Submitted:

08 August 2023

Posted:

09 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

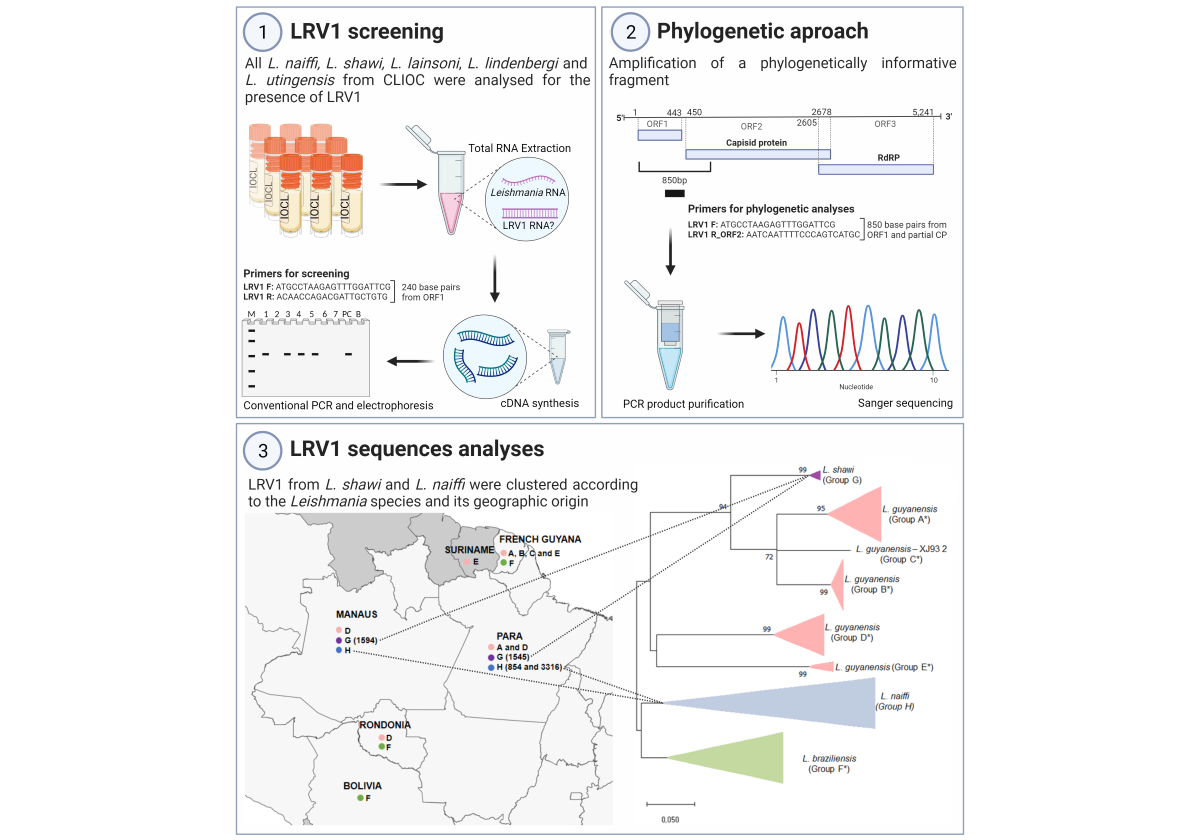

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Leishmania Culture

2.2. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

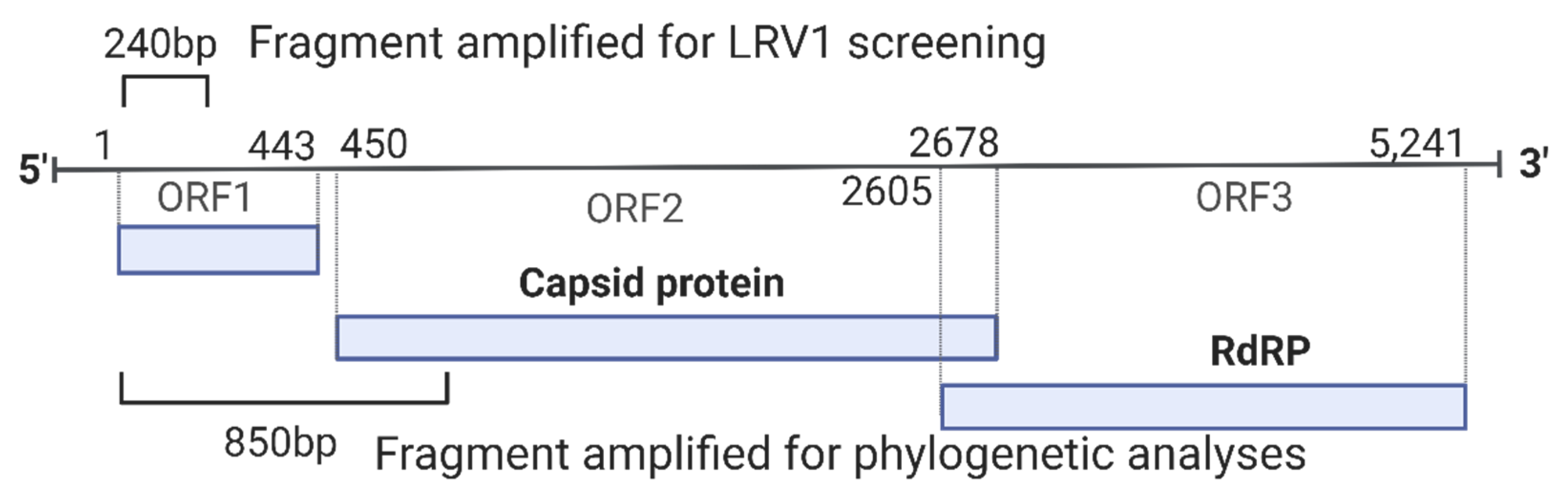

2.3. LRV1 Detection

2.4. Sequencing

2.5. Analyses of LRV1 Sequences

3. Results

3.1. LRV1 Was Not Detected in all L. (Viannia) Species Analyzed, but Was Frequent in L. naiffi Strains

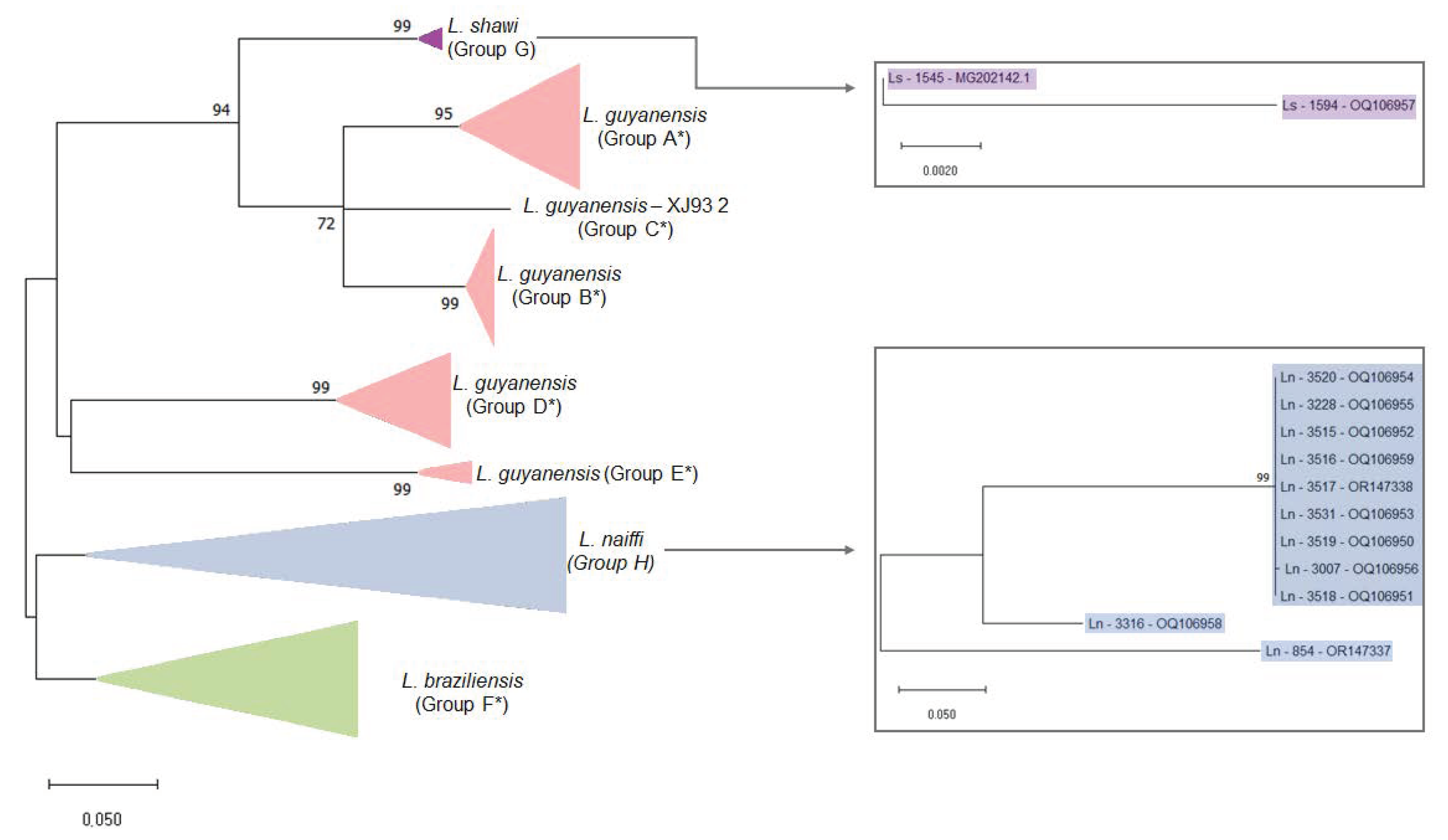

3.2. Variability of LRV1 Diversity across Leishmania Host Species

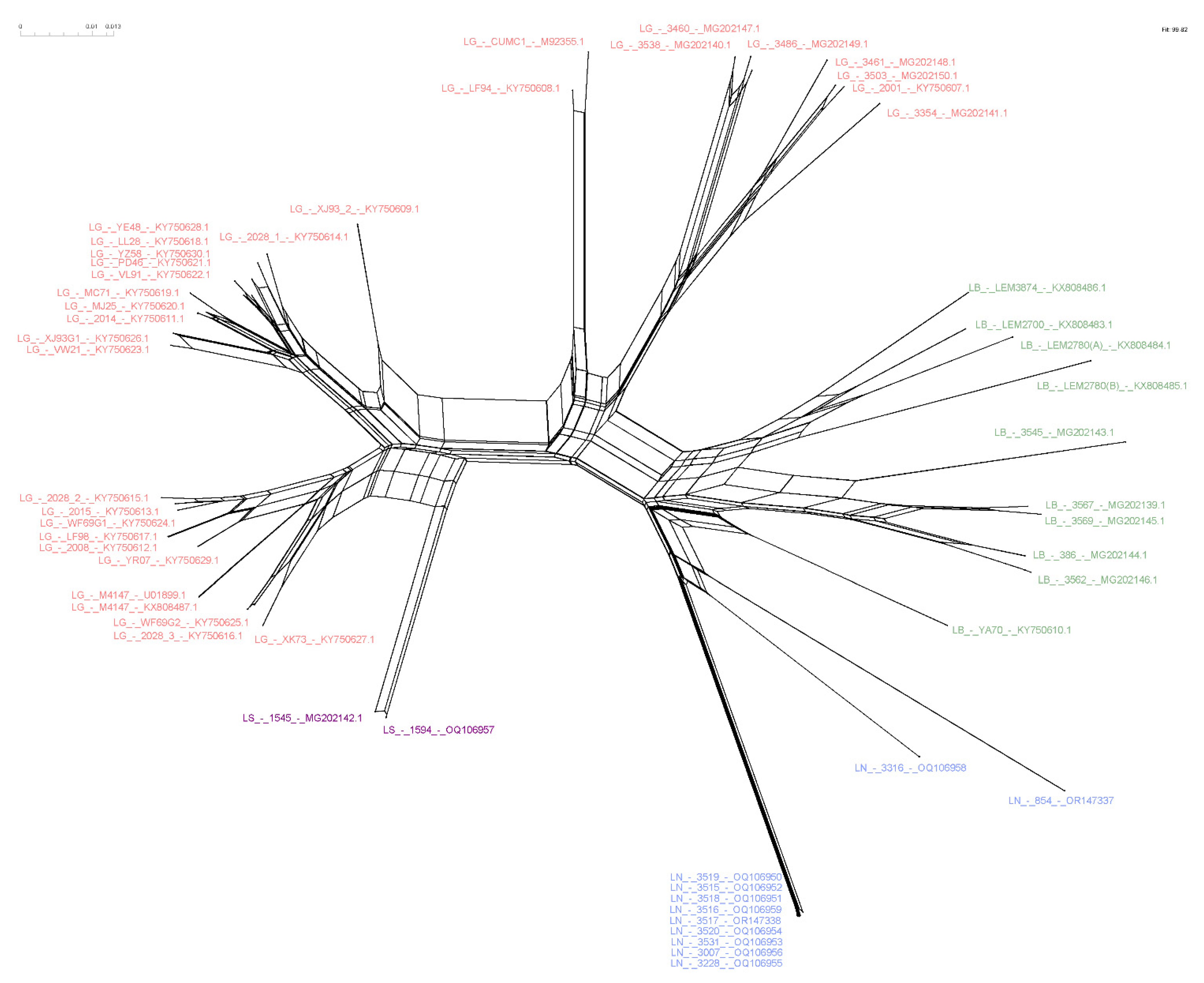

3.3. Higher Similarity Is Observed for LRV1 Sequences among Closely Related Leishmania Species

3.4. Host-Specificity Is Clear Observed in the LRV1-L. (Viannia) Species Relationship

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Control of the Leishmaniases. 2010.

- OPAS, O. Situação Epidemiológica Leishmaniose Cutânea e Mucosa; 2021.

- Zamora, M.; Stuart, K.; Salinas, G.; Saravia, N. Leishmania RNA Viruses in Leishmania of the Viannia Subgenus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996, 54, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantanhêde, L.M.; da Silva Júnior, C.F.; Ito, M.M.; Felipin, K.P.; Nicolete, R.; Salcedo, J.M.V.; Porrozzi, R.; Cupolillo, E.; Ferreira, R. de G.M. Further Evidence of an Association between the Presence of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 and the Mucosal Manifestations in Tegumentary Leishmaniasis Patients. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0004079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasawmy, R.; Menezes, E.; Magalhães, A.; Oliveira, J.; Castellucci, L.; Almeida, R.; Rosa, M.E.A.; Guimarães, L.H.; Lessa, M.; Noronha, E.; et al. The -2518bp Promoter Polymorphism at CCL2/MCP1 Influences Susceptibility to Mucosal but Not Localized Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Brazil. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2010, 10, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellucci, L.; Jamieson, S.E.; Miller, E.N.; De Almeida, L.F.; Oliveira, J.; Magalhães, A.; Guimarães, L.H.; Lessa, M.; Lago, E.; De Jesus, A.R.; et al. FLI1 Polymorphism Affects Susceptibility to Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Brazil. Genes Immun 2011, 12, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.T.; Lainson, R.; Corbett, C.E.P. Clinical and Immunopathological Spectrum of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with Special Reference to the Disease in Amazonian Brazil - A Review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2004, 99, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvar, J.; Croft, S.; Olliaro, P. Chemotherapy in the Treatment and Control of Leishmaniasis. Adv Parasitol 2006, 61, 223–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, A.; Ronet, C.; Prevel, F.; Ruzzante, G.; Fuertes-Marraco, S.; Schutz, F.; Zangger, H.; Revaz-Breton, M.; Lye, L.-F.; Hickerson, S.M.; et al. Leishmania RNA Virus Controls the Severity of Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis. Science (1979) 2011, 331, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, M.A.; Ronet, C.; Zangger, H.; Beverley, S.M.; Fasel, N. Leishmania RNA Virus: When the Host Pays the Toll. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2012, 2, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, G.; Phukan, A.C.; Hussain, M.; Lal, V.; Modi, M.; Goyal, M.K.; Sehgal, R. Virion Structure of Leishmania RNA Virus 1. J Neurol Sci 2019, 116544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Castiglioni, P.; Hartley, M.A.; Eren, R.O.; Prével, F.; Desponds, C.; Utzschneider, D.T.; Zehn, D.; Cusi, M.G.; Kuhlmann, F.M.; et al. Type I Interferons Induced by Endogenous or Exogenous Viral Infections Promote Metastasis and Relapse of Leishmaniasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 4987–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.V.H.; Lima-Junior, D.S.; da Silva, M.V.G.; Dilucca, M.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Horta, C. V.; Silva, A.L.N.; da Silva, P.F.; Frantz, F.G.; Lorenzon, L.B.; et al. Leishmania RNA Virus Exacerbates Leishmaniasis by Subverting Innate Immunity via TLR3-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourreau, E.; Ginouves, M.; Prévot, G.; Hartley, M.-A.; Gangneux, J.-P.; Robert-Gangneux, F.; Dufour, J.; Marie, D. Sainte; Bertolotti, A.; Pratlong, F.; et al. Leishmania-RNA Virus Presence in L. Guyanensis Parasites Increases the Risk of First-Line Treatment Failure and Symptomatic Relapse. J Infect Dis 2015, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira-Gonçalves, R.; Fagundes-Silva, G.A.; Heringer, J.F.; Fantinatti, M.; Da-Cruz, A.M.; Oliveira-Neto, M.P.; Guerra, J.A.O.; Gomes-Silva, A. First Report of Treatment Failure in a Patient with Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Infected by Leishmania (Viannia) Naiffi Carrying Leishmania RNA Virus: A Fortuitous Combination? Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2019, 52, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaui, V.; Lye, L.-F.; Akopyants, N.S.; Zimic, M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Garcia, L.; Maes, I.; De Doncker, S.; Dobson, D.E.; Arevalo, J.; et al. Association of the Endobiont Double-Stranded RNA Virus LRV1 With Treatment Failure for Human Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Braziliensis in Peru and Bolivia. J Infect Dis 2015, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirera, S.; Ginouves, M.; Donato, D.; Caballero, I.S.; Bouchier, C.; Lavergne, A.; Bourreau, E.; Mosnier, E.; Vantilcke, V.; Couppié, P.; et al. Unraveling the Genetic Diversity and Phylogeny of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 Strains of Infected Leishmania Isolates Circulating in French Guiana. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantanhêde, L.M.; Fernandes, F.G.; Ferreira, G.E.M.; Porrozzi, R.; Ferreira, R. de G.M.; Cupolillo, E. New Insights into the Genetic Diversity of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 and Its Species-Specific Relationship with Leishmania Parasites. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0198727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, K.; De León, S.S.; Pineda, V.; Samudio, F.; Capitan-Barrios, Z.; Suarez, J.A.; Weeden, A.; Ortiz, B.; Rios, M.; Moreno, B.; et al. Detection of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 in Leishmania (Viannia) Panamensis Isolates, Panama. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, R.; Mukkala, A.N.; Lau, R.; Valencia, B.M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Boggild, A.K. Virulence Factor RNA Transcript Expression in the Leishmania Viannia Subgenus: Influence of Species, Isolate Source, and Leishmania RNA Virus-1. Trop Med Health 2019, 47, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, R.; Grewal, J.; Lau, R.; Purssell, A.; Valencia, B.M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Boggild, A.K. Influence of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 on Proinflammatory Biomarker Expression in a Human Macrophage Model of American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis 2017, 216, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, B.M.; Lau, R.; Kariyawasam, R.; Jara, M.; Ramos, A.P.; Chantry, M.; Lana, J.T.; Boggild, A.K.; Llanos-Cuentas, A. Leishmania RNA Virus-1 Is Similarly Detected among Metastatic and Non-Metastatic Phenotypes in a Prospective Cohort of American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boité, M.C.; Mauricio, I.L.; Miles, M.A.; Cupolillo, E. New Insights on Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Population Genetics of Leishmania (Viannia) Parasites Based on Multilocus Sequence Analyses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagundes-Silva, G.A.; Sierra Romero, G.A.; Cupolillo, E.; Gadelha Yamashita, E.P.; Gomes-Silva, A.; De Oliveira Guerra, J.A.; Da-Cruz, A.M. Leishmania (Viannia) Naiffi: Rare Enough to Be Neglected? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainson, R.; Braga, R.R.; De Souza, A.A.; Pôvoa, M.M.; Ishikawa, E.A.; Silveira, F.T. Leishmania (Viannia) Shawi Sp. n., a Parasite of Monkeys, Sloths and Procyonids in Amazonian Brazil. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 1989, 64, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainson, R. The Neotropical Leishmania Species: A Brief Historical Review of Their Discovery, Ecology and Taxonomy. Rev Panamazonica Saude 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.P.; Nascimento, L.C.S.; Santos, F.S.; Takamatsu, J.L.C.; Sanchez, L.R.P.; Santos, W.S.; Garcez, L.M. First Report of an Asymptomatic Leishmania (Viannia) Shawi Infection Using a Nasal Swab in Amazon, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Graça, G.C.; Volpini, A.C.; Romero, G.A.S.; Neto, M.P. de O.; Hueb, M.; Porrozzi, R.; Boité, M.C.; Cupolillo, E. Development and Validation of PCR-Based Assays for Diagnosis of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Identification of the Parasite Species. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2012, 107, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analyses Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids. Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analyses across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huson, D.H.; Bryant, D. Application of Phylogenetic Networks in Evolutionary Studies. Mol Biol Evol 2006, 23, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettmann, E.A.; Shaik, J.S.; Zangger, H.; Lye, L.F.; Kuhlmann, F.M.; Akopyants, N.S.; Oschwald, D.M.; Owens, K.L.; Hickerson, S.M.; Ronet, C.; et al. Tilting the Balance between RNA Interference and Replication Eradicates Leishmania RNA Virus 1 and Mitigates the Inflammatory Response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 11998–12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, L.; Cusini, A.; Müller, N.; Zangger, H.; Hartley, M.A.; Desponds, C.; Castiglioni, P.; Dubach, P.; Ronet, C.; Beverley, S.M.; et al. Case Report: Severe Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus Patient Coinfected with Leishmania Braziliensis and Its Endosymbiotic Virus. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2016, 94, 840–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croft, S.L.; Molyneux, D.H. Studies on the Ultrastructure, Virus-like Particles and Infectivity of Leishmania Hertigi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1979, 73, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarr, P.I.; Aline, R.F.; Smiley, B.L.; Scholler, J.; Keithly, J.; Stuart, K. LR1: A Candidate RNA Virus of Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85, 9572–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, M.; Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Echevarria, J.; Roncal, N.; Cruz, M.; Tupayachi Muniz, M.; Lucas, C.; Wirth, D.F.; Scheffter, S.; Magill, A.J.; et al. Short Report: Detection of Leishmaniavirus in Human Biopsy Samples of Leishmaniasis from Peru. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1998, 58, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, G.; Zamora, M.; Stuart, K.; Saravia, N. Leishmania RNA Viruses in Leishmania of the Viannia Subgenus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996, 54, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata-somarribas, C.; Quesada-lópez, J.; Matamoros, M.F.; Cervantes-gómez, C. Raising the Suspicion of a Non-Autochthonous Infection : Identification of Leishmania Guyanensis from Costa Rica Exhibits a Leishmaniavirus Related to Brazilian North-East and French Guiana Viral Genotypes. 2022, 117, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couppié, P.; Nacher, M.; Demar, M.; Ginouvès, M.; Simon, S.; Prévot, G.; Bourreau, E.; Ronet, C.; Lacoste, V. Prevalence and Distribution of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 in Leishmania Parasites from French Guiana. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016, 94, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.M.; Catanhêde, L.M.; Katsuragawa, T.H.; da Silva Junior, C.F.; Camargo, L.M.A.; Mattos, R. de G.; Vilallobos-Salcedo, J.M. Correlation between Presence of Leishmania RNA Virus 1 and Clinical Characteristics of Nasal Mucosal Leishmaniosis. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2015, 81, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Ramos Pereira, L.; Maretti-Mira, A.C.; Rodrigues, K.M.; Lima, R.B.; de Oliveira-Neto, M.P.; Cupolillo, E.; Pirmez, C.; de Oliveira, M.P. Severity of Tegumentary Leishmaniasis Is Not Exclusively Associated with Leishmania RNA Virus 1 Infection in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2013, 108, 665–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, G.; Dooley, S. Phylogenetic Analyses of Leishmania RNA Virus and Leishmania Suggests Ancient Virus-Parasite Association. Nucleic Acids Res 1995, 23, 2300–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Chagas, B.D.; Pereira, T.M.; Cantanhêde, L.M.; da Silva, G.P.; Boité, M.C.; Pereira, L. de O.R.; Cupolillo, E. Interspecies and Intrastrain Interplay among Leishmania Spp. Parasites. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlmann, F.M.; Robinson, J.I.; Bluemling, G.R.; Ronet, C.; Fasel, N.; Beverley, S.M. Antiviral Screening Identifies Adenosine Analogs Targeting the Endogenous DsRNA Leishmania RNA Virus 1 (LRV1) Pathogenicity Factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantanhêde, L.M.; Cupolillo, E. Leishmania (Viannia) Naiffi Lainson & Shaw 1989. Parasit Vectors 2023, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Naiff, R.D.; Freitas, R.A.; Naiff, M.F.; Arias, J.R.; Barrett, T. V.; Momen, H.; Grimaldi Júnior, G. Epidemiological and Nosological Aspects of Leishmania Naiffi Lainson & Shaw, 1989. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1991, 86, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Der Snoek, E.M.; Lammers, A.M.; Kortbeek, L.M.; Roelfsema, J.H.; Bart, A.; Jaspers, C.A.J.J. Spontaneous Cure of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Due to Leishmania Naiffi in Two Dutch Infantry Soldiers. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009, 34, 889–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhls, K.; Cupolillo, E.; Silva, S.O.; Schweynoch, C.; Côrtes Boité, M.; Mello, M.N.; Mauricio, I.; Miles, M.; Wirth, T.; Schönian, G. Population Structure and Evidence for Both Clonality and Recombination among Brazilian Strains of the Subgenus Leishmania (Viannia). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013, 7, e2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantanhêde, L.M.; Mata-Somarribas, C.; Chourabi, K.; Pereira da Silva, G.; Dias Das Chagas, B.; de Oliveira, R. Pereira, L.; Côrtes Boité, M.; Cupolillo, E. The Maze Pathway of Coevolution: A Critical Review over the Leishmania and Its Endosymbiotic History. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, S.; Maes, I.; Sanders, M.; Lye, L.-F.; Arevalo, J.; Garcia, L.; Lemey, P.; Beverley, S.M.; Cotton, J.A.; Dujardin, J.-C.; et al. Parasite Hybridization Promotes Spreading of Endosymbiotic Viruses. [CrossRef]

- Tojal da Silva, A.C.; Cupolillo, E.; Volpini, A.C.; Almeida, R.; Sierra Romero, G.A. Species Diversity Causing Human Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Rio Branco, State of Acre, Brazil. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2006, 11, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Leishmania Strain ID (IOCL) | Parasite Species | Leishmania International Code | Geographic Origin (City, State) | Sequence Length | GenBank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 854 | L. naiffi | ISQU/BR/1985/IM2264 | Cachoeira Porteira, Pará | 759 | OR147337 |

| 3007 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2003/IRCF | Manaus, Amazonas | 701 | OQ106956 |

| 3228 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2010/MS | Manaus, Amazonas | 699 | OQ106955 |

| 3316 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2011/58-AMS | Mojuí dos Campos, Pará | 706 | OQ106958 |

| 3515 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/49UAS | Manaus, Amazonas | 709 | OQ106952 |

| 3516 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/63DDL | Manaus, Amazonas | 799 | OQ106959 |

| 3517 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/65HCC | Manaus, Amazonas | 710 | OR147338 |

| 3518 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/66CPS | Manaus, Amazonas | 679 | OQ106951 |

| 3519 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/51FRS | Manaus, Amazonas | 660 | OQ106950 |

| 3520 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/62FJFM | Manaus, Amazonas | 632 | OQ106954 |

| 3531 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2013/56EGP | Manaus, Amazonas | 708 | OQ106953 |

| 991 | L. naiffi | MDAS/BR/1987/IM3307 | São Félix do Xingu, Pará | - | --- |

| 992 | L. naiffi | MDAS/BR/1987/IM3280 | São Félix do Xingu, Pará | - | --- |

| 993 | L. naiffi | MDAS/BR/1987/IM3281 | São Félix do Xingu, Pará | - | --- |

| 1123 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/1986/IM2736 | Manaus, Amazonas | - | --- |

| 1365 | L. naiffi | MDAS/BR/1979/M5533 | Almeirim, Pará | - | --- |

| 3310 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2011/S50 | Santarém, Pará | - | --- |

| 3541 | L. naiffi | MHOM/BR/2014/61AAM | Manaus, Amazonas | - | --- |

| 1594 | L. shawi | MHOM/BR/1990/IM2842 | Manaus, Amazonas | 781 | OQ106957 |

| 1067 | L. shawi | IWHI/BR/1985/IM2324 | Tucuruí, Pará | - | --- |

| 1068 | L. shawi | IWHI/BR/1985/IM2326 | Tucuruí, Pará | - | --- |

| 3481 | L. shawi | MHOM/BR/2013/18 | Manaus, Amazonas | - | --- |

| 1023 | L. lainsoni | MHOM/BR/1981/M6426 | Benevides, Pará | - | --- |

| 1266 | L. lainsoni | MCUN/BR/1983/IM1721 | Tucuruí, Pará | - | --- |

| 2497 | L. lainsoni | MHOM/BR/2002/NMT-RBO 027P | Rio Branco, Acre | - | --- |

| 3398 | L. lainsoni | MHOM/BR/2012/AP60A | Porto Velho, Rondônia | - | --- |

| 2690 | L. lindenbergi | MHOM/BR/1966/M15733 | Belém, Pará | - | --- |

| 3645 | L. lindenbergi | MHOM/BR/2015/RO514 | Porto Velho, Rondônia | - | --- |

| 3746 | L. lindenbergi | MHOM/BR/2014/RO285 | Porto Velho, Rondônia | - | --- |

| 2689 | L. utingensis | ITUB/BR/1977/M4964 | Belém, Pará | - | --- |

| L. guyanensis | L. braziliensis | L. naiffi | L. shawi | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of differences | 448.96 | 295.15 | 31.75 | 7 |

| Tamura-3-parameter model | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| L. naiffi | L. shawi | L. guyanensis | L. braziliensis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. naiffi | - | 109 | 109 | 100 |

| L. shawi | 0.208 | - | 88 | 114 |

| L. guyanensis | 0.214 | 0.147 | - | 550 |

| L. braziliensis | 0.190 | 0.204 | 0.260 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).