1. Introduction

Globally, one of the fastest growing industries is tourism [

1], which can be either domestic or international, and revenue from this industry supports national economies. However, it is important to consider the potential for infectious disease transmission from tourists to the populations in their destination countries, which may be a detrimental side effect of tourism [

2]. While it is likely that the majority of tourists partake in little or no sexual activity, the sexual behavior of tourists can play a role in the transmission and spread of disease, especially when unprotected sexual activity takes place[

3,

4]. Therefore, tourists may play an important role in the spread of disease to the host nation’s population, whether the sexually transmitted infection (STI) was obtained in the tourist’s country of residence/home country or the tourists contracted it during their trip [

1,

2]. Tourism is inextricably linked to the transmission of diseases that are infectious.

Tourism has been one of the most significant industries in Malaysia in recent decades, and several studies have suggested that touristic regions are linked to increased HIV risk in the nation. Ketshabile et al. (2007) investigated how HIV/AIDS affects Southern African tourism, with specific reference to the tour operators (13). By conducting a qualitative study on Dominican Republic policymakers, Padilla et al. (2012) investigated the policy environment for tourism-related HIV prevention in the Caribbean industry [

6]. Padilla et al. (2010) argued that the direction of future studies will be influenced by the change in environmental perspective on sexual health in Caribbean tourist destinations and HIV/AIDS cases [

7]. A study by De Matos et al. (2013) indicated that, in Central Brazil, most sexually transmitted diseases have increased due to females that engage in the sex trade through prostitution to tourists [

8], and Guilamo-Ramos et al. (2013) studied the efficient health intervention design for HIV prevention among tourists using the family to combat the HIV epidemic as a means for [

9].

Mathematical models have become indispensable tools that provide a thorough understanding for epidemiologist researchers [

10,

11,

12]. The model used in this study is based on the SIR (Susceptible-Infective-Recovery/Removal) model, which has been used in several studies [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Recently, disease spread models have investigated the dynamics of how tourists have affected HIV transmission [

17,

18,

19]. Other research has used simulation to determine the effect of the tourism control approach on the spread of HIV among those who travel as tourists [

20,

21]. Although many of these issues are not well understood, they are nonetheless potentially important. To the authors’ knowledge, there exist relatively few studies on the impact of tourism on HIV/AIDS using mathematical models. Although some examples exist [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], these models did not take the following into account: i) children born to infected parents may be carriers of the disease, and ii) the susceptible class should have a rate of birth that is independent of vertical transmission; and finally, iii) the potential for direct contact between tourists and HIV/AIDS -positive individuals. In this paper, the impact on the occurrence of HIV and AIDS in tourism incidence in Malaysia will be investigated using epidemiological data over the period of 12 years with consideration for newborns infected with HIV [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data

Malaysian epidemiological data [

33] on clinically confirmed HIV-positive, AIDS incidence, and tourist entries into Malaysia from 1986 to 2011 were used to develop and validate the epidemiological model. Three people acquired HIV in 1986, making up the original

compartment (HIV cases), and one person developed AIDS because of their HIV infection (making up the

compartment). There were 16,329,396 members of the susceptible

compartment, which means there were 16,329,400 people in the entire population and there were 3,200,000 tourists in 1986 [

34]. And information based on the reported cases by the Ministry of Health, Malaysia [

35].

2.2. Description of the model equation

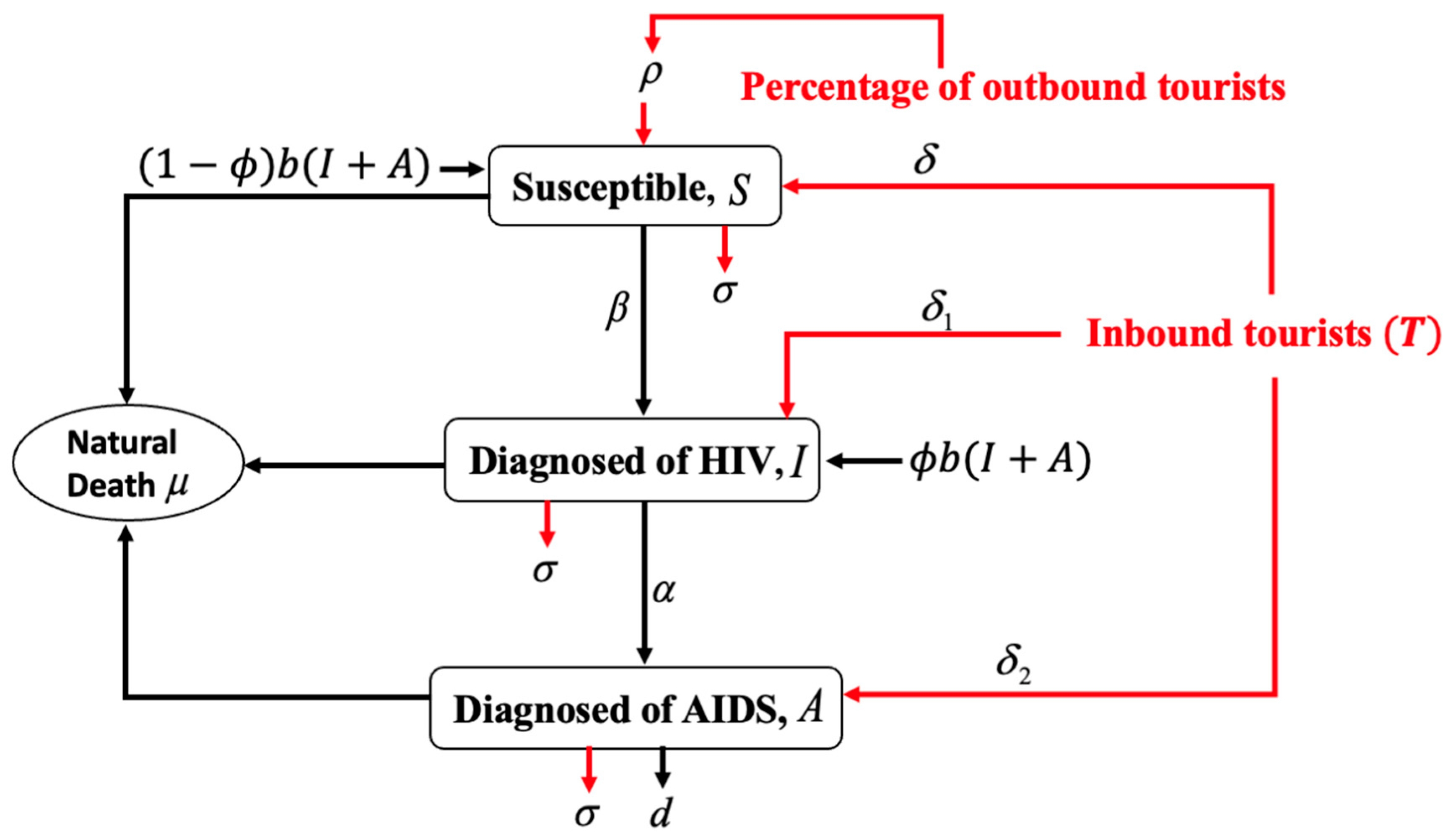

Figure 1 describes the proposed model compartments the human population, represented by

, to susceptible S(t), HIV-positive people who are clinically tested

, those with AIDS

, and tourists

Those in the tourism compartment arrive in the host nation from all over the world, and their interactions take the shape of sexual interactions and other activities that contribute to the occurrence of HIV/AIDS and its spread [

19].

The model shown in

Figure 1 implies that HIV-positive newborns enter the HIV class at a rate of

, for which we assume that

and

are sexually active,

, and are HIV-positive newborns, where

is the percentage of newborns that are HIV-negative [

36]. A fraction of

will considered to be susceptible. The likelihood of HIV transmission by sexual contact or needle sharing is known as the susceptibility to infection at rate

. Here,

the natural death is supposed to be constant across all compartments. The parameter

denotes additional AIDS-related death rates, while the

parameter indicates the rate of transfer of HIV-positive compartment members into the AIDS compartment. The tourists will migrate/move to the susceptible, HIV, and AIDS compartments at the rates of

,

, and

, and tourists are leaved each compartment at the rate of

. We considered the proportion of domestic tourists (nationals) who travel abroad and contract HIV before returning,

[

19].

2.3. Calculating of reproduction number

All the model’s dependent parameters and variables are assumed to be non-negative. From equations (1)-(3), when there is the absence of HIV-positive and AIDS disease,

. However, under the dynamics described by equations (1)-(3), the region

, is positively invariant. Therefore, for the initial starting point

; the trajectory lies in

. Therefore, we can restrict our analysis to the region

. Existence, uniqueness, and continuation results for systems (1)-(4) hold in this region as described [

36,

37]). It is possible to examine whether the disease-free equilibrium has the property of asymptotic stability,

, adopting a next-generation operator strategy [

38,

39,

40]. Specifically, where

matrix represents the new infection terms, and

matrix represents the transition terms, respectively, such that:

By taking the inverse of matrix

and multiplying it by the matrix

, the following result is obtained:

From the disease-free equilibrium, and by substituting it into . The reproduction number of the proposed model is . The reproduction number, which measures how contagious infectious illnesses are, is the anticipated number of new HIV-positive cases that a typical infected person introduces into a group with a specific percentage of protection.

Firstly, we looked at how the tourism industry affected HIV and AIDS pandemic in Malaysia. Using our national suggested model, we then concentrated on comprehending the epidemic, projecting evolutionary tendencies, and pinpointing the crucial epidemiological factors that fuel the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

3. Results and discussion

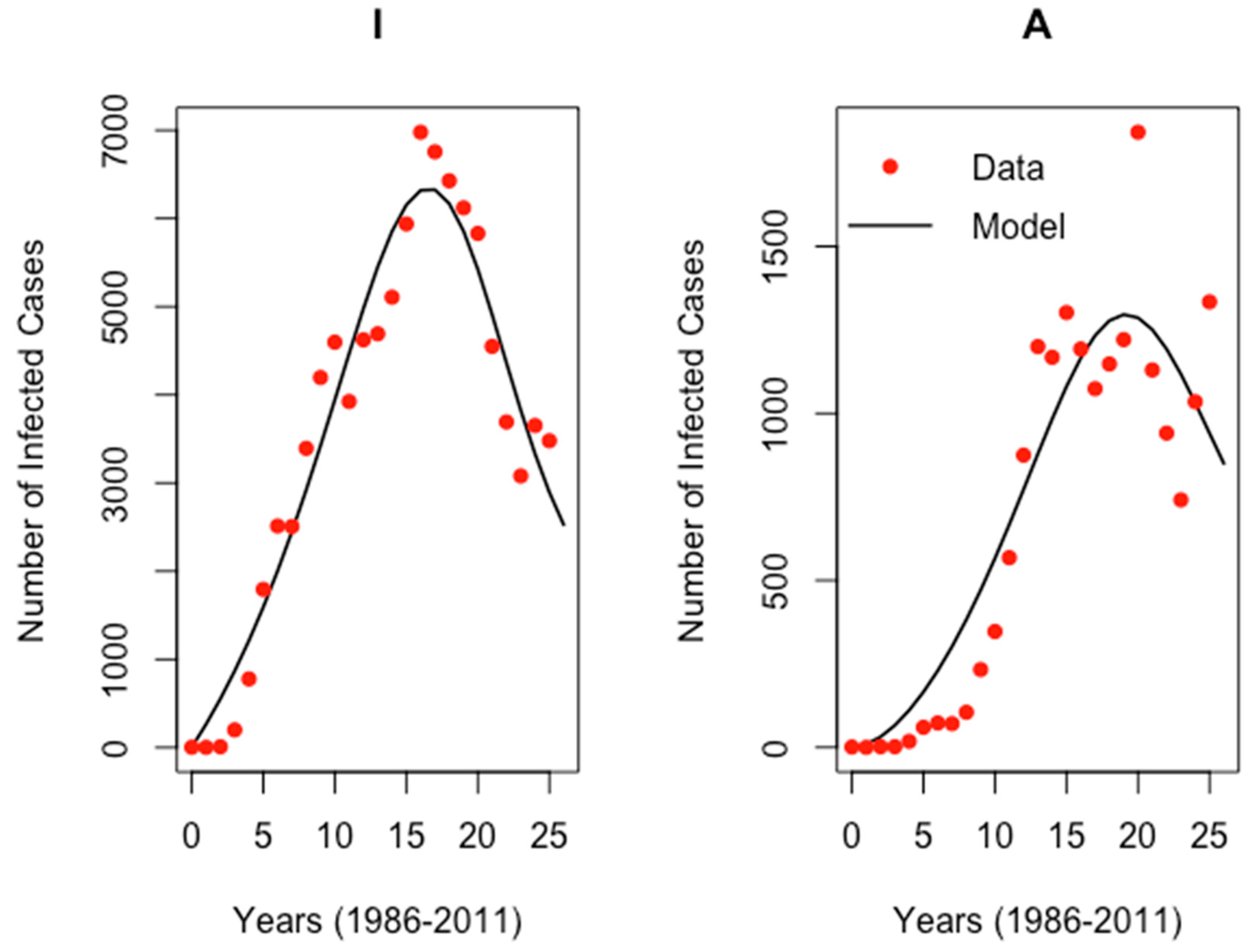

After a model has been fitted to the data, the parameter estimates that were determined by the best fit are shown in

Table 1, which were used to determine the reproduction number.

Figure 2 shows a comparison between the observed yearly reported HIV and AIDS cases with fitted lines obtained through simulations during the 25-year (1986-2011). Evaluating the plot of the graph by comparing its performance means that the model can generate good parameter estimates and can be used for predictions in future studies.

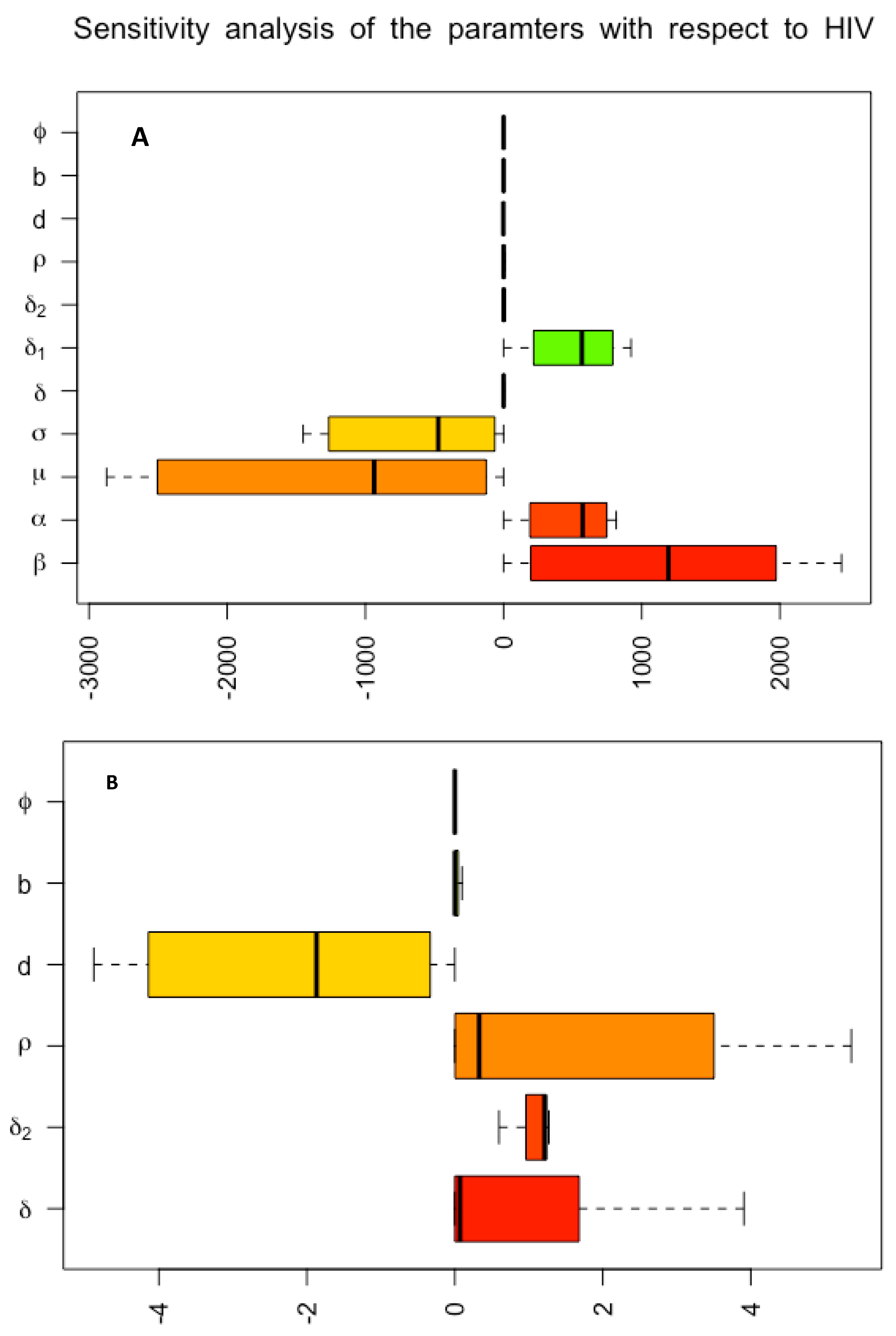

Then, to determine the burden of the disease and the effect of tourism, we investigate how sensitive the model parameters are with their impact on the spread of HIV. The analysis is required to pinpoint the parameters of the model that have a big impact on results and assess how resilient the model is to parameter values. Each variable’s sensitivity to parameters is determined as they change over time, and the variance of each variable is then plotted as a box plot after outliers have been removed.

Figure 3 depicts the sensitivity analysis of important factors in relation to HIV populations.

Figure 3A illustrates how the prevalence of HIV tends of tourists who came in with HIV infected rate

was higher. The rationale is that as the population of Malaysia increases, the likelihood of transmission between tourists and people with HIV increases significantly. Sex between tourists is more likely to increase as well because the HIV population is growing alongside Malaysia’s population. This is because the probabilities of transmission per susceptible have a positive effect on the HIV population. It’s noteworthy to note that the rapid growth of the tourist population in Malaysia has led to an increase in HIV spread.

Figure 3B shows how the percentage of the national tourists who returns to the country with HIV (

) also has an impact on the spread. The rate of a fraction of newborn infected with HIV (

) has less impact on the spread of HIV. Because we assumed an introduction of intervention measure

to ensure that not all newborn babies might probably be born with HIV.

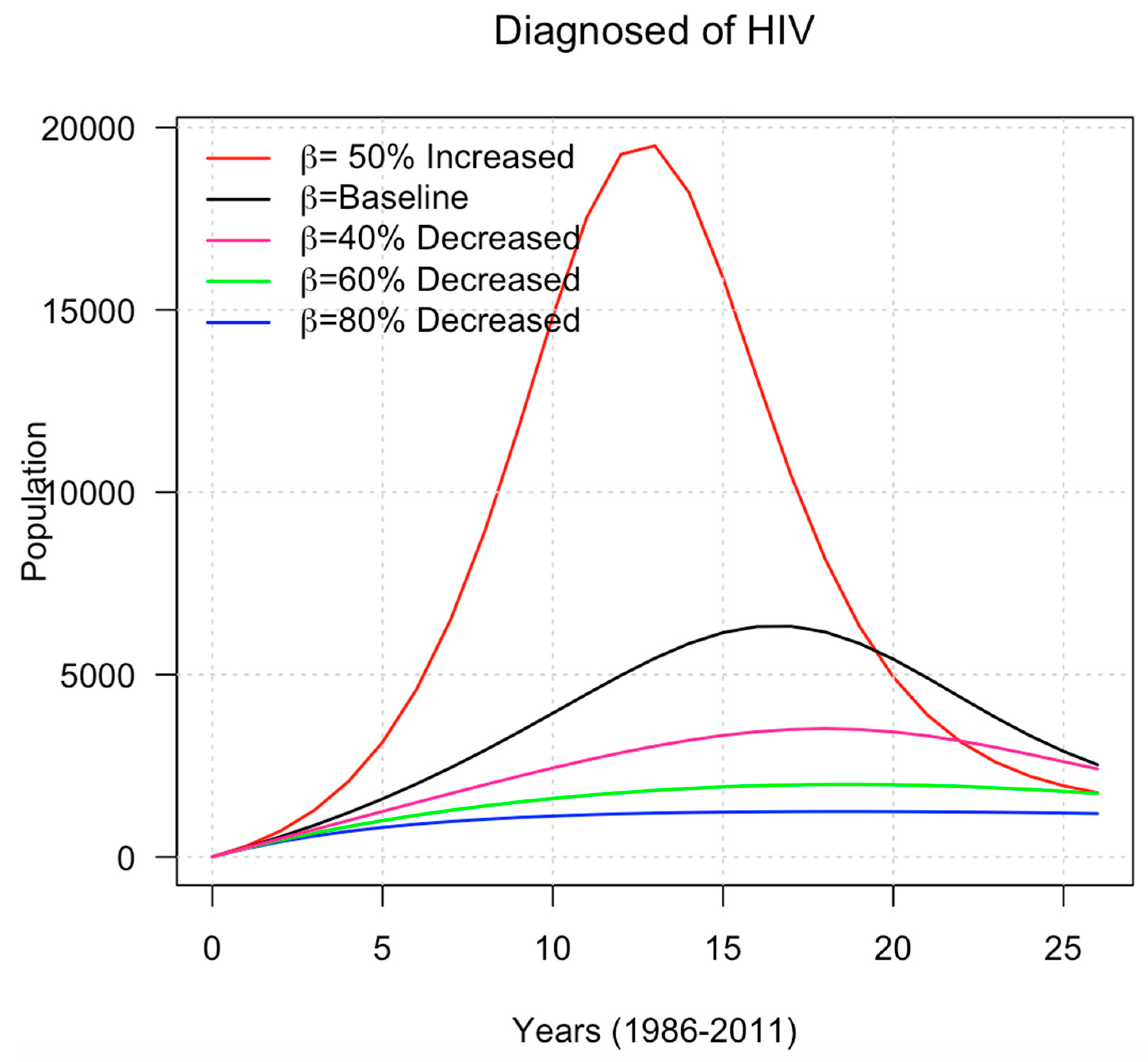

Additionally, we looked into how changes in

and

impacted Malaysia’s population in terms of HIV spread. The dynamics of the susceptible population were shown to be greatly impacted by increasing the probability of transmission per susceptible

, as was the case with the susceptible to prevent infection, as shown in

Figure 4.

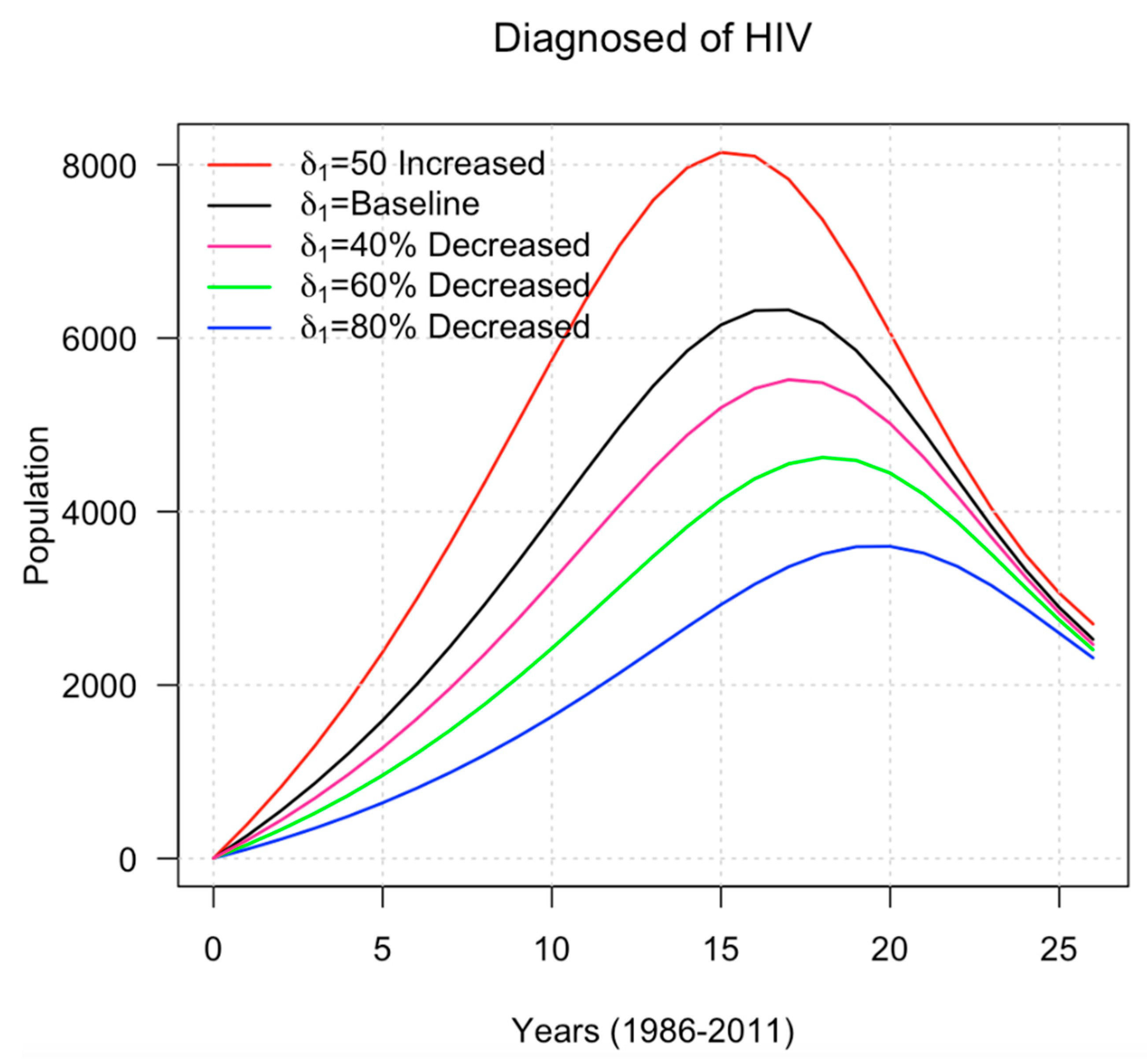

In

Table 2, increasing the baseline

(transmission probability) by 50%, for example, will result in approximately 138958 HIV cases (34%) in the Malaysian population as compared to the baseline probabilities of transmission per susceptible at 98069 HIV cases. Whiles, a reduction in

shows a drastic decrease in the infected individual with HIV cases as far as an 80% decrease in the baseline will be 27352 HIV cases. With the infectious populations, a similar pattern was seen. The effects of

on HIV population growth are shown in

Figure 5, tourist-infected populations decreased as

decreased with less.

As shown in

Table 3, for example, a 50% rise in the baseline of

will lead to about 125071 additional cases of HIV in the Malaysian population as opposed to the baseline of 98069 cases. With the baseline number of HIV cases at 54926, the reduction in

indicates a sharp decline in the number of HIV individuals.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we proposed and examined an epidemiological model including an influx of tourists. As many nations throughout the world have benefited economically from tourism, plans must be made for the impact this will have on the spread of disease in the future. Consideration must be given to how well tourists can sustain Malaysia’s current economic situation. However, it is also important to consider more than just the decline in HIV incidence when assessing how tourism affects HIV prevention strategies in Malaysia. We presented a population-level mathematical model to investigate the validity of the tourist factor and prevention measures to reduce HIV cases in Malaysia. To assess whether the spread of infectious diseases is stable or unstable inside Malaysia depending on the influx of tourists, we first calculated the reproduction number

, a contagiousness threshold. Epidemiologically, the transmission will wane or stop when

. If

, on the other hand, it is anticipated that the number of infected people will rise. Our findings demonstrate that the steady-state absence of disease is stainable because

was 0.0017, based on the estimated parameters (

Table 1). These findings demonstrate the high prevalence of HIV and AIDS in Malaysians. From a public health perspective, this is good news because the main objective is to achieve a steady infection at an equilibrium free of disease.

To determine the impact of the different parameters on HIV transmission with the influx of visitors, a thorough sensitivity analysis was carried out. The prevalence of HIV of tourists who came in with HIV infected rate

was higher and as well as the probabilities of transmission per susceptible

(

Figure 3A). As shown in

Table 3, in contrast to the baseline of 98069 cases, a 50% increase in the baseline of

will result in approximately 125071 extra cases of HIV in the Malaysian population. The decrease in

shows a substantial reduction in the number of people living with HIV, with the baseline number of HIV cases being 54926.

In terms of percentage, the difference between the rate of tourists moving to the susceptible and the rate at which tourists leave the susceptible is 12% (i.e.,

). This may be due to the fact most of the foreigners who enter Malaysia as tourists stay there for a couple of periods. However, the percentage of the national tourists who returns to the country with HIV is approximately 14% (

Table 1) and this will have policy ramifications for communities most at risk. The fraction of newborn babies who are infected with HIV,

is 8.5610x10

-7 and will give the estimation of the newborn as

.

Finally, it is important to recognize the limitations of this study. The findings could be negatively impacted by the dearth of comprehensive epidemiological data from the outbreak to this point. Nevertheless, the estimated parameters

-3,

-4, and

-8 suggest that tourism has a strong effect on HIV transmission in Malaysia (

Table 3). Given this, there is a need for the country to take significant steps in quantifying the trend and magnitude of the tourism and to develop platforms that will assist public health officials to incorporate control strategies. The average number of days stayed in Malaysia was incorporated into the proposed model as a parameter. However, in reality, the period a tourist stays in Malaysia will vary significantly.

Despite these drawbacks, our findings strongly suggest that visitors to Malaysia have contributed to HIV and AIDS infection. To reduce the effective HIV and AIDS spread, it may be necessary to strengthen the control of tourists. Many more comparable quantities can be investigated if they can be expressed in relation to the underlying parameters of the proposed model.

Author Contributions

OOA designed the study, OOA processed the data, performed the analysis, and prepared the tables and figures. OOA, P.R and BC aided in interpreting the results. OOA took the lead in writing the manuscript with assistance from PR, and BC. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Funding

The research work was self-sponsored by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results presented in this manuscript is available as stated above.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Bauer, I. The health impact of tourism on local and indigenous populations in resource-poor countries. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 2008; 6Published online: 2008. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, I. Understanding sexual relationships between tourists and locals in Cuzco/Peru. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 2007; 5Published online: 2007. [CrossRef]

- Wright, ER. Travel, tourism, and HIV risk among older adults. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2003; 33Published online: 2003. [CrossRef]

- Marrazzo, JM. Sexual tourism: Implications for travelers and the destination culture. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2005.

- Ketshabile LSimeon. HIV and AIDS as a threat to Southern African tourism. Cape Peninsula University of Technology. 2007.

- Padilla M, Reyes A, Connolly M. Examining the policy climate for HIV prevention in the Caribbean tourism sector: a qualitative study of policy makers in the Dominican Republic. Health Policy and Planning 2012; Published online: 2012.

- Padilla, MB. HIV/AIDS and tourism in the Caribbean: An ecological systems perspective. American Journal of Public Health 2010; 100Published online: 2010. [CrossRef]

- de Matos, MA. Vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections in women who sell sex on the route of prostitution and sex tourism in central Brazil. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 2013; 21Published online: 2013. [CrossRef]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V. HIV sexual risk behavior and family dynamics in a Dominican tourism town. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2013; 42Published online: 2013. [CrossRef]

- Nyabadza F, Mukandavire Z. Modelling the HIV/AIDS epidemic trends in South Africa: Insights from a simple mathematical model. Nonlinear Analysis: Real 2011; Published online: 2011.

- Bacaër, N.; Abdurahman, X.; Ye, J. Modeling the HIV/AIDS epidemic among injecting drug users and sex workers in Kunming, China. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2006; 68Published online: 2006. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, JM.; Li, J.; Ann Stanley, E. The differential infectivity and staged progression models for the transmission of HIV. Mathematical Biosciences 1999; 155Published online: 1999. [CrossRef]

- Kermack, WO.; McKendrick, AG. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics-III. Further studies of the problem of endemicity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991; 53: 89–118. 8: 53.

- Kermack, WO; McKendrick, AG. Contributions to the mathematical theory of epidemics-II. The problem of endemicity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991; 53: 57–87.

- Kermack, WO.; McKendrick, AG. A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences The Royal Society, 1927; 115: 700–721.

- Keeling., MJ.; Rohani, P. Modeling Infectious Diseases through Contact Networks. Press PU, ed. 2008.

- Apenteng, O.O.; Ismail, N.A. Modelling the impact of international travellers on the trend of HIV epidemic. Lecture Notes in Engineering and Computer Science. 2014.

- Apenteng, O.O.; Ismail, N.A. Modeling the impact of international travellers on the trend of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Transactions on Engineering Technologies: World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2014. 2015.

- Apenteng, OO. Assessing the effects of tourism on the spread of HIV and AIDS in Malaysia using susceptible infected removed models.

- Jamal, T.; Budke, C. Tourism in a world with pandemics: local-global responsibility and action. Journal of Tourism Futures 2020; 6Published online: 2020. [CrossRef]

- Suess, C. Using the Health Belief Model to examine travelers’ willingness to vaccinate and support for vaccination requirements prior to travel. Tourism Management 2022; 88Published online: 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.; Haour-Knipe, M.; Aggleton, P. Mobility, sexuality and AIDS. Mobility, Sexuality and AIDS. 2009.

- George, A.; Richards, D. A Paradigm Shift in the Relationship between Tourists and their Hosts: The Impact on the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Trinidad and Tobago. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism 2012; 11Published online: 2012. [CrossRef]

- Phelan, KV. Elephants, orphans and HIV/AIDS: Examining the voluntourist experience in Botswana. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 2015; 7Published online: 2015. [CrossRef]

- Orisatoki, RO.; Oguntibeju, OO.; Truter, EJ. The contributing role of tourism in the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Caribbean. Nigerian journal of medicine : journal of the National Association of Resident Doctors of Nigeria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, S.; Hasbún, J.; Butler De Lister, M. Protecting paradise: Tourism and AIDS in the Dominican Republic. Health Policy and Planning 1998; 13Published online: 1998. [CrossRef]

- Laar, A.K. Predictors of fetal anemia and cord blood malaria parasitemia among newborns of HIV-positive mothers. BMC Research Notes 2013; 6Published online: 2013. [CrossRef]

- Domingues, RMSM.; Saraceni, V.; Do Carmo Leal, M. Mother to child transmission of HIV in Brazil: Data from the ‘Birth in Brazil study’, a national hospital-based study. PLoS ONE 2018; 13Published online: 2018. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raya, B. Transfer of maternal antimicrobial immunity to HIV-exposed uninfected newborns. Frontiers in Immunology, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bitnun, A. Early initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 Infected newborns can achieve sustained virologic suppression with low frequency of CD4+ T cells carrying HIV in peripheral blood. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2014; 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eki-Udoko, FE. Prevalence of congenital malaria in newborns of mothers co-infected with HIV and malaria in Benin city. Infectious Diseases 2017; 49Published online: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dzanibe, S. Reduced transplacental transfer of group b streptococcus surface protein antibodies in HIV-infected mother-newborn dyads. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2017; 215Published online: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ngadiman ari. Malaysia: The Global AIDS Response Progress Report 2012, 2012.

- Nicholas, B. The impact of the existence of ulu skrang roads upon tourism activities and rural livelihood, 2005.

- oint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic, UNAIDS, 2013.

- Apenteng, OO.; Ismail, NA. A markov chain monte carlo approach to estimate AIDS after HIV infection. PLoS ONE, 2015; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyabadza, F.; Mukandavire, Z. Modelling HIV/AIDS in the presence of an HIV testing and screening campaign. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical Biosciences, 2002; 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, JAP.; Roberts, MG. The construction of next-generation matrices for compartmental epidemic models. 2009; Published online: 2009. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, MG.; Heesterbeek, JAP. Model-consistent estimation of the basic reproduction number from the incidence of an emerging infection. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 2007; 55, 803–816. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).