Submitted:

28 July 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Fundamental Issues

2.1.1. Terminology

2.1.2. Predicting Outcomes

2.2. The Challenge

2.2.1. Public perception

3. Broad Approaches

3.1. Deregulation

3.2. Impact Assessments

3.3. Voluntary Corporate Strategies

3.3.1. Implementation Strategies

3.3.2. Measuring Corporate Sustainability

3.3.3. Social Entrepreneurship

3.4. Regulations on Existing Activities

3.4.1. Heterogeneous Impacts

3.4.2. Heterogeneous Frameworks

3.4.3. Plastics and Packaging

3.5. Consumer Behavior

3.5.1. Green Marketing

3.5.2. Models of Green Purchase Behavior

3.5.3. Empirical Results

3.5.4. Consumers and Sustainable Cosmetics

3.5.5. Consumers and Sustainable Packaging

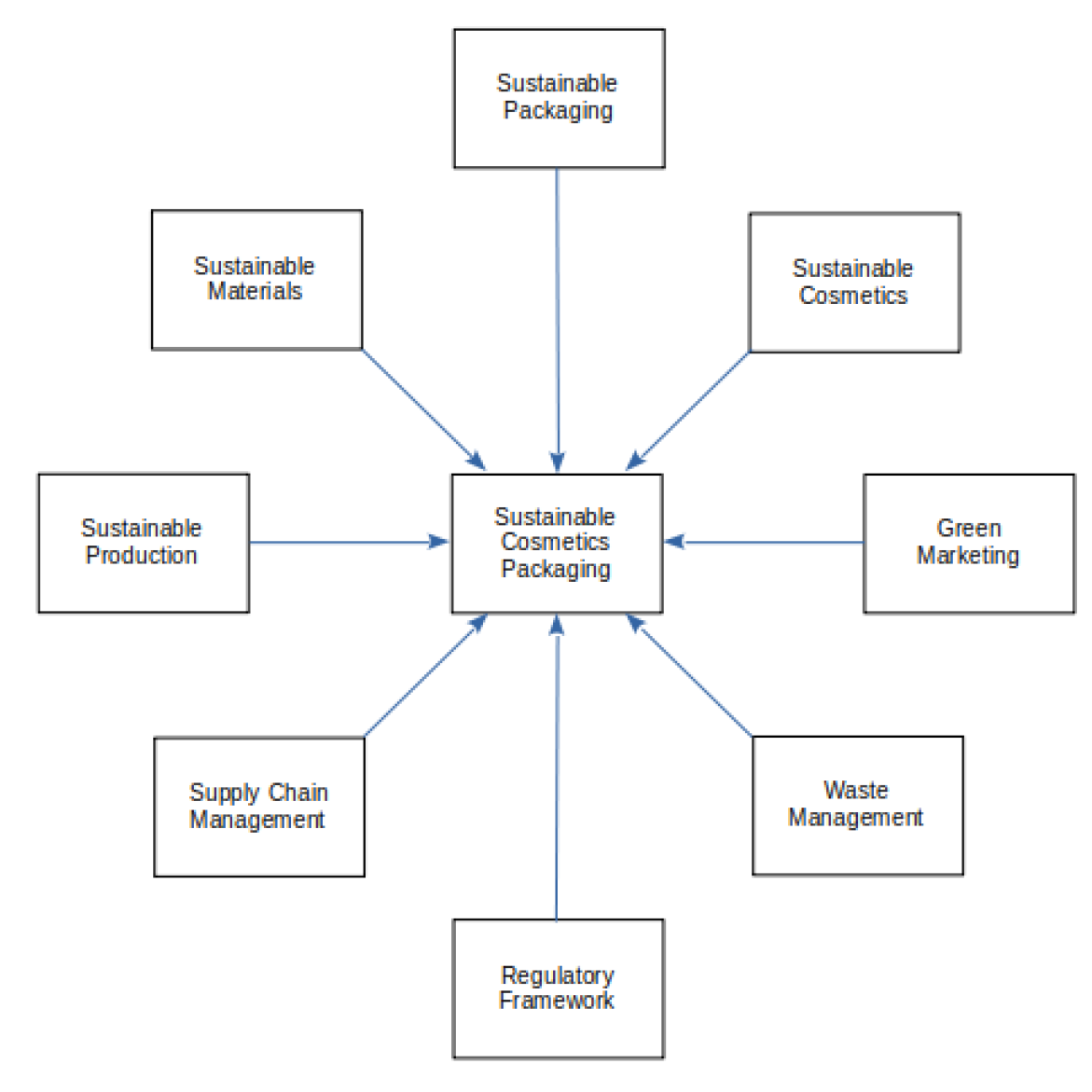

4. Sustainability Strategies

4.1. Sustainable Cosmetics

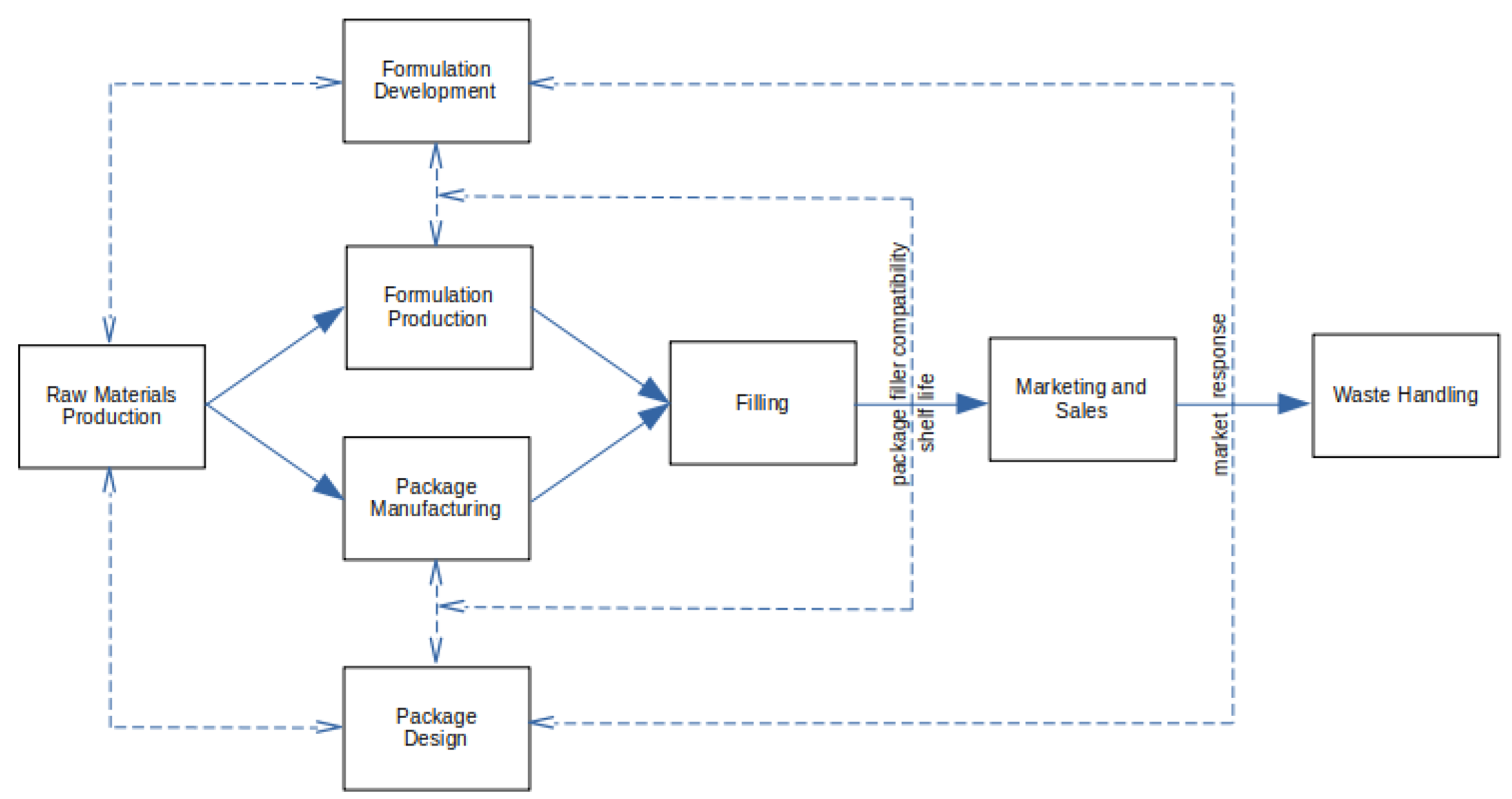

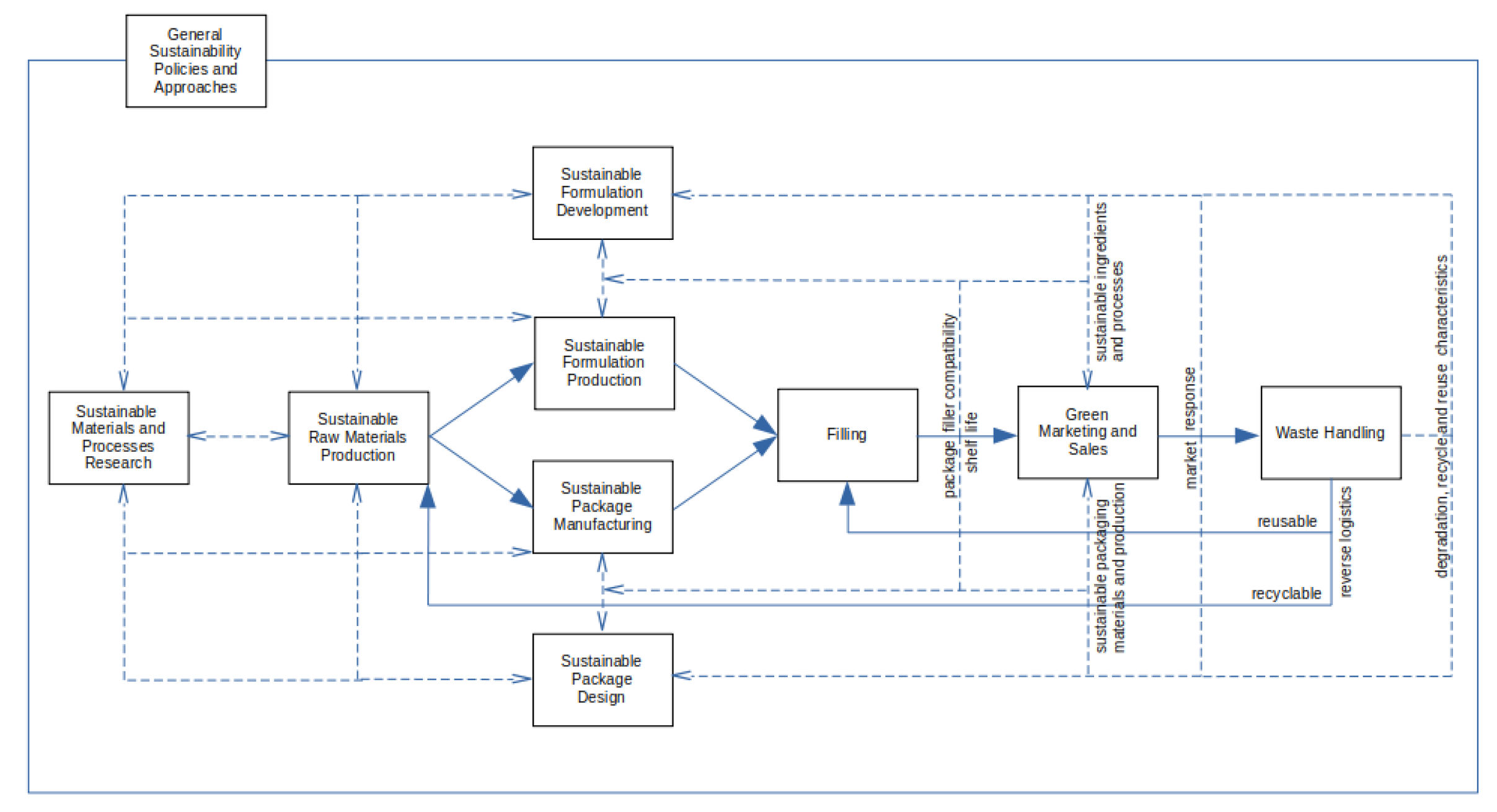

4.1.1. Green supply chain

4.1.2. Natural ingredients

4.1.3. Biopolymers

4.1.4. Processes and Health Safety

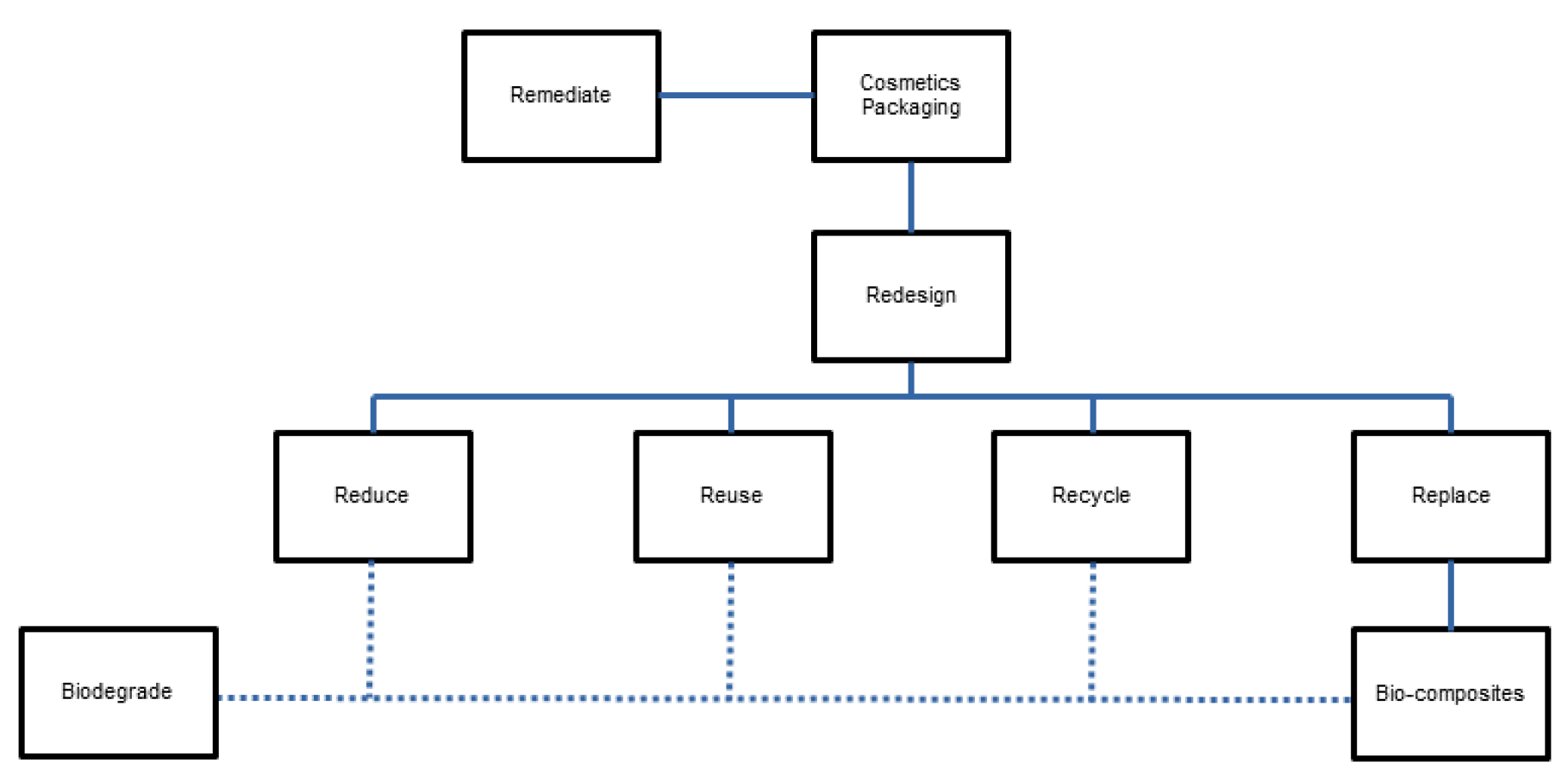

4.2. Sustainable Packaging

4.2.1. Plastic Packaging

Recycling

Reuse

Biocomposites

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Potential Pitfalls

-

attempting to sell products that may not necessarily help the environment

- –

- depending on local post-use handling and infrastructure

- –

- the sustainability criteria applied

- –

- and may also underperform and be overpriced

-

introduced in response to unreliable demand estimates

- –

- that may or may not materialize

- –

- based on models that may not be accurate

- –

- for consumers who may not trust or even understand the claims

-

potentially without complete knowledge of sustainability

- –

- of the manufacturing processes

- –

- or the economics of the business model

- for compliance with policies not necessarily fully-informed

-

in conjunction with heterogeneous supply-chain partners

- –

- each with their own values, expertise and business models

- –

- subject to different stakeholder demands and regulations

5.2. Desirable Characteristics

5.3. Research Program

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions-in-5-charts (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Kannan, S. Impact of Industrialization on Social Mobility in Puducherry. Man in India 2016, 96(4), 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Exploratory analysis of global cosmetics industry: major players, technology and market trends. Technovation 2005, 25, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; McDonagh, P. Producing Environmentally Acceptable Cosmetics? The Impact of Environmentalism on the United Kingdom Cosmetics and Toiletries Industry. Journal of Marketing Management 1992, 8, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, P.; Lohani, A.; Gagliardini, A.; Morganti, G.; Coltelli, M.-B. Active Ingredients and Carriers in Nutritional Eco-Cosmetics. Compounds 2023, 3, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubas, A.L.V.; Bianchet, R.T.; dos Reis, I.M.A.S.; Gouveia, I.C. Plastics and Microplastic in the Cosmetic Industry: Aggregating Sustainable Actions Aimed at Alignment and Interaction with UN Sustainable Development Goals. Polymers 2022, 14, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earth Overshoot Day is Coming Sooner and Sooner. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/15026/earth-overshoot-day-comes-sooner-every-year/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Mandelik, Y.; Dayan, T.; Feitelson, E. Issues and dilemmas in ecological scoping: scientific, procedural and economic perspectives. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2005, 23, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Past and future decline and extinction of species. Available online: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/biodiversity/decline-and-extinction/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Calculating Deforestation Figures for the Amazon. Available online: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/deforestation_calculations.html (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Montes, R.M.A.; Delapaz, G.V.; Oliquiano, J.I.D.R.; Pascasio, H.K.A.; Lugay, C.I.J.R.P. A Study on the Impact of Green Cosmetic, Personal Care Products, and their Packaging on Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior in Luzon, Philippines. In Proceedings of the 7th North American International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Orlando, Florida, USA, 12-14 June 2022; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Calero, C.; Godoy, V.; Queseda, L.; Martin-Lara, M.A. Green strategies for microplastics reduction. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2021, 28, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I.V.; Shaikh, V.A.E. A comprehensive review on assessment of plastic debris in aquatic environment and its prevalence in fishes and other aquatic animals in India. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 779, 146421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Farzadkia, M. Beach debris quantity and composition around the world: A bibliometric and systematic review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 178, 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, R.; Robin, R.S.; Purvaja, R.; Karthikeyan, V.; Subbareddy, B.; Balachandar, K.; Hariharan, G.; Ganguly, D.; Samuel, V.D.; Jinoj, T.P.S.; Ramesh, R. Microplastic pollution in fragile coastal ecosystems with special reference to the X-Press Pearl maritime disaster, southeast coast of India. Environmental Pollution 2022, 178, 119297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleel, R.; Valsan, G.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Warrier, A.K. Hidden problems in geological heritage sites: The microplastic issue on Saint Mary’s Island, India, Southeast Arabian Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2022, 182, 114043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Haider, A.; Ahmad, H.M.; Mohyuddin, A.; Aslam, H.M.U.; Nadeem, S.; Javed, M.; Othman, M.H.D.; Hog, H.H.; Chew, K.W. Source, occurrence, distribution, fate, and implications of microplastic pollutants in freshwater on environment: A critical review and way forward. Chemosphere 2023, 325, 138367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kye, H.; Kim, J.; Ju, S.; Lee, J.; Lim, C.; Yoon, Y. Microplastics in water systems: A review of their impacts on the environment and their potential hazards. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugilarasan, M.; Karthik, R.; Subbareddy, B.; Hariharan, G.; Anandavelu, I.; Jinoj, T.P.S.; Purvaja, R.; Ramesh, R. Anthropogenic marine litter: An approach to environmental quality for India’s southeastern Arabian Sea coast. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 866, 161363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Xiang, J.; Ko, J.H. Municipal plastic recycling at two areas in China and heavy metal leachability of plastic in municipal solid waste. Environmental Pollution 2020, 260, 114074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, C.J. Plastic pollution and potential solutions. Science Progress 2018, 101, 207–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.L.; Narayan, R. Reducing environmental plastic pollution by designing polymer materials for managed end-of-life. Nature Reviews Materials 2022, 7, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea. PlosOne 2014, 0111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Where the EU exports its waste. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/24716/main-destinations-for-eu-waste/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Plastic Waste Makers Index 2023. Available online: https://cdn.minderoo.org/content/uploads/2023/02/04205527/Plastic-Waste-Makers-Index-2023.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Stumpf, L.; Schoggl, J.-P.; Baumgartner, R.J. Circular plastics packaging – Prioritizing resources and capabilities along the supply chain. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 2023, 188, 122261. [Google Scholar]

- Explainer: Toxic Substances Control Act. Available online: https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/explainer-toxic-substances-control-act/1010187.article (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Bridges, J.W.; Greim, H.; van Leeuwen, K.; Stegmann, R.; Vermeire, T.; den Haan, K. Is the EU chemicals strategy for sustainability a green deal? Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 2023, 139, 105356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, N.; Bero, L.; Woodruff, T.J. The Devil they Knew: Chemical Documents Analysis of Industry Influence on PFAS Science. Annals of Global Health 2023, 89(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3M Resolves Claims by Public Water Suppliers, Supports Drinking Water Solutions for Vast Majority of Americans. Available online: https://investors.3m.com/news-events/press-releases/detail/1784/3m-resolves-claims-by-public-water-suppliers-supports (accessed on June 26 2023).

- Press Releases Related to PFAS. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/press-releases-related-pfas (accessed on June 26 2023).

- Cingano, F. Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth. In OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 163; OECD Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dabla-Norris, E.; Kochhar, K.; Suphaphiphat, N.; Ricka, F.; Tsounta, E. Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality: A Global Perspective. In IMF Staff Discussion Notes 15/13; International Monetary Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- For most, U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Bruton, G.; Sutter, C.; Lenz, A.-K. Economic inequality - Is entrepreneursihp the cause or the solution? A review and research agenda for emerging economies Journal of Business Venturing 2021, 36, 106095. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Lei, T.; Jia, L.; Yury, B.; Zhang, Z.; Du., Y.; Fang, Y.; Xing, B. Bioaccessible trace metals in lip cosmetics and their health risks to female consumers. Environmental Pollution 2018, 238, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Mehmood, S.; Iqbal, H.M.N. The Beast of Beauty: Environmental and Health Concerns of Toxic Compounds in Cosmetics. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.L.L.; Coleman, H.M.; Khan, S.J. Chemical contaminants in swimming pools: Occurrence, implications and control. Environment International 2015, 76, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A.; Gago-Ferrero, P.; Vazquez-Sune, E.; Carrera, J.; Pujades, E.; Diaz-Cruz, M.S.; Barcelo, D. Urban groundwater contamination by residues of UV filters. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2014, 271, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Han, X.; Li, G.; Tian, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, F.; Han, Y.; Yang, J. Occurrence, distribution and ecological risk of ultraviolet absorbents in water and sediment from Lake Chaohu and its inflowing rivers, China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2018, 164, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, C.; Magrini, G.A. Cosmetic Ingredients as Emerging Pollutants of Environmental and Health Concern. A Mini-Review Cosmetics 2017, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giokas, D.L.; Salvador, A.; Chisvert, A. UV filters: From sunscreens to human body and the environment. Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2007, 26, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Quilez, D.; Tovar-Sanchez, A. Are sunscreens a new environmental risk associated with coastal tourism. Environment International 2017, 83, 158–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaini, A.; Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J.; Hussin, N. I buy green products, do you. . .? The moderating effect of eWOM on green purchase behavior in Malaysian cosmetics industry. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing 2020, 14(1), 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.; Rego-Alvarez, L. Regulatory drivers in the last 20 years towards the use of in silico techniques as replacements to animal testing for cosmetic-related substances. Computational Toxicology 2020, 142, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ashokkumar, V.; Amobonye. A.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Sirohi, R.; Singh, V.; Flora, G.; Kumar, V.; Pillai, S.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M. K. Current research trends on cosmetic microplastic pollution and its impacts on the ecosystem: A review. Environmental Pollution 2023, 320, 121106.

- Anagnosti, L.; Varvaresou, A.; Pavlou, P.; Protopapa, E.; Carayanni, V. Worldwide actions against plastic pollution from microbeads and microplastics in cosmetics focusing on European policies. Has the issue been handled effectively? Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 162, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, P. Ethical Consumerism in The Cosmetics Industry: Measuring how Important Sustainability is to The Female Consumer. Bachelors Thesis, University of Twente, The Netherlands, 26 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grappe, C.G.; Lombart, C.; Louis, D.; Durif, F. Clean labeling: Is it about the presence of benefits or the absence of detriments? Consumer response to personal care claims Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 65, 102893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior: an Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and Pce. In NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 32; Menon, G., Rao, A.R., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research, 2005; pp. 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, S.; Hanifah, H.; Iqbal, Q. An Exploratory Study of Consumer Attitudes toward Green Cosmetics in the UK Market. Administrative Sciences 2018, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzan, G.; Cruceru, A.F.; Balaceanu, C.T.; Chivu, R.-G. Consumers’ Behavior Concerning Sustainable Packaging: An Exploratory Study on Romanian Consumers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioplastics innovation ’particularly poorly covered’ in cosmetics: Report. Available online: https://www.cosmeticsdesign-europe.com/Article/2020/04/27/Bioplastics-packaging-innovation-poor-in-cosmetics-finds-Clarivate-Analytics (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- When to Choose Biobased Packaging for Cosmetics - An Interview with Caroli Buitenhuis. Available online: https://formulabotanica.com/biobased-packaging-cosmetics/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Wandosell, G.; Parra-Merono, M.C.; Alcayde, A.; Banos, R. Green Packaging from Consumer and Business Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W. Double-edged sword effect of packaging: Antecedents and consumer consequences of a company’s green packaging design. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 406, 137037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, H.; Boons, F.; Bragd, A. Mapping the green product development field: engineering, policy and business perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 2002, 10, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluher, T.; Riedelsheimer, T.; Gogineni, D.; Klemichen, A.; Stark, R. Systematic Literature Review—Effects of PSS on Sustainability Based on Use Case Assessments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. The future of CSR: Towards transformative CSR, or CSR 2.0. In Research handbook on corporate social responsibility in context; Ortenblad, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2016; pp. 339–367. [Google Scholar]

- Boz, Z.; Kothonen, V.; Sand, C.K. Consumer Considerations for the Implementation of Sustainable Packaging: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntin, M.B.; Burke, M. F.; Hoaglin, M.C.; Blumenthal, D. The Benefits of Health Information Technology: A Review Of The Recent Literature Shows Predominantly Positive Results. Health Affairs 2011, 30(3), 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, S.; Dube, M. SomPack: If You Can’t Beat Them, Join Them? Ivey Publishing/ Harvard Business Case Collection, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, H.; van Beukering, P.; Broiwer, R. Business models and sustainable plastic management: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 258, 120967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alejandrino, C.; Mercante, I.T.; Bovea, M.D. Combining O-LCA and O-LCC to support circular economy strategies in organizations: Methodology and case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 336, 130365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglieri, F.N.; Salvador, R.; Romero-Hernandez, O.; Filho, E.E.; Piekarksi, C.M.; de Francisco, A.C.; Ometto, A.R. Strategic planning oriented to circular business models: A decision framework to promote sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 31, 3254–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Rocca, R.; Fumagalli, L.; Taisch, M. Enhancing the cosmetics industry sustainability through a renewed sustainable supplier selection model. Production & Manufacturing Research 2023, 11, 2161021. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, P.; Coltelli, M.B.; Signori, F.; Morganti, P.; Lazzeri, A. Cosmetic Packaging to Save the Environment: Future Perspectives. Cosmetics 2019, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenow, P.; Destler, E.; Springer, A. The Search for Suitable Packaging for Cosmetics – a Case Study. SOFW Journal 2022, 148, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Klitkou, A.; Bolwig, S.; Hansen, T.; Wessberg, N. The role of lock-in mechanisms in transition processes: The case of energy for road transport. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2015, 16, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, L.; Al Shawwa, H.; Nicolli, F.; Quaglietti, V. Towards sustainability: The Impact of Environmental Sustainability of Consumer Goods in the Italian Packaging Sector. Transnational Marketing Journal 2022, 10(2), 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Jager-Roschko, M.; Petersen, M. Advancing the circular economy through information sharing: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 369, 133210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M.; Dube, S. SomPack: succession planning gone wrong. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Elsamahy, T.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Li, F.; Kornaros, M.; Zuorro, A.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Bioplastic production in terms of life cycle assessment: A state-of-the-art review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayicki, Y.; Kazanoglu, Y.; Gozacan-Chase, N.; Lafci, C.; Batista, L. Assessing smart circular supply chain readiness and maturity level of small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Business Research 2022, 149, 375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Volcalelli, D. Green Marketing: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2df5d1d2-fac7-11e7-b8f5-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Henchion, H.M.; Shirsath, A.P. Developing and implementing a transdisciplinary framework for future pathways in the circular bioeconomy: The case of the red meat industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 380, 134845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Lavado, A.; Gimenez-Fernandez, E.M.; Vlaisavljevic, V.; Cabello-Medina, C. Cross-industry innovation: A systematic literature review. Technovation 2023, 124, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, P.; Everard, M.; Santillo, D.; Robert, H.-K. Reclaiming the Definition of Sustainability. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 2007, 13(1), 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E. The Circular Economy - A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollman, F. Corporate Social Responsibility, ESG, and Compliance. In The Cambridge Handbook of Compliance; van Rooij, B., Sokol, D.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, England, 2021; pp. 662–672. [Google Scholar]

- Saidani, M.; Yannou, B.; Leroy, Y.; Cluzel, F.; Kendall, A. A taxonomy of circular economy indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 207, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorn, A.; Lloyd, S.M.; Brander, M.; Matthews, H.D. Renewable energy certificates threaten the integrity of corporate science-based targets. Nature Climate Change 2022, 12, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiano, A.N.; Drake, M.A. Sustainability: Different perspectives, inherent conflict. Journal of Dairy Science 2021, 103(11), 11386–11400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.B.Y. Drivers of divergent industry and consumer food waste behaviors: The case of reclosable and resealable packaging. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 412, 137417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasza, G.; Veflen, N.; Scohlderer, J.; Munter, L.; Fekete, L.; Csenki, E.Z.; Dorko, A.; Szakos, D.; Iszo, T. Conflicting Issues of Sustainable Consumption and Food Safety: Risky Consumer Behaviors in Reducing Food Waste and Plastic Packaging. Foods 2022, 11, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, S.; Jorge, J.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. A step forward on sustainability in the cosmetics industry: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 225, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F.; Wischnevsky, J.D. Research on innovation in organizations: Distinguishing innovation-generating from innovation-adopting organizations. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 2006, 23, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldaschl, M. Why Innovation Theories Make no Sense. Papers and Preprints of the Department of Innovation Research and Sustainable Resource Management, Chemnitz University of Technology 2010, 9/2010.

- Suchek, N.; Fernandes, C.I.; Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; Sjorgren, H. Innovation and the circular economy: A systematic literature review. Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intezari, A.; Taskin, N.; Pauleen, D.J. Looking beyond knowledge sharing: an integrative approach to knowledge management culture. Journal of Knowledge Management 2017, 21(2), 492–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Torres, G.C.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Maldonado-Guzman, G.; Kumar, V.; Rocha-Lona, L.; Cherrafi, A. Knowledge management for sustainability in operations. Production Planning & Control 2019, 30, 813–826. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, V.W.B.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Knowledge management in the context of sustainability: Literature review and opportunities for future research. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 229, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguankaew, P.; Ractham, V.V. Bibliometric Review of Research on Knowledge Management and Sustainability, 1994–2018. Sustainability 2019, 11(16), 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.L.-H.; Lin, T.-C. The role of organizational culture in the knowledge management process. Journal of Knowledge Management 2015, 19, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matic, D.; Cabrilo, S.; Grubic-Nesic, L.; Milic, B. Investigating the impact of organizational climate, motivationaldrivers, and empowering leadership on knowledge sharing. Knowledge Management Research and Practice 2017, 15, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-C.; Chang, H.-T.; Chi, H.-R.; Chen, M.-H.; Agnikpe, C.; Deng, L.-L. How do established firms improve radical innovation performance? The organizational capabilities view Technovation 2012, 32, 441–451. [Google Scholar]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Ahenkorah, E.; Afum, E.; Agyemang, A.N.; Agnikpe, C.; Rogers, F. Examining the influence of internal green supply chain practices, green human resource management and supply chain environmental cooperation on firm performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 2020, 25, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, D.; Rauter, R.; Fleib, E.; Stern, T. Mind the gap: Towards a systematic circular economy encouragement of small and medium-sized companies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 98, 126696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Huang, H.-L. Knowledge management fit and its implications for business performance: A profile deviation analysis. Knowledge-Based Systems 2012, 27, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.G.; Min, J. Employees’ online knowledge sharing: the effects of person-environment fit. Journal of Knowledge Management 2017, 21, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehn, U.; Montalvo, C. Knowledge transfer dynamics and innovation: Behaviour, interactions and aggregated outcomes. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 171 (Suppl.), S56–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Dube, M. Knowledge management, innovation, and competitive advantage: is the relationship in the eye of the beholder? Knowledge Management Research and Practice 2018, 16(3), 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Carvalho, M.; Pinto, C. The Preservation of Memory and the Management of Information as a Step towards Sustainable Development. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development 2023, 19, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T. Product Development Implications of Sustainable Consumption. The Design Journal 2000, 3, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green marketing: legend, myth, farce or prophesy? Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.; Barros, R.B.G. Natural and Organic Cosmetics: Definition and Concepts. Journal of Cosmetology & Tribology 2020, 6, 503–520. [Google Scholar]

- Bozza, A.; Campi, C. ;Garelli, S; Ugazio, E. ; Battagila, L. Current regulatory and market frameworks in green cosmetics: The role of certification Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2022, 30, 100851. [Google Scholar]

- Filiciotto, L.; Rothenberg, G. Biodegradable Plastics: Standards, Policies, and Impacts. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guntzburger, Y.; Peignier, I.; de Marcellis-Warin, N. The consumers’ (mis)perceptions of ecolabels’ regulatory schemes for food products: insights from Canada. British Food Journal 2021, 124(11), 3497–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P.; Caferra, R.; D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imerbt, E.; Morone, A. Consumer willingness to pay for bio-based products: Do certifications matter? International Journal of Production Economics 2021, 240, 108248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg, N.; Fogarassy, C. Green Consumer Behavior in the Cosmetics Market Resources 2019, 8, 137. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2019, 30, 100851. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M.; Matos, A. ; Couras, A; Marto, J. ; Ribeiro, H. Overview of Cosmetic Regulatory Frameworks around the World Cosmetics 2022, 9, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Kassaye, W.W. Green Dilemma. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 2001, 19/6, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, J.; Aramaki, T.; Hanaki, K. Evaluating source separation of plastic waste using conjoint analysis. Waste Management 2008, 28, 2393–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansink, E.; Wijk, L.; Zuidemeer, F. No clue about bioplastics. Ecological Economics 2022, 191, 107245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkgraaf, E.; Gradus, R. Post-collection Separation of Plastic Waste: Better for the Environment and Lower Collection Costs? Environmental and Resource Economics 2020, 77, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubin, S.; Beaugrand, J.; Berteloot, M.; Boutrou, R.; Buche, P.; Gontard, N.; Guillard, V. Plastics in a circular economy: Mitigating the ambiguity of widely-used terms from stakeholders consultation. Environmental Science and Policy 2022, 134, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a Knowledge-based Theory of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spender, J.-C. Making Knowledge the Basis of a Dynamic Theory of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal 1996, 17, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bom, S.; Gouveia, L.P.; Pinto, P.; Martins, A.M.; Ribeiro, H.M.; Marto, J. A mathematical modeling strategy to predict the spreading behavior on skin of sustainable alternatives to personal care emollients. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 205, 111865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, G.S.; Fameau, A.-L.; Leonforte, F.; Greaves, A.J. Surface science of cosmetic substrates, cleansing actives and formulations. Advances in Colloids and Interface Science 2021, 290, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sastre, R.M.; de Paula, I.C.; Echeveste, M.E.S.; Greaves, A.J. A Systematic Literature Review on Packaging Sustainability: Contents, Opportunities, and Guidelines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, F.; Gomez, J.M.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.; Alvarez, O. Integrated design of emulsified cosmetic products: A review. Impact Assessment 1982, 1, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistritz, F.L.; Murdock, S.H.; Chase, A.R. Socioeconomic Impact Assessment Models: Review and Evaluation. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2020, 1, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Elk, R.; Mot, E.; Franses, P.H. Modeling healthcare expenditures: overview of the literature and evidence from a panel time-series model. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 2010, 10, 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G., Jr. Some Remarks on Impact Assessment. Impact Assessment, 1, 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.; Dube, M. Basics First, 1st ed.; Publisher: Iff Books Winchester, UK, 2017; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin, M. The Wrong Answer Faster: The Inside Story of Making the Machine that Trades Trillions, 1st ed.; Publisher: Wiley New Jersey, US, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F.; French, K.R. Choosing Factors. Journal of Financial Economics 2018, 128, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzmark, S.M.; Shue, K. Counterproductive sustainable investing: The impact elasticity of brown and green firms; Working Paper; Boston College, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Cosic, A.; Iraldo, F. Determining factors of curtailment and purchasing energy related behaviours. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 112, 3810–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paille, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giant Wind Turbines Keep Mysteriously Falling Over. This Shouldn’t Be Happening. Available online: https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/infrastructure/a42622565/wind-turbines-falling-over/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Andersen, I.; Guven, I.; Madenci, E.; Gustaffson, G. The Necessity of Reexamining Previous Life Prediction Analyses of Solder Joints in Electronic Packages. IEEE Transactions on Components and Packaging Technology 2000, 23(3), 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M.; Kundu, T. Yield Function for Elastoviscoplastic Solder Modeling. ASME Journal of Electronic Packaging 2005, 127(2), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M.; Kundu, T. Closure to Discussion of Yield Function for Elastoviscoplastic Solder Modeling. ASME Journal of Electronic Packaging 2011, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M.; Dube, S. Criticality of Robustness Checks for Complex Simulations and Modeling. Information - An International Interdisciplinary Journal 2013, 16, 7917–7940. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, F.J. Assembly Automation: A Management Handbook, 2nd ed.; Industrial Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nettleton, D.F.; Fernandez-Avila, C.; Sanchez-Esteva, S.; Verstichel., S.; Coltelli, M.B.; Marti-Soler, H.; Aliotta, L.; Gigante, V. Biodegradation Prediction and Modelling for Decision Support. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Simulation and Modeling Methodologies, Technologies and Applications, Lisbon, Portugal, July 2022; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, L.M. Uncertainty and Climate Change. Statistical Science 2003, 18(4), 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, T.G. Atmospheric circulation as a source of uncertainty in climate change projections. Nature Geoscience 2014, 7, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, O. Advances and challenges in climate modeling. Climatic Change 2022, 170, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noto, L.V.; Cipolla, G.; Pumo, D.; Francipane, A. Climate Change in the Mediterranean Basin (Part II): A Review of Challenges and Uncertainties in Climate Change Modeling and Impact Analyses. Water Resources Management 2023, 37, 2307–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, A.; Ray, P.; Wi, S.; Folch, C.; Ubierna, M.; Karki, P. Climate change and the hydropower sector: A global review. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2022, 13, e757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Serbin, S.P.; Way, D.A. Reducing model uncertainty of climate change impacts on high latitude carbon assimilation. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 1222–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legates, D.R.; Davis, R.E. The continuing search for an anthropogenic climate change signal: Limitations of correlation-based approaches. Geophysical Research Letters 1997, 24(18), 2319–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.; van Geel, B. Holocene Climate Change and the Evidence for Solar and other Forcings. In Natural Climate Variability and Global Warming: A Holocene Perspective; Battarbee, R.W., Binney, H.A., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2008; pp. 138–162. [Google Scholar]

- Herndon, J.M. Evidence of Variable Earth-heat Production, Global Non-anthropogenic Climate Change, and Geoengineered Global Warming and Polar Melting. Journal of Geography, Environment and Earth Science International 2017, 2017, JGEESI.32220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, F. Solar and Anthropogenic Influences on Climate: Regression Analysis and Tentative Predictions. Climate 2021, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrable, K.; Chabot, G.; French, C. World Atmospheric CO2, Its 14C Specific Activity, Non-fossil Component, Anthropogenic Fossil Component, and Emissions (1750–2018). Health Physics 2022, 122(2), 391–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kleef, E.; Dagevos, H. The Growing Role of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Profile Labeling: A Consumer Perspective on Key Issues and Controversies. Food Science and Nutrition 2015, 55, 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Donini, L.M.; Berry, E.M.; Folkvord, F.; Jansen, L.; Leroy, F.; Simsek, O.; Fava, F.; Gobetti, M.; Lenzi, A. Front-of-pack labels: “Directive” versus “informative” approaches. Nutrition 2023, 105, 111861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguenaou, H.; Babio, N.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C.; Jones, A.; Karpetas, G.; Kelly, B.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; et al. Comment on Muzzioli et al. Are Front-of-Pack Labels a Health Policy Tool? Nutrients 2022, 14, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzioli, L.; Penzavecchia, C.; Donini, L.M.; Pinto, A. Reply to Aguenaou et al. Comment on “Muzzioli et al. Are Front-of-Pack Labels a Health Policy Tool? Nutrients 2022, 14, 771”. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiene, M.; Scarpa, R.; Longo, A.; Hutchinson, G. Types of front of pack food labels: Do obese consumers care? Evidence from Northern Ireland. Food Policy 2018, 80, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C. G.; Burke, P.F.; Waller, D.S.; Wei, E. The impact of front-of-pack marketing attributes versus nutrition and health information on parents’ food choices. Appetite 2017, 116, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhne, S.J.; Reijnen, E.; Granja, G.; Hansen, R.S. Labels Affect Food Choices, but in What Ways? Nutrients 2022, 14, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzzioli, L.; Penzavecchia, C.; Donini, L.M.; Pinto, A. Are Front-of-Pack Labels a Health Policy Tool? Nutrients 2022, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrat, P.; Mejean, C.; Julia, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.; Hercberg, S.; Peneau, S. Effectiveness of Front-Of-Pack Nutrition Labels in French Adults: Results from the NutriNet-Santé Cohort Study. PloS ONE 2015, 10(10), e0140898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzullo, P.; Cairella, G.; Sofi, F.; Erba, D.; Campanozzi, A. et al. “Front-of-pack” nutrition labeling. Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases 2021, 31, 2989–2992. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, M.; Guetterman, T.; Volschenk, J.; Kidd, M.; Joubert, E. Healthy or Not Healthy? A Mixed-Methods Approach to Evaluate Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels as a Tool to Guide Consumers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, L.J.J.; van Emmerik, T.; van der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Science Advances 2021, 7, eaaz5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kash, D.E. Impact Assessment Premises - Right and Wrong. Impact Assessment 1982, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, E.W. Anticipating Technologically-Derived Risk. Impact Assessment 1982, 1, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrami, M.; Orzes, G.; Sarkis, J.; Sartor, M. Industry 4.0 and sustainability: Towards conceptualization and theory. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 312, 127733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, A.B.T.; de Oliveira, K.B.; Espuny, M.; da Motta Reis, J.S.; Oliveira, O.J. Business transformation through sustainability based on Industry 4.0. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Choi, T.-M.; Latan, J. ‘Better together’: Evidence on the joint adoption of circular economy and industry 4.0 technologies. International Journal of Production Economics 2022, 252, 108581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.S.; Ahmad, M.O.; Majava, J. Industry 4.0 and sustainable development: A systematic mapping of triple bottom line, Circular Economy and Sustainable Business Models perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 297, 126655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilian, B.; Sarkis, J.; Lewis, K.; Behdad, S. Blockchain for the future of sustainable supply chain management in Industry 4.0. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 163, 105064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, E.; Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S. Circular supply chains in the era of industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Computer & Industrial Engineering 2022, 170, 108268. [Google Scholar]

- Behl, A.; Singh, R.; Pereira, V.; Laker, B. Analysis of Industry 4.0 and circular economy enablers: A step towards resilient sustainable operations management. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 2023, 189, 122363. [Google Scholar]

- Touriki, F.E.; Benkhati, I.; Kample, S.S.; Belhadi, A.; El fezazi, S. An integrated smart, green, resilient, and lean manufacturing framework: A literature review and future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 319, 128691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniza, R.; Chen, W.-H.; Petrissans, A.; Hoang, A.T.; Ashokkumar, V.; Petrissans, M. A review of biowaste remediation and valorization for environmental sustainability: Artificial intelligence approach. Environmental Pollution 2023, 324, 121363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B. Pharma Industry 4.0: Literature review and research opportunities in sustainable pharmaceutical supply chains. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2018, 119, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haba, H.F.; Bredillet, C.; Dastane, O. Pharma Green consumer research: Trends and way forward based on bibliometric analysis. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 2023, 8, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Urban, M.A.; Wojcik, D. Alternative ESG Ratings: How Technological Innovation Is Reshaping Sustainable Investment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntingford, C.; Jeffers, E.S.; Bonsall, M.B.; Christensen, H.M.; Lees, T.; Yang, H. Machine learning and artificial intelligence to aid climate change research and preparedness. Environmental Research Letters 2010, 14, 124007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahoud, A.; Fezari, M.; Aldahoud, A. Machine Learning in Renewable Energy Application: Intelligence System for Solar Panel Cleaning. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development 2023, 19, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschang, F.T.; Almirall, E. Artificial intelligence as augmenting automation: Implications for employment. Academy of Management Perspectives 2021, 35(4), 642–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Analysis of the Impact of Artificial Intelligence Development on Employment. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application IEEE (2020); pp. 324–327.

- Padilla-Rivera, A.; Russo-Garido, S.; Merveille, N. Addressing the Social Aspects of a Circular Economy: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.; Dube, M.; Turan, A. Information technology in Turkey: Creating high-skill jobs along with more unemployed highly-educated workers? Telecommunications Policy 2015, 38(10), 811–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. H; Jones, R.A.; Haley, B.; Kwok, G.; Hargreaves, J.; Farbes, J.; Torn, M. S. Carbon-Neutral Pathways for the United States. AGU Advances 2021, 2, e2020AV000284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renne, D. S. Progress, opportunities and challenges of achieving net-zero emissions and 100% renewables. Solar Compass 2022, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesfeld, P.; Cherry, C.R. Lead emissions from solar photovoltaic energy systems in China and India. Energy Policy 2011, 39(9), 4939–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H. Cost-benefit analysis of waste photovoltaic module recycling in China. Waste Management 2020, 118, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goe, M.; Gaustad, G. Strengthening the case for recycling photovoltaics: An energy payback analysis. Applied Energy 2014, 120, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, A.; Geyer, R. Photovoltaic waste assessment in Mexico. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2017, 127, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California went big on rooftop solar. Now that’s a problem for landfills. Available online: https://news.yahoo.com/california-went-big-rooftop-solar-120043034.html (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Bassi, S.A.; Boldrin, A.; Faraca, G.; Astrup, T.F. Extended producer responsibility: How to unlock the environmental and economic potential of plastic packaging waste? Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2020, 162, 105030. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle, A.; Walker, T.R. Implementation of harmonized Extended Producer Responsibility strategies to incentivize recovery of single-use plastic packaging waste in Canada. Waste Management 2020, 110, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Inadequacy of Wind Power. Available online: https://www.thegwpf.org/content/uploads/2023/03/Allison-Wind-energy.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Michaelides, E.E. Primary Energy Use and Environmental Effects of Electric Vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2021, 12(3), 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapper, A.; Unrau, C.; Killoh, S. Social mobilization against large hydroelectric dams: A comparison of Ethiopia, Brazil and Panama. Sustainable Development 2020, 28, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, B.A.; Rade, I. Metal resource constraints for electric-vehicle batteries. Transportation Research Part D 2001, 6, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunda, R.B. Potential environmental impacts of lithium mining. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 2020, 38, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Zaimes, G.G.; Hubler, B.J.; Wang, S.; Khanna, V. Environmental Life Cycle Perspective on Rare Earth Oxide Production. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering 2015, 3(2), 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billionaires are funding a massive treasure hunt in Greenland as ice vanishes. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/08/08/world/greenland-melting-mineral-mining-climate/index.html (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Rabaia, M.K.H.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Elsaid, K.; Chae, K.-J.; Wilberforce, T.; Olabi, A.G. Environmental impacts of solar energy systems: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 754, 141989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, L., Cleaver, T., Rajaeifar, M. A., Nguyen-Tien, V., Elliott, R. J. R.; Heidrich, O.; Kendrick, E.; Edge, J.S.; Offer, G. Financial viability of electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycling. iScience 2021, 24, 102787. [CrossRef]

- Despiesse, M.; Kishita, Y.; Nakano, M.; Barwood, M. Towards a circular economy for end-of-life vehicles: A comparative study UK - Japan. Procedia CIRP 29, the 22nd CIRP conference on Life Cycle Engineering; 2015; pp. 668–673. [Google Scholar]

- Skeete, J.-P.; Wells, P.; Dong, X.; Heidrich, O.; Harper, G. Beyond the EVent horizon: Battery waste, recycling and substainability in the United Kingdom electric vehicle transition. Energy Research & Social Science 2020, 69, 101581. [Google Scholar]

- Amberg, N.; Magda, R. ; Environmental Pollution and Sustainability or the Impact of the Environmentally Conscious Measures of International Cosmetic Companies on Purchashing Organic Cosmetics. Visegrad Journal of Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development 2018, 7(1), 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Dimitropoulos, A.; Farrow, K.; Queslati, W. Non-exhaust Particulate Emissions from Road Transport; OECD: OECD, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, K.; Lin, N.; Xian, S.; Chester, M. V. Can we evacuate from hurricanes with electric vehicles? Transportation Research Part D 2020, 86, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.; Awwad, M. A. The Use of Electric Cars in Short-Notice Evacuations: A Case Study of California’s Natural Disasters. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Monterrey, Mexico, 3-5 Nov 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhan, F.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z. Effect of Chinese Corporate Average Fuel Consumption and New Energy Vehicle Dual-Credit Regulation on Passenger Cars Average Fuel Consumption Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Biodegradable Plastics and Marine Litter. Misconceptions, concerns and impacts on marine environments.; United Nations Environment Program: Nairobi Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kardgar, A. K; Ghosh, D.; Sturve, J.; Agarwal, S.; Almroth, B.C. Chronic poly(L-lactide) (PLA)- microplastic ingestion affects social behavior of juvenile European perch (Perca fluviatilis). Science of the Total Environment 2023, 88, 163425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lab-Grown Meat’s Carbon Footprint Potentially Worse Than Retail Beef. Available online: https://www.ucdavis.edu/food/news/lab-grown-meat-carbon-footprint-worse-beef (accessed on July 15 2023).

- Herrmann, C.; Rhein, S.; Srater, K.F. Consumers’ sustainability-related perception of and willingness-to-pay for food packaging alternatives. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2022, 181, 106216. [Google Scholar]

- The future of gas in Europe: Review of recent studies on the future of Gas, CEPS Research Report No. 2019/03. Available online: https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/RR2019-03_Future-of-gas-in-Europe.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Global oil and gas investment will be 30% below pre-Covid level: ONGC. Available online: https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/global-oil-and-gas-investment-will-be-30-below-pre-covid-level-ongc-121092400690_1.html (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- The Role of Natural Gas in Europe Towards 2050, NTNU Energy Transition Policy Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.ntnu.edu/documents/1276062818/1283878281/Natural+Gas+in+Europe.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Coal power’s sharp rebound is taking it to a new record in 2021, threatening net zero goals, Coal 2021 Press Release, International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org/news/coal-power-s-sharp-rebound-is-taking-it-to-a-new-record-in-2021-threatening-net-zero-goals (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- German Emissions From Electricity Rose 25% In First Half Of 2021 Due To The Lack Of Wind Power, Not Willpower. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelshellenberger/2021/07/28/german-emissions-from-electricity-rose-25-in-first-half-of-2021-due-to-the-lack-of-wind-power-not-willpower/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Taylor, R.L.C. Bag leakage: The effect of disposable carryout bag regulations on unregulated bags. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 2019, 93, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.K.; Woodward, R.T. Spillover Effects of Grocery Bag Legislation: Evidence of Bag Bans and Bag Fees. Environmental and Resource Economics 2022, 81, 711–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2023 Reports 1 to 5 of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada. Available online: https://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_cesd_202304_05_e_44243.html (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Williams, R.; Banner, J.; Knowles, I.; Dube, M.; Natishan, M.; Pecht, M. An Investigation of ’Cannot Duplicate’ Failures. Quality and Reliability Engineering International 1998, 14(5), 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishongh, T.J.; Dube, M.; Pecht, M.; Wyler, J. Failure Analysis of Liquid Crystal Displays Due to Indium Tin Oxide Breakdown. ASME Journal of Electronic Packaging 1999, 121(2), 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecht, M.; Dube, M.; Natishan, M.; Williams, J.; Banner, J.; Knowles, I. Evaluation of Built-In Test. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronics Systems 2001, 37(1), 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Elusive Green Consumer. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/07/the-elusive-green-consumer (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Bratt, C. Consumers’ Environmental Behavior Generalized, Sector-Based, or Compensatory? Environment and Behavior 1999, 31, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Are oxo-biodegradable plastics bad for the environment? Available online: https://www.packaging-gateway.com/features/are-oxo-biodegradable-plastics-bad-for-the-environment/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Roy, S. Development, Environment and Poverty: Some Issues for Discussion. Economic & Political Weekly 1996, 31, PE29–PE41. [Google Scholar]

- COP26: Did India betray vulnerable nations? Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-59286790 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- What it will cost to get to net-zero. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/overview/in-the-news/what-it-will-cost-to-get-to-net-zero (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Stopping Global Warming Will Cost $50 Trillion: Morgan Stanley Report. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sergeiklebnikov/2019/10/24/stopping-global-warming-will-cost-50-trillion-morgan-stanley-report/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- What’s the cost of net zero? Available online: https://obr.uk/frs/fiscal-risks-report-july-2021/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Fiscal risks report – July 2021. Available online: https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/whats-the-cost-of-net-zero-2/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Claydon, J. A new direction for CSR: the shortcomings of previous CSR models and the rationale for a new model. Social Responsibility Journal 2011, 7(3), 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A. Sustainability improvement in luxury packaging: a case study in Giorgio Armani and Helena Rubinstein brands. Masters Thesis, Aalto University, Bordeaux, France, 20 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, J.R.D. Thoughtful Packaging: How Inner Motivations Can Influence the Purchase Intention for Green Packaged Cosmetics. Masters Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, H.B.; Broekaert, C.; Verline, S.; Macharis, S. Sharing is caring: How non-financial incentives drive sustainable e-commerce delivery. Transportation Research Part D 2021, 93, 102794. [Google Scholar]

- Escursell, S.; Llorach-Massana, P.; Roncero, M. B. Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 280, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmi, A.; Komaladewi, R.; Sarasi, V.; Yolanda, L. Characterizing Young Consumer Online Shopping Style: Indonesian Evidence. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopot, K.; Reed, J. Shopping for beauty: The influence of the pandemic on body appreciation, conceptions of beauty, and online shopping behaviour. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 2023, 14, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidhar, S.; Naresh, N.R.; Sharmila, A.; Shwetha, B.V.; Ramesh, S. Consumer Consideration for Herbal Cosmetic Products with respect to Present Scenario. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results 2023, 14, 2594–2601. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.C.; Sharon, E. The Volkswagen emissions scandal and its aftermath. GBOE 2019, 38, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabla-Norris, E.; Helbling, T.; Khalid, S., Khan; H., Magistretti; G.; Sollaci, A.; Srinivasan, S. Public Perceptions of Climate Mitigation Policies: Evidence from Cross-Country Surveys. In IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN2023/002; International Monetary Fund, 2023.

- Bago, B.; Rand, D.G.; Pennycook, G. Reasoning about climate change. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frases, B.C.; Harman, R.; Nunn, P.D. ; Associations of locus of control, information processing style and anti-reflexivity with climate change scepticism in an Australian sample. Public Understanding of Science 2023, 32(3), 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenther, L.; Jorges, S.; Mahl, D.; Bruggemann, M. Framing as a Bridging Concept for Climate Change Communication: A Systematic Review Based on 25 Years of Literature. Communication Research 2023, 009365022211371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirani, M.R.; Kowsari, E.; Termourian, T.; Ramakrishna, S. Environmental impact of increased soap consumption during COVID-19 pandemic: Biodegradable soap production and sustainable packaging. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 796, 149013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeed, A.; Rahman, M.H; Bundschuh, J.; Herath, I.; Ahmed, F.; Bhattacharya, P.; Tariz, M. R.; Rahman, F.; Joy, M.T.I.; Abid, M.T.; Saha, N.; Hasan, M. T. Handwashing with soap: A concern for overuse of water amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. Groundwater for Sustainable Development 2021, 13, 100561.

- Teymoorian, T.; Teymourian, T.; Kowsari, E.; Ramakrishna, S. Direct and indirect effects of SARS-CoV-2 on wastewater treatment. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2021, 42, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Alam, I.; Mahbub, M.S. Plastic pollution during COVID-19: Plastic waste directives and its long-term impact on the environment. Environmental Advances 2021, 5, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, X.; Ashton, W.S.; Dentchey, N. Addressing resources and waste management challenges imposed by COVID-19: An entrepreneurship perspective. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2020, 162m, 105058. [Google Scholar]

- Tetlow, M.F.; Hanusch, M. Strategic Environmental Assessment: The State of the Art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2012, 30(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sri Lanka faces ’man-made’ food crisis as farmers stop planting. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/18/a-food-crisis-looms-in-sri-lanka-as-farmers-give-up-on-planting (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Emotion and pain’ as Dutch farmers fight back against huge cuts to livestock. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jul/21/emotion-and-pain-as-dutch-farmers-fight-back-against-huge-cuts-to-livestock (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Don’t Pay UK: Campaign to boycott payment of energy bills gathers pace. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2022/08/04/dont-pay-uk-campaign-to-boycott-payment-of-energy-bills-gathers-pace (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- The Tricky Politics of Anti-ESG Investing. Available online: https://www.crainscleveland.com/opinion/opinion-tricky-politics-anti-esg-investing (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Update Corporate Governance and ESG Policies and Priorities for 2022. Available online: https://www.gibsondunn.com/blackrock-vanguard-and-state-street-update-corporate-governance-and-esg-policies-and-priorities-for-2022/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- BlackRock ditches green activism over Russia fears. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2022/05/11/blackrock-ditches-green-activism-russia-energy-fears/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- An update on Vanguard’s engagement with the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative. Available online: https://corporate.vanguard.com/content/corporatesite/us/en/corp/articles/update-on-nzam-engagement.html (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- A resolution directing an update to the investment policy statement and proxy voting policies for the Florida retirement system defined benefit pension plan, and directing the organization and execution of an internal review. Available online: https://www.flgov.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ESG-Resolution-Final.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Purchasing: Divestment Stature List. Available online: https://comptroller.texas.gov/purchasing/publications/divestment.php (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Sweden abandons 100% renewable energy goal. Available online: https://scandasia.com/sweden-abandons-100-renewable-energy-goal/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- ESG Not Making Waves with American Public. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/506171/esg-not-making-waves-american-public.aspx (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Exxon Mobil Corporation Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Available online: https://ir.exxonmobil.com/static-files/da018d10-fb85-4eb9-9251-d2e04f1923d5 (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Lloyd’s becomes the 10th major player to mark its exit from NZIA. Available online: https://www.reinsurancene.ws/lloyds-becomes-the-10th-major-player-to-mark-its-exit-from-nzia/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Arnold, D. Market Democracy: Land of Opportunity? Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society 2014, 26, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, C. Why not Marx? Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society 2014, 26, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourevitch, A. Welcome to the Dark Side: A Classical-Liberal Argument for Economic Democracy. Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society 2014, 26, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, P.; Morganti, G.; Memic, A.; Coltelli, M.B.; Chen, H.-D. The New Renaissance of Beauty and Wellness Through the Green Economy. Latest Trends in Textile and Fashion Design 2021, 4(2), 290–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Audi, M. The Impact of Income Inequality, Environmental Degradation and Globalization on Life Expectancy in Pakistan: An Empirical Analysis. International Journal of Economics and Empirical Research 2016, 4(4), 182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Asghar, M.M.; Zaidi, S.A.H.; Wang, B. Dynamic linkages among CO2 emissions, health expenditures, and economic growth: empirical evidence from Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 15285–15299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.Y.; Ajide, K.B.; Isola, W.A. Environmental quality and health expenditure in ECOWAS. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2020, 22, 5105–5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DDMA allows standing passengers in Delhi Metro trains, buses to tackle air pollution. Available online: https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/ddma-allows-standing-passengers-in-delhi-metro-buses-to-tackle-pollution-121112000908_1.html (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Soaring pollution has Delhi considering full weekend lockdown. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/nov/16/soaring-pollution-has-delhi-considering-full-weekend-lockdown (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Indian officials order Coca-Cola plant to close for using too much water. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/18/indian-officals-coca-cola-plant-water-mehdiganj (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Kahuthu, A. Economic growth and environmental degradation in a global context. Environment, Development, and Sustainability 2006, 8, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Ali, I.; Kousar, S.; Ahmed, S. The environmental impact of industrialization and foreign direct investment: empirical evidence from Asia-Pacific region. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 29778–29792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala-i-Martin, X. The disturbing `rise’ of global inequality, Working Paper 8904, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2002.

- Kharas, H.; Kohli, H. What is the Middle Income Trap, Why do Countries Fall into It, and How Can It Be Avoided? Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 2011, 3(3), 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P. India in the Rise of Britain and Europe: A Contribution to the Convergence and Great Divergence Debates. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics 2021, 33(1), 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World is Not Enough. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/10569/number-of-earths-needed-if-the-worlds-population-lived-like-following-countries/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Morgan, R.K. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2012, 30(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobac, J.; Alivojvodic, F.; Maksic, P.; Stamenovic, M. Green Face of Packaging - Sustainability Issues of the Cosmetic Industry Packaging. In MATEC Web of Conferences 318; 2020; p. 01022. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, L.W. Lessons for impact monitoring. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(2), 6–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevas, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2012, 30(1), 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Reflections on Social Impact Assessment in the 21 st century. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2020, 38(2), 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, H.H.; Anthony, R.W.; Filderman, L.D. Public concerns method: a means for assessing alternative policies. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(3), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, E. Cumulative Impact Analysis. Impact Assessment 2020, 1(4), 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaram, T.; Das, A. Screening for EIA in India: Enhancing effectiveness through ecological carrying capacity approach. Journal of Environmental Management 2011, 92, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, J. Screening for environmental impact assessment projects in England: what screening? Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2006, 29(2), 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, D.; Biasiolli, A.; Morrison-Saunders, A. Land take and the effectiveness of project screening in Environmental Impact Assessment: Findings from an empirical study. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2017, 67, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenney, A.; Kvaerner, J.; Gjerstad, K.I. Uncertainty in environmental impact assessment predictions: the need for better communication with more transparency. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 2006, 24(1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keken, Z.; Hanusova, T.; Kulendik, J.; Wimmerova, L.; Zitkova, J.; Zdrazil, V. Environmental impact assessment – The range of activities covered and the potential of linking to post-project auditing. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2022, 93, 106726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halla, P.; Merino-Saum, A.; Binder, C.R. How to link sustainability assessments with local governance? – Connecting indicators to institutions and controversies. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2022, 93, 106741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, V.A.; Hack, J. Revealing and assessing the costs and benefits of nature-based solutions within a real-world laboratory in Costa Rica. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2022, 93, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P. The bad, the abnormal and the inadequate. A new institutionalist perspective for exploring environmental assessment’s evolutionary direction. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2022, 95, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Renton, S. Redesigning EIA to fit the future: SEA and the policy process. Impact Assessment 1997, 15(4), 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bina, O. Strategic Environmental Assessment. In Innovation in Environmental Policy? Integrating environment for sustainability; Jordan, A., Lenschow, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2008; pp. 134–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, A.; Therivel, R. Raising the game in environmental assessment: Insights from tiering practice. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2022, 92, 106695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.P. Social Impact Analysis. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(1), 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterbusch, K. Psychological impact theory and social impacts. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(4), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.R. Increasing the utility and utilization of assessment studies. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(2), 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds Jr., R. R.; Wilkinson, K.P.; Thompson, J.G.; Ostresh, L.M. Problems in the social impact assessment literature base for western energy development communities. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(4), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.B.; Flynn, J.H. The group ecology method: a new conceptual design for social impact assessment. Impact Assessment 1982, 1(4), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkey repeals plastic import ban. Available online: https://waste-management-world.com/artikel/turkey-repeals-plastic-import-ban/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Exxon Mobil CEO: No fracking near my backyard. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2014/02/22/exxon-mobil-tillerson-ceo-fracking/5726603/ (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Five ways that ESG creates value. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Strategy%20and%20Corporate%20Finance/Our%20Insights/Five%20ways%20that%20ESG%20creates%20value/Five-ways-that-ESG-creates-value.ashx (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Karwowsky, M.; Raulinajtys-Grzybek, M. The application of corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions for mitigation of environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and reputational risk in integrated reports. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2021, 28, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S. Development of international corporate social responsibility framework and typology. Social Responsibility Journal 2020, 16(5), 719–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Elbanna, S. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework. Journal of Business Ethics 2023, 183, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Lyon, T.P. Greenwash vs. Brownwash: Exaggeration and Undue Modesty in Corporate Sustainability Disclosure. Organization Science 2015, 26, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Sahay, A.; Arora, A.P.; Chaturvedi, A. A toolkit for designing firm level strategic corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Social Responsibility Journal 2008, 4(3), 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.P.; Barbieri, J.C. Innovation and Sustainability in the Supply Chain of a Cosmetics Company: a Case Study. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation 2012, 7, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal 2005, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann-Pauly, D.; Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. Organizational Implications of Managing Corporate Legitimacy in Complex Environments – A Longitudinal Case Study of Puma Working Paper No. 321, University of Zurich, 2012.

- Soytas, M.A.; Atik, A. Does being international make companies more sustainable? Evidence based on corporate sustainability indices. Central Bank Review 2018, 18, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, P.; Roth, L. Director Expertise and Corporate Sustainability. Review of Finance 2023, rfad012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morea, D.; Fortunati, S.; Martiniello, L. Circular economy and corporate social responsibility: Towards an integrated strategic approach in the multinational cosmetics industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 315, 128232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrae, A.S.G. From an Environmental Viewpoint Large ICT Networks Infrastructure Equipment must not be Reused. WSEAS Transactions on Environment and Development 2023, 19, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, C.; Civit, B.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Druckman, A.; Caldeira-Pires, A.; Widema, B. et al. Using life cycle assessment to achieve a circular economy. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 2021, 26, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, X. Environmental Impacts of Cosmetic Products. In Sustainability: How the Cosmetics Industry is Greening up; Sahota, A., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2014; pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Gonzalez, M.; Witte, F.; Martz, P.; Gilbert, L.; Humbert, S.; Jolliet, O. et al. Operational Life Cycle Impact Assessment weighting factors based on Planetary Boundaries: Applied to cosmetic products. Ecological Indicators 2019, 107, 105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Gonzalez, E.; Giraldi-Diaz, M. R.; De Medina-Salas, L.; Velasquez-De la Cruz, R. Environmental Impacts Associated to Different Stages Spanning from Harvesting to Industrialization of Pineapple though Life Cycle Assessment. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, R.L.; Kulatunga, A.K.; Jinadasa, K.B.S.N. Conceptual model of Life Cycle Assessment based generic computer tool towards Eco-Design in manufacturing sector. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 33, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, R.; Elegir, G.; Del Curto, B. Designing for Sustainable Behavior Practices in Consumers: A Case Study on Compostable Materials for Packaging. In Proceedings of the International Design Society: DESIGN Conference; 2020; pp. 1647–1656. [Google Scholar]

- Landi, G.; Sciarelli, M. Towards a more ethical market: the impact of ESG rating on corporate financial performance. Social Responsibility Journal 2019, 15(1), 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Ruf, B.; Chatterjee, S.; Sunder, A. Fund Characteristics and Performances of Socially Responsible Mutual Funds: Do ESG Ratings Play a Role? Journal of Accounting and Finance 2018, 18(6), 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rathner, S. The Influence of Primary Study Characteristics on the Performance Differential between Socially Responsible and Conventional Investment Funds: A Meta Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 2013, 118, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbritter, G.; Dorfleitner, G. The wages of social responsibility — where are they? A critical review of ESG investing. Review of Financial Economics 2015, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, H.-M. The effect of social screening on bond mutual fund performance. Journal of Banking and Finance 2016, 67, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, A.; Poppe, L.; Posch, P. Are Sustainable Companies More Likely to Default? Evidence from the Dynamics between Credit and ESG Ratings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Se Speigeleer, J.; Schoutens, W. Implied Tail Risk and ESG Ratings. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denuwara, N.; Kim, A.; Newenhisen, P.; Gibson, C.; Schork, D.; Hakovirta, M. Corporate economic performance and sustainability indices: a study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. Springer Nature Business & Economics 2022, 2, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Naumer, H.-J.; Yurtoglu, B. It is not only what you say, but how you say it: ESG, corporate news, and the impact on CDS spreads. Global Finance Journal 2022, 52, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisel, F.; Lucke, F. ESG in credit ratings and the impact on financial markets. Financial Markets, Institutions and Instruments 2019, 28, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubel, B.; Scholz, H. Integrating sustainability risks in asset management: the role of ESG exposures and ESG ratings. Journal of Asset Management 2020, 21, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellner, C.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. Corporate social responsibility and Eurozone corporate bonds: The moderating role of country sustainability. Journal of Banking and Finance 2015, 59, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, F.; Migliavacca, M. The Determinants of ESG Rating in the Financial Industry: The Same Old Story or a Different Tale? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, S. Corporate Social Performance Scores of the Firms in Sustainability Index. Muhasebe Bilim Dunyasi Dergisi 2021, 23(1), 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ece, N. A Comparative Analysis of Socially Responsible Investing for Borsa Istanbul Stock Market. Maliye ve Finans Yazilari 2018, 110, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levent, C.E. Sustainability Indices in the Financial Markets, Performance and Intraday Volatility Analysis: The Case of Turkey. Journal of Business Research - Turk 2019, 11, 3190–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Wang, X.; Kreuze, J.G. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance: Comparison analyses across industries and CSR categories. American Journal of Business 2017, 32, 106–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, T.; Casey, K.M. Bank Dividend Policy: Does ESG Rating Matter. Journal of Leadership Accountability and Ethics 2020, 17(6), 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Casey Jr., K. M.; Casey, K.M.; Griffin, K. Does Good Stewardship Reduce Agency Costs in the IT Sector? Evidence from Dividend Policies and ESG Ratings. Global Journal of Accounting and Finance 2020, 4(1), 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brounen, D.; Mercato, G.; Op ’t Veld, H. Pricing ESG Equity Ratings and Underlying Data in Listed Real Estate Securities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempatick, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. Journal of Business Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.M.; Redmond, J.; Simpson, M. A review of interventions to encourage SMEs to make environmental improvements. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2009, 27, 1150–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P. Greening of the Supply Chain: An Empirical Study for SMEs in The Philippine Context. Journal of Asia Business Studies 2007, Spring, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Brint, A.; Shi, E.; Upadhyay, A.; Ruan, X. Integrating sustainable supply chain practices with operational performance: An exploratory study of Chinese SMEs. Production Planning and Control: The Management of Operations 2019, 30, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkey’s Best Practices on Sustainable Development and Green Economy 2012. Available online: https://www.skdturkiye.org/userfiles/file/documents/044ve7kyaettlwt9jjyb0q4e8pcdh5.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2023).

- Baumann-Pauly, D.; Wickert, C.; Spence, L.J.; Scherer, A.G. Organizing Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Large Firms: Size Matters. Journal of Business Ethics 2013, 115, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.K.; Malesios, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Saha, K.; Budhwar, P.; De, D. Adoption of circular economy practices in small and medium-sized enterprises: Evidence from Europe. International Journal of Production Economics 2022, 248, 108496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]