1. Introduction

The search for behavioural indicators in horses that allow the recognition of stable behaviours during the life of horses (temperament, personality) at an early stage in life has been the subject of many studies, comprising the use of various methodologies, with emphasis on behavioural parameters like vigilance, gregariousness, reactivity to humans, sensory sensitivity, and locomotor activity. However, it lacks more studies to fully understand these interrelationships, which becomes essential if behavioural characteristics potentially impact injury risk, the human-horse relationship, management, and breeding practices. Turning out that identifying the better purpose for a horse – whether work, sport, or leisure, as well as their well-being, can be optimised by directing management, training strategies, and the kind of human personality that better suits to relevant temperament aspects of that horse [

1,

2].

Several researchers presented correlations between behaviours presented by foals throughout their development [3-12]. Similarly, correlations between behavioural parameters presented during tests that challenge the courage or emotional stability and gregariousness of horses, such as novel object, isolation, transposition, or surprise tests, among others, have been reported [3,5-8].

Generally, behavioural parameters related to horses' temperament have been assessed using experimental tests and survey approaches [

8]. Most researchers, like [

1,

4] chose objective behavioural tests to evaluate equine temperament for many reasons, including ease of replication of the methodology, to facilitate the comparison of individuals in a standardised way, and the concept that there is greater precision in measurements obtained with objective methods. However, despite these advantages, there are some counterpoints which may justify the use of alternative methods. Ijichi et al. [

9] considers that objective assessment of equine personality is typically time-consuming, contrasting to subjective assessments, which experienced caregivers can collect quickly. Another interesting point is that subjective assessment may also contribute to understanding the horse "as a whole", an essential concept towards achieving welfare3. In other words, by understanding how an individual horse will express stress, it is more likely to be able to promote welfare to him [

9]. It is important to emphasise that to obtain a valid subjective assessment of horse temperament, highly experienced human raters are essential, specifically regarding typical behaviours, familiarity with a range of personalities and familiarity with the focal animal for a considerable period, ideally in multiple contexts [

9]. Manrique et al. [

14] perceive growing awareness about individual behavioural differences, contributing to improved management, production, and horses' welfare.

Although much information regarding horse temperament is available in numerous publications, points still need to be addressed. For instance, [

14] indicate the need for more information on how early temperamental differences between horses emerge and whether they persist across different developmental stages. Seaman, Davidson and Waran [

4] understand that it would greatly benefit many people who deal with horses the feasibility of tests that could assess their temperament and predict their behavioural responses in a simple, quick, and practical way while being interpretable in terms of practical situations. A complementary necessity was considered by [

9] regarding assessing whether behaviours presented during tests could generalise to behaviours observed during similar and dissimilar stimuli in everyday training and handling.

To our knowledge, this is the first time that behaviours presented by foals at routine managements are correlated with behavioural indicators of temperament when the animals are older. It could be helpful to use behaviours shown during standard farm handling as temperament indicators and thus target training strategies and purpose of use (work, sport, leisure), optimising resources and animal welfare. To investigate this possibility, we evaluated the maintenance of behaviours presented by foals during interactions with humans resulting from real farm routine managements at different ages and whether there is a correlation with behaviours shown during new object transposition test when the animals were older.

We expect to find evidence if it is possible to use behaviours presented by foals in routine handling managements as indicators of behaviour when they are older, with the expectation of identifying individual variability in the temperament of foals, allowing direct handling and training systems that promote the human-horse interaction, as well as the horse's performance whether in sport, work or leisure, minimising the risk of accidents and increasing the well-being of horses.

3. Results

Regarding the behavioural parameters registered during the forced human approach and manipulation test during navel treatment, on the first day of live and first human: horse interaction, 50.0% of the foals were not curious toward humans, 45.8% curious and 4.2% very curious. Most foals (56.5%) were relaxed, and 43.5% were vigilant. Seventy-five per cent (75.0%) of the foals presented occasional skin shakings (tickle) when touched by humans during this interaction, 20.80% showed no tickle during the interaction, and 20.8% showed tickle during all the interaction. Almost half of the foals (45.8%) mainly accepted the approach and tried to escape mildly from human interaction, while 25.0% totally accepted approximation, manipulation, and contention, 12.5% didn't accept at some point during the interaction, and 16.7% doesn't accept approximation, human interaction during all the interaction time.

During the first human-horse interaction at haltering management, which occurred at weaning (foals were seven months old on average), 40.0% of the foals showed some curiosity towards humans. In contrast, 36.0% displayed high curiosity towards humans. Most foals (56.0%) were relaxed during the first management, and 44.0% were vigilant. The greater part of the foals (64.0%) showed some tickle during the interaction, 24.0% showed tickle during all the interaction, and 12.0% showed no tickle. One-third of the foals (32.0%) totally accepted approximation, manipulation, and contention during the interaction, 28.0% mostly accepted the approach and tried to escape mildly from human interaction, 28.0% didn't accept approximation or human interaction at some point in the interaction, and 12.0% doesn't accept approximation or human interaction during all the interaction time.

At the novel object transposition test, conducted when the foals were one year old on average, 44.0% moved frequently or were interested in the novel object, 36.0% moved little or did not show much interest in the novel object, 12.0 % moved continuously or entirely focused on the novel object and 8.0% moved very little or were uninterested in the novel object. More than half of the foals (60.0%) moved frequently and relaxed towards the new object and crossed it, 20.0% approached the new object reluctantly and crossed it, 12.0% moved continuously and relaxed towards the new object and crossed it, and 8.0% did not cross the obstacle. Most foals (64.0%) transposed the novel object at walk, 12.0% jumping, 8.0% at trot, 8.0% stepped on the novel object, and 8.0% didn't transpose the novel object.

Behavioural parameters presented during the transposition test, when the foals were one year old on average, were correlated with behaviours shown during the forced human approach and manipulation test, performed during routine handling when they were younger (at birth and seven months).

In general, foals in the transposition test showed more remarkable exploratory behaviour. They were more confident and with better transposition efficiency of the novel object correlated with foals that were more attentive to humans, more relaxed, with less tickling and accepted human approach and manipulation better when younger. How these correlations took place is described below (

Table 2).

3.1. Exploratory behaviour at the arena test

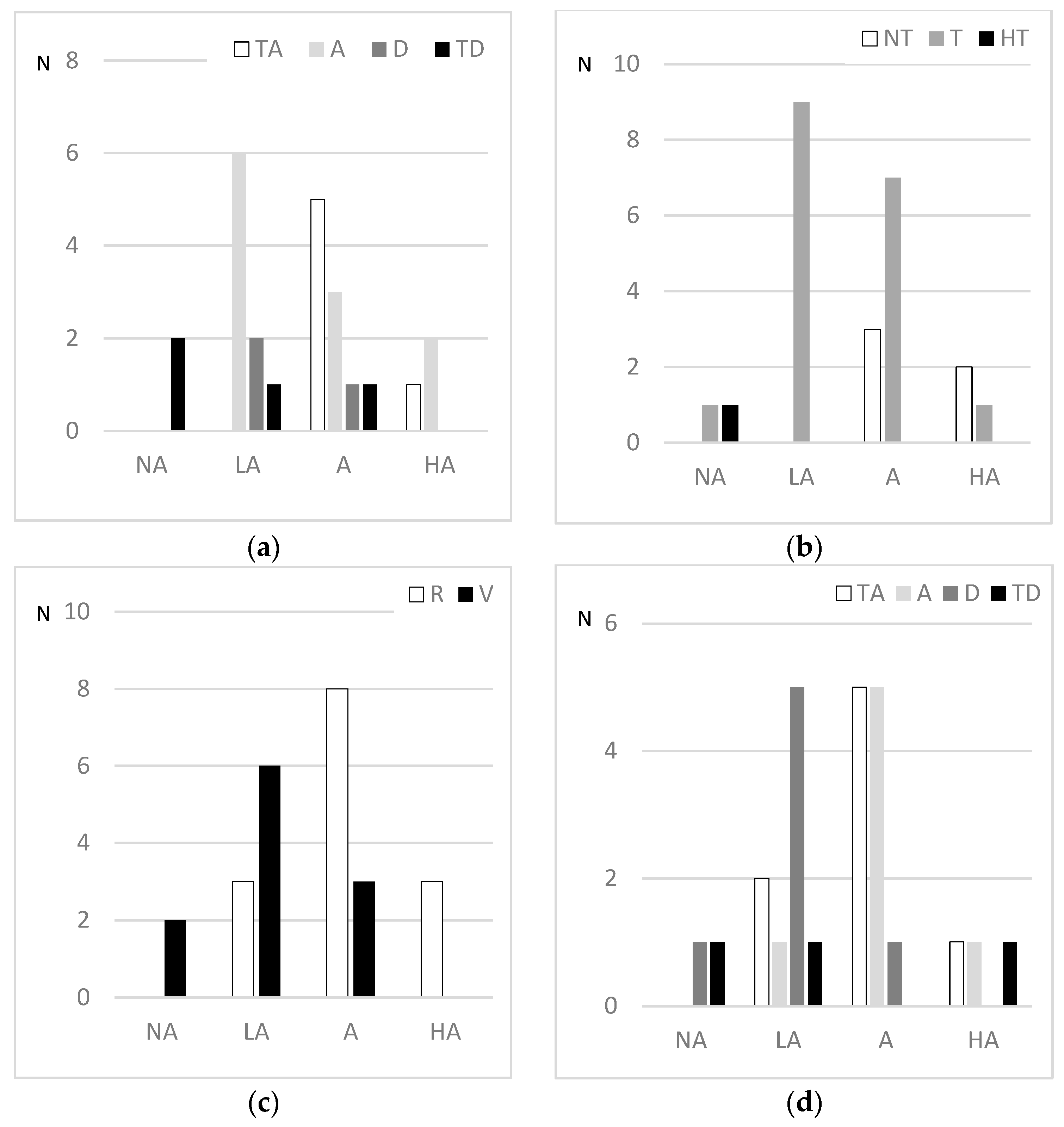

Regarding exploratory behaviour presented during the novel object transposition test and behaviours during the forced human approach and manipulation test at navel treatment (

Table 2), foals that were less reactive and that presented less tickling and the foals that during the forced human approach and manipulation test at haltering were more relaxed and less reactive correlated to foals that were more active and focused during the novel object transposition test.

Figure 1 illustrates how these correlations took place.

Figure 3.

Comparison between exploratory behaviour during novel object transposition test and (a) reactivity at first navel treatment; (b) tickle at first navel treatment; (c) alertness at first haltering session; (d) reactivity at first haltering session; N = number of observations; NA = no activity, LA = low activity, A = active, HA = high activity; TA = totally accepts management, A = mostly accepts management, D = don’t accept management at some point, TD = don’t accept management at all.

Figure 3.

Comparison between exploratory behaviour during novel object transposition test and (a) reactivity at first navel treatment; (b) tickle at first navel treatment; (c) alertness at first haltering session; (d) reactivity at first haltering session; N = number of observations; NA = no activity, LA = low activity, A = active, HA = high activity; TA = totally accepts management, A = mostly accepts management, D = don’t accept management at some point, TD = don’t accept management at all.

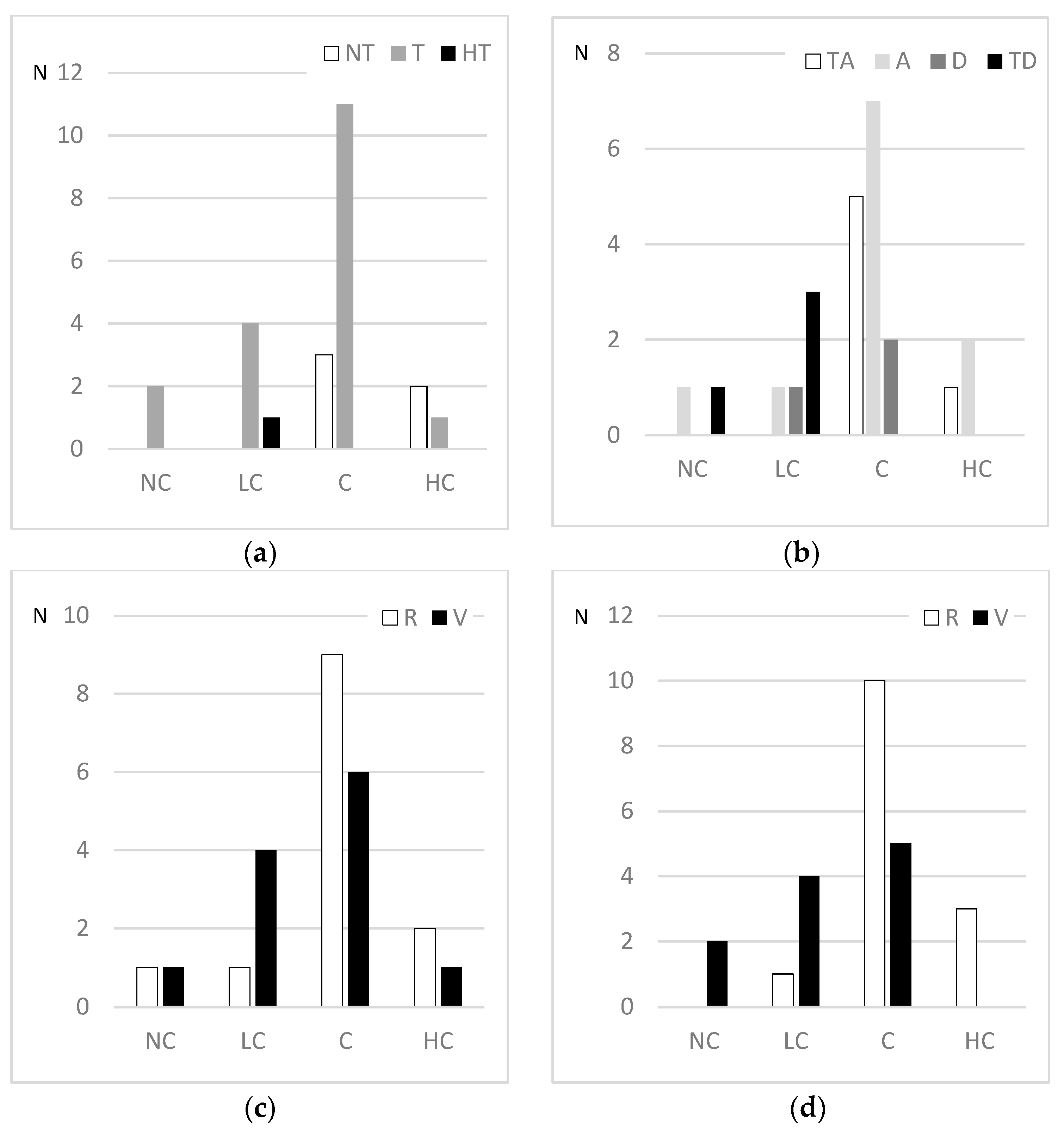

3.2. Confidence to transpose the novel object

The Spearman correlations between the behavioural parameter confidence to transpose the novel object and the behaviour showed by foals during the forced human approach and manipulation test at the navel and at haltering are shown in

Table 2. Foals that showed greater confidence at transposing were positively correlated to foals that showed less tickle and greater acceptance of human approximation, manipulation, or contention during navel treatment. Confidence to transpose tended to correlate to more relaxed foals at navel treatment and more relaxed foals at haltering.

Figure 4 illustrates these correlations.

3.3. Transposition style

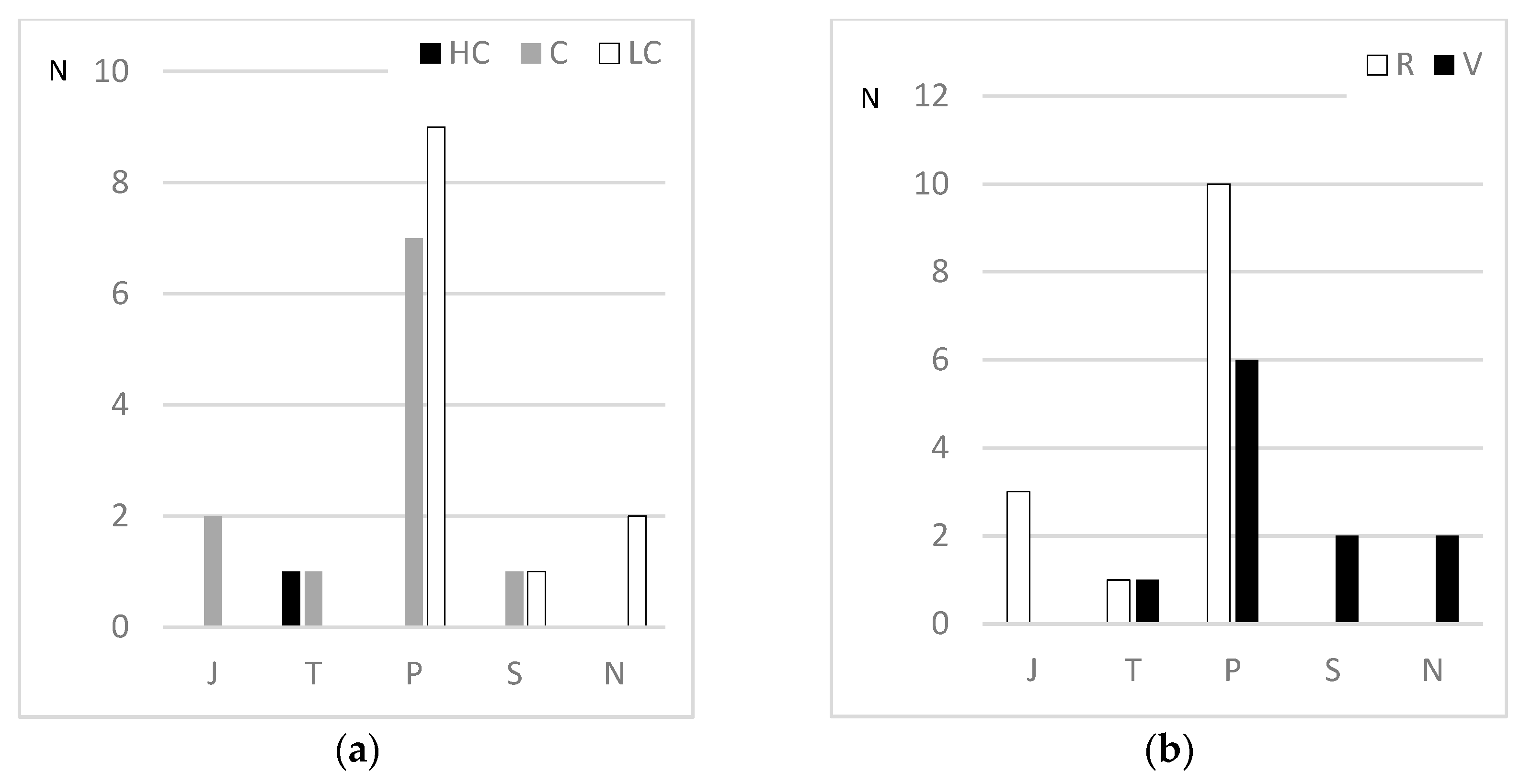

The greater transposition efficiency was positively correlated with foals that showed greater interest in humans during navel treatment and were more relaxed during haltering (Tabel 2). These correlations are shown in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

Our study pointed out that it is possible to use behaviours presented by foals in routine handling management as behaviour indicators when they grow older. We also found consistency between behaviours addressed subjectively between different tests and other foals' ages, consistent with several studies detailed below. Seaman, Davidson and Waran [

4] highlighted an aspect of this research when considering foals raised together (thus exposed to the same environment) that it permits predict future behavioural responses more accurately when compared to foals exposed to different breeding environments. At least part of the obtained results may be related to this statement.

The published data that were found addressing foal behaviours over time, they evaluated the effects of training performed when younger (usually at birth or weaning) and correlated it with behaviours presented in tests when the foals were older [4,16-19]. In other words, we didn't find any research evaluating behaviours during real farm situations, nor evaluating foals before they are trained, and even less evaluating these behaviours at different ages.

Maybe for the first time, it was presented data considering real farm situations to evaluate the behaviours of young horses, indicating that since the first day of the life of a foal, during the first interaction between humans and horses, it was possible to make inferences about its personality and future behaviour, which could be of practical value, by identifying individual variability at a very young age, and, with that, addressing particular needs and potentialities, offering training and handling that allow respecting and polishing the personality of each foal, helping to identify activities and human personalities more suited to the horse's personality, providing nurturing of the human-horse relationship and animal well-being.

It is also interesting to note that the kind of correlations obtained in this research indicates that the utilised methodology successfully discriminated similar behavioural parameters considered in other studies, usually with a more objective method.

The correlations found between different behaviours point to similar aspects of the personality of horses (

Table 2,

Figure 3). The various behavioural parameters registered may represent in part (or an association) between fear and gregariousness. Seaman, Davidson and Waran [

4] reported consistency in the behavioural responses obtained in arena tests, indicating that these can be used to predict equine temperament. In this sense, arena tests reveal how gregarious horses are, while tests such as novel object and transposition tests reflect the inherent fear in horses [

3]. Lansade, Bouissou and Erhard [

7] understands that transposition tests also indicate fear in horses. Górecka-Bruzda et al [

8] stated that tests of reactivity to humans also seem related to escape and feelings of self-preservation (usually triggered by fear of something).

The magnitude and direction of the correlations obtained in this research (

Table 2) were close to most studies with horses that addressed correlations between the same or similar behaviours to those evaluated in this research. Górecka-Bruzda et al. [

8] presented Spearman correlations corresponding to reactivity at management and novel object of 0.39 and between reactivity at management and fear of 0.36, indicating that these tests would measure similar characteristics.

Christensen et al. [

12] presented results approaching ours regarding the correlation between exploratory behaviour and alertness, with more relaxed horses showing more exploratory behaviours, presenting correlation values of rs = -0.42 at five months of age and rs = -0.40 when at one year old. In addition, they provided a Spearman correlation of rs = -0.49 between exploratory behaviour and learning, with better learning related to more exploratory individuals. This result is likely due to less fear or gregariousness characterising more exploring horses if we consider results presented by [

15], showing that the horse's learning capacity increased as it became more relaxed.

In this research, we correlated different behaviours at three ages of foals. Reactivity is the most correlated with exploratory behaviour among the assessed ages (

Table 2,

Figure 3). Tickle is a good indicator at birth of exploratory behaviour, whereas alertness may be a good indicator of exploratory behaviour at haltering, near weaning time.

Maintenance of behaviours throughout the development of foals has been reported by other authors, such as [

6], who published Spearman correlations corresponding to reactivity among foals at eight months and 1.5 years of age of the order of rs = 0.4 for Welsh ponies and rs = 0.68 for Anglo-Arab horses. Continuing the study of this group of horses, [

7] showed a Spearman correlation of rs = 0.53 to rs = 0.70 between eight-month-old and 1.5-year-old foals for alertness in the exploration test and a correlation of rs = 0.36 in the novel object test. Still with the same group of animals, [

5] reported a Spearman correlation of rs = 0.5 between 1.5- and 2.5-year-old foals regarding alertness during the separation test. Christensen et al. [

12] also reported a correlation between alertness (rs = 0.66) between 5-month-old and one-year-old foals. Comparing these same ages, they found a Spearman correlation of rs = 0.43 for exploratory behaviour. Evaluating young stallions, [

10] reported a similar result for exploratory behaviour, with a correlation of rs = 0.47 between five months and one year of age and rs = 0.57 between five months old and 3.5 years of age.

The correlation between confidence to transpose and alertness during navel management possibly discriminated against more relaxed and curious horses in the face of unknown situations or horses that, in challenging situations, manage to remain relaxed and focused on exploring the surroundings or even, in the case of alertness at haltering management, may indicate that the horse has learned to relax in unfamiliar situations. For horses developed using routine managements that stimulate the horse to keep the focus on humans associated with their relaxation and, therefore, establishes confidence in humans by the horses, as was the case with the horses evaluated in this study, the proximity of humans may have contributed to 72% of the foals have crossed the novel object with confidence or high confidence—similar data found in the literature point in the same direction. Christensen, Beblein and Malmkvist [

10] conclude that it is possible to predict future fearfulness by measuring the level of alertness towards novel objects at an early age (before weaning). Similar values of Spearman correlations were presented by Wolf +2 (1997), who reported that more emotional horses took longer to transpose a novel object (rs = 0.48) and remained more distant from the novel object (rs = 0.59). Subjective measures of horse personality, presented by [

9], using questionnaires answered by owners obtained, pointed out that extroverted horses were correlated to lower novel object transposition time (rs = 0.29) and refusal to transpose (rs = 0.48).

Resembling the association between confidence to transpose and alertness, reactivity at the first interaction with humans (during navel treatment,

Table 2,

Figure 4) possibly discriminated less fearful or more curious foals in unfamiliar and challenging situations. Górecka-Bruzda et al. [

8] reported a correlation corresponding to reactivity and novel object transposition a little lower than that obtained in this research (rs = 0.37). Considering correlations between behavioural tests and subjective measures of horse personality, [

9] presented a Spearman correlation of rs =0.27 comparing reactivity and neuroticism.

The observation that foals with more confidence to transpose novel object were correlated with less tickling during the first navel treatment (

Table 2,

Figure 4) may indicate fewer sensitive horses and horses less predisposed to react with fear or trying to escape from unknown and potentially threatening situations.

As with exploratory behaviour, the occurrence or maintenance of behaviours was also reported throughout the foal's development. Christensen, Beblein and Malmkvist [

10] found consistency regarding correlation of fear reactions throughout the development of young stallions, with alertness correlations between five months and one year of life (rs = 0.66), between five months and three and a half years (rs = 0.68) and between one year and three and a half years (rs = 0.68). Reporting a lower value, [

7] also found stability of confidence to transpose between eight months old foals and yearling horses (rs = 0.50 to rs = 0.71).

The correlation between transposition style and interest in humans at navel treatment indicated that foals with less willingness to transpose novel object corresponded to foals less attentive to humans (

Table 2,

Figure 5). The lack of interest in humans stems from fear of unknown things, whether humans or novel objects.

Alertness at haltering is also related to fearless, correlated foals that passed the novel object with greater energy with more readiness to transpose and more relaxed foals (

Table 2,

Figure 5). It would be interesting to compare the behaviours presented in the management routines evaluated with sports and work performance.

Considering the understanding of many researchers that arena, novel object and transposition tests measure aspects of fear and gregariousness, both aspects that influence safety, human-horse relationship and animal well-being, the correlations obtained in behaviours presented during handling of routine, such as alertness, reactivity and tickle could be used as early indicators of equine personality. Special attention could be given to more vigilant, reactive, and ticklish foals, offering training and handling focused on relaxation and confidence towards humans. Studies focusing on different training strategies' effects on equine personalities would be interesting.

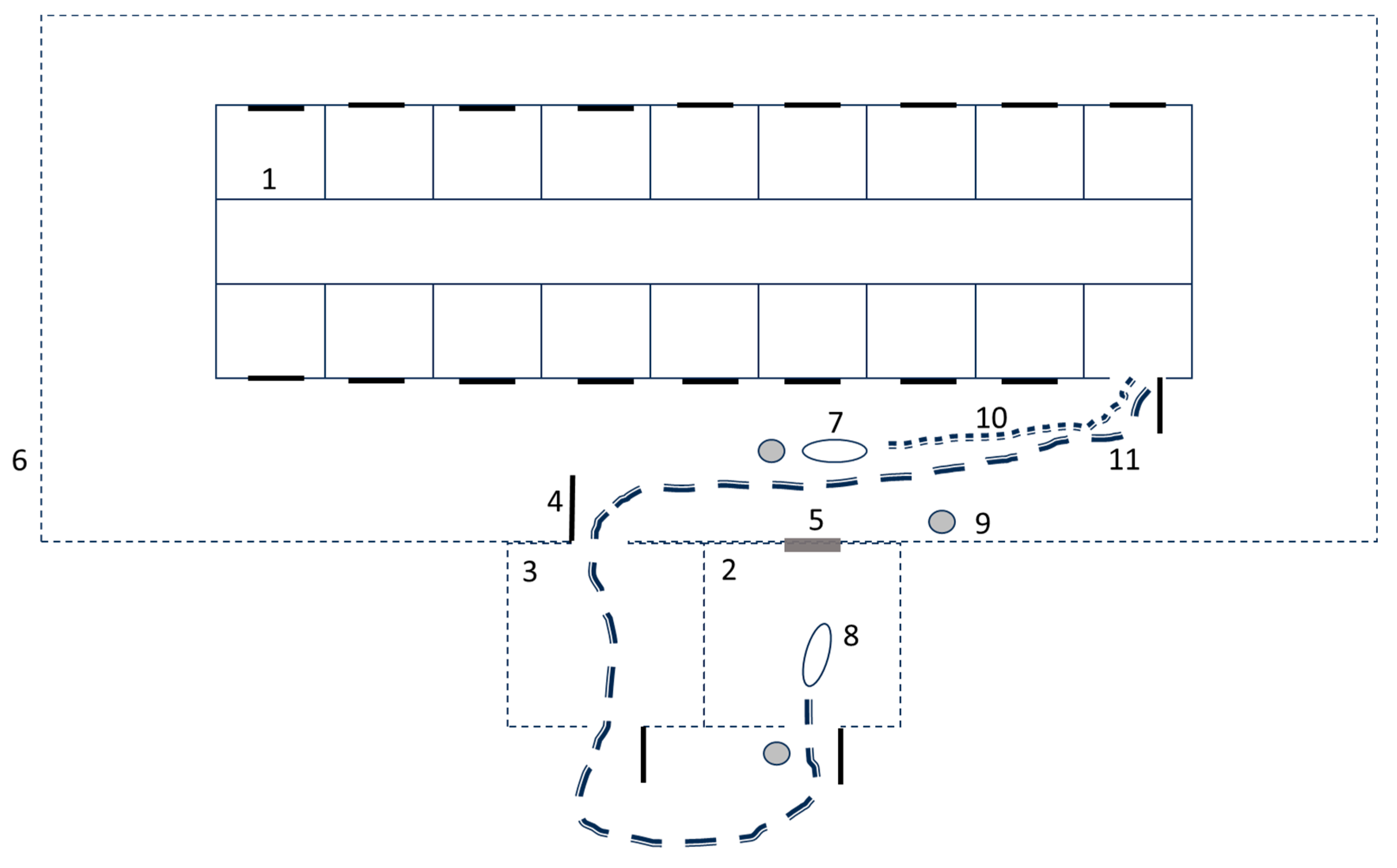

Figure 1.

Diagram of the distribution of experimental plan; 1 = boxes (weaning, haltering), 2 =management arena #1 (navel treatment, novel object transposition test), 3 = management arena #2, 4 = door, 5 = novel object, 6 = wood and wire fence, 7 = companion foal, 8 = test foal, 9 = human, 10 = companion foal path, 11 = test foal path.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the distribution of experimental plan; 1 = boxes (weaning, haltering), 2 =management arena #1 (navel treatment, novel object transposition test), 3 = management arena #2, 4 = door, 5 = novel object, 6 = wood and wire fence, 7 = companion foal, 8 = test foal, 9 = human, 10 = companion foal path, 11 = test foal path.

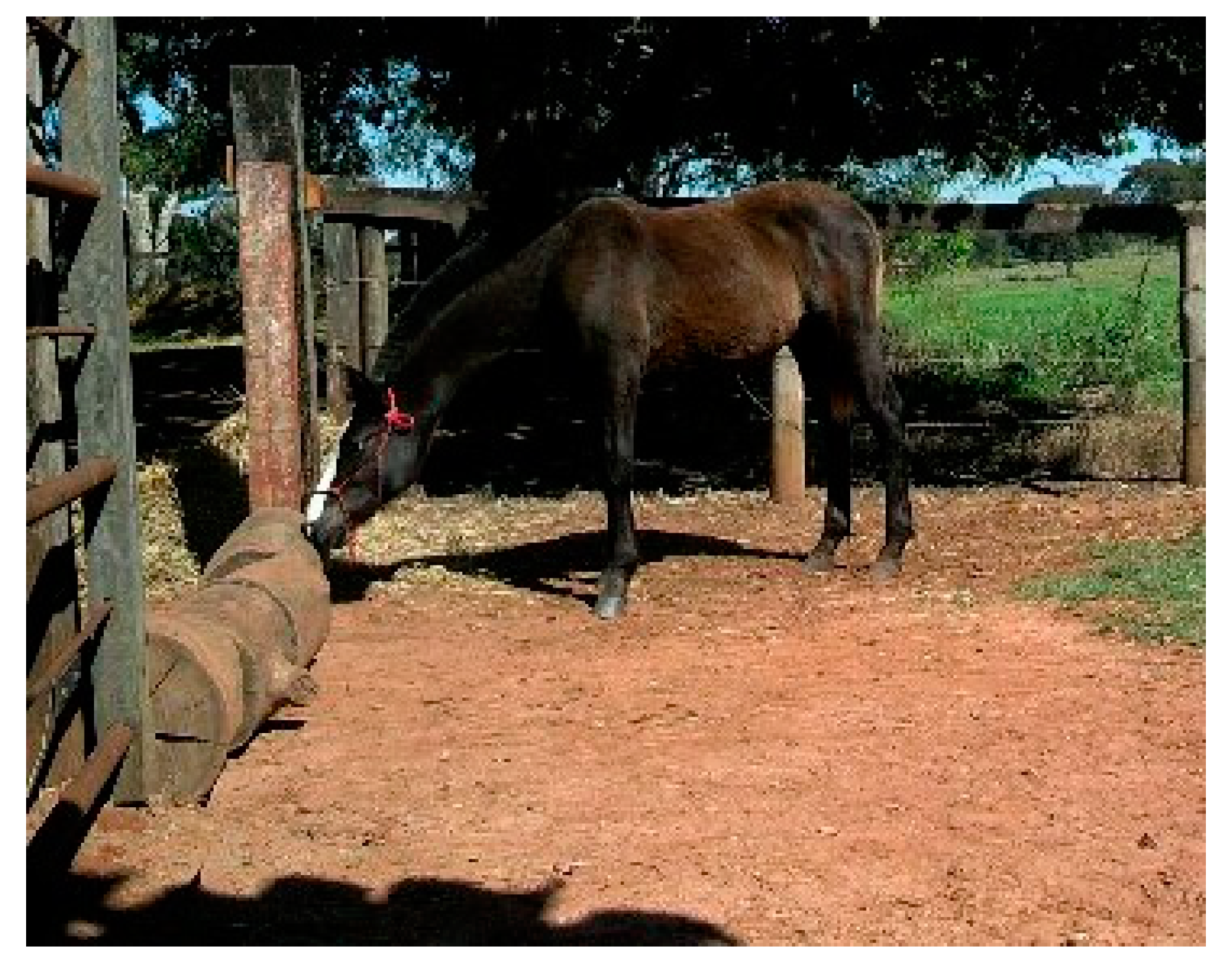

Figure 2.

Photograph presenting the novel object to be transposed, with a foal touching the object with its nose.

Figure 2.

Photograph presenting the novel object to be transposed, with a foal touching the object with its nose.

Figure 4.

Comparison between confidence behaviour during novel object transposition test and (a) tickle at first navel treatment; (b) reactivity to humans at first navel treatment; (c) alertness at first navel treatment; (d) alertness at first haltering session; N = number of observations; NC = not confident, LC = low confidence, C = confident, HC = high confidence; NT = no tickle, T = tickle, HT = high tickle; TA = totally accepts management, A = mostly accepts management, D = don’t accept management at some point, TD = don’t accept management at all; R = relaxed, V = vigilant.

Figure 4.

Comparison between confidence behaviour during novel object transposition test and (a) tickle at first navel treatment; (b) reactivity to humans at first navel treatment; (c) alertness at first navel treatment; (d) alertness at first haltering session; N = number of observations; NC = not confident, LC = low confidence, C = confident, HC = high confidence; NT = no tickle, T = tickle, HT = high tickle; TA = totally accepts management, A = mostly accepts management, D = don’t accept management at some point, TD = don’t accept management at all; R = relaxed, V = vigilant.

Figure 5.

Comparison between transposition style during novel object transposition test and (a) interest in human at first navel treatment; (b) alertness at first haltering session; N = number of observations; J = jumps over novel object, T = trots over novel object, W = walks over novel object, S = steps on novel object; N = didn’t transpose novel object; HC = high curiosity, C = curious, LC = low curiosity; R = relaxed, V = vigilant.

Figure 5.

Comparison between transposition style during novel object transposition test and (a) interest in human at first navel treatment; (b) alertness at first haltering session; N = number of observations; J = jumps over novel object, T = trots over novel object, W = walks over novel object, S = steps on novel object; N = didn’t transpose novel object; HC = high curiosity, C = curious, LC = low curiosity; R = relaxed, V = vigilant.

Table 1.

Ethogram of registered behavioural parameters.

Table 1.

Ethogram of registered behavioural parameters.

| Behavioural Parameter |

When Observed |

Description |

| Interest in Human |

Navel treatment; Haltering |

Pays attention to the human person(s) interacting with the foal during most of the time (Score 1; HC); Pays attention to the human person(s) interacting with the foal sometimes (Score 2; C); Pays minimal attention or didn’t pay attention to the human person(s) interacting with the foal (Score 3; LC). |

| Alertness |

Navel treatment; Haltering |

Vigilant: no movement or abrupt movements, tensioned muscles of the body, elevated neck (Score 1; V); Relaxed: smooth movements, relaxed body musculature, neck leveled with withers or lowered (Score 2; R). |

| Tickle |

Navel treatment; Haltering |

Presents constant skin shakings when touched by humans during management (Score 1; HT); Presents occasional skin shakings when touched by humans during management (Score 2; T); Doesn’t present skin shakings when touched by humans during management (Score 3; LT). |

| Reactivity |

Navel treatment; Haltering |

Totally accepts human approach and don’t try to escape from contention or manipulation (Score 1; TA); Mostly accepts or accepts human approach and try to escape mildly from contention and/ or manipulation (Score 2; A); Doesn’t accepts human approach and manipulation and/ or contention at some moment of the procedure (Score 3; D); Doesn’t accepts approach, contention, and manipulation during the procedure (Score 4; TD). |

| Exploratory Behaviour |

Novel Object Transposition |

Not active, moves very little or is uninterested in the novel object (Score 1; NA); Low activity, moves little and/ or without Much interest in the novel object (Score 2; LA); Active, moves frequently and/ or interested in the novel object (Score 3; A); Higly active, moves continuously and/ or fully focused on the novel object (Score 4; HA). |

| Confidence to Transpose |

Novel Object Transposition |

No confidence, doesn’t transpose the novel object (Score 1; NC); Low confidence, approaches the novel object with reluctance, possibly moving away and approaching again, transposes the novel object (Score 2; LC); Confident; moves frequently and relaxed towards the novel object, possibly touching the nose to it, transposes the novel object (Score 3; C); High confidence; moves continuously and relaxed towards the novel object, possibly touching the nose to it, transposes de novel object (Score 4; HC). |

| Transposition Style |

Novel Object Transposition |

Jumps over the object (Score 1; J); Trots over the object (Score 2; T); Walks over the object (Score 3; W); Steps on the object (Score 4; S); Doesn’t transpose the object (Score 5; N). |

Table 2.

Spearman correlations between behavioural parameters presented during routine management (forced human approach and manipulation test at navel treatment and at haltering) and during novel object transposition test (NOT).

Table 2.

Spearman correlations between behavioural parameters presented during routine management (forced human approach and manipulation test at navel treatment and at haltering) and during novel object transposition test (NOT).

| Behavioural Parameters |

Exploratory Behaviour (NOT) |

Confidence to Transpose

(NOT) |

Transposition Style

(NOT) |

| Alertness (navel) |

NS |

0.39 (P=0.06; N=23) |

NS |

| Reactivity (navel) |

-0.50 (P=0.01; N=23) |

-0.51 (P=0.01; N=23) |

NS |

| Interest in Humans (navel) |

NS |

NS |

0.48 (P=0.02; N=24) |

| Tickle (navel) |

0.60 (P=0.002; N=24) |

0.49 (P=0.01; N=24) |

NS |

| Alertness (haltering) |

0.56 (P+0.03; N=25) |

0.57 (P=0.03; N=25) |

-0.48 (P=0.02; N=25) |

| Reactivity (haltering) |

-0.42 (P=0.04; N=25) |

NS |

NS |

| Interest in Humans (haltering) |

NS |

NS |

NS |

| Tickle (haltering) |

NS |

NS |

NS |