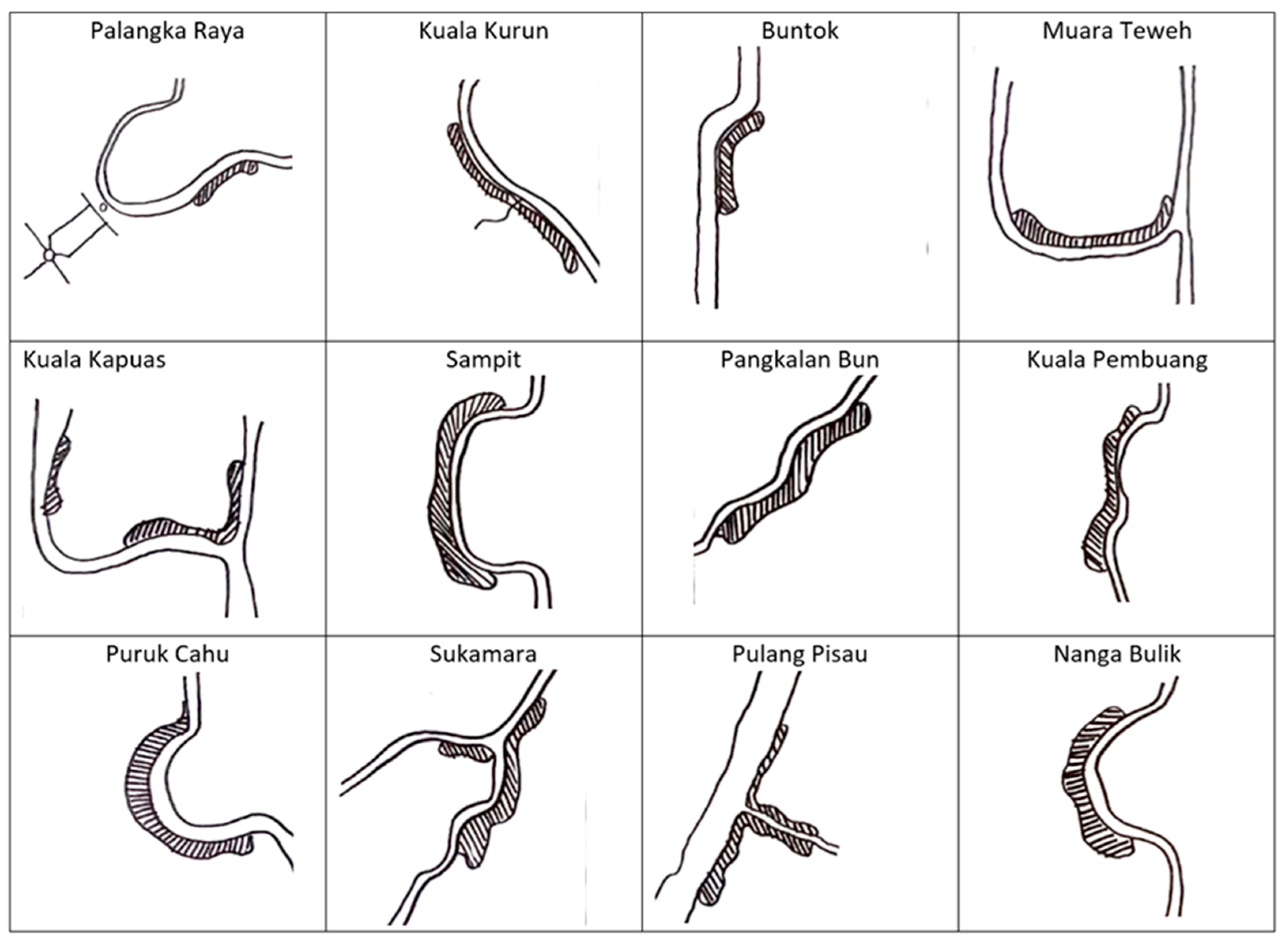

3.1. Finding and Discussion

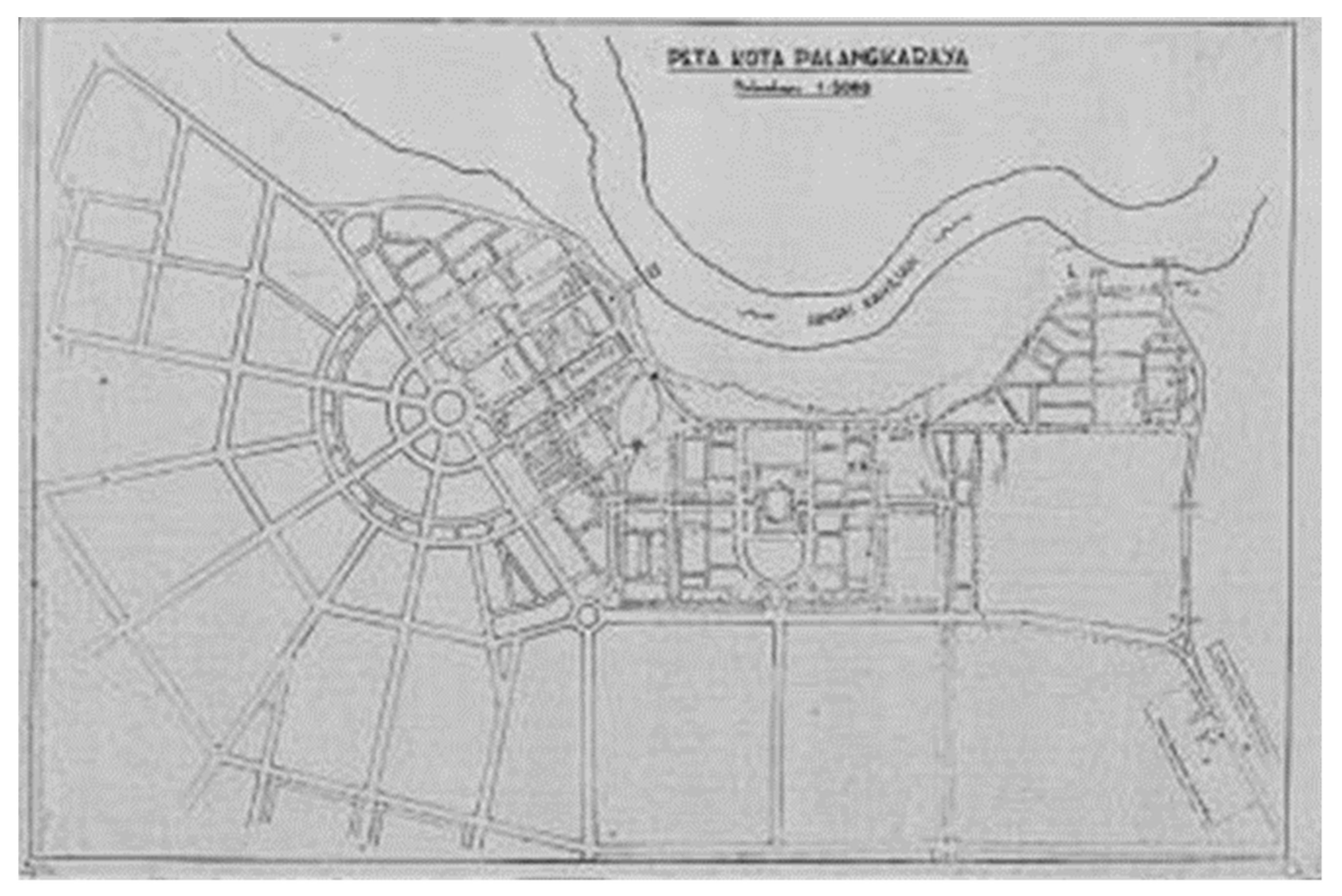

Before the 1970s, today's cities were still underdeveloped slums. Even long before the 1960s was only a village oriented towards a building (Betang). Scharer explained that these villages are more oriented toward the river[

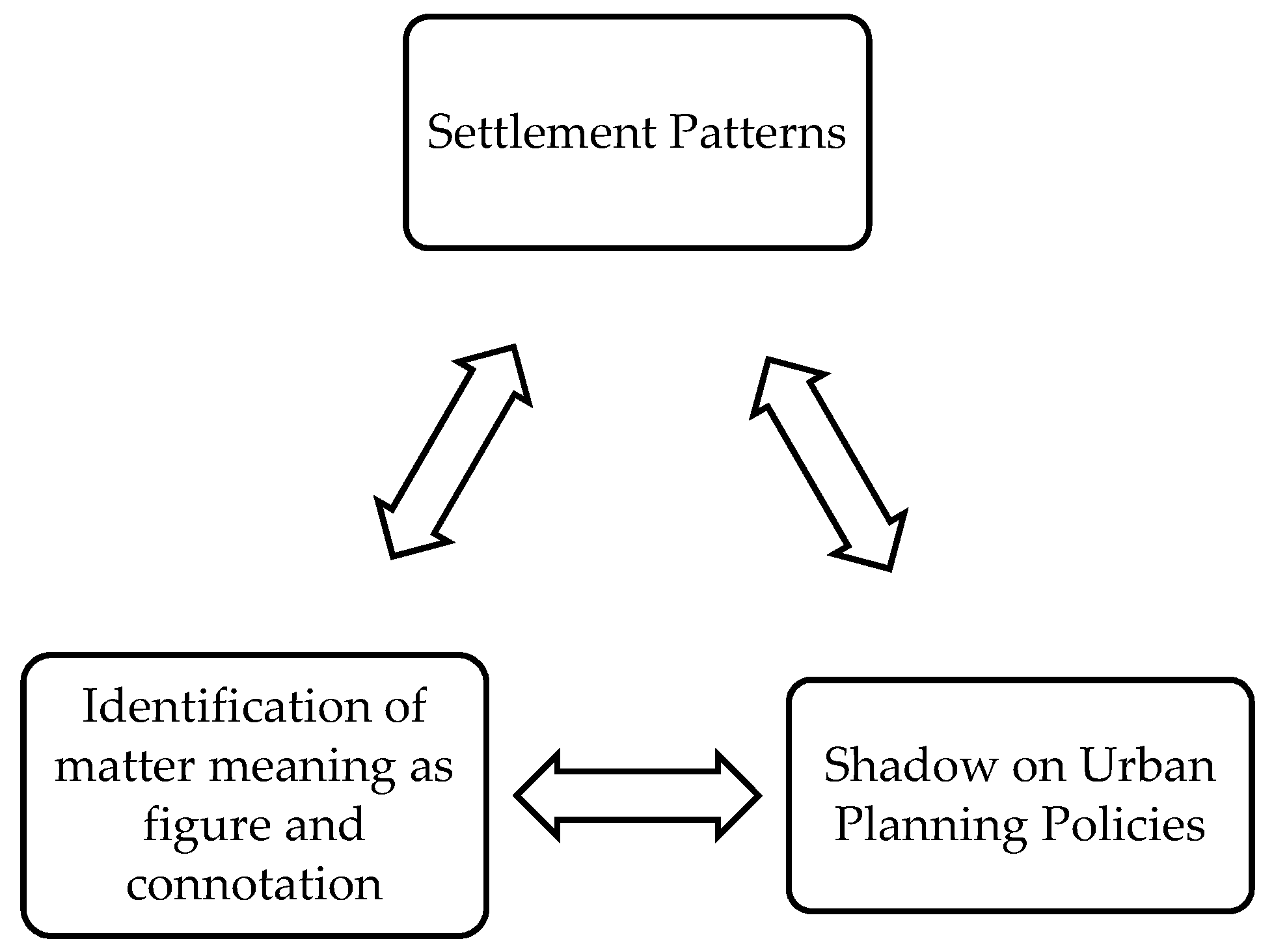

15]. Based on the total population in Central Kalimantan in 1976, there were 845,452 of the total population still in the village, sub-district, and district areas. The population that occupies the city is only 39,365 thousand people.

Table 1.

Total population of Central Kalimantan, by Gender per Regency and City 1976 (BPS, 1977) [

26].

Table 1.

Total population of Central Kalimantan, by Gender per Regency and City 1976 (BPS, 1977) [

26].

Meanwhile, Gunung Mas, East Barito, Katingan, and Murung Raya, still have the administrative status of assistant regent and have not fully become districts. Meanwhile, the population ratio between the regency capital and its sub-district areas was 1:3, and approximately 30% lived in urban areas. About 70% of the population was still in sub-districts or rural areas. By measuring based on this ratio, it shows that the total population in Central Kalimantan before the 1990s who lived in urban areas was 281,191 people. Thus the city was not an attraction to live for most of the population of Central Kalimantan.

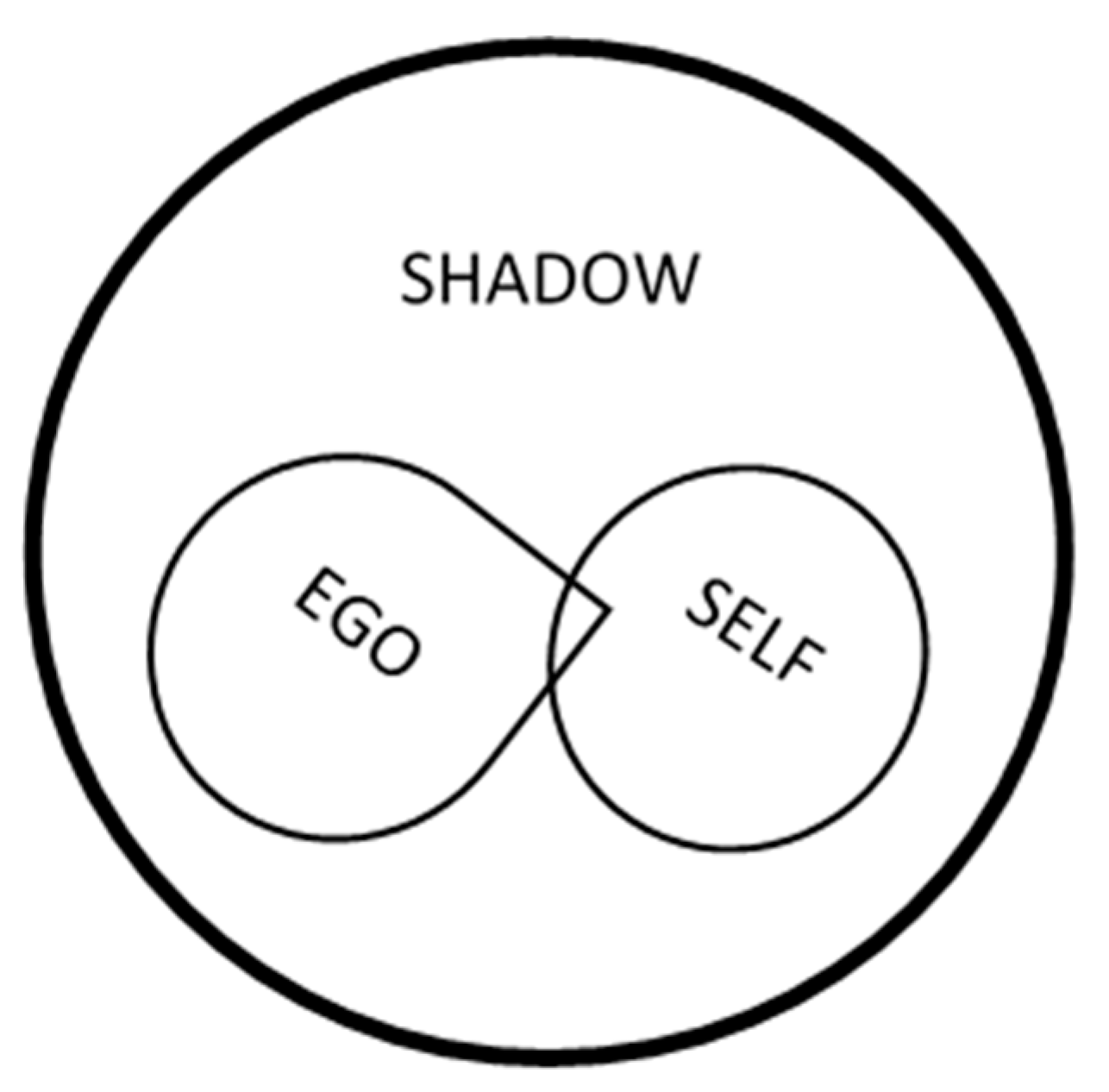

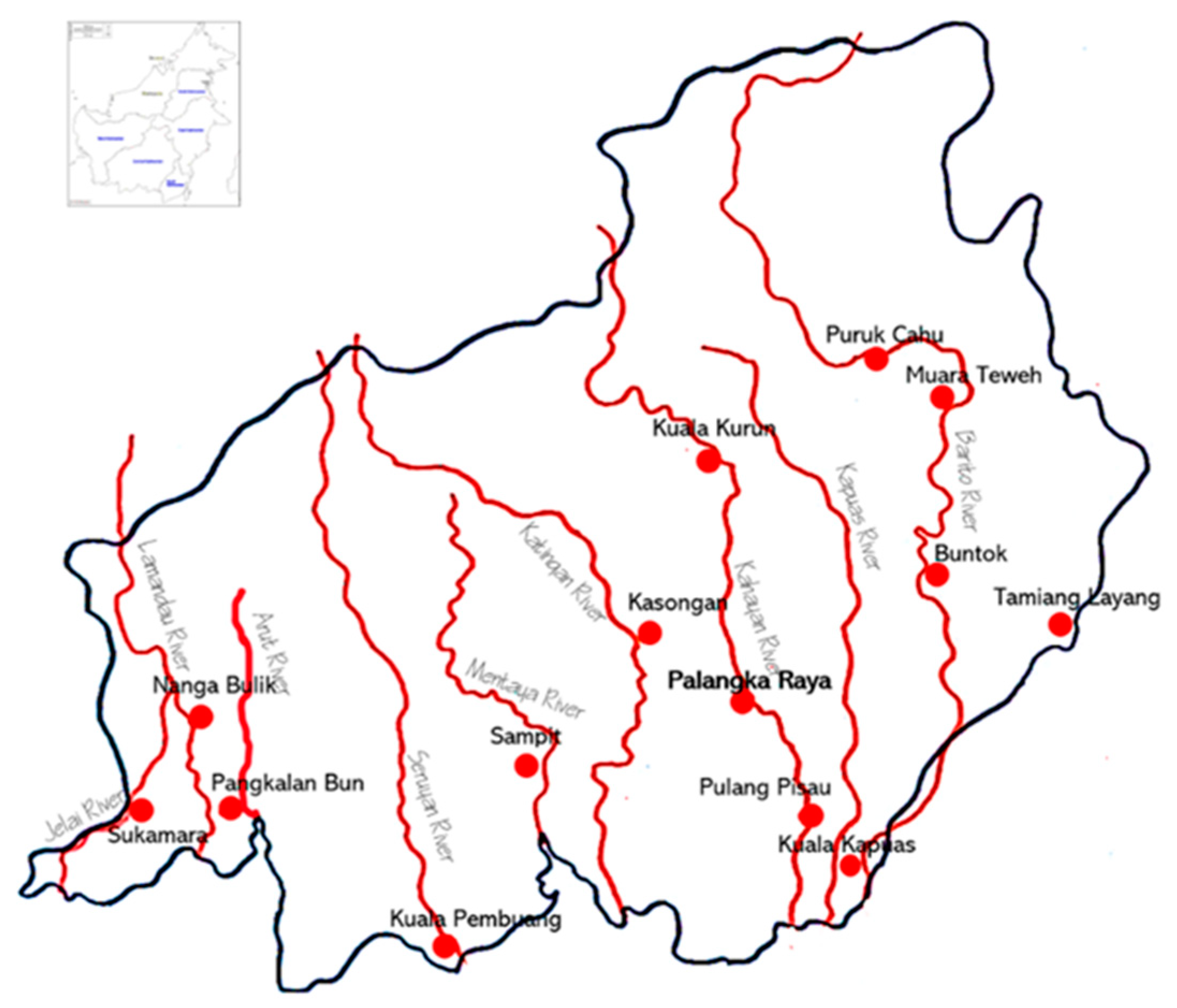

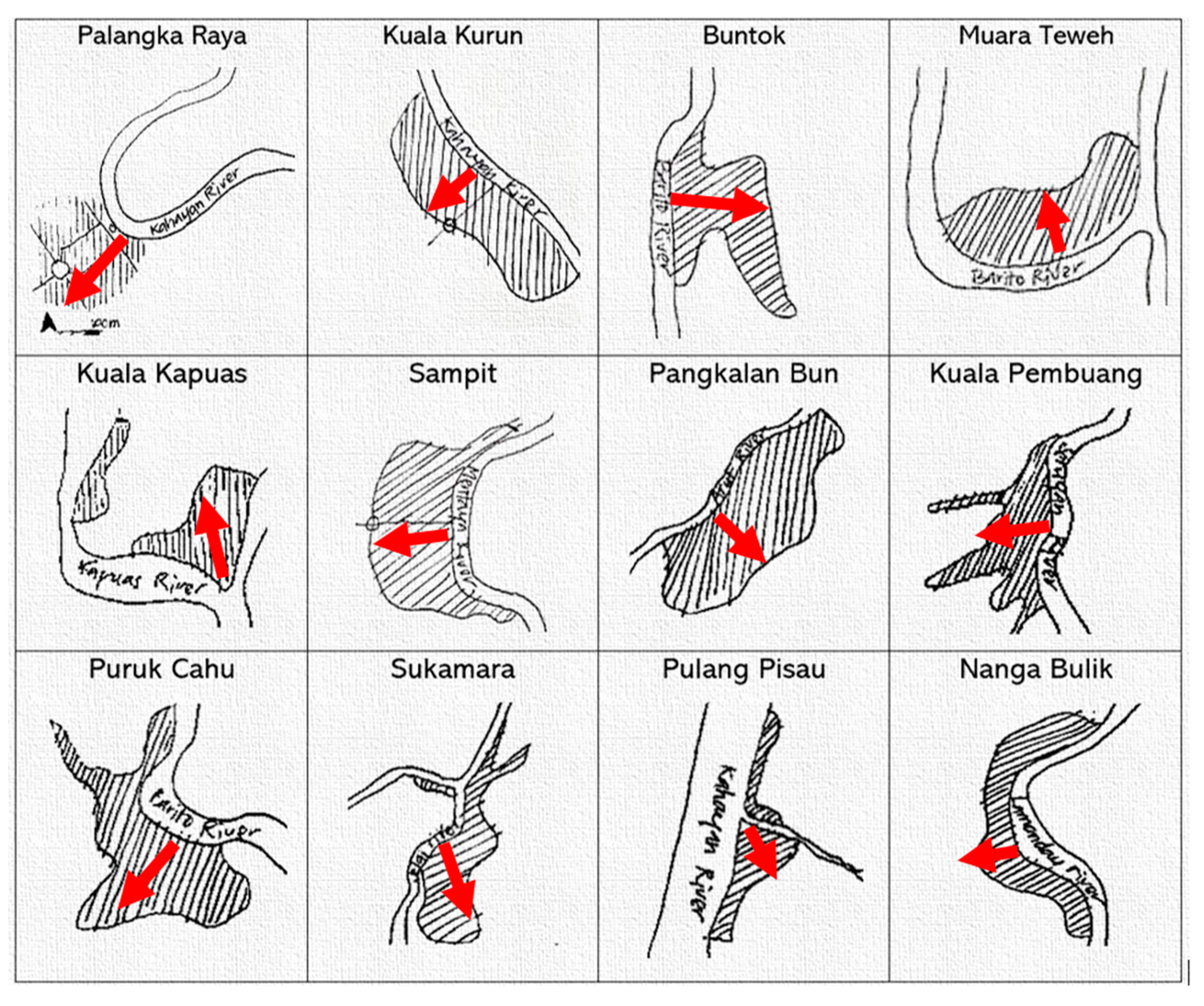

Figure 3.

Cities Morphological in Central Kalimantan, with a linear pattern before Trans-Kalimantan Road oriented in the 1990s. (Source: Analyses, 2023).

Figure 3.

Cities Morphological in Central Kalimantan, with a linear pattern before Trans-Kalimantan Road oriented in the 1990s. (Source: Analyses, 2023).

Meanwhile, cultural activities such as the Tiwah ritual in the Kaharingan belief are in rural areas in Central Kalimantan [

19]. So, trajectorial and transcendental thinking are found in the population in these rural areas. But on the other hand, the increase in population later forced them to leave the center of their village (betang) to develop their dwellings along the riverside because the river was a resource for their life at that time [

31]. Because of that, this thinking is very influential in making place in urban spaces in Central Kalimantan, especially the City of Palangka Raya.

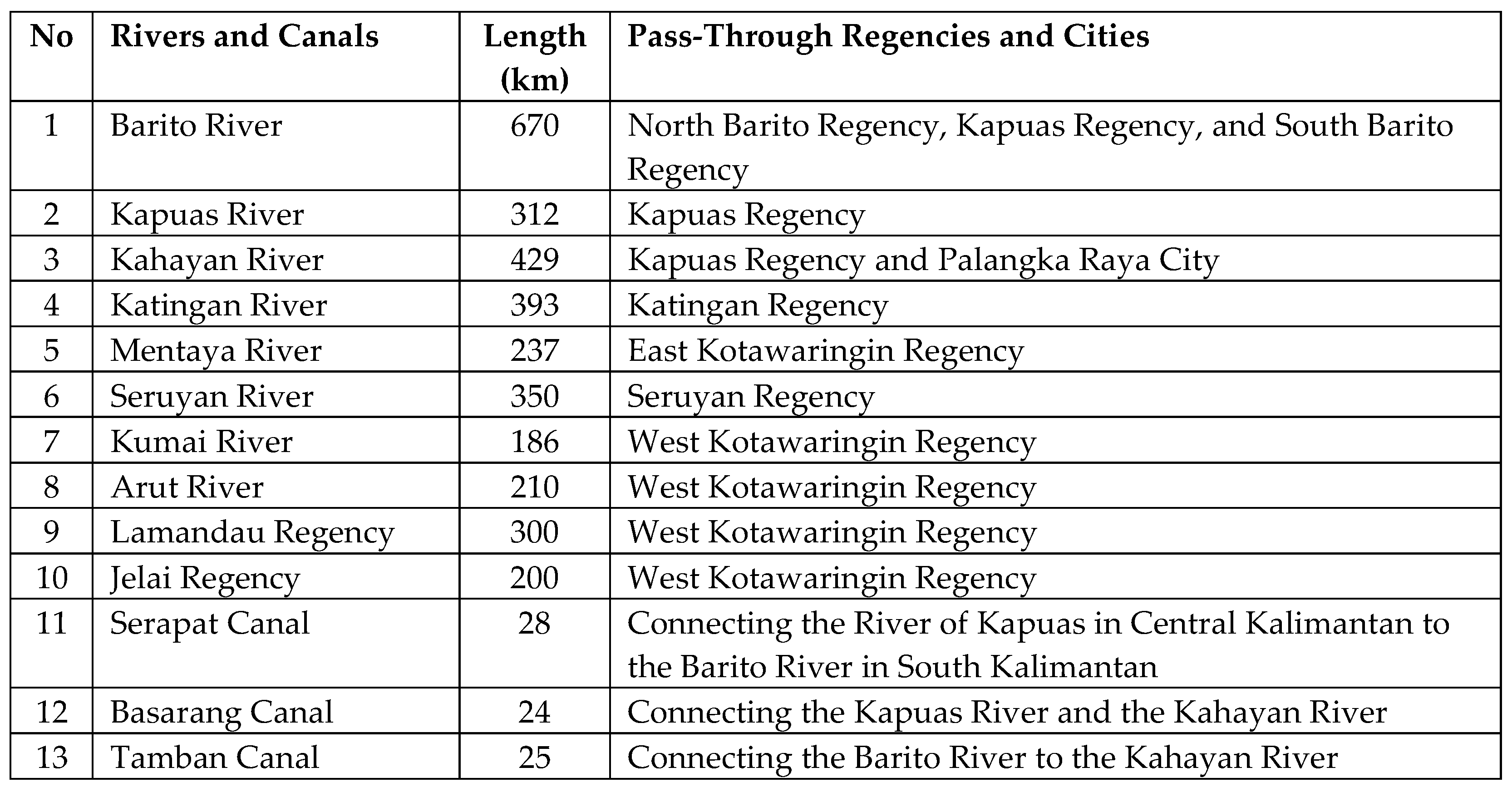

Figure 4.

River through the cities in Central Kalimantan (Source: Analyses, 2023).

Figure 4.

River through the cities in Central Kalimantan (Source: Analyses, 2023).

On the one side, the rivers in Central Kalimantan had a width almost the same as the estuary up to several hundred kilometers inland. It was very advantageous coupled with sufficient depth so that the rivers flow navigated far inland. The best distance to reach was in the rainy season, and this distance drastically drops in the dry season. An example was the Kahayan River. During the rainy, medium to large-size driver's vessels can sail as far as Kuala Kurun (Gunung Mas Regency) and Tewah, located a few hundred kilometers north of Palangka Raya. But during the dry reached Palangka-Raya was only a few hundred kilometers from the estuary been so hard. If comparing the reach distance in the dry season with the reach distance in the rainy season, the ratio is around 1:3 [

19]. This figure was not the same for all rivers because some even exceeded that ratio.

Table 2.

Rivers and Waterways in Central Kalimantan 1976 [

32].

Table 2.

Rivers and Waterways in Central Kalimantan 1976 [

32].

Large and medium-sized merchant ships from Banjarmasin sailed far into the interior of Barito (Murung Raya regency) when the rainy season [

33]. Ships measuring 1 to 5 tons sailed easily up to the Hanyu River on the Kapuas River. The Seruyan River can be navigated up to Tumbang Sanamang. Ships ranging in size from 750 to 1500 tonnes can only sail inland at a maximum distance of 100 kilometers. While transportation using rowing boats in the 1990s was very rarely done. Almost every river now serves only merchant ships, while the mobility of people from one place to another becomes faster and more economical by road.

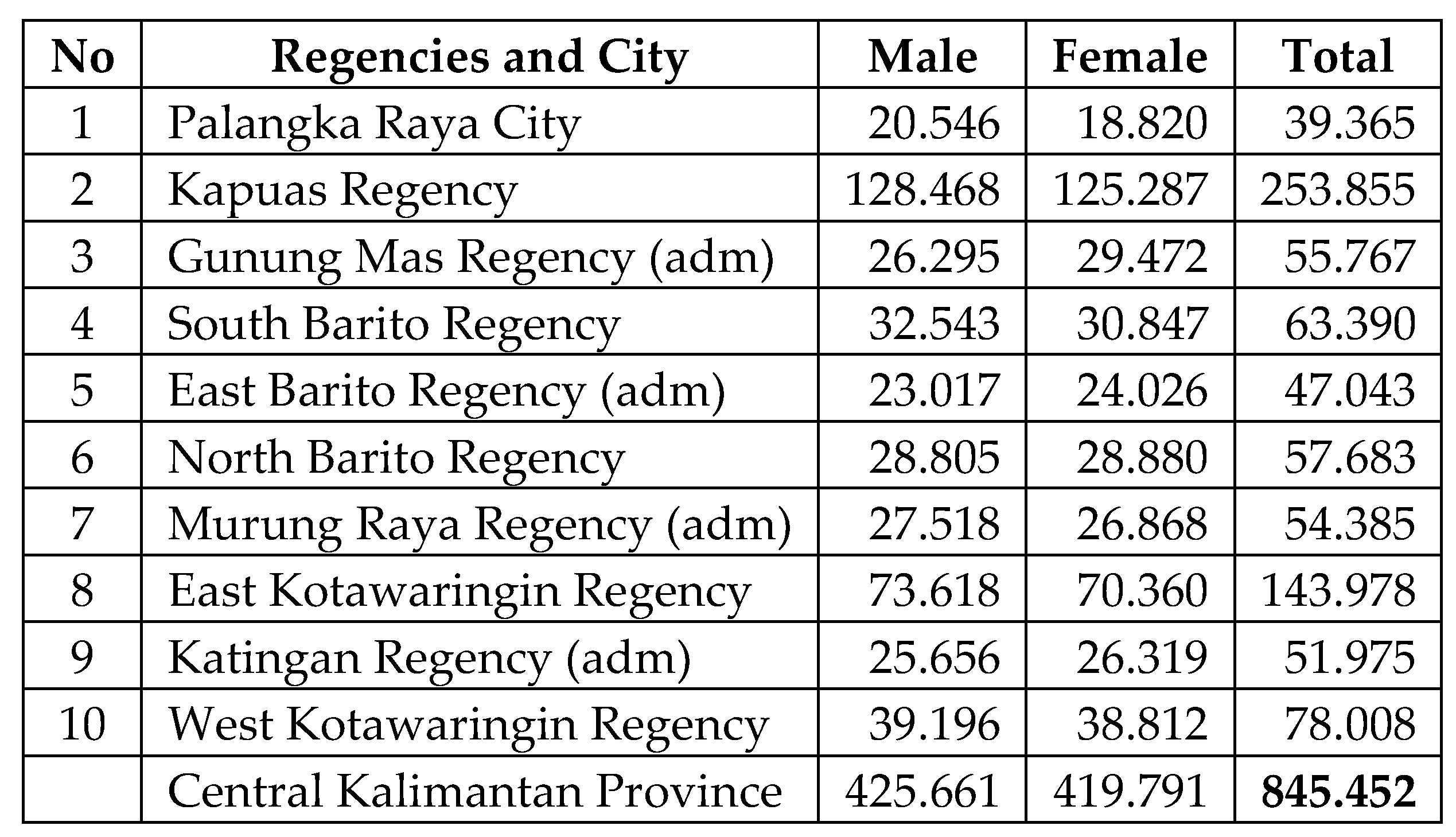

3.2. The Dayak People's Identity as Urban Planning Paradigm Before 1957

Thus, referring to the definition of the trope that becomes tropicality is a figure of meanings contained in the relationship between individuals and society in deep presenting space [

28,

34]. Before the 1990s, the Dayak Ngaju settlement had dominated most areas in the province of Central Kalimantan. This tribe consists of several sub-tribals, following the rivers of Lamandau, Arut, Kahayan, Katingan, Kapuas, and Barito, who believe in what their ancestors said and certain places that their elders identified. For tribes whose livelihoods are from the forest, farming, and depending on the river. Their villages or residences mean a temporary space in the world [

15,

21]. Dayak tribe divides its space into three parts, the heavenly (

ngambu), the human realm (

pambelum kalunen), and the underworld (

ngiwa)[

15]. Each of these spaces marks with figurines, such as rivers, sky, vegetation, houses, sculptures, and some animals.

The Tiwah ceremony escorts the spirits of ancestors or people who died earlier to the heavenly realms by the Kaharingan priest called Basir [

35]. It needs a betang that owns stairs seven steps, nine, or eleven to metaphor the sky levels. The number of steps varies depending on the position of the Betang in the river area and the tribe where the Betang is made. Usually, for Kahayan, the number of steps to the landing is seven. For the stairs, they call it

lampat, while for the landing stage, it is called

sandehan. On the stair, at the seventh steps, nine, or eleventh, the Dayak family owns the dead placed the coffin. Before the priest conveys the prayer to Heaven, the family or the priest of those dead man's bones cleans them in the water. Usually, the seventh, ninth, or eleventh steps are in the form of landings square. The peak ceremony is cleaning the bones or leftover meat residue until midnight [

35]. Because referring to the Dayak tribe, the night is darkness where life begins and ends. Then after the cleaning process is complete, the bones that were previously placed on the 7th of the steps stair or 9th or 11th, the Dayak Family owner those bones load them to the

Sandong. Sandong is the same house as betang but smaller and a metaphor for the incarnation of betang in heaven. Generally, the

Sandong of the Dayak Family constructs in front of the Betang, at the same height as the floor of the Betang, accompanied by a statue of the deceased's family, such as the mothers, fathers, or children.

Even though they are almost the same morphology, Sandong has striking differences from betang, especially in the building materials and decorations. Sandong is heaven's metaphor. So, the Dayak people made Sandong entirely from ironwood (Ulin). The

ulin tree is the most enduring type of wood on the island of Kalimantan. In the wood classification species for construction in Indonesia, ironwood is the first-class wood with first-class uses [

36]. This wood is tough and non-corrosive, resistant to weather changes. Dayak people deliberately made Sandong resemble Betang because betang is also a personification of Heaven. Sandong applies ironwood thin strips as roofing material or

sapau in the Dayak language. Likewise, ironwood is the main construction on its floor, called

laseh. On the sapau or part of the roof, some Sandongs decorate with some birds (

tingang) as personifications for a messenger from above that state the dead man had arrived in heaven [

37]. This carving bird always faces the Ngaju direction, which is the higher part of the upriver. While the back is a Palangka carving, a spirit boat that brings the souls and bones of people inside the Sandung to the higher realms (Heaven).

Betang is the big house of the Dayak tribe, built on stilts. Generally, ironwood is the principal material of the pillars of the stage, floor, and superstructure. However, the wall (tambing) that separates the room must be a construction of bark (nyamu) as the personification of the natural world to distinguish it from Sandong as a metaphor for heaven. By tying nyamu to the wall construction using smooth rattan, if damaged, it is easy to repair or replace it. Rattan (uwei-bajakah) is a type of forest-resistant rattan to heat and rain. This type of rattan is water-resistant, so it doesn't break or break easily when used. They used it to patch holes in boats. Sometimes, it was as a stick, a replacement nail. Nyamu is a ready-to-use material for constructing walls (tambing). There are three products from Nyamu. Firstly, the outer skin of the wood used for the outside wall is rougher. Second, Nyamu, which separates the interior more subtly. Third, the Dayak tribe uses the more delicate Nyamu for clothing-making materials. The height of the Betang adjusts to the number of stair steps. Betang stair separates into two parts, part one consisting of seven, nine, and eleven up to the landing. And the second ladder is a short odd number of steps until the ladder meets the Betang entrance. The entrance of the Dayak tribe calls it bauntunggang, while the door leaf they call atep.

The human space, for the Dayak tribe, is the space resulting from the marriage of

Ranying Hattala Langit (a male figure), ruler of the heavenly realms governing in the sky [

37], with

Kabentaran Bulan Bawin Jata (a female figure) governing the underworld [

15]. Because of this marriage, Dayak people were born [

16]. For the Dayak tribe, the oldest people are the center of life. Thus parents or the elder are always the standard or orientation of their life. Then this becomes the meaning implemented in the Betang space. As an honor, the life of Dayak always starts with the oldest. When built Betang, the first pillar inserted in the soil was the oldest one (

jihi bakas). In this sense, the

bakas pillar is a manifestation of the age of the building, as the origin and story of the life of the tribal children who built the betang. Therefore, a male and female tiger statue on the seventh step of the stairs signs people before entering the Betang.

The statues of male and female personifications also signify place and direction (wayfinding). Men are always in the downriver (

Ngawa), while women are always in the upper river (

Ngaju). Likewise, regarding the position in the Betang, the old lady and man were always in opposite places. The statues and the Sandong in front of the Betang must face the rising sun as a sign beginning of life, both on earth and in heaven. So that in this way, Betang must also face toward the rising sun (

pambelum andau). Scharer (1963) calls it an orientation of the Dayak tribe where the opposite part of

pambelum andau is

pambeleb andau. Thus there are four directions of Dayak human orientation:

pambelum andau, pambeleb andau, ngaju, ngawa [

15]. The meaning of the

pambelum andau is all the good things that come, the beginning of the light of life. This is the best choice for constructing houses, villages, and cities in the world of Dayak people's beliefs.

Pambeleb andau is all that is unfortunate, and the end of life goes to the dark. So that there are no Dayak tribes who build their houses facing this orientation [

15].

Ngaju is all the classics, oldest, and antiques where Dayak people stored treasures and prosperity. While

Ngawa is, all the new knowledge and technology comes from. Why was that? Because the only new thing came from the downstream river (ngawa).

Jihi Bakas becomes the beginning of the boundaries of human space and a center for orientation and territory. For the Dayak tribe, the Tiwah ceremony for summoning spirits must use a gong (garantung). And garantung sound is also an invisible boundary mark for a Dayak tribe's territory. Gong is a tool made of bronze that protrudes round in the middle as a center point to be hit. The history of this tool comes from Vietnam around 500 BC. Gong invented in China around 200 BC and entered Indonesia is around 500 AD. Once upon a time, if someone went out into the fields or hunted in the forest, got lost, and never found his way back, the Dayaks went to the forest where those people who got lost, while got beating the

garantung, called them back [

16]. Dayak people hung and placed the

garantung on the

Jihi bakas of Betang as a starting place. Thus the betang is the center of Dayak human spatial orientation. Because as a center of orientation, it was usually in the betang that a tribal chief resides, older and kids.

The underworld is the realm of

Jata, the god who rules over that realm, where rivers and water are personifications of the underworld[

16].

Jata is the image of a water dragon who rules over wealth (giving wealth) and the underworld, a jealous goddess figure. The image of

Jata's wealth it contains always applied to a

balanga (jar) and gold. The ceramic jar origin was from the Yuan dynasty in China around the 12th century AD, which entered Kalimantan due to the trade carried out by the Chinese[

38].

Jata is a metaphor for the form of a snaking river. A Dayak who dies will enter the realm of death (liau) or hades, where the Jata reigns[

15]. Therefore, during the Tiwah ceremony, the Laluhan ceremony always precedes the Tiwah. In this ritual, the Dayak priest expels reinforcements or evil spirits before entering the human realm or to Betang. Thus, the river is always the personification of the lower part (

ngiwa) as a sacred and frightening place. For Dayak people, a river was a depth place, so no one knew what was in it (mysterious). To cross the river, the Dayak tribe needs a spirit boat from the gods above that protects their journey. They called the boat's name

Palangka[

35]. They called the boat's name Palangka. Palangka is a spirit boat, which is a boat used by the gods above to descend to the human realm. So the ruler of the underworld doesn't interfere. Because the river is also a sacred place, the Dayak people clean their bodies in the river.

In this context, before entering the Betang, someone must clean his body in the river, then go up (

lumpat kan ngambu)[

16]. Because when the Dayak people go to the fields, they don't bathe from the betang but go downstairs (

muhun kan ngiwa). These two aspects of daily life are a benchmark when the Dayak people start their day. Thus they construct a connection between the ngiwa realm and the human realm. Marking it, the Dayak people make a ladder (hejan) that connects the two. There is a difference between the hejan, which they use to climb the Betang, and the hejan, which they use to move their bodies from the ngiwa realm (jata) to the

ngambu realm. The hejan, from ngiwa to ngambu, is unpredictable because the bottom goes into the river. To climb it, it is forbidden to look back. For the Dayak tribe, looking back is seeing the darkness or the past. The Dayak tribe's returns from the farms usually start at dusk and enter the darkness. At this time the era there were no lights or lighting. So, before it gets dark, they should go home. Because of this, if people climb the

hejan (stairs) and then look backward, they can fall or slip because the body becomes unbalanced.

3.3. The Existence of Vernacular Settlement Patterns Along the River in Central Kalimantan After Road Political Project in the 1990s.

However, the story above is difficult to repeat because of the change in the paradigm of the Dayak people, who no longer see the river as part of their daily life. Today, several major rivers and tributaries in Central Kalimantan remain the means of transportation for Dayak people only to send goods, such as palm and coal, because not all the roads that connect certain villages or towns properly deliver those goods. Likewise, with the Trans-Kalimantan road project. It doesn't go through all the districts and the city in Central Kalimantan province. Not all rivers become accessible to replace roads, and not all villages can contact the city by road, which is about 5-7%. The rivers in Central Kalimantan are as follows:

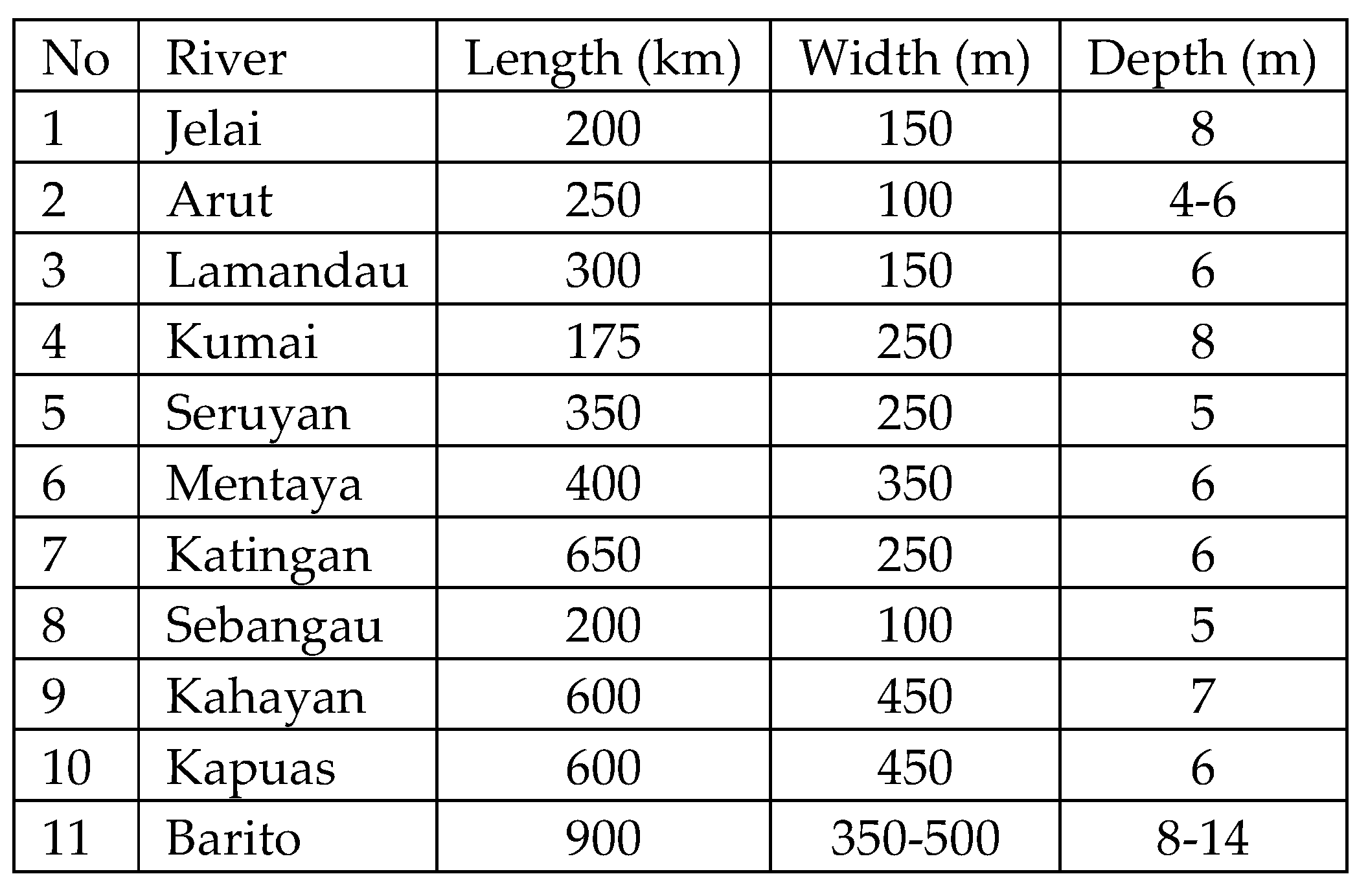

Table 3.

Rivers in Central Kalimantan [

39].

Table 3.

Rivers in Central Kalimantan [

39].

Based on the morphological classification, the pattern of settlements that develop along the river consists of two parts, river-oriented cities, and road-oriented cities. Road-oriented cities are cities that have now become district capitals. Meanwhile, cities that are not road-oriented before the Trans Kalimantan Road Project exist, but these cities have already become extensive settlements along the river.

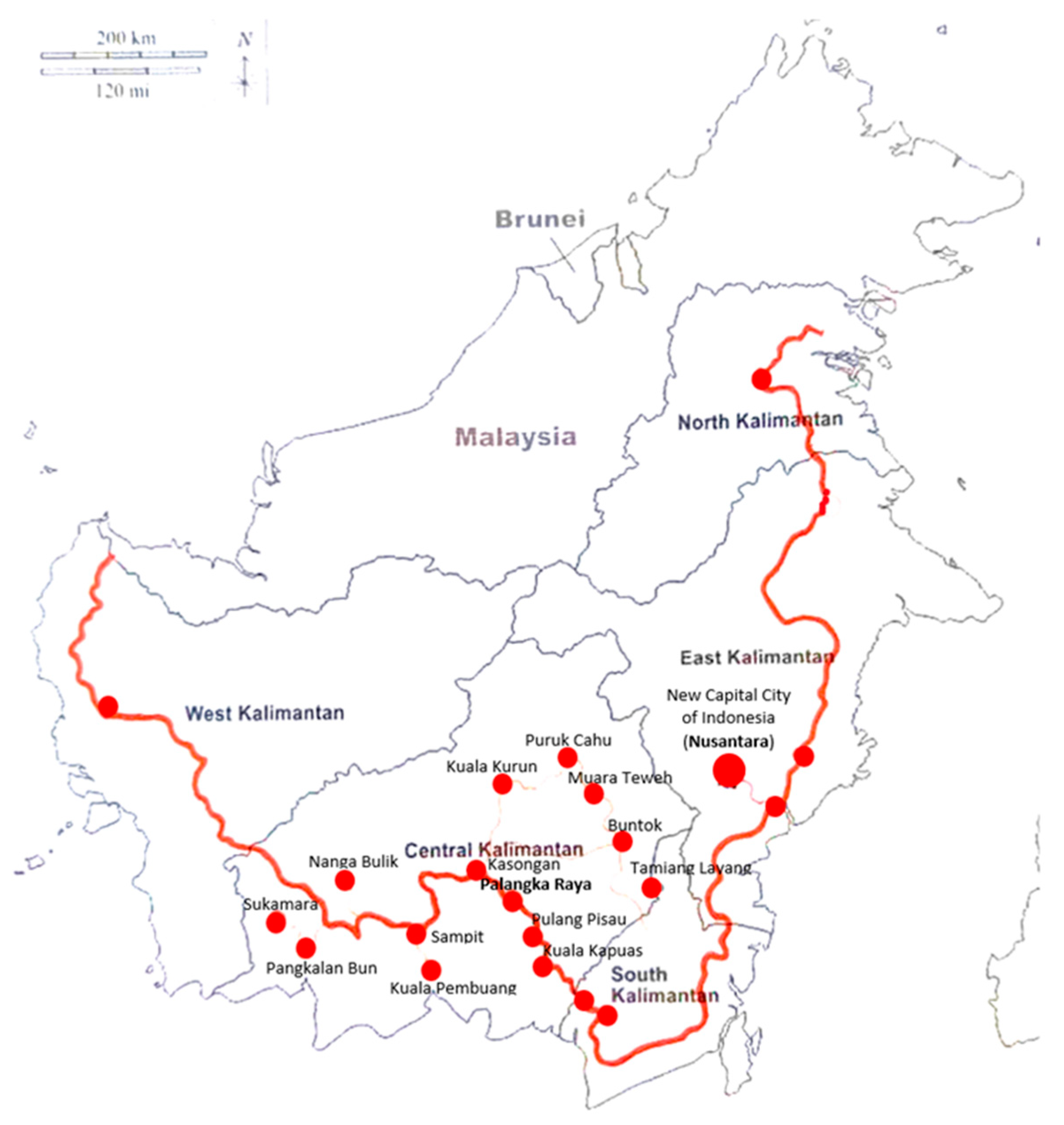

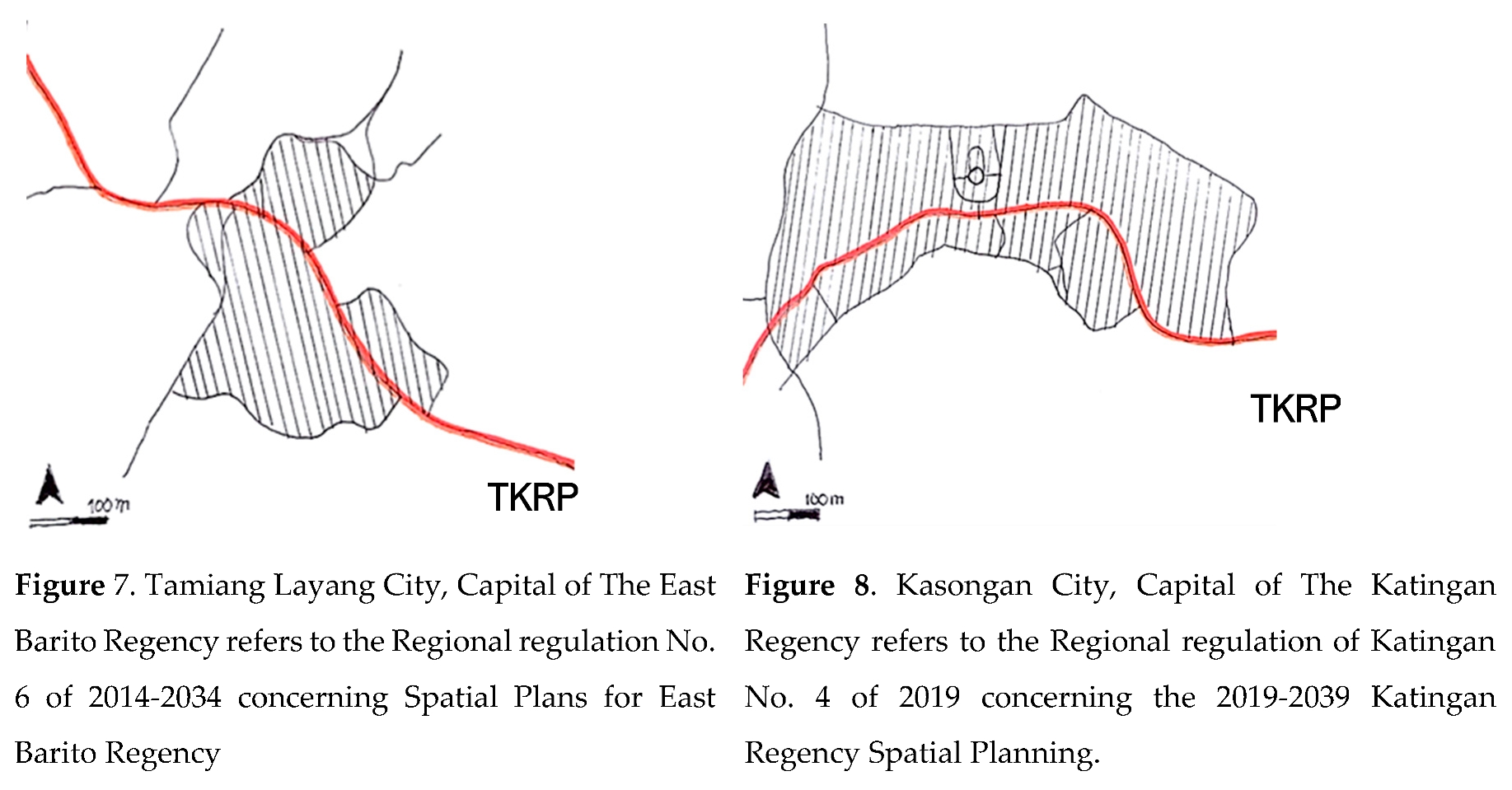

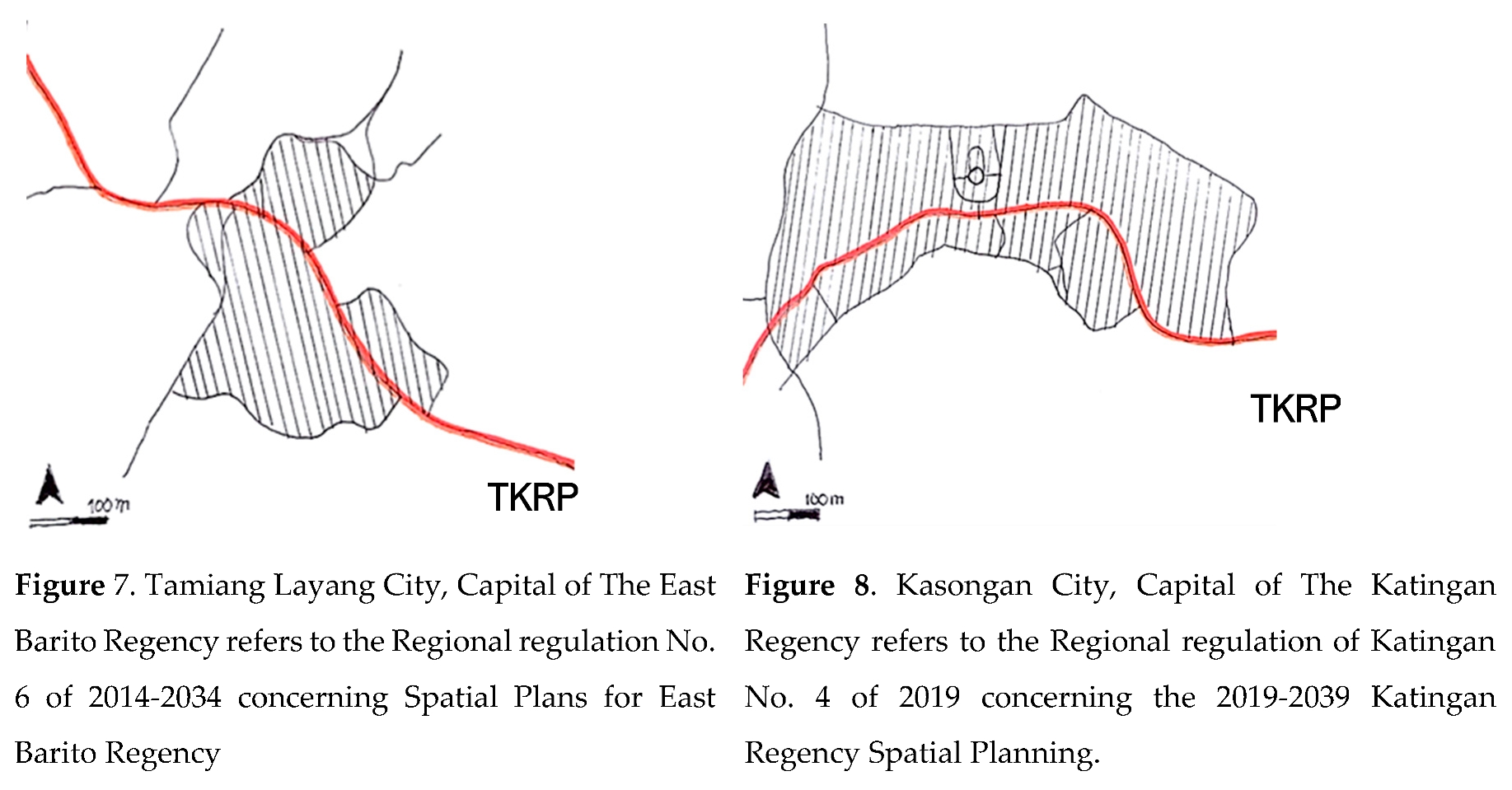

Figure 5.

Trans Kalimantan Roads Project (TKRP) across Central Kalimantan is 2002 km. (Source: Analysis, 2023).

Figure 5.

Trans Kalimantan Roads Project (TKRP) across Central Kalimantan is 2002 km. (Source: Analysis, 2023).

Figure 6.

Cities morphological in Central Kalimantan on Riverbanks after Trans-Kalimantan Road Project (source: Analysis, 2023).

Figure 6.

Cities morphological in Central Kalimantan on Riverbanks after Trans-Kalimantan Road Project (source: Analysis, 2023).

Two cities are developing along the road, Tamiang Layang City and Kasongan City. The town of Tamiang Layang had a population of 43043 before the 1990s. With an area of 32,545 km2 with a population density of 4.5 people/km2. Kasongan City at that time had not yet been formed. These two cities developed in 2002 when the Indonesian government implemented the regional expansion policy. Then the existence of the Trans Kalimantan Road Project has made policies for cities in Central Kalimantan Province to switch to roads, especially in new cities such as the city of Kasongan, the capital of Katingan and Tamiang Layang districts in East Barito capital.

Meanwhile, from the condition of the cities that used to be oriented towards the river, they slowly developed towards the Trans Kalimantan Road. The attraction makes the city widen. This policy then makes land development a commodity. Following this development, there is a problem of scarcity of land in the city center. Coupled with the spatial planning law policy in Indonesia in 2007, these cities no longer view water (vernacular) as part of urban planning. Because the law does not regulate a city plan related to water. As a result, issues arose around the city's plan, which was more concerned with its position on the mainland than near the river or water.

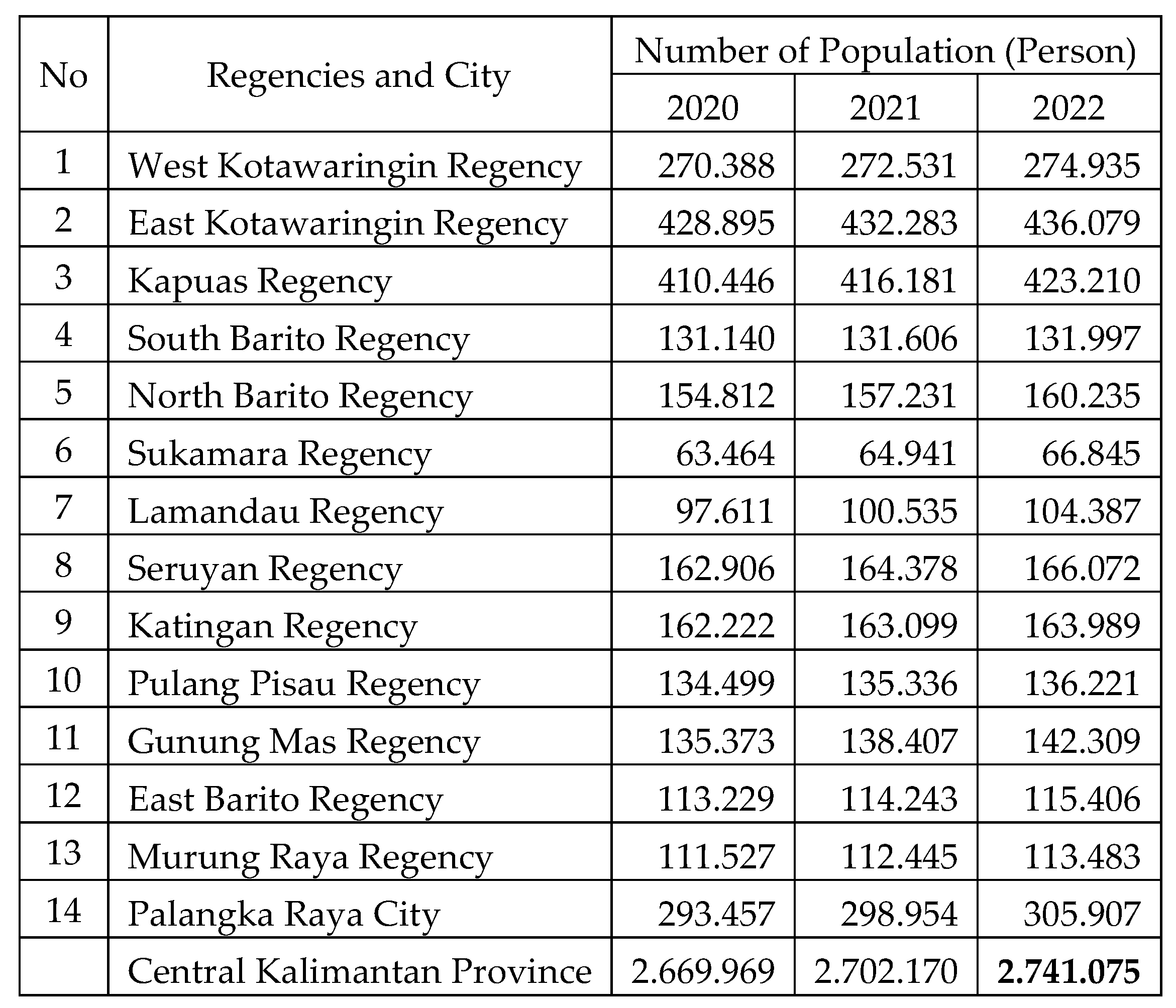

Table 1.

Total population of Central Kalimantan 2022 [

39].

Table 1.

Total population of Central Kalimantan 2022 [

39].

The change in the orientation of cities to roads, then the politics of roads, have influenced the development of these cities. Begin from the flow of goods and passenger transportation has converted into automobile transportation patterns within the city and also out of town. Governor Regulation Number 6 of 2021 concerning domestic service travel, no longer mentions that trips can use rivers. As a result, land that is beside the main roads becomes an expensive commodity. The development of the city's capitalization has become faster than before. Local cultural homogeneity no longer confines cities, but now cities become open to more heterogeneous outside cultures. With the population increasing to 2,741,075 in 2022, almost three and a half times before the 1990s, which was only 845,452 people, it shows that the development of cities in Central Kalimantan is experiencing rapid. But the growth in urban areas has emerged some issues regarding land ownership, segregation, and informal-formal.