Submitted:

01 August 2023

Posted:

02 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Participatory Democracy, Sustainable Development and Governance in Smart Cities. A Brief Systematic Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Research Design. Objectives, Questions and Hypothesis

2.2. Quantitative Data, Research Methods and Statistical Design

3. Results

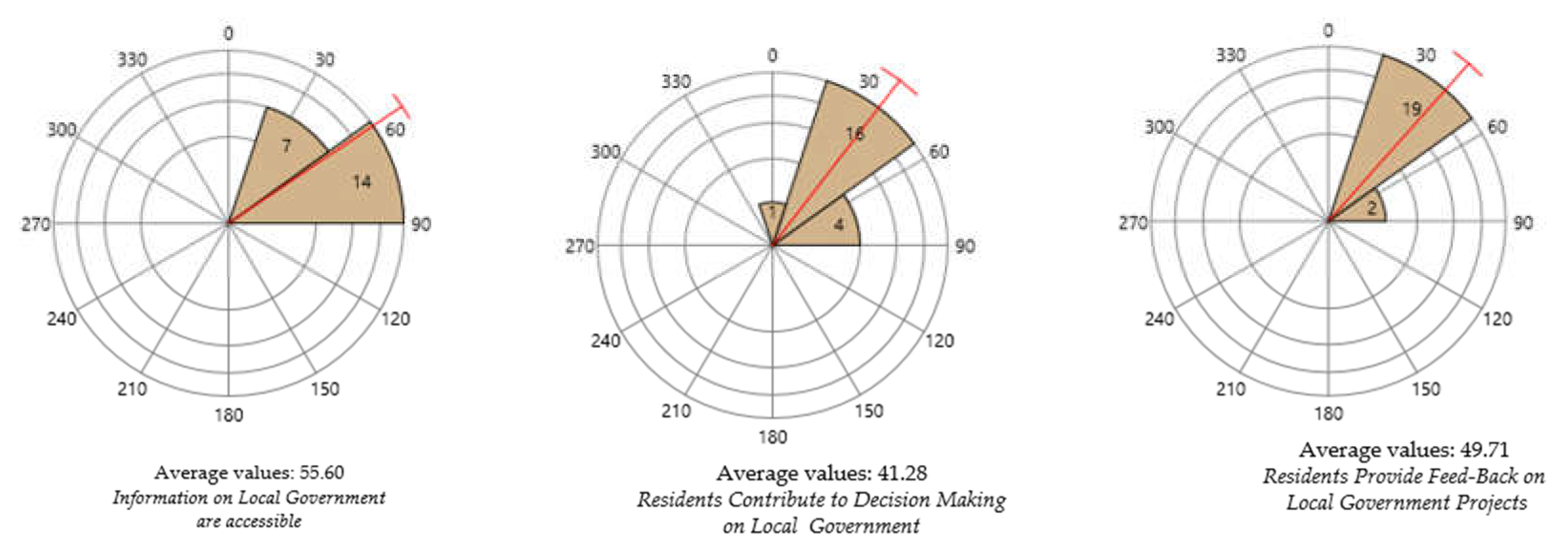

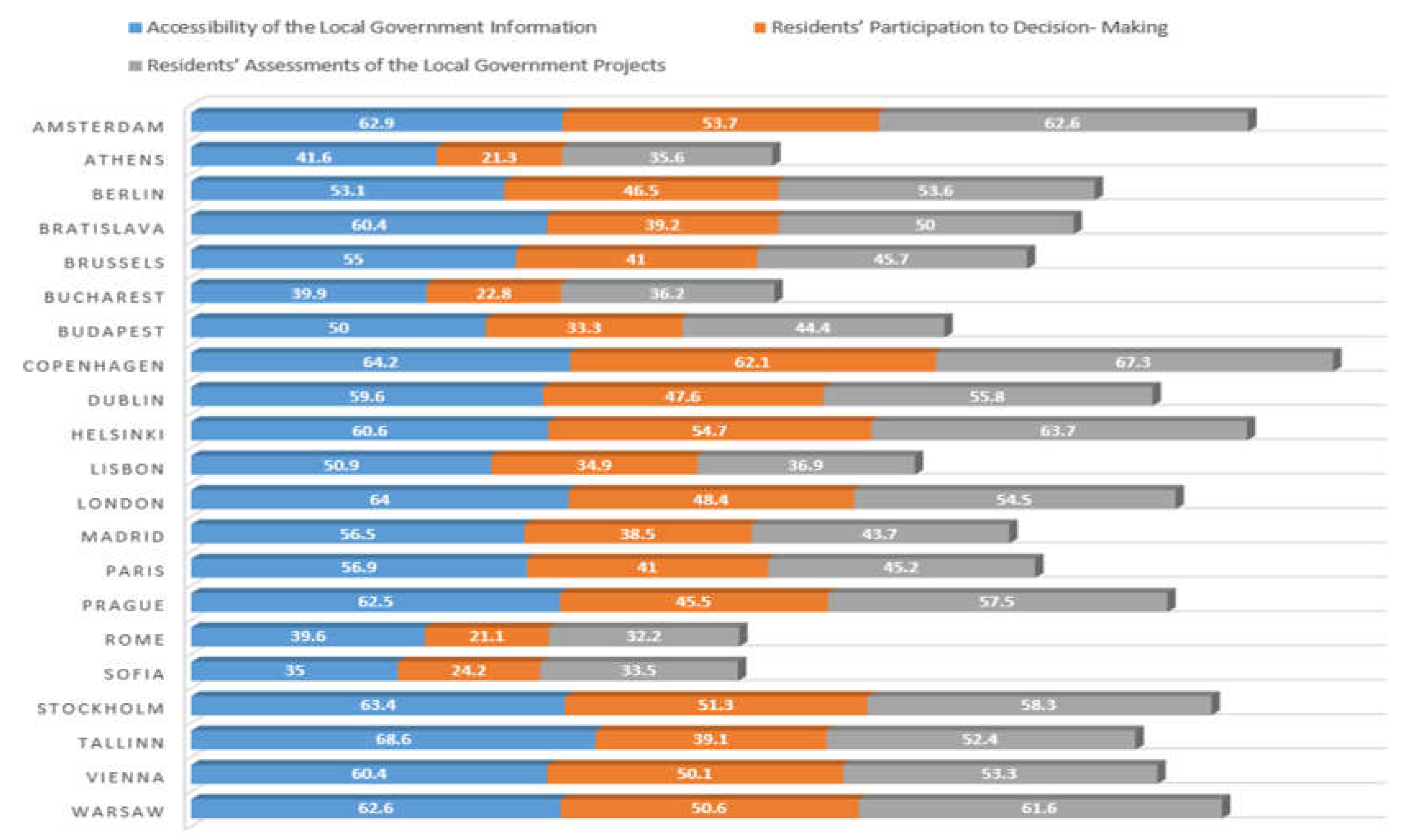

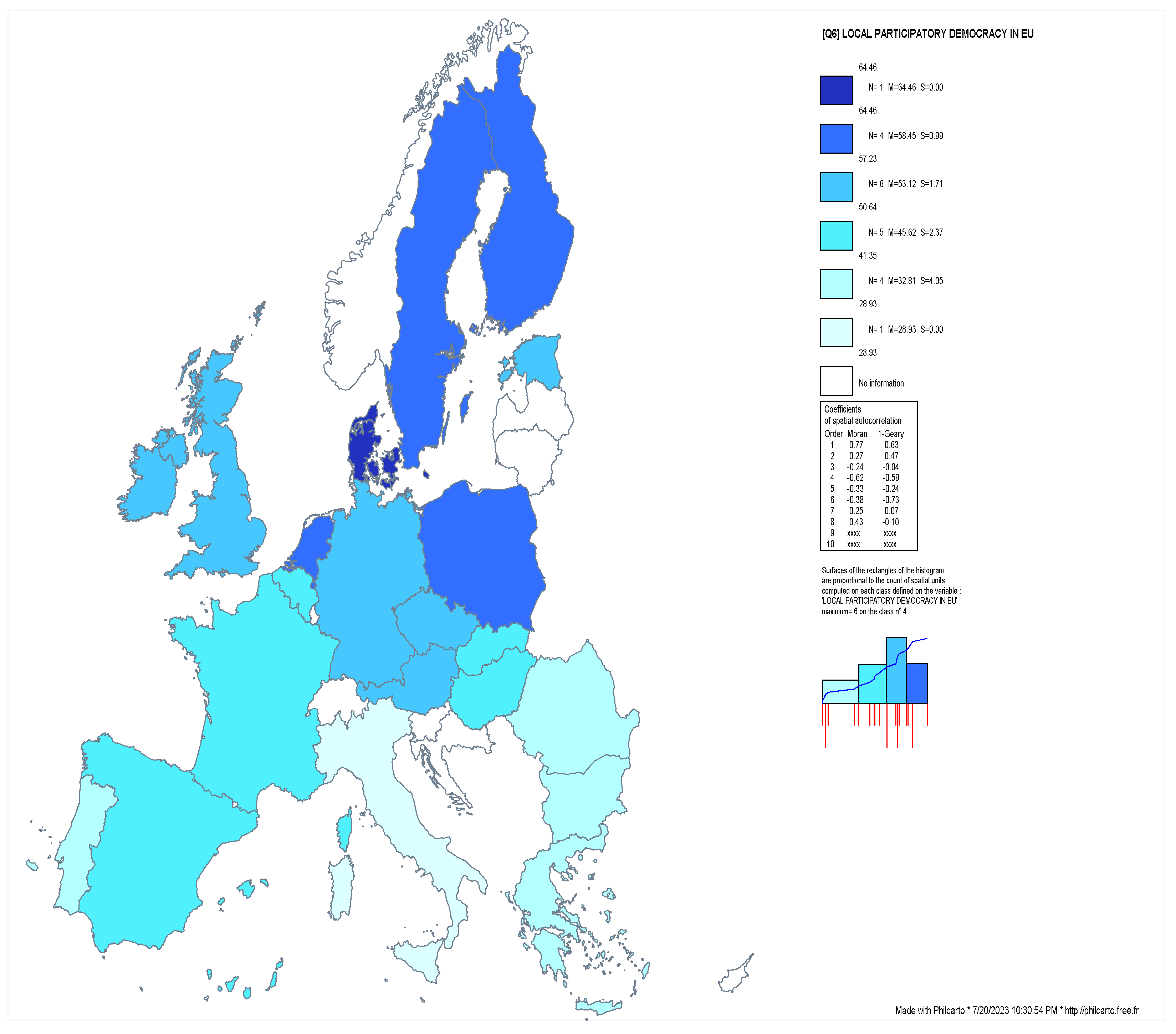

3.1. Mapping Local Participatory Democracy in 21 European Smart Cities

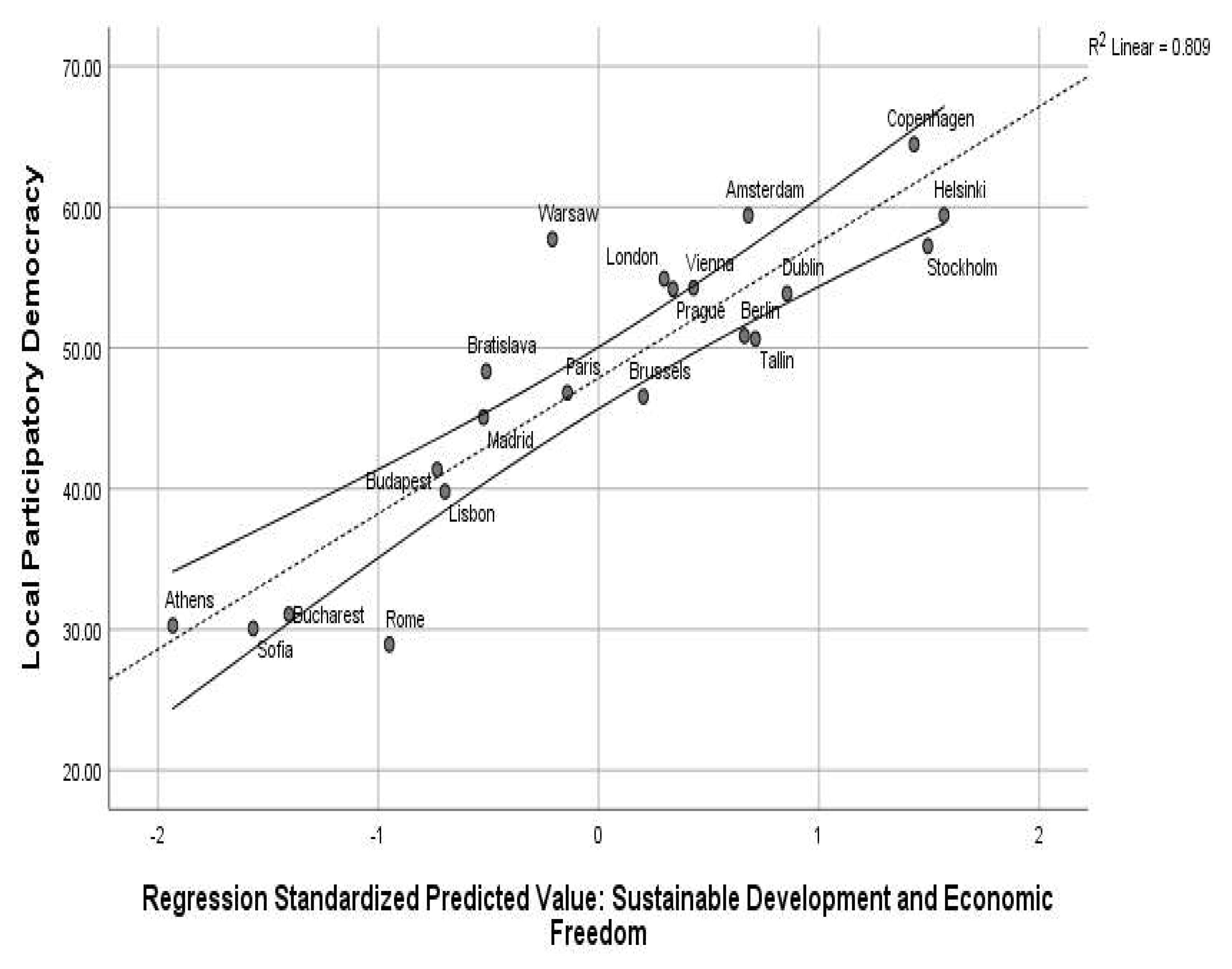

3.2. Predictors of Local Participatory Democracy in 21 European Smart Cities: Economic Freedom and Sustainable Development

| Model | Predictors | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Significance | Collinearity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | T | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF | ||

| 1 | (Constant) | -175.144 | 30.88 | -5.672 | 0.01 | |||

| Sustainable Development Index | 2.782 | 0.385 | 0.856 | 7.228 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| R2= 0.733, p = 0.001 | ||||||||

| 2 | (Constant) | -165.177 | 27.11 | -6.093 | 0.01 | |||

| Sustainable Development Index | 2.073 | 0.427 | 0.638 | 4.853 | 0.01 | 0.614 | 1.629 | |

| Economic Freedom | 0.658 | 0.246 | 0.351 | 2.67 | 0.016 | 0.614 | 1.629 | |

| R2= 0.804, p = 0.016 | ||||||||

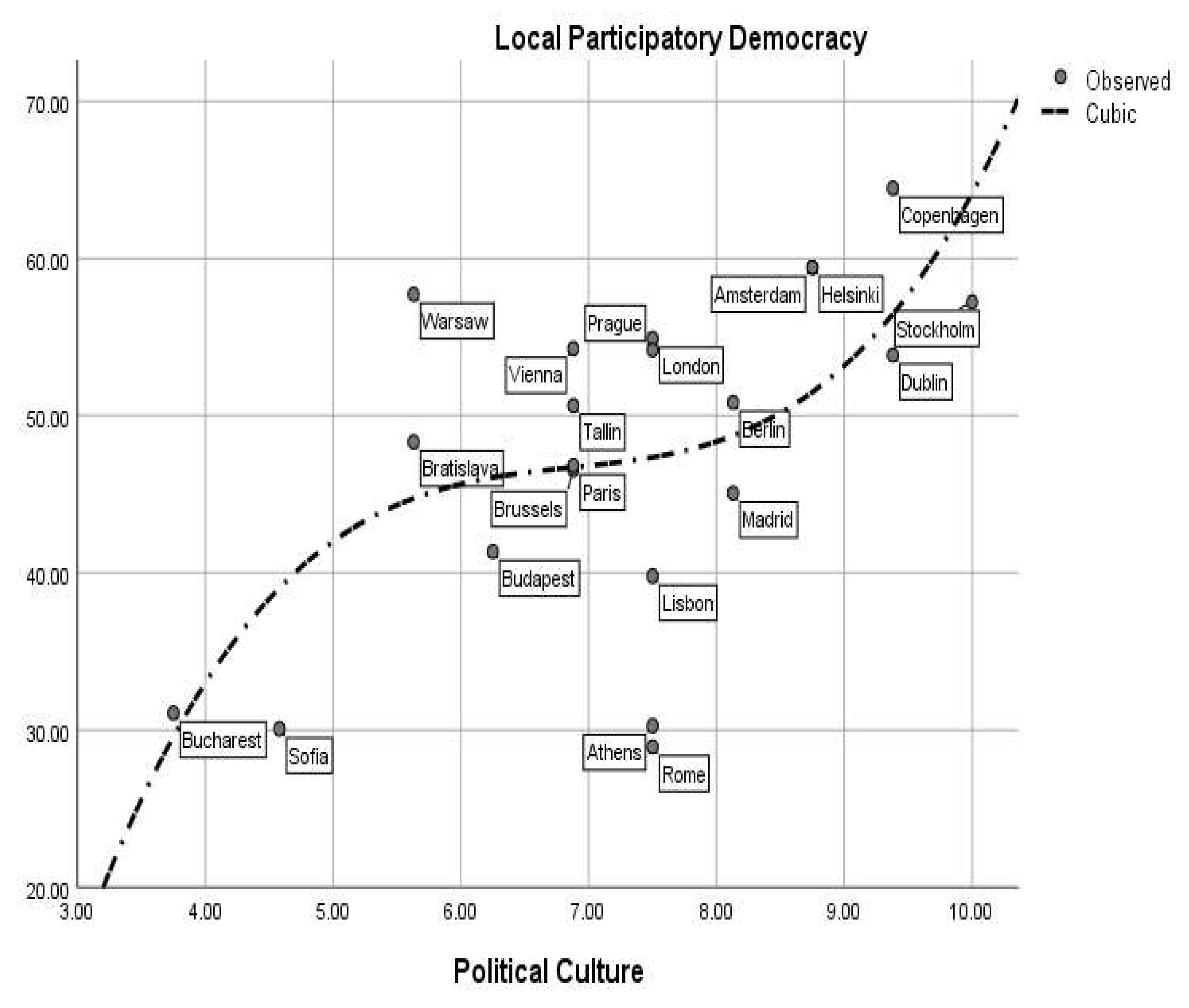

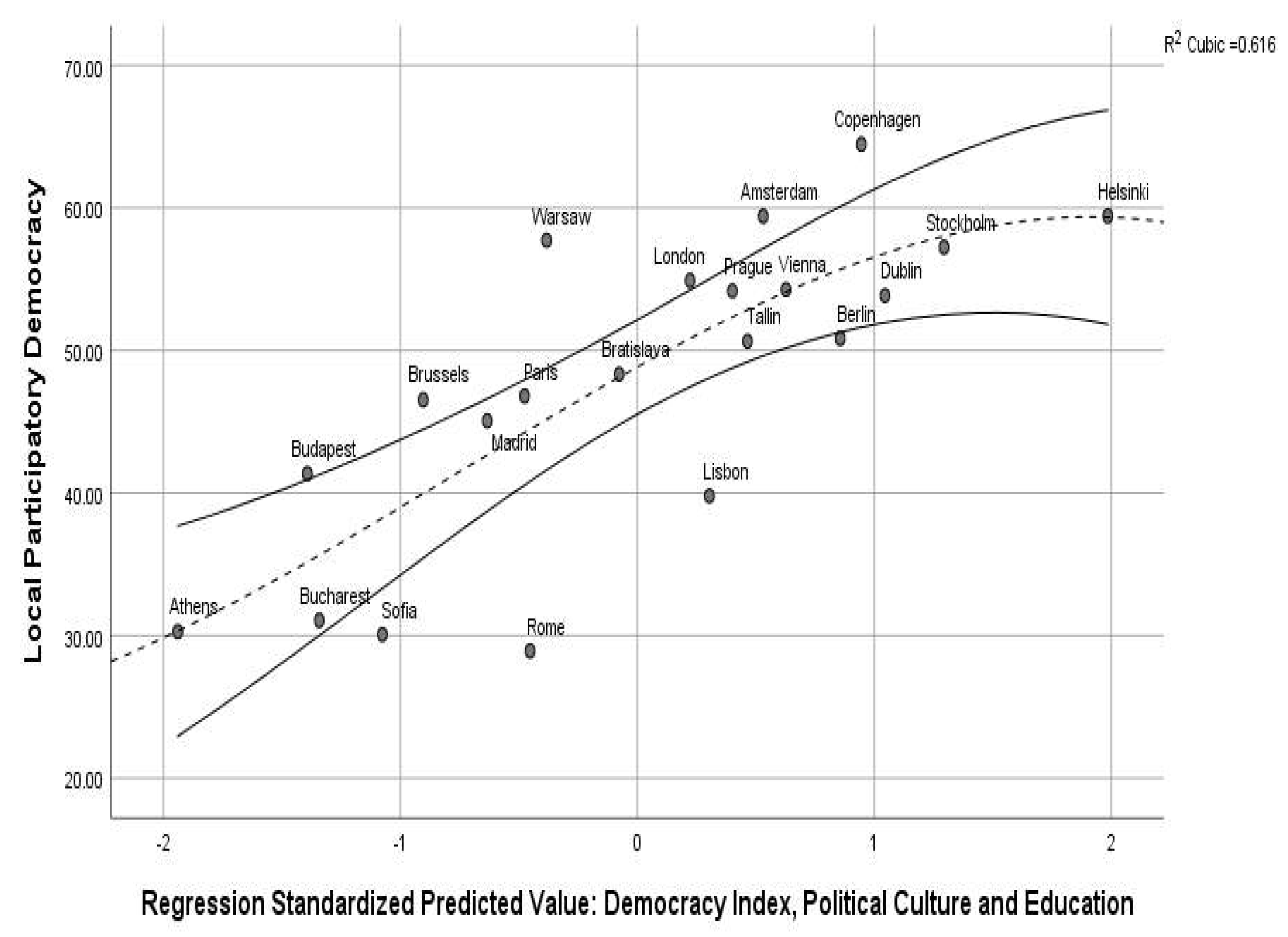

3.3. Non-Linear Associations with LPD in 21 European Smart Cities: National democracy, Political Culture and Education

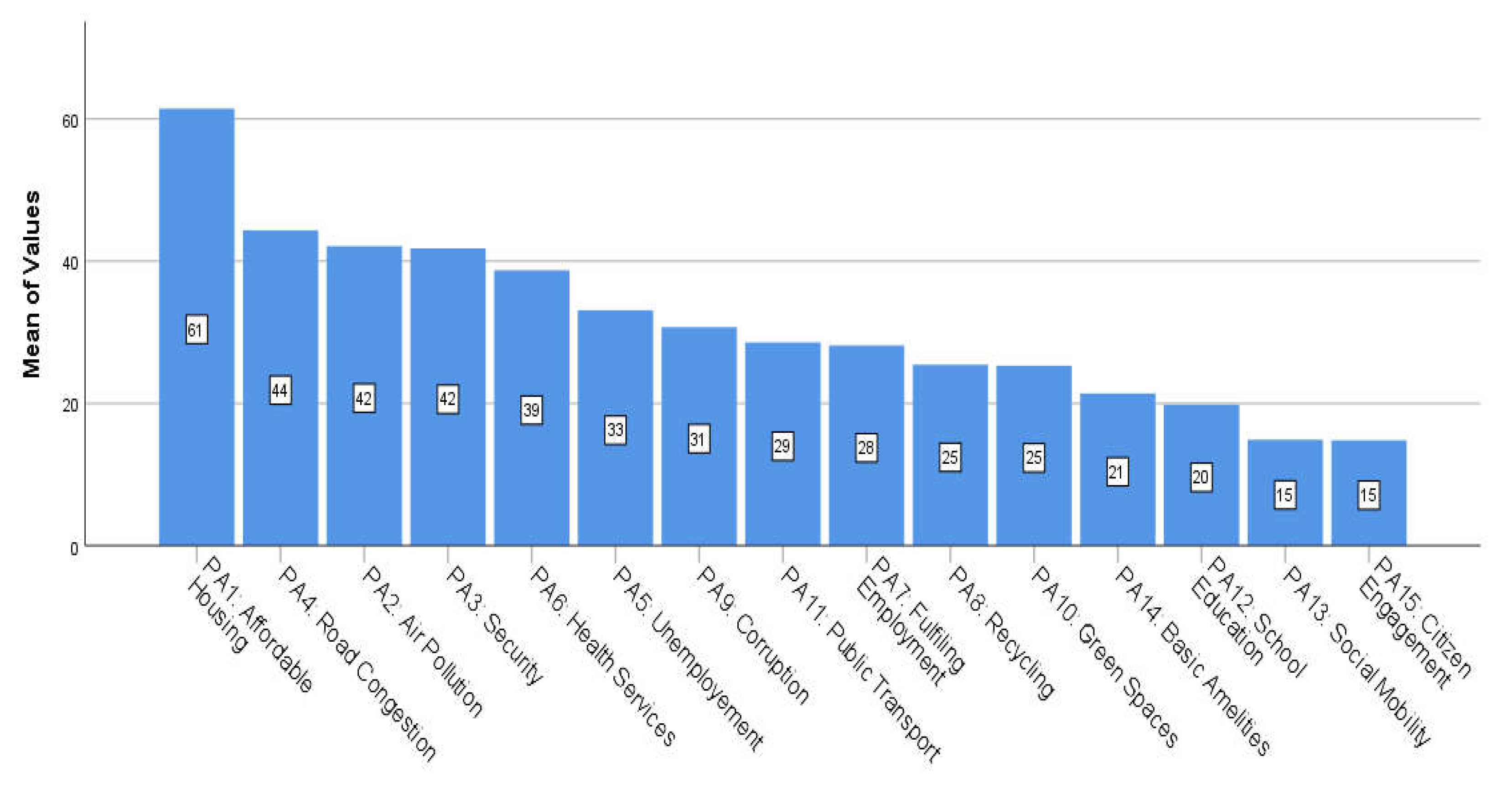

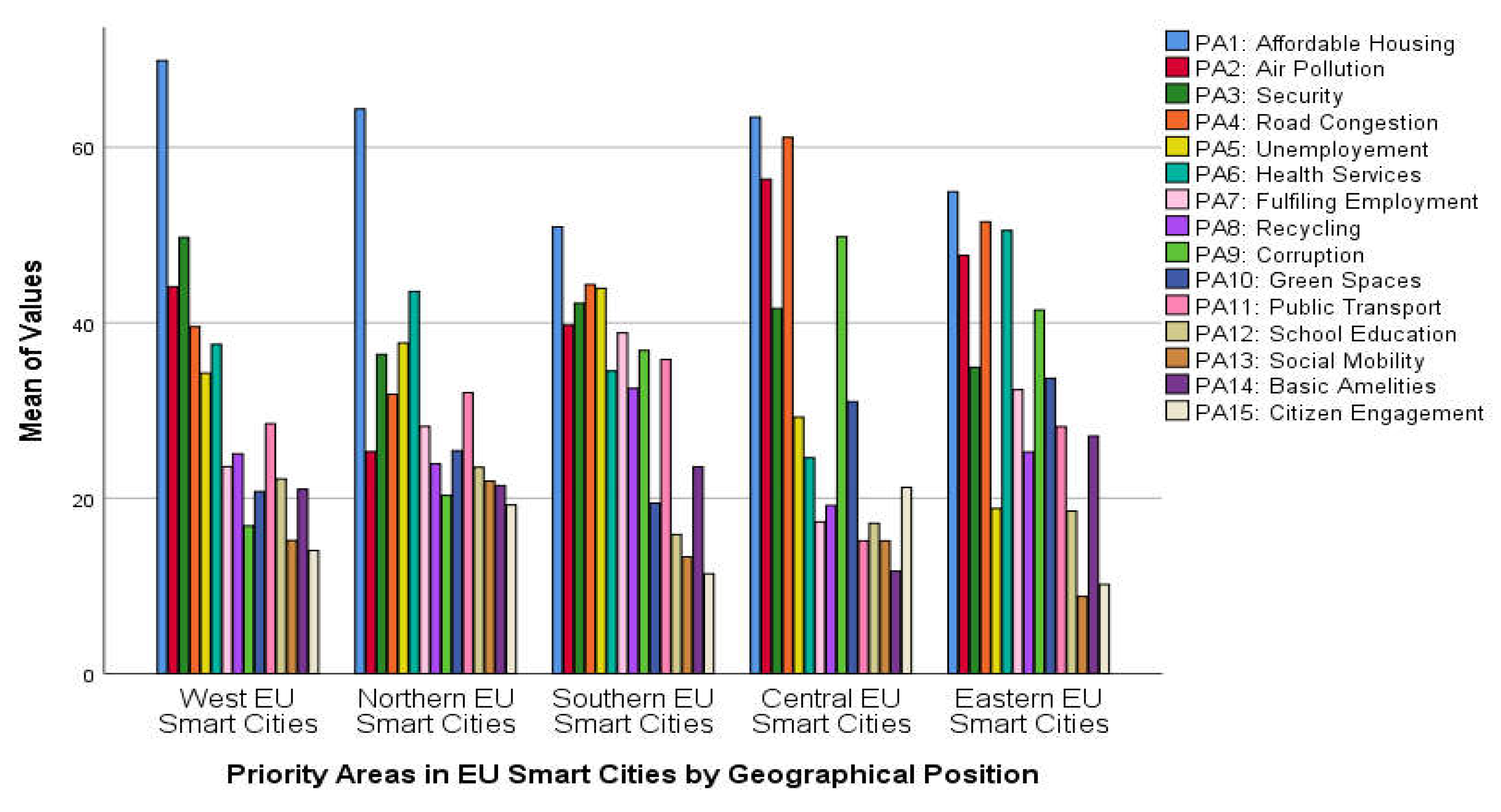

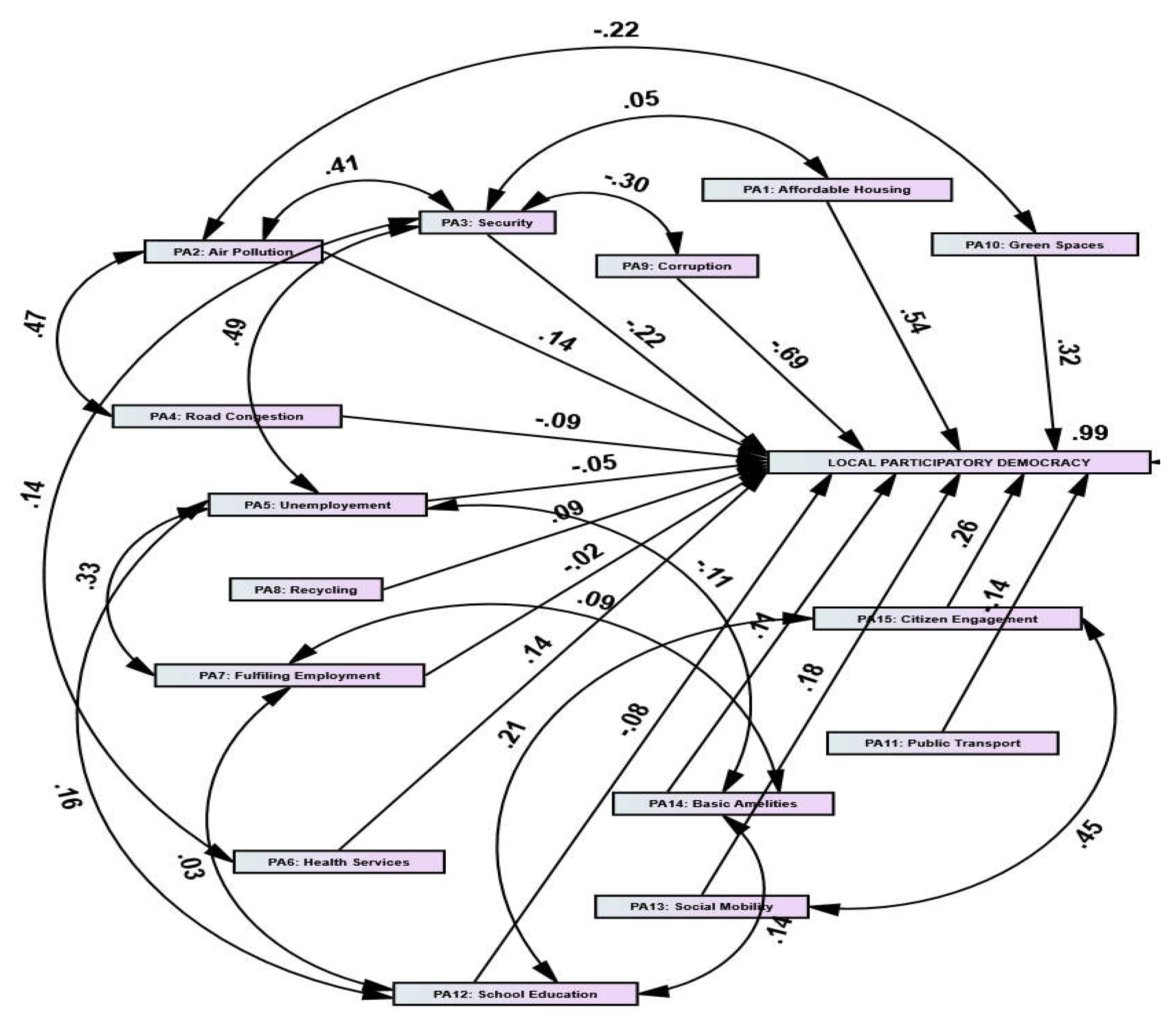

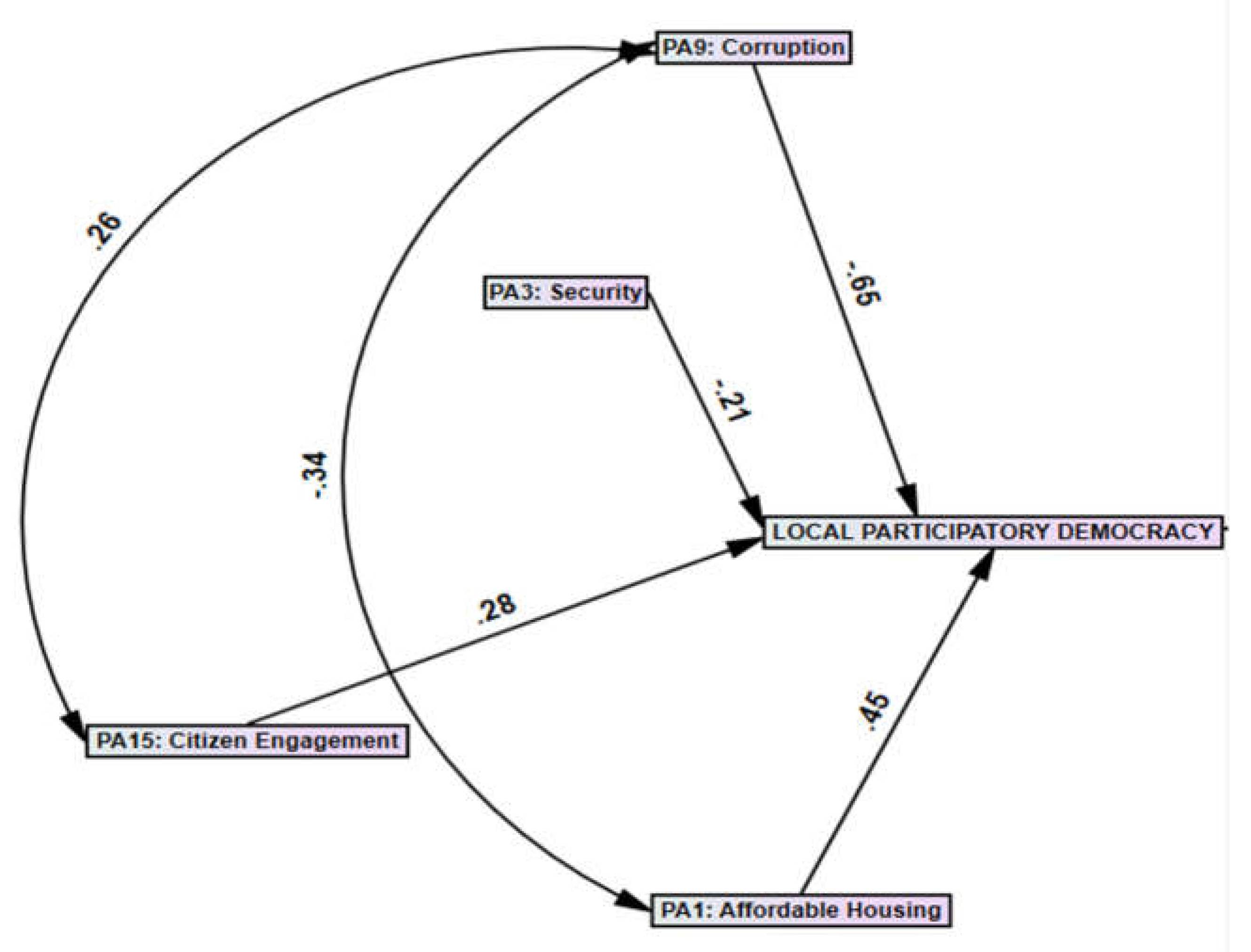

3.4. Priority Areas in 21 European Smart Cities. The SEM Model of Local Participatory Democracy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Batty, M.; Axhausen, K.W.; Giannotti, F.; Pozdnoukhov, A.; Bazzani, A.; Wachowicz, M.; Ouzounis, G.; Portugali, Y. Smart cities of the future. Eur. Phys. J. 2012, 214, 481–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, R.M. Urbanization. 2018. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Yin, C.T.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Cooper, D.; David, B. A literature survey on smart cities. Sci. China Info. Sci. 2015, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakici, T.; Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. A Smart City Initiative: The Case of Barcelona. J. of the Know. Econom. 2012, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Barrionuevo, J.M; Berrone, P.; Ricart, J.E. Smart Cities, Sustainable Progress. IESE Insight. 2012, 14, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives. J.of Urban Tech. 2015, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoun, R.; Zeadally, S. Smart Cities: Concepts, Architectures, Research Opportunities. Com. of the ACM 2016, 59, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S. P.; Choppali, U.; Kougianos, E. Everything you wanted to know about smart cities: The internet of things is the backbone. IEEE Cons. Elect. Mag. 2016, 5, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvaa, B.N; Khanb, M.; Hana, K. Towards sustainable smart cities: A review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sust. Cities and Soc. 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlara, T.; Kamruzzamanf, Md.; Buysb, L.; Ioppoloc, G.; Sabatini-Marquesd, J.; da Costad, E.M.; Yun, J.J. Understanding smart cities: Intertwining development drivers with desired outcomes in a multidimensional framework. Cities 2018, 81, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nuaimi, E.; Al Neyadi, H.; Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J. Applications of big data to smart cities. J. of Int. Serv. and Appl. 2015, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Letaifa, S. How to strategize smart cities: Revealing the SMART model. J. of Busin. Res. 2015, 68, 141–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaroiu, G.C.; Roscia, M. Definition methodology for the smart cities model. Energy 2012, 47, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. Smart cities: A conjuncture of four forces. Cities 2015, 47, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilovaa, E.; Hughesb, L.; Dwivedic, Y.K.; Ramand, K.R. Smart cities: Advances in research—An information systems perspective. Int. J. of Info. Mang. 2019, 47, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujataa, J.; Sakshamb, S.; Tanvic, G. Developing Smart Cities: An Integrated Framework. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2016, 93, 902–909. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Conceptualizing Smart City with Dimensions of Technology People, and Institutions. IN The Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, College Park, USA, 15 June 2011.

- Lai, C.S.; Jia, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, D.; Tao, Y.; Lai, Q.H.; Wong, R.T.K.; Zobaa, A.F.; Wu, R.; Lai, L.L. A Review of Technical Standards for Smart Cities. Clean Technol. 2020, 2, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for Planning the Development of Smart Cities. J. of Urban Tech. 2015, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, R.; Ruhland, S. The governance of smart cities: A systematic literature review. Cities. 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Rodriguez Bolivar, M. P. Governing the smart city: a review of the literature on smart urban governance. Int. Rev. of Adm. Stud. 2015, 0, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereiraa, G.V.; Paryceka, P.; Falcoc, E.; Kleinhans, R. Smart governance in the context of smart cities: A literature review. Inf. Polity. 2018, 23, 23,143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. Making sense of smart cities: addressing present shortcomings. Camb. J. of Region., Econ. and Soc. 2014, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P. Smart Cities: Big Cities, Complex Governance. In Transforming City Governments for Successful Smart Cities; Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.V.; Cunha, M.A.; Lampoltshammer, T.J.; Parycek, P.; Testa, M.G. Increasing collaboration and participation in smart city governance: a cross-case analysis of smart city initiatives. Inf. Techn. for Dev. 2017, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod Kumar, T.M. E-Governance for Smart Cities. In E-Governance for Smart Cities, Vinod Kumar, T.M. Ed.; Springer Science+Business Media: Singapore, 2015; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Paskaleva, K.A. Enabling the smart city: the progress of city e-governance in Europe. Int. J. Innov. and Reg. Dev. 2009, 1, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin, M. Smart cities: the state-of-the-art and governance challenge. Triple Helix 2014, 1, 1–16. Available online: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40604-014-0007-9. [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P.; Benevolo, C. Governing Smart Cities: An Empirical Analysis. Soc. Sci. Comp. Rev. 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Culasso, F. Smart city governance: exploring the institutional work of multiple actors towards collaboration. IJPSM. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, V.; Misuraca, G.; Savoldell, A. Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making. Soc. Sci. Comp. Rev. 2015, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Hu, Q.; Seo, S. -H.; Kang K.; Lee, J. J. Public Participation Consortium Blockchain for Smart City Governance. IEEE Int. of Things J. 2022, 9: 3, 2094-2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Gerli, P.; Ardito, L.; Petruzzelli, A.M. Smart city governance from an innovation management perspective: Theoretical framing, review of current practices, and future research agenda. Techn. 2023, 123, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhlandt, R.W.S. The governance of smart cities: A systematic literature review. Cities, 2018, 81, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesti, G. Defining and assessing the transformational nature of smart city governance: Insights from four European cases. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2018, 86, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaghi, M.; Finger, M. Smart governance for smart cities. Proc. IEEE 2018, 206, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasmeier, K.A.; Nebiolo, M. Thinking about smart cities: The travels of a policy idea that promises a great deal, but so far has delivered modest results. Sustainability 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y. Citizen-centered big data analysis-driven governance intelligence framework for smart cities. Telecomm. Policy 2018, 42, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; van der Voort, H. Adaptive governance: Towards a stable, accountable and responsive government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, R.-M.; Drechsler, W. Agile local governments: Experimentation before implementation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.B.; Navío-Marco, J. Governance and economics of smart cities: opportunities and challenges. Telecom. Policy 2018, 42, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohoryles, R.J. Sustainable development, innovation and democracy and democracy. What role for the regions? Innovation 2007, 20, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sénit, C.A. Leaving no one behind? The influence of civil society participation on the Sustainable Development Goals. EPC: Politics and Space 2020, 38, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, S.; Javaid, F. Interlinkage between Democracy and Sustainable Development. Rev. of Econ. and Develop. Studies 2017, 3, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderbaum, P. Democracy and sustainable development: implications for science and economics. Real-world econ. Rev., 2012, 60, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Söderbaum, P. Reconsidering economics in relation to sustainable development and democracy. The J. of Phil. Econ. 2019, 13, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, S.I.; Teorell, J.; Coppedge, M.; Gerring, J. V-Dem: a new way to measure democracy. J. Dem. 2014, 25, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J.; Hickmann, T.; Backstrand, K.; Kalfagianni, A.; Bloomfield, M.; Mert, A.; Ransan-Cooper, H.; Lo, A. Democratising sustainability transformations: Assessing the transformative potential of democratic practices in environmental governance. Earth Syst. Gov. J. 2022, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkelbaan, J. Governance for the Sustainable Development Goals Exploring an Integrative Framework of Theories, Tools, and Competencies; Springer Nature: Singapore Pte Ltd. 2019.

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, P.Y.; Korine, H. Entrepreneurs and Democracy A Political Theory of Corporate Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.; Borges, M.; Marques, J.L.; Castro, E. Smarter Decisions for Smarter Cities: Lessons Learned from Strategic Plans. In New Paths of Entrepreneurship Development The Role of Education, Smart Cities, and Social Factors, Carvalho, L.C., Rego, C., Lucas, M.R., Sánchez-Hernández, I., Backx, A., Noronha, V., Eds. Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019, pp. 7–30.

- Audretsch, D.B.; Moog, P. Democracy and Entrepreneurship. Entrepr. Th. and Pract. 2020, 0, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H.; Boccia, F.; Tohidi, A. The Relationship between Democracy and Economic Growth in the Path of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farè, L.; Audretsch, D.B.; Dejardin, M. Does democracy foster entrepreneurship? Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegera, T.; Meierrieksa, D. Political capitalism: The interaction between income in\equality, economic freedom and democracy. Eur. J. of Pol. Econ. 2016, 45, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Gounder, R.; Su, J.J. The interaction effect of economic freedom and democracy on corruption: A panel cross-country analysis. Econ. Letters 2009, 105, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, J.A.C. Entrepreneurship and the city. Geogr. Compass 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaa, L.-P.; Salamzadehb, A.; Hadizadehc, M.; Heydarid, G.; Shamsoddin, S. Urban entrepreneurship and sustainable businesses in smart cities: Exploring the role of digital technologies. Sust. Techn. and Entpr. 2022, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, D.; Huang, F. Is democracy good for growth? — Development at political transition time matters. Eur. J. of Pol. Econ. 2023, 78, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, M.D. Economic Freedom, Democracy, and the Quality of Life. World Dev. 2007, 1, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony Simonofski, Estefanía Serral Asensio, Yves Wautelet. Citizen participation in the design of smart cities: methods and management framework. In Smart Cities: Issues and Challenges. Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, C.T. Democracy and governance in the smart city. In Smart Cities: Issues and Challenges. Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, S. Do Smart Cities Produce Smart Entrepreneurs? J. of Theor. And Appl. Elect. Com. Res. 2012, 7, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Sharifi, A. Toward a societal smart city: Clarifying the social justice dimension of smart cities. Sust. Cities and Soc. 2023, 95, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, D. Smart cities and the network society: Toward coomon-driven governance. In Smart Cities as Democratic Ecologies, Araya, D., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, United States of America, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B. Participatory Democracy. In The Encyclopedia of Political Thought, First Edition.; Gibbons, T.M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New Jersey, United States of America, 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.; Griggs, S.; Sullivan, H. Situating the local in the neoliberalisation and transformation of urban governance. Urb. Stud. 2014, 15, 3129–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrett, S.; Sepulveda, L. Urban governance and economic development in the diverse city. Eur. Urb. and Reg. Stud. 2012, 19, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bherer, L.; Dufour, P.; Montambeault, F. The participatory democracy turn: an introduction. J. of Civil Soc. 2016, 12, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmer, J.D. The State of Participatory Democratic Theory. New Pol. Sci. 2010, 32, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutay, A. Limits of Participatory Democracy in European Governance. Eur. Law J. 2015, 21, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G.; Felicetti, A.; Terlizzi, A. Participatory governance in megaprojects: the Lyon–Turin high-speed railway among structure, agency, and democratic participation. Policy and Soc. 2023, 42, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Martín, P.P. Going Beyond the Smart City? Implementing Technopolitical Platforms for Urban Democracy in Madrid and Barcelona. In Sustainable Smart City Transitions, Mora, L., Deakin, M., Zhang, X., Batty, M., de Jong, M., Santi, P., Appio, F.P., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2022; pp. 280–299. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, J. Can democracy accelerate sustainability transformations? Policy coherence for participatory co-existence. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2023, 23, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.; Mahajan, S.; Fricker, R.F.; Carina, A.M.; Hausladen, I.; Carissimo, C.; Carpentras, D.; Stockinger, E.; Sanchez-Vaquerizo, J.A.; Yang, J.; Ballandies, M.C.; Korecki, M.; Dubey, R.H; Pournaras, E. Democracy by Design: Perspectives for Digitally Assisted, Participatory Upgrades of Society. J. of Comp. Sci. 2023, 71, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Brusca, I.; Orelli, L.R.; Lorson, P.C.; Haustein, E. Features and drivers of citizen participation: Insights from participatory budgeting in three European cities. Pub. Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabannes, Y. Participatory budgeting: a significant contribution to participatory democracy. Envin.& Urb. 2004, 16, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Patsias, C.; Latendresse, A.; Bherer, L. Participatory Democracy, Decentralization and Local Governance: the Montreal Participatory Budget in the light of ‘Empowered Participatory Governance’. Int. J. of. Urb. And Reg. Res. 2013, 37.6, 2214–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacombe, R.; Parvin, P. Participatory Democracy in an Age of Inequality. Representation 2021, 57, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- della Porta, D. For participatory democracy: some notes. Eur Polit Sci. 2019, 18, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchton, M.; McNulty, S.; Wampler, B. Participatory Budgeting and Community Development: A Global Perspective. Am. Beh. Sci. 2023, 67, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, J.; Motos, C.R. Participatory Institutions and Political Ideologies: How and Why They Matter? Pol. Stud. Rev. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.; O’Rourke, C. The People’s Peace? Peace Agreements, Civil Society, and Participatory Democracy. Int. Pol. Sci. Rev. 2007, 28, 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissel, B.; Michels, A.; Silagadze, N.; Schauman, J.; Grönlund, K. Public Deliberation or Popular Votes? Measuring the Performance of Different Types of Participatory Democracy. Representation 2023, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.S.; Becker, C.; Roikonen, I. Dialectical approach to unpacking knowledge-making for digital urban democracy: A critical case of Helsinki-based e-participatory budgeting. Urb. Stud. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garga, S.; Mittalb, S.K.; Sharma, S. Role of E-Trainings in Building Smart Cities. Proc. Comp. Sci. 2017, 111, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeeva, E.; Davydova, T.; Skripnikova, N.; Kochetova, L. Human resource development in the implementation of the concept of "smart cities". E3S Web of Conf. 2019, 110, 0–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, T. Inclusive civic education and school democracy through participatory budgeting. Ed. Citiz. and Soc. Just. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttila, J.; Jussila, K. Universities and smart cities: the challenges to high quality. T. Qualit. Manag. & Busin. Excell. 2018, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polletta, F. Participatory Democracy in the New Millennium. Contemp. Soc. 2015, 42, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, C.; Wampler, B. Voice, Votes, and Resources: Evaluating the Effect of Participatory Democracy on Well-being. World Dev. 2010, 38, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The IMD World Competitiveness Center, Smart City Index 2021. Available online: https://imd.cld.bz/Smart-City-Index-2021/38/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- World Bank, GDP growth (annual %). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG?view=chart (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- The Heritage Foundation, Economic Freedom. Available online: https://www.heritage.org/index (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index. Available online: https://www.eiu.com/n/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Sustainable Development Report, Sustainable Development Index. Available online: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Eurostat, Upper secondary education in the EU regions. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20221026-1 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Global Green Growth Index, Social Inclusion. Available online: https://gggi-simtool-demo.herokuapp.com/ (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Index. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics. Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, L. Smart Steps To A Battery City. Gov. News 2012, 32, 24–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzior, A.; Pakhnenko, O.; Tiutiunyk, I.; Lyeonov, S. E-Governance in Smart Cities: Global Trends and Key Enablers. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1663–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacson, J.J.; Lidasan, H.S.; Spay Putri Ayuningtyas, V.; Feliscuzo, L.; Malongo, J.H.; Lactuan, N.J.; Bokingkito, P., Jr.; Velasco, L.C. Smart City Assessment in Developing Economies: A Scoping Review. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1744–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Symbol | Unit of Measurement |

Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility of the Local Government Information | AI | [0-100] | Smart Cities Index |

| Residents’ Participation to Decision- Making | RDM | [0-100] | Smart Cities Index |

| Residents’ Assessments of the Local Government Projects | RA | [0-100] | Smart Cities Index |

| GDP/Capita | GDP | $/ capita | World bank |

| Human Development Index | HDI | [0-1] | United Nations Development Programme |

| Sustainable Development Index | SDI | [0-100] | Sustainable Development Report |

| Education | LE | [0-100] | Eurostat |

| Democracy Index | DI | [0-10] | The Economist Intelligence Unit |

| Economic Freedom | EF | [0-100] | Heritage Foundation |

| Social Inclusion | SI | [0-100] | Global Green Growth Institute |

| Political Culture | PC | [0-10] | The Economist Intelligence Unit |

| Priorities Areas in Smart-Cities | PA | [0-100] | Smart Cities Index |

| Local Participatory Democracy | LPD | [0-100] | Authors ‘estimation based on secondary statistical data |

| Smart Cities | EU-27 Country | Geographical position of the country |

|---|---|---|

| Amsterdam | Netherlands | Western Europe |

| Athens | Greece | Southern Europe |

| Berlin | Germany | Western Europe |

| Bratislava | Slovakia | Central Europe |

| Brussels | Belgium | Western Europe |

| Bucharest | Romania | Eastern Europe |

| Budapest | Hungary | Eastern Europe |

| Copenhagen | Denmark | Nordic Europe |

| Dublin | Ireland | Western Europe |

| Helsinki | Finland | Nordic Europe |

| Lisbon | Portugal | Southern Europe |

| London | UK | Western Europe |

| Madrid | Spain | Southern Europe |

| Paris | France | Western Europe |

| Prague | Czech Republic | Central and Eastern Europe |

| Rome | Italy | Southern Europe |

| Sofia | Bulgaria | Eastern Europe |

| Stockholm | Sweden | Nordic Europe |

| Tallinn | Estonia | Nordic Europe/ Baltic states |

| Vienna | Austria | Central Europe |

| Warsaw | Poland | Eastern Europe |

| Western Europe | Northern Europe | Southern Europe | Central Europe | Eastern Europe | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | Std. Dev. |

Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Mean | Std. Dev. |

| Accessibility of the Local Government Information | 58.58 | ±4.35 | 64.2 | ±3.31 | 47.15 | ±7.94 | 52.63 | ±15.31 | 53.23 | ±10.45 |

| Residents’ Participation to Decision- Making | 46.37 | ±4.84 | 51.8 | ±9.59 | 28.95 | ±9.07 | 39.93 | ±13.82 | 36.48 | ±11.6 |

| Residents’ Assessments of the Local Government Projects | 52.9 | ±6.58 | 60.43 | ±6.5 | 37.1 | ±4.83 | 48.1 | ±12.82 | 48.05 | ±10.66 |

| GDP/Capita | 54738.25 | ±18272.27 | 47301.5 | ±8800.74 | 33669.29 | ±5092.32 | 37670.98 | ±14885.7 | 30602 | ±1419.66 |

| Human Development Index | 0.9 | ±0.03 | 0.9 | ±0.04 | 0.88 | ±0.05 | 0.94 | ±0.01 | 0.9 | ±0.03 |

| Sustainable Development Index | 81.35 | ±0.81 | 84.35 | ±2.11 | 77.51 | ±1.78 | 78.62 | ±4.65 | 78.04 | ±2.33 |

| Education | 82.12 | ±2.59 | 86.76 | ±4.71 | 82.59 | ±6.84 | 87.21 | ±6.11 | 87.07 | ±3.54 |

| Democracy Index | 8.45 | ±0.54 | 8.88 | ±0.69 | 7.79 | ±0.32 | 7.66 | ±0.69 | 6.77 | ±0.28 |

| Economic Freedom | 73.71 | ±6.01 | 77.09 | ±1.03 | 64.57 | ±3.92 | 72.17 | ±1.95 | 67.44 | ±1.13 |

| Social Inclusion | 91.08 | ±1.65 | 90.75 | ±3.18 | 88.14 | ±2.77 | 87.29 | ±5.58 | 82.4 | ±2.7 |

| Political Culture | 7.92 | ±1.02 | 8.75 | ±1.35 | 7.66 | ±0.32 | 6.32 | ±1.54 | 5.32 | ±1.08 |

| Local Participatory Democracy | 52.06 | ±5.00 | 57.94 | ±5.73 | 36.02 | ±7.73 | 46.18 | ±13.94 | 44.62 | ±11.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).