Submitted:

04 August 2023

Posted:

07 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

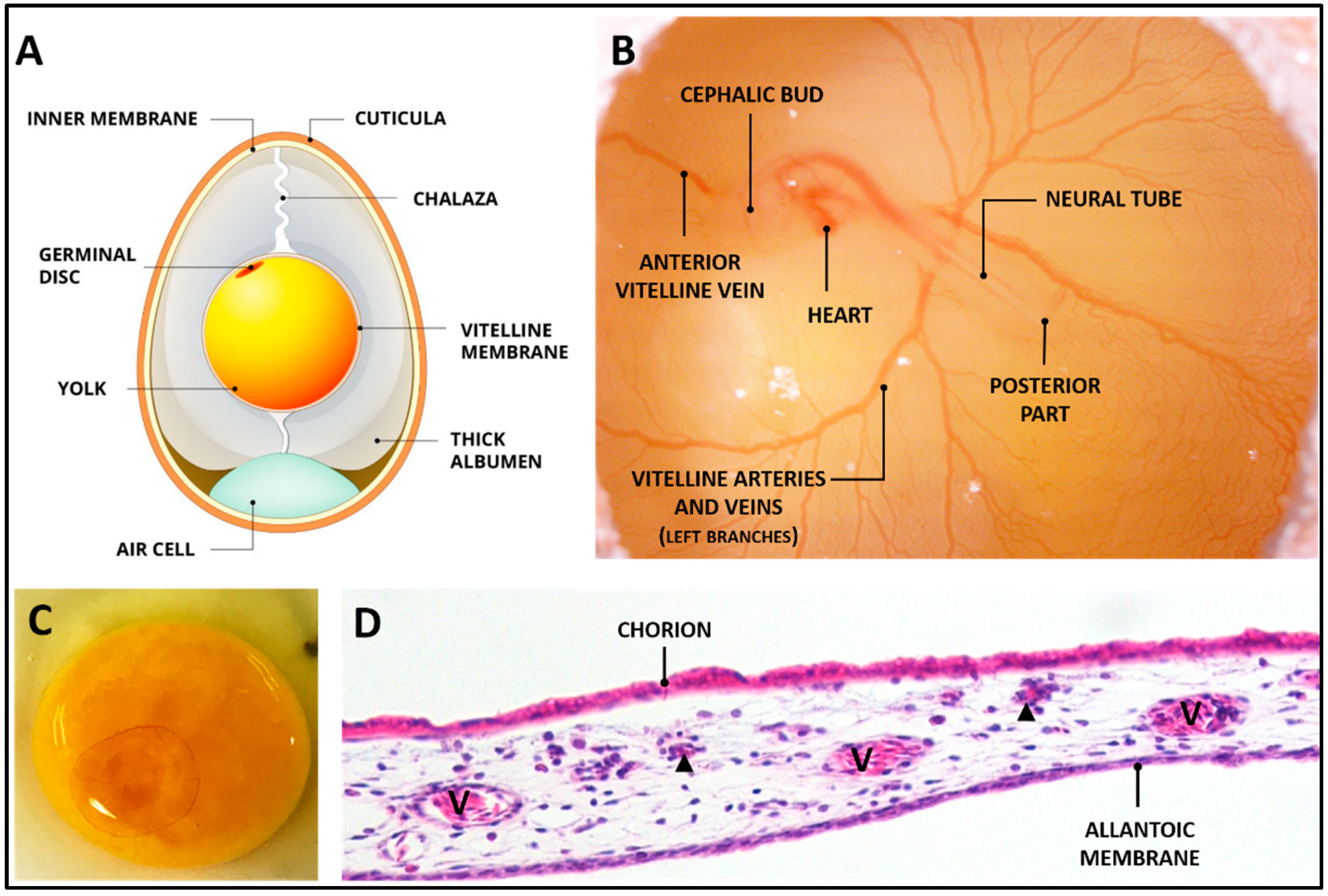

2. The CAM

3. The Application of CAM Up to Now

3.1. Use of the Cam Assay for Cancer Studies

3.2. Cancer Hallmarks Studied in CAM: Angiogenesis

3.3. Cancer Hallmarks Studied in CAM: Metastatic Potential

3.4. Tumor Therapy Test in CAM

4. Use of the CAM Assay to Validate Scaffold for Regenerative Purposes

5. Use of CAM to Set-Up Organotypic Culture

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique; Methuen, Ed.; London, 1959.

- Hippenstiel, S.; Thöne-Reineke, C.; Kurreck, J. Animal Experiments: EU Is Pushing to Find Substitutes Fast. Nature 2021, 600, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fentem, J.; Malcomber, I.; Maxwell, G.; Westmoreland, C. Upholding the EU’s Commitment to ‘Animal Testing as a Last Resort’’ Under REACH Requires a Paradigm Shift in How We Assess Chemical Safety to Close the Gap Between Regulatory Testing and Modern Safety Science. ATLA Alternatives to Laboratory Animals 2021, 49, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.H.; Smith, L.; Owens, D.; Quelch, R.; Przyborski, S. Recreating Tissue Structures Representative of Teratomas In Vitro Using a Combination of 3D Cell Culture Technology and Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, P.; Gauvin, S.; Ferland, K.; Caneparo, C.; Pellerin, È.; Chabaud, S.; Bolduc, S. Bioengineering Innovative Human Three-Dimensional Tissue-Engineered Models as an Alternative to Animal Testing. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.J.; Mobbs, C.L.; González-Hau, A.L.; Freer, M.; Przyborski, S. Bioengineering Novel in Vitro Co-Culture Models That Represent the Human Intestinal Mucosa With Improved Caco-2 Structure and Barrier Function. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, E.; Murray, B.; Carnachan, R.; Przyborski, S. Alvetex®: Polystyrene Scaffold Technology for Routine Three Dimensional Cell Culture. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc., 2011; Vol. 695, pp. 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Golinelli, G.; Talami, R.; Frabetti, S.; Candini, O.; Grisendi, G.; Spano, C.; Chiavelli, C.; Arnaud, G.F.; Mari, G.; Dominici, M. A 3D Platform to Investigate Dynamic Cell-to-Cell Interactions Between Tumor Cells and Mesenchymal Progenitors. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagelli, A.; Candini, O.; Frabetti, S.; Dominici, M.; Giardino, L.; Calzà, L.; Baldassarro, V.A. A Novel Three-Dimensional Culture Device Favors a Myelinating Morphology of Neural Stem Cell-Derived Oligodendrocytes. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin-Shamsabadi, A.; Selvaganapathy, P.R. Tissue-in-a-Tube: Three-Dimensional in Vitro Tissue Constructs with Integrated Multimodal Environmental Stimulation. Mater Today Bio 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, C.; Paul, M.K. Organoid-Based 3D in Vitro Microphysiological Systems as Alternatives to Animal Experimentation for Preclinical and Clinical Research. Arch Toxicol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschhof, J.; Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Clevers, H. Organoids and Organs-on-Chips: Insights into Human Gut-Microbe Interactions. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.A.; Mummery, C.; Berridge, B.R.; Austin, C.P.; Tagle, D.A. Organs-on-Chips: Into the next Decade. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Su, W.; Guo, Y.; Deng, P.; Qin, J. Engineering Human Islet Organoids from IPSCs Using an Organ-on-Chip Platform. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manafi, N.; Shokri, F.; Achberger, K.; Hirayama, M.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Noorizadeh, F.; Hong, J.; Liebau, S.; Tsuji, T.; Quinn, P.M.J.; et al. Organoids and Organ Chips in Ophthalmology. Ocular Surface 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. Two New Applications in the Study of Angiogenesis the CAM Assay: Acellular Scaffolds and Organoids. Microvasc Res 2022, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, J.; Van Ongeval, C.; Ni, Y.; Li, Y. Cells Utilisation of Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Model Platform for Imaging-Navigated Biomedical Research. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.B.; da Silva, M.V.; de Morais Ribeiro, L.N. The Chicken Embryo as an in Vivo Experimental Model for Drug Testing: Advantages and Limitations. Lab Anim (NY) 2021, 50, 138–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadhich, P.; Das, B.; Pal, P.; Srivas, P.K.; Dutta, J.; Ray, S.; Dhara, S. A Simple Approach for an Eggshell-Based 3D-Printed Osteoinductive Multiphasic Calcium Phosphate Scaffold. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8, 11910–11924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, F.; Rimmer, N.; Pieles, U.; Buschmann, J.; Beaufils-Hugot, M. Characterization and in Ovo Vascularization of a 3D-Printed Hydroxyapatite Scaffold with Different Extracellular Matrix Coatings under Perfusion Culture. Biol Open 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiguera, S.; Macchiarini, P.; Ribatti, D. Chorioallantoic Membrane for in Vivo Investigation of Tissue-Engineered Construct Biocompatibility. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2012, 100 B, 1425–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, H.C.; Shekhar, A.; Rane, A.A.; Butcher, J.T. An Ex-Ovo Chicken Embryo Culture System Suitable for Imaging and Microsurgery Applications. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, I.; Kanczler, J.M.; Hulsart-Billstrom, G.; Inglis, S.; Oreffo, R.O.C. The Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay for Biomaterial Testing in Tissue Engineering: A Short-Term in Vivo Preclinical Model. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2017, 23, 938–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Vacca, A.; Roncali, L.; Burri, P.H.; Djonov, V. Chorioallantoic Membrane Capillary Bed: A Useful Target for Studying Angiogenesis and Anti-Angiogenesis in Vivo. Anatomical Record 2001, 264, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isachenko, V.; Mallmann, P.; Petrunkina, A.M.; Rahimi, G.; Nawroth, F.; Hancke, K.; Felberbaum, R.; Genze, F.; Damjanoski, I.; Isachenko, E. Comparison of in Vitro- and Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM)-Culture Systems for Cryopreserved Medulla-Contained Human Ovarian Tissue. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Jiménez, I.; Lanham, S.A.; Kanczler, J.M.; Hulsart-Billstrom, G.; Evans, N.D.; Oreffo, R.O.C. Remodelling of Human Bone on the Chorioallantoic Membrane of the Chicken Egg: De Novo Bone Formation and Resorption. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2018, 12, 1877–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazely, F.; Moses, D.C.; Ledinko, N. Effects of Retinoids on Invasion of Organ Cultures of Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane by Adenovirus Transformed Cells. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology 1985, 21, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Madrid, B.; Donnez, J.; Van Eyck, A.S.; Veiga-Lopez, A.; Dolmans, M.M.; Van Langendonckt, A. Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Model: A Useful Tool to Study Short-Term Transplantation of Cryopreserved Human Ovarian Tissue. Fertil Steril 2009, 91, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leene, W.; Duyzings, M.J.M.; Van Steeg, C. Lymphoid Stem Cell Identification in the Developing Thymus and Bursa of Fabricius of the Chick. Z. Zellforsch 1973, 136, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane in the Study of Angiogenesis and Metastasis; Springer, Ed.; 2010; ISBN 978-90-481-3843-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic, B.D.; Isakovic, K.; Lukic, M.L.; Vujanovic, N.L.; Petrovic, S.; Markovic, B.M. Immunological Capacity of the Chicken Embryo. I. Relationship between the Maturation of Lymphoid Tissues and the Occurrence of Cell-Mediated Immunity in the Developing Chicken Embryo. Immunology 1975, 29, 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Genova, T.; Petrillo, S.; Zicola, E.; Roato, I.; Ferracini, R.; Tolosano, E.; Altruda, F.; Carossa, S.; Mussano, F.; Munaron, L. The Crosstalk between Osteodifferentiating Stem Cells and Endothelial Cells Promotes Angiogenesis and Bone Formation. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanczler, J.M.; Oreffo, R.O.C. Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis: The Potential for Engineering Bone. Eur Cell Mater 2008, 15, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal-Núñez, S.; Lozano, D.; Esbrit, P. Role of Angiogenesis on Bone Formation. Histol Histopathol 2012, 27, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checchi, M.; Stanzani, V.; Truocchio, S.; Corradini, M.; Ferretti, M.; Palumbo, C. From Morphological Basic Research to Proposals for Regenerative Medicine through a Translational Perspective. Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology 2022, 126, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, C.; Cavani, F.; Sena, P.; Benincasa, M.; Ferretti, M. Osteocyte Apoptosis and Absence of Bone Remodeling in Human Auditory Ossicles and Scleral Ossicles of Lower Vertebrates: A Mere Coincidence or Linked Processes? Calcif Tissue Int 2012, 90, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, M.; Palumbo, C. Static Osteogenesis versus Dynamic Osteogenesis: A Comparison between Two Different Types of Bone Formation. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health The Public Health Service Responds to Commonly Asked Questions. ILAR J 1991, 33, 68–70. [CrossRef]

- Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Policy for Use of Avian Embryos; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elaroussi, M.A.; DeLuca, H.F. Calcium Uptake by Chorioallantoic Membrane: Effects of Vitamins D and K. Endocrinol. Metab 1994, 267, E837–E841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, R.; Ono, T. Regulation of Extraembryonic Calcium Mobilization by the Developing Chick Embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1986, 97, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Packard, M.J. Mobilization of Shell Calcium by Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane in Vitro. J. exp. Biol 1994, 190, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Maibier, M.; Reglin, B.; Nitzsche, B.; Xiang, W.; Rong, W.W.; Hoffmann, B.; Djonov, V.; Secomb, T.W.; Pries, A.R. Structure and Hemodynamics of Vascular Networks in the Chorioallantoic Membrane of the Chicken. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2016, 311, H913–H926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qu, H.; Ji, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Shu, D.; Luo, C. Characterization of the Exosomes in the Allantoic Fluid of the Chicken Embryo. Can J Anim Sci 2021, 101, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.; Labas, V.; Nys, Y.; Rehault-Godbert, S. Investigating Proteins and Proteases Composing Amniotic and Allantoic Fluids during Chicken Embryonic Development. Poult Sci 2017, 96, 2931–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, V.; Hamilton, H.L. A Series of Normal Stages in the Development of the Chick Embryo. J Morphol 1951, 88, 49–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, P.; Casar, B. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as an in Vivo Model to Study Metastasis. Bio Protoc 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarovici, P.; Lahiani, A.; Gincberg, G.; Haham, D.; Marcinkiewicz, C.; Lelkes, P.I. Nerve Growth Factor-Induced Angiogenesis: 2. The Quail Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay. In Neurotrophic Factors: Methods and Protocols; Skaper, S.D., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2018; Vol. 1727, pp. 251–259. ISBN 978-1-4939-7571-6. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons-Wingerter, P.; Lwai, B.; Che Yang, M.; Elliott, K.E.; Milaninia, A.; Redlitz, A.; Clark, J.I.; Helene Sage, E. A Novel Assay of Angiogenesis in the Quail Chorioallantoic Membrane: Stimulation by BFGF and Inhibition by Angiostatin According to Fractal Dimension and Grid Intersection; 1998; Vol. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kundeková, B.; Máčajová, M.; Meta, M.; Čavarga, I.; Bilčík, B. Chorioallantoic Membrane Models of Various Avian Species: Differences and Applications. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, S. V.; Berlow, N.E.; Price, L.H.; Mansoor, A.; Cairo, S.; Rugonyi, S.; Keller, C. Preclinical Therapeutics Ex Ovo Quail Eggs as a Biomimetic Automation-Ready Xenograft Platform. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusimbo, W.S.; Leighton, F.A.; Wobeser, G.A. Histology and Ultrastructure of the Chorioallantoic Membrane of the Mallard Duck (Anas Platyrhynchos). Anatomical Record 2000, 259, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundeková, B.; Máčajová, M.; Meta, M.; Čavarga, I.; Bilčík, B. Chorioallantoic Membrane Models of Various Avian Species: Differences and Applications. Biology (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, C.R.; Wiesmann, N.; Tanner, R.C.; Brieger, J.; Eckrich, J. The Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay in Nanotoxicological Research - an Alternative for in Vivo Experimentation. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longenecker, B.M.; Pazderka, F.; Stone, H.S.; Gavora, J.S.; Ruth, R.F. In Ovo Assay for Marek’s Disease Virus and Turkey Herpesvirus. 1975, 11, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janser, F.; Ney, P.; Pinto, M.; Langer, R.; Tschan, M. The Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assay as a Three-Dimensional Model to Study Autophagy in Cancer Cells. Bio Protoc 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Arai, F.; Kawahara, T. Egg-in-Cube: Design and Fabrication of a Novel Artificial Eggshell with Functionalized Surface. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohle, D.S.; Pasa, S.D.; Gustmann, S.; Laub, M.; Wissler, J.H.; Jennissen, H.P.; Dünker, N. Chick Ex Ovo Culture and Ex Ovo CAM Assay: How It Really Works. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gareta, E.; Binkowska, J.; Kohli, N.; Sharma, V. Towards the Development of a Novel Ex Ovo Model of Infection to Pre-Screen Biomaterials Intended for Treating Chronic Wounds. J Funct Biomater 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.; Dungel, P.; Reischies, F.M.J.; Rohringer, S.; Slezak, P.; Smolle, C.; Spendel, S.; Kamolz, L.P.; Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy, N.; Schicho, K. Photobiomodulation (PBM) Promotes Angiogenesis in-Vitro and in Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Model. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consen Egg Anatomy. Available online: https://www.theperfectegg.net/the-onsen-egg-temperature-curve/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Gómez Del Moral, M.; Fonfría, J.; Varas, A.; Jiménez, E.; Moreno, J.; Zapata, A.G. Appearance and Development of Lymphoid Cells in the Chicken (Gallus Gallus) Caecal Tonsil. Anatomical Record 1998, 250, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzi-Rapp, K.; Rück, A.; Kaufmann, R. Characterization of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Model as a Short-Term in Vivo System for Human Skin. Arch Dermatol Res 1999, 291, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Vacca, A.; Presta, M. The Gelatin Sponge-Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak-Sliwinska, P.; Segura, T.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. The Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane Model in Biology, Medicine and Bioengineering. Angiogenesis 2014, 17, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Jiménez, I.; Hulsart-Billstrom, G.; Lanham, S.A.; Janeczek, A.A.; Kontouli, N.; Kanczler, J.M.; Evans, N.D.; Oreffo, R.O.C. The Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assay for the Study of Human Bone Regeneration: A Refinement Animal Model for Tissue Engineering. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBord, L.C.; Pathak, R.R.; Villaneuva, M.; Liu, H.-C.; Harrington, D.A.; Yu, W.; Lewis, M.T.; Sikora, A.G. The Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) as a Versatile Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Platform for Precision Medicine and Preclinical Research. Am J Cancer Res 2018, 8, 1642–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Checchi, M.; Bertacchini, J.; Cavani, F.; Magarò, M.S.; Reggiani Bonetti, L.; Pugliese, G.R.; Tamma, R.; Ribatti, D.; Maurel, D.B.; Palumbo, C. Scleral Ossicles: Angiogenic Scaffolds, a Novel Biomaterial for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Biomater Sci 2020, 8, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzani, V.; Giubilini, A.; Checchi, M.; Bondioli, F.; Messori, M.; Palumbo, C. Eco-Sustainable Approaches in Bone Tissue Engineering: Evaluating the Angiogenic Potential of Different Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate)–Nanocellulose Composites with the Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay. Adv Eng Mater 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. Two New Applications in the Study of Angiogenesis the CAM Assay: Acellular Scaffolds and Organoids. Microvasc Res 2022, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, R.A.; Muenzner, J.K.; Kunze, P.; Geppert, C.I.; Ruebner, M.; Huebner, H.; Fasching, P.A.; Beckmann, M.W.; Bäuerle, T.; Hartmann, A.; et al. The Chorioallantoic Membrane Xenograft Assay as a Reliable Model for Investigating the Biology of Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miebach, L.; Berner, J.; Bekeschus, S. In Ovo Model in Cancer Research and Tumor Immunology. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider-Stock, R.; Ribatti, D. The CAM Assay as an Alternative In Vivo Model for Drug Testing. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2020; Vol. 265, pp. 303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Kunz, P.; Schenker, A.; Sähr, H.; Lehner, B.; Fellenberg, J. Optimization of the Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay as Reliable in Vivo Model for the Analysis of Osteosarcoma. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.Y.; Koh, A.P.F.; Antony, J.; Huang, R.Y.J. Applications of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane as an Alternative Model for Cancer Studies. Cells Tissues Organs 2022, 211, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, M.; Wennhold, K.; Lehmann, J.; Garcia-Marquez, M.; Klein, S.; Kochen, E.; Lohneis, P.; Lechner, A.; Wagener-Ryczek, S.; Plum, P.S.; et al. Cancer-Specific Immune Evasion and Substantial Heterogeneity within Cancer Types Provide Evidence for Personalized Immunotherapy. NPJ Precis Oncol 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Fluegen, G.; Garcia, P.; Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy, N.; Gribaldo, L.; Huang, R.Y.J.; Rasche, V.; Ribatti, D.; Rousset, X.; Pinto, M.T.; et al. The CAM Model—Q&A with Experts. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Pizon, M.; Schott, D.; Pachmann, U.; Schobert, R.; Pizon, M.; Wozniak, M.; Bobinski, R.; Pachmann, K. Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assays as a Model of Patient-Derived Xenografts from Circulating Cancer Stem Cells (CCSCs) in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ishihara, M.; Chin, A.I.; Wu, L. Establishment of Xenografts of Urological Cancers on Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) to Study Metastasis. Precis Clin Med 2019, 2, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Zhou, X.; Ming, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P. Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay: A 3D Animal Model for Study of Human Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiūnienė, N.; Tamašauskas, A.; Valančiūtė, A.; Deltuva, V.; Vaitiekaitis, G.; Gudinavičienė, I.; Weis, J.; Graf Von Keyserlingk, D.; Balčiūnienė, N. Histology of Human Glioblastoma Transplanted on Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane EKSPERIMENTINIAI TYRIMAI. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009, 45, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vézina-Dawod, S.; Perreault, M.; Guay, L.D.; Gerber, N.; Gobeil, S.; Biron, E. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 1,4-Benzodiazepin-3-One Derivatives as Potential Antitumor Agents against Prostate Cancer. Bioorg Med Chem 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goehringer, N.; Biersack, B.; Peng, Y.; Schobert, R.; Herling, M.; Ma, A.; Nitzsche, B.; Höpfner, M. Anticancer Activity and Mechanisms of Action of New Chimeric EGFR/HDAC-Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miebach, L.; Freund, E.; Horn, S.; Niessner, F.; Sagwal, S.K.; von Woedtke, T.; Emmert, S.; Weltmann, K.D.; Clemen, R.; Schmidt, A.; et al. Tumor Cytotoxicity and Immunogenicity of a Novel V-Jet Neon Plasma Source Compared to the KINPen. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, P.; Schenker, A.; Sähr, H.; Lehner, B.; Fellenberg, J. Optimization of the Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay as Reliable in Vivo Model for the Analysis of Osteosarcoma. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liedtke, K.R.; Freund, E.; Hermes, M.; Oswald, S.; Heidecke, C.D.; Partecke, L.I.; Bekeschus, S. Gas Plasma-Conditioned Ringer’s Lactate Enhances the Cytotoxic Activity of Cisplatin and Gemcitabine in Pancreatic Cancer in Vitro and in Ovo. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privat-Maldonado, A.; Verloy, R.; Cardenas Delahoz, E.; Lin, A.; Vanlanduit, S.; Smits, E.; Bogaerts, A. Cold Atmospheric Plasma Does Not Affect Stellate Cells Phenotype in Pancreatic Cancer Tissue in Ovo. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.; Papior, D.; Stephan, H.; Dönker, N. Characterization of Etoposide- and Cisplatin-Chemoresistant Retinoblastoma Cell Lines. Oncol Rep 2018, 39, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabipov, A.; Freund, E.; Liedtke, K.R.; Käding, A.; Riese, J.; van der Linde, J.; Kersting, S.; Partecke, L.I.; Bekeschus, S. Murine Macrophages Modulate Their Inflammatory Profile in Response to Gas Plasma-Inactivated Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achkar, I.W.; Kader, S.; Dib, S.S.; Junejo, K.; Al-Bader, S.B.; Hayat, S.; Bhagwat, A.M.; Rousset, X.; Wang, Y.; Viallet, J.; et al. Metabolic Signatures of Tumor Responses to Doxorubicin Elucidated by Metabolic Profiling in Ovo. Metabolites 2020, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, G.; Koch, A.B.F.; Löffler, J.; Jelezko, F.; Lindén, M.; Li, H.; Abaei, A.; Zuo, Z.; Beer, A.J.; Rasche, V. In Vivo PET/MRI Imaging of the Chorioallantoic Membrane. Front Phys 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Koyanagi-Aoi, M.; Maniwa, Y.; Aoi, T. Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay Revealed the Role of TIPARP (2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-Dioxin-Inducible Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase) in Lung Adenocarcinoma-Induced Angiogenesis. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as an Experimental Model to Study in Vivo Angiogenesis in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Brain Res Bull 2022, 182, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanskienė, E.; Balnytė, I.; Valančiūtė, A.; Alonso, M.M.; Preikšaitis, A.; Stakišaitis, D. The Different Temozolomide Effects on Tumorigenesis Mechanisms of Pediatric Glioblastoma PBT24 and SF8628 Cell Tumor in CAM Model and on Cells In Vitro. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhoff, M.; Grunewald, S.; Schaefer, C.; Zöllner, S.K.; Plaumann, P.; Busch, M.; Dünker, N.; Ketzer, J.; Kersting, J.; Bauer, S.; et al. Evaluation of the Effect of Photodynamic Therapy on CAM-Grown Sarcomas. Bioengineering 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guder, W.K.; Hartmann, W.; Buhles, C.; Burdack, M.; Busch, M.; Dünker, N.; Hardes, J.; Dirksen, U.; Bauer, S.; Streitbürger, A. 5-ALA-Mediated Fluorescence of Musculoskeletal Tumors in a Chick Chorio-Allantoic Membrane Model: Preclinical in Vivo Qualification Analysis as a Fluorescence-Guided Surgery Agent in Orthopedic Oncology. J Orthop Surg Res 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, K.; Lin, L.; Qian, F.; Li, P.; Zhu, L.; Cai, H.; You, L.; Song, J.; Kok, S.H.L.; et al. Reversine Suppresses Osteosarcoma Cell Growth through Targeting BMP-Smad1/5/8-Mediated Angiogenesis. Microvasc Res 2021, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialho, S.L.; Silvestrini, B.R.; Vieira, J.; Paiva, M.R.B.; Silva, L.M.; Chahud, F.; Silva-Cunha, A.; Correa, Z.M.; Jorge, R. Successful Growth of Fresh Retinoblastoma Cells in Chorioallantoic Membrane. Int J Retina Vitreous 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlos Rodrigo, M.A.; Casar, B.; Michalkova, H.; Jimenez Jimenez, A.M.; Heger, Z.; Adam, V. Extending the Applicability of In Ovo and Ex Ovo Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane Assays to Study Cytostatic Activity in Neuroblastoma Cells. Front Oncol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S.E.; Herrmann, A.; Shaw, L.; Gash, E.N.; Poptani, H.; Sacco, J.J.; Coulson, J.M. The Chick Embryo Xenograft Model for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: A Cost and Time Efficient 3Rs Model for Drug Target Evaluation. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, B.T.; Shahin, S.A.; Croissant, J.; Fatieiev, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Le-Hoang Doan, T.; Yik, T.; Simargi, S.; Conteras, A.; Ratliff, L.; et al. Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay as an in Vivo Model to Study the Effect of Nanoparticle-Based Anticancer Drugs in Ovarian Cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider-Stock, R.; Flügen, G. Editorial for Special Issue: The Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Model - Traditional and State-of-the Art Applications: The 1st International CAM Conference. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangieri, D.; Nico, B.; Benagiano, V.; De Giorgis, M.; Vacca, A.; Ribatti, D. Angiogenic Activity of Multiple Myeloma Endothelial Cells in Vivoin the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Assayis Associated to a Down-Regulation in the Expression of Endogenous Endostatin. J. Cell. Mol. Med 2008, 12, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, S.M.; Cheresh, D.A. Tumor Angiogenesis: Molecular Pathways and Therapeutic Targets. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The Hallmarks of Cancer Review Evolve Progressively from Normalcy via a Series of Pre. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, J. Tumor Angiogenesis: Therapeutic Implications. N Engl J Med. 1971, 285, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demcisakova, Z.; Luptakova, L.; Tirpakova, Z.; Kvasilova, A.; Medvecky, L.; De Spiegelaere, W.; Petrovova, E. Evaluation of Angiogenesis in an Acellular Porous Biomaterial Based on Polyhydroxybutyrate and Chitosan Using the Chicken Ex Ovo Chorioallantoic Membrane Model. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, S.M.; Murphy, T.J.; Thai, S.N.M.; Eichmann, A.; Alva, J.A.; Luisa Iruela-Arispe, M. Selective Binding of Lectins to Embryonic Chicken Vasculature. The Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 2003, 51, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, M.; Balke, M.; Schmidt, A.; Bloch, W.; Kurz, H.; Javerzat, S.; Rousseau, B.; Wilting, J.; Bikfalvi, A. VEGF Coordinates Interaction of Pericytes and Endothelial Cells During Vasculogenesis and Experimental Angiogenesis. Developmental Dynamics 2004, 230, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinaccio, C.; Nico, B.; Ribatti, D. Differential Expression of Angiogenic and Anti-Angiogenic Molecules in the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane and Selected Organs during Embryonic Development. International Journal of Developmental Biology 2013, 57, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D.; Alessandri, G.; Baronio, M.; Raffaghello, L.; Cosimo, E.; Marimpietri, D.; Montaldo, P.G.; De Falco, G.; Caruso, A.; Vacca, A.; et al. Inhibition of Neuroblastoma-Induced Angiogenesis by Fenretinide. Int J Cancer 2001, 94, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanmardi, S.; Aghamaali, M.; Abolmaali, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Tamaddon, AM. MiR-21, An Oncogenic Target MiRNA for Cancer Therapy: Molecular Mechanisms and Recent Advancements in Chemo and Radio-Resistance. Curr Gene Ther. 2017, 16, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalraj, S.; Subramanian, R.; Saravanan, S.; Arumugam, B.; Anuradha, D. MicroRNA-432-5p Regulates Sprouting and Intussusceptive Angiogenesis in Osteosarcoma Microenvironment by Targeting PDGFB. Laboratory Investigation 2021, 101, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, S.; Iyer, A.K.; Weiler, J.; Morrissey, D. V.; Amiji, M.M. Combination of SiRNA-Directed Gene Silencing with Cisplatin Reverses Drug Resistance in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2013, 2, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Blansit, K.; Kiet, T.; Sherman, A.; Wong, G.; Earle, C.; Bourguignon, L.Y.W. The Inhibition of MiR-21 Promotes Apoptosis and Chemosensitivity in Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2014, 132, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmardi, S.; Abolmaali, S.S.; Mehrabanpour, M.J.; Aghamaali, M.R.; Tamaddon, A.M. PEGylated Nanohydrogels Delivering Anti-MicroRNA-21 Suppress Ovarian Tumor-Associated Angiogenesis in Matrigel and Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane Models. BioImpacts 2022, 12, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, F.; Wang, B.; Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, L.; Lu, X.; Xu, W.; Lu, L.; et al. STAT3-Regulated Exosomal MiR-21 Promotes Angiogenesis and Is Involved in Neoplastic Processes of Transformed Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Cancer Lett 2016, 370, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tome, Y.; Kimura, H.; Kiyuna, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Tsuchiya, H.; Kanaya, F.; Bouvet, M.; Hoffman, R.M. Disintegrin Targeting of an α v β 3 Integrin-over-Expressing High-Metastatic Human Osteosarcoma with Echistatin Inhibits Cell Proliferation, Migration, Invasion and Adhesion in Vitro. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46315–46320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maacha, S.; Saule, S. Evaluation of Tumor Cell Invasiveness in Vivo: The Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay. In Methods in Molecular Biology - Chapter 8; Humana Press Inc., 2018; Vol. 1749, pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, P.Y.; Koh, A.P.F.; Antony, J.; Huang, R.Y.J. Applications of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane as an Alternative Model for Cancer Studies. Cells Tissues Organs 2022, 211, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shioda, T.; Munn, L.L.; Fenner, M.H.; Jain, R.K.; Isselbacher, K.J. Early Events of Metastasis in the Microcirculation Involve Changes in Gene Expression of Cancer Cells Tracking MRNA Levels of Metastasizing Cancer Cells in the Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane. American Journal of Patholog 1997, 150. [Google Scholar]

- Cecilia Subauste, M.; Kupriyanova, T.A.; Conn, E.M.; Ardi, V.C.; Quigley, J.P.; Deryugina, E.I. Evaluation of Metastatic and Angiogenic Potentials of Human Colon Carcinoma Cells in Chick Embryo Model Systems. Clin Exp Metastasis 2009, 26, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deryugina, E.I.; Zijlstra, A.; Partridge, J.J.; Kupriyanova, T.A.; Madsen, M.A.; Papagiannakopoulos, T.; Quigley, J.P. Unexpected Effect of Matrix Metalloproteinase Down-Regulation on Vascular Intravasation and Metastasis of Human Fibrosarcoma Cells Selected in Vivo for High Rates of Dissemination. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 10959–10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deryugina, E.I.; Quigley, J.P. Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Model Systems to Study and Visualize Human Tumor Cell Metastasis. Histochem Cell Biol 2008, 130, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.A.; Muenzner, J.K.; Kunze, P.; Geppert, C.I.; Ruebner, M.; Huebner, H.; Fasching, P.A.; Beckmann, M.W.; Bäuerle, T.; Hartmann, A.; et al. The Chorioallantoic Membrane Xenograft Assay as a Reliable Model for Investigating the Biology of Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, E.; Ana Lacalle, R.; Gómez-Moutón, C.; Leonardo, E.; Mañes, S. Quantitative Determination of Tumor Cell Intravasation in a Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction-Based Assay. Clin Exp Metastasis 2002, 19, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, A.; Mellor, R.; Panzarella, G.; Aimes, R.; Hooper, J.; Marchenko, N.; Quigley, J. A Quantitative Analysis of Rate-Limiting Steps in the Metastatic Cascade Using Human-Specific Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 7083–7092. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, R.; Alhussain, H.; Hasan, A.; Ahmed, M.B.; Yalcin, H.C.; Al Moustafa, A.E. A Novel in Ovo Model to Study Cancer Metastasis Using Chicken Embryos and GFP Expressing Cancer Cells. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2020, 20, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Osl, F.; Friess, T.; Stockinger, H.; Scheuer, W. V Quantification of Human Alu Sequences by Real-Time PCR-an Improved Method to Measure Therapeutic Efficacy of Anti-Metastatic Drugs in Human Xenotransplants. Clin Exp Metastasis 2002, 19, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yu, W.; Kovalski, K.; Ossowski, L. Requirement for Specific Proteases in Cancer Cell Intravasation as Revealed by a Novel Semiquantitative PCR-Based Assay. Cell 1998, 94, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Koshida, K.; Endo, Y.; Imao, T.; Uchibayashi, T.; Sasaki, T.; Namiki, M. Basic Science A Chick Embryo Model for Metastatic Human Prostate Cancer. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, A.; Matsumoto, K.; Saito, T.; Muto, M.; Tamanoi, F. Patient Derived Chicken Egg Tumor Model (PDcE Model): Current Status and Critical Issues. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcion, G.; Hermetet, F.; Neiers, F.; Uyanik, B.; Dondaine, L.; Dias, A.M.M.; Da Costa, L.; Moreau, M.; Bellaye, P.S.; Collin, B.; et al. Nanofitins Targeting Heat Shock Protein 110: An Innovative Immunotherapeutic Modality in Cancer. Int J Cancer 2021, 148, 3019–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, M.A.; Sathe, A.; Romano, A.; Hoffmann, M.J.; Schulz, W.A.; van Koeveringe, G.A.; Albers, P.; Nawroth, R.; Niegisch, G. Applying the Chicken Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane Assay to Study Treatment Approaches in Urothelial Carcinoma. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2017, 35, 544.e11–544.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swadi, R.; Mather, G.; Pizer, B.L.; Losty, P.D.; See, V.; Moss, D. Optimising the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane Xenograft Model of Neuroblastoma for Drug Delivery. BMC Cancer 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckrich, J.; Kugler, P.; Buhr, C.R.; Ernst, B.P.; Mendler, S.; Baumgart, J.; Brieger, J.; Wiesmann, N. Monitoring of Tumor Growth and Vascularization with Repetitive Ultrasonography in the Chicken Chorioallantoic-Membrane-Assay. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, P.; Couvet, M.; Vanwonterghem, L.; Henry, M.; Vollaire, J.; Baulin, V.; Werner, M.; Orlowska, A.; Josserand, V.; Mahuteau-Betzer, F. The Pyrrolopyrimidine Colchicine-Binding Site Agent PP-13 Reduces the Metastatic Dissemination of Invasive Cancer Cells in Vitro and in Vivo. Biochem Pharmacol 2019, 160, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleibeuker, E.A.; ten Hooven, M.A.; Castricum, K.C.; Honeywell, R.; Griffioen, A.W.; Verheul, H.M.; Slotman, B.J.; Thijssen, V.L. Optimal Treatment Scheduling of Ionizing Radiation and Sunitinib Improves the Antitumor Activity and Allows Dose Reduction. Cancer Med 2015, 4, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimpietri, D.; Brignole, C.; Nico, B.; Pastorino, F.; Pezzolo, A.; Piccardi, F.; Cilli, M.; Di Paolo, D.; Pagnan, G.; Longo, L.; et al. Combined Therapeutic Effects of Vinblastine and Rapamycin on Human Neuroblastoma Growth, Apoptosis, and Angiogenesis. Clinical Cancer Research 2007, 13, 3977–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marimpietri, D.; Nico, B.; Vacca, A.; Mangieri, D.; Catarsi, P.; Ponzoni, M.; Ribatti, D. Synergistic Inhibition of Human Neuroblastoma-Related Angiogenesis by Vinblastine and Rapamycin. Oncogene 2005, 24, 6785–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ademii, H.; Shinde, D.A.; Gassmann, M.; Gerst, D.; Chaachouay, H.; Vogel, J.; Gorr, T.A. Targeting Neovascularization and Respiration of Tumor Grafts Grown on Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membranes. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katrancioglu, N.; Karahan, O.; Kilic, A.T.; Altun, A.; Katrancioglu, O.; Polat, Z.A. The Antiangiogenic Effects of Levosimendan in a CAM Assay. Microvasc Res 2012, 83, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademhosseini, A.; Langer, R. A Decade of Progress in Tissue Engineering. Nat Protoc 2016, 11, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocholata, P.; Kulda, V.; Babuska, V. Fabrication of Scaffolds for Bone-Tissue Regeneration. Materials 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donderwinkel, I.; Tuan, R.S.; Cameron, N.R.; Frith, J.E. Tendon Tissue Engineering: Current Progress towards an Optimized Tenogenic Differentiation Protocol for Human Stem Cells. Acta Biomater 2022, 145, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Ding, J. Biomaterial–Related Cell Microenvironment in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Engineering 2022, 13, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, D.; Yu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhao, Y. Developing Tissue Engineering Strategies for Liver Regeneration. Engineered Regeneration 2022, 3, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, E.; Amaral, R. do; Blayney, A.W.; Walsh, R.M.C.; O’Brien, F.J.; O’Leary, C. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Strategies for the Repair of Tympanic Membrane Perforations. Biomaterials and Biosystems 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zou, L.; Chen, J. New Perspectives: In-Situ Tissue Engineering for Bone Repair Scaffold. Compos B Eng 2020, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjunan, A.; Baroutaji, A.; Robinson, J.; Wang, C. Tissue Engineering Concept. In Encyclopedia of Smart Materials; Olabi, A.-G., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2022; ISBN 978-0-12-815733-6. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, C.; Kraus, X.; Heene, S.; Loewner, S.; Stanislawski, N.; Cholewa, F.; Blume, H. Vascular Implants – New Aspects for in Situ Tissue Engineering. Eng Life Sci 2022, 22, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, T.; Kang, W.; Li, J.; Yu, L.; Ge, S. An in Situ Tissue Engineering Scaffold with Growth Factors Combining Angiogenesis and Osteoimmunomodulatory Functions for Advanced Periodontal Bone Regeneration. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Li, P.; Li, H.; Gao, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Chen, W.; Liao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Cao, F.; et al. The Application of Bioreactors for Cartilage Tissue Engineering: Advances, Limitations, and Future Perspectives. Stem Cells Int 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisic, M.; Marsano, A.; Maidhof, R.; Wang, Y.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Cardiac Tissue Engineering Using Perfusion Bioreactor Systems. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 719–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todros, S.; Spadoni, S.; Maghin, E.; Piccoli, M.; Pavan, P.G. A Novel Bioreactor for the Mechanical Stimulation of Clinically Relevant Scaffolds for Muscle Tissue Engineering Purposes. Processes 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montorsi, M.; Genchi, G.G.; De Pasquale, D.; De Simoni, G.; Sinibaldi, E.; Ciofani, G. Design, Fabrication, and Characterization of a Multimodal Reconfigurable Bioreactor for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng 2022, 119, 1965–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Meng, C.; Ding, Q.; Yu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Tian, W.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, X.; Wu, B.; et al. In Situ Bone Regeneration with Sequential Delivery of Aptamer and BMP2 from an ECM-Based Scaffold Fabricated by Cryogenic Free-Form Extrusion. Bioact Mater 2021, 6, 4163–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, B.K.; Robert, M.C.; Simpson, F.C.; Malhotra, K.; Jacques, L.; Labarre, P.; Griffith, M. In Situ Tissue Regeneration in the Cornea from Bench to Bedside. Cells Tissues Organs 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periayah, M.H.; Halim, A.S.; Saad, A.Z.M. Chitosan: A Promising Marine Polysaccharide for Biomedical Research. Pharmacogn Rev 2016, 10, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, M. Bioengineering - A Conceptual Approach; Springer: Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, N.; Sharma, V.; Orera, A.; Sawadkar, P.; Owji, N.; Frost, O.G.; Bailey, R.J.; Snow, M.; Knowles, J.C.; Blunn, G.W.; et al. Pro-Angiogenic and Osteogenic Composite Scaffolds of Fibrin, Alginate and Calcium Phosphate for Bone Tissue Engineering. J Tissue Eng 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldeeb, A.E.; Salah, S.; Elkasabgy, N.A. Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications and Current Updates in the Field: A Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AL-Hamoudi, F.; Rehman, H.U.; Almoshawah, Y.A.; Talari, A.C.S.; Chaudhry, A.A.; Reilly, G.C.; Rehman, I.U. Bioactive Composite for Orbital Floor Repair and Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Annese, T.; Tamma, R. The Use of the Chick Embryo CAM Assay in the Study of Angiogenic Activiy of Biomaterials. Microvasc Res 2020, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Roux, B.M.; Posukonis, M.; Bodamer, E.; Brey, E.M.; Fisher, J.P.; Dean, D. Effect of Prevascularization on in Vivo Vascularization of Poly(Propylene Fumarate)/Fibrin Scaffolds. Biomaterials 2016, 77, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignjatovic, N.; Ajdukovic, Z.; Uskokovic, D. New Biocomposite [Biphasic Calcium Phosphate/ Poly-DL-Lactide-Co-Glycolide/Biostimulative Agent] Filler for Reconstruction of Bone Tissue Changed by Osteoporosis. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2005, 16, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, K.; Storck, K.; Muhr, C.; Mayer, H.; Regn, S.; Staudenmaier, R.; Wiese, H.; Maier, G.; Bauer-Kreisel, P.; Blunk, T. Development of Volume-Stable Adipose Tissue Constructs Using Polycaprolactone-Based Polyurethane Scaffolds and Fibrin Hydrogels. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2016, 10, E409–E418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagemann, J.C.; Chung, H.W.; Mrosek, E.H.; Stone, J.J.; Fitzsimmons, J.S.; O’Driscoll, S.W.; Reinholz, G.G. Poly-ε-Caprolactone/Gel Hybrid Scaffolds for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A 2010, 93, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, J.A.; Vikingsson, L.; Gomez Ribelles, J.L.; Sencadas, V.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Fatigue Prediction in Fibrin Poly-ε-Caprolactone Macroporous Scaffolds. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2013, 28, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.Z.; Ni, P.Y.; Wang, B.Y.; Chu, B.Y.; Zheng, L.; Luo, F.; Luo, J.C.; Qian, Z.Y. Injectable and Thermo-Sensitive PEG-PCL-PEG Copolymer/Collagen/n-HA Hydrogel Composite for Guided Bone Regeneration. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 4801–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Chem Rev 2001, 101, 1869–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocak, F.Z.; Talari, A.C.S.; Yar, M.; Rehman, I.U. In-Situ Forming Ph and Thermosensitive Injectable Hydrogels to Stimulate Angiogenesis: Potential Candidates for Fast Bone Regeneration Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde-González, A.; Glinka, M.; Dutta, D.; Wallace, R.; Callanan, A.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Bradley, M. Rapid Fabrication and Screening of Tailored Functional 3D Biomaterials: Validation in Bone Tissue Repair – Part II. Biomaterials Advances 2023, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okesola, B.O.; Mendoza-Martinez, A.K.; Cidonio, G.; Derkus, B.; Boccorh, D.K.; Osuna De La Peña, D.; Elsharkawy, S.; Wu, Y.; Dawson, J.I.; Wark, A.W.; et al. De Novo Design of Functional Coassembling Organic-Inorganic Hydrogels for Hierarchical Mineralization and Neovascularization. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 11202–11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Heupt, L.K.; Wiesmann-Imilowski, N.; Schröder, S.; Groß, J.; Ziskoven, P.C.; Bani, P.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Schiegnitz, E.; Eckelt, A.; Eckelt, J.; et al. Oxygen-Releasing Hyaluronic Acid-Based Dispersion with Controlled Oxygen Delivery for Enhanced Periodontal Tissue Engineering. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesa, F.L.; Aneiros, J.; Cabrera, A.; Bravo, M.; Caballero, T.; Revelles, F.; Del Moral, R.G.; O’Valle, F.J. Antiproliferative Effect of Topic Hyaluronic Acid Gel. Study in Gingival Biopsies of Patients with Periodontal Disease. Histol Histopathol 2002, 17, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eick, S.; Renatus, A.; Heinicke, M.; Pfister, W.; Stratul, S.-I.; Jentsch, H. Hyaluronic Acid as an Adjunct After Scaling and Root Planing: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. J Periodontol 2013, 84, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S.; Arango-Ospina, M.; Rehder, F.; Moghaddam, A.; Simon, R.; Merle, C.; Renkawitz, T.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Westhauser, F. In Vitro and in Ovo Impact of the Ionic Dissolution Products of Boron-Doped Bioactive Silicate Glasses on Cell Viability, Osteogenesis and Angiogenesis. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.X.; Li, Y.M.; Han, D. Co-Substitution of Carbonate and Fluoride in Hydroxyapatite: Effect on Substitution Type and Content. Front Mater Sci 2015, 9, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, A.B.; Zhuang, H.; Baig, A.A.; Higuchi, W.I. Effect of Fluoride Pretreatment on the Solubility of Synthetic Carbonated Apatite. Calcif Tissue Int 2003, 72, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.; Barick, K.C.; Shetake, N.G.; Pandey, B.N.; Hassan, P.A. Citrate-Functionalized Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles for PH-Responsive Drug Delivery. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 77968–77976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Aamer, S.; Chaudhry, A.A.; Wong, F.S.L.; Rehman, I.U. Synthesis and Characterizations of a Fluoride-Releasing Dental Restorative Material. Materials Science and Engineering C 2013, 33, 3458–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Mota, M.; De, V.; Branco, A. Polyurethane-Based Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Regeneration. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bongio, M.; Lopa, S.; Gilardi, M.; Bersini, S.; Moretti, M. A 3D Vascularized Bone Remodeling Model Combining Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts in a CaP Nanoparticle-Enriched Matrix. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 1073–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadic, D.; Epple, M. A Thorough Physicochemical Characterisation of 14 Calcium Phosphate-Based Bone Substitution Materials in Comparison to Natural Bone. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D Biomaterial Scaffolds and Osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, A.-L.; Pion, E.; Troebs, J.; Lenze, U.; Prantl, L.; Htwe, M.M.; Phyo, A.; Haerteis, S.; Aung, T. Extended Analysis of Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Primary Osteosarcoma Tissue Using 3D- in-Vivo-Tumor-Model. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2020, 76, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanczler, J.M.; Smith, E.L.; Roberts, C.A.; Oreffo, R.O.C. A Novel Approach for Studying the Temporal Modulation of Embryonic Skeletal Development Using Organotypic Bone Cultures and Microcomputed Tomography. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 2012, 18, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Kanczler, J.; Oreffo, RO. A New Take on an Old Story: Chick Limb Organ Culture for Skeletal Niche Development and Regenerative Medicine Evaluation. Eur Cell Mater. 2013, 11, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.L.; Rashidi, H.; Kanczler, J.M.; Shakesheff, K.M.; Oreffo, R.O.C. The Effects of 1α, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Transforming Growth Factor-Β3 on Bone Development in an Ex Vivo Organotypic Culture System of Embryonic Chick Femora. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisto, S.; Saarela, U.; Dönges, L.; Raykhel, I.; Skovorodkin, I.; Vainio, S.J. Optimization of Renal Organoid and Organotypic Culture for Vascularization, Extended Development, and Improved Microscopy Imaging. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).