1. Introduction

In 2015, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs) were proposed by United Nations to promote actions to end poverty,

protect the planet and ensure people’s peace and prosperity by 2030. The goals

include no poverty, good health and well-being, sustainable cities and

communities, etc. These sustainable issues are believed to be more severe in

rural areas than urban regions due to the less developed transportation, poor

sanitation, and the lack of financial and economic resources (Chaudhuri &

Roy, 2017; Nakamura, Bundervoet & Nuru, 2020; Nakamura, 2022). For a rural

family, a sudden illness may cause the family to lose its labor force and thus

have no source of income, and the expenditure on disease treatment makes it

even more difficult for the family to maintain (Isoto, Sam & Kraybill,

2017). As a result, poor rural households will become poorer, and the gap

between rural and urban areas will continue to widen. Health shock can cause

poverty. Therefore, studying health shock’s impacts on rural household welfare

has a significant implication for rural sustainable development.

There are substantial differences between rural

areas in developing countries and rural areas in developed countries in terms

of income level, social welfare security, and education level (Lagakos, 2020).

We chose the largest developing country China as the sample for several

reasons: (1) as a large agricultural country, China has large tracts of land,

villages, and communities that are still in a rural state, providing a large

number of samples; (2) Chinese government proposed a New Rural Cooperative Medical

System (NRCMS) in 2015 which covered 20% to 60% medical expenditures for rural

households; (3) the spatial and geographic difference is also pronounced in the

case of China and we can compare the impacts in different regions.

Briefly, according to the National Burea of

Statistics, in 2020, China's GDP exceeded 100 trillion yuan, and the per capita

GDP reached 72,447 yuan, but the per capita disposable income in rural areas is

merely 17,131 yuan, indicating a significant urban-rural development gap. In

addition, rural grassroots organizations generally have an incomplete social

security system, and a large number of rural families face excessive medical

burdens, which are more likely to lead to excessive debt. Improving the welfare

and happiness of rural families is taken as one of the most important tasks

that the Chinese government has persisted in for a long time. Therefore, this

paper focuses on the impact of medical borrowing on household welfare when

rural households face health shocks.

We used data from the 2019 China Household Finance

Survey to empirically analyze the impact of borrowing on household welfare

after rural households suffer health shocks. In order to obtain an accurate and

robust research result, we used the OSL least squares method combined with the

propensity score matching method (PSM) to solve the endogeneity issue. Firstly,

the propensity score matching (PSM) method is used to analyze the impact of

borrowing on household welfare; secondly, the group regression method is used

to study rural households in the eastern, central, and western regions.

Our main contributions are: first, this paper

analyzed the impact of borrowing on rural household welfare under health

shocks, including the impact of income, consumption, and employment, which is a

significant supplement to the field of rural development research; second, this

paper examines the heterogeneity of different regions, which can provide a

deeper understanding of the characteristics of rural households in different

regions of China facing health shocks; third, based on the analysis and conclusions,

this paper also provided suggestions regarding rural policies to enhance the

overall well-being, health, and sustainable development of rural areas.

The follow-up content is arranged as follows:

first, review the relevant literature; second, introduce the data, models, and

variables used in this paper; third, analyze the empirical results; finally,

summarize the research conclusions and put forward policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Borrowing and Rural Household Welfare

Views differ on the impact of borrowing on rural

household welfare. On the one hand, it is believed that borrowing can increase rural

household welfare. Tonch & Sohn (2022) suggest that informal borrowing,

which is a more common form of borrowing than formal borrowing in rural areas,

can increase household welfare by 4.3%. Lin, Wang, Gan & Nguyen (2019) also

provide evidence that credit constraint negatively affects rural household

welfare and advises providing more formal borrowing to rural families. Because

borrowing increases disposable family income protects family consumption and

improves family welfare. However, the borrowing under the case of health shock

might be different, which we will illustrate further.

On the other side, some research indicates that

household welfare in rural areas might not be enhanced by borrowings, on the

contrary, the welfare can be even mitigated and it can lead to other issues

such as child labor within the family (Chakrabarty, 2012). The reason is that

in the long term, if the borrowings cannot realize their value in time, the

rural households have to undertake the financial expenses after repaying the

debt. Duong and Thanh (2014) also showed that for low-income groups, loans can

only protect their consumption and can not improve their income well. At the

same time, banks and financial institutions rarely target the poor in the rural

areas, but target the relatively wealthy groups, which will further increase

the gap between the rich and the poor.

However, the general discussion about the impact of

borrowing on rural household welfare might not be convincing enough as we could

hardly observe where the borrowings flow to and whether the borrowings can be

used right and successfully. But health shock provides a certain background for

analyzing borrowing’s impacts on rural household welfare and can lead to a more

certain and convincing result.

2.2. Health Shock and Rural Household Welfare

From the perspective of the dynamics of poverty

caused by illness, Hong and Chang (2010) believed that health shocks would

cause families to fall into temporary poverty in the short term, but the

long-term impact could be very small. However, Alam & Mahal (2014) showed

that in the face of health shocks, households can reduce the incidence of

poverty by borrowing from relatives and friends in the short term, but it would

increase the incidence of poverty in the long run. From the perspective of the

impact of health shocks on household consumption, some scholars have pointed

out that households could smooth consumption in the short term (Liu, 2016;

Mitra, Palmer, Mont & Groce, 2016). However, other scholars have shown that

health shocks had a significant negative impact on household health and

non-health expenditures (Wagstaff & Lindelow, 2014; Asfaw & Braun,

2004). Some scholars believe that after a health shock, the new rural medical

system increased household non-medical expenditures, but had no significant impact

on medical and healthcare expenditures (Bai et al., 2012). In addition, Cheung

& Padieu (2015) showed that the NCMS had a negative impact on savings in

the middle household income, but had no significant impact on the poorest. And

NCMS can significantly reduce the savings of wealthy people when they do not

benefit from other health programs.

We draw much inspiration from the previous

literature on the effects of health shocks and borrowing on households. Due to

the dual structure of urban and rural areas in China, rural residents have a

greater risk exposure than urban residents, especially in the face of greater

vulnerability to health risks. Borrowing is one of the main ways for rural

households to deal with health shocks. However, at present, there is no

in-depth discussion in this field that analyzes the borrowings’ impacts on

rural household welfare under the background of health shocks. Econometrically,

most studies only stay in the traditional instrumental variable method (IV) to

deal with the endogenous problems in the model. With the development of

econometrics in recent years, it is more appropriate to use causal inference

models that are more effective in dealing with endogenous issues (Ichimura

& Taber, 2001). This paper adopted the propensity matching score (PSM)

model, which we would introduce in detail in the following sections. We also

took the geographical differences into consideration and studied the

heterogeneity across different regions of China.

3. Data and Model

3.1. Data and Variables

We used China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) data

provided by the Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance of

Southwestern University of Finance and Economics in 2019. Specifically, the

dataset was collected using a nationwide random sampling survey with large

sample size and high representativeness. Questionnaire question was

"A2025b: Compared with his peers, how is [CAPI load name]'s current

physical condition? 1. Very good, 2. Good, 3. Average, 4. Not good, 5 Very

bad". In this paper, the rural households whose respondents answered “4.

Not good or 5. Very bad” were defined as families suffering from health shocks.

After removing outliers and missing samples of key variables, 12,587 samples

were finally obtained, of which 6,129 samples were affected by health shocks,

and 6,458 samples were not affected by health shocks.

The explained variable was family welfare.

Referring to previous literature, we examined family welfare in three aspects:

first, family income (yuan/year); second, consumption expenditure, including

food expenditure (yuan/year), education expenditure (yuan/year), tourism

expenditure (yuan/year), health care expenditure (yuan/year); the third is

labor participation, including weekly working hours and proportion of the

employed.

The explanatory variable in this paper was whether

to borrow or not after suffering a health shock, with borrowing households

denoted as 1 and non-borrowing households denoted as 0. The control variables

in this paper were owner characteristics, household characteristics, and

household economic variables. The owner characteristic variables include age,

education level, type of household registration, and whether the owner is

employed. Household characteristics include financial literacy, family size, and

average age of the family. The per capita GDP of the province is the household

economic variable.

Table 1 shows

the means of the variables under different groupings. Since this paper mainly

focuses on the impact of borrowing on rural household welfare under health

shocks, the descriptive statistics in this paper only show the mean value of

the sample. It can be seen from

Table 1 that, compared with no health shock, the family welfare of the health shock

group has declined. In terms of income, the average annual income of families

without health shocks is 52,900 yuan, and the average annual income of families

with health shocks is 37,200 yuan, a decrease of 29.7%. From the perspective of

consumption, food expenditures, education expenditures, tourism expenditures,

and health care expenditures all declined, of which the largest decline was in

tourism expenditures and the smallest decline in food expenditures. At the

labor level, both the weekly working hours and the proportion of working people

in households affected by health shocks decreased. In addition, the owners of

households affected by health shocks are older, less educated, and less

financially literate, and the average age of households is older.

Columns 3 and 4 of

Table 1 show borrowed and unborrowed households

under health shocks. The results show that households with borrowing had a

larger decline in welfare, especially household income, but education spending

increased instead. Even if the family suffers a health shock, the family will

try to avoid reducing the quality of education as much as possible. In terms of

household head characteristics and family characteristics, under health shocks,

compared with non-borrowing households, households with borrowings have younger

owners of households, more financial knowledge, larger family size, and lower

average age of households.

3.2. Model

To examine the impacts of health shocks on rural

household welfare, we first write the simple basic regression model as follows:

is the explained variable, i.e., family

welfare; is the explanatory variable, i.e., whether rural

families are affected by health shocks; is the control variable, i.e., family

characteristic variables, household owner characteristic variables, and

provincial dummy variables; and is the stochastic term.

Using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method to

estimate is easy to cause endogeneity problems. In order to solve the possible

endogenous problems in the model, we used the Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

method to match and screen the control group samples. The control group is the

households that have borrowed under the health shock, and the treatment group

is the households that have not borrowed under the health shock. The propensity

score was calculated using the PSM method.

The propensity score is the conditional probability

that a rural household enters the treatment group given the corresponding

control variables:

In equation (2),

is a given control variable and

is a binary variable of whether there is a

borrowing.

indicates that rural households borrow when faced

with health shocks.

means that rural households

will not borrow when faced with a health shock.

indicates the conditional

expectation of rural households entering the treatment group. In order to

obtain the propensity score value, this paper adopts the logit model estimation

method of Dehejia and Wahba (2002):

In formula (3), is the control variable that may affect the

family's entry into the treatment group, and is the coefficient of the control variable. The

propensity score can be estimated by the logit model of the above formula.

In addition, referring to the method of Heckman,

Ichimura, & Todd (1997), this paper adopts the average treatment effect

(ATT) of the treatment group to measure the difference between rural households

that have borrowed when they are hit by a health shock and those who assume

that the household does not have borrowed.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Basic Regression and PSM Results

Table 2 shows

the results of cross-sectional OLS regression, in which model (1) is the result

without adding control variables, model (2) is the result of adding the owner

of household characteristic variables and family characteristic variables, and

model (3) is the result of adding the economic environment variables. The

results show that when rural households face health shocks, borrowing will

significantly reduce household income at the 1% level, significantly reduce

household healthcare expenditure at the 10% level, and significantly reduce the

proportion of household workers at the 1% level. The number of hours worked per

week has also been significantly reduced. After adding control variables,

borrowing significantly reduces household food expenditures but has no

significant impact on education and tourism spending. The possible reason is:

given the condition that the absolute value of rural household income is small,

borrowing is mainly used for treatment, so income and food expenditures are

reduced when facing health shocks. In addition, due to health shocks, they have

to reduce their working hours. There is no significant decrease in education

expenditure, mainly because most families in China regard education as a

significant and necessary expenditure. There is no significant decrease in

tourism expenditure, which may be because rural households have already spent

very little on tourism, which can not be further cut down.

Cross-sectional OLS regression is prone to endogeneity issues, so we used propensity matching score (PSM) estimation to deal with the endogeneity issues. The family characteristic variables and the owner of household characteristic variables affect the family's entry into the treatment group to a certain extent, so we selected the family characteristic variables and the owner of household characteristic variables as matching variables.

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of the matching variables. The propensity score can be calculated by using the matching variables and the logit model.

Next, the common support assumption and the balance test are carried out.

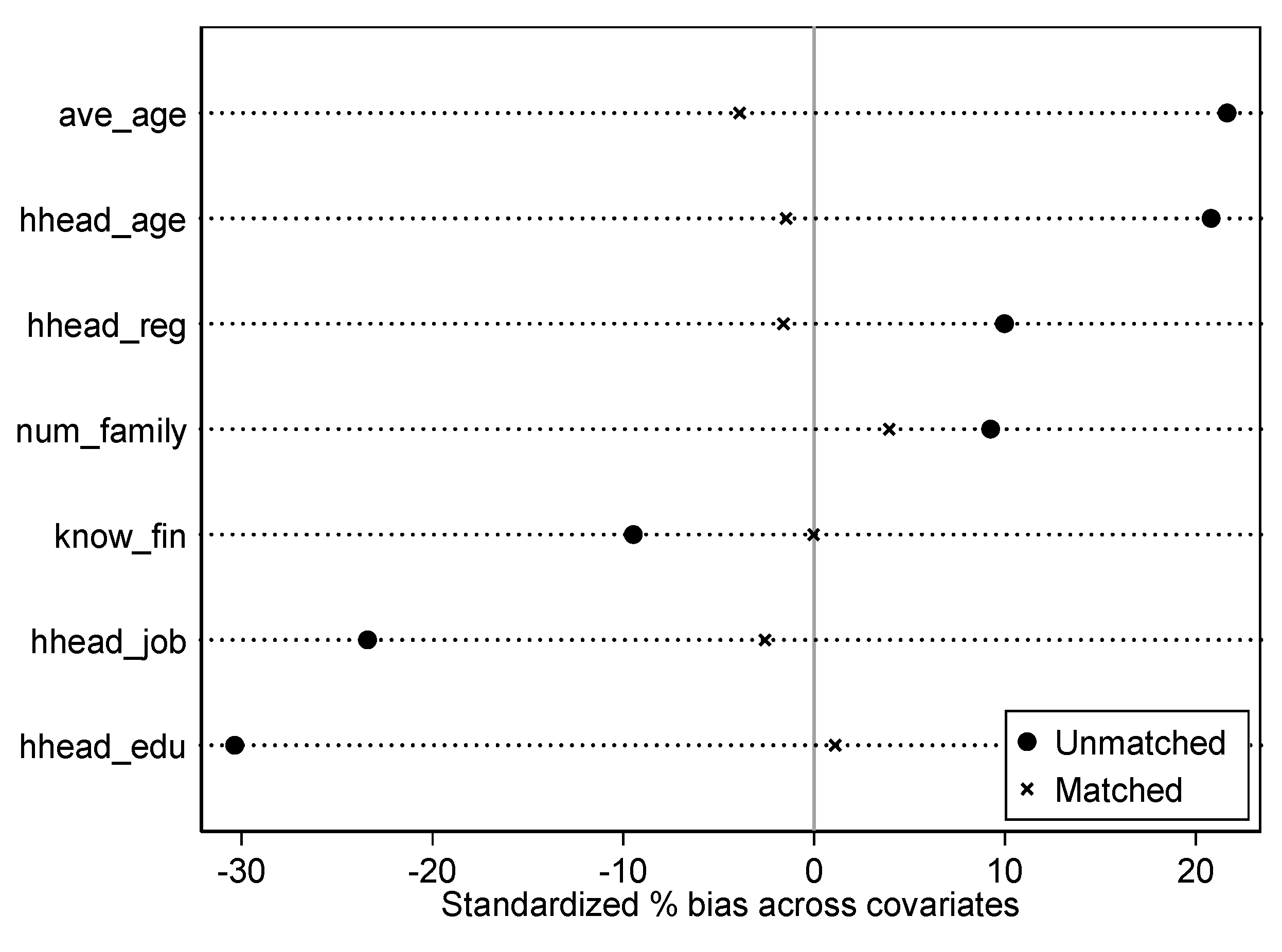

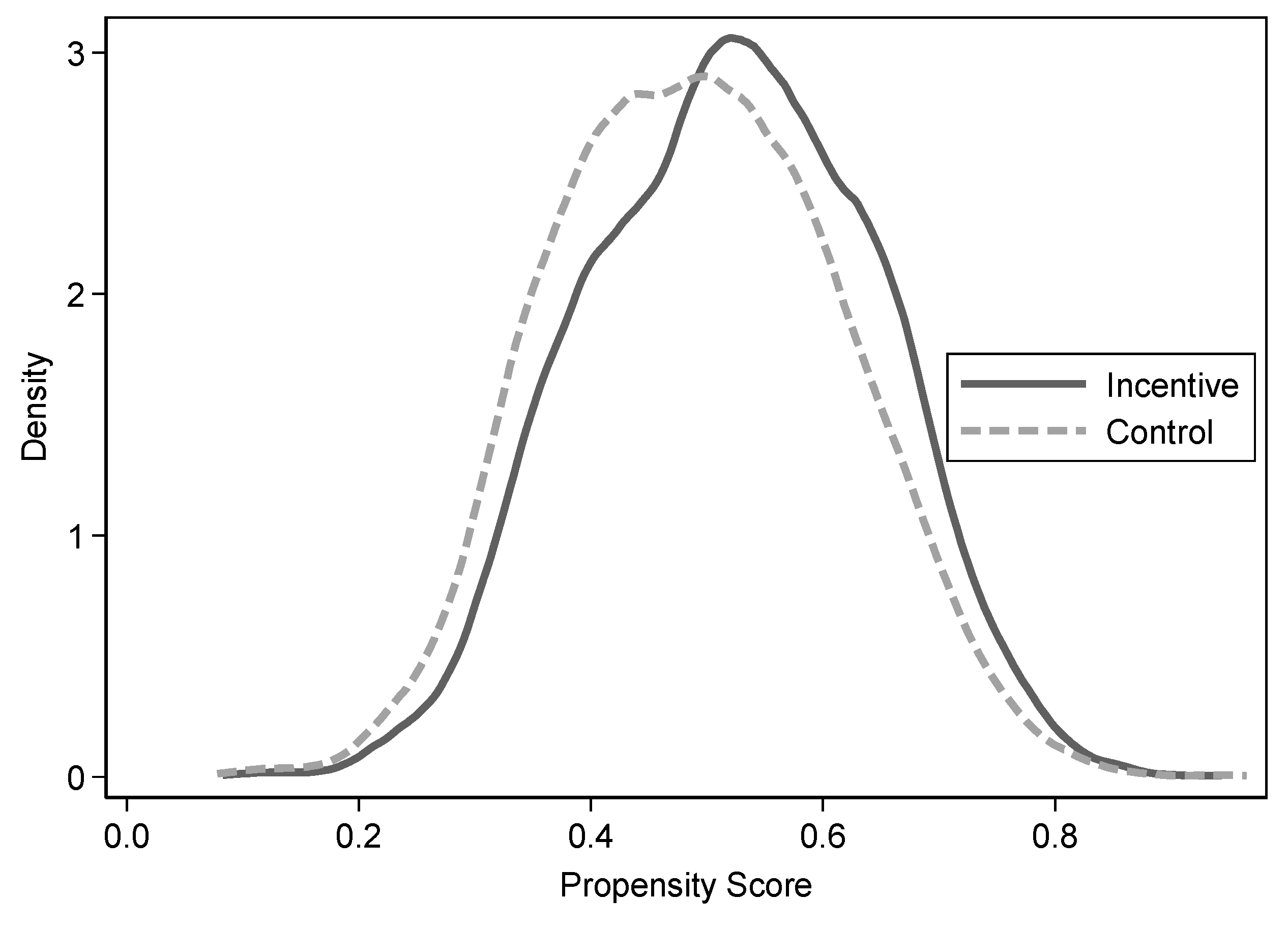

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show the standard deviation and density function plots of the matching variables before and after matching, respectively. It can be seen in

Figure 1 that the standardized deviation is significantly reduced after matching, and in

Figure 2 it can be seen that the two curves before and after matching are close. Therefore, it shows that the matching result is relatively satisfactory.

Propensity score matching (PSM) estimation is then performed.

Table 4 shows the estimated results after using the propensity score matching (PSM) method. The results show that under health shocks, borrowing is significantly negatively correlated to varying degrees with household income, food expenditure, tourism expenditure, health care expenditure, weekly working hours, and the proportion of household workers. There is no significant relationship with education expenditure, which further shows that although the health shock has led to borrowing, the investment in education has not changed significantly.

4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

Next, we examined the impact of borrowing at different regional levels. We divided the provinces, where the sample households lived, into eastern, central, and western regions. The division is based on the relevant policies and regulations of Western Development.

Table 5 shows that when households face health shocks, they have a greater impact on rural areas in the west, especially at the level of household income. The western region is generally more economically backward than the central and eastern regions, and the social welfare system is not as effective as in other regions. Once a health shock occurs, it is more likely to lead to a decline in family welfare in the western regions.

5. Conclusion

Compared with urban households, rural households have weak resilience and high vulnerability when faced with risks. Health shock is a more common and serious risk among various risks that rural households faced. Using data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) 2019, we examined the impact of borrowing on rural household welfare under health shocks. The results of the study showed that: first, when rural households faced health shocks, the health shocks would have an important impact on household income and food expenditure; second, when households faced health shocks, household health care expenditures would decline significantly, indicating that the borrowing is mainly used for the treatment of specific diseases; thirdly, in the heterogeneity analysis, the impact of borrowing on the western region is stronger than the central and east regions. The possible reason is that compared with the eastern and central regions, the economic development of the western region is relatively lagging behind, and the family faces greater financing constraints.

Therefore, at the policy and practice level, it is recommended to further improve social security policies such as medical insurance to protect rural families to a greater extent, so that rural household welfare can continue to enhance and rural development can be more sustainable. At present, when families face health shocks, they borrow more from traditional social networks, but as the birth rate declines, the population ages, and family sizes shrink, social networks gradually weaken. Households will not be able to fully insure against risks, especially under frequent health shocks in rural areas, for the foreseeable future. Therefore, speeding up the establishment of rural finance, especially drawing on the relatively mature microfinance that has been developed in some developed economies, is of great significance for alleviating the financing constraints of the rural population and improving the welfare of rural families.

References

- Alam, & Mahal, A. (2014). Economic impacts of health shocks on households in low and middle income countries: a review of the literature. Globalization and Health, 10(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, & Braun, J. von. (2004). Is Consumption Insured against Illness? Evidence on Vulnerability of Households to Health Shocks in Rural Ethiopia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53(1), 115–129. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Li, & Wu. (2012). Yiliao Baoxian Yu Xiaofei: Laizi Xinxing Nongcun Hezuo Yiliao de Zhengju [Health Insurance and Consumption:Evidence from China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme]. Economic Research Journal, 02, 41-53.

- Chakrabarty, S. 2012. “Does micro credit increase child labour in absence of micro insurance?”ILO Working Paper 12, https://eprints.usq.edu.au/23912/. 2391.

- Chaudhuri, & Roy, M. (2017). Rural-urban spatial inequality in water and sanitation facilities in India: A cross-sectional study from household to national level. Applied Geography (Sevenoaks), 85, 27–38. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, & Padieu, Y. (2015). Heterogeneity of the Effects of Health Insurance on Household Savings: Evidence from Rural China. World Development, 66, 84–103. [CrossRef]

- Dehejia, R.H. and Wahba, S. (2002) Propensity Score-Matching Methods for Nonexperimental Causal Studies. Review Economics and Statistics, 84, 151-161. [CrossRef]

- Duong, & Thanh, P. T. (2014). Impact evaluation of microcredit on welfare of the Vietnamese rural households. Asian Social Science, 11(2), 190–201. [CrossRef]

- Heckman, Ichimura, H., & Todd, P. E. (1997). Matching As An Econometric Evaluation Estimator: Evidence from Evaluating a Job Training Programme. The Review of Economic Studies, 64(4), 605–654. [CrossRef]

- Hong, & Chang. (2010). Woguo Nongcun Jumin Jibing Yu Pinkun De Xianghu Zuoyong Fenxi [Research on Interaction between Diseases and Poverty in China’s Rural Household]. Issues in Agricultural Economy, 31(04):85-94+112. [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, & Taber, C. (2001). Propensity-Score Matching with Instrumental Variables. The American Economic Review, 91(2), 119–124. [CrossRef]

- Isoto, Sam, A. G., & Kraybill, D. S. (2017). Uninsured Health Shocks and Agricultural Productivity among Rural Households: The Mitigating Role of Micro-credit. The Journal of Development Studies, 53(12), 2050–2066. [CrossRef]

- Lagakos, D. (2020). Urban-Rural Gaps in the Developing World: Does Internal Migration Offer Opportunities? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), 174–192. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26923546.

- Lin, Wang, W., Gan, C., & Nguyen, Q. T. T. (2019). Credit constraints on farm household welfare in rural China: Evidence from Fujian Province. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 11(11), 3221. [CrossRef]

- Liu. (2016). Insuring against health shocks: Health insurance and household choices. Journal of Health Economics, 46, 16–32. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S., Palmer, M., Mont, D., & Groce, N. (2016). Can Households Cope with Health Shocks in Vietnam?. Health economics, 25(7), 888–907. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3196. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Bundervoet, T., & Nuru, M. (2020). Rural Roads, Poverty, and Resilience: Evidence from Ethiopia. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(10), 1838–1855. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura. (2022). Analysis of the spatial allocation of resources for a sustainable rural economy: A wide-areal coordination approach. The Annals of Regional Science. [CrossRef]

- Tonch, & Sohn, W. (2022). The impact of informal credit on household welfare: evidence from rural Ethiopia. Applied Economics Letters, 29(1), 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A., & Lindelow, M. (2014). Are health shocks different? Evidence from a multishock survey in Laos. Health economics, 23(6), 706–718. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2944. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).