Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were 257 million positive serology tests for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and 100 million for hepatitis C virus (HCV) globally in 2012 and 2018 respectively. Infections of both HBV and HCV are considered global public health problems [

1,

2]. As per WHO records, the annual global death rates for HBV and HCV are 0.6 million and 0.4 million, respectively [

1,

2,

3]. Statistically, Pakistan has the highest disease burden in South Asia, with a prevalence of HCV of 4.8% in the entire country and 1.1% in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, and a prevalence of hepatitis B of 2.5% nationwide and 1.3% in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province [

4,

5]. The high prevalence of hepatitis B and C can be attributed to a lack of awareness among people regarding the potential complications arising from the excessive use of syringes, unsterilized dental or surgical equipment, razors, and engaging in unsafe sexual intercourse. Many individuals are not fully informed about the risks associated with these practices, leading to higher rates of health problems. 161,000 HCV patients received hepatitis treatment in Pakistan in 2016, mostly via the private sector, as compared with 65,000 in 2015. However, Pakistan must increase this rate to 880,000 treatments per year to reach the HCV elimination target set by WHO’s Global Health Sector Strategy [

6].

Afghanistan, situated west of Pakistan, shares a border with the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan provinces of the latter. Refugees and migrants from Afghanistan mainly enter Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province through the Torkham border located in the Peshawar Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province [

7]. Chemaitelly et. Al and ataullah et. Al found the prevalence of HBV and HCV in Afghanistan to be 6.15% and 0.7%, respectively [

8,

9]. As a major source of migrants entering the region, there is a need to assess the incidence of HCV and HBV in Afghan migrants in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. However, at present, no survey has been done to estimate the prevalence of hepatitis B or C in the refugees or migrants living in or entering Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province.

The development of direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C has made possible WHO’s Sustainable Development Goal 3.3, as part of their Global Health Sector Strategy developed in the 69th World Health Assembly to eliminate hepatitis B and C. The elimination of hepatitis B and C can be made possible by reducing the incidence of hepatitis C infections and mortality by 80% and 65%, respectively, by 2030, relative to levels recorded in 2015 [

10]. A government-run national hepatitis screening program involving a register to keep record of the incidence and mortality of hepatitis in the country—as seen for human immunodeficiency virus, polio, and other endemic diseases—was not available in Pakistan until October 2017, when Pakistan’s government launched the National Hepatitis Strategic Framework (NHSF) (2017–2021). Effective implementation of the NHSF depends on concerted federal and provincial actions from all stakeholders in health and other sectors to respond to viral hepatitis [

11].

Despite the presence of various private-sector hepatitis B and C screening and eradication programs, thousands of cases go undiagnosed due to the lack of awareness of the population, poor patient compliance, and accessibility issues of the general population to the screening venue, as well as the fact that private organizations operate in urban cities, leaving the city slums, rural villages, and peripheries without access [

12].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to provide an overview about the prevalence of hepatitis B and C, as well as the effectiveness of a screening program in a region where there is lack of such programs. In addition, we hope to give an estimation of the influx of Afghan refugees or migrants into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, sharing the hepatitis B and C prevalence, to pave the way for future screening programs for these infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the screening program was obtained from the Rehman Medical Institute Research and Ethics Committee RMI-REC. A mandatory verbal and written consent form in both local and English languages was signed by either the individual or the guardian in the case of minors before testing.

2.2. Study Design and Setting

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is an underdeveloped province in Pakistan with a population of 35.53 million as of 2017. A prospective cohort study design was used to conduct the study. The screening program was carried out from July-28-2018 to December-12-2020 in Rehman Medical Institute, which is situated in Peshawar in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. Rehman Medical Institute is a 500+ bed state-of-the-art tertiary-care medical facility providing preventive, curative, and rehabilitative services to the people of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The hospital treats 201,374 patients per year, which covers almost all of the province’s patient load as well as the migrants from the neighboring country of Afghanistan.

2.3. Participants

Participants were selected with the simple random sampling screening technique, as the program was open to everyone who entered the hospital regardless of ethnicity, age group, gender, or profession. All the individuals were screened for both hepatitis B and C. The screening program involved free screening, free counselling of the positive individuals by an expert counsellor, and free-of-cost medication or vaccination. A total of 9563 individuals were screened.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria: Any individual who had consented (or their guardian) to be tested was included in the study regardless of ethnicity, age group, gender, or profession.

Exclusion Criteria: Any individual who did not consent to be tested was excluded from the study.

2.5. Data Variables

The registry included the date, the patient’s name, registration number, age, personal contact number, address, health worker status, prior screening status, previous antiviral treatment (If Positive), investigations, diagnosis, counselling, treatment advised, visit date, and follow-up.

2.6. Data Collection

An online registry, in the form of an online spreadsheet file, was made for da-ta-collection and surveillance purposes of the screened individuals, which could be accessed by any employee with proper access rights with an account made by the in-formation technology department of the organization. The registry was updated instantaneously whenever an individual was screened or on the day of follow-up. Once collected, the data were cleaned from all spelling mistakes before analysis, and the de-tails of the positive individuals were reconfirmed on the provided cell-phone number or on the day of follow-up.

2.7. Blood Sampling, Diagnosis, and Treatment

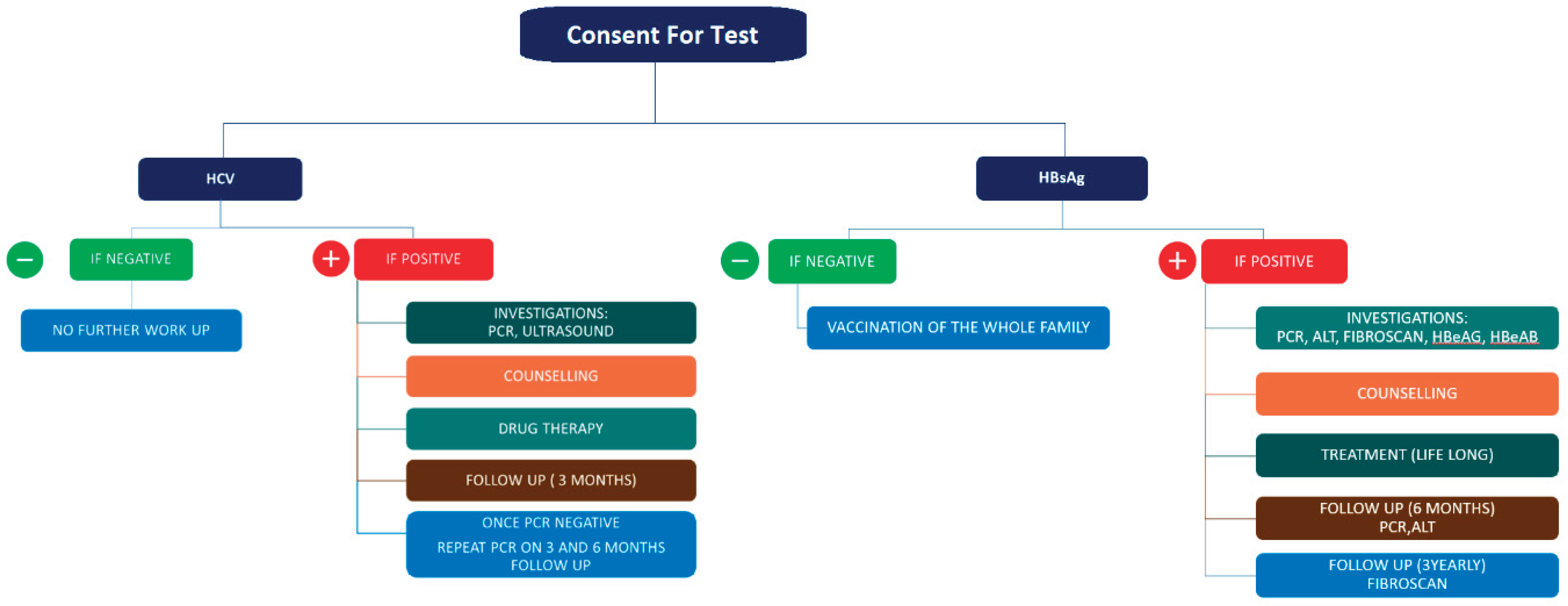

Blood samples were obtained at collection stations installed. Each sample was then transferred to the sample testing kit area where it was then tested. The WHO approved kit ABON™ HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen and ABON™ HCV hepatitis C virus rapid test were used for screening purposes in the program. A pathway was designed to screen patients and then provide proper counselling and treatment if needed (

Figure 1). In individuals with a negative HbsAg test, the individual and their whole family would be vaccinated. If the test was positive, investigations would be advised, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), alanine transaminase (ALT), FibroScan, HBeAG, and HBeAB followed by free-of-cost counselling, proper treatment with an ideal di-rect-acting antiviral drug, a first follow-up with repeat PCR and ALT testing, and then a follow-up with FibroScan, which was advised to be repeated every three years. In the case of HCV, if the test was negative, there was no follow-up. If the test was positive, investigations would be advised, including PCR and ultrasound followed by free counselling, then treatment with an ideal direct-acting antiviral drug or, in the case of hepatoma, referral to an interventional radiologist or transplant surgeon would be done if applicable; this was followed by a follow-up after three months and then again after six months with repeat PCR testing (

Figure 1).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Once obtained from the registry, the data were then analyzed using the SPSS software (version 23; IBM, USA). We applied descriptive analysis for the data tables to get an overview. A normal distribution curve histogram was used for the gender- and age-based distributions. The chi-squared test was used to determine the significance of the parameters.

3. Results

A total of 9563 individuals were screened, comprising 5894, (60.7%) male and 3669 (39.3%) female patients. The mean age of both the male and female groups was 35 (±5) years. The maximum age in the male group was recorded as 105 years, and that in the female group was 92 years. The minimum age in both groups was 1 year. Among the individuals screened, a total of 876 (9.2%) tested positive for hepatitis, in which 538 (5.6%) (383 males and 155 females) were positive for hepatitis B and 330 (3.5%) (198 males and 134 females) were positive for hepatitis C. There were 8 (0.1%) individuals who were positive for both hepatitis B and C showing co-infection, in which 6 were male and 2 were female. Among the positive individuals, 381 were already known cases of either hepatitis B or C, whereas 496 were newly diagnosed, of which only 155 were already receiving antiviral treatment. In positive individuals, only 51 (5.8%) were related to working in healthcare facilities, whereas the rest 825 (94.2%) were not related to any healthcare profession. The rest of the results are given in

Table 1 and

Figure 2.

The overall prevalence in all the screened population was found to be 5.6% (CL 5.2%-6.1%) for hepatitis B and 3.5% (CL 3.1%-3.8%) for hepatitis C. According to the gender-based distribution of hepatitis B, a prevalence of 4.0% (CL 3.6%-4.4%) was reported in male patients and 1.6% (CL 1.4%-1.9%) in female patients, whereas that of hepatitis C was 2.0% (CL 1.8%-2.3%) in male patients and 1.4% (CL 1.2%-1.7%) in female patients. 0.1% (CL 0.01%-0.1%) of male patients and 0.01% (CL 0.001%-0.1%) of female patients had both HbsAg and anti-HCV positive serology (

Table 1;

Figure 2).

Out of the 876 individuals positive for hepatitis, 293 were advised to take direct-acting antivirals, including entecavir 0.5 mg (n=83), ribavirin 400 mg (n=21), sofosbuvir 400 mg (n=22), sofosbuvir 400 mg + velpatasvir 100 mg (n=51), sofosbuvir 400 mg + velpatasvir 100 mg + ribavirin 400 mg (n=29), and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg (n=79). The eight individuals who were positive for both hepatitis B and C were advised to take sofosbuvir 400 mg + velpatasvir 100 mg + entecavir 0.5 mg. Seven individuals were referred to interventional radiologist for hepatoma management with trans-arterial embolization, and six were referred to the transplant surgeon. Follow-up was advised based on the patient’s diagnosis and disease severity: 105 individuals were advised follow-up after three months, 260 were advised follow-up after six months, and 102 were advised follow-up after 12 months. 396 individuals positive for either hepatitis B or C failed to report on their follow-up and therefore did not receive any treatment or follow-up plan (

Table 1).

According to the geographical distribution of hepatitis in the different divisions of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province of Pakistan and in the migrants from the neighboring country of Afghanistan, 206 cases of Hepatitis B and 223 cases of Hepatitis C were found in the Peshawar Division, with a prevalence of 2.2% (CL 1.9%-2.5%) and 2.3% (CL 2.0%-2.6%), respectively. Although many cases (n=258) of hepatitis B were found in the Afghan migrants, with a prevalence of 2.7% (CL 2.4%-3.0%), only 51 cases of hepatitis C were reported in this group, with a prevalence of 0.5% (CL 0.4%-1%). The prevalence of hepatitis B and C was 0.2% (CL 0.1%-0.3%) and 0.2% (CL 0.2%-0.4%) in the Mardan Division, 0.2% (CL 0.1%-0.3%) and 0.2% (CL 0.1%-0.3%) in the Hazara Division, 0.1% (CL 0.1%-0.2%) and 0.1% (CL 0.0%-0.1%) in the Malakand Division, 0.1% (CL 0.1%-0.2%) and 0.1% (CL 0.0%-0.1%) in the Bannu Division, 0.1% (CL 0.1%-0.2%) and 0.0% (CL 0.0%-0.1%) in the Kohat Division, and 0.0% (CL 0.0%-0.1%) and 0.0% (CL 0.0%-0.0%) in the Dera Ismail Khan Division (

Table 2;

Figure 2).

The chi-squared test was significant at the 0.05 level (sig. 0.000*) for an association between gender and positive HbsAg test result, indicating that hepatitis B was more prevalent in males than in females, although no statistical association was found in hepatitis C with either gender group (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The prevalence of HBV and HCV is high in South Asia, including Pakistan and Afghanistan. A screening program for these viruses is necessary to control the spread of infection and prevent severe liver diseases. The results of the screening program in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, which included migrants from Afghanistan, showed a high prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections, especially in the Afghan migrants. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province is considered one of the least-developed provinces in terms of health awareness and public health-management programs. Afghani-stan itself is country with an enormous disease burden of hepatitis B and C, and few studies have estimated the burden from Afghani migrants moving into the province. We found that the incidence of hepatitis B and C has increased over time, largely as a result of the influx of migrants from Afghanistan.

The prevalence of hepatitis B and C previously recorded in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was 1.1% and 1.3%, respectively, which, according to our data, has increased to 5.6% and 3.5%, respectively, over the last 10 to 15 years. A sizable portion of this prevalence is attributed to the refugees and migrants from Afghanistan visiting the province, which see a prevalence of hepatitis B and C of 2.5% and 0.5%, respectively [

4,

5,

8,

9]. This in-creased ratio consistent with previous studies done in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Afghanistan, which proves that the disease progression is still on an increasing trend at an alarming rate. This data indicates that there have been no effective eradication programs against hepatitis, as these would be expected to lead to a decreasing trend. Other studies have attributed this trend to the lack of awareness in the general population about the disease and its risk factors, as well as a poor literacy rate of 43% [

13,

14]. Keeping in view the findings of our study and the studies already mentioned it can be deducted that it is unlikely that Pakistan could meet the goals set by WHO of reducing the mortality and prevalence of hepatitis B and C by the year 2030 [

11].

The high prevalence of hepatitis B and C infections in the local population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province is also concerning. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in Pakistan, which reported a high prevalence of these infections in different regions of the country [

15]. The high prevalence of HBV and HCV in these populations can be attributed to various factors such as poor sanitation, inadequate healthcare facilities, and low awareness about the transmission and prevention of these viruses. The use of contaminated syringes and needles, unprotected sexual contact, mother-to-child transmission, barber shaving, self-flagellation, recreational drug use, circumcision by non-health professionals, piercings, beauty parlor visits, history of blood transfusion, having, and Hijama therapy are some of the common modes of transmission of these viruses [

14,

16].

According to our results, 43.5% of hepatitis-positive individuals (CI 40.2%-46.8%) were previously diagnosed cases, whereas the other 56.5% (CI 53.2%-59.8%) were undiagnosed, which shows that the majority of people were unaware of their diagnosis. In addition, among the previously diagnosed cases, only 17.7% (CL 15.3%-20.3%) were either vaccinated for hepatitis B or received direct-acting antiviral drugs, whereas the other 82.3% (CL 79.7%-84.7%) did not receive any kind of treatment or vaccination, which shows that there is lack of proper education regarding the disease and the need for prompt treatment (

Table 1). Every individual who tested positive for hepatitis was advised treatment or referred to a liver transplant specialist or interventional radiologist for further treatment, except for 19.3% (CI 16.8%-22.0%) of individuals who were either receiving treatment for hepatitis B or C, or were vaccinated for hepatitis B. Another sign of lack of disease awareness was 45.4% (CI 42.2%-48.7%) of individuals who did not report for follow-up. 396 individuals positive for either hepatitis B or C failed to report for follow-up and therefore did not receive any treatment or follow-up plan (

Table 1).

Our study found a strong association between gender and hepatitis B infection. According to our results, hepatitis B infection has a strong association with the female sex, whereas there was no association between hepatitis C with any sex group. Some patients tested positive for both hepatitis B and C, indicating a co-infection. Khan et al. also reported co-infection of hepatitis B and C with a strong association with increasing age [

14]. In our study, we observed that both hepatitis B and C were more prevalent in age groups ranging from 30 to 45 years; this finding is also supported by other local studies reporting a high burden of HCV in the age group of 41-50 years. A study from Pakistan published in 2016 showed that hepatitis B and C have become more prevalent in younger age groups, which could be another public health concern in future [

17].

Hepatitis prevention and treatment in Pakistan is primarily carried out by provincial programs dedicated to hepatitis prevention and control. There is no national program in place. However, the Pakistan Health Research Council, which operates under the Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation, and Coordination, has coordinated a national response to hepatitis through a WHO Technical Advisory Group (TAG). The private sector also contributes significantly to hepatitis treatment in the country [

18]. To control the spread of these viruses, it is important to implement effective screening programs on a national level and increase awareness about the prevention and trans-mission of HBV and HCV. Early detection and treatment of these viruses can prevent severe liver diseases such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. Vaccination against HBV is also effective in preventing the spread of the virus.

In July 2019, on World Hepatitis Day, the Ministry of Health unveiled an ambitious program aimed at eliminating HCV and HBV by 2030. The program is focused on expanding prevention, testing, and treatment efforts via four provincial-level hepatitis programs, in addition to supplementing the existing National Hepatitis Strategic Framework 2017-2021 [

19]. Although the screening program in the present study is one step toward controlling the spread of these infections in the region, more efforts are required to increase awareness among the general population, particularly among migrants and refugees, regarding the risk factors, prevention, and treatment of hepatitis B and C infections. Moreover, the government should allocate more resources to improve the country’s healthcare facilities and ensure the provision of safe injections and blood transfusions.

4.1. Strengths

This was the first study to report the prevalence of hepatitis B and C among Afghanistan refugees. The sample size of this study was also greater than that of any other study done in the province. The screening program was entirely performed by a private hospital/institution involving free testing, free counselling, and free treatment of the patients. The aim of the screening program was not only to screen patients, but it was also a pilot initiative to pave the way for an elimination program that can be implemented on a national level for the elimination of hepatitis B and C within the country.

4.2. Limitations

This study was limited in that the screening program could not be extended to a provincial level involving multiple health centers for screening due to a lack of awareness among the population. Proper patient follow-up and treatment could not be completed due to the failure of the patients to report for follow-up, with the main reason being the Pak-Afghan border closure. Being a private-sector health facility, the number and diversity of visiting individuals were also low. The results of FibroScan, HBeAg, HBeAB, PCR, and ALT were beyond the scope of this study, as it only aimed to report the progress of the screening program. Unfortunately, the screening program was halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and a lack of funds.