Submitted:

31 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Secure Attachment and Self-Concept

2.2. Secure Attachment, Resilience and Self-Concept

2.3. Secure Attachment, Positive Self-Esteem and Self-Concept

2.4. Secure Attachment, Resilience, Positive Self-Esteem and Self-Concept

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

3.4. Procedure

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive and Correlational Análisis

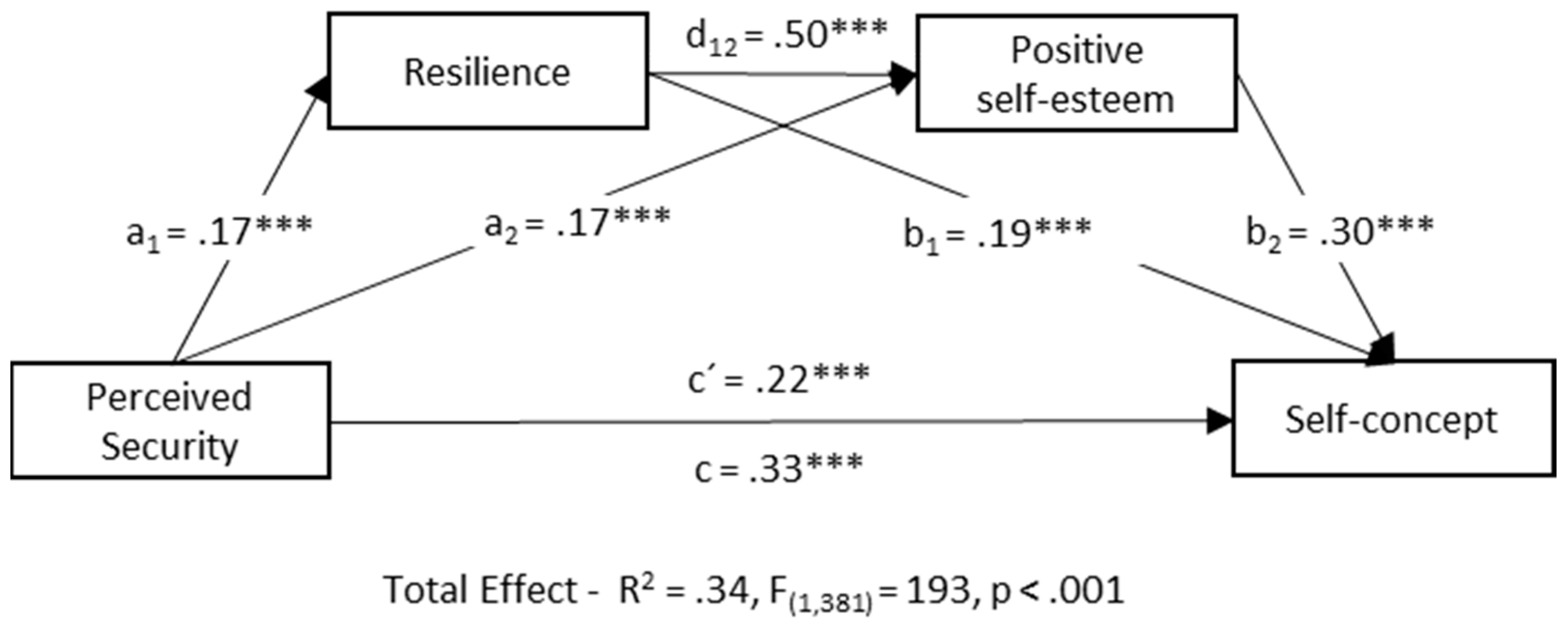

4.2. Sequential Mediation Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council of Europe. Recommendation REC (2006)19 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on policy to support positive parenting. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, 2006.

- González, R. Queriendo se entiende la familia. Guía de intervención sobre parentalidad positiva para profesionales. Save the Children, 2013.

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, N.J, USA, 1978.

- Boldt, L. J.; Kochanska, G.; Grekin, R.; Brock, R. L. Attachment in middle childhood: Predictors, correlates, and implications for adaptation. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2016, 18, 115-140. [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P. R.; Sapir-Lavid, Y.; Avihou-Kanza, N. What’s inside the minds of securely and insecurely attached people? The secure-base script and its associations with attachment-style dimensions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 615-633, doi:1037/a0015649.

- Verhaeghen, P.; Hertzog, C. The Oxford Handbook of emotion, social cognition and problem solving in adulthood. Oxford Library of Psychology: UK, 2014.

- Clark, S. E.; Symons, D. K. A longitudinal study of Q-sort attachment security and self-processes at age 5. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2000, 9, 91-104. [CrossRef]

- Çetin, F.; Tüzün, Z.; Pehlivantürk, B.; Ünal, F.; Gökler, B. Attachment Styles and Self-Image in Turkish Adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 840-848. [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, L. A.; Egeland, B.; Carlson, E.; Collins, W. A. Placing early attachment experiences in developmental context. In The power of longitudinal attachment research: From infancy and childhood to adulthood; Grossmann, K.E, Grossmann, K. Waters, E., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 48 – 70.

- Deniz, M.; Kurtuluş, H. Self-Efficacy, Self-Love, and Fear of Compassion Mediate the Effect of Attachment Styles on Life Satisfaction: A Serial Mediation Analysis. Psychological reports. 2023, 12, 332941231156809. [CrossRef]

- Grotberg, E. The International Resilience Project: Promoting Resilience in Children. Universidad de Wisconsin, USA, 1995.

- Masten, A. S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227-238. [CrossRef]

- Garmezy, N. Reflections and commentary on risk, resilience, and development. In, Stress, risk and resilience in children and adolescents. Processes, mechanisms and interventions; Haggerty, R.J., Sherrod, L.R., Garmezy, N., Rutter, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambrigde, UK, 1994, pp. 119.

- Luthar, S. S. Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades. In Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation; Cicchetti, D. Cohen, D.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 739–795.

- Atwool, N. Attachment and resilience: implications for children in care. Child. Care. Pract. 2006, 12, 315-330. [CrossRef]

- Tiet, Q. Q.; Bird, H. A.; Davies, M.; Hoven, C.; Cohen, P.; Jensen, P. S.; Goodman, S. Adverse life events and resilience. J. Amer. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychia. 1998, 37, 119-200. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965.

- Kerns, K. A.; Klepac, L.; Cole, A. Peer relationships and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in the child–mother relationship. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 457-466. [CrossRef]

- Trzesniewski, K. H.; Donnellan, M. B.; Robins, R. W. Stability of self-esteem across the life span. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 205-220. [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; Merrick, S.; Treboux, D.; Crowell, J.; Albersheim, L. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child. Develop. 2000, 71, 684-689. [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R. G.; Hunter, J. J. Attachment and psychosomatic medicine: Developmental contributions to stress and disease. Psychosom. Med. 2001, 63, 556-567. [CrossRef]

- Mestre Escrivá, V.; Samper García, P.; Pérez-Delgado, E. Clima Familiar y desarrollo del autoconcepto. Un estudio longitudinal en población adolescente. Rev. Iberoam. de Psicol. 2001, 33, 243-259.

- Lila, M.; Musitu, G.; Molpeceres, M. A. Familia y Autoconcepto. En Psicosociología de la familia; Musitu, G., Allatt, P., Eds.; Albatros: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1994, pp.83-103.

- Felson, R. B.; Zielinski, M. A. Children’s self-esteem and Parental Support. J. Marriage. Fam. 1989, 51, 727-735. [CrossRef]

- Lila, M.; Musitu, G.; García, F. Comunicación familiar y autoconcepto: Un análisis relacional. R. Orient Edu Vocac, 1993, 6, 67-85.

- Bach, E.; Darder, P. Sedúcete para seducir. Vivir y educar las emociones. Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2002.

- Noller, P.; Callan, V. The adolescent in the family. Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Higgins, E. T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319-340. [CrossRef]

- Scharfe, E.; Bartholomew, K. Reliability and stability of adult attachment patterns. Pers. Relatsh. 1994, 1, 23-43. [CrossRef]

- Poole, J.; Dobson, K.; Pusch, D. Childhood adversity and adult depression: The protective role of psychological resilience. Child. Abuse. Negl. 2017, 64, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S.; Reed, M. G. J. Resilience in development. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002, pp. 74-88.

- Kumpfer, K. L. Factors and processes contributing to resilience: The resilience framework. In Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations; Glantz, M.D. Johnson, J.L., Eds.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 1999, pp. 179-224.

- Infurna, F. J.; Luthar, S. S. Resilience to major life stressors is not as common as thought. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 11, 175-194. [CrossRef]

- Zeinab, A.; Fereshteh, M.; Leili, P. The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in relation between attachment styles and marital satisfaction. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 2, 59-70.

- Deci, E. L.; Ryan, R. M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Laible, D. J.; Thompson, R. A. Mother–child discourse, attachment security, shared positive affect, and early conscience development. Child. Develop. 2000, 71, 1424-1440. [CrossRef]

- La Guardia, J. G.; Ryan, R. M.; Couchman, C. E.; Deci, E. L. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfilment, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 367-384. [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H.; Pajares, F. The development of academic self-efficacy. In Development of achievement motivation; Wigfield, A. Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 15–31. [CrossRef]

- Shahar, G.; Henrich, C. C.; Blatt, S. J.; Ryan, R. M.; Little, T. D. Interpersonal relatedness, self-definition, and their motivational orientation during adolescence: A theoretical and empirical integration. Develop. Psychol. 2003, 39, 4701-483. [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E. H. Identity: Youth and crisis. W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1968.

- Wu, C. H. The relationship between attachment style and self-concept clarity: The mediation effect of self-esteem. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2009, 47, 42-46. [CrossRef]

- Cornellà-Font, M. G.; Viñas-Poch, F.; Juárez-López, J. R.; Malo-Cerrato, S. Risk of addiction: Its prevalence in adolescence and its relationship with security of attachment and self-concept. Clinical Health. 2020, 31, 21-25. [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. M. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 21, 261-302. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, J.; Ji, S.; Hai, Y. Resilience and self-esteem mediated associations between childhood emotional maltreatment and aggression in Chinese College Students. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W.; Byrne, B. M.; Shavelson, R. J. A multifaceted academic self-concept: Its hierarchical structure and its relation to academic achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 366-380. [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R. W.; Widaman, K. F. Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1271-1288. [CrossRef]

- Balluerka, N.; Lacasa Saludas, F.; Gorostiaga, A.; Muela, A.; Pierrehumbert, B. Versión reducida del cuestionario CaMir (CaMir-R) para la evaluación del apego. Psicothema. 2011, 23, 486-494.

- García, F. & Musitu, G. Autoconcepto Forma 5 AF-5. TEA Ediciones, 2014.

- Connor, K. M.; Davidson, J. R. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003, 18, 76-82. [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Sills, L.; Stein, M. B. Psychometric Analysis and Refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-Item Measure of Resilience. J. Trauma. Stress. 2007, 20, 1019-1028. [CrossRef]

- Notario-Pacheco, B.; Solera, M.; Serrano, M. D.; Bartolomé, R.; García-Campayo, J.; Martínez-Vizcaino, V. Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the 10 item Connor -Davidson Resilience Scale (10 item CDRISC) in young adults. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2011, 9, 63-68. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Albo, J.; Núñez, J. L.; Navarro, J. G.; Grijalvo, F. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: translation and validation in university students. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 458-467.

- Tabachnick, B. G.; Fidell, L. S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2018, ISBN 978-01-3479-054-1.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Routledge, New York, NY, USA, 1988.

- Tofighi, D.; Thoemmes, F. Single-level and multilevel mediation analysis. J. Early. Adolesc. 2014, 34, 93-119. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, M. Q.; Qhiou, H. Z. Mediation analysis and effect size measurement: retrospect and prospect. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 28, 105–111.

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Kaur, J.; Rana, J. S.; Kaur, R. Home environment and academic achievement as correlates of self-concept among adolescents. Stud. Hom. Comm. Scien. 2009, 3, 13-17. [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M. F.; Batool, A.; Hafeez, S. Relationship between Perceived Quality of Home Environment and Self-Concept of Students at Undergraduate Level. Gl. Sociol. Rev. 2021, 6, 70-78. [CrossRef]

- Torres, A; Rodrigo, M.J. La influencia del apego y el autoconcepto en los problemas de comportamiento de los niños y niñas de familias en desventaja socioeconómica. Educatio Siglo XXI. 2014, 32, 255-278. [CrossRef]

- Chentsova, Y.; Choi, I.; Choi, E. Perceived parental support and adolescents’ positive self-beliefs and levels of distress across four countries. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I.; Augusto-Landa, J.M.; Quijano-López, R.; León, S. Self-concept as a mediator of the relation between university students’ resilience and academic achievement. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pilowsky, D.; Wickramaratne, P.; Nomura, Y.; Weissman, M. Family discord, parental depression and psychopathology in offspring: 20-year follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2006, 45, 452-460. [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, K.; Surkan, P.; Fombonne, E.; Chollet, A.; Melchior, M. Childhood friendships and psychological difficulties in young adulthood: an 18-year follow-up study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2015, 24, 815-826. [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Jaffee, S. R. The multiple determinants of parenting. In Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation, 2nd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D.J., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2006, pp. 38-85.

- McLeod, B. D.; Weisz, J. R.; Wood, J. J. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 10, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child. Develop. 1996, 67, 3296-3319. [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K.; Klimstra, T. A.; Duriez, B.; Van Petegem, S.; Beyers, W. Personal identity processes from adolescence through the late 20s: Age trends, functionality, and depressive symptoms. Soc. Develop. 2013, 22, 701-721. [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P. Attachment in adulthood. Structure, Dynamic and Change. Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017 .

- Cui, L.; Morris, A.; Criss, M.; Houltberg, B.; Silk, J. Parental Pychological control and adolescent adjustment: the role of adolescent emotion regulation. Parent. Scien. Pract. 2014, 15, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Kochanska, G.; Kim, S. Early attachment organization with both parents and future behavior problems: From infancy to middle childhood. Child Develop. 2013, 84, 283-296. [CrossRef]

- Collins, N. L.; Feeney, B. C. A safe haven: an attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 1053–1073. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 313-324. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N = 383 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | Mean (SD) | 28.52 (12.23) |

| Sex | Men | 91 (23.8%) |

| n (%) | Women | 292 (76.2%) |

| Education level | Primary studies or less | 8 (2.1%) |

| n (%) | Secondary studies or basic training | 20 (5.2%) |

| Vocational training | 65 (17%) | |

| High school studies | 37 (9.6%) | |

| University studies | 253 (66.1%) | |

| Type of family life | Live alone | 19 (5%) |

| n (%) | Live with friends | 25 (6.5%) |

| Single parent family | 108 (28.2%) | |

| Heteroparental family without children | 40 (10.4%) | |

| Heteroparent with children | 177 (46.2%) | |

| Others | 14 (3.7%) |

| Variables | M | SD | A | K | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Perceived security | 4.23 | .91 | -1.47 | 1.72 | - | |||

| 2 Self-concept | 3.64 | .52 | -.33 | -.01 | .58*** | - | ||

| 3 Resilience | 3.93 | .68 | -.45 | -.44 | .22*** | .56*** | - | |

| 4 Positive self-esteem | 4.28 | .66 | -.81 | .29 | .35*** | .67*** | .57*** | - |

| Resilience (M1) |

Positive Self-esteem (M2) | Selft-concept (criterion variable) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects1 | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | ||

| Constant | 3.23 | .16 | 19.68 | 1.60 | .18 | 8.78 | .65 | .12 | 5.40 | ||

| PS | .17 | .04 | 4.44 | .17 | .03 | 5.66 | .22 | .02 | 11.57 | ||

| RE | - | - | - | .50 | .04 | 12.36 | .19 | .03 | 6.72 | ||

| PSE | - | - | - | - | - | - | .30 | .03 | 9.76 | ||

| F(1,381) = 19.68, p < .001, R2 = .05 |

F(2,380) = 113.55, p < .001, R2 = .37 |

F(3,379) = 212.35, p < .001, R2 = .63 |

|||||||||

| Total effects1 | |||||||||||

| Constant | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.25 | .10 | 21.96 | ||

| PS | - | - | - | - | - | - | .33 | .024 | 13.89 | ||

| F(1,381) = 193, p < .001, R2 = .34 |

|||||||||||

| Indirect Effects | Effect | BootSE | Boot-LLCI | Booot-BULCI | |||||||

| Total | .11 | .02 | .07 | .15 | |||||||

| Ind1 PS→RE→SC | .03 | .01 | .01 | .05 | |||||||

| Ind2 PS→PSE→SC | .05 | .01 | .03 | .08 | |||||||

| Ind3 PS→RE→PSE→SC | .02 | .01 | .01 | .04 | |||||||

| Contrast indirect effects | |||||||||||

| C1 (Ind1-Ind2) | -.02 | .02 | -.05 | .01 | |||||||

| C2 (Ind1-Ind3) | .01 | .01 | -.01 | .02 | |||||||

| C3 (Ind2–Ind3) | .03 | .01 | .01 | .05 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).