Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

03 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

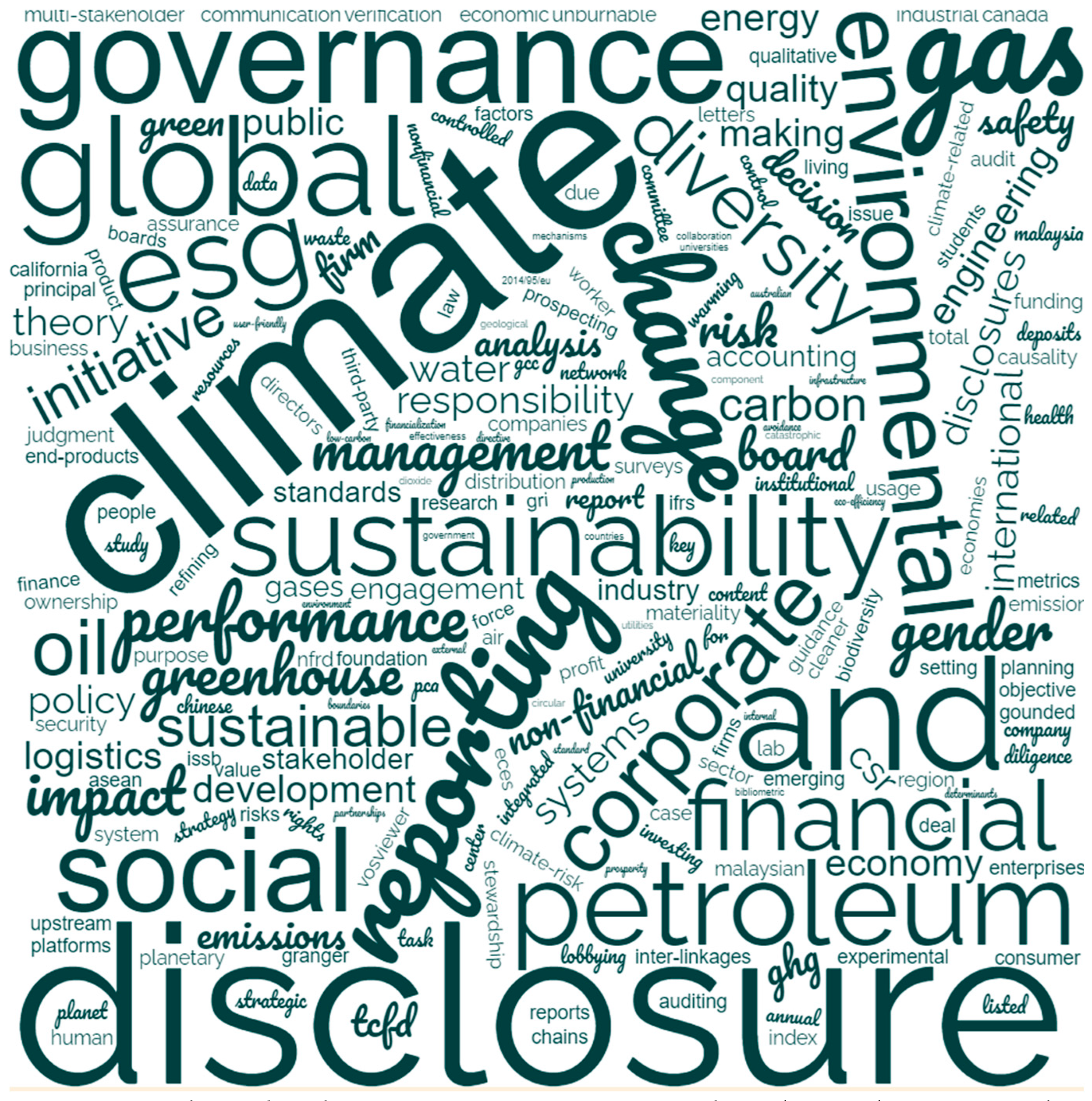

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Sustainability Reporting

2.1. Sustainability Reporting, Climate Change, and Energy

2.2. Reported Board Characteristics Effects

3. Methodology

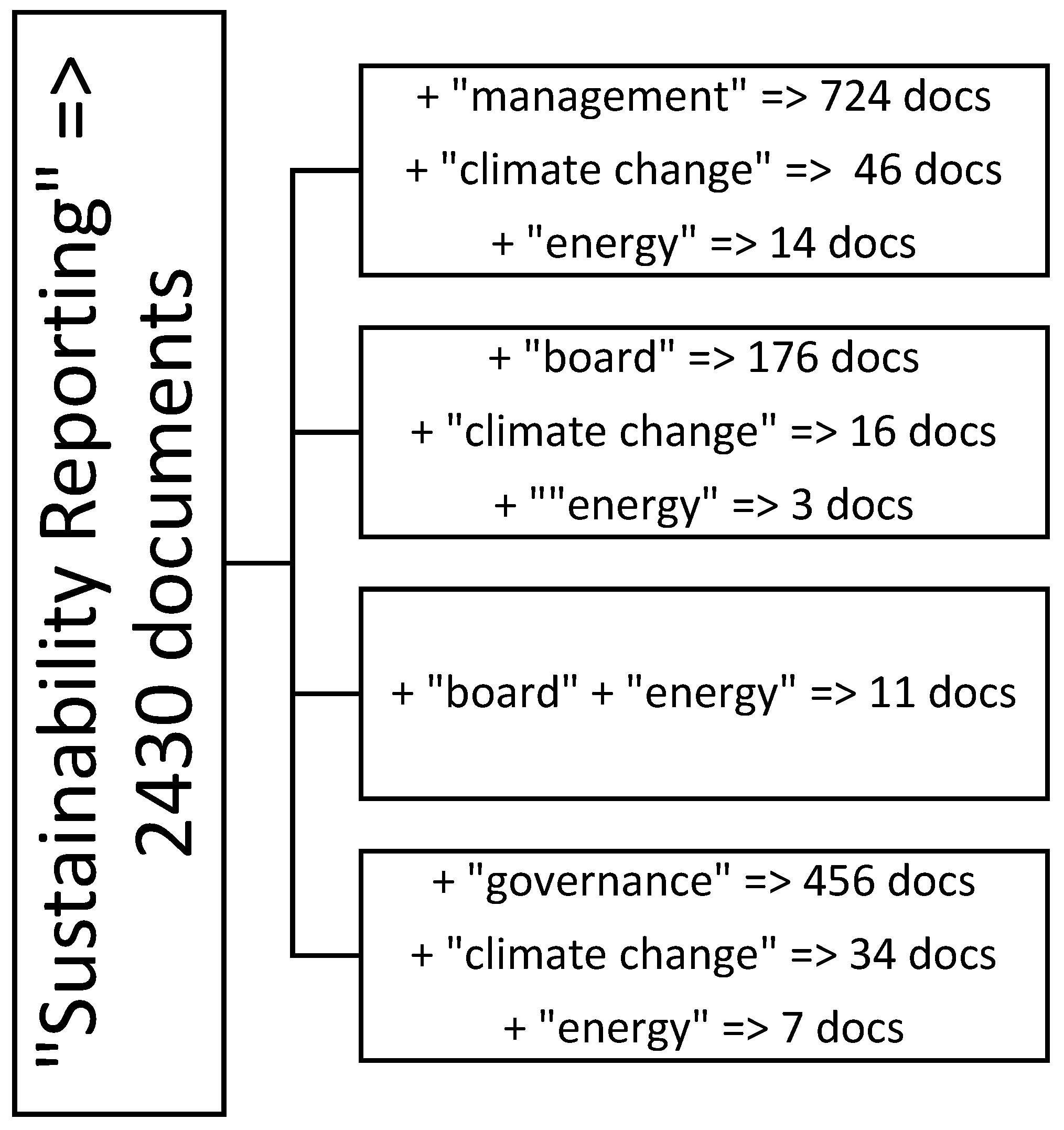

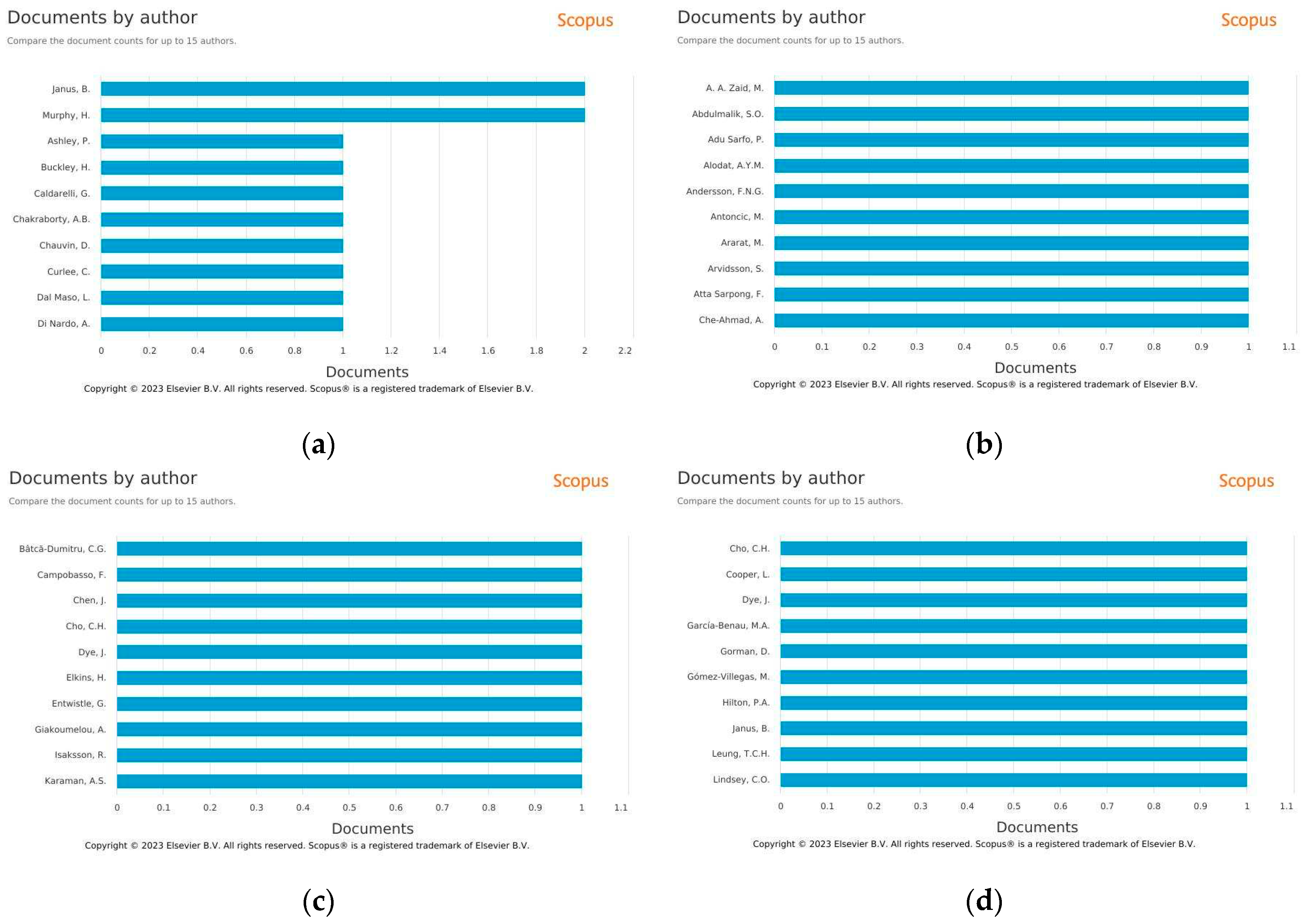

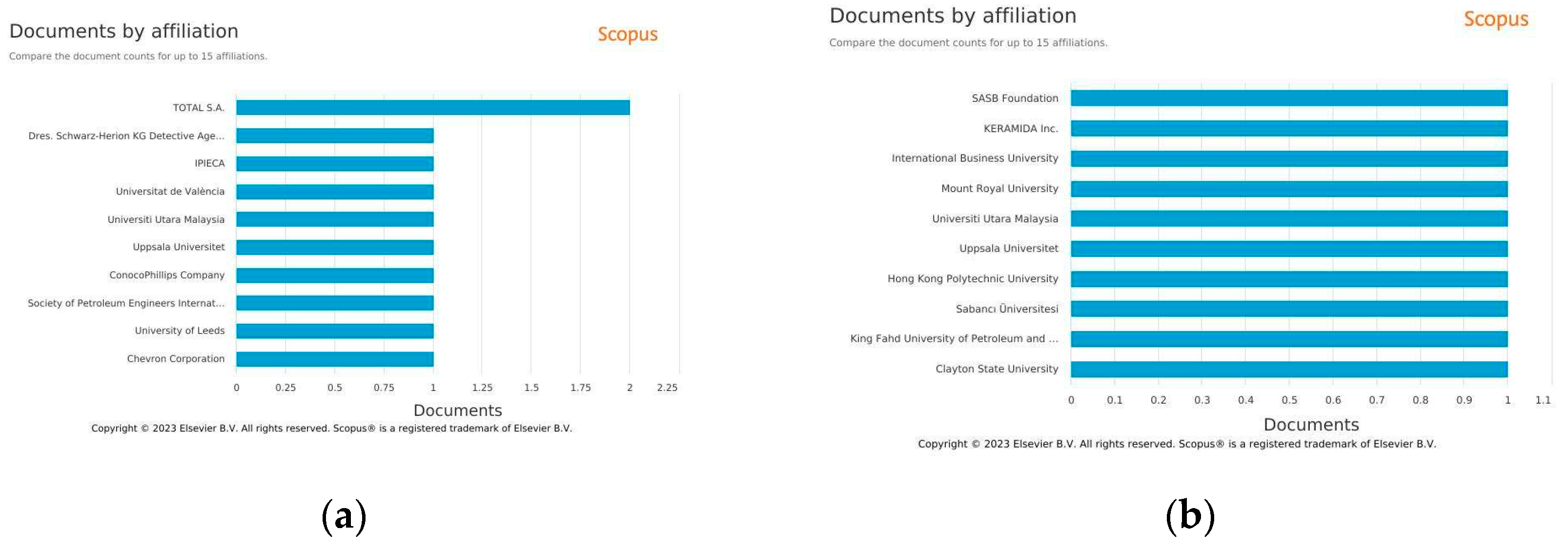

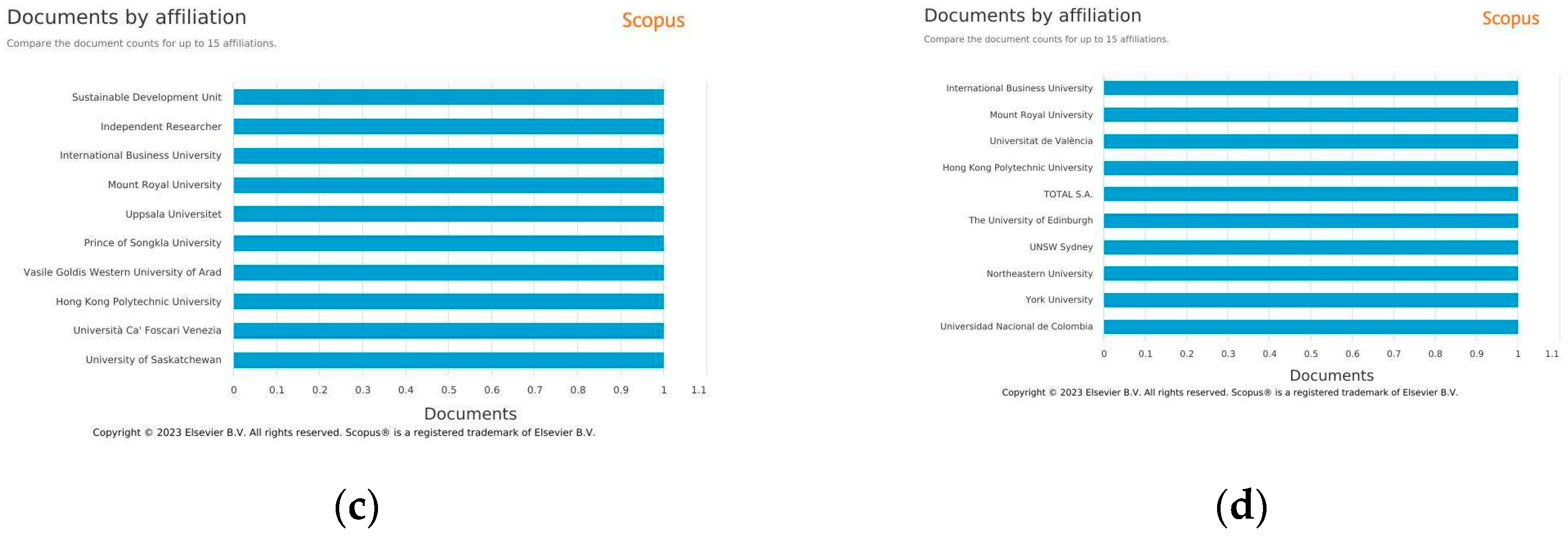

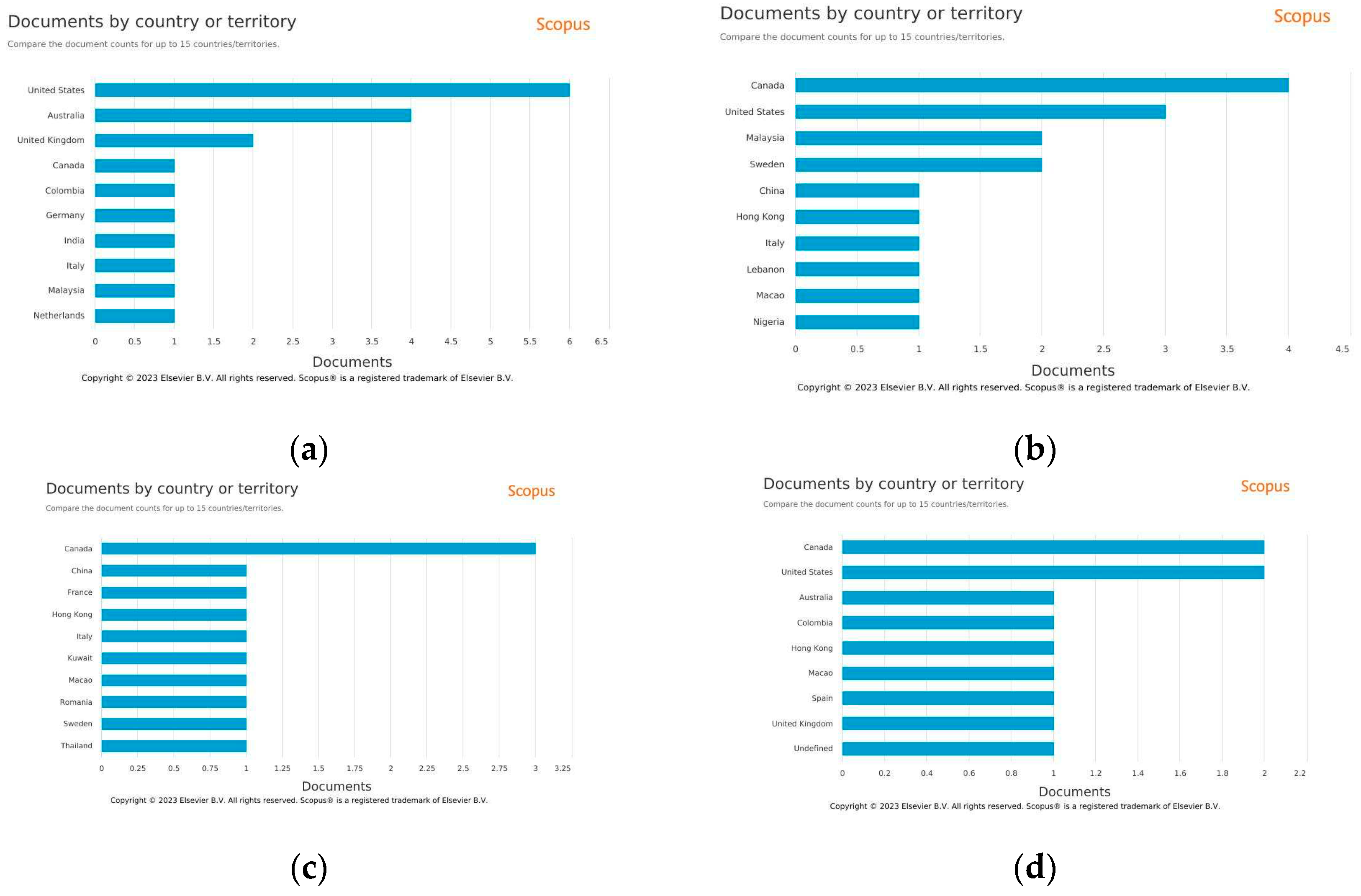

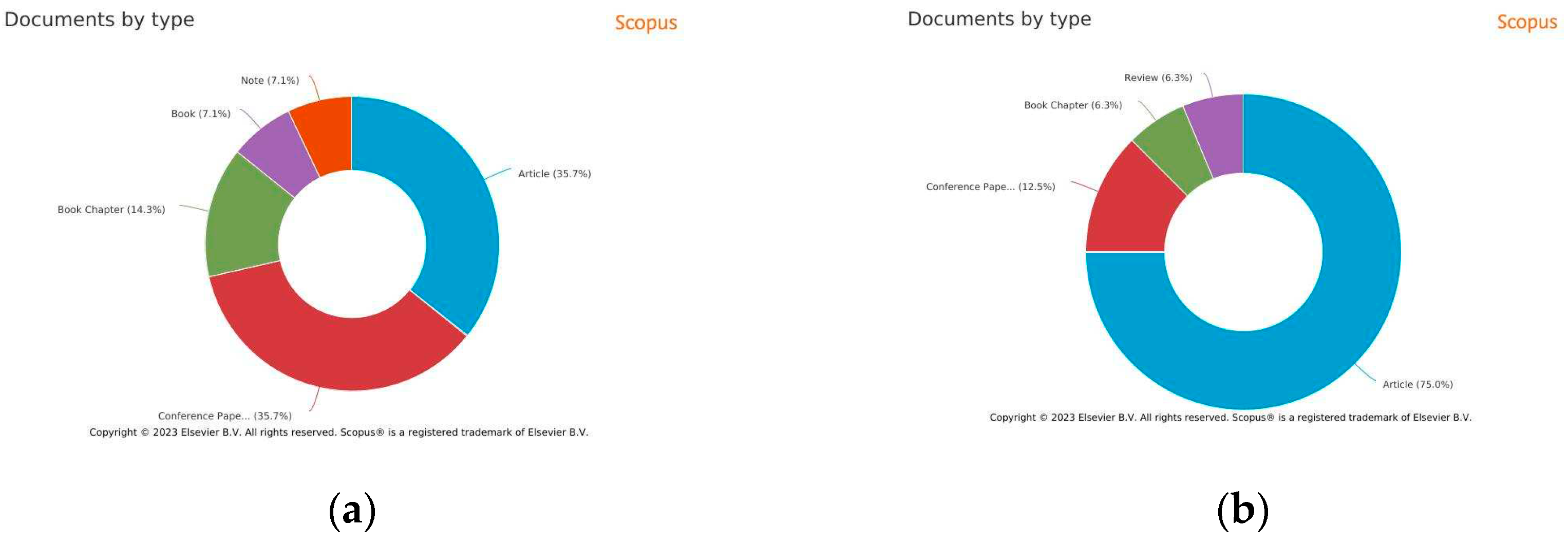

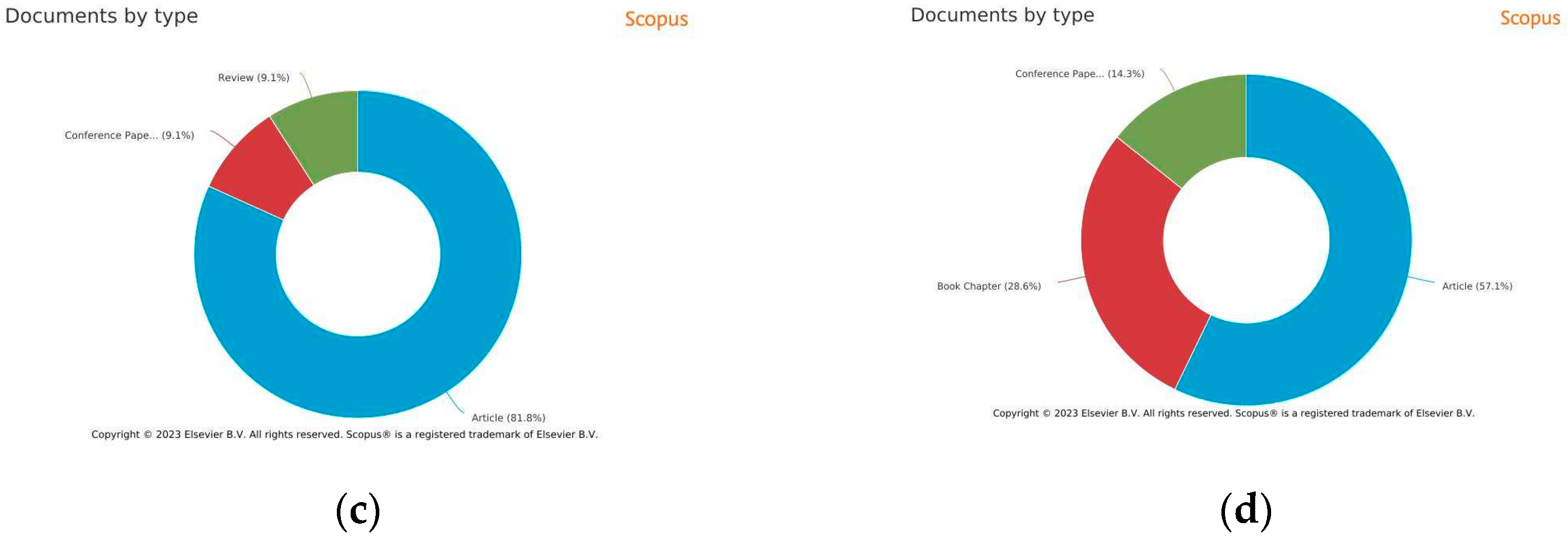

4. Results: Analysis of Bibliometric Data

5. Discussion

5.1. Bibliographic Sample Analysis

5.2. The Role of Governance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E. CSR practices and consumer perceptions. J Bus Res 2013, 66, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winit, W. , Ekasingh, E., Sampet, J. How Disclosure Types of Sustainability Performance Impact Consumers’ Relationship Quality and Firm Reputation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Loorbach, D.; Hörisch, J. Managing entrepreneurial and corporate contributions to sustainability transitions. Bus Strat Env 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual Rev Env Resourc 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winit, W.; Kantabutra, S. Enhancing the Prospect of Corporate Sustainability via Brand Equity: A Stakeholder Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilience and performance. Strat Lead 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Loock, M.; Cerruti, J.; Muyot, M. Sustainability: How stakeholder perceptions differ from corporate reality. Calif Manag Rev 2012, 55, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustia, D.; Harymawan, I.; Permatasari, Y. Board diversity, sustainability report disclosure and firm value. Global Bus Rev 2022, 23, 1520–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorelli, M.F.; García-Sánchez, I.M. Critical mass of female directors, human capital and stakeholder engagement by corporate social reporting”, Corp Soc Resp Env Manag 2020, 27, 204–221.

- Erin, O.A.; Bamigboye, O.A.; Oyewo, B. Sustainable development goals (SDG) reporting: an analysis of disclosure. J Account Emerg Econ 2022, 12, 761–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyigbah, E.; Kong, Y.; Edziah, B.K.; Ahoto, A.T.; Ahiaku, W.S. Board Characteristics and Corporate Sustainability Reporting: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braegelmann, K.A.; Ujah, N.U. Gender matters: market perception of future performance. Manag Fin 2020, 46, 1247–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Azevedo, T.-C. CEO ability and sustainability disclosures: the mediating effect of corporate social responsibility performance. Corp Social Resp Env Manag 2020, 27, 1565–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oware, K.M.; Amoako, G.K.; Halidu, O.B. Does the gender of board members influence the choice of sustainability report format of listed firms? Empirical evidence from India. Manag Fin 2023, 49, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.W.; Walls, J.L.; Dowell, G.W.S. Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strat Manag J 2014, 35, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Ding, D.K.; Charoenwong, C. Investor reaction to women directors. J Bus Res 2010, 63, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadiyappa, N.; Jyothi, P.; Sireesha, B.; Hickman, L.E. CEO gender, firm performance and agency costs: evidence from India. J Econ Studies 2019, 46, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex (2023). DIRECTIVE 2014/95/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 22 October 2014, amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014L0095.

- UN (2023). United Nations Environment Programme. Corporate sustainability reporting. Available at: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/responsible-industry/corporate-sustainability.

- Kantabutra, S. Measuring corporate sustainability: A Thai approach. Meas Bus Exc 2014, 18, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.W.; Leung, T.C.H.; Yu, T.-W.; Cho, C.H.; Wut, T.M. Disparities in ESG reporting by emerging Chinese enterprises: evidence from a global financial center. Sustainability Account Manag Policy J 2023, 14, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalbaki, S.; Guzmán, F. A consumer-perceived consumer-based brand equity scale. J Brand Manag 2016, 23, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Big Shifts, Small Steps. Survey of Sustainability Reporting. 2022. Available online: https://home.kpmg/th/en/home/insights/2022/09/survey-of-sustainability-reporting-2022.html (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2003). Sustainable Development Reporting: Striking the Balance. Heemskerk, B., Pistorio, P., & Scicluna, M. (2002). World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

- Al-Shaer, H.; Albitar, K.; Hussainey, K. Creating sustainability reports that matter: an investigation of factors behind the narratives. J Applied Account Res 2022, 23, 738–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampone, G.; Nicolò, G.; Sannino, G.; De Iorio, S. Gender diversity and SDG disclosure: the mediating role of the sustainability committee. J Applied Account Res 2022, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Rashid, K. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: An empirical evidence from commercial banks (CB) of Pakistan. Qual Quan 2014, 48, 2501–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, N.; Cajias, M.; Bienert, S. The value contribution of sustainability reporting—An empirical evidence for real estate companies. J Fin Risk Perspec 2015, 4, 190–205. [Google Scholar]

- Githaiga, P.N. Sustainability reporting, board gender diversity and earnings management: evidence from East Africa community. J Bus Socio-econ Dev 2023, Vol. ahead-of-print, No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Daniel-Vasconcelos, V.; Ribeiro, M.d.S.; Crisóstomo, V.L. Does gender diversity moderate the relationship between CSR committees and Sustainable Development Goals disclosure? Evidence from Latin American companies. RAUSP Manag J 2022, 57, 434–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón, A.; Kazemikhasragh, A.; Cicchiello, A.F.; Monferrá, S. The Impact of Board Gender Diversity on Sustainability Reporting and External Assurance: Evidence from Lower-Middle-Income Countries in Asia and Africa. J Econ Issues 2022, 56, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Raza, A.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Morake, O. Examining the green factors affecting environmental performance in small and medium–sized enterprises: A mediating essence of green creativity. Frontiers Psych 2022, 13:1078203. [CrossRef]

- Ghardallou, W. Corporate Sustainability and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of CEO Education and Tenure. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, C.; Raina, R. Towards more sustainable future: Assessment of sustainability literacy among the future managers in India. Env Dev Sustainability 2021, 23, 15830–15856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorelli, M.-F.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. Trends in the dynamic evolution of board gender diversity and corporate social responsibility. Corp Soc Resp Env Manag 2021, 28, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, R.; Yousfi, O.; Loukil, N.; Abdelwahed, O. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from France. J Bus Ethics 2021, 173, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, S.F.A.; Abdullah, D.F.; Elamer, A.A.; Abueid, R. Nudging toward diversity in the boardroom: A systematic literature review of board diversity of financial institutions. Bus Strat Env 2021, 30, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osemene, O.F.; Adinnu, P.; Fagbemi, T.O.; Olowookere, J.K. Corporate governance and environmental accounting reporting in selected quoted African companies. Global Bus Rev 2021, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.W.; Subhan, Q.A. Impact of board diversity and audit on firm performance. Cog Bus Manag 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. J Bus Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Periasamy, V.; Zulkafli, A.H. Determinants of climate change disclosure by developed and emerging countries in Asia Pacific. Sust Develop 2014, 22, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Fin Manag 2006, 35, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, C.; Michelon, G.; Raggi, D. Monitoring intensity and stakeholders’ orientation: How does governance affect social and environmental disclosure? J Bus Ethics 2013, 114, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongore, V.O.; Peter, O.; Ogutu, M.; Bosire, E.M. Board composition and financial performance: Empirical analysis of companies listed at the Nairobi securities exchange. Int J Econ Fin Issues 2015, 5, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D.A.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Fin Rev 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S.; Sealy, R.; Singh, V. Women Directors on Corporate Boards: A Review and Research Agenda. Corp Gov Int Rev 2009, 17, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, A.; Ahmed, K.; Mather, P. Board Diversity and Financial Performance in the Top 500 Australian Firms. Austral Account Rev 2015, 25, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-s.; Lai, W.-h.; Yen, S.-h. Boardroom Diversity and Operating Performance: The Moderating Effect of Strategic Change. Emerg Mark Fin Trade 2019, 55, 2448–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Byron, K. Women on boards and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis. Acad Manag J 2015, 58, 1546–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Rahman, N.; McQuillen, C. From board composition to corporate environmental performance through sustainability-themed alliances. J Bus Ethics 2015, 130, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C. , Rahman, N.; Rubow, E. Green governance: Boards of directors’ composition and environmental corporate social responsibility. Bus Soc 2011, 50, 189–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Faff, R. Impact of board size and board diversity on firm value: Australian evidence. Corp Own Control 2007, 4, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryman, A.A.; Fernando, G.D.; Tripathy, A. Do gender differences persist? An examination of gender diversity on firm performance, risk, and executive compensation. J Bus Res 2016, 69, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, I.; Saeed, B.B. Does board diversity affect quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure? Evidence from Pakistan. Corp Social Resp Env Manag 2019, 26, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khan, I.; Senturk, I. Board diversity and quality of CSR disclosure: Evidence from Pakistan. Corp Gov (Bingley) 2019, 19, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlotti, K.; Mazza, T.; Tibiletti, V.; Triani, S. Women in top positions on boards of directors: gender policies disclosed in Italian sustainability reporting. Corp Social Resp Env Manag 2019, 26, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Guo, X. The relationships between reporting format, environmental disclosure and environmental performance an empirical study. J Applied Account Res 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Mahmood, M. Determinants of GRI-based sustainability reporting: evidence from an emerging economy. J Account Emerg Econ 2019, 10, 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Al Farooque, O.; Momin, M.A.; Almotairy, O. Women in the boardroom and their impact on climate change related disclosure. Social Resp J 2017, 13, 828–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; Sousa-Filho, J.M.D. Board structure and environmental, social and governance disclosure in Latin America. J Bus Res 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katmon, N.; Mohamad, Z.Z.; Norwani, N.M.; Farooque, O.A. Comprehensive board diversity and quality of corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from an emerging market. J Bus Ethics 2019, 157, 447–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Yin, M. A female style in corporate social responsibility? Evidence from charitable donations. Int J Discl Gov 2018, 15, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls Martínez, M.D.C.; Cruz Rambaud, S.; Parra Oller, I.M. Gender policies on board of directors and sustainable development. Corp Social Resp Env Manag 2019, 26, 1539–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Fadli, A.; Sands, J.; Jones, G.; Beattie, C.; Pensiero, D. Board gender diversity and CSR reporting: evidence from Jordan. Austr Account, Bus Fin J 2019, 13, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristie, J. The power of three. Direc Boards 2011, 35, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mudiyanselage, R.N.C.S. Board involvement in corporate sustainability reporting: evidence from Sri Lanka. Corp Gov (Bingley) 2018, 18, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Said, R.; Shen, L.T.; Nahar, H.S.; Senik, R. Board compositions and social reporting: evidence from Malaysia. Int J Manag Fin Account 2018, 10, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Ríos, K. , García López, A.J. Bibliometrics, a useful tool within the field of research. J Basic Applied Psych Res 2022, 3, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Pattnaik, D. Forty-five years of Journal of Business Research: A bibliometric analysis. J Bus Res 2020, 109, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, AW. Two new kids on the block: How do Crossref and Dimensions compare with Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus and the Web of Science? Scientometrics 2019, 120, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Thelwall, M.; Orduna-Malea, E. Google Scholar, Microsoft Academic, Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, and OpenCitations’ COCI: A multidisciplinary comparison of coverage via citations. Scientometrics 2020, 126, 871–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlowe, J.; Clarke, A. Carbon accounting: A systematic literature review and directions for future research. Green Fin 2022, 4, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D. Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. J Cleaner Prod 2011, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, M.A.A. Accounting for Climate Change in Light of the IFRS Foundation Movements: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 2023, 621 LNNS, 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kordecki, G.S.; Grant, D.M. Sustainability Gains through Enhanced Reporting Requirements. Int J Bus 2023, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, N. The value of voluntary sustainability reporting. Bracing for Climate Change: Strategies for Mitigation and Resiliency Planning. Conference Proceedings 2020. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85084245132&partnerID=40&md5=3bd5e10301739d55ebd4c4cad53bfcc2. 8508. [Google Scholar]

- Jizi, M.; Nehme, R.; Melhem, C. Board gender diversity and firms' social engagement in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Equal Diver Incl 2022, 41, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macoskey, K.A. A survey of U.S. Industrial sustainability reports - Part 2. Proceedings of the Air and Waste Management Association's Annual Conference and Exhibition, AWMA, 2020-June. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85104844693&partnerID=40&md5=e4612461e3db4f20d0632bd69dd8c04b. 8510. [Google Scholar]

- Melles, G. Sustainability Reporting in Australian Universities: Case Study of Campus Sustainability Employing Institutional Analysis. World Sustainability Series 2020, 945–974. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, L.; Gorman, D. A Holistic Approach to Embedding Social Responsibility and Sustainability in a University—Fostering Collaboration Between Researchers, Students and Operations. World Sustainability Series 2018, 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Facchini, A.; Scala, A.; Lattanzi, N.; Caldarelli, G.; Liberatore, G.; Dal Maso, L.; Di Nardo, A. Complexity science for sustainable smart water grids. Commun Comp Info Science 2017, 708, 26–41. [Google Scholar]

- Vitolla, F.; Raimo, N.; Campobasso, F.; Giakoumelou, A. Risk disclosure in sustainability reports: Empirical evidence from the energy sector. Utilities Policy 2023, 82, art no 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, J.; McKinnon, M.; Van der Byl, C. Green Gaps: Firm ESG Disclosure and Financial Institutions’ Reporting Requirements. J Sustainability Res 2021, 3, e210006. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, H.; Janus, B. Managing HSE performance through sustainability reporting. Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE E and P Health, Safety, Security and Environmental Conference - Americas 2015, 284-292.

- Curlee, C.; Retzsch, W.; Robinson, N.; Edwards, G.; Hunter, D.; Krishna, P.; Granquist, M.; Gimelli, N.; Nordang, H.; Chauvin, D.; Buckley, H.; Romer, R. The oil & gas industry guidance on voluntary sustainability reporting: A major revision on the horizon. Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE International Conference on Health, Safety and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production 2010, 2, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A.B. Carbon management - The emerging paradigm for the oil industry. Proceedings - SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition 2007, 4, 2410–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, A.S.; Kilic, M.; Uyar, A. Green logistics performance and sustainability reporting practices of the logistics sector: The moderating effect of corporate governance. J Cleaner Prod 2020, 258, art no 120718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschnik, S.; Lomax, R.; Tennison, I. The transformation to environmentally sustainable health systems: The national health service example in England. Lakartidningen 2019, 116, 412. [Google Scholar]

- Antoncic, M. Why sustainability? Because risk evolves and risk management should too. J Risk Manag Fin Inst 2019, 12, 206–216. [Google Scholar]

- Trotman, A.J.; Trotman, K.T. Internal audit’s role in GHG emissions and energy reporting: Evidence from audit committees, senior accountants, and internal auditors. Auditing 2015, 34, 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, P.A. Carbon/Greenhouse Gas Transparency and Socially Responsible Investing. Green Trad Mark 2005, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Alzate, Y.M.; García-Benau, M.A.; Gómez-Villegas, M. Materiality assessment: the case of Latin American listed companies. Sustainability Account Manag Policy J 2021, 13, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petera, P.; Wagner, J.; Paksiova, R.; Krehnacova, A. Sustainability information in annual reports of companies domiciled in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. Eng Econ 2019, 30, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, P. A sustainability index for manufactured products? A conceptual paper. Aust J Env Manag 2014, 21, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, H.; Entwistle, G. A Canadian Response to the Pursuit of Global Sustainability Reporting Standards. Account Perspec 2023, 22, 7–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyantakyi, G.; Atta Sarpong, F.; Adu Sarfo, P.; Uchenwoke Ogochukwu, N.; Coleman, W. A boost for performance or a sense of corporate social responsibility? A bibliometric analysis on sustainability reporting and firm performance research (2000-2022). Cogent Bus Manag 2023, 10, 2220513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, F.N.G.; Arvidsson, S. Understanding, mapping and reporting of climate-related risks among listed firms in Sweden. Climate Policy 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.R.; Shao, C.; Chen, J. Approaches on the screening methods for materiality in sustainability reporting. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlethwaite, J. The politics of experimentation in climate change risk reporting: the emergence of the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB). Environ Politics 2015, 24, 970–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priddy, R.D. Sustainability: The train has left the station. MRS Energy and Sustainability 2017, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjåfjell, B. Reforming EU Company Law to Secure the Future of European Business. The Palgrave Handbook of ESG and Corporate Governance 2022, 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlian, D.N.; Popa, A.F.; Nicoară, Ș.A.; Bâtcă-Dumitru, C.G. Examining the Causality between Integrated Reporting and Stock Market Capitalization. The Case of the European Renewable Energy Equipment and Services Industry. Energies 2023, 16, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principale, S.; Pizzi, S. The Determinants of TCFD Reporting: A Focus on the Italian Context. Administ Sci 2023, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khunkaew, R.; Wichianrak, J.; Suttipun, M. Sustainability reporting, gender diversity, firm value and corporate performance in ASEAN region. Cogent Bus Manag 2023, 10, 2200608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Isaksson, R. Sustainability reporting as a 21st century problem statement: using a quality lens to understand and analyse the challenges. TQM Journal 2023, 35, 1310–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, E.; Che-Ahmad, A.; Abdulmalik, S.O. Board governance mechanisms and sustainability reporting quality: A theoretical framework. Cogent Bus Manag 2020, 7, 1771075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, Z.; Seno, R.; Alodat, A.Y.M.; Hashim, H.A. Does the Audit Committee Effectiveness Influence the Reporting Practice of GHG Emissions In Malaysia? J Sustainability Sci Manag 2022, 17, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ararat, M.; Sayedy, B. Gender and climate change disclosure: An interdimensional policy approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, D.P.; Oza, S. Gender representation in ESG communication of Indian companies: Observations and insights. Infrastructure development - theory, practice and policy: Sustainability and resilience: 2021 conference compendium (pp. 16-21) 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pallissery, F.; Beerannavar, C.R.; Thomas, F. Women on the Board of Indian It Companies: Are They Audible and Visible?. In: Naser, M.A. (eds) New Approaches to CSR, Sustainability and Accountability, Volume IV 2023. Accounting, Finance, Sustainability, Governance & Fraud: Theory and Application. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Giron, A.; Kazemikhasragh, A.; Cicchiello, A.F.; Panetti, E. Company characteristics and sustainability reporting: Evidence from Asia and Africa. Int J Social Ecol Sust Dev 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girón, A.; Kazemikhasragh, A.; Cicchiello, A.F; Panetti, E. Sustainability reporting and firms’ economic performance: Evidence from Asia and Africa. J Know Econ 2021, 12, 1741–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Hussainey, K.; Aly, D. Determinants of sustainability reporting decision: Evidence from Pakistan. J Sust Fin Inv 2022, 12, 214–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emma, G.; Jennifer, M. Is SDG reporting substantial or symbolic? an examination of controversial and environmentally sensitive industries. J Cleaner Prod 2021, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchiello, A.F.; Fellegara, A.M.; Kazemikhasragh, A.; Monferrà, S. Gender diversity on corporate boards: How Asian and African women contribute on sustainability reporting activity. Gender Manag 2021, 36, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassreddine, G. Structural analysis of factors influencing environmental disclosure. Cogent Econ Fin 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningrum, I.F.S.; Oktavilia, S.; Utami, S. The effect of company characteristics and gender diversity on disclosures related to sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Orzes, G.; Jia, F.; Chen, L. Does GRI sustainability reporting pay off? An empirical investigation of publicly listed firms in China. Bus Soc 2021, 60, 1738–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bananuka, J.; Nkundabanyanga, S.K.; Kaawaase, T.K.; Mindra, R.K.; Kayongo, I.N. Sustainability performance disclosures: The impact of gender diversity and intellectual capital on GRI standards compliance in Uganda. J Account Emerg Econ 2022, 12, 840–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrian, T.; Sulaeman, P.; Yuliana; Agata, Y. D. Sustainable development goal disclosures in Indonesia: Challenges and opportunities. Rev Intl Geog Educ Online 2021, 11, 604–617. [Google Scholar]

- De Moraes, E.A.; Ribeiro, F.G.; De Carvalho, E.; Da Silva, A.M.M. Disclosure of Social Information and Women on the Board of Directors. Rev Ges Social Amb 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivic, A.; Saviolidis, N.M.; Johannsdottir, L. Drivers of sustainability practices and contributions to sustainable development evident in sustainability reports of European mining companies. Discover Sustainability 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova Román, C.; Zorio-Grima, A.; Merello, P. Economic development and CSR assurance: Important drivers for carbon reporting… yet inefficient drivers for carbon management? Techn Forec Social Change 2021, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahyani, F.E. Corporate board diversity and carbon disclosure: evidence from France. Account Res J 2022, 35, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, N. , Vij, A. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firms: Empirical evidence from UAE. Int J Sust Eng 2021, 14, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, E.; Mansi, M.; Pandey, R. Diversity in totality: A study of diversity disclosures by new zealand stock exchange listed companies. Int J Human Res Manag 2021, 32, 1419–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oware, K.M.; Mallikarjunappa, T. Financial performance and gender diversity. the effect of family management after a decade attempt. Soc Bus Rev 2021, 16, 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lesnikov, P.; Kunz, N.C.; Harris, L.M. Gender and sustainability reporting – critical analysis of gender approaches in mining. Resourc Policy 2023, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G. Real Estate Insights The increasing importance of the “S” dimension in ESG. J Prop Inv Fin 2023, 41, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Complete reference | # citations |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Elkins, H., Entwistle, G. (2023). A Canadian Response to the Pursuit of Global Sustainability Reporting Standards*. Accounting Perspectives, 22 (1), pp. 7-54. DOI: 10.1111/1911-3838.12297 | 0 |

| 2023 | Khunkaew, R., Wichianrak, J., Suttipun, M. (2023). Sustainability reporting, gender diversity, firm value and corporate performance in ASEAN region. Cogent Business and Management, 10 (1), art. no. 2200608. DOI: 10.1080/23311975.2023.2200608 | 0 |

| 2023 | Kordecki, G.S., Grant, D.M. (2023). Sustainability Gains through Enhanced Reporting Requirements. International Journal of Business, 28 (3), pp. 1-26. DOI: 10.55802/IJB.028(3).001 | 0 |

| 2023 | Ng, A.W., Leung, T.C.H., Yu, T.-W., Cho, C.H., Wut, T.M. (2023). Disparities in ESG reporting by emerging Chinese enterprises: evidence from a global financial center. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal. DOI: 10.1108/SAMPJ-08-2021-0323 | 0 |

| 2023 | Nyantakyi, G., Atta Sarpong, F., Adu Sarfo, P., Uchenwoke Ogochukwu, N., Coleman, W. (2023). A boost for performance or a sense of corporate social responsibility? A bibliometric analysis on sustainability reporting and firm performance research (2000-2022). Cogent Business and Management, 10 (2), art. no. 2220513. DOI: 10.1080/23311975.2023.2220513 | 2 |

| 2023 | Principale, S., Pizzi, S. (2023). The Determinants of TCFD Reporting: A Focus on the Italian Context. Administrative Sciences, 13 (2), art. no. 61. DOI: 10.3390/admsci13020061 | 0 |

| 2023 | Ramanathan, S., Isaksson, R. (2023). Sustainability reporting as a 21st century problem statement: using a quality lens to understand and analyse the challenges. TQM Journal, 35 (5), pp. 1310-1328. DOI: 10.1108/TQM-01-2022-0035 | 2 |

| 2023 | Sahlian DN, Popa AF, Nicoară ȘA, Bâtcă-Dumitru CG. (2023). Examining the Causality between Integrated Reporting and Stock Market Capitalization. The Case of the European Renewable Energy Equipment and Services Industry. Energies. 2023; 16(3):1398. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031398. | 0 |

| 2023 | Vitolla, F., Raimo, N., Campobasso, F., Giakoumelou, A. (2023). Risk disclosure in sustainability reports: Empirical evidence from the energy sector. Utilities Policy, 82, art. no. 101587. DOI: 10.1016/j.jup.2023.101587 | 0 |

| 2023 | Zaid, M. A. A. (2023). Accounting for Climate Change in Light of the IFRS Foundation Movements: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 621 LNNS, pp. 389-403. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-26956-1_38 | 0 |

| 2022 | Andersson, F.N.G., Arvidsson, S. (2022). Understanding, mapping and reporting of climate-related risks among listed firms in Sweden. Climate Policy. DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2116383 | 3 |

| 2022 | Jizi, M., Nehme, R., Melhem, C. (2022). Board gender diversity and firms' social engagement in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 41 (2), pp. 186-206. DOI: 10.1108/EDI-02-2021-0041 | 8 |

| 2022 | Salleh, Z., Seno, R., Alodat, A.Y.M., Hashim, H.A. (2022). Does the Audit Committee Effectiveness Influence the Reporting Practice of GHG Emissions In Malaysia? Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 17 (1), pp. 204-220. DOI: 10.46754/jssm.2022.01.014 | 6 |

| 2022 | Sjåfjell, B. (2022). Reforming EU Company Law to Secure the Future of European Business. The Palgrave Handbook of ESG and Corporate Governance, pp. 59-85. | 0 |

| 2021 | Dye, J., McKinnon, M., Van der Byl, C. (2021). Green Gaps: Firm ESG Disclosure and Financial Institutions’ Reporting Requirements. Journal of Sustainability Research, 3 (1), art. no. e210006. DOI: 10.20900/jsr20210006 | 8 |

| 2021 | Sepúlveda-Alzate, Y.M., García-Benau, M.A., Gómez-Villegas, M. (2021). Materiality assessment: the case of Latin American listed companies. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 13 (1), pp. 88-113. DOI: 10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2020-0358 | 9 |

| 2020 | Jang, N. (2020). The value of voluntary sustainability reporting. Bracing for Climate Change: Strategies for Mitigation and Resiliency Planning Conference Proceedings. | 0 |

| 2020 | Karaman, A.S., Kilic, M., Uyar, A. (2020). Green logistics performance and sustainability reporting practices of the logistics sector: The moderating effect of corporate governance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, art. no. 120718. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120718 | 70 |

| 2020 | Macoskey, K.A. (2020). A survey of U.S. Industrial sustainability reports - Part 2. Proceedings of the Air and Waste Management Association's Annual Conference and Exhibition, AWMA, 2020-June. | 0 |

| 2020 | Melles, G. (2020). Sustainability Reporting in Australian Universities: Case Study of Campus Sustainability Employing Institutional Analysis. World Sustainability Series, pp. 945-974. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-26759-9_56 | 6 |

| 2020 | Moses, E., Che-Ahmad, A., Abdulmalik, S.O. (2020). Board governance mechanisms and sustainability reporting quality: A theoretical framework. Cogent Business and Management, 7 (1), art. no. 1771075. DOI: 10.1080/23311975.2020.1771075 | 15 |

| 2019 | Antoncic, M. (2019). Why sustainability? Because risk evolves and risk management should too. Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions, 12 (3), pp. 206-216. | 9 |

| 2019 | Ararat, M., Sayedy, B. (2019). Gender and climate change disclosure: An interdimensional policy approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11 (24), art. no. 7217. DOI: 10.3390/su11247217 | 11 |

| 2019 | Petera P., Wagner J., Paksiova R., Krehnacova A. (2019). Sustainability information in annual reports of companies domiciled in the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic. Engineering Economics, 30 (4), pp. 483 - 495. DOI: 10.5755/j01.ee.30.4.22481. | 16 |

| 2019 | Roschnik, S., Lomax, R., Tennison, I. (2019). The transformation to environmentally sustainable health systems: The national health service example in England. Lakartidningen, 116 (9-10), art. no. 412. | 0 |

| 2018 | Cooper, L., Gorman, D. (2018). A Holistic Approach to Embedding Social Responsibility and Sustainability in a University—Fostering Collaboration Between Researchers, Students and Operations. World Sustainability Series, pp. 177-192. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-63007-6_11 | 4 |

| 2018 | Omran, A., Schwarz-Herion, O. (2018). The impact of climate change on our life: The questions of sustainability. The Impact of Climate Change on Our Life: The Questions of Sustainability, pp. 1-250. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-10-7748-7. ISBN: 978-981-10-7747-0 | 6 |

| 2018 | Wu, S.R., Shao, C., Chen, J. (2018). Approaches on the screening methods for materiality in sustainability reporting. Sustainability (Switzerland), 10 (9), art. no. 3233. DOI: 10.3390/su10093233 | 20 |

| 2017 | Facchini, A., Scala, A., Lattanzi, N., Caldarelli, G., Liberatore, G., Dal Maso, L., Di Nardo, A. (2017). Complexity science for sustainable smart water grids. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 708, pp. 26-41. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-57711-1_3 | 3 |

| 2017 | Priddy, R.D. (2017). Sustainability: The train has left the station. MRS Energy and Sustainability, 4 (1), art. no. 3. DOI: 10.1557/mre.2017.4 | 8 |

| 2015 | Murphy, H., Janus, B. (2015). Managing HSE performance through sustainability reporting. Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE E and P Health, Safety, Security and Environmental Conference - Americas 2015, pp. 284-292. | 1 |

| 2015 | Thistlethwaite, J. (2015). The politics of experimentation in climate change risk reporting: the emergence of the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB). Environmental Politics, 24 (6), pp. 970-990. DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2015.1051325 | 12 |

| 2015 | Trotman, A.J., Trotman, K.T. (2015). Internal audit’s role in GHG emissions and energy reporting: Evidence from audit committees, senior accountants, and internal auditors. Auditing, 34 (1), pp. 199-230. DOI: 10.2308/ajpt-50675 | 69 |

| 2014 | Ashley, P. (2014). A sustainability index for manufactured products? A conceptual paper. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 21 (1), pp. 5-10. DOI: 10.1080/14486563.2013.848175 | 2 |

| 2014 | Lindsey, C.O., Janus, B., Murphy, H. (2014). Growing expectations: The rising tide of sustainability reporting initiatives and their challenges for the oil and gas industry. Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE International Conference on Health, Safety and Environment 2014: The Journey Continues, 1, pp. 36-42. | 1 |

| 2011 | Lozano, R., Huisingh, D. (2011). Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19 (2-3), pp. 99-107. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.004 | 370 |

| 2010 | Curlee, C., Retzsch, W., Robinson, N., Edwards, G., Hunter, D., Krishna, P., Granquist, M., Gimelli, N., Nordang, H., Chauvin, D., Buckley, H., Romer, R. (2010). The oil & gas industry guidance on voluntary sustainability reporting: A major revision on the horizon (publication due mid-2010). Society of Petroleum Engineers - SPE International Conference on Health, Safety and Environment in Oil and Gas Exploration and Production 2010, 2, pp. 1410-1416. | 0 |

| 2007 | Chakraborty, A.B. (2007). Carbon management - The emerging paradigm for the oil industry. Proceedings - SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, 4, pp. 2410-2415. | 0 |

| 2005 | Hilton, P.A. (2005). Carbon/Greenhouse Gas Transparency and Socially Responsible Investing. Green Trading Markets, pp. 15-23. DOI: 10.1016/B978-008044695-0/50005-7 | 0 |

| Total | 661 |

| Subject area - search criteria 1 | documents | Subject area - search criteria 2 | documents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 6 | Business, Management and Accounting | 8 |

| Engineering | 6 | Environmental Science | 6 |

| Environmental Science | 5 | Social Sciences | 5 |

| Business, Management and Accounting | 4 | Decision Sciences | 4 |

| Social Sciences | 3 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance | 3 |

| Earth and Planetary Sciences | 2 | Energy | 3 |

| Materials Science | 1 | Computer Science | 1 |

| Economics, Econometrics and Finance | 1 | Earth and Planetary Sciences | 1 |

| Agricultural and Biological Sciences | 1 | Engineering | 1 |

| Computer Science | 1 | Mathematics | 1 |

| Chemical Engineering | 1 | ||

| Mathematics | 1 | ||

| Health Professions | 1 | ||

| Decision Sciences | 1 | ||

| Subject area - search criteria 3 | documents | Subject area - search criteria 4 | documents |

| Energy | 7 | Energy | 4 |

| Business, Management and Accounting | 6 | Business, Management and Accounting | 3 |

| Environmental Science | 4 | Environmental Science | 3 |

| Social Sciences | 3 | Social Sciences | 2 |

| Decision Sciences | 2 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance | 1 |

| Economics, Econometrics and Finance | 2 | Engineering | 1 |

| Engineering | 2 | Health Professions | 1 |

| Mathematics | 1 | ||

| Medicine | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).