Introduction

Sustainable diet contributes to food security and healthy life for the present and future generations, with low environmental impacts (FAO 2010). Sustainable diet produces lower greenhouse gas emission in the environment and offers health benefits (Macdiarmid 2013a). The EAT-Lancet Commission advocated on taking more plant-based food while cutting down animal-based food (Willett et al. 2019). Meat produces high greenhouse gas emission which contributes to climate change, while high saturated fat contributes to cardiovascular diseases. Besides that, taking local or seasonal food have also been one of the elements for sustainable diet (Macdiarmid 2013b). Seasonal food is closely associated with locally produced food (Brooks et al. 2011). Local seasonal food refers to foods produce in the natural production season and consumed within the same climatic zone, which may be more affordable and environmentally friendly. Grocery stores should provide local and seasonal foods which are affordable, along with the information of food origin.

In order to promote sustainable diet behaviour, the consumers need to perceive this behavior is effective in promoting health as well as friendly to the environment. Akehurst et al (2012) demonstrated that perceived effectiveness was strongly associated with environment-friendly purchase behaviour. High perceived effectiveness encourages consumers to translate positive attitudes into actual purchase. On the other hand, the existing barriers to practice sustainable diet behaviour such as price, consumers’ food habits and disbelief in the climate impacts of foods (Mäkiniemi and Vainio 2014) need to be addressed.

Malaysia is a multi-ethnic country with multiple religions and cultures which influence the population’s diet. Some local studies reported organic food and Halal food as safe and healthy for daily consumption, as well as good for the environment and animal welfare (Ahmad and Juhdi 2010, Golnaz et al. 2010). However, there are limited studies on the population’s behaviour on sustainable diet. In order to promote sustainable diet among Malaysians, better understanding of their behaviours on sustainable diet is warranted. It is also important to have a validated tool to measure these behaviours. Therefore, this study aimed to 1) adapt and validate a questionnaire on sustainable diet behaviour, 2) assess the levels of sustainable diet behaviour and its association with socio-demographic characteristics and 3) study the willingness to adopt sustainable diet behaviour using the transtheoretical model, among university students in a public university in Malaysia.

Methods

This study was divided into two phases, namely Phase 1 and II. Both were of cross sectional design. Phase I was to validate the questionnaire assessing sustainable diet behaviour, while Phase II was to assess the participants’ sustainable diet behaviour using the validated questionnaire. The participants for both phases were university students from a public university in Kuala Lumpur and they were mutually exclusive.

Phase I: Validation of sustainable diet behaviour questionnaire

A total of 1020 undergraduate students were recruited using convenient sampling in a university’s leadership program. The questionnaire was prepared as an online Google form and it was self-administered by the participants. Hardcopies were given to those who were unable to access the online questionnaire.

Instrument

The new questionnaire adopted items on sustainable food behaviour from the studies by Bouwman (2016) and DEFRA (2011), with permission. Eight items on perceived effectiveness of sustainable behaviour from Bouwman (2016) were included. These items covered behavioural and psychosocial determinants as well as underlying factors such as individual impact, health benefits, price, essential and importance of practicing sustainable food behaviour. From the study by DEFRA (2011), nine items from the local/ seasonal food theme were selected to be included in the new questionnaire.

Face validation of the questionnaire was carried out among two experts in the field. A total of 17 items in two categories, namely (1) perceived effectiveness of sustainable behaviour, (2) attitude for sustainable food consumption, were compiled. A few modifications were made and agreed by the experts during the face validation process. Modification such as “check the origin / seasonality of products” was changed to “It is too much of an inconvenience to find sustainable food” to give a broader meaning to sustainable food. The answers to the questionnaire were on a five-point Likert scale, which were ‘1 - strongly disagree’, ‘2 - disagree’, ‘3 - neutral’, ‘4 - agree’, and ‘5 - strongly agree’. Higher score indicated better attitude and behaviour towards sustainable diet. The questionnaire was uploaded online in Google Form.

The final part of the questionnaire evaluated participants’ willingness to practice sustainable diet in daily life. A question on ‘If I had a better understanding of the environment impacts of how food is produced’ with four options. The options were made in accordance to the four main stages of the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) (Prochaska, Redding, and Evers 2015) as follows: 1) I would still buy the food I usually buy (pre-contemplation); 2) I would be willing to make change to the food I buy to reduce my impact on the environment (contemplation); 3) I would be willing to take action such as growing my own food (preparation) and 4) I already make changes to the food I buy to reduce my impact on the environment (action).

The questionnaire was translated to the national language of Malaysia (Bahasa Malaysia), using the forward and backward translation method. The translations were carried out by two bilingual professional translators. The translations were then moderated and a final version in Bahasa Malaysia (BM) were derived. The BM questionnaire was translated back to English by another two different translators. The final version in English were compared with the original questionnaire to ensure both had similar meanings. The final translated questionnaire in BM were pilot tested by a few students before rolling out for the study proper.

Phase II: Assessment of sustainable diet behaviour

A total of 1089 students from an orientation program organized by the university were recruited using convenient sampling. Students were invited to fill the validated questionnaire on sustainable diet behaviour (SDB) through the online Google Form. Data were collected within the same time frame for all students. Demographic characteristics such as gender, race, age and study background were also collected.

Data Analysis

Data collected via the Google Form were converted to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The data were then converted into IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Spreadsheet and further analysed. Cases with missing values were deleted to prevent overestimation of precision (Tabachnick and Fidell 2012). All negative items were inversely scored before further analysis.

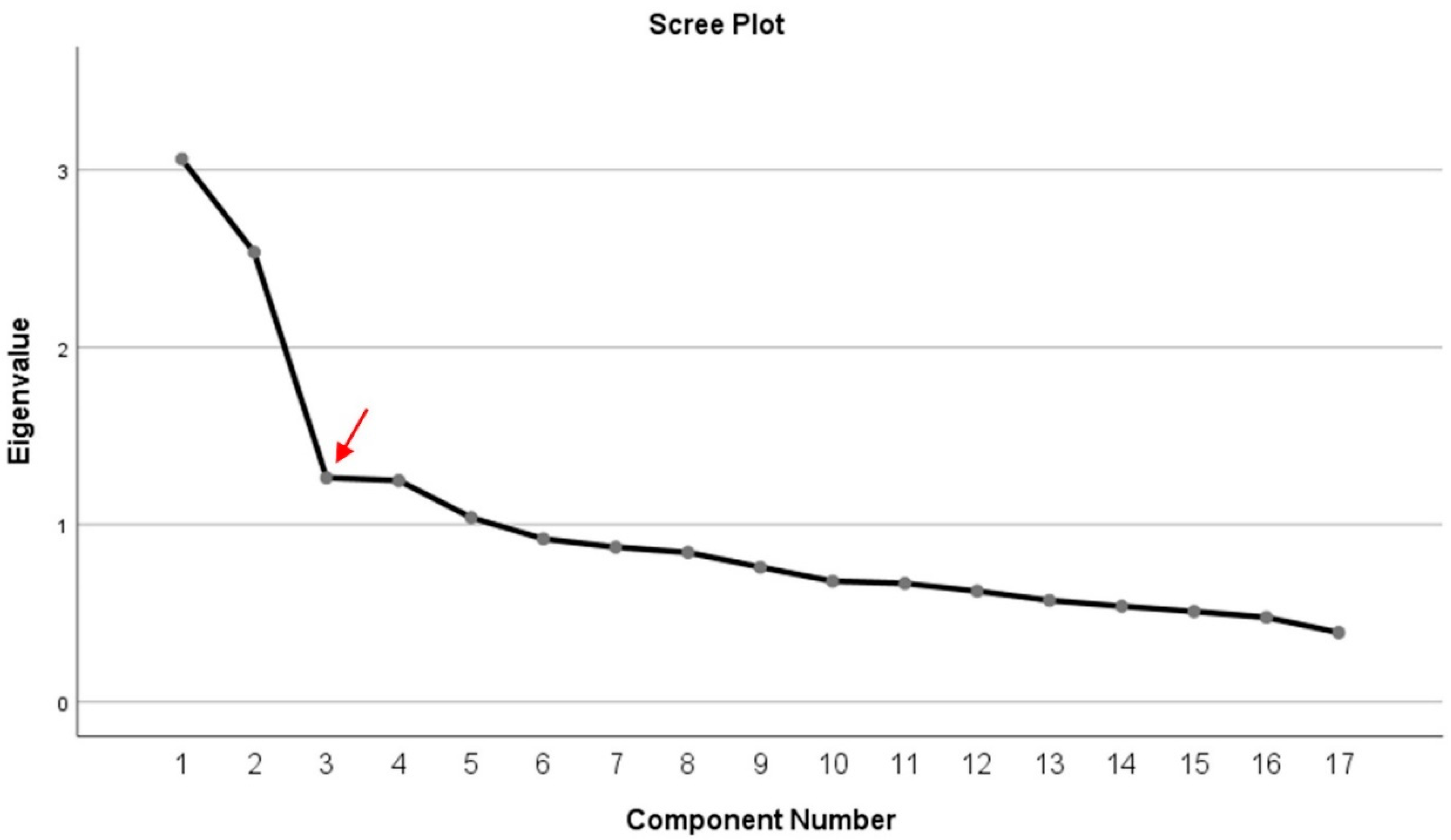

The questionnaire was validated using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) on all 17 items and further confirmed with Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). KMO values and Barlett’s test of sphericity were used to check for appropriateness of data for factor analysis. Factors were retained prior to several consideration as follows: Eigenvalues greater than 1, highest factor loadings, total percentage of variance and scree plot. Cronbach’s alpha was analysed to check for internal consistency.

Meanwhile, descriptive analysis on sustainable diet behaviour scores were reported. The mean differences among gender, ethnicity and study background were analysed via independent sample t-test and ANOVA. Finally, their willingness to adapt sustainable diet behaviour were analysed using ANOVA.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval from the University Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC) was obtained before the study was conducted (Reference Number: UM.TNC2/UMREC - 478). Permission from the university’s Student Affair Division was also obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all students prior to data collection.

Results

Demographic characteristics

There were more female participants for both Phase I and II (

Table 1). Demographic characteristics for both phases were quite similar. There were slightly more Malays, followed by Chinese and Indians. There were almost equal proportions of participants from the Science and Arts background. The mean age of participants was 20.5

+0.9 years old.

Phase 1: Validation of sustainable diet behaviour questionnaire

A total of 658 and 315 undergraduate students were recruited for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), respectively. Their demographic characteristics were presented in

Table 1.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Promax rotation produced a five-factor solution with eigenvalues above 1.0, accounted for 53.8% of the total variance. The 17- items from the original questionnaire were reduced to 12 items with three factors from the EFA. Five of the original items were removed as they obtained factor loading less than 0.5 (Field 2009), while one of the factors contained two items only. The scree plot (

Figure 1) also revealed three data points above the break to be extracted (as indicated by the red arrow).

Prior to the changes made, the PCA with Promax rotation was run again and produced three-factor solution with eigenvalues above 1.0, accounted for total variance of 50.37% (

Table 2), with the rotated factor values ranged between 0.565 and 0.786 (

Table 3). The higher value of factor loading was selected for items with multiple factor loadings. The final three factors formed were retained after taking into consideration that these factors met the required criteria.

Table 4 presented the categorization of the new factors from the original factors. One item (Sustainable food is not expensive) from the original factor on “perceived effectiveness of sustainable behaviour” and two factors from the original factor on “local/seasonal food” were grouped into one new factor (eigenvalues = 1.15) and accounted for 9.62% of total variance. The new factor from EFA were retained and appropriate names were given as best represent the items within the factors (Yong and Pearce 2013). The additional factor was named as “behavioural control”, which included the price, accessibility and availability of sustainable food option when shopping.

Overall, Factor 1 (F1) consisted of five items related to perceive effectiveness on sustainable food behaviour. Factor 2 (F2) had four items on choosing local or seasonal food. Factor 3 (F3) consisted of three items related to behavioural control, taking account the availability, price and preference of sustainable food. The total score for the questionnaire ranged from 12 to 60. Maximum scores for factors 1, 2 and 3 were 25, 20 and 15 respectively.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The final three factors and their distribution of items extracted from EFA were retained and tested for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The fit indices demonstrated that the model with three factors and 12 items was relatively fit (χ2 = 106.83, df = 50, χ2/df= 2.20, GFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.90, AGFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06).

Phase 2: Assessment of sustainable diet behaviour

From the total of 1089 respondents, 66 questionnaires were incomplete. Therefore, the analysis was based on a total of 1023 respondents. Overall, the mean for all items scored above average, ranging from 2.84

+0.94 to 4.35

+0.74 (

Table 5). The item on “It is too much of an inconvenience to find sustainable food ” had the lowest score, while “Environment friendliness is important ” had the highest.

In factor 1 (perceive effectiveness), “Environment friendliness is important” scored the highest. In factors 2 (local/seasonal food) and 3 (behavioural control), ‘My shop does not supply country of origin information of a food product’ and ‘Sustainable food is not expensive’ had the highest score respectively. On the other hand, the lowest scores for factors 1, 2 and 3 were “Perceived positive health effects of sustainable food consumption”, “It is inconvenient to check the origin / seasonality of products” and “Sustainable food is not an option where I shop” respectively. Highest scores showed more positive perception while lowest scores showed negative perception.

Females consistently scored higher than males in all factors as well as the overall mean (

Table 6). However, the differences were not significant except for factor 2 on local / seasonal food (

p < 0.01). There was no significant difference among ethnic groups for factor 1 (perceived effectiveness). On the other hand, students from the Indian ethnicity had significantly (p<0.05) higher mean scores in factor 2 (local/seasonal food), factor 3 (behavioural control) and overall mean, compared to the Malays, Chinese and others. Both Arts and Science students had comparable mean scores for factors 1, 2 or 3 and all factors combined.

Willingness to change

When the students were asked for their willingness to practice sustainable diet in daily life, only 21% were in the action stage and 54.5% in contemplation stage (

Table 7). Students in the pre-contemplation stage had the lowest while those in action stage had the highest mean scores for all individual factors (p<0.01).

Discussion

The adapted and validated questionnaire consists of three factors, namely perceived effectiveness (factor 1), local/ season food (factor 2) and behavioural control (factor 3). From the original list of 17 items, the final questionnaire was left with 12 items with three factors. A new factor, named as behavioural control (factor 3) was created. One item originally from factor 1 (perceived effectiveness) and two items from factor 2 (choosing local/ seasonal food) were grouped into the factor 3 (behavioural control). The three factors were confirmed through EFA and CFA with relatively fit models produced. Both EFA and CFA were performed with large sample sizes to ensure the factors’ stability. The developed questionnaire is valid and can be used to assess the sustainable diet behaviour as well as some insight to its barriers.

The items in factor 3 (behavioural control) were concerns on price, convenience and availability of sustainable food products. It is understandable that price, quality, convenience affect consumers’ behaviour on purchasing food products (Carrigan and Attalla 2001) and their perceived attitude and intention to buy food products (Vermeir and Verbeke 2006). Price, availability and convenience may act as barriers even though the motivation for practicing sustainable food behaviour is high. Local food preference is associated with better diet quality among college students and should be advocated for more sustainable consumption behaviour (Pelletier et al. 2013).

Perceive effectiveness, local/ seasonal food and behavioural control were important factors to assess sustainable diet behaviour. The mean score for the university students on the assessment of sustainable diet behaviour for all factors was moderate (approximately 70%). All students agreed on the importance on environmental friendliness for perceive effectiveness on sustainable diet. Most of them also appreciated sustainable food and agreed that they should consume sustainable food. Those in the pre-contemplation stage had the lowest total score compared to the participants in the stages of contemplation, preparation and action stage.

Meanwhile, there were two items that may be the barriers to practice sustainable diet among the students. The information on the source of a food product and the availability of the sustainable food product were reported to be missing in their local shops. It is important to know the origin of a food product in order to choose local/ seasonal food. In addition, the unavailability of sustainable food products in the local shops restricted the students from practicing sustainable diet behaviour. Instead, consumers in Malaysia are more familiar with labels on food safety and hygiene such as HACCP and ISO, or Halal (according to the Syariah Law) on the food packaging (Abdul Latiff et al. 2016). Sustainable food labels should be displayed on the food items for consumers to identify which food products are sustainable.

In general, females from all ages were more likely to change their eating behaviour upon knowing its benefits on the environment, compared to males, similarly reported elsewhere (Tobler, Visschers, and Siegrist 2011, Siegrist, Visschers, and Hartmann 2015). Regardless of ethnicity, the Malaysians exhibited similar motives in their food choices (Mohd-Any, Mahdzan, and Cher 2014). However, our findings suggested that the Indian students were more likely to choose sustainable food products and local/ seasonal food, compared to the Malays and Chinese. Targeted education should be focus on these ethnic groups.

Participants who appreciated sustainable food, perceive environment friendliness is important and perceived positive health effects of sustainable food consumption may be more likely to be in the preparation and action stages for sustainable diet behaviour. Similarly, participants who checked the origin / seasonality of products and knew the seasonal fruits and vegetables, not associating sustainable foods with inconvenience and cost as well as taking it as an option to shop, were more likely to be in the preparation and action stage for sustainable diet behaviour. Majority of our participants regardless of gender, ethnicities and study background were positive on sustainable diet behaviour. Environmental and sustainability are commonly discussed nowadays, and university students are expected to be aware in this issue. They are the future leaders and should lead the public in practicing sustainable diet behaviour for health as well as the environment.

While interpreting the findings, there are a few limitations that need to be considered. The university students may represent the young adult population, but they may not be representative of the general young adult population in terms of education levels. In addition, the actual sustainable diet behaviour was not measured, but stages of change were used instead. Future studies should be implemented among the general population from a wider age range with different education levels with actual measurement of sustainable diet behaviour. On the other hand, this may be one of the few studies on sustainable diet behaviours in the country and this could serve as the basis for future studies and intervention programs planned in promoting sustainable diet behaviour.

Conclusion

The validated questionnaire is valid and can be used in the assessment of sustainable diet behaviour among young adults. Overall, the students showed positive sustainable diet behaviour. Females and Indians were more likely to purchase seasonal / local foods and choose sustainable food products. Participants in the preparation and action stage for sustainable diet behaviour had higher scores in all factors individually or combined.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to the students for their participation and acknowledge the approval from the university management to conduct the study. This study is funded by the University of Malaya Research Grant (UMRG) Program (No: RP051A-17HTM).

References

- Abdul Latiff, Zul Ariff Bin, Golnaz Rezai, Zainalabidin Mohamed, and Mohamad Amizi Ayob. 2016. "Food Labels’ Impact Assessment on Consumer Purchasing Behavior in Malaysia." Journal of Food Products Marketing 22 (2):137-146. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Siti Nor Bayaah, and Nurita Juhdi. 2010. "Organic food: A study on demographic characteristics and factors influencing purchase intentions among consumers in Klang Valley, Malaysia." International journal of business and management 5 (2):105.

- Akehurst, Gary, Carolina Afonso, and Helena Martins Gonçalves. 2012. "Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: new evidences." Management Decision 50 (5):972-988. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M, C Foster, M Holmes, and J Wiltshire. 2011. "Does consuming seasonal foods benefit the environment? Insights from recent research." Nutrition Bulletin 36 (4):449-453. [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Ahmad Attalla. 2001. "The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behaviour?" Journal of consumer marketing 18 (7):560-578.

- DEFRA. 2011. "Attitudes and Behaviours around Sustainable Food Purchasing." Defra, London, UK.

- Emily Bouwman, Muriel Verain, and Harriëtte Snoek 2016. Consumers’ knowledge about the determinants fo a sustainable diet. SUStainable Food And Nutrition Security.

- FAO. 2010. "FAO Definition of Sustainable Diets " International Scientific Symposium Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United Against Hunger November:4-5.

- Field, Andy. 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS: Sage publications.

- Golnaz, R, M Zainalabidin, S Mad Nasir, and FC Eddie Chiew. 2010. "Non-Muslims’ awareness of Halal principles and related food products in Malaysia." International Food Research Journal 17 (3):667-674.

- Macdiarmid, Jennie I. 2013a. "Is a healthy diet an environmentally sustainable diet?" Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 72 (1):13-20.

- Macdiarmid, Jennie I. 2013b. "Seasonality and dietary requirements: will eating seasonal food contribute to health and environmental sustainability?" Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 73 (3):368-375. [CrossRef]

- Mäkiniemi, Jaana-Piia, and Annukka Vainio. 2014. "Barriers to climate-friendly food choices among young adults in Finland." Appetite 74:12-19. [CrossRef]

- Mohd-Any, Amrul Asraf, Nurul Shahnaz Mahdzan, and Chua Siang Cher. 2014. "Food choice motives of different ethnics and the foodies segment in Kuala Lumpur." British Food Journal. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, Jennifer E., Melissa N. Laska, Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, and Mary Story. 2013. "Positive Attitudes toward Organic, Local, and Sustainable Foods Are Associated with Higher Dietary Quality among Young Adults." Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 113 (1):127-132. [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, James O, Colleen A Redding, and Kerry E Evers. 2015. "The transtheoretical model and stages of change." Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice:125-148.

- Siegrist, Michael, Vivianne H. M. Visschers, and Christina Hartmann. 2015. "Factors influencing changes in sustainability perception of various food behaviors: Results of a longitudinal study." Food Quality and Preference 46:33-39. [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G, and Linda S Fidell. 2012. "Using multivariate statistics." New York: Harper and Row. [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C., V. H. Visschers, and M. Siegrist. 2011. "Eating green. Consumers' willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors." Appetite 57 (3):674-82. [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, Iris, and Wim Verbeke. 2006. "Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap." Journal of Agricultural and Environmental ethics 19 (2):169-194.

- Willett, Walter, Johan Rockström, Brent Loken, Marco Springmann, Tim Lang, Sonja Vermeulen, Tara Garnett, David Tilman, Fabrice DeClerck, and Amanda Wood. 2019. "Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems." The Lancet 393 (10170):447-492.

- Yong, An Gie, and Sean Pearce. 2013. "A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis." Tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology 9 (2):79-94. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).