Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

11 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Design

2.2. Assessment of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL)

2.3. Dietary Assessment and Laboratory and Clinical Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Logistic Regression Analyses

3.3. Random Forest Regression Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (2020) https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health.

- Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL (2006) Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol 77: 1465-1482. [CrossRef]

- Kudiyirickal MG, Pappachan JM (2015) Diabetes mellitus and oral health. Endocrine 49: 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Holmlund A, Lampa E, Lind L (2017) Oral health and cardiovascular disease risk in a cohort of periodontitis patients. Atherosclerosis 262: 101-106. [CrossRef]

- Michaud DS, Fu Z, Shi J, Chung M (2017) Periodontal Disease, Tooth Loss, and Cancer Risk. Epidemiol Rev 39: 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Kossioni AE, Hajto-Bryk J, Janssens B et al (2018) Practical Guidelines for Physicians in Promoting Oral Health in Frail Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc 19: 1039-1046. [CrossRef]

- Sheiham A, Steele LG, Marcenes W, Finch AW, Walls AWG (1999) The impact of oral health on stated ability to eat certain foods; findings from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of Older People in Great Britain. Gerodontology16: 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Flood KL, Carr DB (2004). Nutrition in the elderly. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 20: 125-129. [CrossRef]

- Tôrres LHDN, De Marchi RJ, Hilgert JB et al (2020) Oral health and Obesity in Brazilian elders: A longitudinal study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 48: 540-548. [CrossRef]

- Dibello V, Zupo R, Sardone R et al (2021) Oral frailty and its determinants in older age: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev 2: e507-e520. [CrossRef]

- Dibello V, Lozupone M, Manfredini D et al (2021) Oral frailty and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neural Regen Res 16: 2149-2153. [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen AE, Allen PF, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH (2010) Tooth loss and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 8: 126. [CrossRef]

- Slade GD (2012) Oral health-related quality of life is important for patients, but what about populations? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 40: 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Adamo D, Pecoraro G, Fortuna G et al (2020) Assessment of oral health-related quality of life, measured by OHIP-14 and GOHAI, and psychological profiling in burning mouth syndrome: A case-control clinical study. J Oral Rehabil 47: 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Slade GD, Spencer AJ (1994) Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health 11: 3-11.

- Slade GD (1997) Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Health 25: 284-290. [CrossRef]

- Rosli TI, Chan YM, Kadir RA, Hamid TAA (2019) Association between oral health-related quality of life and nutritional status among older adults in district of Kuala Pilah, Malaysia. BMC Public Health 19: 547. [CrossRef]

- Lozupone M, Panza F, Piccininni M et al (2018) Social dysfunction in older age and relationships with cognition, depression, and apathy: the GreatAGE Study. J Alzheimers Dis 65: 989-1000. [CrossRef]

- Sardone R, Lampignano L, Guerra V et al (2020) Relationship between inflammatory food consumption and age-related hearing loss in a prospective observational cohort: results from the Salus in Apulia Study. Nutrients 12: 426. [CrossRef]

- Corridore D, Campus G, Guerra F, Ripari F, Sale S, Ottolenghi L (2013) Validation of the Italian version of the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (IOHIP-14). Ann Stomatol (Roma) 4: 239–243.

- Locker D, Slade G (1993) Oral Health and quality of life among older adults: The Oral Health Impact Profile. J Can Dent Assoc 59: 830–3, 837–8, 844.

- Locker D (1988) Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health 5: 3–18.

- Allen PF, Locker D (1997) Do weights really matter? An assessment using the oral health impact profile? Community Dent Health 14: 133–138.

- Lampignano L, Sardone R, D'Urso F et al (2022) Processed meat consumption and the risk of incident late-onset depression: a 12-year follow-up of the Salus in Apulia Study. Age Ageing 51: afab257. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (2020) WHO technical report series 894. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation.

- Swoboda J, Kiyak HA, Persson RE et al (2006) Predictors of oral health quality of life in older adults. Spec Care Dentist 26: 137-144. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson B, Manjer J (2020) Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors in relation to Overweight Defined by BMI and "Normal-Weight Obesity". J Obes 2020: 2070297. [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi K, Armoon B, Higgs P et al (2021) The Association of Oral Health Status and socio-economic determinants with Oral Health-Related Quality of Life among the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg 19: 153-165. [CrossRef]

- Kumar P, Mastan K, Chowdhary R, Shanmugam K (2012) Oral manifestations in hypertensive patients: A clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 16: 215-221. [CrossRef]

- Soltani S, Shirani F, Chitsazi MJ, Salehi-Abargouei A (2016) The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet on weight and body composition in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Obes Rev 17: 442-454. [CrossRef]

- Hession M, Rolland C, Kulkarni U, Wise A, Broom J (2009) Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes Rev 10: 36-50. [CrossRef]

- Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Litaker MS et al (2007) Association between aspects of oral health-related quality of life and body mass index in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 1808-1816. [CrossRef]

- Khongsirisombat N, Kiattavorncharoen S, Thanakun S (2022) Increased Oral Dryness and Negative Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Older People with Overweight or Obesity. Dent J (Basel) 10: 231. [CrossRef]

- Daly RM, Elsner RJF, Allen PF, Burke FM (2003) Associations between self-reported dental status and diet. J Oral Rehabil 30: 964–970. [CrossRef]

- Allen PF (2005) Association between diet, social resources and oral health related quality of life in edentulous patients. J Oral Rehabil 32: 623-628. [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis CB, de Bekker-Grob EW, van Lenthe FJ (2015) Factors affecting food choices of older adults from high and low socioeconomic groups: a discrete choice experiment. Am J Clin Nutr 101: 768-774. [CrossRef]

- El Osta N, Hennequin M, Tubert-Jeannin S, Abboud Naaman NB, El Osta L, Geahchan N (2014) The pertinence of oral health indicators in nutritional studies in the elderly. Clin Nutr 33: 316-321. [CrossRef]

- Pillai RS, Mathur VP, Jain V et al (2015) Association between dental prosthesis need, nutritional status and quality of life of elderly subjects. Qual Life Res 24: 2863-2871. [CrossRef]

- Hugo C, Cockburn N, Ford P, March S, Isenring E (2016) Poor nutritional status is associated with worse oral health and poorer quality of life in aged care residents. J Nurs Home Res 2: 118-122. [CrossRef]

- Dahl KE, Wang NJ, Holst D, Ohrn K (2011) Oral health-related quality of life among adults 68-77 years old in Nord-Trøndelag, Norway. Int J Dent Hyg 9: 87–92. 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Choi JH, Kim MJ, Kho HS (2021) Oral health-related quality of life and associated factors in patients with xerostomia. Int J Dent Hyg 19: 313–322. [CrossRef]

- Henni SH, Skudutyte-Rysstad R, Ansteinsson V, Hellesø R, Hovden EAS (2022) Oral health and oral health-related quality of life among older adults receiving home health care services: A scoping review. Gerodontology [Online ahead of print] 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Elwood PC, Bates JF (1972) Dentition and nutrition. Dent Pract Dent Rec 22: 427–429.

| Ideal BMI | Unfavorable BMI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD |

median (min to max) |

Mean ± SD |

Median (min to max) |

p§ | |

| Sociodemographic Assessment | |||||

| Proportion (%) | 152 (70.40) | 64 (29.60) | |||

| Age (years) | 71.95 ± 5.39 | 70 (65 to 87) | 70.12 ± 4.05 | 70 (65 to 82) | 0.03 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 72 (47.40) | 36 (56.20) | 0.23 c2 | ||

| Female | 80 (52.60) | 28 (43.80) | |||

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.96 ± 2.84 | 26.42 (18.96 to 29.9) | 33.7 ± 4.23 | 32.77 (17.38 to 47.69) | <0.01 |

| Education (years) | 7.39 ± 3.47 | 7 (0 to 18) | 6.84 ± 3.38 | 5 (2 to 16) | 0.21 |

| Nutritional Assessment | |||||

| Lipids Consumption (g/die) | 86.80 ± 52.00 | 78.60 (28.40 to 531) | 85.40 ± 65.10 | 74.00 (33.20 to 501) | 0.32 |

| Carbohydrates consumption (g/week) | 471.00 ± 227.00 | 449 (21.90 to 1382) | 467.0 ± 342 | 402 (52.70 to 2344) | 0.33 |

| Protein Consumption (g/die) | 62.10 ± 24.10 | 59.50 (4.63 to 138) | 86.10 ± 118.00 | 70.50 (33.20 to 887) | 0.11 |

| Alcohol consumption (g/die) | 13.70 ± 18.70 | 10.40 (0 to 105) | 16.30 ± 23.10 | 10.40 (0 to 81.10) | 0.91 |

| Metabolic Biomarkers | |||||

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.60 ± 6.54 | 80 (60 to 90) | 81.40 ± 7.42 | 80 (60 to 100) | <0.01 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 130.00 ± 12.4 | 130.00 (100 to 160) | 136.00 ± 15.4 | 140 (100 to 170) | <0.01 |

| FBG (mg/dl) | 98.41 ± 15.46 | 96 (70 to 166) | 114.77 ± 33.96 | 105.5 (73 to 260) | <0.01 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37.95 ± 7.38 | 37 (23 to 79) | 42.62 ± 12.33 | 40.5 (28 to 101) | <0.01 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 183.33 ± 36.59 | 180.5 (96 to 287) | 182.22 ± 35.26 | 185 (76 to 248) | 0.83* |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 49.34 ± 13.16 | 46.5 (28 to 91) | 45.61 ± 10.71 | 45 (27 to 74) | 0.10 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 113.01 ± 30.45 | 111 (36 to 217) | 113.7 ± 26.81 | 113.5 (55 to 182) | 0.87* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 99.03 ± 44.7 | 92 (28 to 344) | 113.78 ± 50.55 | 108 (39 to 261) | 0.05 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.88 ± 1.3 | 13.9 (10.3 to 16.9) | 13.94 ± 1.25 | 13.7 (11.4 to 16.5) | 0.87 |

| RBC (106 cells/mm3) | 5.01 ± 2.96 | 4.75 (3.58 to 40.8) | 4.79 ± 0.47 | 4.76 (3.95 to 6.01) | 0.88 |

| WBC (103 cells/mm3) | 6.1 ± 1.75 | 5.9 (2.6 to 10.7) | 5.97 ± 1.5 | 5.9 (3.06 to 9.4) | 0.77 |

| Platelets (103 cells/mm3) | 224.74 ± 54.74 | 219.5 (114 to 459) | 231.78 ± 60.75 | 234.5 (110 to 452) | 0.24 |

| OHIP-14 questionnaire | |||||

| Q1 Difficult pronounce words | 0.10 ± 0.44 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.13 ± 0.50 | 0 (0 to 2) | 0.72 |

| Q2 Worsened taste | 0.24 ± 0.70 | 0 (0 to 4) | 0.31 ± 0.82 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.75 |

| Q3 Pain | 1.14 ± 1.12 | 2 (0 to 4) | 1.34 ± 1.13 | 2 (0 to 3) | 0.20 |

| Q4 Uncomfortable to eat | 1.02 ± 1.30 | 0 (0 to 4) | 1.50 ± 1.35 | 2 (0 to 4) | 0.01 |

| Q5 Concern for the mouth | 0.16 ± 0.60 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.31 ± 0.88 | 0 (0 to 4) | 0.18 |

| Q6 Self-consciousness due to oral problems | 0.26 ± 0.69 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.31 ± 0.84 | 0 (0 to 4) | 0.96 |

| Q7 Diet unsatisfactory | 0.12 ± 0.56 | 0 (0 to 4) | 0.21 ± 0.68 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.24 |

| Q8 Interrupted meals | 0.11 ± 0.43 | 0 (0 to 2) | 0.21 ± 0.68 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.30 |

| Q9 Difficult to relax due to oral problems | 0.17 ± 0.55 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.11 ± 0.48 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.42 |

| Q10 Embarrassment due to oral problems | 0.11 ± 0.52 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.20 ± 0.70 | 0 (0 to 4) | 0.31 |

| Q11 Irritability | 0.01 ± 0.16 | 0 (0 to 2) | 0.13 ± 0.53 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.01 |

| Q12 Difficult to do jobs due to oral problems | 0.01 ± 0.16 | 0 (0 to 2) | 0.08 ± 0.45 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.14 |

| Q13 Life less satisfying due to oral problems | 0.01 ± 0.08 | 0 (0 to 1) | 0.06 ± 0.08 | 0 (0 to 3) | 0.14 |

| Q14 Totally unable to function | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0 (0 to 0) | 0.03 ± 0.25 | 0 (0 to 2) | 0.11 |

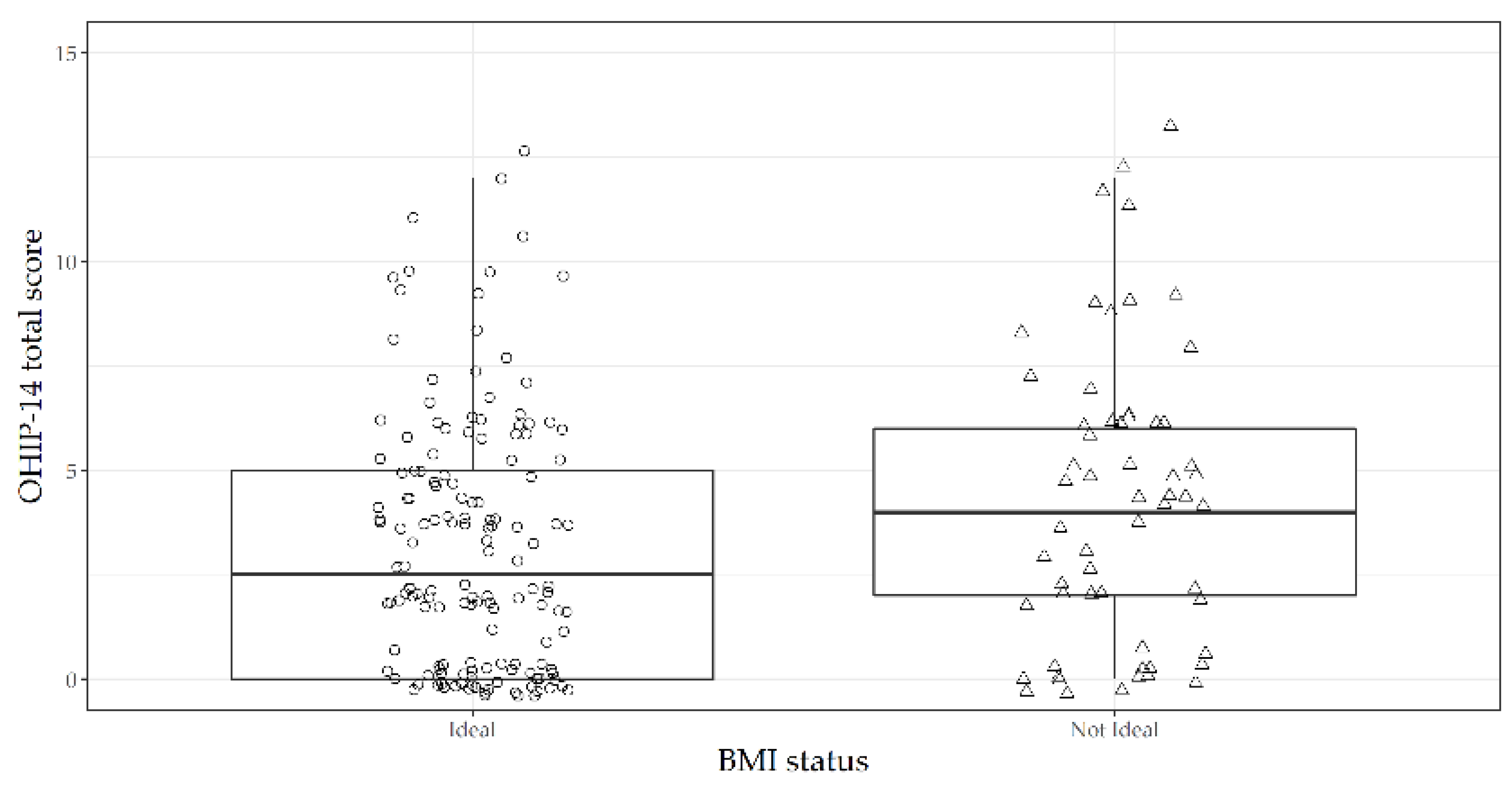

| OHIP-14 Total score | 3.46 ± 3.75 | 2.5 (0 to 25) | 5 ± 5.67 | 4 (0 to 37) | 0.03 |

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| OHIP-14 total score | 1.08 | 1.01 to 1.15 | 0.03 |

| Model 2 | |||

| OHIP-14 total score | 1.10 | 1.01 to 1.22 | 0.04 |

| Age (years) | 0.89 | 0.82 to 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Sex (Female) | 0.48 | 0.21 to 1.11 | 0.08 |

| Education (years) | 0.91 | 0.81 to 1.02 | 0.11 |

| Carbohydrates consumption (g/week) | 1.10 | 0.95 to 1.10 | 0.39 |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | 1.00 | 0.98 to 1.02 | 0.80 |

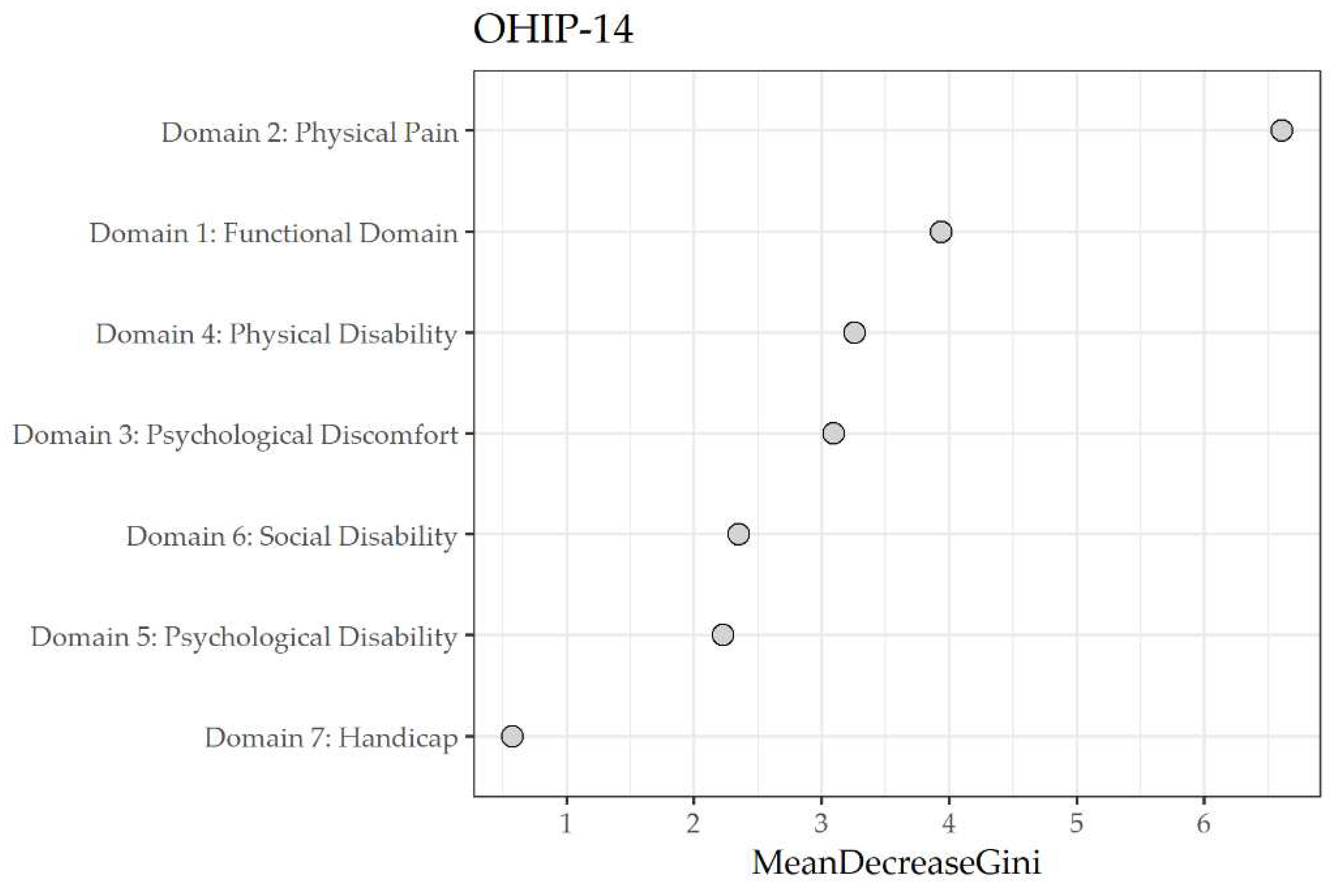

| Domain | Mean decrease Gini |

|---|---|

| 2 Physical pain | 6.63 |

| 1 Functional limitation | 3.54 |

| 3 Psychological discomfort | 3.15 |

| 4 Physical disability | 3.04 |

| 6 Social disability | 2.54 |

| 5 Psychological disability | 2.28 |

| 7 Handicap | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).