Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample Demographics

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Gender Differences

3.2. Correlational Analyses

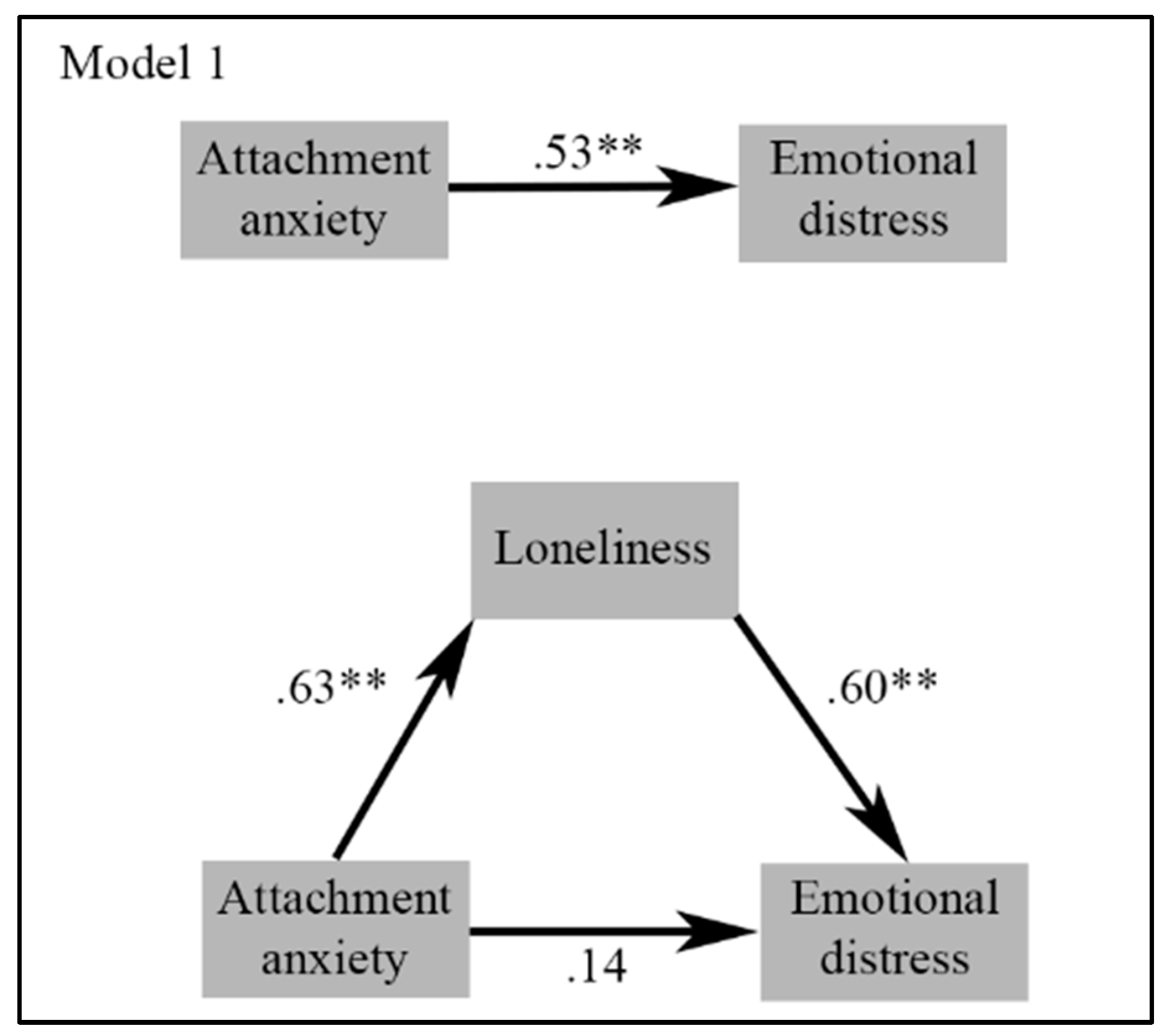

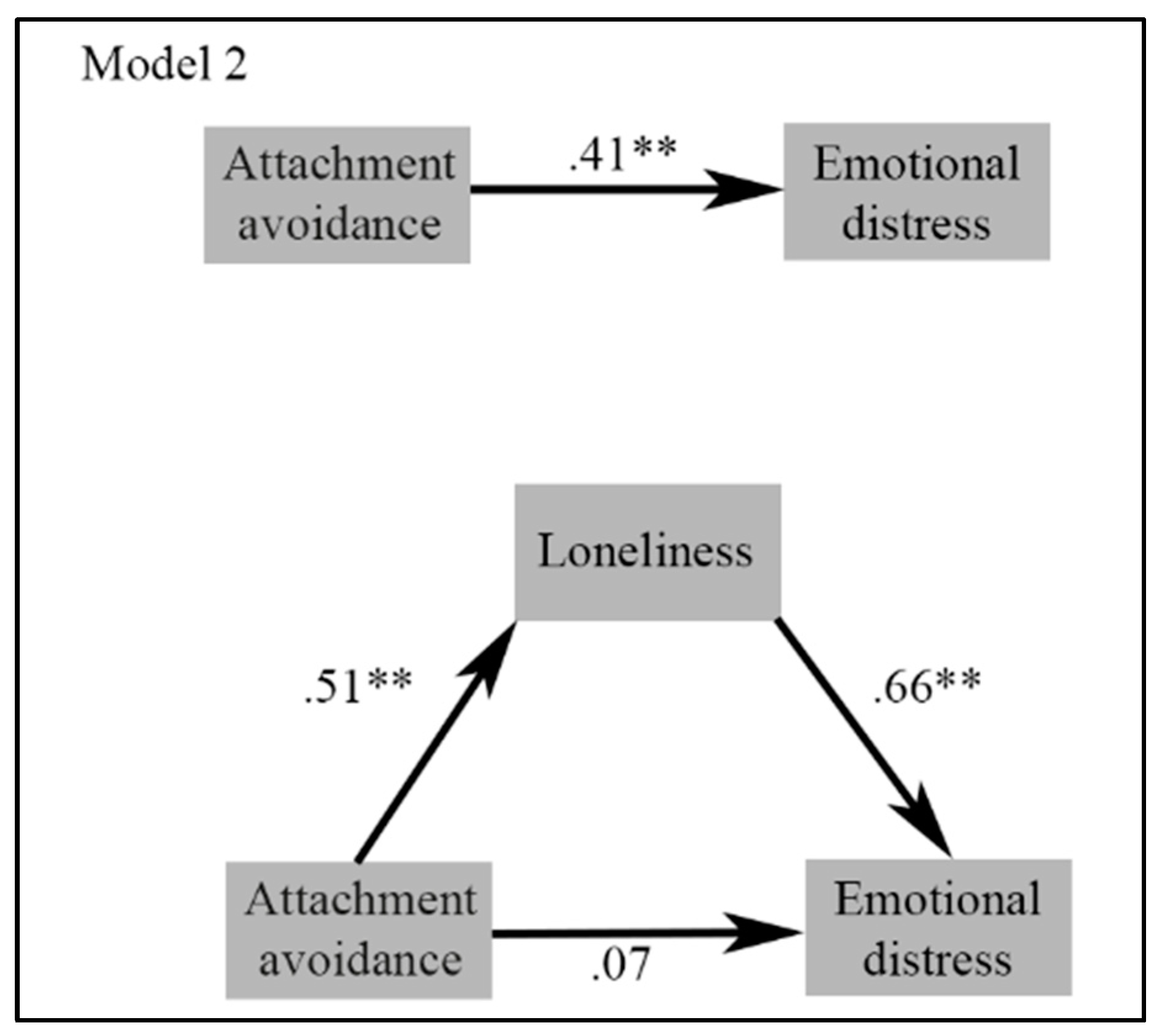

3.3. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, L.; Bouey, J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerging infectious diseases. 2020, 26, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dascalu, S.; Geambasu, O.; Raiu, C.V.; Azoicai, D.; Popovici, E.D.; Apetrei, C. COVID-19 in Romania: What Went Wrong? Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9, 813941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, N. Covid: Romania’s health system torn apart by pandemic.BBC. 23 October 2021. 23 October. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-58992090.

- Campion, J.; Javed, A.; Sartorius, N.; Marmot, M. Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 657–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, W.; Gulati, G.; Kelly, B.D. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 2020, 113, 311–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiovanni, C.; Conley, J.; Chiu, D.; Zaborski, J. Factors Influencing Compliance with Quarantine in Toronto During the 2003 SARS Outbreak. Biosecurity Bioterrorism Biodefense Strategy Pract. Sci. 2004, 2, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.T.; Chau, P.H.; Yip, P.S. A revisit on older adults suicides and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied sciences. 2008, 23, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. The psychology of pandemics. Annual review of clinical psychology 2022, 18, 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Nguyen, T.-V.T.; Zhong, J.; Liu, J. A COVID-19 descriptive study of life after lockdown in Wuhan, China. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.; Niederer, D.; Werner, A.M.; Czaja, S.J.; Mikton, C.; Ong, A.D.; Rosen, T.; Brähler, E.; Beutel, M.E. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 2022, 77, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Heal. 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, D.; Peplau, L.A. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal relationships 1981, 3, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E.; Braun, B. Loneliness and social isolation-a private problem, a public issue. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences. 2019, 111, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D.V.; Lee, E.E.; Cacioppo, S. Battling the modern behavioral epidemic of loneliness: suggestions for research and interventions. JAMA psychiatry 2020, 77, 553–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foti, S.A.; Khambaty, T.; Birnbaum-Weitzman, O.; Arguelles, W.; Penedo, F.; Giacinto, R.A.E.; Gutierrez, A.P.; Gallo, L.C.; Giachello, A.L.; Schneiderman, N.; et al. Loneliness, Cardiovascular Disease, and Diabetes Prevalence in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Heal. 2020, 22, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellaoui, A.; Sanchez-Roige, S.; Sealock, J.; Treur, J.L.; Dennis, J.; Fontanillas, P.; Elson, S. 23andme Research Team, Nivard MG, Ip HF, van der Zee M. Phenome-wide investigation of health outcomes associated with genetic predisposition to loneliness. Human molecular genetics. 2019, 28, 3853–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.S.; Boyle, A.; Wilson, R.S.; James, B.D.; Leurgans, S.E.; Arnold, S.E.; Bennett, D.A. Loneliness and the rate of motor decline in old age: the rush memory and aging project, a community-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Victor, C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 1368–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baarck, J.; D’Hombres, B.; Tintori, G. Loneliness in Europe before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heal. Policy 2022, 126, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Heal. 2020, 186, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.S.; Bowlby, J. An ethological approach to personality development. American psychologist. 1991, 46, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, C. Conceptualizing romantic love as an attachment process. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1987, 52, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larose, S.; Guay, F.; Boivin, M. Attachment, Social Support, and Loneliness in Young Adulthood: A Test of Two Models. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinckrodt, B. Attachment, Social Competencies, Social Support, and Interpersonal Process in Psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 2000, 10, 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, M.E.; Hamarta, E.; Ari, R. An Investigation of Social Skills and Loneliness Levels of University Students with Respect to Their Attachment Styles in a Sample of Turkish Students. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2005, 33, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.; Cutrona, C.E.; Rose, J.; Yurko, K. Social and emotional loneliness: an examination of Weiss’s typology of loneliness. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1984, 46, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalit M, Margalit M. Loneliness Conceptualization. Lonely Children and Adolescents: Self-Perceptions, Social Exclusion, and Hope. 2010:1-28.

- Bernardon, S.; Babb, K.A.; Hakim-Larson, J.; Gragg, M. Loneliness, attachment, and the perception and use of social support in university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement. 2011, 43, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Beck, L.A. Attachment processes in adult romantic relationships. InAPA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 3: Interpersonal relations. 2015 (pp. 33-64). American Psychological Association. . [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss. Volume II. Separation, anxiety and anger. InAttachment and loss. volume II. Separation, anxiety and anger 1973 (pp. 429-p).

- Lewis, K.C.; Roche, M.J.; Brown, F.; Tillman, J.G. Attachment, loneliness, and social connection as prospective predictors of suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A relational diathesis-stress experience sampling study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2023, 53, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollè, L.; Trombetta, T.; Calabrese, C.; Vismara, L.; Sechi, C. Adult attachment, loneliness, COVID-19 risk perception and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Psychological stress and the coping process, 1984.

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1989, 56, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.L.; Armeli, S.; Tennen, H. Appraisal-Coping Goodness of Fit: A Daily Internet Study. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, Q.H.; Wei, K.C.; Vasoo, S.; Chua, H.C.; Sim, K. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population: Practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singap. Med J. 2020, 61, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Havewala, M.; Zhu, Q. COVID-19 stressful life events and mental health: Personality and coping styles as moderators. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurvich, C.; Thomas, N.; Thomas, E.H.; Hudaib, A.-R.; Sood, L.; Fabiatos, K.; Sutton, K.; Isaacs, A.; Arunogiri, S.; Sharp, G.; et al. Coping styles and mental health in response to societal changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbóczy, S.; Szemán-Nagy, A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Harsányi, S.; Ocsenás, D.; Rekenyi, V.; Al-Tammemi, A.A.; Kolozsvári, L.R. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC psychology. 2021, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuhan, G.C.; Nicolau, R.G.; Iliescu, D. Perceived stress and wellbeing in Romanian teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The intervening effects of job crafting and problem-focused coping. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, R.; Hwang, J.; Hong, W.; Wang, J. The Impact of Different Coping Styles on Psychological Distress during the COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluharty, M.; Bu, F.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. Coping strategies and mental health trajectories during the first 21 weeks of COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 279, 113958–113958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of medical Internet research. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, N.L. Revised Adult Attachment Scale. 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1989, 56, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.W.; Yau, J.K.; Chan, C.L.; Kwong, R.S.; Ho, S.M.; Lau, C.C.; Lau, F.L.; Lit, C.H. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2005, 12, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasovan, D.I.; Sava, F.A. Translation, adaptation, and validation on Romanian population of COPE questionnaire for coping mechanisms analysis. Cognition, Brain, Behavior. 2013, 17, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, C.N.; Bjorling, G.; Elfstrom, M.L.; Persson, H.; Saboonchi, F. Assessment of Coping Strategies and Their Associations With Health Related Quality of Life in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure: the Brief COPE Restructured. Cardiol. Res. 2015, 6, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications; 2017 Oct 30.

- Pieh, C.; O´ Rourke, T.; Budimir, S.; Probst, T. Relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. PloS ONE 2020, 15, e0238906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, A.; Ali, A.Z. Living under the shadow of a pandemic: The psychological challenges underlying social distancing and awareness raising. Psychol. Trauma: Theory, Res. Pr. Policy 2020, 12, 508–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. Social and behavioral consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Validation of a Pandemic Disengagement Syndrome Scale (PDSS) in four national contexts. Psychol. Assess. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauhanen, L.; Yunus, W.M.A.W.M.; Lempinen, L.; Peltonen, K.; Gyllenberg, D.; Mishina, K.; Gilbert, S.; Bastola, K.; Brown, J.S.L.; Sourander, A. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, L.; Yang, L.; Mezo, P.G.; Liu, R. Age disparities in mental health during the COVID19 pandemic: The roles of resilience and coping. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 305, 115031–115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Wetherall, K.; Cleare, S.; McClelland, H.; Melson, A.J.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; O’Carroll, R.E.; O’Connor, D.B.; Platt, S.; Scowcroft, E.; et al. Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 218, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okely, J.A.; Corley, J.; Welstead, M.; Taylor, A.M.; Page, D.; Skarabela, B.; Redmond, P.; Cox, S.R.; Russ, T.C. Change in Physical Activity, Sleep Quality, and Psychosocial Variables during COVID-19 Lockdown: Evidence from the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, P.R.; Mikulincer, M. An overview of adult attachment theory. Attachment theory and research in clinical work with adults. 2009, 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Turton, H.; Berry, K.; Danquah, A.; Green, J.; Pratt, D. An investigation of whether emotion regulation mediates the relationship between attachment insecurity and suicidal ideation and behaviour. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2022, 29, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davila, J.; Burge, D.; Hammen, C. Why does attachment style change? Journal of personality and social psychology. 1997, 73, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.A.; Simpson, J.A.; Berlin, L.J. Taking perspective on attachment theory and research: nine fundamental questions. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2022, 24, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Feußner, C.; Ahnert, L. Meta-analytic evidence for stability in attachments from infancy to early adulthood. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2013, 15, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. No reliable gender differences in attachment across the lifespan. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2009, 32, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Goldzweig, G.; Sela-Oren, T.; Pizem, N.; Bar-Sela, G.; Wolf, I. Attachment style, social support and finding meaning among spouses of colorectal cancer patients: Gender differences. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.E.; Hettich, N.; Ernst, M.; Schmutzer, G.; Tibubos, A.N.; Braehler, E. Mental health and loneliness in the German general population during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to a representative pre-pandemic assessment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.S.; Crivelli, L.; Guimet, N.M.; Allegri, R.F.; Pedreira, M.E. Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: Latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, P.R.; Mikulincer, M.; Sahdra, B.; Gross, J. Attachment security as a foundation for kindness toward self and others. The Oxford handbook of hypo-egoic phenomena. 2016 Oct 5;10. [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.I.; Pietromonaco, P.R.; Gunlicks, M.; Sayer, A. Dating couples’ attachment styles and patterns of cortisol reactivity and recovery in response to a relationship conflict. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, L.M.; Fagundes, C.P. Psychobiological research on attachment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010, 27, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Berntson, G.G.; Adolphs, R.; Carter, C.S.; Davidson, R.J.; McClintock, M.; McEwen, B.S.; Meaney, M.; Schacter, D.L.; Sternberg, E.M.; et al. Neuroendocrine Perspectives on Social Attachment and Love. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998, 23, 779–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; A Beck, L. Adult attachment and physical health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 25, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. The Attachment Behavioral System In Adulthood: Activation, Psychodynamics, and Interpersonal Processes. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 35, pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, F.G.; Brennan, K.A. Dynamic processes underlying adult attachment organization: Toward an attachment theoretical perspective on the healthy and effective self. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000, 47, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Berry, K.; Danquah, A.; Pratt, D. The role of psychological and social factors in the relationship between attachment and suicide: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2020, 27, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Gvion, Y.; Horesh, N.; Apter, A. Attachment Patterns in Medically Serious Suicide Attempts: The Mediating Role of Self-Disclosure and Loneliness. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2013, 43, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Marshall, T. Anxious Attachment and Relationship Processes: An Interactionist Perspective. J. Pers. 2011, 79, 1219–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Dell’Osso, B.; Dell’Osso, M.C.; Consoli, G.; Del Debbio, A.; Mungai, F.; Vivarelli, L.; Albanese, F.; Piccinni, A.; Rucci, P.; et al. Romantic Attachment in Patients with Mood and Anxiety Disorders. CNS Spectrums 2007, 12, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, W.; Heimberg, R.G.; Hart, T.A.; Schneier, F.R.; Liebowitz, M.R. Attachment in individuals with social anxiety disorder: the relationship among adult attachment styles, social anxiety, and depression. Emotion. 2001, 1, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodhouse, S.; Ayers, S.; Field, A.P. The relationship between adult attachment style and post-traumatic stress symptoms: A meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 35, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostacoli, L.; Cosma, S.; Bevilacqua, F.; Berchialla, P.; Bovetti, M.; Carosso, A.R.; Malandrone, F.; Carletto, S.; Benedetto, C. Psychosocial factors associated with postpartum psychological distress during the Covid-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfa, N.; Harper, M.; Nicolais, G.; Bhui, K. Adult attachment style as a risk factor for maternal postnatal depression: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2014, 2, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P.R.; Schachner, D.A.; Mikulincer, M. Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005, 31, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vowels, L.M.; Carnelley, K.B. Attachment styles, negotiation of goal conflict, and perceived partner support during COVID-19. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 171, 110505–110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunebaum, M.F.; Galfalvy, H.C.; Mortenson, L.Y.; Burke, A.K.; Oquendo, M.A.; Mann, J.J. Attachment and social adjustment: Relationships to suicide attempt and major depressive episode in a prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 123, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1991, 61, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M.; Solomon, J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention 1990, 1, 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- Briere, J.; Runtz, M.; Eadie, E.M.; Bigras, N.; Godbout, N. The Disorganized Response Scale: Construct validity of a potential self-report measure of disorganized attachment. Psychol. Trauma: Theory, Res. Pr. Policy 2019, 11, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paetzold, R.L.; Rholes, W.S.; Kohn, J.L. Disorganized Attachment in Adulthood: Theory, Measurement, and Implications for Romantic Relationships. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2015, 19, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeney, J.E.; Wright, A.G.; Stepp, S.D.; Hallquist, M.N.; Lazarus, S.A.; Beeney, J.R.; Scott, L.N.; Pilkonis, P.A. Disorganized attachment and personality functioning in adults: A latent class analysis. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2017, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, M.; Provost, M.A. Resilience in Adolescents: Protective Role of Social Support, Coping Strategies, Self-Esteem, and Social Activities on Experience of Stress and Depression. J. Youth Adolesc. 1999, 28, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Coping and emotion. Stress and coping: An anthology 1991 Dec 31 (pp. 207-227). Columbia University Press.

- Rettie, H.; Daniels, J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edjolo, A.; Dorey, J.-M.; Herrmann, M.; Perrot, C.; Lebrun-Givois, C.; Buisson, A.; El Haouari, H.; Laurent, B.; Pongan, E.; Rouch, I. Stress, Personality, Attachment, and Coping Strategies During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The STERACOVID Prospective Cohort Study Protocol. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 918428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Male (N=30) |

Female (N=111) |

t-test |

|||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p | |

| Age | 35.22 | 10.80 | 35.03 | 10.23 | .00 |

| Loneliness | 21 | 13.69 | 22.81 | 13.32 | .513 |

| Emotional distres | 17.9 | 13.40 | 17.89 | 12.86 | .998 |

| Attachment anxiety | 13.43 | 5.32 | 14.18 | 6.59 | .568 |

| Attachment avoidance | 33.56 | 7.36 | 33.06 | 8.74 | .773 |

| Problem-focused | 8.06 | 4.05 | 10.23 | 4.35 | .015 |

| Emotion-focused | 33.33 | 14.94 | 41.08 | 14.31 | .001 |

| Avoidant | 22.50 | 9.21 | 27.37 | 10.61 | .023 |

| Socially supported | 15.50 | 7.47 | 19.43 | 9.94 | .046 |

| N=141 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1. Age | - | ||||||||

| 2. Loneliness | -.13 | - | |||||||

| 3. Emotional distress | -.20* | .70*** | - | ||||||

| 4. Attachment anxiety | -.19* | .63*** | .53*** | - | |||||

| 5. Attachment avoidance | -.15 | .51*** | .41*** | .61*** | - | ||||

| 6. Problem-focused coping | -.17* | .21* | .24** | .05 | .11 | - | |||

| 7. Avoidant coping | -.22** | .10 | .22 | .16 | -.03 | .47*** | - | ||

| 8. Emotion-focused coping | -17* | .08 | .13 | .17 | .00 | .73*** | .71*** | - | |

| 9. Socially supported coping | -.00 | .20* | .26** | -.02 | .09 | .42*** | .69*** | .62*** | - |

| * represents p < .05 ** represents p < .01 *** represents p<.001 |

|

Loneliness R.sq = .42, p<.001 |

Emotional distress R.sq = .30, p<.001 |

|||||

| β | T | p | β | T | p | |

| Attachment anxiety | .50 | 6.13 | .000 | .42 | 4.72 | .000 |

| Attachment avoidance | .20 | 2.46 | .015 | .14 | 1.59 | .113 |

| Age | -.005 | -.08 | .935 | -.10 | -1.41 | .160 |

|

Loneliness R.sq .11, p<.01 |

Emotional distress R.sq = .18, p<.001 |

|||||

| β | T | p | β | T | p | |

| Problem-focused | .33 | 2.79 | .006 | .30 | 2.67 | .008 |

| Emotion-focused | -.38 | -2.47 | .015 | -.25 | -1.73 | .083 |

| Avoidant | .01 | .12 | .903 | -.23 | -1.82 | .070 |

| Socially supported | .28 | 2.38 | .019 | .45 | 3.93 | .000 |

| Age | -.13 | -1.57 | .117 | -.24 | -3.01 | .003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).