Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Cashless in Southeast Asia and Malaysia

2.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT 2) Model and the Technology Readiness Index (TRI 2.0) Model

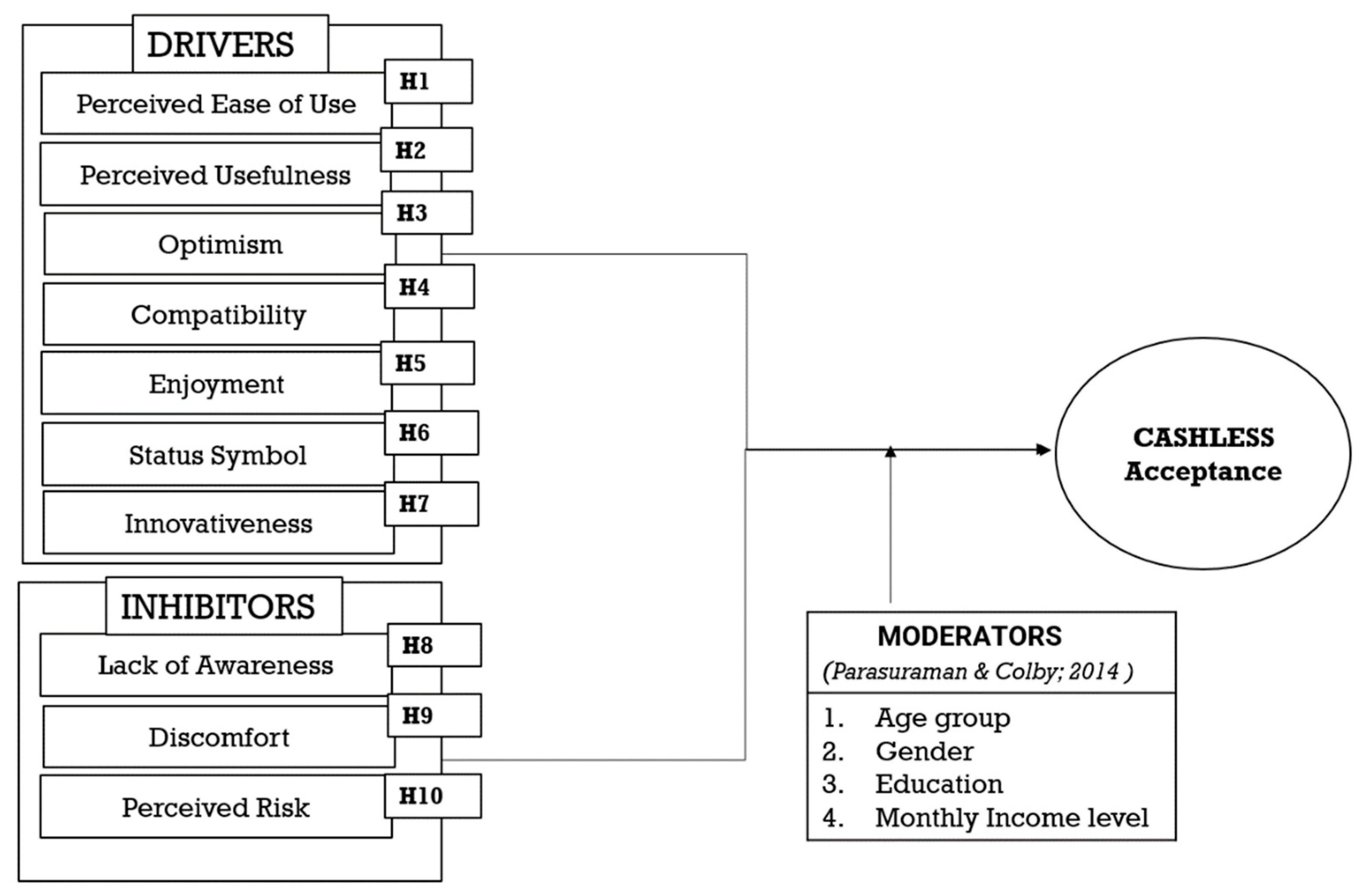

2.3. Theoretical Implications and Hypotheses Affecting the Acceptance to Use Cashless Payment Services

2.3.1. Perceived Ease of Use

2.3.2. Perceived Usefulness

2.3.3. Optimism

2.3.4. Compatibility

2.3.5. Enjoyment

2.3.6. Status Symbol

2.3.7. Innovativeness

2.3.8. Lack of Awareness

2.3.9. Discomfort

2.3.10. Perceived Risk

3. Methodology

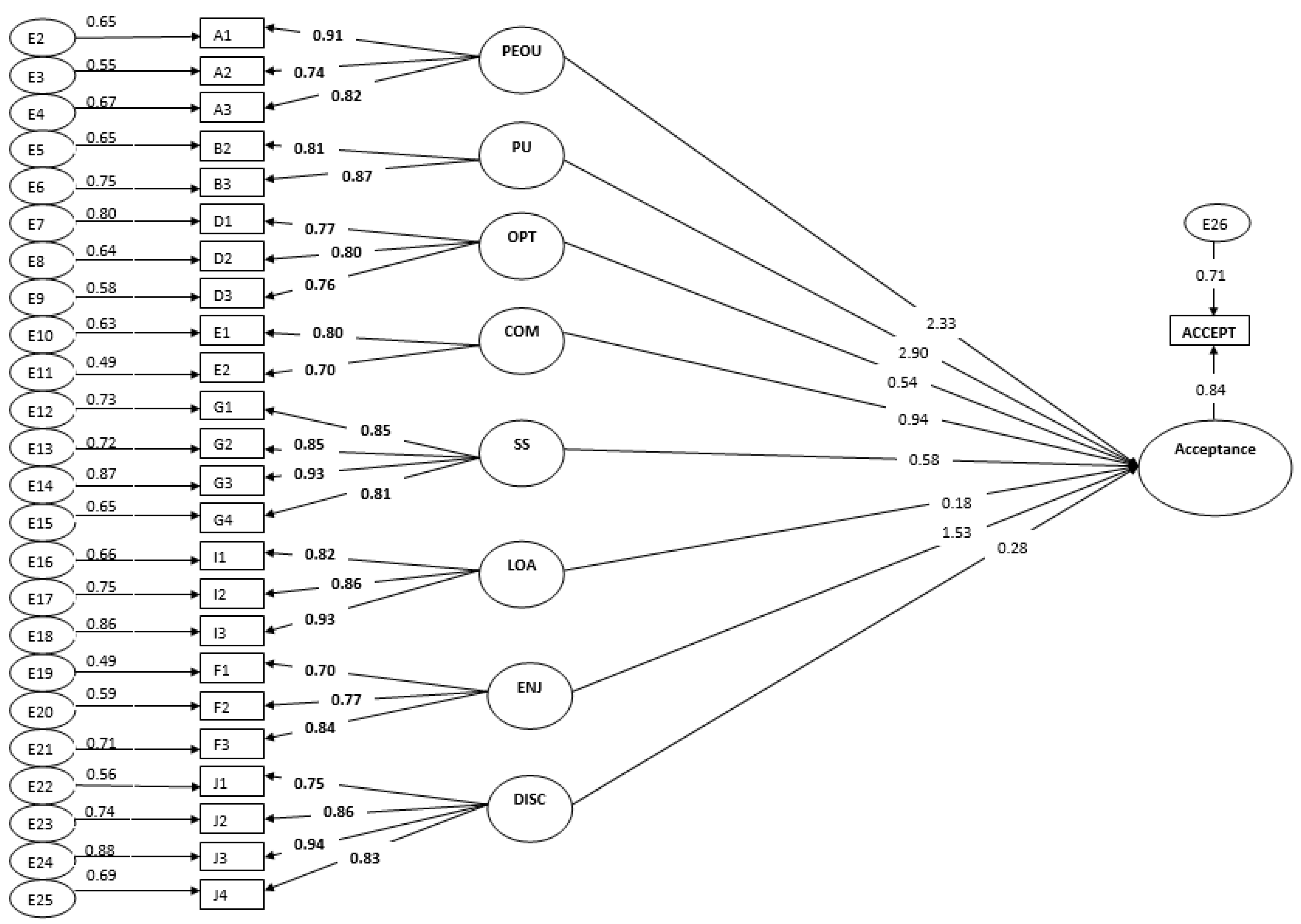

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Respondents

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Reliability Evaluation

4.1. Goodness-of-Fit of the Framework

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusion, Implication, Limitation and Future Work

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations

References

- Kadar HH, B.; Sameon SS, B.; Din MB, M.; Rafee PA, B.A. Malaysia towards cashless society. International Symposium of Information and Internet Technology; Springer: Cham, 2018; pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Din MB, M.; Rafee PA, B.A. Malaysia towards cashless society. Proceedings of the 3rd international symposium of information and internet technology (SYMINTECH 2018. 565; Springer, 2019; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Humbani, M.; Wiese, M. A cashless society for all: Determining consumers’ readiness to adopt mobile payment services. Journal of African Business 2018, 19, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Colby, C.L. An updated and streamlined technology readiness index:TR 2.0. Journal of Service Research 2014, 18, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. Technology readiness index (TRI): A multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of Service Research 2000, 2, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fripp, C. http://www.htxt.co.za/ 2014/10/23/south-africas-mobile-penetration-is-133/. 2014. Available online: http://www.htxt.co.za/ 2014/10/23/south-africas-mobile-penetration-is-133/.

- GSMA. (2016). State of the industry report on mobile money.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. [CrossRef]

- De Kerviler, G.; Demoulin NT, M.; Zidda, P. Adoption of in-store mobile payment: Are perceived risk and convenience the only drivers? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 31, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, N.A.; Antony, G.V. A critical review of information-security threats faced by Indian banks. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science and Management Studies 2016, 4, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat MI, R.M.; Al Rababaa, M.S. Assessing key factors that have an influence on the acceptance of mobile commerce, based on modified UTAUT. International Journal of Business and Management 2013, 8, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Hall, D.; Sun, S. (2014). The effect of technology usage habits on consumers’ intention to continue to use mobile payments. Twentieth Americans Conference on Information Systems (pp. 1–12). Savannah; pp. 1–12.

- Karjaluoto, H.; Leppaniemi, M.; Standing, C.; Kajalo, S.; Merisavo, M.; Virtanen, V.; Salmenkivi, S. Individual differences in the use of mobile services among Finnish consumers. International Journal of Mobile Marketing 2006, 1, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kımıloğlu, H.; Aslıhan Nasır, V.A.; Nasır, S. Discovering behavioral segments in the mobile phone market. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2010, 27, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwanuka, A. Acceptance process: The missing link between UTAUT and diffusion of innovation theory. American Journal of Information Systems 2015, 3, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Park, J.-H.; Chung, N.; Blakeney, A. A unified perspective on the factors influencing usage intention toward mobile financial services. Journal of Business Research 2012, 65, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Shi, X.; Wong, W.-K. Consumer perceptions of the smartcard in retailing: An empirical study. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 2012, 24, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; De Luna, I.R.; Montoro-Ríos, F.J. User behaviour in QR mobile-payment system: The QR payment acceptance model. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2015, 27, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-H.; Shih, H.-Y.; Sher, P.J. Integrating technology readiness into technology accep-tance: The TRAM model. Psychology & Marketing 2007, 24, 641–657. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F.H.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson-Prentice Hall.

- Herzberg, A. Payments and banking with mobile personal devices. Communications of the ACM 2003, 46, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural-equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mallat, N. Exploring consumer adoption of mobile payments – A qualitative study. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2007, 16, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changsu Kim, Mir obit Mirusmonov, In Lee, An empirical examination of factors influencing the intention to use mobile payment, Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 26, Issue 3,2010,Pages 310-322,ISSN 0747-5632. [CrossRef]

- Bilińska-Reformat, K.; Kieżel, M. (2016). Retail banks and retail chains cooperation for the promotion of the cashless payments in Poland. Twentieth Americans Conference on Information Systems (pp. 1–12). Savannah, Venice, Poland.

- Krüger, M.; Seitz, F. (2014). Costs and benefits of cash and cashless payment instruments: Overview and initial estimates. Study commissioned by the Deutsche Bundesbank. Frankfurt,Germany.

- World Payment Report (2020). Non-cash payments volume. Available online: https://worldpa ymentsreport.com/non-cash-payments-volume-2/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Golobal Trade (2020). Toward a global cashless economy. Available online: https://www. globaltrademag.com/toward-a-global-cashless-economy/.

- Research and Market (2020). Global cards & payments market insights, 2015–2019 & 2019–2023. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/04/ 16/2017151/0/en/Global-Cards-Payments-Market-Insights-2015-2019-2019-2023. Html.

- Pikri, E. (2019). How cashless is Malaysia right now? 1996. Available online: https:// fintechnews.my/19964/payments-remittance-malaysia/cashless-malaysia-credit-debitca rd-e-wallet-money/ (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Bank Negara Malaysia (2019). Malaysia's payment statistics. Available online: http://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=ps&pg=ps_stats&lang=en.

- Mering, R. (2019). Survey: More Malaysians prefer cashless payment with debit cards, online banking. Retrieved 11 July 2019. Available online: https://www.malaymail.com/news/money/ 2019/01/17/survey-more-malaysians-prefer-cashless-payment-with-debit-cards-onlinebank/1713682.

- Teo, A.C.; Tan, G.W.; Ooi, K.B.; Hew, T.S.; Yew, K.T. The effects of convenience and speed in m-payment. Industrial Management and Data Systems 2015, 115, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Jain, A.; Angus, M. (2013). Measuring progress toward a cashless society. MasterCard advisors (pp. 1–5) Retrived 11 July 2019. 11 July. Available online: https://newsroom.mastercard. com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/MasterCardAdvisors-CashlessSociety-July-20146.pdf.

- Nagdev, K.; Rajesh, A.; Misra, R. (2021). The mediating impact of demonetisation on customer acceptance for IT-enabled banking services. International Journal of Emerging Markets. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Al Mamun, A.; Mohiuddin, M.; Nawi, N.C.; Zainol, N.R. (2021). Cashless transactions: A study on intention and adoption of e-wallets. Sustainability (Switzerland). [CrossRef]

| Factors | Model/References | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Drivers | ||

| Perceived Usefulness | UTAUT2 | It is a degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his/her job performance |

| Perceived Ease of Use | UTAUT2 | The extent to which using a digital payment service is easy. |

| Innovativeness | TRI 2.0 | Inclination of an individual to try out any new information systems |

| Optimism | TRI 2.0 | Positive view of digital payment technology and a belief that it offers people increased control, flexibility, and efficiency in their lives |

| Compatibility | Wiese, M. (2017). | Consistency between digital payment technology and its values, experiences and the needs of potential adopters. |

| Status Symbol | Rena, Z., Salehuddin, M., Zahari, M., & Rosmini, I. (2013)). | The extent to which using digital payment services is deemed as a status symbol |

| Enjoyment | UTAUT 2 | The extent to which using the digital payment services is considered fun |

| Inhibitors | ||

| Lack of Awareness | Oliveria, T. Thomas M., Baptista, G., & Campos, F. (2017). | The failure to be alert of new digital payment technologies. |

| Perceived Risk | TRI 2.0 | The extent to which using the digital payment service incurs costs to the customer |

| Discomfort | TRI 2.0 | Perceived lack of control over digital payment technology and a feeling of being overwhelmed by it |

| Dependent variable | ||

| Cashless Acceptance | The level of acceptance to use cashless payment services | Redefined from TRI 2.0, UTAUT2 and External Factors |

| Sample Characteristic | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 246 | 56.7 |

| Male | 188 | 43.3 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 25 | 76 | 17.5 |

| 25 - 50 | 335 | 77.2 |

| More than 51 | 23 | 5.3 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 4 | 0.9 |

| Tertiary | 276 | 63.6 |

| Post-Graduate | 154 | 35.5 |

| Income | ||

| < 3,000 (MYR (< 714 USD) | 110 | 25.3 |

| 3,000 - 10,000 (MYR)(714 – 2380 USD) | 270 | 62.2 |

| > 10,000 (MYR)(> 2380 USD) | 54 | 12.4 |

| Use of Digital Payment | ||

| No | 33 | 7.6 |

| Yes | 401 | 92.4 |

| Frequency (weekly) | ||

| 4 – 9 times | 186 | 42.9 |

| < 3 times | 178 | 41.0 |

| >10 times | 70 | 16.1 |

| Services (apps) | ||

| GrabPay | 211 | 48.6 |

| JomPay | 135 | 31.1 |

| Maybank QR Pay | 144 | 33.1 |

| Boost | 112 | 25.8 |

| More than one | 157 | 36.1 |

| Factors | Items | Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Ease of Use (A1-A3) | I find it easy to use digital payments | A1: 0.91 |

| I find it easy to learn to use digital payments | A2: 0.74 | |

| I find it easy to install digital payment application | A3: 0.82 | |

| Perceived Usefulness (B1 – B3) | Using digital payment would help me to manage my expenses better | B1: 0.61 |

| It is convenient to pay digitally | B2: 0.81 | |

| Digital payment enables me to make payment efficiently | B3: 0.87 | |

| Innovativeness (C1-C3) | I am interested in keeping up with the latest digital payment application. | C1: 1.01 |

| I am interested in using latest digital payment application | C2: 0.67 | |

| I don’t mind trying digital payment application that is new to the market | C3: 0.37 | |

| Optimism (D1-D3) | I belief payments can be successfully completed using digital payments | D1: 0.77 |

| I feel that digital payment is the lead towards the future. | D2: 0.80 | |

| I belief that digital payment provides flexibility | D3: 0.76 | |

| Compatibility (E1-E2) | My lifestyle fits digital payment | E1: 0.80 |

| I have the means to use digital payment (e.g. smartphones) | E2: 0.70 | |

| Enjoyment (F1-F3) | I find it fun using digital payment | F1: 0.70 |

| I enjoy using digital payment in my daily life | F2 0.87 | |

| It gives me satisfaction in making payments using digital payments | F3: 0.84 | |

| Status Symbol(G1-G4) | Digital payments enhance my status | G1: 0.85 |

| Digital payment makes me look professional | G2: 0.85 | |

| Digital payment enhances my confidence | G3: 0.93 | |

| I find it cool in using digital payment | G4: 0.81 | |

| Perceived Risk (H1-H4) | I don’t feel secure in using digital payment | H1: 0.60 |

| I am concerned about my online privacy | H2: 0.24 | |

| I feel uncomfortable as there are too many security breaches lately. | H3: 0.62 | |

| I just don’t trust any online payment mechanism | H4: 0.63 | |

| Lack of Awareness(I1-I3) | I don’t know where I can use digital payments (e.g. restaurant) | I1: 0.82 |

| I am not aware of digital payments available | I2: 0.86 | |

| I don’t know when I can use digital payment | I3: 0.93 | |

| Discomfort (J1-J4) | I find it tedious in always maintaining my credit balance. | J1: 0.75 |

| I find it tedious in setting up digital payment | J2: 0.86 | |

| I find it uncomfortable in carrying my technology device around (e.g. laptop, smart phones) | J3: 0.94 | |

| There are too many hassles in carrying around digital payment (e.g. forgetting to carry around mobile phones, battery dead) | J4: 0.83 |

| Construct | Items Description | Items and Factor Loading | Cronbach’s alpha (CA) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (CR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Ease of Use | I find it easy to use digital payments | A1: 0.91 | 0.826 | 0.69 | 0.82 |

| I find it easy to learn to use digital payments | A2: 0.74 | ||||

| I find it easy to install digital payment application | A3: 0.82 | ||||

| Perceived Usefulness | It is convenient to pay digitally | B2: 0.81 | 0.815 | 0.70 | 0.77 |

| Digital payment enables me to make payment efficiently | B3: 0.87 | ||||

| Optimism | I belief payments can be successfully completed using digital payments | D1: 0.77 | 0.861 | 0.60 | 0.73 |

| I feel that digital payment is the lead towards the future. | D2: 0.80 | ||||

| I belief that digital payment provides flexibility | D3: 0.76 | ||||

| Compatibility | My lifestyle fits digital payment | E1: 0.80 | 0.717 | 0.60 | 0.72 |

| I have the means to use digital payment (e.g. smartphones) | E2: 0.70 | ||||

| Enjoyment | I find it fun using digital payment | F1: 0.70 | 0.863 | 0.60 | 0.73 |

| I enjoy using digital payment in my daily life | F2 0.87 | ||||

| It gives me satisfaction in making payments using digital payments | F3: 0.84 | ||||

| Status Symbol | Digital payments enhance my status | G1: 0.85 | 0.911 | 0.74 | 0.89 |

| Digital payment makes me look professional | G2: 0.85 | ||||

| Digital payment enhances my confidence | G3: 0.93 | ||||

| I find it cool in using digital payment | G4: 0.81 | ||||

| Lack of Awareness | I don’t know where I can use digital payments (e.g. restaurant) | I1: 0.82 | 0.903 | 0.76 | 0.88 |

| I am not aware of digital payments available | I2: 0.86 | ||||

| I don’t know when I can use digital payment | I3: 0.93 | ||||

| Discomfort | I find it tedious in always maintaining my credit balance. | J1: 0.75 | 0.892 | 0.72 | 0.88 |

| I find it tedious in setting up digital payment | J2: 0.86 | ||||

| I find it uncomfortable in carrying my technology device around (e.g. laptop, smart phones) | J3: 0.94 | ||||

| There are too many hassles in carrying around digital payment (e.g. forgetting to carry around mobile phones, battery dead) | J4: 0.83 |

| Construct | p-value | Hypothesis and Remark |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Ease of Use | 0.005 | H1 Supported |

| Perceived Usefulness | 0.004 | H2 Supported |

| Optimism | 0.465 | H3 Not Supported |

| Compatibility | 0.505 | H4 Not Supported |

| Enjoyment | 0.254 | H5 Not Supported |

| Status Symbol | 0.118 | H6 Not Supported |

| Lack of Awareness | 0.127 | H8 Not Supported |

| Discomfort | 0.012 | H9 Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).