1. Introduction

Worldwide, an estimate of 240 million children lives with disabilities (accounting for one-third of individuals with disabilities), with a vast majority living in middle to low-income countries where access to healthcare resources is limited [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Notably, access to educational and rehabilitation services is crucial to the success of the inclusion of all children, regardless of their conditions [

2], as are exposure to nurturing relationships and positive social norms and beliefs [

2]. The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) advocates for the rights of all children to opportunities for survival, growth, health, and development. A second convention, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), specifically identifies children with disabilities as rights bearers who should be considered in all policies and programming worldwide.

Countries of Sub-Saharan Africa are home to many children with disabilities, many of whom lack access to basic healthcare services [

5]. The 2021 UNCF report shows that, most African nations have incomplete records of disability statistics, that are further limited to impairment-based prevalence data and largely focus on the most visible forms of functional limitations (e.g., physical disabilities) [

6,

7]. Nonetheless, the World Report estimates Disability Prevalence for moderate and moderate-to-severe disability in the population of Africa is 3.1% and 15.3%, respectively [

6]. The foremost cause of disability in Africa is infectious and communicable diseases. Considering the above lack of access to basic healthcare services in many low to middle-income countries, this creates a worrisome picture as, given adequate access to healthcare services, about 65% of the disabling conditions in childhood are preventable [

8]. The Global Population Reference Bureau [

9] (Cook, 2013) predicts that, by 2050, the world’s third most populated country will be Nigeria, now with a population of over 200 million and a growing economy over the past decade [

9] (Kuo, 2013). Favored by these more optimal economic conditions, Nigeria models its education and health systems for other African countries to follow suit. Hence, Nigeria, known as the “Giant of Africa”, plays a leading role in ensuring compliance with the CRC and CRPD recommendations for childhood disability rights and models proper access to healthcare for other Sub-Saharan countries.

Nigeria, the largest country in West Africa, signed and published its first Disability Act in 1993. More recently, it was a signatory to two UN Conventions that included specific clauses for children with disabilities: 1) the CRC, the most widely ratified international human rights treaty in history, which set out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of children [

10], and 2) the CRPD, intended to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. Nigeria signed the CRC on the 26th of January 1990, and ratified it on the 19th of April 1991. The CRPD was signed and ratified later, on March 30th, 2007, and September 24th, 2010, respectively. Both Conventions state that children with disabilities have the same rights to health care, nutrition, education, social inclusion and protection from violence, abuse and neglect, as other children. International law obliges countries that ratify these international treaties to actively implement and monitor their implementation into domestic policies and programs. They are also required to comply with the UN in their cyclical review process and submit reports on progressive implementation of the Conventions. The process of implementation into domestic policy requires a careful and ongoing assessment of existing policies, institutions, and structures. There have been eight CRC reporting cycles for Nigeria and four reporting cycles for the CRPD since their ratification, as required by the United Nations Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (UNOHCHR). Of the eight reporting cycles for the CRC, Nigeria has only responded to four cycles (i.e., Cycle 1:1996, Cycle 2: 2005, Cycle 3 and 4: 2010). These have all gone through the process of review and revision by the UNOHCHR. Of the four CRPD reporting cycles, Nigeria has only responded to one cycle (Cycle 1: 2012 but reported in 2021). However, this reporting cycle has not been reviewed or received feedback from the UNOHCHR as only a State Report was submitted. According to the UNOHCHR website, expectations of comparable submissions by other countries to the CRPD include a State Party report, list of issues (LOI), and information from Civil Society.

It is currently known that children with disabilities continue to face violations of their rights when they are denied adequate health care, nutrition, education, and protection from violence [

10] (OHCHR, 2013). Simeonsson (2000) concluded that ensuring access to appropriate support, such as early childhood intervention and education, can enact the rights of children with disabilities, promote rich and fulfilling childhoods and prepare them for full and meaningful participation in adulthood [

11]. However, the discussion on disability rights frequently focuses on adults, and most child-related initiatives often do not consider the specific needs of children with disabilities. Most African countries have policies and legislation related to disabilities but have yet to realize an accessible and equitable continuum of healthcare in rehabilitation [

12]. In sub-Saharan African countries, accessible healthcare, rehabilitation services, when available, are limited to urban areas [

5]. Furthermore, the plan of action on adoption of the CRC and the CRPD was to establish a guiding framework around which national government, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) recognize violations in human rights and develop additional measures to ensure the realization of these rights [

13,

14]. The intention of the reporting cycles for the conventions is to provide a comprehensive set of standards, which embrace most aspects of children’s lives. In addition, it evokes a language of rights and entitlement by which to frame indicators as well as national and international mechanisms for scrutiny [

15].

Several international agencies have proposed strategic plans and normative frameworks to support the elaboration of policies that consider structural aspects supporting health and well-being for marginalized groups in an equitable manner. In particular, the improvement of the developmental outcomes for participation and protection of children and youth with disabilities has been the objective of a long-term strategic collaboration between the UN, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the UNICEF [

16,

17]. One of the key outcomes of this strategic initiative was the identification of the urgent need to support early childhood intervention for children with disabilities and their families [

18]. As itemized in

Table 1, the WHO Report on Disability [

17] conveyed nine recommendations such as enabling access to all mainstream systems and services among others for the implementation of policy and practice in the field of disability in Nigeria. Policy and service models must be carefully crafted to consider the needs of populations that face multiple levels of marginalization. The development of collaborative approaches across levels of government and sectors is required to positively impact existing barriers to accessing essential services for these groups [

12]. A systematic use of normative frameworks to guide policy elaboration and service delivery systems is a promising way to support the reduction of inequities experienced by children with disabilities in Nigeria [

12].

In 1993 and 2003, Nigeria established and updated a Disability Decree, which has not been updated since the ratification of the CRC in 1991 and the CRPD in 2010. Furthermore, although recommendations have been made by the UN CRPD Committee in 2007, no implementation or monitoring plan has been specified, neither has a specific childhood disability policy been developed. This gap in implementation can be addressed by mapping the existing policies to the CRPD and CRC Articles to interpret the current state of implementation of normative frameworks for human rights in childhood disability. A careful examination of existing reports to the UN Conventions, federal and national policies regarding the rights of children with disabilities may inform advocacy efforts, rights promotion, and policy development for children with disabilities and their families. Therefore, the purpose of this policy review was to examine the extent to which Nigeria has integrated the United Nations’ CRC and CRPD into its current childhood disability policies. Specifically, this policy review, 1) identifies the Nigerian national and subnational policies on childhood disability, 2) examines these policies within the context of the country’s obligations to the UN CRC and CRPD.

3. Results

Search Strategy and Policy Document Selection

The search identified a total of 26 documents, of which 14 met the criteria for inclusion. Included were eight Nigerian CRC government reports from the most recent reporting cycle (i.e., a combined report for the 2008 & 2010 cyclical years) of the CRC and six other Nigerian disability and childhood disability policy documents. No complete CRPD reports were found at the time of the search. Therefore, in the discussion of the results, all the Nigerian CRC reports will be referred to by their titles as no CRPD reports were included in this review. The same will apply to the policy documents.

Table 3 lists the identified documents and reasons for exclusion.

Analysis and Synthesis

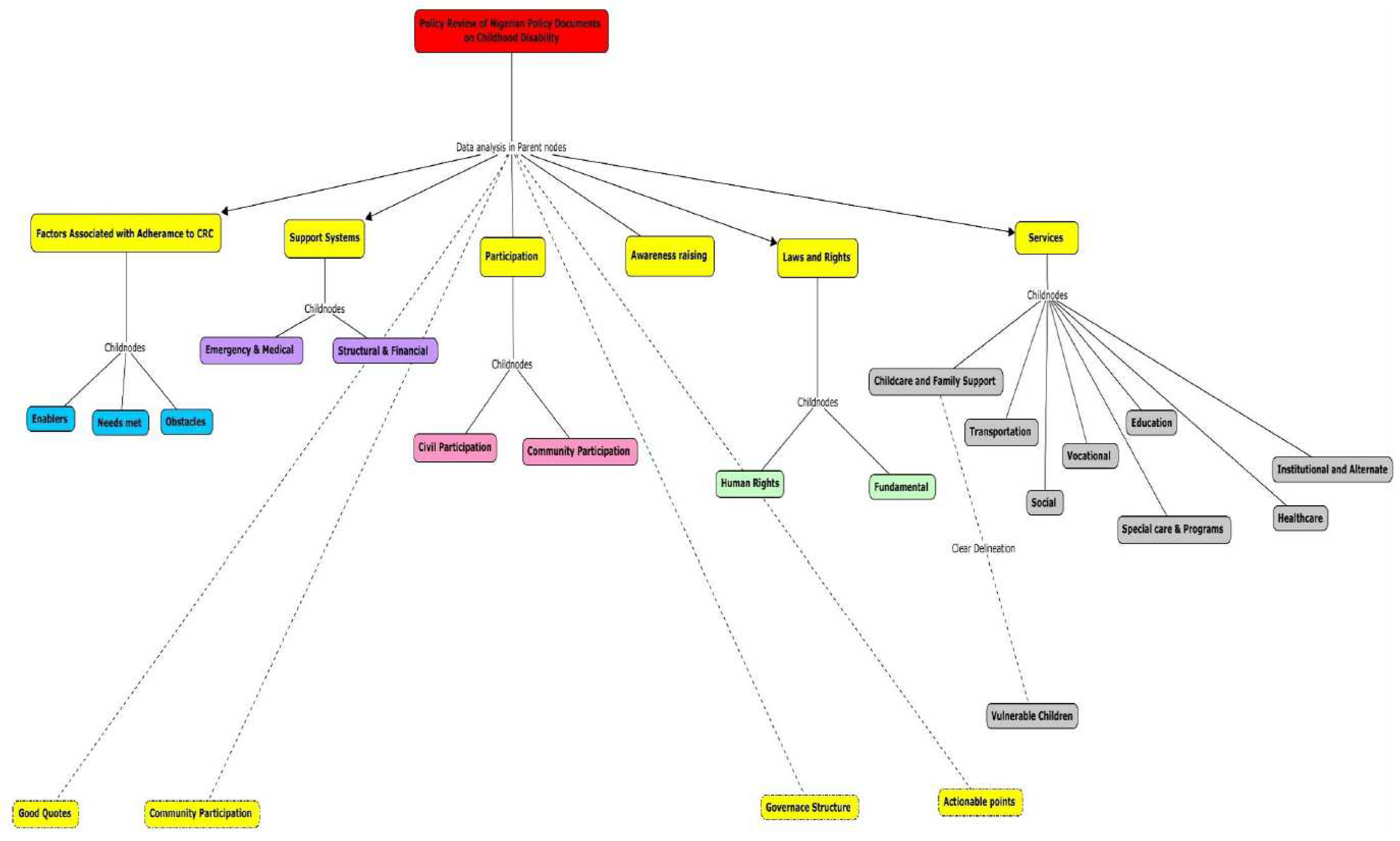

The CRC and CRPD articles that produced the highest keyword frequency (

Table 4) in the text mining and were used to develop the initial coding framework in NVivo are depicted in

Table 5. In this section, the articles and policy documents would be referred as their original document and year name to ensure clarity. Using these articles as a guiding framework, six analytical themes were identified, as shown in

Table 6 with their associating document and reports. They included: 1. participation, 2. support systems, 3. awareness raising, 4. factors associated with adherence to CRC, 5. laws and rights, 6. services. The outline of the themes and subthemes in this policy review is presented in

Figure 1.

Theme 1: Participation

This addressed the policies, laws, and programs developed to integrate children with disabilities into the community in the areas of education, recreation, and vocational development, and those ensuring that the voices of children with disabilities were included when developing childhood disability policies or laws. Two sub-themes were identified: i. Civil Participation, and ii. Community Participation.

i. Civil Participation, focused on the involvement of children with disabilities and their families in policy development, and advocacy, and other civil rights related to disability. It is important to note that because there were no complete Nigerian CRPD reports included in this policy review, not much aligned to the CRPD. Nonetheless, the CRPD articles 7, 8 and 23 mandated the existence of a comprehensive national disability awareness raising strategy aimed at combating stereotypes against persons with disabilities and promoting awareness of their rights which is well corroborated in the awareness raising theme. The CRC reports emphasized the rights of children and young people to know, express, and promote their opinions to be heard in any process involving them as guaranteed under the Child Rights Act (CRA), 2003 (Additional Summary Record, 2010) and through establishment of Child Rights Clubs in schools (State Party Report, 2008). These child rights clubs incorporated the relevant provisions of the CRC. The 2010 CO welcomed the establishment of the Children’s Parliaments in all 36 states in line with the CRC recommendations, to ensure that children were consulted in the process of budget allocation and their active participation in international and national forums such as the Day of the African Child, etc. (State Party Report, 2008). The Parliament was institutionalized to provide a platform for children to dialogue with leaders with a mandate to represent the voices, and aspirations of the Nigerian child, while advocating for their survival, protection, development, and participation in their own rights (State Party Report, 2008). However, despite this effort at inclusion, it is unclear if children with disabilities are designated members of the Children’s Parliament and have a play in actual decision-making. In 2008, the State Party Report noted that participation opportunities for children in matters concerning their rights and welfare had progressively increased over the years since the ratification of the CRC and establishment of the Children’s Parliament. However, the CRC committee still expressed concerns about the limited participation of children in matters affecting them in children’s institutions of all kinds (family, community, judicial, and administrative procedures).

ii. Community participation, covered aspects related to participation in different areas of community life (e.g., access to the community; physical accessibility of public spaces). For instance, the Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) issued building codes and directives to accessible design such as including the requirements for lifts and ramps. A five-year transition period from the date of the law’s commencement was given for all public buildings, roads, pedestrian crossings, and all other structures to be modified, accessible, and usable by persons living with disability. The Disability Decree (1993) assured structural adaptation of all educational institutions to the needs of persons with disabilities as much as guaranteeing physical accessibility to public institutions and facilities. However, although children with disabilities would benefit from the measures outlined in the Disability Decree in public spaces and services, there were no specific mentions of needs of children identified other than the provision of these structural adaptations. The decree also asserts that “It is the responsibility of all organs in the Federal Republic of Nigeria to provide for the disabled; access and adequate mobility with its facilities and suitable exits for the disabled” (Disability decree 1993 p.4). The reply to LOI (2010) notes that, in some states children with disabilities have access to scholarships, free medical, school bus, recreation facilities, book subsidies, and other accessibility equipment. Both the Nigerian Child’s Rights Act (CRA) (2003) and the Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) aim for the rights of children to access training, health care, rehabilitation services and general improvements for persons with disabilities.

Theme 2: Support Systems

This theme describes the framework needed to provide support for children and families of children with disabilities. Two sub-themes were identified: i. Emergency and Medical support and ii. Structural and Financial support.

i. Emergency and Medical support addressed the assistance or essential support for basic needs provided in the context of childhood disability to the children and their families as a temporary aid in times of crisis or difficult circumstances. The Disability Decree (1993, p.5) asserted “the responsibility of the government to provide for the disabled such as acquisition of prosthetic devices and specialty services; a programme to assist the families of the disabled to adjust to disability etc.”. The decree also noted that people with disabilities are to be provided free medical and health services in all public health institutions. The 2008 State Party Reports identified notable action points on support provided to persons with disabilities. These notable actions included the establishment of the Emergency Preparedness and Response Project (EPR) for children in situations of emergency (State party report 2008 p.120). Other examples include and are not limited to: Adamawa State Maternity Assistance to Women and Child Care Law (2001), Bauchi State Hawking by Children (Prohibition) Law (1985), etc., (State Party Report, 2008). Immunization and food fortification program were part of an annual government plan to effectively detect, control and eliminate the outbreaks of diseases affecting child health, growth, and development, with disease causing more impairments and disabilities in children receiving more attention.

ii. Structural and Financial support, referred to help provided by the government or other establishments for children with disabilities and their families. The Lagos Disability Bill (2010) established a Lagos State Persons Living with Disability Fund to advance the cause of persons living with disability in the state. Steps to ensure the self-reliance of and give adequate assistance to persons living with disabilities who desire to be employed were noted to have been followed through by the Government. In 2010, the Lagos State Disability Bill clearly directed that government take steps to ensure the self-reliance of persons living with disability and accordingly give adequate assistance to those who desire to be employed. The CRA (2003) asserted that the services provided by a State Government included conditional or unconditional assistance given in kind or, in exceptional cases, in cash. Despite the support system efforts by the Nigerian government, the committee report in the CO (2010) recommended that the State Party take all necessary measures to ensure the allocation of appropriate support programmes that assist parents, especially single-mothers and teenage households, or legal guardians, in the exercise of their responsibilities (CO, 2010). However, there was no mention of provision or support peculiar to children with disabilities.

Theme 3: Awareness Raising

This theme incorporated education and sharing knowledge about the rights of children with disabilities. Two sub-themes were identified: i.) Public-at -Large Awareness Raising, addressed the general awareness of individuals and the community about disabilities and rights of the child with a disability and ii.) Government-led Awareness Activities consisted of activities, policies, initiatives on raising awareness on topics of childhood disability at the national level. However, both themes were merged following similarities as the government spearheaded the initiatives and created directives for community members to carry out public awareness raising activities. The adoption of the CRPD, has since caused for a replacement of terms defining disabilities such as “persons with a speech disability”, “persons with impaired vision” or “persons with a hearing disability” (Additional Summary Record 2010 p.8). The Summary Report (2010) also confirmed that “the age of majority had not yet been changed to 18 years old in some states and that the federal government was making the best of that situation because it favored dialogue and awareness-raising” (Summary Record 2010 p.5). The Government’s intention was to avoid a clash with the states concerned, so as not to dissuade them from adopting the CRA (2003), which was a short-term priority. However, there was no mention in this context of the age of majority for children with disabilities. The State Party Report also noted that necessary awareness campaigns not explicitly described in the Summary Record (2010) on the age of majority would continue, to ensure transfer of child-related issues into concurrent legislation. Cultural resistance to the CRA (2003) was identified by the State Party Report as an issue. Assistance of the federal authorities was requested in supporting awareness campaigns that involved religious and traditional leaders in the states that had not yet ratified the CRA. The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) noted that there was a need for re-orientation and education of the public on an informed attitude towards persons living with disability.

Theme 4: Factors Associated with Adherence to the CRC

This theme encompassed only factors associated with adherence to the CRC, as Nigeria had not reported back to the CRPD on its first cycle which was overdue (October 2012). Recently, Nigeria submitted a State Party Report to the CRPD (March 2021). However, no LOI report or Civil Society Report was submitted, which means the report has not undergone the review process and hence cannot be included in this review. In 1991, Nigeria ratified the CRC, and, accordingly, every child should not be denied the right to health care services. Incorporated in this right are three provisions: 1) medical assistance and health care to all children, 2) adequate pre- and postnatal care for mothers, 3) access by all segments of society to basic knowledge of child health, nutrition, environmental sanitation, and child health-related issues. Since its ratification in 1991, Nigeria has worked with the CRC to ensure these agreements are achieved. Hence, this theme was described to reflect influential or associated factors regarding adhering to the CRC. Three subthemes were identified: i. Obstacles; ii. Enablers; and iii. Needs Met.

i. Obstacles, included barriers that the Nigerian government faced in implementing the Conventions (

Table 7). According to the Additional Summary Record (2010), a proposed study on providing free health care for mothers and children was not deemed feasible. However, a new budget line was established later that year for the implementation of a healthcare program for mothers, newborns, and infants. Also identified in the Additional Summary Record was the lack of specific budget resources to children, however ministries such as the Ministry of Health or Education provided a budget line for child issues.

Table 7 describes other issues arising. The CO (2010) outlined the efforts of the State party to raise awareness of children’s rights through training and sensitization programs for critical target groups. On review, the CRC committee recommended training for all professional groups working with and for children, including necessary revisions of training manuals and operative procedures (CO, 2010). However, there were concerns that discrimination against children prevailed, particularly among young females, and children with disabilities, unhoused children, and children of ethnic minority groups (e.g., the Ogboni community, Niger Delta region of Nigeria). Furthermore, there were concerns about the lack of information following the Convention’s recommendations relating to children with disabilities where no comprehensive policy had been developed. Also noted by the committee in the CO (2010) was the use of offensive and derogatory, definitions and categories employed by the State party when referring to children with disabilities. In the Summary Record (2010), regrets were expressed that 12 states had still not adopted the CRA despite the State’s efforts to incorporate the Convention into domestic law. The State Party Reports (2008) acknowledged challenges (religious and civil strife, economic constraints, unemployment, and heavy debt) faced by the country which may have impeded progress on the full actualization of child rights outlined in the convention as well as other obstacles outlined in

Table 7.

ii. Enablers (

Table 8), summarized the actions taken by the Nigerian government to facilitate implementation of the Convention at a systems level. These included efforts made at the federal, state, and local government levels in Nigeria to actualize the provisions of the Convention and ensure its effective practical implementation. Following the inauguration of the Children’s Parliament in 2000, all 36 states and the federal capital territory till date is recorded to have functional parliaments, a measure to ensure respect for the views of the Nigerian child (State Party Report, 2008). Although the committee welcome the establishment of the children’s parliament, there is concern about the limited participation of children in matters affecting them in institutions of all kinds and urges the state party to strengthen the functioning of the Children Parliaments, ensuring proper representation of all children (e.g., orphans, children with disabilities, refugee children etc.) (CO, 2010). The Additional Summary Record (2010) requested information on the implementation of the principle of non-discrimination. Two examples of actions taken by the Government to combat discrimination were cited. The first example was the introduction of “child-friendly schools” in the Nigerian Northern States to encourage female school enrolment. In this context, a “child-friendly school” demonstrated parity between the sexes (Additional Summary Record, 2010 pp.7-8). However, there were no specification on the availability of this initiative for female students with disabilities. The second example demonstrated the efforts made to raise the profile of prominent women and make them better known in the country’s various regions to promote a positive image of women, offering role models with whom children and the public could identify (Additional Summary Record, 2010). Although these factors relate to vulnerable groups of children, there was no particular mention of children with disabilities. Other convention implementations steps include the timely data collection on issues relating to children with disabilities for more effective intervention as highlighted in

Table 8 and increased provision for equal educational opportunities for all children, irrespective of their disability.

iii. Needs Met (

Table 9), summarized the factors that were described as facilitating the implementation of the Conventions, where needs of children with disabilities were met by the Nigerian government. The Summary Record (2010) also noted the formulation of the National Child Policy with clear objectives to establish an environment conducive to the exercising of rights described in the Convention. The Nigerian government then developed guidelines on the management and monitoring of childcare institutions, including orphanages, and established family courts in eight states and the Federal Capital Territory to support implementation of the CRA (2003). However, these guidelines didn’t specify the provision for or inclusion of children with disabilities in the management and monitoring of childcare institutions. According to the State Report, 2008, provisions of the CRA guaranteeing special protections measures for children, and the implementation, has improved with the adoption of the Act by many states of the federation.

Theme 5: Laws and Rights

This theme included laws in the Nigerian policy documents that reflected mechanisms supporting the legalization of rights, such as penalties and complaint mechanisms. Subthemes identified were, i. Human Rights Laws, ii. Fundamental rights.

i. Human Rights Laws included all the Nigerian policies and laws relating to childhood disability. The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) (

Table 10) clearly noted that “disabled persons shall have equal rights, privileges, obligations, and opportunities before the law” (Disability Decree 1993 p.1). In relation to children, the CRA (2003) states that every child has a right to survival and development and, where a caregiver with custody of a child fails in their duty, is liable on first conviction to a reprimand conviction with community service and on second conviction to a fine of two thousand naira or imprisonment. Additional information on the Reply to LOI (2010) highlighted the plan of the government to ensure the protection of the most vulnerable children through improved policy and legislation. The Disability Decree (1993) also stated that all persons with disabilities will be guaranteed equal treatment and the government will be responsible for adopting and promoting policies to ensure the full integration of persons with disabilities into the society.

ii. Fundamental Rights include the right to clean food, water, clothing, and an overall good standard of living (welfare, social development, poverty reduction) for children with disabilities and their families. The CO (2010) noted the amendment to the constitution with a view to guaranteeing the right of the child to the best attainable state of physical and mental health as a constitutionally protected right. This was implemented with a view to specify the respective powers and responsibilities of federal, state, and local governments in the delivery of health care. The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) stated its responsibility for the receipt of complaints from persons living with disability on the violation of any of his or her rights; actualizing the enjoyment of all rights in this law by persons living with disability as detailed in

Table 11. Accordingly, the government shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that the rights of persons living with disabilities are guaranteed (Lagos State Disability Bill, 2010).

Theme 6: Services

The CRA (2003) stated that every person, authority, or institution responsible for ensuring the care of a child in need of special protection measures shall endeavor to provide the child with such assistance (education, employment, rehabilitation, and recreational opportunities) to their achieving the fullest possible social integration. According to the Reply to LOI (2010), the Federal and State Governments, alongside NGOs and religious organizations have been active in the provision of services for the children with disabilities with measures and policies to protect their rights. Hence, this theme addresses the policies on services provided for children with disabilities and their families. Eight sub-themes were identified: i.) Childcare and Family Support, ii). Transportation, iii.) Social, iv.) Vocational, v.) Special Care and Programs, vi.) Education, vii.) Healthcare, viii.) Institutional and Alternate Care.

i. Childcare and Family Support: The Disability Decree (1993) stated that Government would ensure that policy guidelines for housing took into consideration the needs of the disabled. The government was mandated to provide for persons with disabilities, subsidized accommodation, apportion not less than 10% of all public housing, improve accessibility to existing housing facilities, and assistance with childcare services. Postal agencies were mandated to provide persons with disabilities with free postal services for all materials to support access to learning aids and orthopedic devices. The CO Report (2010) recommended that the State Party take all necessary measures to ensure the allocation of appropriate financial and other support for caregivers to exercise their responsibilities. The main goal of the NPA was to ensure that improved quality programs and services are implemented for the protection, care, and support for vulnerable children and their caregivers, through improved policy and legislation (Reply to LOI 2010). Section 16 (2) (d) & 17 (3) of the Nigerian constitution recognizes children with a physical and emotional disability as a vulnerable group that needs to be supported financially, materially, technically and be protected from all forms of exploitation and abuse. At the state level, the government is mandated to undertake provision of early and comprehensive information, services, and support to children with disabilities and their families with no separation of child from parent based on a disability of either of both parents (Lagos State Disability Bill, 2010)

ii. Transportation included services offered by the government through the policies for children with disabilities and their families. The Disability Decree (1993) noted that a disabled person was entitled to free transportation by bus, rail, or any other conveyance (other than air travel) that serves the public. Public transport systems are required to adapt vehicles and make them accessible for needs of the disabled with priority granted in all publicly supported transport system and reasonable number of seats reserved solely for the use of persons with disability. Subsequently, the Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) noted that, to ensure the convenience and safety of a person with a disability, all transport service providers should make available, and mark appropriately one out of every 10 seats in in vehicles, vessels, trains, or aircraft for the use of persons with disability.

iii. Social was associated with the social services provided for children with disabilities and their families. The Disability Decree (1993) on supportive social services stated that the government will provide appropriate auxiliary social services to persons with disabilities. It was also noted that assistance would be rendered in all ways appropriate (e.g., prosthetic devices and medical specialty services, specialized training activities, follow-up rehabilitation services, counselling, self-image programs) assisting the families of the child with a disability. In CO (2010) the UN suggested that Nigeria should ensure strategic budgetary lines for disadvantaged or vulnerable children (e.g., orphans, homeless children, internally displaced children) requiring affirmative social measures (i.e., birth registration and protection), even in situations of economic crisis, natural disasters, or other emergencies.

iv. Vocational addressed skills training for different types of jobs, volunteer (unpaid jobs), and employment opportunities (actual placement and adaptations) and programs for children with disabilities. The Disability Decree (1993) advocated vocational training to develop skills. Accordingly, the government received a mandate to promote the employment of persons with disabilities by establishing centers, training programmes, vocational guidance, and counselling to develop and enhance the skills and potentials of persons with disability. However, it was not clearly stated how this applies to children or youths with disabilities. The Reply to the LOI (2010) noted that various governmental and non-governmental organizations operated vocational training centers, special schools, and homes for children with disabilities in different parts of the country. The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) noted the establishment and promotion of schools, vocational and rehabilitation centers for the development of persons living with disability; with training institutions to facilitate acquisition of special skills by persons living with disability.

v. Special Care and Programs summarized care or programs organized for children with disabilities by the community or agreed upon by the government. The State Party Report notes that “except for the provision made in the rehabilitation centers, there are no general specialized services for physically challenged children” (State Party Report 2008 p.89). However, the cumulative effect of the CRA, 2003 (Sections 11, 13 and 16) guarantees the rights of physically and emotionally challenged children to dignity, self-reliance, and active participation in the affairs of the community (State Party Report, 2008). The Reply to LOI (2010) identified measures to protect the rights of children with disabilities. Most states in Nigeria provide children with disabilities with support gadgets (e.g., crutches, wheelchairs, tricycles, hearing aids, braille machines) to facilitate their development, as well as special sports designed for their convenience and active participation (Reply to LOI Additional Information 2010).

vi. Education, comprised of the educational services offered by the Nigerian government for children with disabilities. According to the 1993 Disability Decree, a National Institute of Special Education was established to cope with the increasing research and development in the education for persons with a disability. The decree outlined the government’s plan to establish special schools with appropriate curriculum for disability conditions, ensuring in-service training of teachers (Disability Decree 1993). It also mandated the government to ensure that not less than 10% of all educational expenditures are committed to the education needs of persons with disabilities at all levels. According to the 2003 CRA, every parent or guardian is to ensure that their child or ward attends and completes primary, junior, and secondary education. The decree mandated that persons with a disability are provided equal, free, and adequate education in all public educational institutions at all levels, and that all schools (pre-primary, primary, secondary, or tertiary) be made accessible, with trained personnel to address their educational development. Furthermore, the needs and requirements of persons with disabilities should be considered in the formulation, design of educational policies and programmes, and promotion of specialized institutions to facilitate research and development (Disability Decree 1993). The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) mandated the government to establish special model schools for persons with disabilities, to ensure education was delivered in the most appropriate languages, modes and means of communication to maximize academic and social development. The Bill asserted that children with disabilities should have equal access to participation in play, recreation, leisure, and sporting activities, in the school system.

vii. Healthcare was associated with the health care services provided to children with disabilities. As stipulated in the CRA (2003), the National Health Bill was the government’s answer to financing health care in order to provide a direct funding line for primary health care, guarantee the rights of the child to the best physical and mental health, ensure the provision of free maternal and child health services, and take measures to ensure nation-wide implementation of the National Health Insurance Scheme (2005). For example, the Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) noted that “any hospital where a person living with a communication disability is being attended shall ensure provision for special communication equipment. The Committee welcomed the information that stated that investment in children’s programs and budget allocations to health and education had increased (CO, 2010). The Committee strongly recommended the State Party to “continue its effort to ensure access to education and health services in all states for all children with disabilities and address existing geographical disparities with respect to available social services” (CO 2010 p.14). The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) also guaranteed persons living with disability unfettered access to adequate health care (free medical and health services in all public health institutions) without discrimination on the basis of disability.

viii. Institutional and Alternate Care referred to services or care offered by the government for children with disabilities and their families in different forms of institutions. In the CRA (2002), the federal government encouraged private organizations to provide services for children in need (e.g., children with disabilities) as permitted by the government. The Act also reiterated the government provision for the reception and accommodation of children who had been removed from family or kept away from home under Part IV of the Act (protection of the children); However, it wasn’t clearly stated to what extent this applied to children with disabilities. The CO (2010) stated that “effective measures to ensure that the rights of a child are heard, respected, and implemented in all civil and penal judicial proceedings as well as in administrative proceedings, including those concerning children in alternative care” (p.8). The Lagos State Disability Bill (2010) noted that the Office would provide and sponsor alternative care for a child living with disability.

4. Discussion

This policy review specifically sought to; 1) identify the Nigerian national and subnational policies on childhood disability, 2) examine these policies within the context of the obligations proposed by the UN CRC and CRPD. A total of eight reports (State Party Reports, statements, summary records, Additional Summary Records, LOI, Reply to LOI, CO) to the UN CRC Committee and six Nigerian childhood disability policy documents were analyzed. In this policy review, we identified that the majority of documents addressed issues pertaining to children or to individuals with disabilities and offer few explicit provisions and indicators specific to children with disabilities.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), [

22] defines disability as neither purely biological nor social but, rather, as the interaction between health conditions, environmental and personal factors. “Similarly, the social determinants of health framework and the ICF promotes a comprehensive understanding of health as a right” [

23] The ICF framework asserts that disability occurs at three levels: as an impairment in body function or structure, a limitation in activity, or as a restriction in participation. In parallel to the mapping of the Nigeria policy documents and reports to the CRC and CRPD articles, the Conventions are considered a part of the complementary rights documents as supported by Underwood et al, 2018 and should be taken into consideration as a framework to promote and monitor the rights of children and children with disabilities while guiding healthcare services, programmes, and services in Nigeria [

24]. The Nigerian policy documents and reports could also be linked to aspects of participation but did not outline enabling mechanisms for implementation in crucial areas for children with disabilities (i.e., play, community participation, evolving civic capacity). Hence, the limited considerations specific to the children with disabilities group is one aspect of intersectionality that leaves space for neglect in policy development.

This policy review was able to identify the following components of a scaffolding structure for the rights of children and children with disabilities in Nigeria: 1) the adoption of legislation enacting the CRA, 2003 in 24 states of the Federation, 2) the adoption of policies and strategies to strengthen the implementation of the Convention (e.g. National Child Policy, National Child Health Policy), 3) the adoption of the NPA which “puts children first as a state policy” and emphasizes health education, and protection of children (CO, 2010, p. 3), 4) a special rapporteur on child rights given the mandate by the State Party to monitor and collect data on violations of children’s rights.

Other important identified actions (

Table 12) in this policy review included Increase in budget allocation to health and education; investment of funds in children’s program; trainings and child rights awareness sensitization programs etc. However, most of these were policy innovations that were not specifically inclusive of children with disabilities. Other policies identified in this review for the rights of children with disabilities include an ongoing survey to gather information on the children with disabilities, provision of special education facilities for children with disabilities. However, there still lacks a development of a comprehensive policy on children with disabilities as noted by the UN committee. Children with disabilities are often overlooked in the implementation and enactment of these conventions [

23]. This results in an unseen gap between services and systems offered for individuals with disabilities and concurrently those offered for children. In a recent review of disability issues in Nigeria, numerous factors were identified as reasons for no notable progress namely: the absence of disability discrimination laws, lack of social protection, poor understanding of disability issues by the public, and poor access to rehabilitation services [

25]. Lang & Upal (2008) recommended in a report among others the need for collection of robust reliable data and advocacy of the passage of disability bills into law [

26].

The mapping process of this policy review identified participation in line with the CRPD (Articles 7, 23). This review discussed specific regulations regarding discrimination as identified by the CRPD (i.e., processes of implementation and monitoring of laws, policies, regulations, and programmes related to persons with disabilities in family life, including the right of children with disabilities to live in a family setting within the community). The aspect of inclusion of children in civic life was well identified in the disability policy documents and reports (E.g., creation of Children’s Parliament). However, there was no mention of inclusion of children with disabilities in Parliament. The importance of being included and having access to an education was forefront in the Nigerian policy documents, however, the conversation included all children, vulnerable children, and children with special needs with no clear delineation of the processes to ascertain true inclusion through implementation and enactment mechanisms. Children living in lower socioeconomic settings are known to be at risk for worse health outcomes of different natures such as asthma and other chronic conditions while children with disabilities in fact are also at risk for lower participation and other key developmental and health outcomes [

27,

28,

29]. Support systems aligned with CRC Articles 20, 23, 28, 31, outlining that children with disabilities have the right to access education, vocational training, health care services, rehabilitation services, and recreation opportunities to help the child attain social integration and individual development. Services mapped the rights of children with disabilities to different types of services such as free education, healthcare, financial assistance for special care, which corresponded with CRC articles 20, 23, 28, and 31. However, “children with disabilities have been subjected to pharmacological interventions that would have been considered unacceptable if carried out on children without disabilities in the same community”[

30] p.108. In Nigeria, there are established teaching, orthopedic and other specialist hospitals, but persons with disabilities have limited access to services by these institutions as provided by the National Health Insurance [

30]. As regards to education, there has been advancement in the commitment level demonstrated for children with disabilities in some Nigerian states, however, there are problems with accommodating and providing quality education such as limited number of special educators and education units in Nigeria, logistic and financial problems on the part of the government causing for high cost of special education in Nigeria [

30,

31].

According to the CRPD (Articles 7, 8, 23) state parties should not allow the separation of children from their parents on the basis of the disability of the child or disability of one or both of the parents. A discrepancy between the provisions in the CRC and the CRPD with regards to alternative living arrangements is currently in debate at the UN as the CRPD insists that state move away from policies of placing children with disabilities in institutional care [

32] (UNICEF 2021). The CRC allows for children with severe disabilities to be placed in alternative, institutional care, while the same is prohibited in the CRPD. According Awj, 2017 institutionalization is a clear violation of the right to health of children with disabilities [

33]. In accordance with the CRPD Article 19, there is focus on the main elements of choice in individualized support that promotes inclusion, prevents isolation, and ensures for general services accessibility for persons with disabilities [

34]. There is a growing consensus that institutionalization is an active source of harm, that doesn’t provide a suitable environment for any child to grow [

33]. Long term placement in institutions can further aggravate intellectual disability or result in serious developmental delays among children who were not intellectually disabled [

33]. Therefore, Awj, 2017 recommends that states implement a national deinstitutionalization strategy with the participation of persons with disability by allocating more funds to provide community-based services, help to families and education to healthcare providers, caregivers, and society bringing in awareness [

33].

Although the Conventions are meant to foster equitable policy development and provide language and specific indicators for its progressive implementation, Mulinge, 2002 argues that the ratification of the convention, passing, and adoption of supportive legal frameworks and the existence of a political will to implement the conventions are necessary but not sufficient conditions and doesn’t guarantee the recognition of children’s rights in Africa as exemplified by this review [

13]. This is evident in the lack of attention to children with disabilities in the other Nigerian policies that pertained to children or persons with disability. The ratification of the CRPD by the Nigerian government and a legislative reform, caused for the enactment of the Child Right Act 2003, Universal education Act, 2004 and Employee compensation Act 2012 with the intent of addressing the rights of persons with disabilities and protect their interest [

30]. However, none of these laws specifically addressed children with disabilities. As itemized in

Table 7, the Nigerian government is aware of the existing disparities in policy as they relate to the implementation of childhood disability rights. Specifically, the absence of civil society reports to the CRC and reports from Nigeria to the CRPD over the past reporting cycle seemed to account for the lack of knowledge on the available, current and implementation process of specific policies for children with disabilities and their families. Other bills sponsored by the National Assembly as well as some governments have enacted several policies and legislations as listed in

Table 9 [CRPD State report, 2021; 30] Despite these policies being inclusive of children, most of the policies which were analyzed in this review addressed child rights but not the rights of children with disabilities. Several policies and legislation have been enacted, indicating the intention of the government to ensure the protection of the rights of persons with disabilities. However, it is observed that implementation remains an issue as several persons in Nigerian living with disabilities are helpless and roam the streets seeking assistance for survival [

30]. This policy review revealed that, since Nigeria’s ratification of the CRC (1991) and CRPD (2010), some disability policies that align with the WHO ICF-CY, CRC and CRPD recommendations have been implemented. Such recommendations include the participation of children in matters that concern their rights and welfare. Although “Disability work in Nigeria is done in a non-coherent manner, persons with disabilities are not consulted by the government when decisions are taken and are sometimes only invited to programmes as an afterthought” [

30] pp.110-111.

The governmental bodies or organizations responsible for persons with disabilities should create an awareness in Nigeria on the available policies, make these policy documents easily accessible and ensure the public (including those in the rural areas) is educated on how these policies can be accessed [

35]. In this policy review, most of the disability policies which were readily accessible following database and website search were federal related bills and just one state related policy (i.e., Lagos State Disability Bill, 2010). However, further search into the reports submitted to the CRC suggested that there are state related policies as itemized in

Table 13 but the content of these documents is still not accessible for review. Therefore, the inaccessibility of these documents could contribute to the lack of postering of these policies into implementation. Missing in the role of ensuring the effective reaching of UN goals / vision of these conventions for children with disabilities is the critical role played by professionals who serve families in the health and education section to advocate for and give voice to, children who may otherwise not have access to needed services [

23]. According to Shikako-Thomas & Shevell, (2018) healthcare providers are change drivers that can promote the rights of populations who have been historically neglected and denied their rights [

23]. Hence, there is a need for healthcare providers to act beyond the clinic and act on changing the communities where their patients live [

23].

The following training initiative has seen the participation of Nigeria and other sub-Saharan African countries: An Inclusive Education Training workshop organized by the Joint National Association of People Living with Disabilities (JONAPWD), west Africa federation of the disabled (WAFOD) and the African Disability forum (ADF) welcomed participants from countries including Nigerian discussing how to move from education to quality inclusive education for all, sharing different advocacy and implementation strategies, and methods to evaluate public policies for progressive and immediate realization. The Bridge CRPD-SDGs training initiative is aimed at supporting organization of persons with disabilities (DPOs) and disability right advocates to develop an inclusive (all persons with disabilities) and comprehensive (all human rights) CRPD perspective on development to reinforce their advocacy for inclusion and realization. This initiative has seen participants from Nigeria at their just concluded train the trainer’s curriculum validation workshop. This 12-year innovation bridging program started in 2010 and has evolved into this comprehensive training that is a model of how accessible and inclusive capacity building initiative can be implemented. However, it remains unknown how the knowledge and information garnered by the nigeran participants of these training sessions are translated for implementation in the society.

In a 2013 study of childhood disability in Nigeria, it was noted that although there exist policies for children, these laws and policies are yet to be implemented due to the insufficient political will, overpopulated environment, poor resources, and corruption as the skills needed to handle these situations are either underfunded or misused [

35]. Therefore, supporting the findings of this review that most of the Nigerian policies, although primarily based on broader populations (e.g., children, women, and persons with disabilities), lack the implementation process for the intended population with no clear provision for children with disabilities. Itulua-Abumere 2013, outlines that the major reasons Nigeria seems to be behind in the safeguarding of children with disabilities is the lack of acceptance of social work and welfare service by the Nigerian society. The complete acceptance, financing, and incorporation of social and welfare services to help persons with disabilities access their necessary needs, and transfer information to relevant bodies is needed [

35]. Therefore, there is a need for the implementation of awareness and training programmes by the government (both federal, state, and local). This will help to increase the Nigerian populations’ acceptance rates of these services, which may lead to the progressive implementation of comprehensive disability policies.

Lastly, the civil society which includes non-governmental bodies, national human rights institutions, individual experts, and children play a significant role in the monitoring and implementation of the Conventions according to article 45 (a) and 33 of the CRC and CRPD respectively. As specified by the social model, which emphasizes the social and environmental context of disability, the government and civil society is mandated to work on removing the obstacles faced by citizens with disabilities in becoming active participants in the various communities in which they live and learn to work [

30]. The Civil Society Report is a mechanism to hold States accountable by presenting an analysis of key events, trends, and implemented policies by the people, for the UN committee to compare against what is provided by the State report. The lack of Civil Society reports for Nigeria poses a challenge to determine the extent to which the State Report aligns with the lived experiences of Nigerians. Accordingly, this is the case in South Africa, as a review of its reporting obligations to human rights bodies and mechanism show that effective civil society involvement in the reporting process is lagging [

36]. As exemplified in Viljoen & Orago, 2014 study, civil society organizations are known to help enhance domestic advocacy through widespread knowledge of any material or document emanating from a human right treaty, with the effect that the national dialogue will be more inclusive and comprehensive for the improved realization of socio- economic rights [

37]. Therefore, it is imperative that governments create opportunities and establish formal mechanisms for human rights institutions such as the JONAPWD and other non-governmental organizations relating to children and children with disabilities to be involved in the monitoring and reporting process to the CRC and CRPD.