1. Introduction

Recent trials suggest that pre-stroke use of antiplatelets with or without statins is associated with reduced severity and better functional outcome of ischemic strokes, particularly in those with no prior history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) [

1,

2]. Moreover, the pre-stroke use of statins is independently associated with reduced stroke severity at presentation and better early functional recovery in patients with acute ischemic stroke [

3]. Traditionally, most studies used The National Institutes of Health Stroke

Scale (NIHSS score)1 to measure stroke severity, while the modified Rankin Score (mRS score)2 was used as a primary measure of functional outcome. A growing number of studies suggest that the long-term use of

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/ angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) pre-stroke may be beneficial in reducing stroke severity at onset (measured by NIHSS score on admission) and better functional outcome (as measured by mRS score at discharge) [

4]. However, these findings must be validated in larger-scale randomized studies, particularly the independent effect of pre-stroke use of ACEI/ARB.

Table 1.

Research summary for the effect of pre-stroke treatment with ACEI/ARB, antiplatelets, and/or statins on stroke severity and functional outcome.

Table 1.

Research summary for the effect of pre-stroke treatment with ACEI/ARB, antiplatelets, and/or statins on stroke severity and functional outcome.

| Paper |

Main finding |

| Pre-stroke use of antihypertensive, antiplatelets, or statins and early ischemic stroke outcomes [5]. |

Pre-stroke use of statins and the combination of antihypertensive, antiplatelets, and statins were associated with a favorable functional outcome at ten days post-stroke. Conversely, angiotensin-II-decreasing agents were associated with increased initial stroke severity. |

| Antiplatelets, ACE inhibitors, and statin combination reduces stroke severity and tissues at risk [6]. |

Using a combination of available drugs for stroke prevention may reduce stroke severity, as measured by NIH Stroke Scale, and the volume of ischemic tissue at risk, as assessed by perfusion-weighted imaging–diffusion-weighted imaging mismatch. These findings require further validation in larger-scale, randomized, prospective studies. |

------------------------------------------------------------------

1 The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a tool healthcare providers use to objectively quantify the impairment caused by a stroke. The NIHSS comprises 11 items, each scoring a specific ability between 0 and 4. For each item, a score of 0 typically indicates a normal function in that specific ability, while a higher score indicates some level of impairment. Each item’s scores are summed to calculate a patient's total NIHSS score. The maximum and minimum possible score is 42 and 0, respectively.

2 The

modified Rankin Scale (

mRS) is a commonly used scale for measuring the degree of disability or dependence in the daily activities of people who have suffered a stroke or other causes of neurological disability.

The scale runs from 0-5, from perfect health without symptoms to severe disability.

| Effect of pretreatment with statins on the severity of acute ischemic cerebrovascular events [7]. |

Pretreatment with statins seems to be associated with reduced clinical severity in patients with acute ischemic cerebrovascular events, particularly in patients with diabetes. |

| Effect of pre-stroke statin use stroke severity and early functional recovery: a retrospective cohort study [3]. |

Pre-stroke statin use was associated with reduced stroke severity at presentation and improved early functional recovery in patients with acute ischemic stroke. |

| Is pre-stroke use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors associated with better outcomes? [8]. |

Within this large community-based cohort, pre-stroke use of ACEI was associated with a reduced risk of severe stroke. |

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

We retrospectively studied 218 patients who presented with ischemic stroke and were admitted to the stroke unit in Tzafon medical center between 2019-2020. The stroke was confirmed by a clinical presentation (serial neurological examinations performed by stroke-trained neurologists) and brain CT/CTA images. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed In many patients to confirm their clinical diagnosis. When the patient presented at the clinic, we calculated and used the NIHSS score as the primary measure of clinical stroke severity. We adopted changes in the modified ranking scale (mRS ) from the pre-stroke mRS state to measure functional outcomes. We included patients who had received thrombolytic treatment. We excluded patients with questionable diagnoses, those referred to other medical centers for endovascular treatment, and those with a negative diffusion weighted image/perfusion weighted image (DWI/PWI).

2.2. Data Collection and Assessment

We obtained the following data from all patients: demographic data; risk factors for stroke, i.e., hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation (AF), and smoking, as reported by the patient and their family; and medications upon admission, particularly antiplatelets, anticoagulants, statins, and antihypertensives including ACEI/ARB. We contested the duration of medication(s) use, daily use and compliance. Patients with poor compliance with medication use were excluded (particularly in the last week before the stroke occurred).

The baseline Modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

NIHSS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) at admission.

mRS and NIHSS scores at discharge.

The last three data were assessed and calculated by stroke-trained neurologists qualified to apply both measures.

2.3. Outcome Measures

We assessed patients at presentation using the NIHSS score as the primary measure of clinical stroke severity. On discharge, we adopted the change of mRS scale from the baseline mRS scale to measure the functional outcome of a stroke. A stroke was radiologically confirmed in all patients by CT/CTA brain images. In many patients, a brain MRI was performed to confirm a diagnosis. The brain MRIs were assessed and reported by specialist radiologists certified in MRI radiology.

2.4. Statistical Workup

For both of these variants (NIHSS score on admission and MRS change on discharge), we separately compared two major groups and four subgroups:

The overall number of patients taking ACEI/ARB compared to those who were not.

Of particular clinical significance, we compared patients taking ACEI/ARB to those not, among all patients not taking statins or antiplatelets. This direct comparison evaluated if the pre-stroke use of ACEI/ARB had an independent effect on stroke severity and functional outcome by removing any possible advantage of statins and/or antiplatelets.

Patients taking ACEI/ARB and on statin treatment versus those on statin treatment not taking ACEI/ARB.

Patients taking ACEI/ARB and antiplatelet treatment versus those on antiplatelet treatment not taking ACEI/ARB.

Patients on ACEI/ARB and antiplatelet and statin treatment versus those on antiplatelet and statin treatment not taking ACEI/ARB.

The intersectional comparison between the last three subgroups allowed us to evaluate whether the pre-stroke use of ACEI/ARB has additional benefits over using antiplatelets and/or statins on both severity and stroke outcome.

2.5. Inclusion Criteria

Patients of all ages presenting with ischemic stroke confirmed by a serial neurological examination (performed by a stroke-specialist neurologist) and radiological evidence from brain CT, CTA, or MRI.

2.6. Exclusion Criteria

Patients with an uncertain diagnosis or with a high potential for an alternate diagnosis were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria include in compliance with medication, particularly to the use of ACEI/ARB, antiplatelets, and statins; pre-morbid debilitated and frail states where changes in mRS state and the functional outcome may be largely influenced by other co-morbidities besides a stroke; and referral to other medical centers for endovascular intervention.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Patients were divided into two major groups: those taking ACEI/ARB before their stroke and those who had not. We compared inter-group differences between individual categorical variables. SPSS version 23 was utilized to run the following list of tests and define results. We used statistical tools to examine the hypothesis and questions as follows:

Frequencies and percentages to describe the characteristics of the patient characteristic.

The median and the first and third quartiles of the interquartile range for non-normally distributed data.

For non-normally distributed data, a Mann-Whitney U Test was used to examine the differences in the functional outcome (change in mRS score) and stroke severity (NIHSS score on admission).

A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics (Demographic and Clinical Profiles)

Two hundred and eighteen patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in subsequent analyses. Among these, 119 patients (54%) were taking ACEI (34%) or ARB (20%) before the stroke occurred.

Table 2 summarizes the patient’s demographic and clinical features in the ACEI/ARB treated and non-treated groups.There were no significant differences in the mean age or sex distribution between the two groups. Expectedly, a significantly higher percentage of ACEI/ARB-treated patients had a history of HTN and hyperlipidemia and were taking antiplatelets and/or statins compared to the non-ACEI/ARB group. Slightly higher but statically insignificant percentages of ACEI/ARB-treated patients had diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation. There was no significant difference in the distribution of smokers between the two groups.

3.2. Outcomes

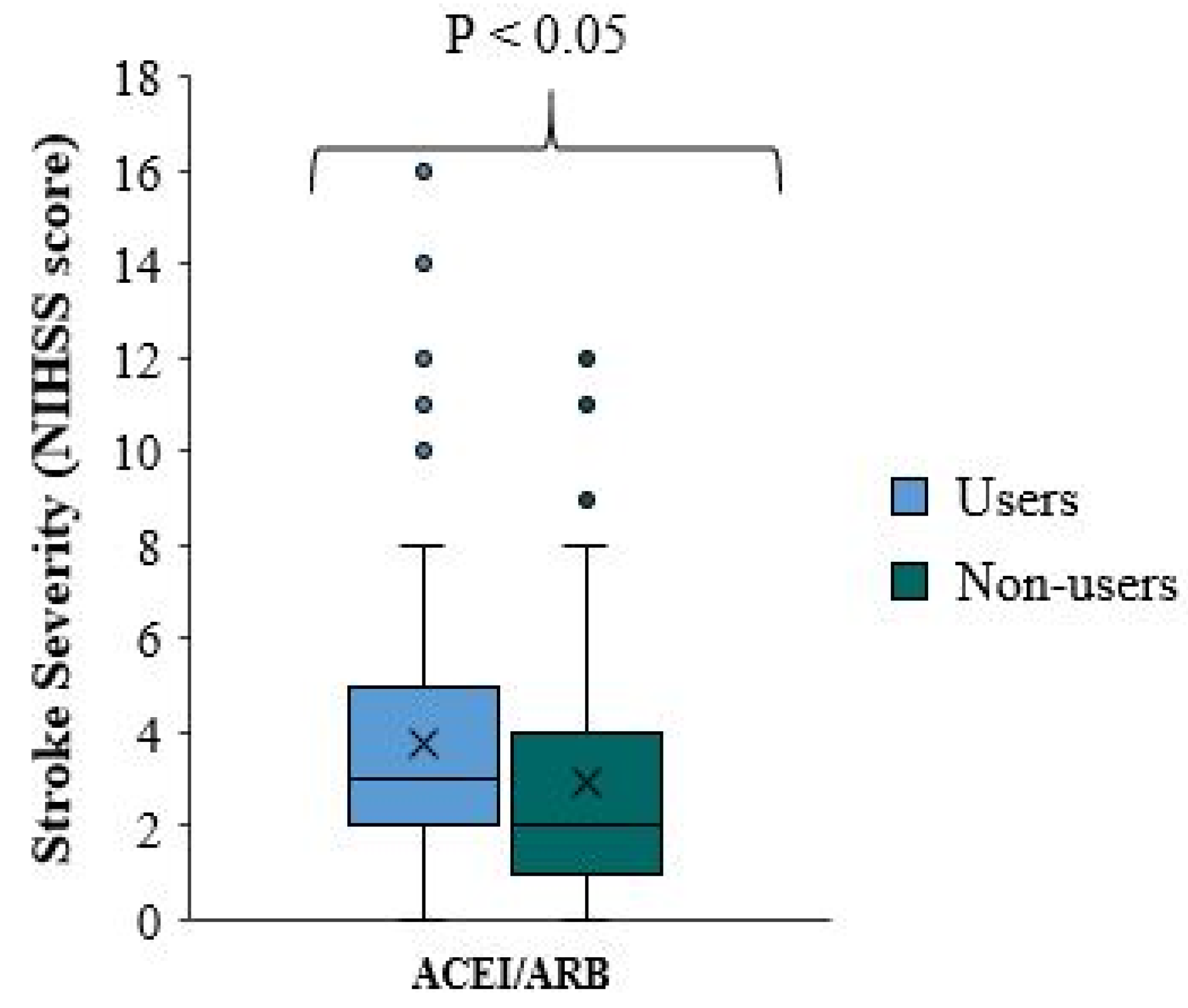

3.2.1. Difference in Stroke Severity (NIHSS Score at Admission) between ACEI/ARB Treated Patients and ACEI/ARB Non-Treated Patients

There is a significant difference in stroke severity between ACEI/ARB users and non-users (p-value=0.010), with reduced NIHSS scores and milder stroke severity among ACEI/ARB non-treated patients who received ACEI/ARB prior to the onset of the stroke (

Table 3,

Figure 1). The median NIHSS score for ACEI/ARB users is one point higher than that for ACEI/ARB non-users. In approximately 75% of patients, the NIHSS score is less than five in ACEI/ARB and less than four in ACEI/ARB non-users (

Figure 1).

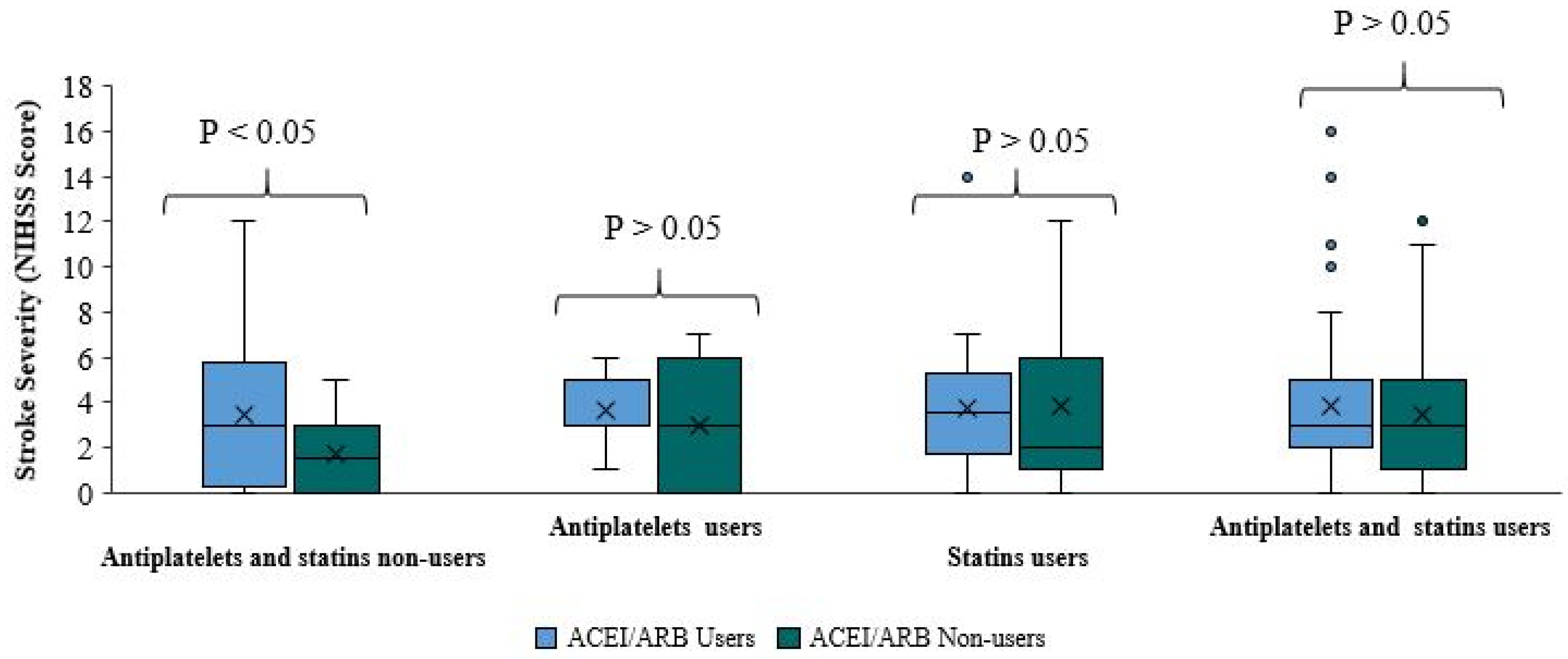

This unexpected result was further confirmed when the same variant was compared between patients taking ACEI/ARB and those not, among all patients not taking statins and/or antiplatelets. There was a milder stroke severity and reduced median NIHSS score in patients not taking ACEI/ARB. This difference was not statistically significant (p-value=0.071). The median NIHSS score of ACEI/ARB users is higher by 1.5 points than in ACEI/ARB non-users. In approximately 75% of the patients, the NIHSS score is less than 5.75 in the first group and less than 3 in the second group (

Figure 2). To our knowledge, this study is among a few studies with relatively large sample sizes, allowing direct statistically-significant comparisons between ACEI/ARB users and non-users who are not taking statins or antiplatelets. This comparison is of clinical significance to assess the independent effect of ACEI/ARB on stroke severity by removing any possible additive/primary effect of concomitant treatment with antiplatelets and/or statins. This direct comparison of an independent effect of ACEI/ARB showed that pre-stroke treatment with ACEI/ARB was associated with worse stroke severity on admission, validated by significant statistical indexes.

There was no significant difference in stroke severity between ACE/ARB users and non-users in patients taking antiplatelets, statins, or both (Table 3,

Figure 2). Among patients taking antiplatelets without statins, there was no significant difference in the NIHSS score between ACEI/ARB users and ACEI/ARB non-users (p-value=0.631). The median score of the two groups was roughly equal. In approximately 75% of ACEI/ARB and antiplatelet users, the score was less than 5, compared to less than 6 in 75% of patients taking antiplatelets without ACEI/ARB. There was no significant difference in NIHSS score between ACEI/ARB users and ACEI/ARB non-users (p-value=0.674) among patients taking statins without antiplatelets. The median NIHSS score of ACEI/ARB and statins users is higher than the median score of patients using statins without ACE/ARB. In approximately 75% of patients taking statins and ACEI/ARB the score was 5.25; in 75% of patients taking statins without ACEI/ARB the score was less than 6. Moreover, there was no significant difference in NIHSS scores among patients taking antiplatelets and statins between ACEI/ARB users and ACEI/ARB non-users (p-value=0.404). The median NIHSS score of both sub-groups was roughly equal. In approximately 75% of patients in both sub-groups, the NIHSS score was less than 5.

When the NIHSS score was compared between ACEI/ARB users and non-users in these three subgroups, it is clear that the addition of ACEI/ARB to pre-stroke treatment with antiplatelets, statins, or both did not reduce stroke severity. Nevertheless, patients taking ACEI/ARB appeared to have milder stroke severity; however, this finding was not statistically significant.

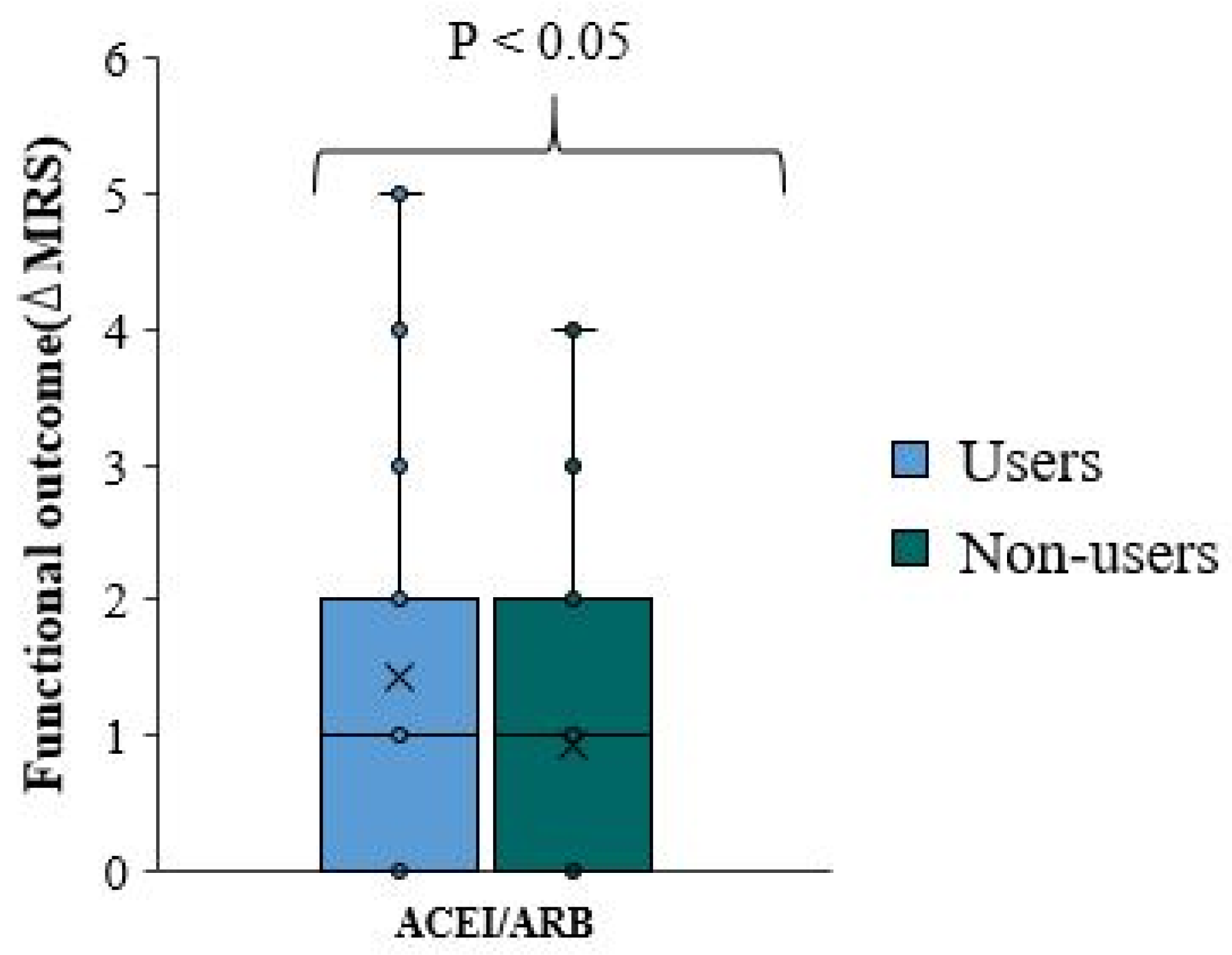

3.2.2. Difference in Functional Outcome (Changes in MRS Score) between ACEI/ARB Treated Patients and ACEI/ARB Non-Treated Patients

We used the change in mRS scale at discharge from the baseline pre-stroke mRS scale as a negative measure of functional outcome. Thereafter, we refer to the change in mRS score as ΔmRS. There is no significant difference in functional outcome and ΔmRS between overall ACEI/ARB users and non-user (p-value=0.006)(

Table 4,

Figure 3). The ΔmRS median for ACEI/ARB users and ACEI/ARB non-users was equal. In approximately 75% of patients, the ΔmRS is less than two in both groups (

Figure 3).

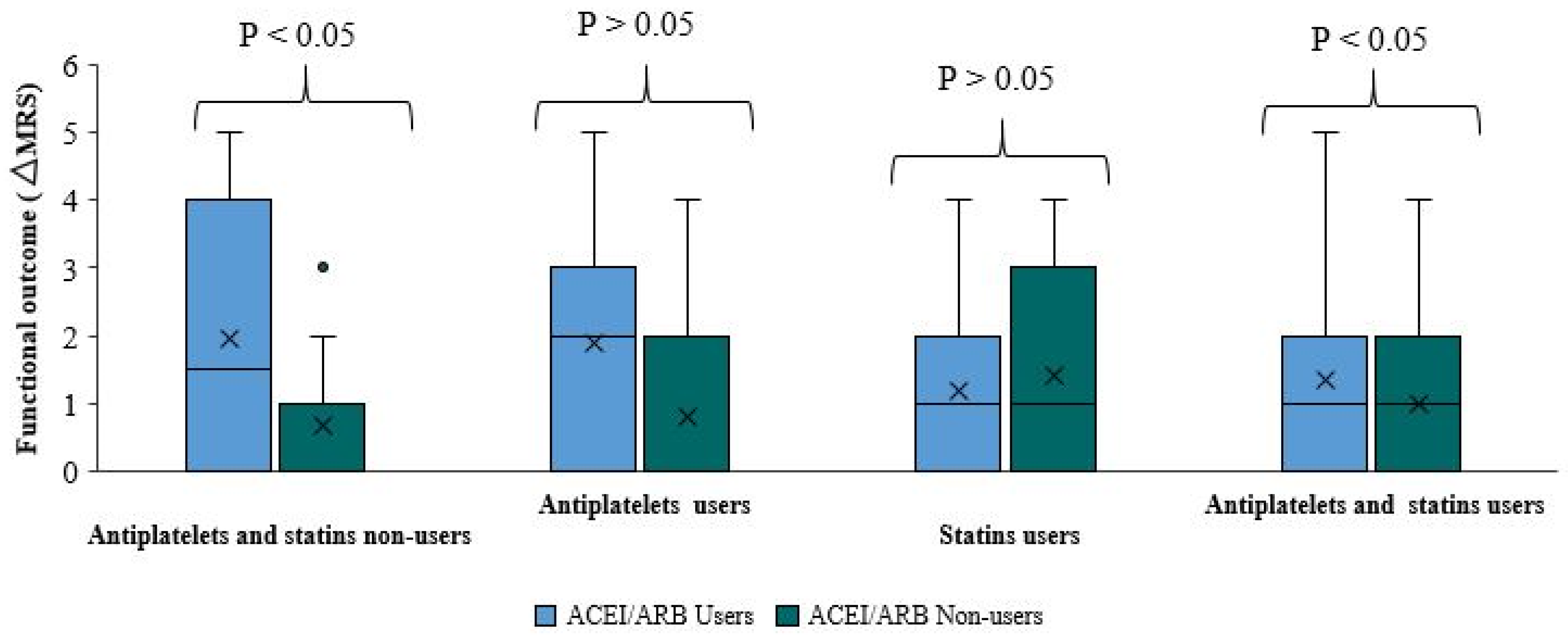

We got the same absolute indifference when comparing functional outcomes and ΔmRS between ACEI/ARB users and non-users among patients taking both antiplatelets and statins (p-value=0.094). The median ΔmRS of both sub-groups was equal. The ΔmRS in approximately 75% of patients in both sub-groups was less than two (

Figure 4).

Comparing functional outcomes and ΔmRS between ACEI/ARB users and non-users among patients not taking antiplatelets or statins is important. The functional outcome was significantly better among patients who did not use ACEI/ARB than those pre-treated with ACEI/ARB (p-value=0.023) (

Table 4,

Figure 4). The median ΔmRS score in ACEI/ARB users is higher by 1.5 points than the ΔmRS of ACEI/ARB non-users. Approximately 75% of ACEI/ARB users had a ΔmRS smaller than four. There is a better functional outcome and smaller ΔmRS among ACEI/ARB non-users, where 75% of the patients had ΔmRS less than one (

Figure 4). This research included a significantly large sample cohort to allow statistically valid and direct comparisons between ACEI/ARB users and non-users not taking antiplatelets or statins.

Moreover, there is no statistically significant difference in functional outcome when comparing ΔmRS between ACEI/ARB users and non-users among patients taking antiplatelets, or statins. Among patients taking antiplatelets (p-value=0.223), the median ΔmRS in ACEI/ARB users is higher by two points than the median ΔmRS of ACE/ARB non-users, reflecting a worse functional outcome among ACEI/ARB users. However, this finding is not statistically significant. The ΔmRS in approximately 75% of ACEI/ARB and antiplatelet users is less than three, compared to less than two in ACEI/ARB non-users. Among the subgroup of statin users, there is no statistically significant difference. The p-value was relatively high (0.656) when comparing the median ΔmRS between ACEI/ARB users and non-users. The ΔmRS of approximately 75% of ACEI/ARB users was less than 2, compared to less than 3 in ACEI/ARB non-users.

These statistically insignificant results cannot prove or deny any positive or negative effect of adding ACEI/ARB to antiplatelets or statins on the functional outcome of stroke. When combining ACEI/ARB usage to statins, a statistically unproven positive effect on functional outcome was observed. In contrast, an adverse effect was observed when ACEI/ARB usage was combined with antiplatelet treatment.

In summary, pre-stroke treatment with ACEI/ARB negatively impacts stroke severity and functional outcome, as shown with significant statistical indices when comparing overall ACEI/ARB users and non-users data. This was further statistically proven and confirmed with a direct comparison between ACEI/ARB users and non-users among patients not taking statins or antiplatelets, thus asserting to remove any possible positive impact of concomitant use of antiplatelets or/and statins. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant evidence of a positive effect on stroke severity or functional outcome when ACEI/ARB was added to statins and/or antiplatelets. The intersectional analysis and comparison among these subgroups favor a negative additive effect of ACEI/ARB (although the statistical indices were insignificant).

3.2.3. Further Outcomes: Comparison between ACEI and ARB

A few recent publications suggest a better neuroprotective effect of ARB over ACE, depending on the notion that the AT

2 receptor stimulation with AT

1 receptor blockade could contribute to protection against ischemic brain damage, at least partly due to an increase in cerebral blood flow and decrease in oxidative stress [

10].

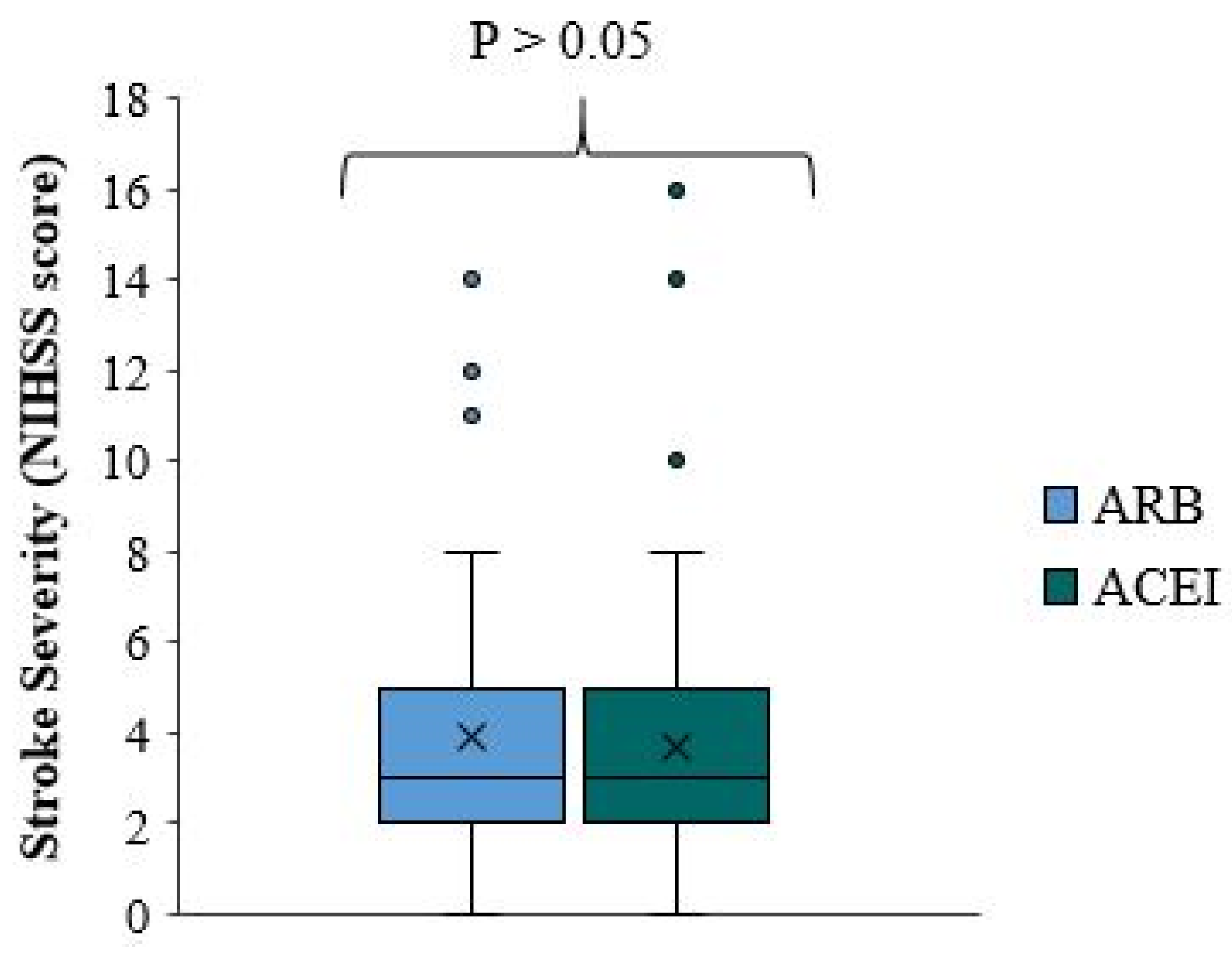

We separately compared stroke severity between all patients using ACEI and ARB. According to the result shown in

Figure 5, there is no significant difference in stroke severity between ACEI and ARB users (p-value=0.756). The median NIHSS score of ACEI and ARB users was roughly equal. The quartile distribution was similar in both groups, with approximately 75% having NIHSS scores of less than 5 in both ACEI and ARB users.

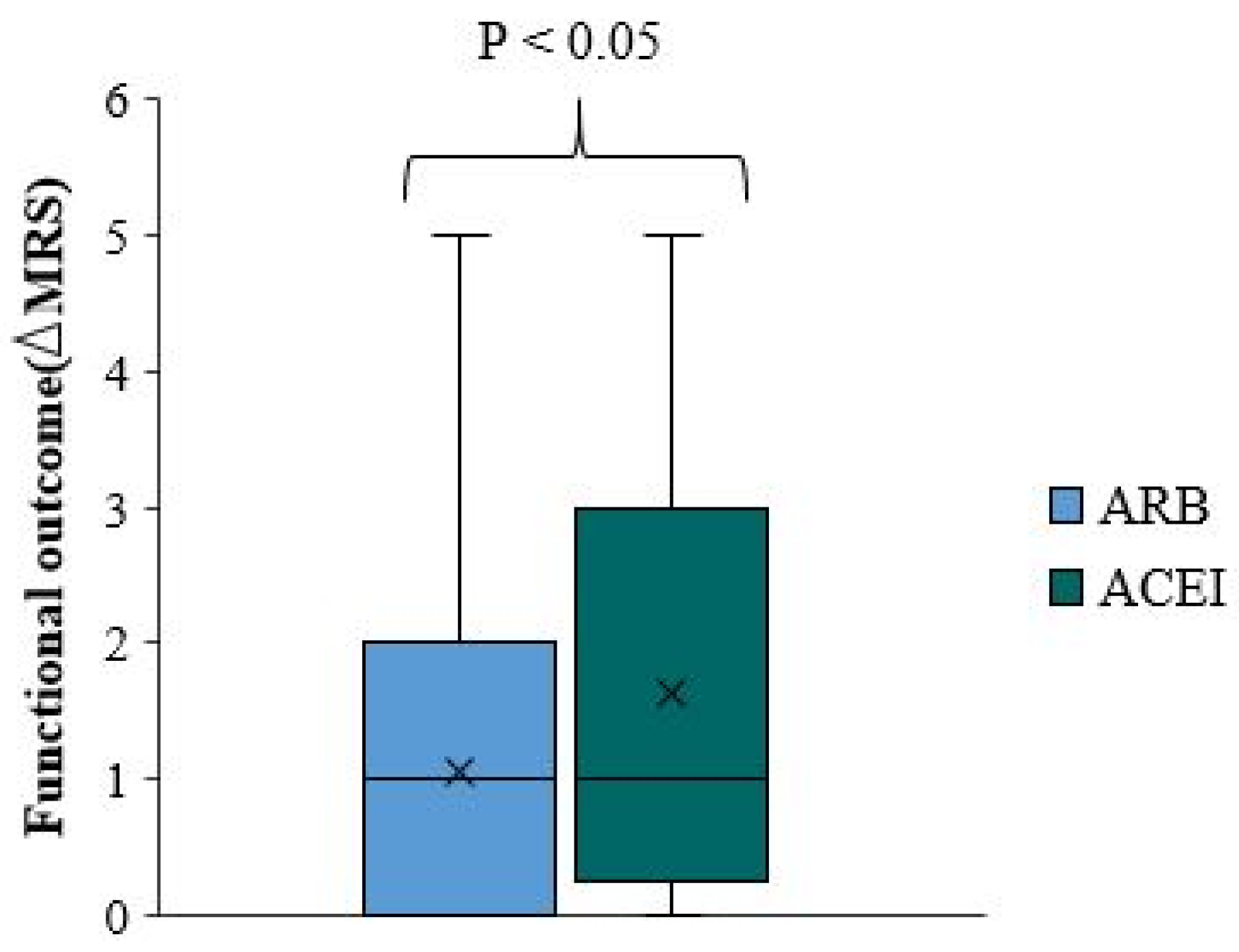

Similar results are observed when comparing functional outcomes (ΔmRS) between overall ACEI and ARB users. There was no significant difference in the ΔmRS median between ACEI and ARB users (p-value=0.015) (

Figure 6), as they were roughly equal. Nevertheless, the quartile distribution demonstrates a better outcome for ARB users, as 75% of ARB users had an ΔmRS less than two, while 75% of ACEI users had an ΔmRS less than three.

Although these results are statistically significant (p-value <0.05), there is no significant difference in the functional outcome between ACEI and ARB users as the median ΔmRS was roughly equal in both groups. The quartile distribution demonstrates a better functional outcome for ARB users with a ΔmRS less by one. These results must be validated in a larger cohort in prospective randomized studies.

3.2.4. Further Outcomes: Comparison of Functional Outcome and Stroke Severity between ACEI/ARB Users and Non-Users among Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients

Many experimental studies and medical textbooks mention the molecular and dynamic protective effect of ARB/ACEI among diabetic patients, particularly in preserving renal function.

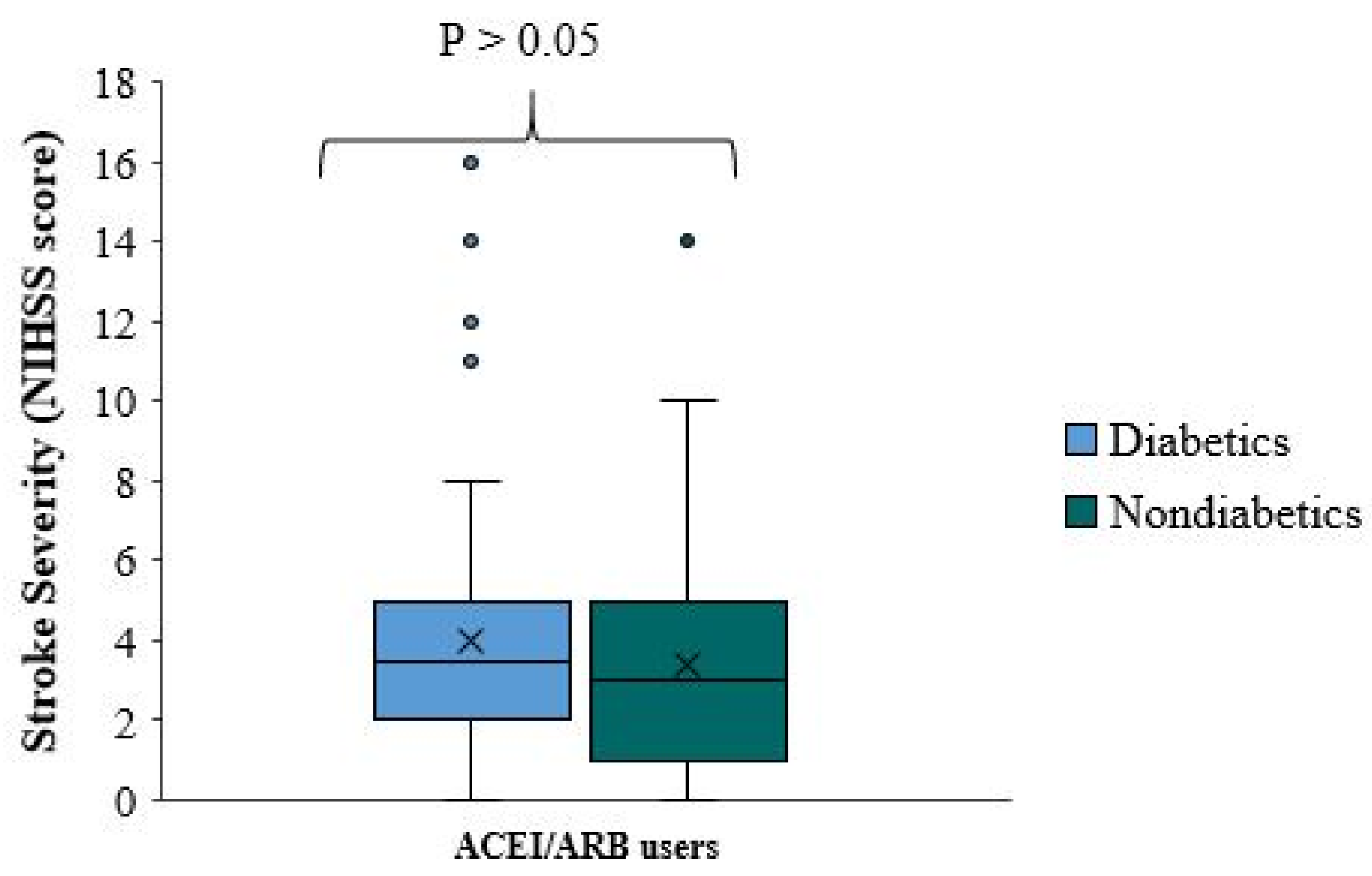

This study did not observe a significant neuroprotective effect when comparing stroke severity and functional outcome of ACEI/ARB among diabetic patients. There is no significant difference in stroke severity (NIHSS score) between diabetic and non-diabetic patients using ACEI/ARB (p-value=0.265). The median NIHSS score was roughly equal in both groups (

Figure 7). The quartile distribution was also similar, where the NIHSS score in approximately 75% of the patients is less than 5 in both sub-groups.

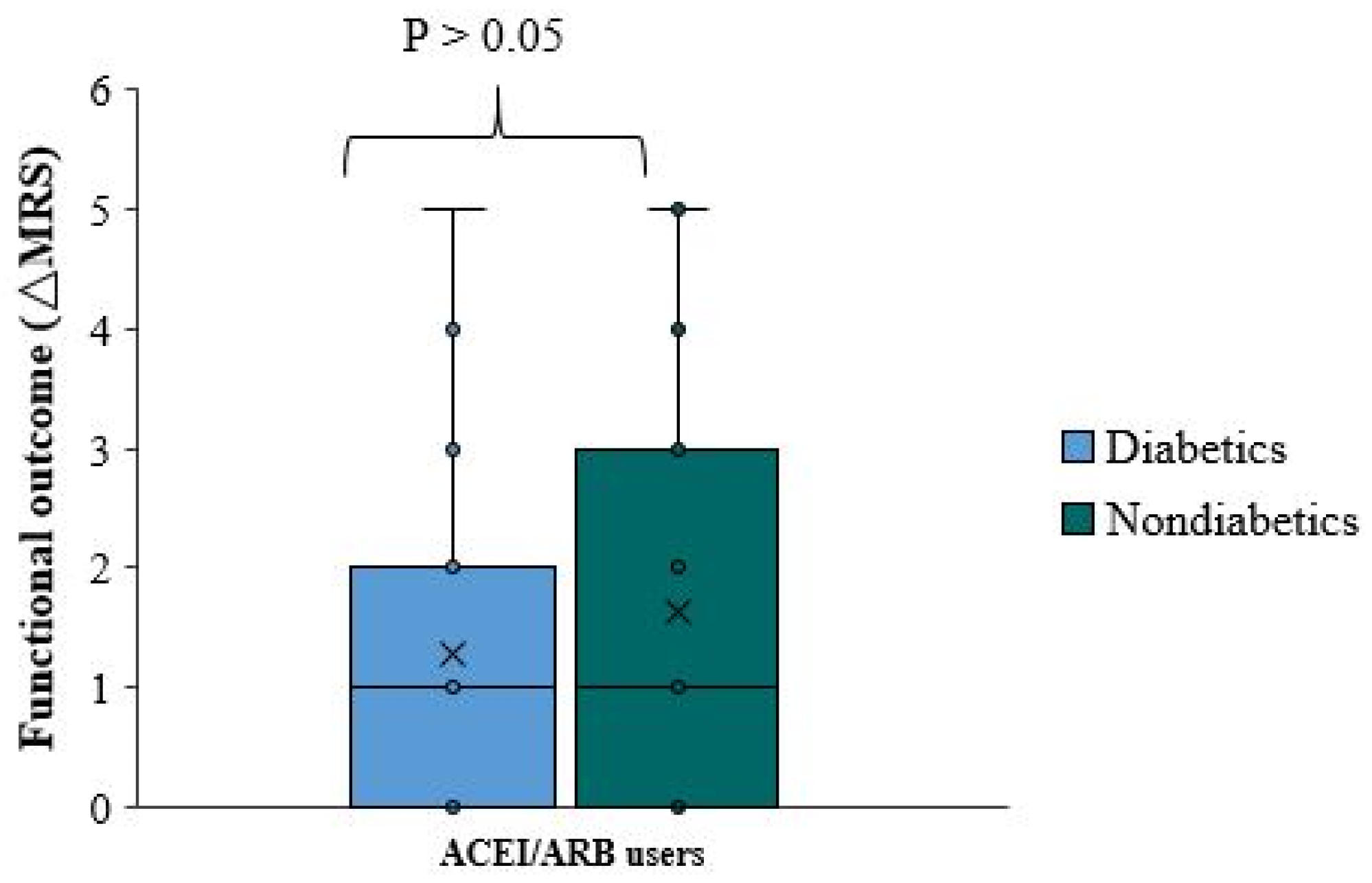

There is no significant functional difference (ΔmRS) between diabetic and non-diabetic patients using ACEI/ARB (p-value=0.656). The median (ΔmRS) was equal in patients with diabetes and those without diabetes (

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

In summary, pre-stroke treatment with ACEI/ARB is associated with worse stroke severity (at admission) and reduced functional outcome (at discharge). This difference was proven in a direct comparison among patients not taking statins or antiplatelets, thus abolishing any advantage of a positive effect that contributed to these medications. These results were similar in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. There was no significant difference between ACEI and ARB users in stroke severity and functional outcome. Moreover, there was no significant evidence of additional benefit when using ACEI/ARB in addition to antiplatelets and/or statins prior to the stroke.

When comparing the angiotensin-II-modifying agents, angiotensin-II-suppressing medications were associated with greater stroke severity. Previous studies have documented superior stroke protection with angiotensin-II-increasing agents following this observation. Several authors have attributed the greater cerebroprotection to activating angiotensin-II type 2 receptors [

10,

11,

12].

Several animal studies have shown that treatment with angiotensin-II increases before or after the induction of brain ischemia leading to improved survival [

13,

14]. This supports the hypothesis that ARB confers neuroprotection by selectively blocking angiotensin-II type 1 receptors leading to an upregulation and unopposed stimulation of the type 2 receptors. The type 2 receptors are also thought to be specifically upregulated in areas of ischemia, leading to enhanced collateral circulation to the regions with vascular compromise [

11]. This suggests that ACEI blunts the cerebroprotective effect by blocking the production of angiotensin-II entirely, inactivating both type 1 and type 2 receptors, potentially explaining increased stroke severity in the group pre-treated with ACEI.

The study’s retrospective design does not consider the adequacy of blood pressure control prior to stroke and the presence of end-organ damage, such as left ventricular hypertrophy. Both factors were previously shown to affect early stroke outcomes [

9]. Moreover, our study design did not allow us to assess the patients compliance with ACEI/ARB medication prior to the stroke or other medications.

Our study has some limitations due to the retrospective design and sample size. We cannot entirely exclude the possibility of residual confounding. For example, patients taking multiple medications can reflect that they have multiple risk factors for stroke and may suffer more severe strokes (confounding by indication). Conversely, these patients benefit from a closer follow-up with aggressive risk factor management and thus will benefit from a better outcome. We were also unable to collect information on the medication dosages, duration of treatment, and patient compliance. The relatively small number of samples does not allow us to test for possible differences among the various ACEIs/ARBs or dose regimens. Due to incomplete data, we could not control for potential confounders, such as orthopedic comorbidities and limitations or pre-morbid cognitive states that may affect NIHSS, mRS, or both.

This study has limitations unrelated to the retrospective design and sample size. The length of hospitalization was not assessed or intersectionally analyzed. A better mRS and functional outcome can be partially attributed to the natural, spontaneous recovery, which may be more prominent in more extended hospitalization. The confounding effect of the ischemic stroke subtype was not considered when the interplay between antiplatelets and/or statin use and stroke severity was evaluated. We did not analyze the possible differences in ACEI/ARB benefits on stroke severity in the various etiological stroke subgroups. Imaging surrogates of severity could be more advantageous and accurate compared to clinical scales while seeking a slight benefit due to their better interexaminer reliability and higher statistical power. We only analyzed the first ischemic stroke and have no evidence regarding patients with previous ischemic strokes, nor those with a hemorrhagic stroke. We did not analyze data referring to post-stroke use of ACEI/ARB. Therefore, consequently, we cannot draw any conclusion regarding the long-term effect on outcomes induced by their continuation.

5. Conclusions

Pre-stroke usage of angiotensin-II-decreasing agents, such as ACEI and ARB was associated with an increased initial stroke severity at admission and worse functional outcome at discharge. However, because of its retrospective nature, our study can only be interpreted as suggestive; thus, prospective studies of these medications on ischemic stroke severity and early outcomes are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Writing this article would not have been possible without the support and assistance of numerous individuals and resources. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to all those who have contributed to the completion of this article. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the contributions of my colleagues and fellow researchers who provide feedback and suggestions for improvement. Their input has been instrumental in strengthening the quality and rigor of this work. In addition, I would like to express my appreciation to the academic community of Tzafon and Shaare Zedek medical centers for their continuous support and scholarly resources. In conclusion, I am indebted to all those who have played a role in the development and completion of this article. Their contributions and support have been invaluable, and I am truly grateful for their assistance.

Abbreviations

| ARB |

angiotensin receptor blocker |

| ACEI |

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor |

| HTN |

hypertension |

| mRS |

Modified ranking scale |

| NIHSS |

national institute of health stroke scale |

References

- Sanossian N, Saver JL, Rajajee V, Selco SL, Kim D, Razinia T, Ovbiagele B. Premorbid antiplatelet use and ischemic stroke outcomes. Neurol. 2006, 66, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung JM, Choi J, Eun MY, Seo WK, Cho KH, Yu S, Oh K, Hong S, Park KY. Prestroke antiplatelet agents in first ever ischemic stroke. Neurol. 2015, 84, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi JC, Lee JS, Park TH, Cho YJ, Park JM, Kang K, Lee KB, Lee SJ, Ko Y, Lee J, Kim JT, Yu KH, Lee BC, Cha JK, Kim DH, Lee J, Kim DE, Jang MS, Kim BJ, Han MK, Bae HJ, Hong KS. Effect of pre-stroke statin use on stroke severity and early functional recovery: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim M, Savitz S, Linfante I, Caplan L, Schlaug G. Effect of pre-stroke use of ACE inhibitors on ischemic stroke severity. BMC Neurol. 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu AYX, Keezer MR, Zhu B, Wolfson C, Cote R. Pre-stroke use of antihypertensives, antiplatelets, or statins and early ischemic stroke outcomes. Cerebrovas Dis. 2009, 27, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar S, Savitz S, Schlaug G, Caplan L, Selim M. Antiplatelets, ACE inhibitors, and statins combination reduces stroke severity and tissue at risk. Neurol. 2006, 66, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greisenegger S, Mullner M, Tentschert S, Lang W, Lalouschek W. Effect of pretreatment with statins on the severity of acute ischemic cerebrovascular events. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004, 221, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vibo R, Kõrv J, Roose M. One-year outcome after first-ever stroke according to stroke subtype, severity, risk factors and pre-stroke treatment. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007, 14, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redon J, Cea-Calvo L, Lozano JV, et al: Differences in blood pressure control and stroke mortality across Spain: PREV-ICTUS Study. Hypertension 2007, 49, 799–805. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysant SG: Possible pathophysiologic mechanisms supporting the superior stroke protection of angiotensin receptor blockers compared to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: clinical and experimental evidence. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2005, 19, 923–931. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier A, Messerli FH, Archard JM, Fernandez L: Cerebroprotection mediated by angiotensin II: a hypothesis supported by recent randomized clinical trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 1343–1347.

- Epstein BJ, Gums JG: Can the renin-angiotensin system protect against stroke? A focus on angiotensin II receptor blockers. Pharma-cotherapy 2005, 25, 531–539. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai WJ, Funk A, Herdegen T, Unger T, Culman J: Blockade of central angiotensin AT 1 receptors improves neurological outcome and reduces expression of AP-1 transcription factors after focal brain ischemia in rats. Stroke 1999, 30, 2391–2399. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez LA, Caride VJ, Strömber C, Näveri L, Wicke JD: Angiotensin AT 2 receptor stimulation increases survival in gerbils with abrupt unilateral carotid ligation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1994, 24, 937–940. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).