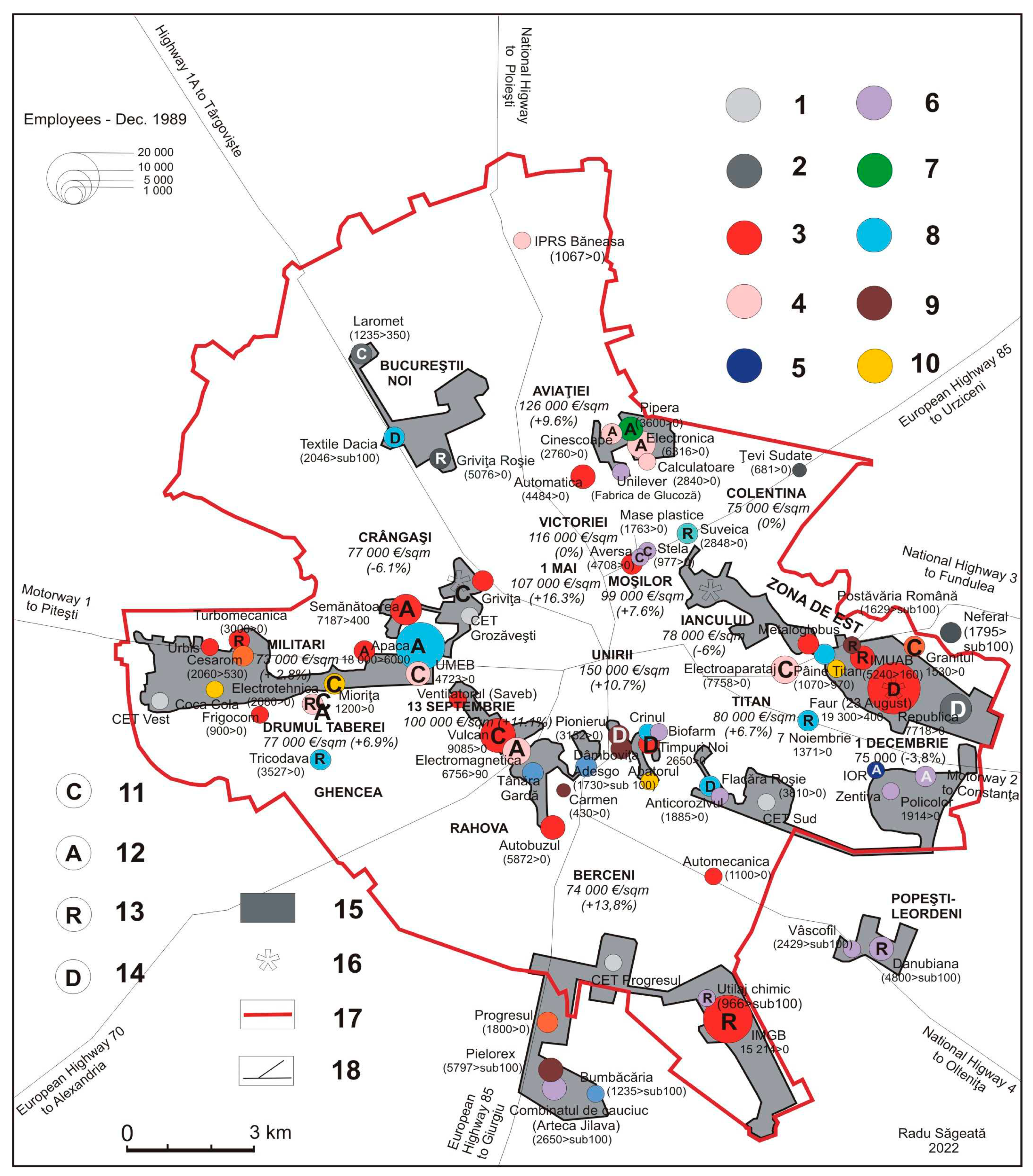

4.1. Industrialization and Urbanization in Central and Eastern Europe 1

4.2. Deindustrialization and tertiarization. The suburbanization of large cities in Romania

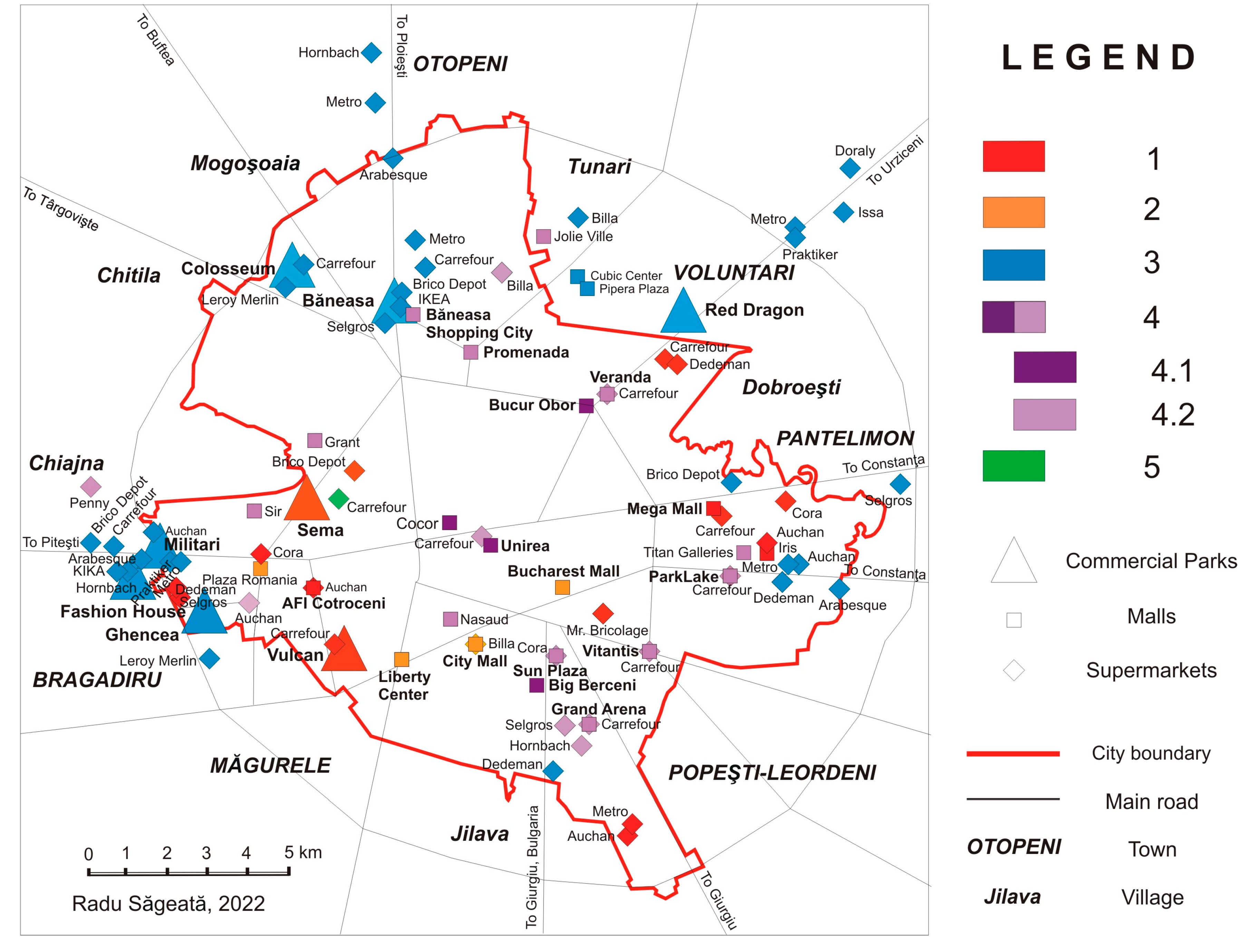

4.3. Case-study : Deindustrialization and tertiarization through commercial investments. Changes in urban space organization.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sassen, S. The global city, Princeton University Press, New York – London – Tokyo – Princeton - Oxford, 2001.

- Musterd, S.; Marcińzak, S.; van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich, Urban Geography, 38(7), 2017, 1062-1083. [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S. Creţan R., Ianăş A., Satmari A., The Romanian post-socialist city: urban renewal and gentrification, West University Publishing House, Timișoara, 2009.

- Van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. New perspectives on ethnic segregation over time and space. A domains approach. Urban Geography, 37(7), 2016, 953-962. [CrossRef]

- Jucu I-S., Urban identities in music geographies: A continental-scale approach, Territorial Identity and Development, 3(2), 2018, 5-29. [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.-P., Jr. Towards a typology of urban-rural relationships, The Professional Geographer, 23(4), 1971, 319-323. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy S-M., Urban policy mobilities, argumentation and the case of the model city, Urban Geography, 37 (1), 2016, 96-116. [CrossRef]

- Stead, D. , de Vries J., Tasan-Kok T., Planning cultures and histories: Influences on the evolution of planning system and spatial development patterns, European Planning Studies 23(11), 2015, 2127-2132. [CrossRef]

- Burgess E-W., The Growth of the city. An Introduction to a Research Project, In The trends of population. Publication of the American Sociological Society, XVIII, 1925, pp. 85-97 and In Urban Ecology. An International Perspective on the Interaction Between Humans and Nature, Springer, 2008, pp. 71-78.

- Hoyt, H. One hundred years of land values in Chicago, Beard Books & Franklin Classics, Chicago, 2000 & 2018.

- Harris Ch, Ullman E-D., The nature of the cities, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 242(1), 1945. [CrossRef]

- Mihăilescu, V. Bucureştii din punct de vedere antropogeografic şi etnografic [Bucharest, considered from the antropo- geographical and etnographical point of view], Anuarul de Geografie şi Antropogeografie, 4, 1915, 145-226.

- Mihăilescu, V. , Oraşul ca fenomen antropogeografic [The town as an antropogeographical phenomenon], Cercetări şi studii geografiece, I, 1937-1938, 29-41.

- Rădulescu N-Al., Zonele de aprovizionare ale câtorva oraşe din sudul României [Supply areas of several cities in southern Romania], Revista geografică, I, 1944, 1-3.

- Garnier J-B., Chabot G., Traité de géographie urbaine [Treaty of urban geography], Librairie Armand Colin, Paris, 1963.

- Alonso, W. , Location and land use. Toward a general theory of land rent, Harvard University Press, Harvard, 1964.

- Dickinson R-E., City and Region. A geographic interpretation, Routledge, London, 1964.

- Mayer M-H., Koln, C-F., Readings in Urban Geography, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1964.

- Choley R-J., Haggett P. (Eds.), Models in Geography, Methuen, London, 1967.

- Badcock B-A., A preliminary note on the study of intra-urban physiognomy, The Professional Geographer, 22(4), 1970, 189-196. [CrossRef]

- Abler, R. , Adams J., Gould P., Spatial organization, Prentice Hall, London, 1972.

- Soppelsa, J. , Des distorsionsrécentes de la théorie des lieuxcentraux. Propositions pour une nouvelle approche de la notion de hiérarchieurbaine [Recent distorsions of central place theory. Proposal for a new deepening of the notion of urban hierarchy], Bulletin de l’Association des GéographesFrançais, 439-440, 1977, 13-19.

- Bastié, J. , Dézert B., L’espace urbain [Urban space], Masson, Paris - New York – Barcelona - Milano, 1980.

- Cucu, V. , Oraşele României [The cities of Romania], Scientific Publishing House, Bucharest, 1970.

- Iordan, I. Zona periurbană a Bucureştilor [The periurban area of Bucharest], Romanian Academy Publishing House, Bucharest, 1973.

- Ungureanu, A. , Oraşele din Moldova. Studiu de geografie economică [Towns in Moldavia. Study of economic geography], Romanian Academy Publishing House, Bucharest, 1980.

- Ronnais, P. , Urbanization in Romania. A geography of social and economic change since Independence, The Economic Research Institute, Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm, 1983.

- Ianoş I., Oraşele şi organizarea spaţiului geografic. Studiu de geografie economic asuprat eritoriului României [Towns and the organization of the geographical space. Studies of economic geography on Romania’s territory], Romanian Academy Publishing House, Bucharest, 1987.

- Nelson A-C., Dueker K-J., The exurbanization of America and its planning policy implications, Journal of Planning Education and Research, 9, 1990, 91-100. [CrossRef]

- Esparza A-X., Exurbanization and Aldo Leopold’s human-land community, In Esparza A-X. & McPherson G. (Eds), The planner’s guide to natural resource conservation, Springer, New York, 2009, pp. 3-26. [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, I. , Modificările mediului în aria metropolitană a Municipiului București [Environmental changes in the metropolitan area of the City of Bucharest], Romanian Academy Publishing House, Bucharest, 2010.

- Zasada I., Fetner Ch., Piorr A., Nielsen-Thomas S., Peri-urbanization and multifunctional adaptation of agriculture around Copenhagen, Danish Journal of Geography, 111(1), 2011, 59-72. [CrossRef]

- Gospodini, A. , Urban morphology and place identity in European cities: Built heritage and Innovative design, Journal of Urban Design, 9(2), 2004, 225-248.

- Gauthier, G. Gilliland J., Mapping urban morphology: a classification scheme for interpreting contributions to the study of urban form, Urban Morphology, 10(1), 2006, 41-50.

- Warf, B. Global cities, cosmopolitanism and geographies of tolerance, Urban Geography, 36(6), 2015, 927-946. [CrossRef]

- Knieling J., Othengrafen F., Planning Culture – A Concept to Explain the Evolution of Planning Policies and Processes in Europe ?, European Planning Studies, 23(11), 2015, 2133-2147. [CrossRef]

- Bezin E., Moizeau F., Cultural dynamics, social mobility and urban segregation. Journal of Urban Economics, 99, 2017, 173-187. [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. , The study of the landscape physiognomy of urban areas - the methodology development, Methods of Landscape Research, Dissertations Commission of Cultural Landscape, 8, 2008, 74-85.

- Koter, M. Kulesza M., The study of urban form in Poland, Urban Morphology, 14(2), 2010, 111-120.

- Kauffmann, A. Is the “Central german metropolitan region” spatially integrated? An Empirical assessment of commuting relations, Urban Studies, 53(9), 2015, 1853-1868. [CrossRef]

- Neacşu M.-C., Oraşul sub lupă. Concepte urbane. Abordare geografică [The city under the magnifying glass. Urban concepts. Geographic approach], Pro-Universitaria Publishing House, Bucharest, 2010.

- Storper, M.; Scott, A.-J. Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment, Urban Studies, 53(6), 2016, 1114-1136. [CrossRef]

- Fenster, T. Creative destruction in urban planning procedures: the language of “renewal” and “exploitation”, Urban Geography, 40(1), 2019, 37-57. [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, I. Sisteme teritoriale. O abordare geografică [Territorial systems. A geographical approach], Technic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2000.

- Ianoş, I. Dinamica urbană. Aplicaţii la oraşul şi sistemul urban românesc [Urban dynamics. Applications on the City and the Romanian Urban System], Technic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2004.

- Ianoş, I. , Heller W., Spaţiu, economie şi sisteme de aşezări [Space, Economy and Settlements Systems], Technic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

- Tălângă, C. , Transporturile şi sistemele de aşezări din România [Transportation and the settlement systems in Romania], Technic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2000.

- Groza O., Les territoires de l’industrie [The territories of the industry], Didactic & Pedagogical Publishing House, Bucharest, 2003.

- Popescu C., Industria românească în secolul XX. Analiză geografică [Romanian industry in the 20th century. A geographical analysis], Oscar Print Publishing House, Bucharest, 2000.

- Nica-Guran L., Investiţii străine directe. Dezvoltarea sistemului de aşezări din România [Foreign direct investments and the development of the settlements in Romania], Technic Publishing House, Bucharest, 2002.

- Dumitrescu B., Oraşele monoindustriale din România între industrializare forţată şi declin economic, [One-industry town in Romania between forced industrialization and economic decline], University Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008.

- Mocanu I., Şomajul din România. Dinamică şi diferenţieri geografice [Unemployment in Romania. Dynamics and geographical differentiation], University Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008.

- Cepoiu A-L., Rolul activităților industriale în dezvoltarea așezărilor din spațiul metropolitan al Bucureștilor [The role of industrial activities in the development of settlements in the metropolitan area of Bucharest], University Publishing House, Bucharest, 2009.

- Chelcea L., Bucureştiul postindustrial. Memorie, dezindustrializare şi regenerare urbană [Post-industrial Bucharest. Memory, deindustrialization and urban regeneration], Polirom Publishing House, Iași, 2008.

- Neacşu M-C., Imaginea urbană, element esenţial în organizarea spaţiului [The urban image, an essential element in the organization of the space], Pro-Universitaria Publishing House, Bucharest, 2010.

- Gavriş, A. Mari habitate urbane în Bucureşti [Large urban habitats in Bucharest-City], University Publishing House, Bucharest, 2011.

- Mionel V., Segregarea urbană. Separaţi dar împreună [Urban segregation. Separate but together], University Publishing House, Bucharest, 2012.

- Nae, M. Geografia calităţii vieţii urbane. Metode de analiză [Geography of urban quality of life. Methods of analysis], University Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

- Săgeată, R. Fluctuating geographical position within geopolitical and historical context. Case Study: Romania, Geographica Pannonica, 24(1), 2020, 25-41. [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R. Structurile urbane de tip socialist – o individualitategeografică ? [Socialist urban structures - a geographical individuality ?], Analele Universităţii din Oradea, Geografie, XII, 2003, 61-69.

- Fourcher, M. Fragments d’Europe. Atlas de l’Europe médiane et orientale [Fragments of Europe. Atlas of Middle and Eastern Europe], Fayard, Paris, 1993.

- Jigorea-Oprea, L., Popa N. Industrial brownfields: An unsolved problem in post-socialist cities. A comparison between two mono industrial cities: Reşiţa (Romania) and Pančevo (Serbia), Urban Studies, 54(12), 2016, 2719-2738. [CrossRef]

- Săgeată R., Politics and its Impact on the Urban Physiognomy in Central and Eastern Europe: A Case Study of Bucharest, Central European Journal of Geography and Sustainable Development, I(1), 2019, 25-39.

- Lever W-F., Deindustrialization and the reality of the post-industrial city, Urban Studies, 28(6), 1991, 983-999. [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, H. Gosnell H., Abrams J., Amenity migration: diverse conceptualization of drives, socioeconomic dimensions, and emerging challenges, Geojournal, 76, 2011, 303-322. [CrossRef]

- Giurescu C-C., Istoria Bucureştilor [The history of Bucharest], III-ed, Vremea Publishing House, Bucharest, 2009.

- Nicolae I., Suburbanismul, ca fenomen geografic în România [Suburbanism, as a geographical phenomenon in Romania], Meronia Publishing House, Bucharest, 2002.

- Săgeată, R. Commercial services and urban space reconversion in Romania (1990-2007), Acta Geographica Slovenica, 60(1), 2020, 49-60. [CrossRef]

- NAI Romania, Piaţa spaţiilor comerciale. Studiu de piaţă imobiliară 2014. Tendinţe 2015 [The Market of Commercial Areas. A Housing-Market Study 2014. Trends 2015], Bucharest. http//www.nairomania.ro/images/publicatii/doc_34_53.pdf, 2014. (Acc. July, 2017).

- Isărescu, M. Opening Address at the scientific gathering on “Romania in the European Union”, organized by the Romanian Academy], 2017. http://www.storage.dns.mpinteractiv.ro/media/pdf (Acc. July, 2019).

- Mirea D-A., Industrial landscape – a landscape in transition in the Municipality Area of Bucharest. Geographical Phorum – Geographical Studies and Environment Protection Research, X(2), 2011, 295-302. [CrossRef]

- Cushman & Wakefield, România pe ultimul loc în Europa la densitatea de spaţiicomerciale [Romania at the bottom of commercial area density in Europe], DC News, Bucharest, 2017.

- Grigorescu, I., Kucsicsa G., Mitrică B., Assessing spatio-temporal dynamics of urban sprawl in the Bucharest Metropolitan Area over the last century, Land Use/Cover Changes in Selected Regions in the World, X, International Geographical Union, Charles University, Prague, 2015, 19-27.

| City | The evolution of urban area (hectars) | Demographic evolution (inhabitants) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2021 | 2011-2021 | 2011 | 2021 | 2011-2021 | |

| Bucharest | 16 150 | 24 190 | + 8 040 | 1 883 425 | 1 716 983 | - 166 442 |

| Cluj-Napoca | 9 232 | 10 472 | + 1 240 | 324 576 | 286 598 | - 37 978 |

| Iaşi | 6 213 | 6 924 | + 711 | 290 422 | 271 692 | - 18 730 |

| Constanţa | 6 000 | 6 042 | + 42 | 283 872 | 263 707 | - 20 165 |

| Timişoara | 6 870 | 7 600 | + 730 | 319 279 | 250 849 | 68 430 |

| Braşov | 11 056 | 11 056 | 0 | 253 200 | 237 589 | 15 611 |

| Craiova | 7 043 | 7 063 | + 20 | 269 506 | 234 140 | 35 366 |

| Galaţi | 4 546 | 6 452 | + 1 906 | 249 432 | 217 851 | 31 581 |

| Oradea | 7 719 | 8 182 | + 463 | 196 367 | 183 105 | 13 262 |

| Ploieşti | 5 190 | 5 412 | + 222 | 196 367 | 183 105 | 13 262 |

| 1 | We include in Central and Eastern Europe the geopolitical ensemble composed of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Russia (the Kaliningrad region), Belarus, Ukraine, The Republic of Moldova and Romania [59]. |

| 2 | Here, the construction of the apartment buildings started in 1962, as a response to the construction of the industrial platform to the West of the Romanian Capital. |

| 3 | The Law on the approval of the National Territory Improvement Plan no. 351 of July 6, 2001. Section IV: The Network of localities, Official Monitor, XIII, 408 of July 24, 2001 |

| 4 | The majority of production units were grouped into five industrial platforms |

| 5 | In the case of Râmnicu Vâlcea municipality, urban population density has fallen from 5 567,1 inhabitants/km2 in 2007 to 2 432,1 inhabitants/km2 in 2017. |

| 6 | From 21,537,563 inhabitants to 19,644,350 inhabitants, from 11,877,695 inhabitants, respectively to 10,531,255 respectively (data for the interval July 1st 2007 and July 1st 2017). For the same interval, the degree of urbanization dropped from 55.1% to 53.6%. Source: Romanian Statistical Yearbooks 2008 and 2018, National Institute of Statistics, Bucharest. |

| 7 | These accounted for almost half (49.5%) of Romania's urban population |

| 8 | In many cases, cooperation between urban municipalities and those of suburban communes is lacking, despite their integration into homogeneous territorial structures such as metropolitan areas. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).