1. Introduction

Burnout syndrome develops as a consequence of chronic stress among employees, particularly those who perform high-risk jobs or care and protection jobs or jobs involving helping other people [

1]. Christiana Maslach defined it as “a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and a lowered sense of personal accomplishment (PA) that can be observed in people working with others in a certain specific manner” [

2]. EE is characterized by a sense of emotional overextension as a result of work; depersonalzation is characterized by emotional indifference and dehumanization of service recipients; diminished sense of personal accomplishment is characterized by a sense of professional stagnation, incapability, incompetence, and unfulfillment. DP refers to the development of an insensitive and cynical attitude toward people who are service recipients, a negative attitude toward work, and the loss of a sense of own identity.

A diminished sense of PA refers to a negative self-assessment of competences and accomplishments at a workplace, and the symptoms manifest as a lack of motivation to work, as well as a decline in self-esteem and general productivity [

3,

4].

The police job is, considered stressful, leading to poor physical and mental health outcomes over time, in which burnout is included [

5,

6]. In the United States of America (USA), the prevalence of burnout was explored in a sample of 13,000 police officers from across 89 police agencies, describing that 19% of the sample felt emotionally exhausted on a weekly basis, and 13% had severe levels of depersonalization [

7] describing that 19 % of the sample felt emotionally exhausted on a weekly basis and 13 % had severe levels of depersonalization. In Sweden [

8], in a sample of 856 patrolling police officers, 28 % reported high levels of emotional exhaustion and 56 % increased levels of depersonalization. In Spain, in a sample of 747 and in police officers and guards in prisons in Spain, the percentage of those with burnout was 43.6% [

9]. According to the results of Lastvikova et al. (2018), in the European Union (EU), about 8% of the German working population believe they suffer from burnout syndrome [

10]. In Costa Rica, the prevalence of total burnout was 44.4% [

11].

Private security refers to the security protection services that private security organizations provide to control crimes, protect lives and other assets, and maintain order at their employers’ facilities [

12]. The private security sector is a set of registered private companies specializing in providing commercial services to domestic and foreign clients regarding the protection of people, property, and objects in accordance with the law [

13]. Private security agencies started emerging in the late 20,

th century, achieving real expansion in the beginning of the 21 century. In most Western countries, private security agencies are responsible for ensuring public order and-protecting critical national infrastructures, such as banks, embassies, and airports. Private security officers also perform a variety of tasks that public police do not usually perform such as surveillance activities, information protection, and risk management [

14].

In developed countries with a long tradition of private security protection such as the USA, Great Britain, and France, these organizations have an important position within the system of national security [

15]. There are about 1.7 million employees in the private security sector in the European Union (EU) [

16],about 2 million in the USA [

17], and about 40,000 in the Republic of Serbia [

18].

Working in the private security sector is most similar to police work in most Western countries, whereby security employees have almost the same responsibilities and perform similar tasks [

13,

14]. The basic difference between state police officers and private security officers is reflected in the fact that police officers have legal power delegated by the state [

12,

13,

14]. On the other hand, private security employees do not have the status of authorized officers; although they have powers similar to police they apply them in protected areas and in specific circumstances. Private security sector employees participate less in the decision making regarding work organization; they have less training than police officers and are generally less valued by society. In many cases, private security officers receive inadequate training [

18].

The main characteristics of the professional private security sector in Central Serbia are as follows: the third largest group of people under arms with about 40,000 employees [

18]; employees have different levels of training and different levels of education; employees have low social and economic status. Employees in the professional private security sector are exposed to various risk factors that can cause stress for an individual. In a country such as Serbia, which has undergone economic, political, and social reforms, as well as military and police reforms, a somewhat different hierarchy is expected with regard to job stressors, compared to developed countries. It is impossible to remove all the workplace stressors within a private company, but it is necessary to identify the stressors in order to reduce exposure and prevent the occurrence and development of burnout syndrome [

18,

19].

A review investigating the risk factors for stress among police officers reported that officers who worked in big cities were more prone to higher levels of stress and post-traumatic stress disorder as they were more frequently exposed to violent and extreme situations [

20]. Burnout has serious professional and personal consequences, including lack of professionalism (often sick-leaves, reduced efficiency at work, lack of interest, and non-collegiality),problems in communication with close persons, divorces, losing friends, alienation, and aggressiveness [

20,

21],which has a negative impact on the employees`. Several studies have concluded that employees with higher levels of burnout are more likely to suffer from a variety of physical health problems such as musculoskeletal pain, gastric alterations, cardiovascular disorders, headaches, insomnia, and chronic fatigue, as well as increased vulnerability to infections [

22,

23,

24].

Maslach and Jackson (1981) explained that security officers and their families pay an emotional price for the officers’ occupational stress because they often take home the tension they suffer at work. Officers go home while experiencing feelings of anger, emotions, tension, and anxiety, and they are usually in complaining mode [

4].

The study objectives were to examine if burnout is prevalent in the security employees in the professional private security sector, and what socio-descriptive characteristics of employees might be associated with the appearance of the burnout. Additional objective was to evaluate the quality of life among security employees of the professional private security sector in Central Serbia.

2.1. Study Design

A multicenter cross-sectional study was performed. The study was conducted on a representative sample, the size of which was determined using

The study included security staff employed at private agencies in seven cities in Central Serbia. The representative sample size was 439, the study strength was 80%, and the type 1 error probability α was 0.05. The study included 353 questionnaires that were completely filled out. The response rate was 80%. The study was performed in the period from 3 March, to 30 April, 2019.

The study inclusion criteria were as follows: adults 18-65 years of age, citizens of the Republic of Serbia, and full-time employees, who were licensed to work in private security, had-finished the basic training for using weapons, and were working longer than 12 months. Exclusion criteria were as: staff in the process of obtaining the license, discontinuity at work longer than 1 year, long-term sick leaves or multiple workplace changes in the past 5 years, respondents recently exposed to major psychophysical trauma regardless of the professional environment (illness or death of a close person, divorce…etc.), and refusal to participate in the study.

The total score of the each respondent was obtained by summing up the matrix with a specific key for each of the three previously mentioned subscales, and the total degree of occupational burnout is represented by a comprehensive scale calculated based on a precise formula. High level of burnout at work is reflected in high scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales and low scores on the personal accomplishment subscale.

This means that high scores on the EE and DP scales contribute to the burnout syndrome, while high scores on the professional accomplishment scale diminishes it. A medium level of burnout is a reflection of mean scores on all three subscales. A low level of burnout at work is reflected in low scores on the EE and DP subscales and high scores on the PA subscale. The PA scale is relevant only if confirmed with the EE or DP scale.

2.1.1. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Questionnaire

This is an internationally accepted burnout measuring standard that measures three burnout subscales, and it is often used as a model for the evaluation of validity of other burnout risk assessment scales. We have used the questionnaire for staff employed at institutions who are in direct contact with people (Human Services Survey, MBI-HSS) with 22 variables [

26].

In the Republic of Serbia, licenses for the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) questionnaire and the evaluation key, as well as usage permission, were obtained directly from the current license owners-the SINAPSA EDITION Company (license No. 2/2018, dated 9 May-2018).

The managers of private security agencies provided written approval for the research. All respondents were informed in detail about the research, and they signed the consent forms to participate in the study.

MBI-HSS consists of 22 questions that are subsequently used in the calculation of three subscales measuring different occupational burnout aspects.

It is a self-administered questionnaire. Each question consists of a series of statements expressing the degree of agreement with the expressed statements, and the response categories are provided through a seven-point Likert scale:-(0-never, 1-once a year or less, 2-once a month or less, 3 a few times a month, 4--once a week, 5-a few times a week, 6-every day).

The total score of each respondent was obtained by summing the matrix with a specific key for each of the three previously mentioned subscales, and the total degree of occupational burnout was represented by a comprehensive scale calculated using a precise formula. A high level of burnout at work is reflected in high scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales and low scores on the personal accomplishment subscale. This means that high scores on the EE and DP scales contribute to burnout syndrome, while high scores on the professional accomplishment scale diminish it. A medium level of burnout is a reflection of mean scores on all three subscales. A low level of burnout at work is reflected in low scores on the EE and DP subscales and high scores on the PA subscale. The PA scale is relevant only if confirmed with the EE or DP scale.

2.1.2. Short Form 36 Health Survey- (SF-36)

SF-36 is the most commonly used general questionnaire that measures subjective health, i.e., the health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The questionnaire is a generic instrument for measuring health status and quality of life. It is standardized and very sensitive for assessing the overall impact of health on the quality of life. It consists of 36 questions covering a period of 4 weeks. It is designed to analyze self-ranking individual perception of health, functional status, and sense of wellbeing [

27]. The questions cover eight domains in the field of health: physical functioning, limitations due to physical health, body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, limitations due to emotional problems and mental health. When the total of each individual domain is calculated, the next step is calculating the Physical Health Composite Score (PHC) and Mental Health Composite Score (MHC), which are related to the quality of life.

The eight domains of this questionnaire were used to assess the category (dimension) of functional health and the sense of well-being; four for physical and four for mental status. Very important for measuring the physical health are the following dimensions: physical functioning, physical role, body pain, and general health. All individual scores and both composite scores can have values ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 is very poor quality of life and 100 is ideal quality of life resulting from good physical and mental health. Composite scores of physical and mental health are used to calculate the total quality of life (TQL) score. The scales of vitality and general health have good validity; and the questionnaire is used to compare different conditions and diseases, and it is considered the “gold standard” in assessing the quality of life related to health.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted in the SPSS-version 22 program package. We calculated means, odds ratios (ORs), and confidence intervals (CIs), and we performed variance analysis (ANOVA). (Repeated-measures ANOVA) was applied to test the statistical significance of changes in values of the indicators of quality of life. For the comparison of numerical characteristics, we used Student's t-test. The chi-squared test was used to compare frequencies between groups, or the Fisher test was used when the expected frequency was <5 in one of the cells. A univariate logistic regression analysis, followed by a multivariate one was used to assess the relationship between burnout and the characteristics of the respondents obtained from the questionnaires. Spearman correlation analysis was used to assess the association of descriptive characteristics with burnout syndrome, and Spearman ́s coefficient of rank correlation was calculated (r), too. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Descriptive Characteristics of the respondents

Of the total number of people contacted (439) a total of 353 respondents (330 male and 23 female) participated in the study. The response rate was 80%. Men represented 93.5% of all respondents, and they were significantly older than women: 44.09±11.44 vs. 36.91±7.92 years (F=8.752; p=0.003).

Overall, 224 (64.3%) respondents were married, about 1/3rd did not have children (33.7%), and more than half had completed high school (54.7%). A minority of the employees had a university degree (7.6%). There were 300 (78.00%) employees in service; about 22.7% held managerial positions, 288 (81.6%) worked in shifts, and most respondents, (as many as 277; 78.5%), worked 8-12 h a day. More than 60% responded are satisfied with the working conditions. Approximately one third (32.6%) is armed at work. The biggest number of the respondents (71.4%) had monthly revenue at the level of a minimum average salary.

3.2. Burnout in Security Employees in the Private Sector

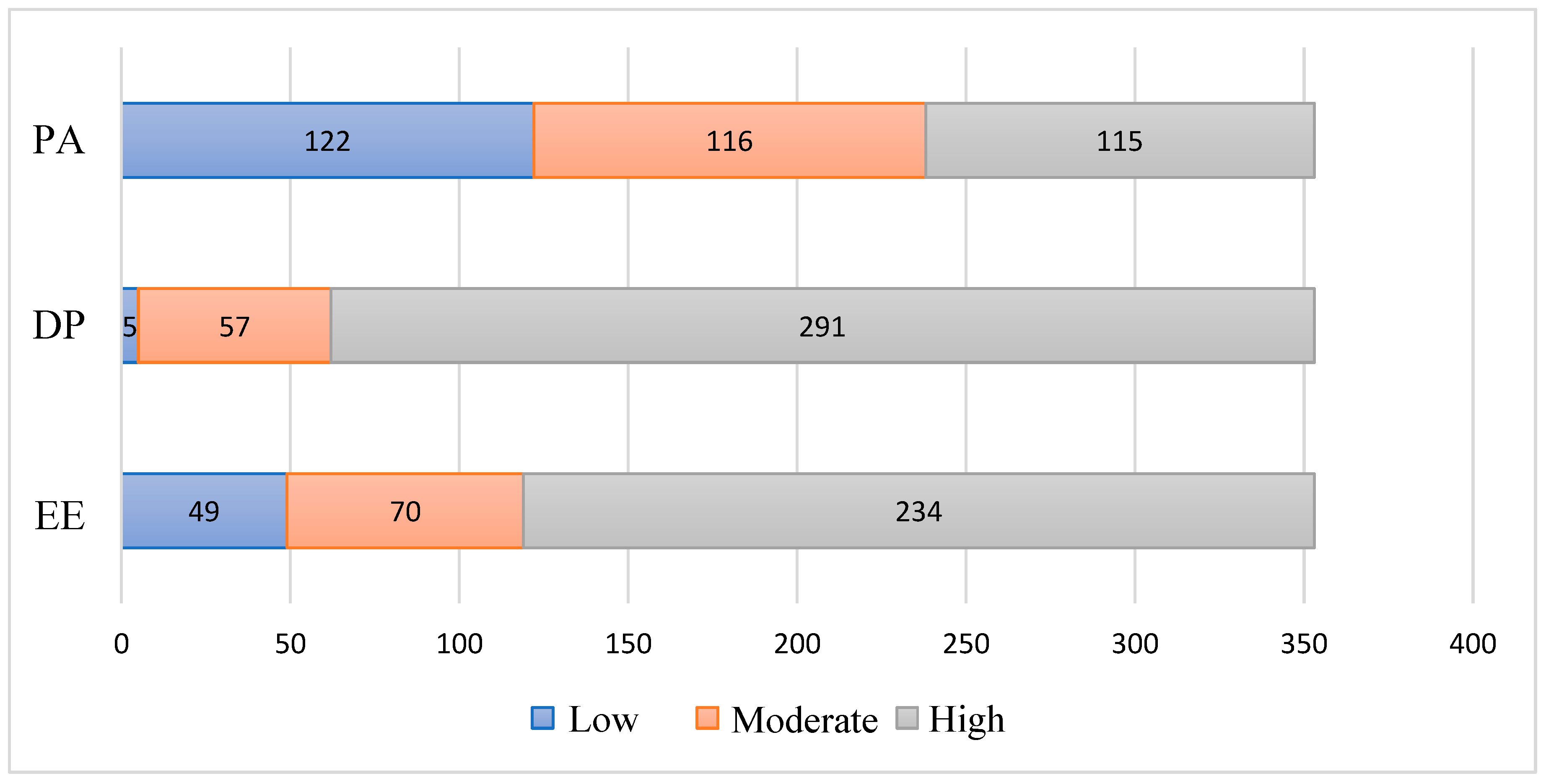

Figure 1 shows the values of subscales of burnout syndrome by severity – high, moderate, and low.

More than half of the employees (66.3%) had a high level of EE, 19.8% (n=70) had a moderate level and 13.9% (n=49) had a low level of EE. Cumulatively, high and moderate levels of EE were present in 86.1% of employees.

The largest number of employees, 82.4% (n=291), had a high level of DP. Moderate level of DP was present in 16.2% (n=57) and low level in 1.4% (n=5) of employees. Questions included in the PA subscale are inversely related to the previous two so that employees with medium and low values contribute to the burnout syndrome. Low PA was recorded in 34.5% (n=122), moderate in 32.9% (n=116) and high in 32.6% (n=115) of employees.

For each subscale of burnout (EE, DP, and PA) and for total burnout, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed, and the results are presented in

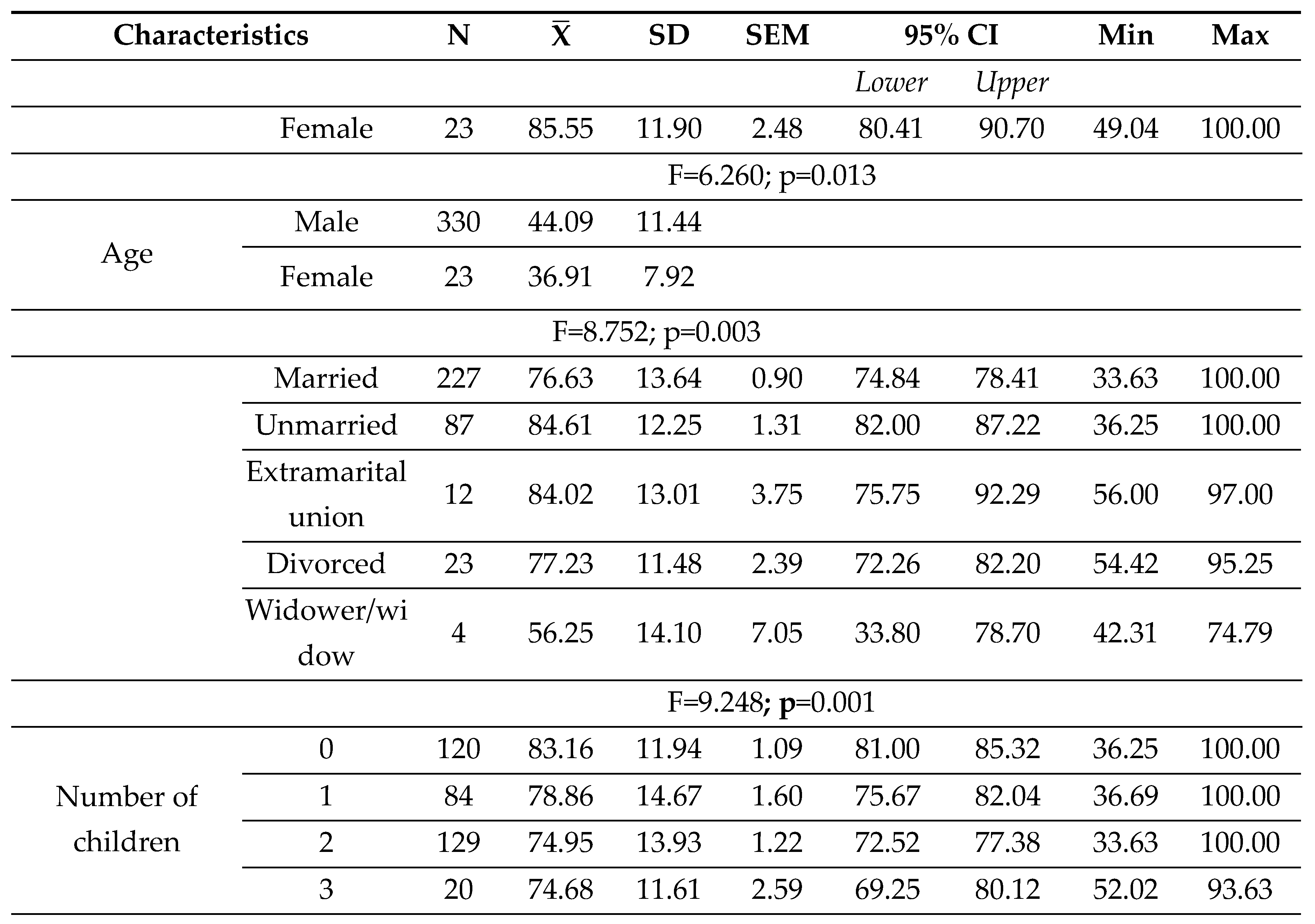

Table 1.

Table 1 shows the results of EE, DP, and PA subscales and for the total burnout, modeling with the application of multivariate logistic regression analysis in regard to the socio-descriptive characteristics as independent variables: (sex, age, marital union, number of children, education, and managerial position).

The independent variable ˝sex˝ was found to be significant at the p=0.10 level; its cross-ratio (i.e., the male category in relation to the female reference category) was 0.277, while its corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) for the cross-ratio was 0.098-0.780. On the basis, it was determined that employed men were 82% less likely to exhibit EE compared to employed women.

The independent variable “age˝ of the employees also showed a significant effect on a high degree of EE in the examined group (p<0.001). The chances of an employee having a high degree of EE increased with age, at a ratio of 0.962, (95% CI: 0.946-0.979). With each additional year of life, EE increased by 3.8%. The effect of dependent variables on the independent variable (i.e., level of depersonalization) was not determined.

The reference category was represented by high and moderate levels of PA. The sex of the respondents stood out as a significant variable in the dependent PA variable modeling. The cross-ratio of “male” in comparison to the reference category “female” amounted to 2.644, significant at the level of p= 0.10, while its corresponding 95% confidence interval for the cross-ratio was 0.879-7.954. The probability that male responders manifested burnout in the form of lowered PA was reduced by 164% in comparison to female respondents.

The respondents’ education also stood out as a significant variable in the dependent PA variable. The cross-ratio of “university” education in comparison to the reference category of “3 years of secondary school” amounted to 3.698,significane at the level of p=0.10, while its corresponding 95% CI for the cross-ratio amounted to 1.237–11.051. The probability that responders with university education manifested the burnout in the form of lowered PA was reduced by 269% in comparison to the respondents with 3-years of secondary school.

Table 2 shows the average scores of the basic eight domains of the SF-36 questionnaire. Physical functioning (PF) was the domain with the highest average value (93.68), while the average score for vitality (VT) was 62.15, and that for general health (GH) was 66.60.

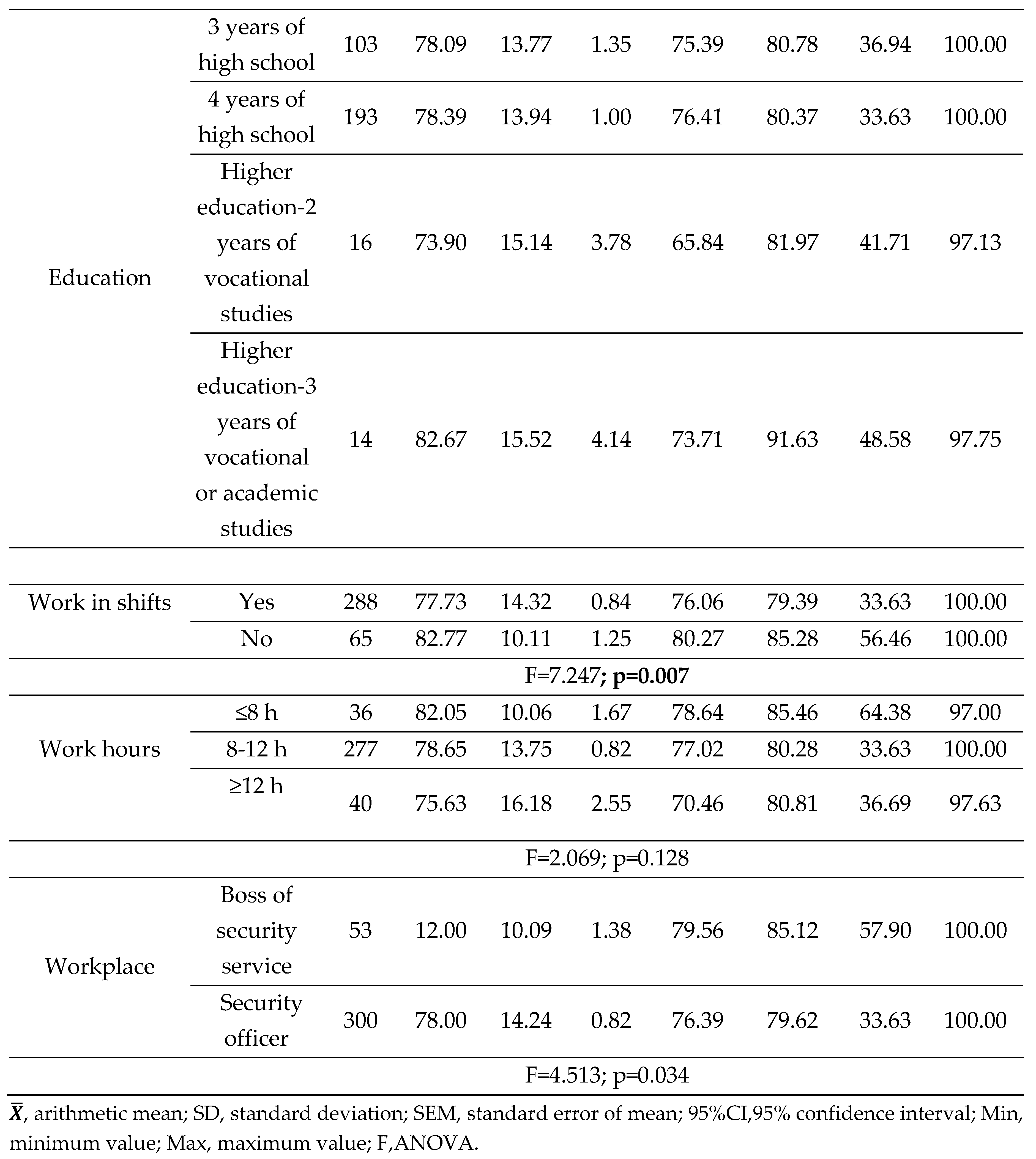

Table 3 shows a composite score of PHC in relation to the socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

Compared to men, a significantly higher PHC score was observed in women (p=0.011), as well as in unmarried participants (p=0.001). PHC score was significantly higher in employees without children (p=0.001), compared to employees with children. Employees working in shifts had significantly higher average values of PHC score (p=0.005). Working hours had no significant impact on the PHC score (p=0.147), whereas the managerial position had a significant impact on increasing PHC score (p=0.009).

Table 4 shows the composite MHC score in relation to the socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

There was no significant difference in the average MHC score in relation to the sex of employees (p=0.071). Widows/widowers had a significantly lower MHC score compared to employees with different marital status (p=0.001). Employees without children or with one child had a significantly higher MHC score compared to employees with two or three children (p=0.049). The level of education had no significant impact on the average MHC score (p=0.598). Work in shifts (p=0.070), working hours (p=0.171), and managerial position (p=0.355) had no significant impact on the average MHC score.

The mean total quality of life (TQL) score was 78.66±13.77. The mean composite score was 79.98±17.57 for PHC and 77.33±13.14 for MHC.

Table 5.

TQL score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

Table 5.

TQL score in relation to socio-descriptive characteristics of employees.

Compared to women, men had a significantly lower average score of total quality of life (p=0.013). Married employees had a significantly lower TQL score compared to those who were not married (p=0.001). Widowed employees had the statistically lowest TQL score. Employees without children or with one child had a significantly higher TQL score, compared to employees with two, three, or more children (p=0.001).

Education did not have a significant impact on the average TQL score (p=0.160). Shift work has a statistically significant impact on the reduction in average TQL score (p=0.007). Employees in managerial positions had a significantly higher TQL score compared to those who did not hold managerial positions (p=0.034).

4. Discussion

According to the presented results of our study, approximately one-third of responders had symptoms of burnout syndrome. In contrast to “total burnout”, a much higher number of employees developed a moderate or high level of burnout symptoms on individual subscales: EE (high 66.3%, moderate 19.8%); DP (high 82.4%, moderate 16.2%); PA (low 34.5%, moderate 32.9%).

According to Maslach theory, EE has the greatest prevalence in surveys, and this was not the case in our study. In our study DP had the higher prevalence. In the literature, working hours and satisfaction with a working conditions and career significantly predicted depersonalization. Participants who were dissatisfied with their career in medicine for example, were 22 times more likely to experience DP (OR = 22.28; 95% CI: 1.75– 283.278) than those who were satisfied. Those who neither agreed nor disagreed that they were satisfied with their career in medicine were 23 times more likely to show depersonalization (OR = 23.81; 95% CI: 4.89–115.86) compared to those who agreed that they were satisfied [

28].

There were significantly more men than women in the survey, and they were significantly older than women. Security work is considered a male occupation in many countries, and this is no different in Serbia; thus, the sex differences were expected. Results from a systematic review reported that women seem to suffer more from burnout than men [

29]. Our study show that female sex and older age were associated with a higher risk of total burnout and the development of EE. Some studies have shown that women suffer more from burnout than men [

25], while others have indicated that males report higher burnout scores [

28,

29,

33,

34,

35]. In our study, the male sex of the employees also stood out as a significant variable for the PA subscale. Our findings are compatible with published studies that demonstrate an increased risk of burnout among women [

25,

31,

35,

36,

40].

There have also been different results in the literature according to which men are protected from EE if they are in an emotional relationship, while women are at risk of developing EE if they have a family [

30,

31]. In one study, similar to ours, the EE subscale of burnout presented the highest score in participants [

29]. State police officers who were in an emotional relationship were more prone to EE but experienced higher PA, and there was no statistically significant difference between state police officers in the civil service who had children or not, with regard to the development of burnout [

32].

Employed women, due to their responsibilities toward their family and work, have difficulties in harmonizing professional and private obligations. In certain studies, women were found to be more prone to EE [

20,

21], while men were more susceptible to DP. We found a significant association of male sex, higher education, and managerial position with higher PA and a lower risk of total burnout. This subscale is inversely correlated with burnout. In our study, ≤10% of participants had a university degree. In a similar study, conducted with state police officers in Spain, there were almost twice as many employees with a university degree, compared to employees from our study. No significant relationships were found between educational level and burnout in this study [

29].

According to the findings of Ronen and Pines [

32], te Brake et al. [

33], and Maccaaro [

34], male sex, shift work, and a low score in relationships with superiors at the work-place were connected with a higher rate of burnout than females. According to results of similar studies, women have a greater tendency to utilize emotion focused coping a their manner of support, leading to greater work-family conflict [

35].

A systematic review of the determinants of burnout [

36] found a significant relationship between increasing age and increased risk of DP; on the other hand, there was also a greater sense of PA. The results of some studies point to an inverse relationship between age and burnout, such that people will experience lower levels of total burnout as their age increases [

8,

25,

40]. Our findings are compatible with published studies that demonstrated an increased risk of burnout with increased age. Results of a study performed on the professional military personnel of the Serbian Armed Forces [

41] showed that the highest level of burnout was measured on the subscales EE in military personnel aged 23–30 years of age (p< 0.05). De Solana reported that being younger contributed to increased burnout levels [

30].

In relation to marital status, employees who were unmarried seemed to be more exposed to burnout compared to those who lived with a partner in our study. However, such findings seem to be more appropriate in men, as, in the case of working women, it constitutes an additional risk factor, since working women are usually responsible for household chores, therefore, this may pose a difficulty in reconciling personal and professional life [

20,

21,

28]. No significant association with burnout was found [

10].

Having children is associated with lower PA [

30]. In a study by Brady et al. (2017), a higher number of children was correlated with a lower level of burnout [

31]. Our study only showed that employees without children or with one child had a significantly higher quality of life, compared to employees with two, three, or more children.

According to our results, burnout decreased with the increase in academic qualifications, which is consistent with the results from the literature [

29,

31,

40]. In EU countries, there are significantly more employees with higher education and university degrees [

8,

9,

20,

25] than in our country.

Fewer than one-third of our participants were obliged to carry a weapon at the workplace. Security officers are armed for the entire time at the workplace, after completing the obligatory training. According to Mastracci et al., use-of-force is a workplace stressor [

23]. According to our results, a managerial position and higher education were protective factors in relation to the development of burnout. A possible explanation could be the fact that managers are less exposed to direct contact with clients and potential attackers; moreover, they do not usually work in shifts and have shorter working hours. They also don ́t have an obligation to carry a weapon at the workplace. Educated individuals with more work experience have more self confidence in the performance of their duties; they show greater self-control in contact with various stressors and experience less emotional trauma [

30].

Burnout affects the quality of life (QOL) of employees. According to our findings, some socio-descriptive characteristics of employees significantly affected QOL. Male sex, marital union, two or more children, and direct contact with clients were significantly associated with a lower quality of life in security employees. Despite married employees having a low quality of life, in our study, widowed employees had the lowest quality of life. While shift work significantly decreased the total quality of life, managerial positions increased the quality of life of the employees. A literature review showed that shift and night work can have multiple negative influences on worker health [

42]. Correctional officers in Brazil showed the presence of both burnout and reduced quality of life, [

43]. De Moraes et al. (2019) presented that 19.2% of their total sample had high levels of burnout, and the same participants also exhibited reduced quality of life [

44].

The emphasis on burnout prevention by the state authorities and workers in the EU shows that burnout syndrome is a problem that confers an economic burden; in the context of worker effectivity and health, it has to be dealt with. With such a perspective, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) supports the prevention of occupational stress-related disorders throught the campaign: ˝ Healthy workplaces manage stress˝ [

45].

The possibility of developing job burnout among employees in the professional private security sector in the Central Serbia can be seen in a broader context context by examining general values, political and economic opportunities, and instability in the region. Bearing in mind the specifics of the job, an examination of the socio-descriptive characteristics of candidates before employment is necessary, which would enable the identification of persons at higher risk. In this way, a better selection of candidates for security jobs can be established, and the risk of burnout can be prevented or reduced, while mitigating the negative effects on employee ́s quality of life. Monitoring employee job satisfaction, continuously improving work organization, continuously educating-employees in security work, and bringing awareness to burnout symptoms can enable timely treatment, rehabilitation, temporary job changes, or, permanent job changes, with the aim of preserving the health and life of employees.

As a strength, this is the first study of burnout in professional private security employees in Central Serbia. The employees were interested in this topic and willingly participated in the study. According to the results obtained in our study, the following factors bother employees the most: working in shifts, working more than 8–12 h a day, and minimum wage.

There were several limitations of our study. Only cross-sectional data were used; hence, no causal relationships could be identified. The quality of life was self-assessed, which may have led to desirability bias.

Practical applications of the findings of our study in the daily work of security employees can be implemented immediately after its completion. All employees with a high score of total burnout can be referred to a psychologist and, if necessary, to a psychiatrist. An occupational medicine specialist can be included in the consultation with employees. Employees may change workplace, whether temporary, but if necessary, or permanent, according to a psychologist ́s advice. Security officers whose biggest problem is working in shifts can be transferred to the workplace only for a daily shift and working hours can also be reduce in some employees.

Author Contributions

N.K.R.— investigation, methodology, writing-original drift, D.R.V.— investigation, conceptualization, methodology M.R.M. —conceptualization, methodology, supervision, Lj.K.M. — conceptualization, supervision, V.S.J. data curation, formal analysis, methodology, B.N.S.- data curation, investigation, N.S.M.-formal analysis, study design, supervision, C.M.V.— data curation, investigation, M.Z.M.E. — data curation, investigation, software, G.D.S. — data curation, investigation, resources S.M.M.– software, investigation, software, B.Z.N.—investigation, software, software, D.P.M.— investigation, resurces, O.A.T. — conceptualization, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.