Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic that started in March 2020 represented a major challenge in the teaching of anatomy in universities around the world, which required a rapid transition from a traditional face-to-face teaching model to digital platforms, representing a great challenge because although there was a record of its effectiveness, most teachers had no previous training in its use [

1,

2]. Cadaveric dissection has been the preferred method of teaching anatomy throughout history because students have a better perspective of the three-dimensionality of the structures of the human body, as well as the possible anatomical variants [

3]. Due to the restrictions that were imposed during the pandemic, medical schools all over the world were forced to reduce their dissection practice hours to almost zero [

4]and to re-invent the course on digital platforms with the available resources and the creation of new ones, several articles on the new and restructured teaching methods applied during the pandemic compared to those used previously were analyzed with the aim of comparing the results obtained based on the results obtained by the students and the preference of the students [

5,

6] Despite the new trend of online teaching, anatomy continues to be a subject of which cadaveric dissection is essential for the understanding of three-dimensionality, not to mention that it continues to be the preferred method for most students [

7,

8].

Material and Methods

A systematic literature review a was carried out by means of a systematized search, following the recommendations stipulated in the PRISMA statement. Inclusion criteria were original articles with analytical cross-sectional design, randomized and quasi-randomized clinical trials. Descriptive articles, as well as letters to the editor and registries without published results were excluded. Date filters were used to identify pre- and post-pandemic teaching strategies to evaluate change.

The search was carried out in PubMed, Google Scholar, OvidMD and CENTRAL. Search strategies included the terms Decs and Mesh in relation to the PICO question and used Boolean “AND” and “OR”.

The results of the searches were processed as individual files, using the digital platform Rayyan digital platform was used to select articles that would subsequently be assessed for methodological quality, quality of evidence and risk of bias to determine their inclusion or exclusion from the review. Subsequently, a selection was made of the articles that would be considered for use as part of the introduction to the review [

9].

The extraction of qualitative data from the included studies was carried out using an Excel spreadsheet developed in-house.

Data extraction was performed by two of the authors, 1 author (JQS) summarized all the evidence of the extracted data and presented them in a summary of findings table. These tables are included in the supplementary material.

Quality of Evidence

Quality was assessed using the OPMER tool, which scores methodological quality, consists of 5 items, with a maximum total score of 20 and a minimum of 0.Similarly, the quality of evidence was assessed using the evaluation checklist provided by the Johana Briggs Institute (JBI), which consists of 13 evaluation items, which are assessed according to presence, absence, uncertainty and non-applicability, and then each item is quantified and the scores are summarized. All articles with a score higher than 15 on the OPMER scale and with more than 10 items completed according to the JBI rubric were included in the systematic review [

10].

Results

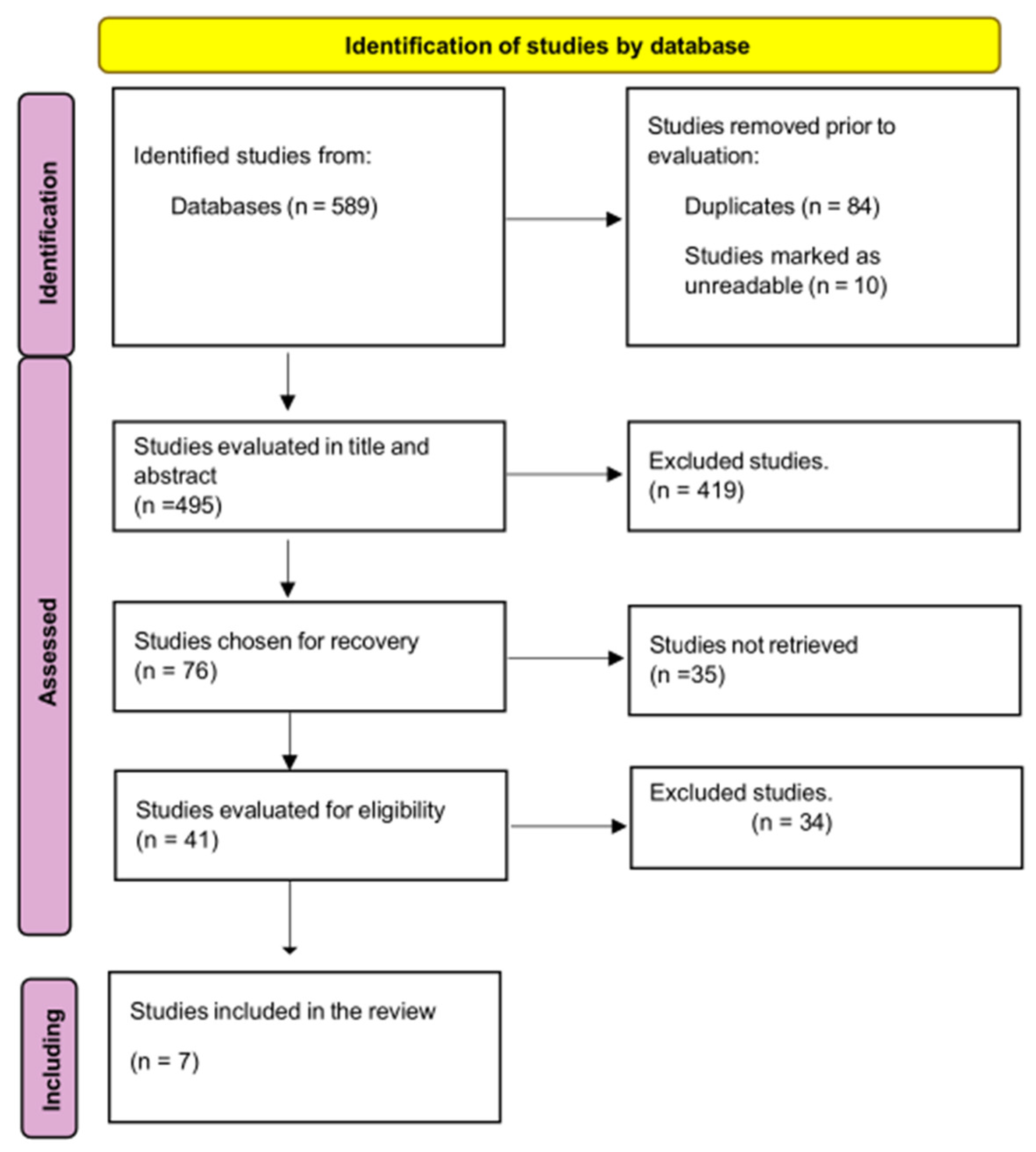

A total of 589 articles were retrieved, of which 84 were eliminated as duplicates and 10 were marked as illegible. A total of 495 studies were assessed in title and abstract so 419 were excluded after date filters considering 2 years as pre-pandemic margin and post-pandemic studies. 76 studies were eligible for retrieval and 41 studies were assessed for eligibility. A total of 34 studies were excluded due to low JBI tool scores, including a total of 7 studies within the review (

Figure 1).

Methodologic Analysis of the Studies

In general, the studies retrieved, including those that were not selected for inclusion in this systematic review, lack a certain degree of methodological quality and quality of evidence. Although most of them presented favorable statistical results with their respective hypotheses, the design and control of confounding variables did not favor the quality of the results.

The statistical methods used to control for confounding variables such as regression analyses were ignored, as well as the different distribution analyses and assumption tests. The most relevant characteristic was the inclusion of statistical methods that increased the risk of presenting type 1 error, so that the results can be represented as overestimates of the interventions performed.

In turn, the included studies present characteristics that strengthen part of the quality of the measurement of the variables, such as statistical tests to verify the internal validity of the evaluation tools, design of the same based on previously published references, as well as adequate management of the data and of the participants, since as a general view there were few losses in the studies.

The evaluation methods of the new modality interventions was conducted mostly based on historical records with groups of participants prior to the event of interest (COVID-19 pandemic), so the interpretation could be subject to bias. However, because the pandemic was an unexpected event, the presence of this type of bias is understandable since it is not possible to perform it through the methodological design.

Summary of Results

Cadaveric dissection continues to be the ideal method for teaching anatomy in medical schools, during the pandemic various teaching strategies were implemented to achieve the highest academic achievement despite the limitations that this meant, there was already a history of online teaching however it was a challenge as many teachers did not have the experience of the resources available, the lack of interest on the part of the students and the technical difficulties that arose.

After two years of effort and various techniques implemented, it was achieved that in the last course the students achieved a better satisfaction with the course, however there was no improvement in the level of knowledge of the students and the lack of understanding at a three-dimensional level of anatomy, therefore, it is essential to resume dissection in person as soon as possible, as well as demonstrating a greater understanding on the part of the students, greater self-confidence is achieved. It is a fact that technology and the available means must continue to be used and complement traditional dissection, which cannot be replaced but must be complemented to improve it.

Several authors describe the use of ONALs (Interactive online anatomy labs) online dissection laboratories as a novel teaching model in which the objective was to make the most similar to the traditional way of teaching through interaction between the students and the teacher to ensure attention and that the learning objectives were achieved, it was based on 3 different modules and at the end of the course a survey was conducted on a voluntary basis in which it was concluded that face to face teaching cannot be replaced however this can be a useful tool to complement learning once it is possible to return to the traditional way [

1].

The COVID 19 pandemic meant a great change in medical education, specifically in the teaching of anatomy, as cadaveric dissection has been the mainstay of medical education throughout history, so the pandemic has been a great challenge for teachers and students, and voluntary donation of cadavers was the way in which medical schools obtained them for study. However, there is now great concern about the safety and origin of the cadavers, their cause of death and whether they were infected by SARS-CoV-2 and whether this could represent a risk of infection for those who handle them. Regulations must be implemented to guarantee safety and teaching can resume as soon as possible as before, as well as being complemented by the technological tools available today [

3,

5].

Medical education witnessed unprecedented change due to the 2019 coronavirus pandemic, but it provided an opportunity to implement new strategies and improve existing ones. Near-peer teaching (NPT) is a familiar form of teaching in which higher grade students are charged with supervising the learning of lower grade students [

11].

Kelly M et al, 2020 [

1] performed a study aimed to evaluate and develop online anatomy lab sessions that sought to preserve the benefits of the dissection experience for first-year medical students based on a form of active videography that emulates the eye movement patterns that occur during the visual identification process. The online labs were favorably accepted by students and led to an improvement in their practical exams, leading to the conclusion that such video-based lab sessions can provide a viable replacement when face-to-face dissections are not available.

While Mitchell L. et al, 2021 [

11] Anatomy is a three-dimensional subject that requires an understanding of the relationships between structures, which can be difficult to achieve on an online-only platform, NPT has demonstrated over the years of implementation favorable feedback from students therefore the aim of this study was to validate online NPT as a learning strategy through online sessions that were led by two second year medical students and by conducting pre-delivered questions at the end of each session with rationale for their responses, the results suggest that this method of teaching anatomy online is comparable to the previous face-to-face format.

Ioannis Antonopoulus et al. 2022 [

5] examined pre-recorded videos of the tutor performing cadaver dissection and interacting synchronously with the students through 3 different anatomical sections with different number of sessions including the possibility for the tutor to pause the video and answer students' questions as well as reaffirming critical points of the dissection and at the end asking questions to ensure understanding of the learning objectives of each session. The labs were well accepted by the students because of the interaction between student and tutor, however they agreed that face-to-face dissection will continue to be the mainstay of teaching.

Veronica Papa and Elena Varotto 2021 [

7] declares that human anatomy has always occupied a central place in the teaching of medicine at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels through the dissection of cadaveric donors and thus managing to evaluate the three-dimensionality of the structures of the body. The pandemic caused an enormous challenge in the teaching of anatomy for both teachers and students, so in this study information was collected on the problems that this had caused, and it is agreed that it greatly affected the quality of teaching due to the lack of interaction between students and educators, in addition, the digital resources available were not totally adequate to replace cadaveric dissection. With the passage of time, better resources were created, so it was concluded that the application of these resources should be considered without abandoning the old practices to ensure that students acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for their medical training.

Despite the advantages offered by virtual dissection, it does not compare with the three-dimensional understanding that cadaveric dissection offers, and the skills obtained by students in learning to handle various materials in the laboratory, as this method cannot be replaced, but we can complement it with the help of technology and achieve a better understanding of anatomy as O.A. Onigbinde 2020 [

4] declares.

O.A. Onigbinde [

12] says that the impact of the covid 19 pandemic led medical schools around the world to reduce their dissection practice hours to almost zero, the study aimed to highlight the importance of resuming this practice as it is the mainstay of anatomy teaching as well as the one that provides the greatest understanding of it and the achievement of greater motor skills compared to virtual dissection, It is therefore important to take measures once the pandemic is over to guarantee safety in the handling of cadavers, the material to be used, the proper handling of the chemicals used, and the safety of the people exposed to these dissections.

Student feedback provides a particularly useful starting point for further development and refinement of curricula to make e-learning work well for students.

Discussion

Anatomical education lays the foundations for safe, efficient medical practice and given the great importance of its teaching the pandemic caused by COVID-19 was a great challenge to achieve the essential learning objectives and face-to-face cadaveric dissection has been the best way to achieve them [

3]. Despite the enormous amount of digital resources that currently exist and those that have been developed as a solution to this pandemic, the interaction achieved in the traditional way cannot be replaced. Good student participation was achieved in the methods reviewed, such as the laboratories created and the online peer education, obtaining similar results in the evaluations presented at the end of the modules, making them a good tool for complementing the teaching [

11,

5]. Now that most medical schools have returned to a face-to-face mode of traditional cadaveric dissection, these methods should be added due to their good results and acceptance, so they can be taken as a starting point for the future development of curricula and to achieve a better understanding of human anatomy [

3,

7].

Conclusions

The current teaching of anatomy continues to be uncertain, because although the majority of students have returned to traditional teaching by means of cadaveric dissection, what was learned during the pandemic should not be discarded, nor should the resources developed and those that were restructured to combat the difficulties presented, it was found that the face-to-face mode could not be replaced by an online modality due to the interaction between teacher and student that is achieved, However, this must be complemented with all the tools acquired during these years and even plan a restructuring of the course in which, with the use of both modalities, the necessary learning objectives are achieved and a positive educational change towards the future is achieved.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Harrell, K.M.; McGinn, M.J.; Edwards, C.D.; Warren Foster, K.; Meredith, M.A. Crashing from cadaver to computer: Covid-driven crisis-mode pedagogy spawns active online substitute for teaching gross anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2021, 14, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böckers, A.; Claassen, H.; Haastert-Talini, K.; Westermann, J. Teaching anatomy under COVID-19 conditions at German universities: Recommendations of the teaching commission of the anatomical society. Ann Anat. Anat. Anz. 2021, 234, 151669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulte, H.; Schmiedl, A.; Mühlfeld, C.; Knudsen, L. Teaching gross anatomy during the Covid-19 pandemic: Effects on medical students' gain of knowledge, confidence levels and pandemic- related concerns. Ann Anat. Anat. Anz. 2022, 244, 151986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onigbinde, O.A.; Chia, T.; Oyeniran, O.I.; Ajagbe, A.O. The place of cadaveric dissection in post- COVID-19 anatomy education. Morphologie 2021, 105, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulos I, Pechlivanidou E, Piagkou M, Panagouli E, Chrysikos D, Drosos E; et al. Students' perspective on the interactive online anatomy labs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surg Radiol Anat., 2022, 44, 1193–1199. [CrossRef]

- Allsop S, Hollifield M, Huppler L, Baumgardt D, Ryan D, Van Eker M; et al. Using videoconferencing to deliver anatomy teaching to medical students on clinical placements. Transl. Res. Anat. 2020, 19, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, V.; Varotto, E.; Galli, M.; Vaccarezza, M.; Galassi, F.M. One year of anatomy teaching and learning in the outbreak: Has the Covid-19 pandemic marked the end of a century-old practice? A systematic review. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2022, 15, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsafi, Z.; Abbas, A.R.; Hassan, A.; Ali, M.A. The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Adaptations in medical education. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 64–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayyan—AI Powered Tool for Systematic Literature Reviews. 2021. Available online: https://www.rayyan.ai/ (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Mauricio Pierdant-Pérez, Andrés Castillo-Dimas, Ricardo Daniel Tirado-Aguilar. Como leer un artículo de investigación: En ciencias de la salud. 1st edition. Vol. 1. San Luis Potosí: UASLP; 2022. 94 p.

- Thom, M.L.; Kimble, B.A.; Qua, K.; Wish-Baratz, S. Is remote near-peer anatomy teaching an effective teaching strategy? Lessons learned from the transition to online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2021, 14, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onigbinde, O.A.; Ajagbe, A.O.; Oyeniran, O.I.; Chia, T. Post-COVID-19 pandemic: Standard operating procedures for gross anatomy laboratory in the new standard. Morphologie 2021, 105, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).