1. Introduction

Primary immunodeficiencies or innate inborn errors of immunity (IEI) are a heterogeneous group of diseases that result from defects in the development and/or function of the immune system. They are classified as disorders of adaptive immunity (ie, T cell, B cell, or combined immunodeficiencies) or innate immunity (eg, phagocyte and complement disorders). Although the clinical manifestations are variable, most disorders involve at least increased susceptibility to infection, autoimmunity, and tumors, and about 60% of these patients have decreased antibody levels [

1]. IEI should be suspected in patients with recurrent upper airway infections (otitis or sinusitis), recurrent pneumonia, continuous use of antibiotics, skin abscesses or atopic dermatitis; or a family history of IEI [

2].

Autoimmune diseases are a group of polygenic, immune-mediated genetic diseases and may involve any organ or system. Although the pathophysiology is still unclear, in all cases, autoantibodies formed against the individual's own tissue begin to destroy it, including the nervous, digestive and respiratory systems, skin, blood, eyes, joints, and endocrine glands [

1,

2]. Autoimmune manifestations are observed with considerable frequency in patients with primary antibody deficiencies, including common variable immunodeficiency and selective IgA deficiency, but can also be evident in patients with combined immunodeficiency disorders (autoimmunity in primary immunodeficiency disorders) [

3]. Autoimmune diseases accounted for about 50.0% of patients diagnosed, supporting the association between autoimmune diseases and IEI, based on the concept that excessive inflammatory responses and autoimmunity are also common manifestations of immunodeficiency [

2].

Cutaneous manifestations are common in patients with IEI and therapies include topical agents, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive or immunobiologic agents [

3]. Over the past 2 decades, several immunobiological agents have been developed for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. The first class included the TNFα inhibitors and the monoclonal antibodies adalimumab and infliximab, followed by the monoclonal antibody ustekinumab, an IL-12/23 inhibitor. A newer class of monoclonal antibodies are the IL-17 inhibitors, including secukinumab and ixekizumab, which block IL-17A, as well as brodalumab, which blocks the IL-17 receptor (IL-17RA). Finally, the IL-23 inhibitors guselkumab, tildraquizumab and risankizumab were added [

4]. The role of ustekinumab in triggering infections in immunocompetent patients has been investigated, however, data on patients with IEI with combined immunodeficiency are scarce because these patients could not be included in clinical studies. Our objective was to investigate the impact of treatment with ustekinumab in triggering infections in a patient with severe uncontrolled psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, and primary late-onset combined immunodeficiency (LOCID) over an 8-year period.

2. Case Report

In 2016, a 32-year-old man was referred to the dermatology and immunodeficiency outpatient clinic at Presidente Prudente Regional Hospital (RH), São Paulo state, Brazil. Skin disorders were present soon after birth in our patient. At 3 months of age, he had atopic dermatitis and he was 1 year old when he was first hospitalized due to a severe infection in the lower limb after an insect bite. Subsequently, throughout his childhood, he was hospitalized about five times a year due to mild and severe skin infections, including cellulitis and erysipelas, in addition to ulcerative atopic dermatitis, making it clear that skin lesions would be a major health problem in his life.

In 2006, at the age of 16 years, he was diagnosed with LOCID and severe psoriasis and referred from Presidente Prudente to the primary immunodeficiency clinic at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo, São Paulo (HC). Due to hypogammaglobulinemia, immunoglobulin deficiency, and alterations in immuno phenotyping with low levels of CD3/CD4 and CD19 cells (

Table 1), he was given intravenous human immunoglobulin (IVIG) replacement at a dose of 400 mg/kg at 28-day intervals, and showed significant improvement. In 2011, IVIG replacement was discontinued due to severe anaphylaxis and he underwent follow-up at HC. From 2011 to 2016, without immunoglobulin replacement, his health condition, psoriasis, and infections were exacerbated.

In May 2016, at the first consultation in RH, and after 5 years without follow-up in a specialized immunodeficiency service and without replacement IVIG, his state of health was poor, with multiple infections and comorbidities, mainly in the skin, and worsening of his psoriasis, leading to difficulty carrying out basic daily activities. In November 2016, subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement was started, a new form of therapy that protects the patient from an anaphylactic reaction and adverse events. He had widespread pruritic erythematous scaly plaques, including the palmoplantar regions (

Figure 1), which were not controlled after using topical corticosteroids, systemic acitretin, and UVB-narrow band phototherapy. The Psoriasis Area Severity Index was >10. Tests, including serology for hepatitis B and C, HIV and syphilis, PPD (purified protein derivative), and chest radiographs were requested before starting immunobiological therapy. Given the importance of his immunodeficiency, it was decided not to give methotrexate or anti-TNF-α agents because of their immunosuppressive effect and a greater risk of reactivating latent, occult, or recurrent infections. Ustekinumab was indicated. Before starting treatment in this immunosuppressed patient, prophylaxis with isoniazid for

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for pneumocystosis, fluconazole for candidiasis, and azithromycin for atypical mycobacteria was given. About 30 days after the use of the prophylactic drugs, he had important side effects, including diarrhea, epigastric pain, dehydration, and a decline in his general condition requiring hospitalization, and prophylactic treatment was interrupted. On 17 Fewbruary 2017, the standard initial dose of ustekinumab (45 mg at weeks 0 and 4) was administered subcutaneously followed by a maintenance dose of 45 mg every 3 months, the standard label dosage for psoriasis with or without arthritis for adults weighing <100 kg.

He showed significant improvement after 2 doses of medication (

Figure 2) and remained on this dosage until the end of 2019. In 2020, due to the worsening of his joint condition, and the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, the dose of ustekinumab was adjusted, first doubled (90 mg every 3 months), but the joint pain did not improve; then, the interval between doses was decreased (90 mg every 8 weeks).

In May 2022, the patient presented with worsening of abdominal pain and diarrhea, leading to dehydration and weight loss. Colonoscopy with biopsies revealed Crohn disease and upper digestive endoscopy with duodenal biopsy demonstrated villous atrophy and infiltration of intraepithelial lymphocytes, compatible with celiac disease; there was clinical improvement of diarrhea after suspension of gluten intake.

In April 2023, he was hospitalized due to severe dehydration caused by diarrhea and vomiting, in addition to fever, probably due to significant worsening of Crohn disease, having received intravenous antibiotic therapy. The 90-mg intravenous loading dose was given for Crohn disease with an 8-week interval between doses; this led to improvement in Crohn disease and psoriasis. From 2017 to 2022, he was infected with COVID-19, dengue (twice), and influenza virus, and was hospitalized three times for intravenous antibiotic therapy.

At present, he continues with the optimized treatment with ustekinumab; replacement of subcutaneous immunoglobulin every 28 days, and is followed up at immunology, dermatology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology clinics.

With regard to family history, the sister is being followed up due to juvenile idiopathic arthritis and vitiligo; his brother has rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, diarrhea, anal fistula, bilateral deafness after using monoclonal antibodies to treat the anal fistula; a cousin was diagnosed with common variable immunodeficiency, thrombocytopenia, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (died aged 28 years); an aunt was diagnosed with combined immunodeficiency, thrombocytopenia and autoimmune hemolytic anemia (died aged 54 years); a nephew died soon after birth due to probable severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome.

In 2016, ustekinumab was approved in Brazil for the treatment of psoriasis in the case of failure or contraindication of a classic systemic treatment (in his case, phototherapy and acitretin).

2.1. Genetic diagnosis

Genetic sequencing for primary immunodeficiencies was performed through exon capture (peripheral blood) with Nextera Rapid Capture Mendelics Custom Panel V2, followed by next-generation sequencing with Illumina HiSeq (alignment and identification of variants using bioinformatics protocols, with reference to the GRCh37 version of the human genome) (Mendelicx, São Paulo, Brazil). The following genes were analyzed: ADA AICDA BLNK BTK CASP10 CASP8 CD19 CD247 CD3D CD3E CD3G CD40 CD40LG CD79A CD79B CD8A CIITA CYBA CYBB DCLRE1C ELANE FAS FASLG FOXN1 FOXP3 G6PC3 GATA2 GFI1 HAX1 IFNGR1 IFNGR2 IGLL1 IL12RB1 IL. Pathogenic variants of 2RG IL7R JAK3 LIG4 LRRC8A LYST MAGT1 MPO MYD88 NCF1 NCF2 NCF4 NFKBIA NHEJ1 NRAS ORAI1 PIK3CD PNP PRF1 PTPRC RAB27A RAC2 RAG1 RAG2 RFX5 RFXANK RFXAP SERPING1 SH2D1A STAT1 STAT5B STX11 STXBP2 TAP1 TAP2 TAPBP UNC13D UNG WAS WIPF1 XIAP were not found.

Whole exome sequencing was performed by 3B-Exome Report and no clinically significant variant was detected (3 Billion, South Korea).

3. Discussion

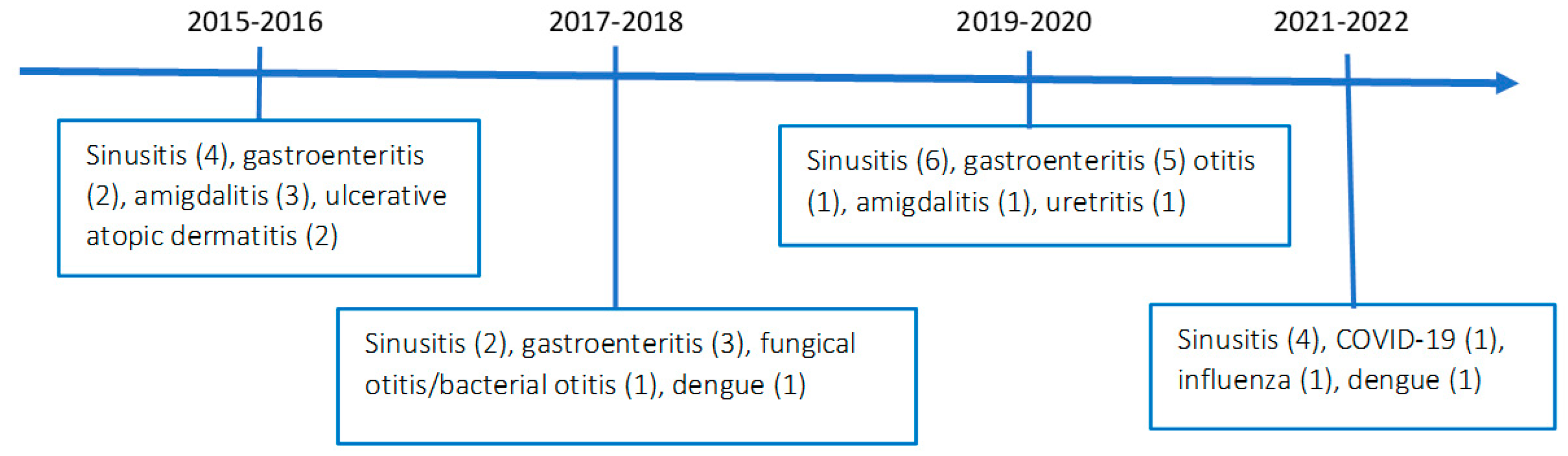

A case report is presented for a patient with combined immunodeficiency with severe plaque psoriasis, Crohn disease, and psoriatic arthritis with 8-year follow-up treated with ustekinumab. Chronic sinusitis, gastroenteritis, fungal and bacterial otitis, and community-acquired pneumonia were the main infections, and he was hospitalized three times for intravenous antibiotic therapy (

Figure 3).

Skin disorders were diagnosed early in our patient. At 3 months of age, he presented eczematous dermatological lesions on the upper and lower limbs, trunk and cervical region. His first hospitalization was at the age of one year due to a severe infection in the lower limb followed by an insect bite. In childhood, he had several hospitalizations due to mild and severe skin infections, including cellulitis, erysipelas and ulcerative atopic dermatitis, making it clear that skin lesions would be a major health problem in his life. Autoimmunity and skin disorders are prominent features in patients with IEI, and recognition of specific skin conditions associated with IEI in combination with other clinical features may raise suspicion of an underlying IEI [

5]. However, only at the age of 16 he develop severe plaque psoriasis and was referred from Presidente Prudente, in the countryside, to a reference center for immunodeficiency in São Paulo (HC), with a diagnosis of late-onset combined immunodeficiency. Despite presenting alarming signs of IEI, including persistent severe infections of the upper and lower airways, multiple annual hospitalizations for infectious diseases and autoimmune disorders, IEI was diagnosed late in the patient. The distribution of IEI reference centers in Brazil is poor; IEI network centers are concentrated mainly in big cities and capitals of the southeast region [

1]. In Presidente Prudente, an immunodeficiency reference center was established only in 2014, and on that occasion more than 12 patients diagnosed with IEI were unaccompanied, without monthly immunoglobulin replacement, and mostly in a poor state of health, similar to our patient [

1].

In our patient, treatment with ustekinumab and the possibility of monthly subcutaneous replacement with immunoglobulin was a turning point in his life, with improvements in his skin psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and Crohn disease as well as infectious disease control. Furthermore, the beneficial effect that immunoglobulin replacement has on autoimmune diseases is well documented, decreasing their intensity and modulating their activity [

6,

7]. In 2017, when he started ustekinumab, a broad literature was available on its effects in triggering infectious diseases [

8,

9], however, as far as we know, no literature was available on immunodeficient patients. We were concerned that by using a strong immunosuppressive drug on a patient who was already genetically immunosuppressed, his infections might become more frequent and severe, putting his life at risk. Surprisingly, his history of infections between 2017 and 2022 showed a controlled number of infections, common to patients with CIVD; sinusitis and gastroenteritis were the most prevalent. It is noteworthy that he was hospitalized only three times to receive high-spectrum intravenous antibiotics.

The mechanisms by which ustekinumab triggers infectious diseases are well described. Ustekinumab can inhibit IL-12 and IL-23 signaling, activation, and cytokine production, resulting in downregulation of the immune system, reducing inflammation and the immune response, and increasing the vulnerability to infectious diseases. For ustekinumab, multiple cases of infections have been described in clinical trials and case reports [8-10]. Recently, the World Health Organization Pharmacovigilance Center published the global risk of bacterial skin and Herpesviridae infections with ustekinumab, secukinumab, and TNF-α inhibitors. For bacterial skin infections, ustekinumab showed the strongest association compared with secukinumab and TNF-α inhibitors. Ustekinumab showed a higher relative risk for skin infections among patients with psoriasis [

10]. However, conflicting results were found in a nationwide cohort study from France covering approximately 99% of the French population. In the association between the use of biologics and the risk of serious infection in patients with psoriasis after treatment with biologicals, ustekinumab was associated with a lower risk of having a serious infection compared with adalimumab or infliximab and etanercept [

11].

It is important to emphasize that CVID is a clinical and immunological description of a syndrome characterized by a decrease in the amount and function of antibodies leading to recurrent severe infections often requiring inpatient antibiotic therapy. Sometimes is associated with immunoregulation features, such as organ-specific or systemic immunity, granulomatous manifestations, benign and malignant lymphoproliferative, and also susceptibility to neoplastic diseases of solid organs. In addition, due to the complex nature of CVID, associated today with the discovery of dozens of different genes that lead to its multiple clinical and immunological characteristics, CVID, as well as several IEI therapy are gaining a new life of personalized therapies. They depend on the affected gene, and its effect on several pathways associated with specific mutations that show characteristics of loss or gain of function, so mutations in the same gene may require different therapies. Due to the great communication of biological pathways, different approaches can be used for different patients with a similar clinical picture, raising the possibility of controlling immune dysregulations. They tend to be a significant aggravating factor for patients with CVID, very common in the clinical practice of specialists as well as generalists around the world [

12].

Because patients with primary or secondary immune deficiency cannot be included in clinical trials, few publications on the role of ustekinumab treatment in triggering infectious diseases are available. A patient with Crohn disease and transient IgM and IgG immunodeficiency treated with ustekinumab presented fungal endocarditis, esophageal moniliasis, and septic condition of undetermined origin [

13]. In a cohort of nine patients with chronic granulomatous diseases (CGD), ustekinumab was found to safe with efficacy for the treatment of CGD-associated inflammatory bowel disease [

14]. Corroborating our results, ustekinumab is the most appropriate non-anti-TNF immunobiological for the treatment of psoriasis, Crohn disease, and psoriatic arthritis diseases in our patient. It is not inadvisable to use IL-17 blockers because they worsen or decompensate inflammatory bowel disease, and IL-23 blockers are not approved for its treatment.

Our study is innovative because few reports are available in the scientific literature on the role of ustekinumab in triggering infectious diseases in patients with IEI and there are no reports on patients with combined immunodeficiency. Furthermore, the study has global relevance because the ustekinumab treatment continues to be approved for more indications, increasing the number of patients at risk of infectious diseases. It is important to determine the risk of infectious diseases and be permanently vigilant.