1. Introduction

The environment of organizations is changing very rapidly. Organizations need to innovate, change, and transform quickly to meet the changing market expectations [

1]. Organizational innovation is essential to survive in various competitive conditions, such as those of accelerating technological development, globalization, and intensifying competition. Innovation is critical for driving organizational performance [

2] and is fundamental in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage in the business environment [

3]. Successful innovation enables a company to create exclusive products that enable premium strategies and further enhance their competitive advantage.

Many scholars have studied how to achieve innovation more efficiently and effectively and have emphasized the importance of entrepreneurship in achieving successful innovation outcomes [

4,

5,

6]. Entrepreneurship is an important factor in improving productivity and fostering economic growth, and CE facilitates the creation of new businesses through the creation of innovative products or processes, market development, and the adoption of strategic innovations [

1]. CE is a valuable strategy that can be adopted by any organization seeking to innovate and expand [

7] and it is a dynamic shift away from previous routines, strategies, business models, and operating environments in order to embrace new combinations of resources and make innovative proposals [

8].

Firms with a high CE intensity show an aggressive preference for maximizing profits, while firms with a low CE intensity adopt a ’wait-and-see’ strategy to minimize risk [

9,

10,

11]. According to Astrini et al.(2020), entrepreneurial firms are characterized by three well-known dimensions: (1) innovativeness in exploring new opportunities, (2) proactiveness in entering the market before their competitors, and (3) risk-taking when introducing new products [

12]. Entrepreneurship and innovation positively influence each other and interact to help organizations prosper [

13]. Entrepreneurship and innovation are complementary, and combining them well is essential for organizational success and sustainability in today’s dynamic and changing environment [

14]. Innovation is an essential choice for long-term competitive advantage and corporate survival, but it requires much time, effort, and money. As a result, it is difficult for individual companies to achieve IP through their own efforts alone.

Governments are increasingly utilizing a variety of policies to encourage companies to innovate and generate innovative outcomes. The most typical direct government intervention is to provide financial support such as R&D subsidies and tax incentives. However, in addition to direct financial or in-kind support, support can also be provided indirectly in the form of subsidies, such as those offered to consumers when purchasing certain products. According to the OECD, the main policy instruments used to support innovation include subsidies, capital support, borrowing support, capital support guarantees, payments for products and services, tax benefits, and access to infrastructure and services [

15]. In particular, the ratio of the Korean government’s R&D investment to the GDP was 4.9% in 2021, making it the highest among the OECD countries. That of the United States is at 3.5%, that of Japan is at 3.3%, and that of Germany is at 3.1%. With such large investments, there is an urgent need for empirical research on the effectiveness of government support. According to an OECD report, government support can effectively stimulate innovation and lead to economic growth.

The aim of this study was to provide empirical evidence of the factors affecting firms’ IP by conducting an empirical analysis of the relationships among CE, IP, and GS. Despite many researchers studying various aspects of CE and agreeing that enhancing CE contributes to firms’ performance and growth, there are few empirical studies on the effect of CE on IP. In addition, although governments in various countries have tried to improve firms’ performance by providing various forms of support, few studies have specifically identified the effectiveness of GS, and there are few comprehensive empirical studies on firms’ IP stratified by the type of GS. Consequently, this study, which specifically examines the moderating effect of GS on the relationship between CE and IP, will help improve governments’ efforts towards innovation.

This study empirically analyzed the relationships among CE, GS, and IP based on reliable survey data from the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STEPI). The dataset utilized in this study is that of the Korean Innovation Survey (KIS), which is an extensive and highly reliable source of information on manufacturing companies in Korea and is based on the Oslo Manual developed by the OECD and Eurostat. The Oslo Manual is an internationally recognized set of guidelines for collecting and interpreting data on the activities of innovation in different sectors of the economy. Based on data from the KIS, this study aimed to empirically verify the impact of CE on IP and the impact of GS on IP in 4,000 manufacturing firms in Korea, providing an important reference for the successful innovation performance of organizations. The research questions of this study were as follows.

RQ 1. Does CE have a significant effect on IP?

RQ 2. Does GS moderate the relationship between CE and IP?

The results of the study showed that all five factors of CE (innovativeness, risk-taking, proactivity, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness) positively affected IP. In addition, the moderating effects of seven types of GS (tax incentives, subsidies, financial support, human resource support, technical support, certification support, and procurement support) were validated, and it was found that five types of GS, namely, tax incentives, subsidies, human resource support, certification support, and procurement support moderated the relationship between CE and IP. The results also showed that the indirect effects of GS on IP were different, depending on the characteristics of individual firms’ CE.

The results of this study provide important evidence for the strengthening of CE and the provision of various types of GS to improve firms’ IP. When implementing support policies, the entrepreneurial characteristics of firms should be considered for the selection of target firms and the strengthening of support policies to match the firms’ characteristics, so that IP can be more effectively improved. As innovation policies are vital for supporting economic growth and improving competitiveness, governments should utilize various policies to help promote firms’ innovation activities and generate innovative performance. This study will contribute to the formulation of specific governmental support strategies.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Corporate Entrepreneurship (CE) and Innovation Performance (IP)

Innovation is the implementation of new or significantly improved products or processes, new marketing methods, and new organizational methods in business practices, in the organization of the workplace, or in external relations [

16]. Innovation is also an important function of entrepreneurship that enables entrepreneurs to create new wealth-creating resources or enhance existing resources [

17,

18]. It involves transforming novel and imaginative ideas into tangible outcomes, such as by creating new products or services, integrating disparate concepts in new ways, finding new uses for existing resources, and moving existing ideas into new contexts [

19].

According to Drucker (2002), innovation is "a specific function of entrepreneurship, how entrepreneurs create new wealth-creating resources or endow existing resources with enhanced potential to create wealth" [

17]. Van de Ven (2017) defined innovation as the development and implementation of new ideas over time by people engaged in transactions with others within an institutional order [

20]. By utilizing innovation, entrepreneurs can enhance their competitiveness and create value for stakeholders, including customers, employees, and investors. Innovation is an essential component of corporate success, and managing it effectively is critical for sustaining long-term growth and profitability.

Chaithanapat et al. (2022) emphasized the pivotal role of innovation in shaping organizational performance [

2]. Improvements in organizational effectiveness through innovation are more pronounced among individuals who are quick to embrace advancement than among those who resist change [

3]. Hence, innovation is fundamental to achieving a sustainable competitive advantage in the business environment. It is important to recognize that a successful innovation process can be a real source of competitive differentiation, as it enables premium pricing strategies by providing exclusive offers that are not available in a competitive environment. Furthermore, given that a successful process of innovation that introduces new products contributes to establishing and strengthening a competitive advantage, modern innovative organizations not only leverage innovation to generate these advantages, but also exert dominance and outperform market leaders within the industries that they re-enter [

21].

Innovation capability refers to a firm’s ability to successfully introduce and adapt new ideas into products, services, and processes [

2], and its ability to explore new opportunities or devise new solutions to given problems [

23]. Furthermore, innovation capability is a comprehensive set of assets encompassing technology, products, processes, knowledge, experience, organizations, and others that support and foster a firm’s technological innovation strategy [

24]. It is an important resource that ensures sustainable success by supporting and fostering a firm’s innovation strategy and is an important outcome of innovation activities [

25]. Since innovation activities begin with an understanding of the organization’s internal environment to build core competencies, inter-firm differences in innovation activities are associated with specific resources, that ultimately enhance a firm’s competitiveness [

26].

Innovation capability is an important determinant of innovation performance [

27,

28]. As a result of innovation capability, innovative products are more appealing to customers, which affects a firm’s competitive advantage [

29] and increases revenue generation through innovation performance [

30]. This study examined the effects of CE on IP. According to the literature, innovation performance (IP) is defined as the development of new or significantly improved products or services over existing products or services.

In the traditional context, entrepreneurship has functioned as a tool for identifying and capturing opportunities in technological innovation [

31] and has contributed positively to both technology-driven and market-driven innovation [

32]. With the revitalization of venture capital in the mid-20th century, entrepreneurship was propagated as a tool for enhancing corporate competitiveness, which became a driving force for maintaining and growing the dynamism of market economies [

33]. Early research on entrepreneurship focused primarily on startup venture founders, but as organizations matured, the scope of research expanded beyond individual participants, such as entrepreneurs and key decision-makers, to encompass entire firms [

34]. As society has evolved into a knowledge-based economy, entrepreneurship is recognized as a source of competitive advantages, such as corporate innovation, learning, and environmental adaptability [

35]. Emphasizing the process of technological innovation within technology-driven firms, technology entrepreneurship represents "a style of corporate leadership that identifies technology business opportunities with high-growth potential through principles-based decision-making, mobilizes the necessary people and capital, and systematically manages the significant risks associated with rapid growth" [

36]. It also operates as "a mechanism for creating new resource combinations and integrating technical and commercial domains in a profitable way to realize technological innovation" [

37].

Stam (2013) defined intrapreneurship or entrepreneurial employee activities as the development of new business activities by employees, and they followed a bottom-up approach [

38,

39]. CE, on the other hand, can be seen as a decision initiated by top management, that is then realized at lower levels of an organization. CE refers to entrepreneurship behaviors that occur within an organization [

40] and includes a variety of activities such as organizational improvement, innovation, and new venture creation; these activities affect the organization’s survival, growth, and performance [

41,

42]. The definition of CE has evolved over time, and various definitions have emerged [

43]. One of the most widely used definitions is that of Sharma and Chrisman (1999). According to Sharma and Chrisman (1999), CE is the process by which individuals or some group of individuals within an existing organization create a new organization or bring about innovation or improvement within that organization [

44]. CE is referred to with various terms such as internal entrepreneurship [

45], internal corporate venturing [

46], corporate venturing [

47,

48], and intrapreneurship [

4], and CE and intrapreneurship are sometimes used interchangeably. Similar terms include organizational entrepreneurship, corporate venturing, and strategic entrepreneurship [

49,

50].

Recent research on CE has focused on how firms create new businesses to deliver new returns and value for shareholders [

51], and in both the academic and practical domains, it is widely acknowledged as a valid pathway toward improving organizational performance [

52]. Entrepreneurship is closely linked to a firm’s ability to operate or utilize its resources [

53,

54], and the efficiency of and capacity for resource utilization depend on the intensity of entrepreneurship [

55]. Firms exhibiting a high intensity of entrepreneurship actively develop new products [

56], and a higher intensity of entrepreneurship enhances technological innovation performance [

57,

58,

59].

The reason for why companies need to strategically strengthen CE is that change, innovation, and improvement are needed in the market to avoid stagnation and downturn, and it can be used to overcome weaknesses in current corporate management methods and solve problems such as employee turnover due to dissatisfaction with bureaucratic organizations[

4,

5]. In general, CE can take many forms, such as continuous regeneration, organizational rejuvenation, strategic renewal, or territorial redefinition. Organizations that undertake CE are perceived as dynamic and flexible, and they are able to catch new opportunities as they arise [

6]. These organizations accept risk and acknowledge that the outcomes of innovation are uncertain [

60]. Building on the literature, corporate entrepreneurship (CE) was defined in this study as the active effort of an organization to take risks, create new businesses, and stimulate innovation and change.

According to the various definitions of CE, in essence, it is an important driver of innovation. Entrepreneurship has become an integral part of the innovation ecosystem at both the individual and corporate levels [

61]. Companies today make various policies to enhance entrepreneurship [

62], and waves of entrepreneurship have been witnessed in many organizations [

63]. Although entrepreneurship and innovation performance are highly interdependent, there is a lack of empirical research that clearly supports this relationship [

64,

65,

66]. Accordingly, in this study, CE will be a positive effect on IP and this study establishes the following hypotheses to validate it.

H 1. CE has a positive effect on IP.

H 1-1. Innovativeness has a positive effect on IP.

H 1-2. Risk-taking has a positive effect on IP.

H 1-3. Proactiveness has a positive effect on IP.

H 1-4. Autonomy has a positive effect on IP.

H 1-5. Competitive aggressiveness has a positive effect on IP.

2.2. Government Support (GS) and Innovation Performance (IP)

Striving for IP involves not only individual companies but also governments. There are many difficulties in achieving IP through the efforts of individual companies alone, and institutional and financial support from governments helps companies achieve IP. Previous studies have shown that GS in the form of public policy instruments is highly correlated with private R&D expenditure and IP [

67,

68], and R&D expenditure is known to stimulate IP [

69,

70].

Government support programs include direct and indirect financial transfers to firms, which can be in the form of financial assistance or in-kind contributions. They can also be provided directly or indirectly, such as through subsidies offered to consumers when purchasing certain products. Public support intended to benefit businesses can target business activities or their results. Methods of categorizing government policy instruments include classifying them according to the objective of the support provided for innovation capacity or innovation activities, policy objectives, the type of instrument, the level of the responsible government agency, any conditions of the support, and the monetary value of the support [

15].

According to the OECD’s Frascati Manual (2015), the main policy instruments for supporting innovation include subsidies, equity finance, debt finance, equity finance guarantees, payments for products and services, tax incentives, and access to infrastructure and services [

15]. A subsidy is a government grant or transfer of funds for innovation activities that are typically related to a specific innovation project, to help cover the associated costs. Equity financing is when the government invests in the equity of a company. Debt financing refers to the government providing loans for innovation activities, and equity financing guarantees refer to the government providing guarantees to induce third-party investment in an enterprise’s innovation activities. Payments for products and services are purchases of products or services from a business that implicitly or explicitly require innovation as part of the payment agreement. Tax incentives are provided for R&D expenditures or innovation performance systems related to innovation activities and outcomes. Finally, there are policies that directly or indirectly provide infrastructure and services for firms’ innovation activities.

The most representative way in which the Korean government directly intervenes to support corporate R&D investment is by providing financial support, which is typically in the form of R&D subsidies or tax incentives for firms [

71]. Other types of support include start-up support, technical support, sales and marketing support, and human resource support [

72]. GS is designed not only to encourage firms to invest in innovation, but also to promote collaborative activities between firms and other organizations [

74]. Guellec and Potterie (2003) found that GS for R&D had a positive effect on firms’ R&D investment, and Hinloopen (2000) pointed out that government support policies can be implemented to encourage firms to form collaborative networks, but there is a lack of analysis of this aspect [

74,

75].

The literature on GS and IP in Korea includes the following. Jeon and Yoon (2011) found that R&D funding, expanded participation in national projects and that support for collaborative activities among the industry, academia, and research centers affected firms’ IP [

76]. Binh and Park (2017) analyzed the effects of financial support policies for SMEs and found that government support promoted firms’ external growth but made a weak contribution to improving profitability [

77]. Yang et al. (2015) found that GS indirectly enhanced firms’ export performance by strengthening their internal capabilities [

78]. Seo and Lee (2007) found a moderating effect of government R&D support systems on the level of technology management in SMEs [

79]. Choi (2015) argued that GS for technological development expands internal R&D investment, and GS for technology development, technical support, and the development of human resources strengthens R&D cooperation [

80].

Jeon and Nam (2019) examined the impacts of research and human resource development support systems on technological innovation performance and the mediating effect of entrepreneurship in this relationship for SMEs, and they found that research and human resource development support systems generally have a positive impact on technological innovation performance [

81]. Lee et al. (2013) found that GS for technological development had a significant positive effect on the IP of SMEs [

82]. Suh (2018) empirically analyzed the type of impact of financial support from the government and private financing on the technological innovation performance of domestic venture firms and found that financial support from the government positively mediated technological innovation performance by using differentiated cooperation networks with external cooperation partners, thus confirming the relationship between the utilization of the governmental support system and IP [

83].

Various prior research studies confirmed the significant relationship between GS and IP. However, few studies have analyzed the impact of specific government support systems, and none have explored the relationships among CE, GS, and IP. Hence, this study aimed to analyze the effects of GS on the relationship between CE and IP by formulating the following hypothesis.

H 2. GS positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

In this study, KIS data were used to investigate GS by using relevant questionnaire items. By using the KIS data, the moderating effects of each of the seven government support systems (tax support, subsidies, financial support, human resource support, technical support, certification support, and procurement support) were examined. The sub-hypotheses were as follows.

H 2-1. Tax support positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

H 2-2. Subsidies positively moderate the relationship between CE and IP.

H 2-3. Financial support positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

H 2-4. Human resource support positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

H 2-5. Technical support positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

H 2-6. Certification support positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

H 2-7. Procurement support positively moderates the relationship between CE and IP.

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Model

This study aimed to empirically verify the effect of CE on IP and the moderating effect of GS.

Figure 1 shows the research model.

3.2. Variables

Several dimensions of CE can be found in the literature. Ferreira (2010) researched the antecedents of entrepreneurship and emphasized the importance of entrepreneurship at the firm level. He suggested that entrepreneurship interacts with individual, organizational, and environmental factors, as well as a firm’s performance and growth, and proposed a strategic orientation consisting of risk-taking, innovativeness, proactivity, and autonomy [

84]. Li et al. (2012) conducted a study on entrepreneurial orientation in international markets and proposed the definition of entrepreneurial orientation as innovativeness, proactivity, and risk-taking [

85]. They studied the effects on international scope and found that greater innovativeness and proactivity increased international scope, while the opposite result was found for risk-taking [

85].

Linton (2019) investigated how the attributes of the processes and outcomes of the entrepreneurial orientation (EO) dimension interacted with each other by conducting a longitudinal study over two years [

86]. The study proposed innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactivity as the subdimensions of EO, and it argued that each sub-dimension should be separated into process and outcome components [

86]. Astrini et al. (2020) measured the intensity of CE by using innovativeness, proactivity, and risk-taking in four SMEs in Indonesia. The results showed that all four SMEs had low to moderate CE intensity [

87]. Al-Mamary and Alshallaqi (2022) researched the impact of EO on entrepreneurial intentions, categorizing aspects of EO into autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactivity, and competitive aggressiveness. The results showed strong correlations among autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactivity, and entrepreneurial intentions [

88].

The KIS data used in this study categorize aspects of CE into innovativeness, risk-taking, proactivity, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness. Beyond individual dispositions, as an organizational culture, CE enhances a company’s innovativeness, causes the risk of change to be accepted, and involves actively striving to pre-empt the market ahead of competitors. Moreover, the types of GS were categorized into taxation support, subsidies, financial support, human resource support, technical support, certification support, and procurement support.

CE was measured by using a scale from 1 to 7. For example, innovativeness was measured on a scale from 1 (stable and established business procedures) to 7 (business procedures that pursue change and innovation). GS was measured on a scale of 1 (very low) to 5 (very high), with 0 for "not utilized". The dependent variable, IP, was measured according to whether new products or services were developed. The operational definitions of the variables used in this study are shown in

Table 1.

3.3 Research Data

This study used data from the 2020 Korean Innovation Survey (KIS) provided by the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STEPI). The KIS is a nationally approved statistical survey (approval number: 395001) conducted and analyzed by the STEPI to continuously assess the status of innovation and the characteristics of domestic firms. Based on the OECD’s Oslo Manual, an international guideline for surveys on innovation, the KIS was designed and implemented to allow international comparisons by using a representative statistical survey of innovation activity at the enterprise level.

In this study, the KIS data were used to analyze 4000 manufacturing firms while focusing on 16 items covering CE, IP, GS, and general characteristics of the firms. The analysis was conducted in a manner suitable for publication in academic management journals.

Table 2 shows the general characteristics of the data used in this study. Of the 4000 manufacturing firms used in this study, 3451 had fewer than 300 employees, making up about 86% of the sample. This reflects a characteristic of Korean firms—the number of small and medium-sized enterprises is quite high compared with the number of companies. The number of companies in the sample that were in the national industrial complex was 947, which was about 24% of the sample, and the numbers of companies listed on the KOSPI, KOSDAQ, and KONEX were 259, 328, and 14, respectively, making up about 15% of the sample, while 85% of the 3399 companies were unlisted.

4. Results

The analysis was conducted according to the general procedure of empirical research by using the SPSS 26.0 software. To validate the moderating effect, the SPSS process macro 4.1 was additionally installed to analyze by using model 1. The results of this study provided in following.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables

The descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study are shown in

Table 3. The five factors of CE were distributed from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 7, with mean values of 3.12, 2.90, 3.69, 3.75, 4.01, and 1.21 for innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness, respectively. In the case of GS, the average was very low because it included 0, which indicated no support from the government. For each factor, there were 1407 firms receiving tax support, 728 firms receiving subsidies, 594 firms receiving financial support, 548 firms receiving human resource support, 698 firms receiving technical support, 1021 firms receiving certification support, and 444 firms receiving procurement support. There was a difference in the average value according to the type of GS.

4.2. Correlations Analysis

The results of the correlation analysis showed that, among the factors of CE, the correlation between risk-taking and innovativeness was the highest at 0.689, while among the types of government support, the correlation between funding and risk-taking was the lowest at 0.020. Each factor of CE and CS was found to be significantly correlated with IP at the 95% significance level. The results of the correlation analysis of the 13 variables used in this study are shown in

Table 4. This study analyzed the existing data and did not undertake a factor analysis because the KIS used a single-factor questionnaire.

4.3. Results of Analyzing the Effects of CE on IP

The effects of five factors of CE on IP were analyzed according to the research model. 0The analysis was conducted by using two-stage logistic regression, and the results are shown in

Table 5.

The results showed that these five factors of CE, namely, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactivity, autonomy, and competitive aggressiveness, were significant at the significance level of 0.01, and autonomy was significant at the significance level of 0.05. The upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals were also found to not include 0 in each case, indicating that the effect of CE on IP was statistically significant. Accordingly, Hypothesis 1, which states that CE has a positive effect on IP, was confirmed.

The odds ratios for the five factors of CE were 1.263 for innovativeness, 1.225 for risk-taking, 1.209 for proactivity, 1.064 for autonomy, and 1.373 for competitive aggression, indicating that an increase in CE increased innovation performance. For example, this meant that for every one-point increase in innovativeness, IP improved by 1.263 points. In order of the effect of CE on IP, competitive aggressiveness had the greatest effect, followed by innovativeness, risk-taking, proactivity, and autonomy. Competitive aggressiveness is the tendency to prioritize market advantage over other competitors in a changing environment. Thus, competitive aggressiveness, which is a firm’s tendency to develop new products or services to gain an advantage over competitors, was found to have a strong positive effect. In addition, innovativeness refers to the degree of acceptance of change and innovation in business processes, so firms with high innovativeness have a strong tendency towards the rapid development of new products, which is important for achieving innovative performance.

4.4. Moderating Effects of Government Support on CE and IP

This study conducted a logistic regression analysis with CE as the independent variable, IP as the independent variable, and GS as a moderating variable to determine the effect of GS on the relationship between CE and IP. For each of the seven factors of GS, the moderating effect was verified by integrating the five factors of CE, and the moderating effect of each of the five factors was verified. The SPSS macro 4.1 developed by Hayes (2013) was utilized for the moderation analysis, with a significance level of 0.05 and 5000 bootstrap samples.

4.1.1. Moderating Effect of Tax Support on CE and IP

The indirect effect of tax support on CE and IP showed that the effect of CE on IP was strengthened as the government’s tax support increased.

Table 6 shows the effect of tax support by integrating the five factors of CE into one variable. There was no 0 between the LLCI and ULCI in the interaction term of CE and GS_tax, which meant that the indirect effect was significant. The Z-value of the interaction term between CE and GS_tax was 2.998 at the 0.01 level of significance, and the correlation coefficient was 0.060. Hypothesis 2-1—stating that tax support moderates the relationship between CE and IP—was, thus, supported.

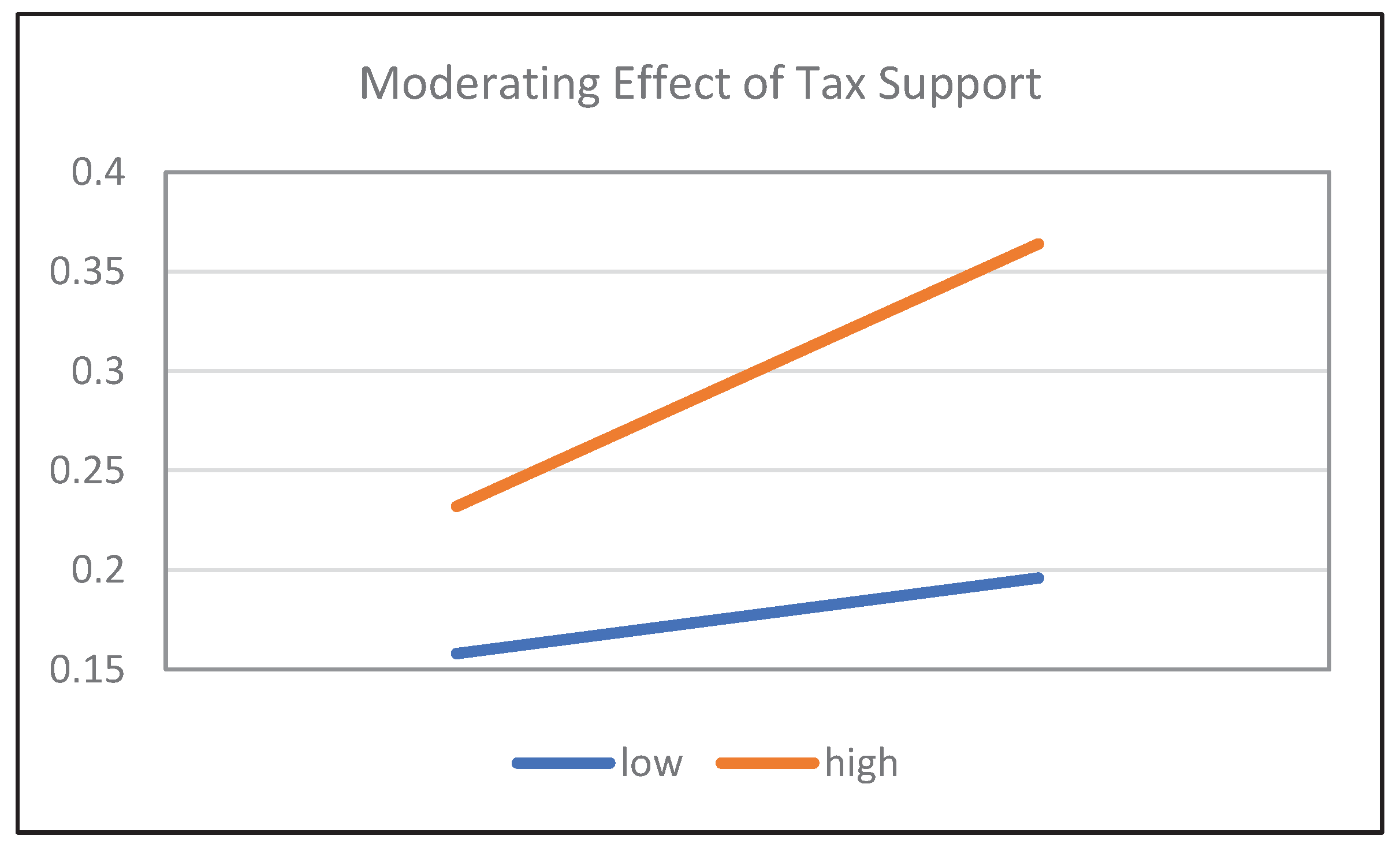

A visualization of the moderating effect of tax support on the relationship between CE and IP is shown in

Figure 2. The slope is steeper for those with above-average tax support than the slope for those with below-average tax support. The greater the tax support, the stronger the effect of CE on IP.

The moderating effects of tax support on each of the five dimensions of CE are shown in

Table 7. Innovativeness and risk-taking were found to strengthen the relationship between CE and IP at the 0.01 level of significance, while proactiveness, autonomy, and competitiveness aggressive were not statistically significant.

4.1.2. Moderating Effect of Subsidies on CE and IP

Next, the moderating effect of subsidies on CE and IP was validated. After analyzing the five factors of CE together, the results showed that the moderating effect of subsidies was significant. The results are shown in

Table 8. Subsides significantly strengthened the effect of CE on IP. Hypothesis 2-2, which states that subsidies moderate the relationship between CE and IP, was supported.

The results show that the effect of CE on IP increased as the level of subsidies increased, as visualized in

Figure 3. The slope of the group with a higher-than-average subsidy was steeper than the slope of the group with a lower-than-average subsidy, which meant that the effect of CE on IP was strengthened as subsidies increased.

Table 9 show the effects of subsidies on each of the five factors of CE, which were the independent variables. The results showed that risk-taking, proactiveness and competitive aggressiveness strengthened the relationship between CE and IP. However, no statistical significance was found for innovativeness and autonomy.

4.1.3. Moderating Effect of Financial Support on CE and IP

The moderating effect of financial support on CE and IP was analyzed. The integrated analysis of the five factors of CE showed that the interaction term between the moderating variable, financial support, and the independent variable, CE, was not statistically significant. The results of the analysis are shown in

Table 10. Thus, Hypothesis 2-3—stating that financial support moderates the relationship between CE and IP—was rejected.

The results of the analysis of each of the five factors of CE in terms of the effects of financial support on CE and IP are presented in

Table 11. The results of the combined analysis of the five factors were not significant, but the analysis of each factor showed that innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness had an indirect effect on CE and IP, but the correlation coefficient was negative.

4.1.4. Moderating Effect of Human Resource Support on CE and IP

The results of the analysis for the verification of the effect of human resource support on CE and innovation performance among the types of government support were as follows.

Table 12 shows the results of integrating the five factors of CE into one variable to analyze the effects of financial support, and the analysis showed that human resource support strengthened the effects of CE on IP. As human resource support increased, the impact of CE on IP increases. Accordingly, Hypothesis 2-4—stating that human resource support moderates the relationship between CE and IP—was supported.

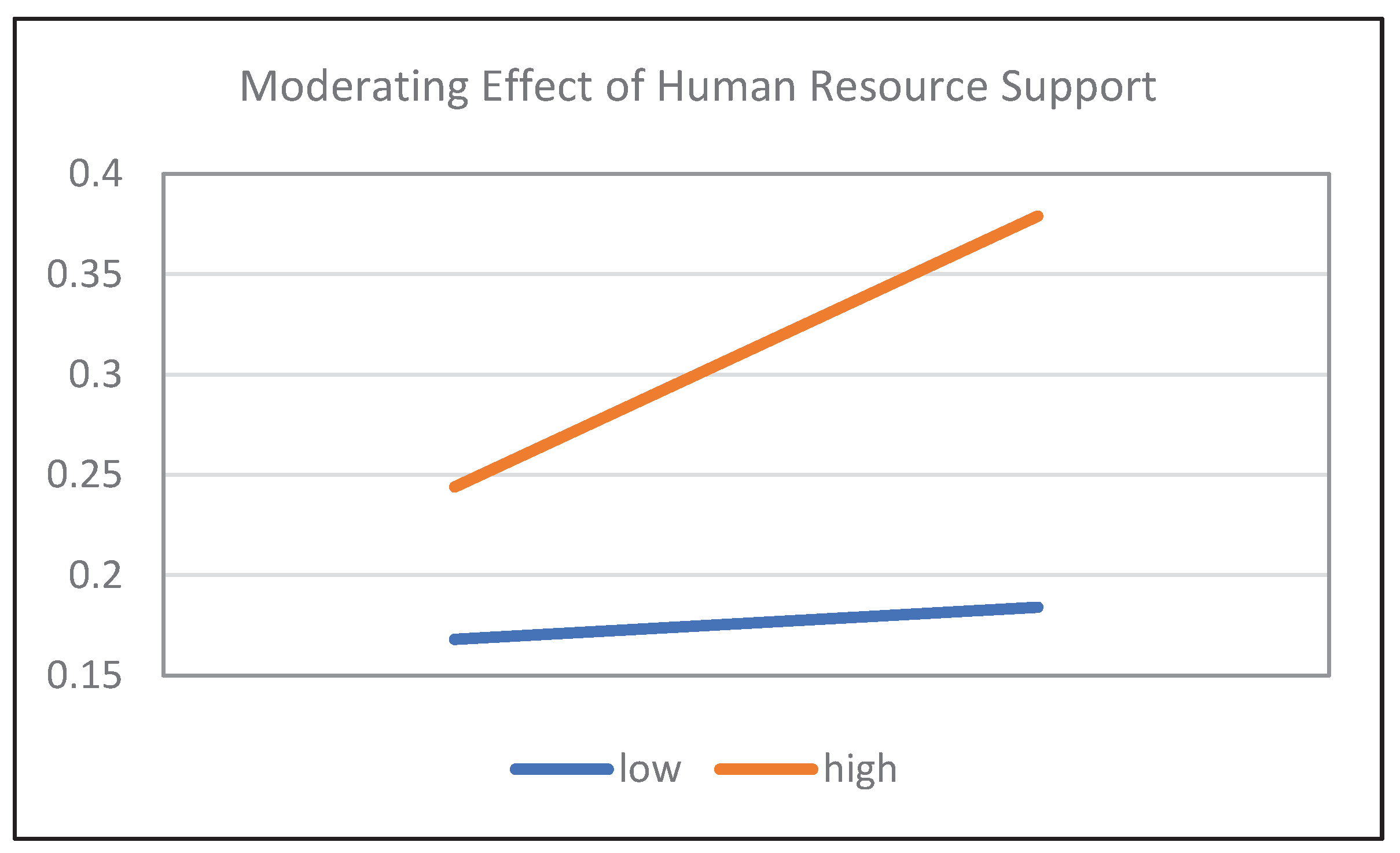

Comparison of the slopes of the effect of human resource support for the below-average and above-average groups showed that there was an increase in steepness of more than twofold, which meant that the effect of CE on IP became stronger as human resource support increased. A visualization of this is shown in

Figure 4.

In addition, the effect of human resource support on each of the five factors of CE, the independent variable, is shown in

Table 13. The correlation coefficients of the interaction terms for the four factors other than autonomy were significant.

4.1.5. Moderating Effect of Technical Support on CE and IP

The results of the analysis for the verification of the effect of technical support on CE and IP were as follows. There is a zero between the LLCI and ULCI in the interaction term of CE and technical assistance, and the Z-value was not statistically significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2-5—stating that technical assistance moderates the relationship between CE and IP—was rejected. The results of the analysis are shown in

Table 14.

The effects of technical support on each of the five factors of CE, which were the independent variables, were also analyzed (

Table 15). In the case of technical support, there were no indirect effects on any of the five factors of CE.

4.1.6. Moderating Effect of Certification Support on CE and IP

The results of the analysis for the verification of the effect of certification support on CE and IP are shown in

Table 16. The results meant indicated that certification support had a moderating effect on the relationship between CE and IP. Hence, Hypothesis 2-6 is supported.

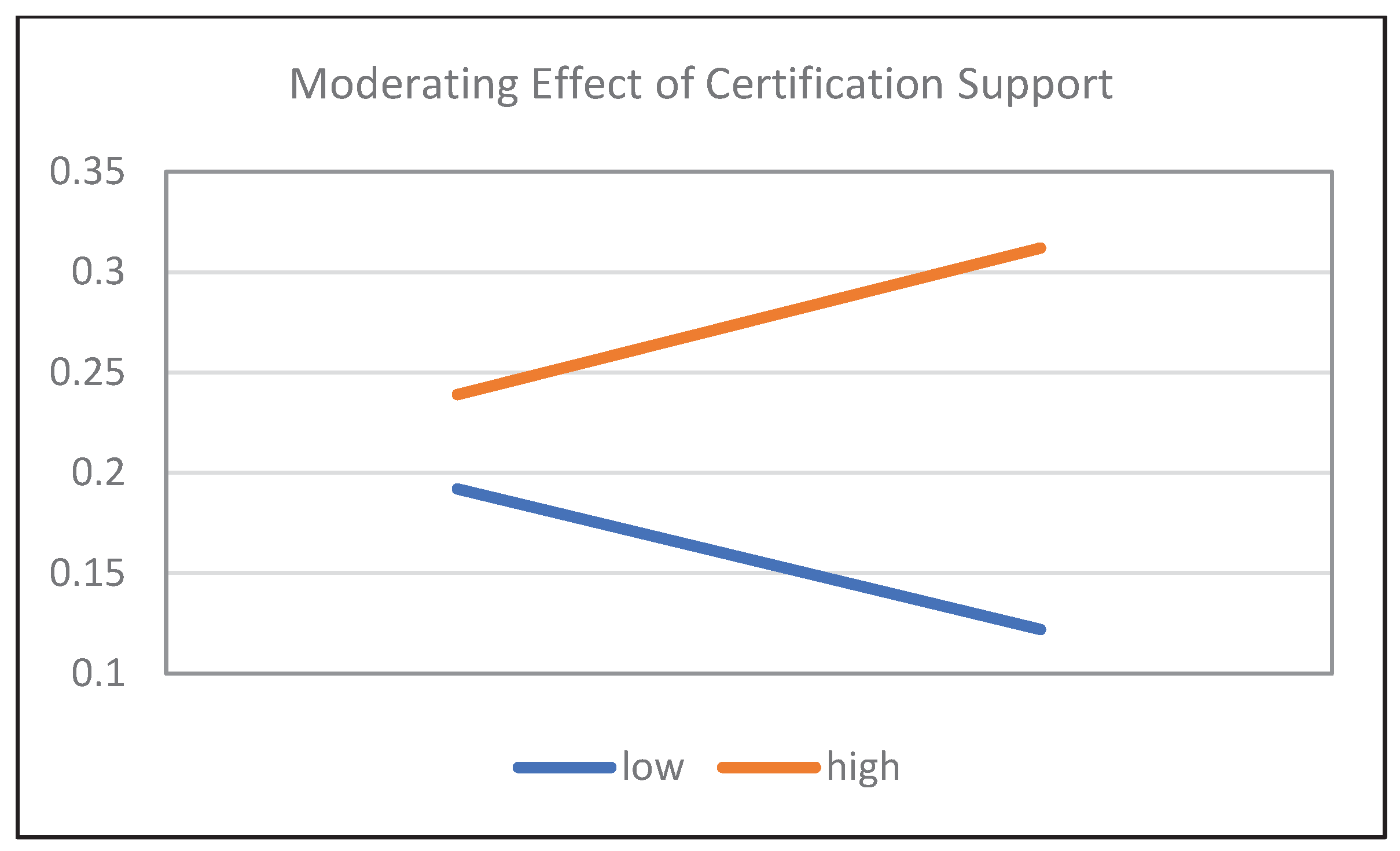

The effect of CE on IP was significantly greater in the higher-than-average group than in the lower-than-average group. When certification support was lower-than-average, the effect of CE on IP was mitigated as certification support increased, and when certification support was higher-than-average, the effect of CE on IP was increased. A visualization of the moderating effects of certification support is shown in

Figure 5.

The moderating effects of certification support on each of the five factors of CE, which were the independent variables, is shown in

Table 17. Certification support had a moderating effect on all five dimensions of CE.

4.1.7. Moderating Effect of Procurement Support on CE and IP

Finally, the results of the analysis for determining the effect of procurement support on CE and IP are shown in

Table 18. The interaction term between CE and procurement support was statistically significant, indicating that procurement support moderated the effect of CE on IP. Accordingly, Hypothesis 2-7 was supported.

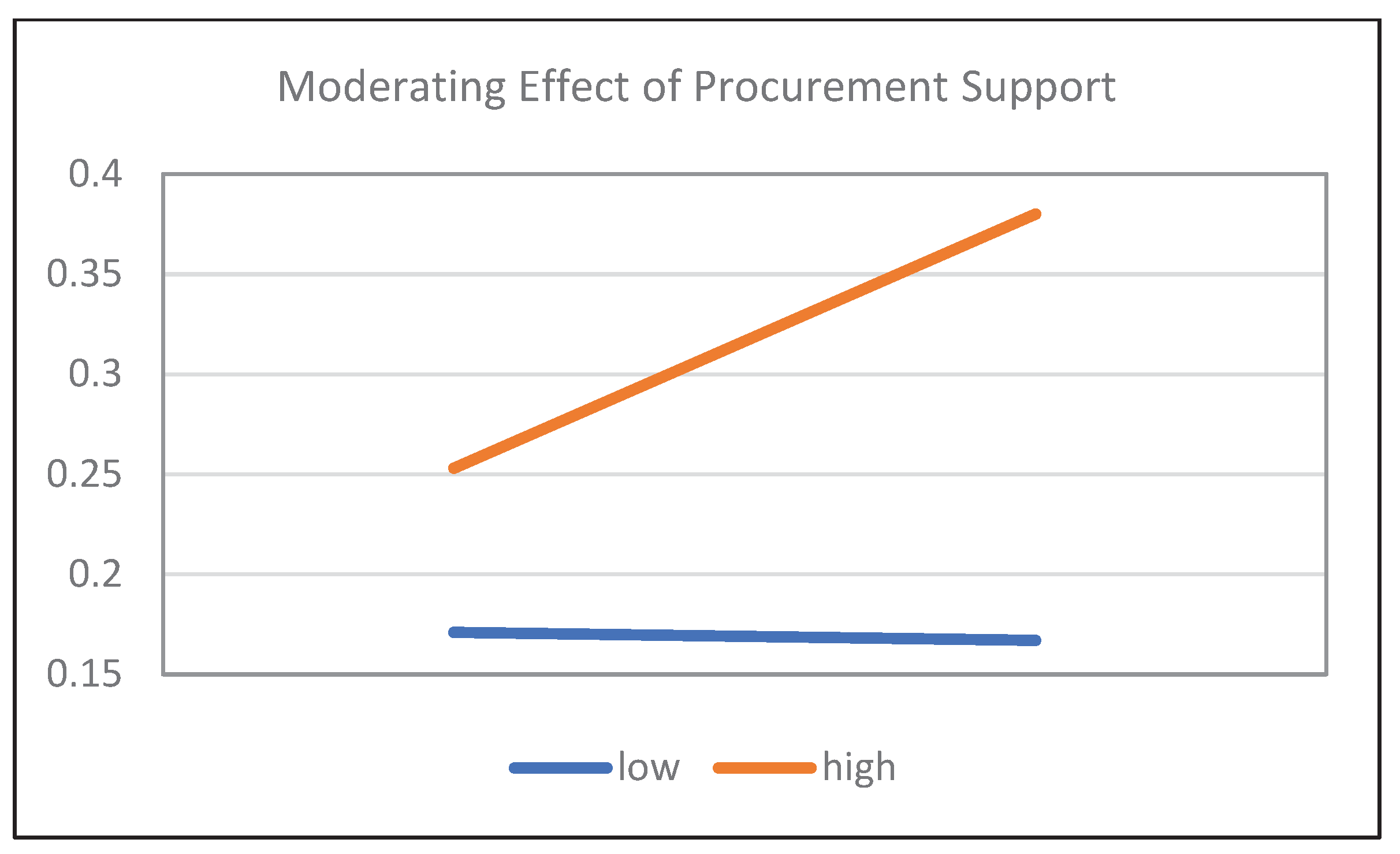

The effect of CE on IP was significantly higher in the group with higher-than-average procurement support than in the group with lower-than-average procurement support. A visualization of the moderating effect of procurement support on CE and IP is shown in

Figure 5. The slope was particularly steep for the group with higher-than-average procurement support.

Furthermore, the effects of procurement support on each of the five dimensions of CE, which were used as independent variables, were analyzed (

Table 19). Procurement support moderated the effects of innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness on CE, but not autonomy.

5. Discussion

As the first step in empirical research, this study examined the effect of CE on IP. Compared with previous studies that used limited CE, this study found that all five factors of organizational entrepreneurship (innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy, and competitiveness) used in the KIS data from the STEPI, a research institute of the Korean government, contributed positively to IP. While most previous studies [

12,

89] used and validated some of these factors as part of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) this study used five variables of EO based on extensive and authoritative data from Korean research institutes. The five variables of CE proposed by the STEPI were validated as appropriate variables. The five variables can be actively used in subsequent studies that involve data on Korean manufacturing firms.

Based on the finding that GS affects firms’ innovativeness, this was the first empirical study to verify the moderating effect of GS on firms’ innovativeness. While studies on corporate IP, such as R&D investment and support for technical development, which are representative government support programs, have shown conflicting results, and government support programs have been used as a limited independent variable [

76,

78,

79], this study uses all seven variables of the currently used government support programs to test their moderating effects regardless of firms’ size. In the research model, government support was an exogenous variable, not an autonomous decision variable that firms could decide on for themselves, so it was logical and appropriate to use it as a moderating variable.

Table 20 summarizes the results of the analysis of the moderating effect of GS.

Excluding financial support and technical support, five government support programs, namely, tax support, funding, human resource support, certification support, and procurement support, were found to be moderating factors affecting innovation performance. The results showed that tax support, financial support, and human resource support had a reinforcing effect, meaning that the impact of CE on IP increased as the support increased. In the case of certification support and procurement support, the effect of CE on IP decreased in the group with lower-than-average support and increased in the group with higher-than-average support. The findings of the strengthening and interference effects among the moderating effects are valuable for managers in charge of government support. In the case of certification support, certification procedures such as corporate certification and technical/performance certification affect performance when the certification is finally completed. Therefore, it can be interpreted that if support is not fully utilized, it does not have a positive effect on performance. In addition, in the case of procurement support, the outcome can be in the form of, for example, public procurement and designations as excellent products. Therefore, if the support system is partially utilized, but the outcome is not achieved, it does not have a positive effect on performance. The effect of CE on IP significantly increased for companies that actively utilized certification support and procurement support.

On the other hand, the moderating effects of financial and technical support were not significant. Technical support includes technological development, commercialization of technology, technology transfer, patent strategies, and the construction of infrastructure. It was inferred that the moderating effect of technical support on innovation performance was not significant because firms with high entrepreneurship are more likely to have their own technology and, thus can utilize the existing technology to improve their innovation performance. Moreover, financial support refers to investments, loans, assistance for financing technology, and guarantees, but unlike subsidies, such as those for participation in national R&D projects, this did not show a significant effect on the effect of CE on innovation performance. This result indicated that, as with technical support, highly entrepreneurial firms are more influenced by institutional support for the mass production of new products and services than by support for sourcing technologies.

The moderating effects of the seven types of government support were analyzed in detail for each of the five factors of CE, and moderating effects were found for five items of certification support, four items of human resource support and procurement support, three items of funding and financial support, and two items of tax support. The effectiveness of government support on the impact of CE on IP was greatest for certification support, human resource support, and procurement support. In the case of highly entrepreneurial firms, it is more effective to provide additional support for commercializing a technology than to provide support for the original technology itself. Therefore, it can be concluded that enhancing such support is more effective in improving innovation in highly entrepreneurial firms.

In a comparison of the moderating effects of each item of CE, it was shown that there were significant moderating effects for six items of risk-taking, five items of innovation and proactivity, and four items of competitive aggressiveness. In the case of autonomy, however, no significant moderating effects were obtained for all types of GS, except for certification support. Autonomy had a positive effect on IP in that it emphasizes employees’ effort and empowerment, but it did not have a significant effect on the effectiveness of GS. Thus, to increase the effectiveness of GS, it is necessary to select firms with high levels of risk-taking, innovation, proactivity, and competitive aggressiveness when they apply for support, or to establish institutional mechanisms such as training and evaluation items, for enhancing entrepreneurship.

This study resulted in the significant finding that various GS measures improve IP, and the effects were specifically tested according to the five dimensions of CE. To contribute more to the improvement of the IP of organizations, it would be more effective to identify the entrepreneurship of companies and accordingly provide support. Many studies have discussed the effectiveness of GS by focusing on the outcomes of specific support measures or financial performance. However, the results of this study, which showed that several types of GS strengthen the effects of CE on IP, provide meaningful evidence of the importance of continuous and diverse forms of GS. While innovation can be achieved through individual organizational efforts, various types of institutional support from the government can contribute to higher innovation performance across all dimensions. This provides empirical support for the important finding that government support programs can improve firms’ IP and increase their sustainability.

Based on this study, subsequent can be carried out. First, a longitudinal study of manufacturing firms’ innovation performance is suggested. The Korean government is currently collecting data on innovativeness in manufacturing based on the Oslo Manual on an ongoing basis. Therefore, a direct comparative study may not be possible, but a comparative empirical study based on Korean manufacturing firms and the Oslo Manual could be conducted to verify differences among countries. In addition to a cross-sectional study of manufacturing firms, the discovery of significant variables through a longitudinal study based on long-term data could be a new research direction.

Second, a study by firm size based on this research model is suggested. This study did not conduct a test of differences by company size to validate the research model. In the future, it would be useful to empirically verify whether there is a difference in this research model by firm size to help policy-makers create government support programs that effectively differentiate to optimize the efficient use of government resources and performance.

6. Conclusions

Many organizations strive to survive in a world of constant change. The reason for why organizations strive to innovate is survival. Proactively accepting change in a changing society and driving efforts to stay ahead of competitors leads to business growth and increased sustainability. Innovation and entrepreneurial organization have become commonplace in corporate competitiveness. Organizations strive to secure sustainability and self-sustainability on their own, but to help them survive in the global market, governments are considering and providing various appropriate support measures. When the efforts of individual companies are combined with the active and extensive support of governments, the results of innovation can be synergized. It is impossible to adapt to new changes without the willingness to take risks. CE involves change and is a characteristic of an organization, not just the efforts of a few individuals. The results of this study showed that CE should not be limited to the founders of startups or ventures but should be embedded in the culture of entire organizations, including large corporations. This study also provided evidence that governments can make a significant contribution to improving the innovation performance of companies by operating and supporting appropriate systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. Y. and S. H.; methodology, J. Y. and S. H.; software, S. H.; validation, J. Y. and S. H.; writing—original draft preparation, S. H..; writing—review and editing, J. Y.; visualization, S. H.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study used the Korean Innovation Survey (KIS) data provided by the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STEPI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tseng, C.; Tseng, C. C. Corporate entrepreneurship as a strategic approach for internal innovation performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2019, 13, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithanapat, P.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Oo, N. C. K. K.; Rakthin, S. Relationships among knowledge-oriented leadership, customer knowledge management, innovation quality and firm performance in SMEs. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2022, 7, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, R. T.; Alhaidan, H.; Al Halbusi, H.; Al-Swidi, A. K. Do organizations really evolve? The critical link between organizational culture and organizational innovation toward organizational effectiveness: Pivotal role of organizational resistance. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2022, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D. F.; Montagno, R. V.; Hornsby, J. S. Developing an intrapreneurial assessment instrument for an effective corporate entrepreneurial environment. Strategic management journal 1990, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J. Corporate entrepreneurship: A strategic and structural perspective. In International Council for Small Business 2002, 47, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G. G.; Ireland, R. D.; Zahra, S. A.; Floyd, S. W.; Janney, J. J.; Lane, P. J. Emerging issues in corporate entrepreneurship. Journal of management 2003, 29, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Mustafa, A.; Toglaw, S.; Abidi, O.; Nimer, K. Do individual factors affect the relationship between faculty intrapreneurship and the entrepreneurial orientation of their organizations? Economies 2021, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko. Corporate Entrepreneurship & Innovation, The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship, 2017, ch.14. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen P., H. Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two model of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal 1982, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin J., G.; Slevin D., P. The influence of organizational structure on the utility of an entrepreneurial top management style. Journal of Management Studies 1988, 25, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke J., E.; Liesch P., W. Wait-and-see strategy: Risk management in the internationalization process model. Journal of International Business Studies 2017, 48, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrini, N. J.; Rakhmawati, T.; Sumaedi, S.; Bakti, I. G. M. Y.; Yarmen, M.; Damayanti, S. Innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking: corporate entrepreneurship of Indonesian SMEs. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 722, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, N. S.; Smith, M. (2014). Innovation in entrepreneurial organisations: A platform for contemporary management change and a value creator. The British Accounting Review 2014, 46, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reihlen, M.; Ringberg, T. Uncertainty, pluralism, and the knowledge-based theory of the firm: From J.-C. Spender’s contribution to a socio-cognitive approach. European Management Journal 2013, 31, 76–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Frascati Manual 2015: Guidelines for Collecting and Reporting Data on Research and Experimental Development, The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data, I. I. Oslo manual; Paris and Luxembourg: OECD/Euro-stat, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. F. The discipline of innovation. Harvard business review 2002, 80, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medase, S. K. Product innovation and employees’ slack time. The moderating role of firm age & size. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2020, 5, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsis, T. S.; Simpson, A.; Dehlin, E. Handbook of managerial and organizational innovation; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A. H. The innovation journey: you can’t control it, but you can learn to maneuver it. Innovation 2017, 19, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R. W. Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Academy of management journal 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.; Stalker, G. M. Mechanistic and organic systems. Classics of organizational theory 1961, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, G.; Lumpkin, G. T. Entrepreneurial orientation as a source of innovative strategy. Innovating strategy process 2005, 1, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J. , & Ma, N. (2003). Innovative capability and export performance of Chinese firms. ( 23, 737–747.

- Burgelman, R. A.; Christensen, C. M.; Wheelwright, S. C. Strategic management of technology and innovation; McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, J. C.; Yam, R. C.; Mok, C. K.; Ma, N. A study of the relationship between competitiveness and technological innovation capability based on DEA models. European journal of operational research 2006, 170, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipparini, A.; Sobrero, M. The glue and the pieces: Entrepreneurship and innovation in small-firm networks. Journal of Business Venturing 1994, 9, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y. Y.; Roh, J. W. The analysis for the determinant factors on the outcome of technology innovation among small and medium manufacturers. The Journal of Society for e-Business Studies 2010, 15, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; Burke, G.; Myers, A. Innovation types and performance in growing UK SMEs. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2007, 27, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Villar-López, A. Análisis del papel mediador de las capacidades de innovacion tecnológica en la relación entre la form’a organizativa flexible y el desempeño organizativo. Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa 2010, 13, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, G. D.; White, M. A. The management of technology and innovation: A strategic approach; Thomson South-Western, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K. Z.; Yim, C. K.; Tse, D. K. The effects of strategic orientations on technology-and market-based breakthrough innovations. Journal of Marketing, 2005, 69, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. A. Psychological perspectives on entrepreneurship: Cognitive and social factors in entrepreneurs’ success. Current directions in psychological science, 2000, 9, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrini, N. J.; Rakhmawati, T.; Sumaedi, S.; Bakti, I. G. M. Y.; Yarmen, M.; Damayanti, S. Innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking: corporate entrepreneurship of Indonesian SMEs. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 722, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. A. Psychological perspectives on entrepreneurship: Cognitive and social factors in entrepreneurs’ success. Current directions in psychological science 2000, 9, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorf, R.C.; Byers, T.H. Technology Ventures: from Idea to Enterprise; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burgelman, R. A. Corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management: Insights from a process study. Management science 1983, 29, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Knowledge and entrepreneurial employees: a country-level analysis. Small Business Economics 2013, 41, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Turro, A.; Wright, M.; Zahra, S. Corporate entrepreneurship: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Small Business Economics 2022, 59, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopford, J. M.; Baden-Fuller, C. W. Creating corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic management journal 1994, 15, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A. Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of business venturing 1991, 6, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S. A. Technology strategy and new venture performance: A study of corporate-sponsored and independent biotechnology ventures. Journal of business venturing 1996, 11, 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, D.; Turro, A. , Wright, M.; Zahra, S. Corporate entrepreneurship: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Small Business Economics 2022, 59, 1541-1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J. J. Toward a reconciliation of the definitional issues in the field of corporate entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship theory and practice 1999, 23, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollhammer, H. Internal corporate entrepreneurship. Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship 1982, 209, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Burgelman, R. A. Designs for corporate entrepreneurship in established firms. California management review, 1984, 26, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. J.; Taylor, N. T. Specifying entrepreneurship. Frontiers of entrepreneurship research 1987, 7, 520–532. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, I. C.; Block, Z.; Narasimha, P. S. Corporate venturing: Alternatives, obstacles encountered, and experience effects. Journal of Business Venturing 1986, 1, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchot III, G. Intrapreneuring: Why you don’t have to leave the corporation to become an entrepreneur. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M. H.; Kuratko, D. F.; Covin, J. G. Corporate entrepreneurship & innovation. Cengage Learning, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, V. K.; Yang, Y.; Zahra, S. A. Corporate venturing and value creation: A review and proposed framework. Research Policy 2009, 38, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, J. S.; Kuratko, D. F.; Shepherd, D. A.; Bott, J. P. Managers’ corporate entrepreneurial actions: Examining perception and position. Journal of business venturing 2009, 24, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, P. P.; Oviatt, B. M. Some fundamental issues in international entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 2003, 18, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D. J. The role of managers, entrepreneurs, and the literati in enterprise performance and economic growth. The Role of Managers, Entrepreneurs, and the Literati in Enterprise Performance and Economic Growth 2007, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, J. H.; Yang, H. J. Relationships Among International Entrepreneurship, Core Competence, and Internationalization. Korean Journal of Business Administration 2011, 24, 3247–3271. [Google Scholar]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Ko, A. An empirical investigation of the effect of market orientation and entrepreneurship orientation alignment on product innovation. Organization Science 2001, 12, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. A.; Ahn, Y. S. Analyzing education needs for the development of entrepreneurship of university student. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship 2019, 14, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H. D.; Seo, R. The Effects of Innovative Capabilities and Technological Entrepreneurship of Korean Small and Medium-sized Enterprises on Performance of Technology Management. In ICSB World Conference Proceedings 2011, International Council for Small Business (ICSB).

- Jung, C. H.; Jung, D. H. The effects of strategic orientations on company performance and the moderating role of entrepreneurship in small-medium sized and ventures manufacturing firms. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association 2014, 14, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloodgood, J. M.; Hornsby, J. S.; Burkemper, A. C.; Sarooghi, H. A system dynamics perspective of corporate entrepreneurship. Small business economics 2015, 45, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Menon, A. Making innovation happen in organizations: individual creativity mechanisms, organizational creativity mechanisms or both? Journal of Product Innovation Management 2000, 17, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. H.; Kuratko, D. F.; Covin, J. G. Corporate entrepreneurship & innovation, Cengage Learning. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap-Hinkler, D. , Kotabe, M.; Mudambi, R. A story of breakthrough versus incremental innovation: Corporate entrepreneurship in the global pharmaceutical industry. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2010, 4, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D. F.; Hornsby, J. S.; Hayton, J. Corporate entrepreneurship: the innovative challenge for a new global economic reality. Small Business Economics 2015, 45, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwerth, M.; Schwens, C.; Isidor, R.; Kabst, R. Corporate entrepreneurship and performance: A meta-analysis. Small business economics 2015, 45, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minafam, Z. Corporate entrepreneurship and innovation performance in established Iranian media firms. AD-minister 2019, 34, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Vicente, J. Á.; Alonso-Borrego, C.; Forcadell, F. J.; Galán, J. I. Assessing the effect of public subsidies on firm R&D investment: a survey. Journal of economic surveys 2014, 28, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. , Cui, X., Chen, X., & Zhou, Y. Impact of government subsidies on the innovation performance of the photovoltaic industry: Based on the moderating effect of carbon trading prices. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almus, M.; Czarnitzki, D. The effects of public R&D subsidies on firms’ innovation activities: the case of Eastern Germany. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 2003, 21, 226–236. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Liu, Y. Government support and firm innovation performance: Empirical analysis of 343 innovative enterprises in China. Chinese Management Studies 2015, 9, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. G.; Kim, H. J. The effectiveness of fiscal policies for R&D investment. Journal of Technology Innovation 2009, 17, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J. H.; Lee, B. H. The Role of Government Laboratory within Small Business’ Technology Support Policy; Focusing on Industry-Academy-Laboratory Collaborations. Conference of the Korean Society of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship 2006, 107–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara, M.; Cho, D. S. Cooperative R&D in Japan and Korea: a comparison of industrial policy. Research Policy 2002, 31, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellec, D.; Van Pottelsberghe De La Potterie, B. The impact of public R&D expenditure on business R&D. Economics of innovation and new technology 2003, 12, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinloopen, J. Strategic R&D co-operatives. Research in Economics 2000, 54, 153–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, D.Y.; Yoon, H. D. A Study on the Effect of the Technological Innovation Support System on Venture Company’s Entrepreneurship and Technological Innovation Performance. Journal of the Korean Entrepreneurship Society 2011, 6, 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Binh, B; Park, J. J. A Comparative Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Multiple Policy SME Finance Projects. Asia Pacific Journal of Small Business 2017, 39, 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. S.; Jin, B. H.; Jeong, S. W. The Effects of Internal Capabilities on Export Performance for SMEs that Export their Own Brand: Focused on Moderating Effect of Government Support System. Asia Pacific Journal of Small Business 2015, 37, 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, C.; Lee, C. H. An Analysis on the Moderated Effects of National R&D program on Technological Innovation in the SMEs. Journal of the Korean Production and Operations Management Society 2007, 18, 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E. Y. The Effect of Government Support, Internal R&D and R&D Cooperation on Technological Innovation. Journal of Industrial Economics and Business 2015, 28, 1473–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y. J.; Nam, T. W. Technological Innovation Performance of Small and Mid-sized Business Tax Reduction: Analyzing a Mediation Effect of Entrepreneurship. THE JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE 2019, 26, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. H.; Lee, S. W.; Wi, S. A. The Effect of Government R&D Supports on SME’s Technological Innovation Performance in Korea. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship 2014, 9, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, Y. K. A study on the technological innovation performance & government financial support for venture firms : focused on the multiple mediating effects of external collaboration partners, Korea University. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J. J. Corporate entrepreneurship and small firms growth. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 2010, 10, 386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Maksimov, V.; Gilbert, B. A.; Fernhaber, S. A. Entrepreneurial orientation and international scope: The differential roles of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking. Journal of business venturing 2014, 29, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, G. Innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness in startups: a case study and conceptual development. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 2019, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrini, N. J.; Rakhmawati, T.; Sumaedi, S.; Bakti, I. G. M. Y.; Yarmen, M.; Damayanti, S. Innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking: corporate entrepreneurship of Indonesian SMEs. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 722, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y. H.; Alshallaqi, M. Impact of autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness on students’ intention to start a new venture. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge 2022, 7, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J. J. Corporate entrepreneurship and small firms growth. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 2010, 10, 386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of tax support.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of tax support.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of subsidies.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of subsidies.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of human resource support.

Figure 4.

The moderating effect of human resource support.

Figure 5.

The moderating effect of certification support.

Figure 5.

The moderating effect of certification support.

Figure 6.

The moderating effect of procurement support.

Figure 6.

The moderating effect of procurement support.

Table 1.

Operational definitions of the variables.

Table 1.

Operational definitions of the variables.

| Var. |

Definition |

| CE_iv |

Emphasizing work procedures that pursue change and innovation |

| CE_rt |

A tendency to pursue risk-taking in decision-making |

| CE_pa |

Proactively responding ahead of competitors |

| CE_an |

Emphasizing autonomy and delegation of authority in members |

| CE_ca |

A tendency to pursue competition and expand the market share |

| IP |

New or radically improved products or services compared with existing offerings |

| GS_tax |

Tax deductions or exemptions for research, development of human resources, and industrial technology |

| GS_sub |

Subsidies supporting participation in national research or development projects |

| GS_fin |

Financial support such as investments, loans, guarantees, financial support for technology, assessment of linked technology, and research and development guarantees |

| GS_hr |

Human resources support, including assistance in recruitment, employment recommendations, dispatching, personnel training, appointments, and technological personnel support centers |

| GS_tech |

Technical support, such as technological development, commercialization/transfer of technology, patent strategies, and construction/utilization of infrastructure |

| GS_cert |

Certification support, such as company certification, technology/performance certification, and awards |

| GS_pro |

Procurement support, such as public purchasing, priority procurement recommendations, and superior product designations |

Table 2.

General characteristics.

Table 2.

General characteristics.

| Characteristics (N = 4000) |

Number |

Percentage |

| Number of employees |

10-49 |

1935 |

48.4 |

| 50-99 |

573 |

14.3 |

| 100-299 |

943 |

23.6 |

| 300-499 |

233 |

5.8 |

| >500 |

316 |

7.9 |

| National industrial complex |

Yes |

947 |

23.7 |

| No |

3053 |

76.3 |

| Stock market |

KOSPI |

259 |

6.5 |

| KOSDAQ |

328 |

8.2 |

| KONEX |

14 |

0.4 |

| None |

3399 |

85.0 |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study (N = 4000).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study (N = 4000).

| Variable |

Mean |

Minimum

value |

Maximum

value |

Standard

deviation |

| CE_iv |

3.12 |

1 |

7 |

1.590 |

| CE_rt |

2.90 |

1 |

7 |

1.450 |

| CE_pa |

3.69 |

1 |

7 |

1.470 |

| CE_an |

3.75 |

1 |

7 |

1.406 |

| CE_ca |

4.01 |

1 |

7 |

1.378 |

| GS_tax |

1.21 |

0 |

5 |

1.705 |

| GS_sub |

0.56 |

0 |

5 |

1.296 |

| GS_fin |

0.43 |

0 |

5 |

1.114 |

| GS_hr |

0.38 |

0 |

5 |

1.028 |

| GS_tech |

0.55 |

0 |

5 |

1.290 |

| GS_cert |

0.88 |

0 |

5 |

1.599 |

| GS_pro |

0.30 |

0 |

5 |

0.977 |

| IP |

0.24 |

0 |

1 |

0.426 |

Table 4.

Correlation matrix of the 13 variables used in this study (N = 4000).

Table 4.

Correlation matrix of the 13 variables used in this study (N = 4000).

| Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

| CE_iv |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CE_rt |

0.689** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CE_pa |

0.465** |

0.437** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CE_an |

0.443** |

0.398** |

0.403** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CE_ca |

0.317** |

0.279** |

0.608** |

0.401** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GS_tax |

0.164** |

0.041* |

0.213** |

0.257** |

0.257** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GS_sub |

0.119** |

0.020 |

0.126** |

0.129** |

0.124** |

0.407** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GS_fin |

0.121** |

0.054** |

0.110** |

0.068** |

0.128** |

0.361** |

0.423** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GS_hr |

0.265** |

0.174** |

0.181** |

0.107** |

0.164** |

0.338** |

0.427** |

0.531** |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| GS_tech |

0.437** |

0.384** |

0.348** |

0.255** |

0.300** |

0.372** |

0.332** |

0.405** |

0.535** |

1 |

|

|

|

| GS_cert |

0.371** |

0.259** |

0.325** |

0.266** |

0.272** |

0.496** |

0.361** |

0.341** |

0.413** |

0.643** |

1 |

|

|

| GS_pro |

0.246** |

0.161** |

0.204** |

0.078** |

0.176** |

0.344** |

0.443** |

0.588** |

0.640** |

0.564** |

0.456** |

1 |

|

| IP |

0.160** |

0.128** |

0.115** |

0.037* |

0.176** |

0.166** |

0.120** |

0.254** |

0.237** |

0.231** |

0.134** |

0.238** |

1 |

Table 5.

Two-stage logistic regression of the effects of five factors of CE on IP (N = 4000).

Table 5.

Two-stage logistic regression of the effects of five factors of CE on IP (N = 4000).

| Variable |

B |

S.E |

Wald |

Df |

Sig. |

OR |

95% CI |

| Lower |

Upper |

| CE_iv |

0.234 |

0.023 |

100.430 |

1 |

0.000 |

1.263 |

1.207 |

1.322 |

| CE_rt |

0.203 |

0.025 |

64.001 |

1 |

0.000 |

1.225 |

1.166 |

1.288 |

| CE_pa |

0.190 |

0.026 |

52.573 |

1 |

0.000 |

1.209 |

1.148 |

1.272 |

| CE_an |

0.062 |

0.027 |

5.447 |

1 |

0.020 |

1.064 |

1.010 |

1.121 |

| CE_ca |

0.317 |

0.029 |

119.363 |

1 |

0.000 |

1.373 |

1.297 |

1.453 |

Table 6.

The moderating effect of tax support.

Table 6.

The moderating effect of tax support.

| |

Coeff. |

S.E. |

Z |

LLCI |

ULCI |

| (constant) |

-2.191 |

0.167 |

-13.094*** |

-2.518 |

-1.863 |

| CE |

0.217 |

0.046 |

4.708*** |

0.126 |

0.307 |

| GS_tax |

-0.056 |

0.080 |

-0.698 |

-0.212 |

0.101 |

| int |

0.060 |

0.020 |

2.998*** |

0.021 |

0.099 |

| |

ModelLL=184.507 (df=3, p=0.000), Cox-Snell=0.042, Nagelkrk=0.068 |

Table 7.

The moderating effects of tax support on CE and IP.

Table 7.

The moderating effects of tax support on CE and IP.

| Independent variable |

Interaction term |

| Coeff. |

S.E. |

Z |

LLCI |

ULCI |

| CE_iv |

0.048 |

0.013 |

3.654*** |

0.022 |

0.073 |

| CE_rt |

0.046 |

0.014 |

3.222*** |

0.018 |

0.073 |

| CE_pa |

-0.003 |

0.015 |

-0.176 |

-0.032 |

0.027 |

| CE_an |

0.019 |

0.016 |

1.170 |

-0.013 |

0.051 |

| CE_ca |

0.023 |

0.017 |

1.384 |

-0.010 |

0.056 |

Table 8.

The moderating effect of subsidies.

Table 8.

The moderating effect of subsidies.

| |

Coeff. |

S.E. |

Z |

LLCI |

ULCI |

| (constant) |

-2.342 |

0.147 |

-15.922*** |

-2.631 |

-2.054 |

| CE |

0.299 |

0.039 |

7.725*** |

0.223 |

0.375 |

| GS_sub |

-0.152 |

0.115 |

-1.317 |

-0.378 |

0.074 |

| int |

0.079 |

0.028 |

2.795*** |

0.023 |

0.134 |

| |

ModelLL=154.627 (df=3, p=0.000), Cox-Snell=0.038, Nagelkrk=0.057 |

Table 9.

The moderating effects of subsidies on CE and IP.

Table 9.

The moderating effects of subsidies on CE and IP.

| Independent variable |

Interaction term |

| Coeff. |

S.E. |

Z |

LLCI |

ULCI |

| CE_iv |

0.010 |

0.017 |

0.584 |

-0.023 |

0.042 |

| CE_rt |

0.032 |

0.019 |

1.669* |

-0.006 |

0.070 |

| CE_pa |

0.050 |

0.019 |

2.583** |

0.012 |

0.087 |

| CE_an |

0.008 |

0.024 |

0.326 |

-0.038 |

0.055 |

| CE_ca |

0.076 |

0.023 |

3.258*** |

0.030 |

0.121 |

Table 10.

The moderating effect of financial support.

Table 10.

The moderating effect of financial support.

| |

Coeff. |

S.E. |

Z |

LLCI |

ULCI |

| (constant) |

-2.619 |

0.152 |

-17.261*** |

-2.917 |

-2.322 |

| CE |

0.341 |

0.040 |

8.623*** |

0.263 |

0.418 |

| GS_fin |

0.563 |

0.117 |

4.826*** |

0.334 |

0.792 |

| int |

-0.038 |

0.029 |

-1.290 |