The effects of incarceration on youths’ sense of identity and music-based rehabilitation: An exploratory pilot study

Incarcerated populations often fall victim to labeling theory, which argues that individuals who are labeled as delinquents are more likely to engage in delinquent behavior. These individuals are exposed to what is known as disintegrative shaming, and their societal interactions encourage further criminal behavior (Braithwaite, 1989). They struggle to reintegrate into the community and obtain meaningful employment which leads to a withdrawal from conformity and bitterness towards the institutions that ostracized them (Ascani, 2012). The deviant label assimilates into their identity and informs their future behaviors; thus, reformation of this self-perception is crucial.

Numerous studies demonstrate how music programs can impact identity and behavior among incarcerated populations, eliciting improvements in self-esteem, well-being, and overall quality of life within the facility (Chen et al., 2015; Chong & Yun, 2020; Cohen, 2012; Hickey, 2018; Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020; Kennedy, 1998; Mota, 2012). Programs implemented with incarcerated youth found differences in self-concept and resilience (Chong & Yun, 2020), competence and positive affect (Hickey, 2018), and reductions in antisocial behaviors (Wolf & Holochwost, 2016). Wolf and Holochwost (2016) emphasize use of a dynamic systems perspective since their analyses yielded different results in the two sites where data was collected. Despite geographical proximity, variations in environmental context moderated the efficacy of the music program; however, longitudinal analyses suggest that engagement in the arts improves academic achievement levels and increases aspirations to obtain a college education in at-risk youth (Catterall et al., 2012). Cohen (2019) also found great success in transforming the self-perception of incarcerated men through a prison choir program. Notably, one participant wrote,

Before the choir, I saw myself as a drug addict, a “lifer” and a convict. I didn’t like or respect myself, and I never thought that my life would have any meaning or value to anyone other than my family. Now I see myself through different eyes. I’m valuable because I’m a human being. I may never get out of prison, but I can be useful while in prison because I have a voice and I’m capable of using that voice to sing, laugh, and speak out on topics that matter. I know this because of choir. (Cohen, 2019, p. 109S)

Despite having a life sentence, participating in the choir program was able to transform his identity. Cohen (2012, 2019) sought to gain a broad understanding of how music was transformative with an emphasis on self-esteem. Other studies investigating incarcerated adults took a similar approach but measured different outcome variables such as social/group identity (Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020). Qualitative interviews illuminate themes of community within the group and momentarily forgetting their reality of imprisonment while engaging in these programs (Kyprianides & Easterbrook; Mota, 2012). While engaging in music programing, participants did not view themselves as inmates, implying a greater sense of autonomy in an environment which restricts it (Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020). This suggests an intersection between labeling theory and music programming. Therefore, understanding the psychological experience of incarceration informs not only music-based rehabilitation, but rehabilitative programming in its entirety.

Principally, this paper investigates how the identity can be defined, measured, and changed using approaches involving music. Research investigating the relationship between youth incarceration and identity is limited (Abrams & Hyun, 2009; Chassin & Stager, 1984; Kroska et al., 2016; Peacock, 2006) and differing theoretical approaches are taken to establish this relationship. Identity is operationalized through the labelling theory (Chassin & Stager, 1984; Kroska et al., 2016), Erik Erkison’s stages of identity development (Peacock, 2006), and identity negotiation, defined as the identity transition that occurs when institutionalized (Abrams & Hyun, 2009). It is worth noting that these studies present unique approaches to understanding the interplay between identity and youth incarceration, but they do not consider this relationship in the context of a diminished sense of identity. Thus, this paper also aims to evaluate the extent to which incarcerated juveniles experience loss of identity while identifying the potential benefits of musical interventions among this population.

Prisonization

Acclimation to “prison culture” is a key mechanism by which the identity of incarcerated populations progressively deteriorates. This process is better known as prisonization, and it affects those with and without experience in the justice system (Walters, 2003). Prisonization is contingent upon an essential component of incarceration: loss of autonomy (National Research Council et al., 2014). Maintaining order and safety is facilitated through the establishment of strict schedules, robbing incarcerated populations of the opportunity to make choices. It is important to note that this ability to make decisions was done on a regular basis prior to incarceration and often done unconsciously. This shift is a drastic one, and acclimation therefore takes time; however, once acclimated, they are dependent on the established routine (Zamble, 1992). What was formerly an unconscious process of making decisions evolves into an unconscious adherence to pre-established routines and regulations (National Research Council et al., 2014). The customs set out by administration become habits, making re-integration into society significantly more challenging (Irwin, 2005). Although minor, decisions such as when to wake up, eat, go outside, and call family or friends vary between individuals; they make each person unique. Other identifying characteristics include clothes, possessions, hobbies, and leisure pursuits—all of which are strictly regulated (Hardie-Bick, 2018). The loss of autonomy and control in these identifiers becomes a loss of self.

The potential of the prisonization process to “rigidify” within an individual has implications towards psychological well-being and recidivism (Hardie-Bick, 2018; National Research Council et al., 2014). There is a stark difference in the mindset of someone who experiences prisonization, with feelings of isolation and loneliness particularly magnified, enabling an “us against them” mentality (Lerman, 2009). Undoubtedly, strong ties to friends and family reduces recidivism (Hairston, 1991), specifically with female offenders (Barrick et al., 2014; Jiang & Winfree, 2006). However, one caveat to this is the potential negative effects that delinquency-oriented friendships or unhealthy spousal relationships can have on recidivism (Cobbina et al., 2010). With this in mind, the aforementioned argument should be qualified with the clarification that these strong ties should be towards healthy family/friend relationships. Despite these safeguards, prisonization encourages a shift towards antisocial norms (Lerman, 2009), making it difficult to establish or reestablish these important relationships. Additionally, being removed from a predictable and recognizable environment can skew one’s sense of self (Hardie-Bick, 2018). Viewing the social dynamics within correctional facilities as a unique “culture” provides a lens through which prisonization—and its effects on identity—can be viewed.

Difficulties arise when applying these themes to incarcerated juveniles. Questions of whether or not a “prison culture” exists within this population inevitably surface. Confinement is more broadly defined for juveniles than it is for adults. They are often sentenced to a residential facility, which can either be a juvenile detention center, juvenile boot camp, juvenile ranch facility, or group home (Barnert et al., 2016). Juveniles are occasionally tried in the court system as adults. When this occurs, the likelihood of incarceration is higher and sentencing decisions are much less lenient, often resulting in incarceration within an adult prison (Carmichael, 2010; Lambie & Randell, 2013). Research supports the deduction that quality of life is worse for juveniles incarcerated in adult facilities (Fagan & Kupchik, 2011; Lambie & Randell, 2013), yet this is not enough to deem juvenile facilities as being effective in encouraging rehabilitation. Thomas et al. (1983) distributed questionnaires focused on metrics of alienation, prisonization, life motivation, and attitudes towards the legal system to 276 male, juvenile delinquents in a residential facility. Subjects in this study primarily experienced feelings of alienation, prisonization, and opposition to the legal system. Additionally, controlled analyses revealed associations between prisonization and life motivation, illuminating a relationship between identity and life motivation. Limited (and dated) research in this area warrants caution in interpretation of results; however, designation of juvenile delinquency is imparted on all incarcerated youth and can deteriorate a sense of self per the labelling theory (Ascani, 2012; Chassin & Stager, 1984; Kroska et al., 2016; Restivo & Lanier, 2013).

A sociological perspective of identity: identity theory

The concept of identity has been defined by multiple disciplines, yet one’s sense of self is an abstract concept, making it difficult to empirically measure. Burke and Stets (2009) dissected this in their proposed identity theory. This theory outlines three bases of identities: social/group, role, and personal, and verification of these identities enables positive self-esteem outcomes. Social/group identity allows individuals to define themselves through sociocultural or personal groups. Certain personal/societal roles held (student, mother, friend) conform social identity, and unique attributes define one’s personal identity. Stets and Burke (2014) advanced this theory by fragmenting self-esteem into three dimensions, drawing these distinctions from previous sociological and psychological research. Self-esteem is better viewed as a culmination of self-worth, self-efficacy, and authenticity, and identity verification will improve these components of self-esteem, allowing a parallel to be drawn between high self-esteem and a fortified sense of identity. Although seemingly similar, self-worth, self-efficacy, and authenticity are unique and thus associate with identity in different ways. Self-worth is the extent to which people feel positively about themselves, and this arises through verification of social/group identity. Self-efficacy is the perception of one’s ability to impact their environment, and this is attained through verification of role identity (Stets & Burke, 2014). Authenticity encompasses the personal standards that define and individualize people (Erikson, 1995), and this is generated through verification of personal identity (Stets and Burke, 2014). Ultimately, the work of Stets and Burke (2014) views identity through the lens of self-esteem and provides a means by which identity can be measured.

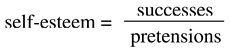

Self-esteem is dynamic. It is continuously changing in response to one’s aspirations and successes. William James (1950) illustrated this concept in the following equation:

According to this model, self-esteem is considered a ratio of one’s successes and ambitions. Cast and Burke (2002) hypothesized that this model could be translated to the idea of identity verification. In both cases, the overarching theme of matching effort to goals is present, connecting self-esteem to identity verification. Self-esteem is thought to be “a direct outcome of successful self-verification” (Cast & Burke, 2002, p. 1046). With identity verification, the “successes” in the above equation would represent self-relevant perception, and “pretensions” would represent an identity standard or goal. Simply put, identity verification occurs when an identity goal is matched by actual performance, or the way one believes others perceive their performance (Cast & Burke, 2002; Stets & Burke, 2014). A match results in individuals feeling satisfied due to their sense of identity being confirmed. Satisfaction is therefore another metric in which identity (specifically its verification) can be measured.

Incarceration and identity

Having a theoretical framework through which identity can be conceptualized allows for a more comprehensive understanding of incarceration and identity, primarily within the perspective of self-esteem. Incarceration and self-esteem have been thoroughly studied, and two opposing bodies of literature have emerged. One body of literature associates crime with low self-esteem (Donnellan et al., 2005; Mier & Ladny, 2017; Oser, 2006), while the other associates crime with high self-esteem (Baumeister & Boden, 1998; Papps & O’Carroll, 1998; Salmivalli, 2001). In a meta-analysis focusing on 42 studies over 25 years, Mier and Ladny (2017) found a negative relationship between self-esteem and crime, though the association was small. The association was found to be larger when looking at delinquency oriented behavior. The variation in literature surrounding this topic alludes to the difficulty in looking at self-esteem as the primary predictor of criminal behavior. Self-esteem may be artificially inflated in some people to avoid the realization that they have low self-esteem (Salmivalli, 2001). Additionally, distinctions are not drawn between high self-esteem, unstable high self-esteem, and narcissism (Mier & Ladny, 2017), making it difficult to establish a causal relationship between high self-esteem and violent behavior. Longitudinal studies veer towards an unstable upbringing and low socioeconomic status as being more robust predictors of delinquent behavior (Bergman & Andershed, 2009; Lahey et al., 1995), yet these factors are not subject to change, making it difficult to derive implications for rehabilitative programming from these findings. Self-esteem, however, is susceptible to fluctuation, and previous research has shown improvements in self-esteem from music-based interventions in incarcerated populations (Cohen, 2012; Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020; Kennedy, 1998).

The trauma of incarceration often invokes an identity crisis (Brison, 1999; Hardie-Bick, 2018). Institutionalization forces individuals into unfamiliar environments and invokes feelings of emptiness and desolation. Consequently, incarcerated populations lose certainty in their sense of self (Maruna & Ramsden, 2004). These sentiments are exacerbated by the premise of the labelling theory. Past actions inform current perceptions, and the criminal/deviant label severely hinders quality of life after imprisonment such that future offending is an inevitability (Hardie-Bick, 2018). In order to begin the process of self-reconstruction, a paradigm shift must occur. Previous mistakes and limitations must be acknowledged, and personal redemption cannot be perceived as something that is out of reach for these populations (Hardie-Bick, 2018; Maruna & Ramsden, 2004). Despite being in an environment where freedoms are stripped, one must retain personal agency and seek positive experiences that facilitate rehabilitation and growth. This already difficult task is considerably more difficult when systemic barriers to recidivist offending adults are considered. Avoiding future criminal behavior is hindered by being placed in a financially disadvantaged position upon release, and the difficulties in gaining employment as a repeat offender rationalize their pessimistic outlook on life trajectory (Maruna & Ramsden, 2004). When asked what it would take to prevent future criminal behavior, recidivist offenders cited “death” and “winning the lottery” (Maruna & Ramsden, 2004, p. 136). For these reasons, encouraging the process of self-reconstruction prior to recurrent cases of recidivism is the best approach, making juvenile justice an ideal setting.

Methods

Participants and setting

All participants in this study were informed that involvement in the project was voluntary and participated out of personal interest. Participants were provided questionnaires and interviewed at the beginning of the study period to assess for self-esteem, life satisfaction, and the effects of incarceration. Following the questionnaire and interview, the participants were enrolled in a music program. The music program’s curriculum was designed around core themes of musical composition, instrument learning, songwriting, and singing as previous literature found success in improving the well-being of delinquent youth with these activities (Chong & Yun, 2020; Hickey, 2018). The program consisted of weekly sessions lasting one hour, and activities were guided in part by active feedback from the program participants. It was assumed that participants had little to no experience with reading and writing music, and elements of the project design reflected that. Instruments purchased included steel drums, electronic pianos, and an electronic drum kit. All melodic instruments were labeled with stickers indicating their respective musical note (C, C#, D, D#, etc.), and songs were often accompanied by a metronome to facilitate uniform timing. In the final weeks of the program, the group worked collaboratively to compose and write lyrics to an original song. This song was performed within the group to provide a positive conclusion to the program. Inclusion of a final performance was also present in Chong and Yun (2020), Cohen (2012), and Mota (2012).

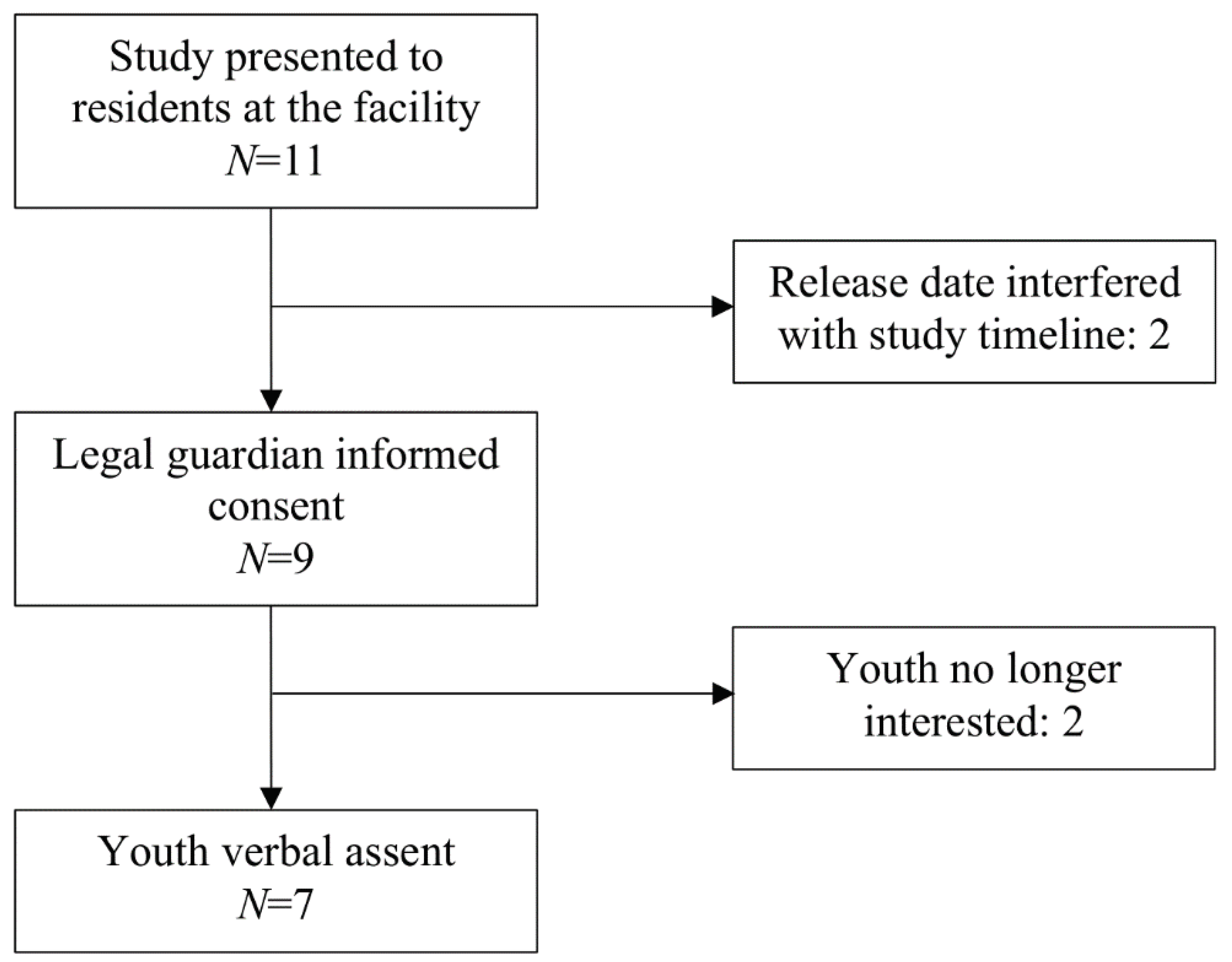

The duration of the music program was eight weeks, and the project took place at a juvenile residential facility for girls in Florida. Residents are those adjudicated to a non-secure placement, and duration of stay is contingent upon assessment of the youth’s risk to reoffend. Operating capacity of the facility is 28 residents, and ages typically range from 12-18. At the time of this study, 20 residents were present at the facility Upon explaining the study, a list of 11 interested participants was compiled. Since all interested participants were under the age of 18, their legal guardians were contacted to obtain informed consent, and verbal assent was obtained from the youth interested in participating. A total of seven participants were included in the study. Given the protected status of the participants as incarcerated youth, specific demographic information was not collected.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Study Participation.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Study Participation.

Data collection and analyses

Data was collected prior to the inception and throughout the music program using a convergent mixed-methods design. Attendance was also taken to assess participant retention. Quantitative data collection involved two Likert style questionnaires focused on metrics of self-esteem and life satisfaction. Qualitative data consisted of a one-on-one interview portion with the participant and researcher. Questions were focused on incarceration, happiness, and self-perception. Participants were provided questionnaires and interviewed before the intervention. Comprehensive field notes were also taken throughout the intervention by the program facilitator to assess group response to the implemented music program. Participants were assigned a random number paired with their quantitative and qualitative responses to protect their identity.

Quantitative data analysis

Self-esteem: Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSS), which consists of a ten-item questionnaire evaluating perceived self-worth using a four-point Likert style response scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Responses to statements include strongly disagree (0), disagree (1), agree (2), and strongly agree (3). Five of the items are reverse scored, meaning a selection of strongly disagree would receive a score of 3 as opposed to 0. Internal reliability for this assessment is strong ( = .84), and it has been used in various contexts

(Bagley et al., 1997; Bagley & Mallick, 2001), including with incarcerated

populations (Chen et al., 2015; Oser, 2006). The scale is additive, with a 0

being the lowest possible score (low self-esteem) and a 30 being the highest

(high self-esteem).

Life satisfaction: Life satisfaction was measured using the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), which consists of a five-item questionnaire evaluating life satisfaction and well-being using a seven-point Likert style response scale (Diener et al., 1985). Responses to statements include strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), slightly disagree (3), neutral (4), slightly agree (5), agree (6), and strongly agree (7). Similar to the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the SWLS has strong internal reliability ( = .87) and has been validated by multiple research studies (Diener et al., 1985; Pavot & Diener, 2008; Samaha & Hawi, 2016). Scoring for this assessment ranges from 5 (extremely dissatisfied) to 35 (extremely satisfied). Unlike the Rosenberg self-esteem scale, certain score ranges are allocated to diagnostic categories. The categories include extremely dissatisfied (5-9), dissatisfied (10-14), slightly dissatisfied (15-19), neutral (20), slightly satisfied (21-25), satisfied (26-30), and extremely satisfied (31-35).

Scores for each question the RSS and SWLS were converted to normalized ratios (numerical score/total possible points per question) to allow for comparison of scores between the two exams. The SWLS questions were designated numerical scores of 0-6 instead of 1-7 to match the scale used in the RSS. Mean score comparisons within and between subjects were conducted using two-tailed T-tests. The degree of variance between data was calculated through two-sample F-tests, and samples that were classified as significantly different were analyzed using the Welch T-test. Otherwise, a Student’s T-test was performed.

Qualitative data analysis

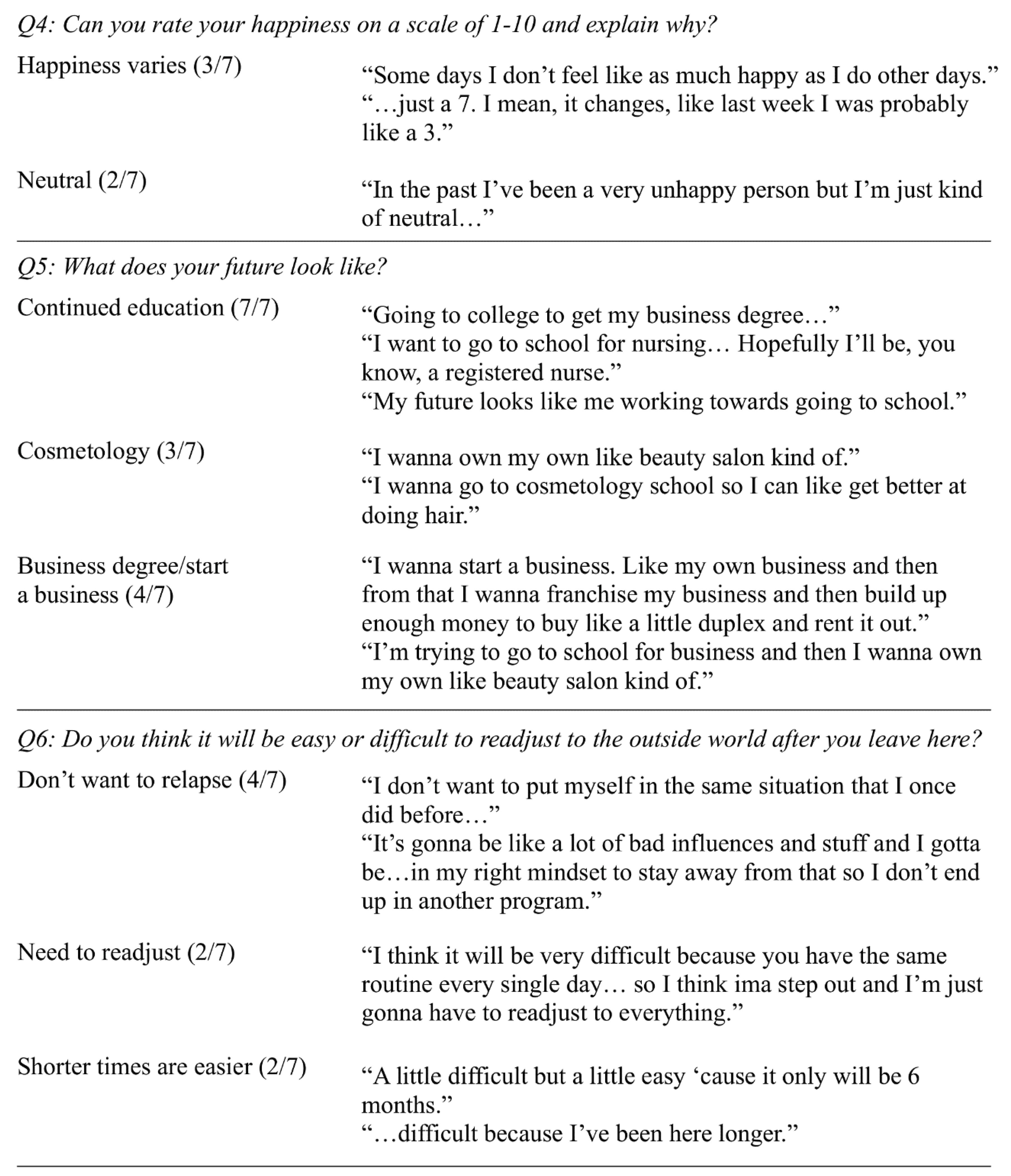

Participants engaged in an interview portion before the intervention. Inspiration for the interview questions came from Cohen (2012), Chong and Yun (2020), and Hardie-Bick (2018). Participants were asked the following: (1) Can you explain what being incarcerated is like and any effects it may have had on you? (2) Have you been to a juvenile detention facility? If so, can you explain what the experience was like and any effects it had on you? (3) How do you perceive yourself? (4) Can you rate your happiness on a scale of 1-10 and explain why? (5) What does your future look like? (6) Do you think it will be easy or difficult to readjust to the outside world after you leave here?

The interview responses of the participants were audio recorded and transcribed. Responses were coded using a thematic content analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Recording of the interviews, informed consent, recruitment, and all other aspects of study design were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida (IRB202101617).

Results

Quantitative data

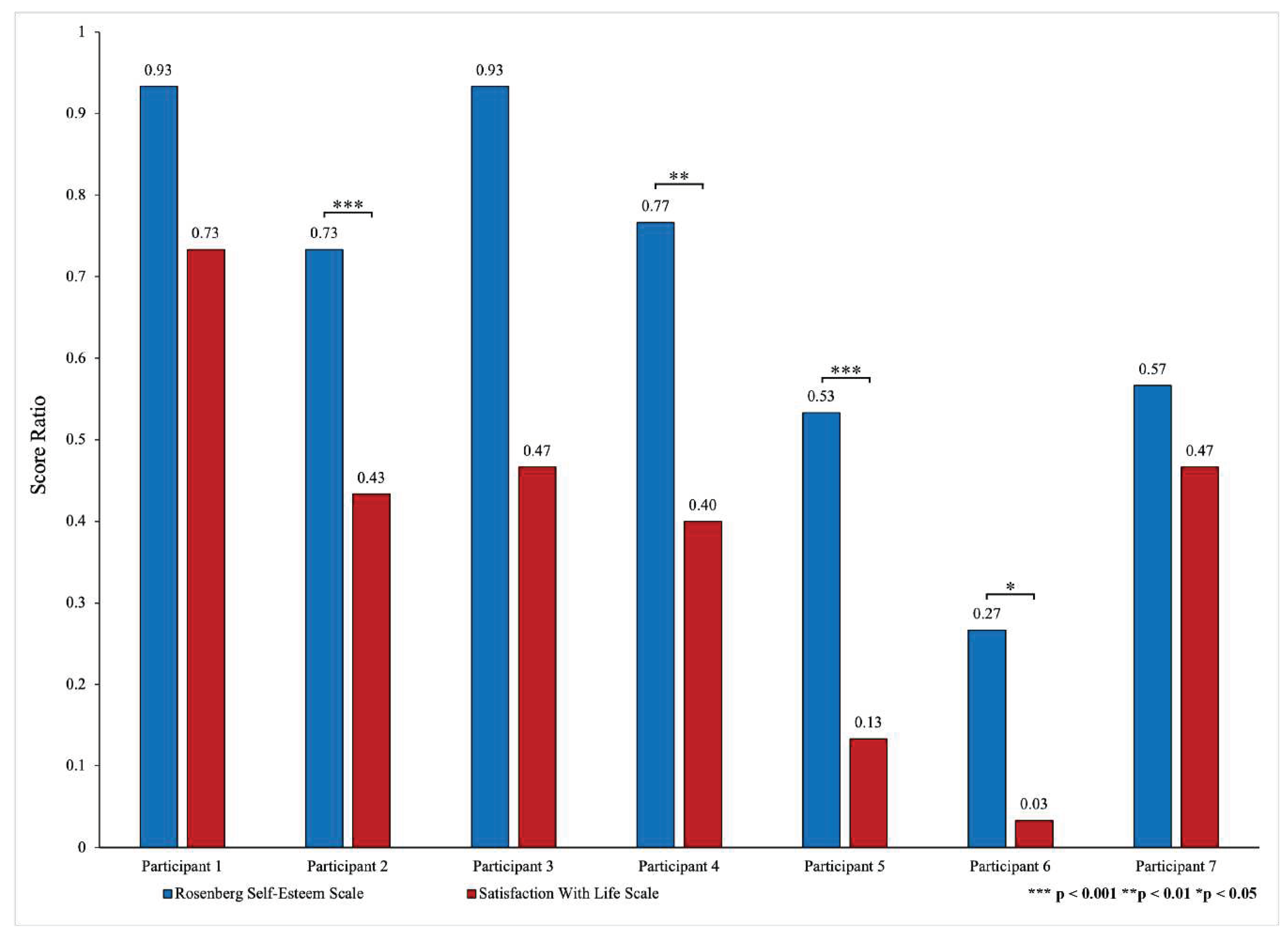

Participants had an average score of 20.29 (N = 7, SD = 7.18) out of a possible 30 on the RSS and 16.43 (N = 7, SD = 6.97) out of a possible 35 on the SWLS. The average score for the SWLS was designated to the “slightly dissatisfied” category. Normalized score ratios were significantly different between averaged RSS and SWLS scored for all participants (p = .037). These differences were predominantly driven by participant 2 (p < .001), participant 5 (p = .002), participant 6 (p < .001), and participant 7 (p = .024).

Figure 2.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and Satisfaction With Life Scale Normalized Score Ratios.

Figure 2.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and Satisfaction With Life Scale Normalized Score Ratios.

Subsequent analyses were conducted on individual questions averaged across all participants. Within the RSS, participants scored lowest on the item “I wish I could have more respect for myself” (.52 score ratio, reverse scored) and highest on the items “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”, “I am able to do things as well as most other people”, “I feel that I'm a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others” (.76 score ratio). Within the SWLS, participants scored lowest on the item “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing” (.26 score ratio) and highest on the item “I am satisfied with my life” (.48 score ratio).

Comparisons in scores between individual items on the RSS and SWLS yielded significant differences. Notably, score ratios on the RSS statements “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”, “I am able to do things as well as most other people”, “I feel that I'm a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others”, and “All in all, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure” (reverse scored) were significantly higher than score ratios on the SWLS statements “In most ways my life is close to ideal”, “The conditions of my life are excellent”, and “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing” (p < .05). Scores were statistically similar between all items on the RSS and SWLS statements “I am satisfied with my life” and “So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life”, as these were the items on the SWLS with the highest score ratios (.48 and .45 respectively).

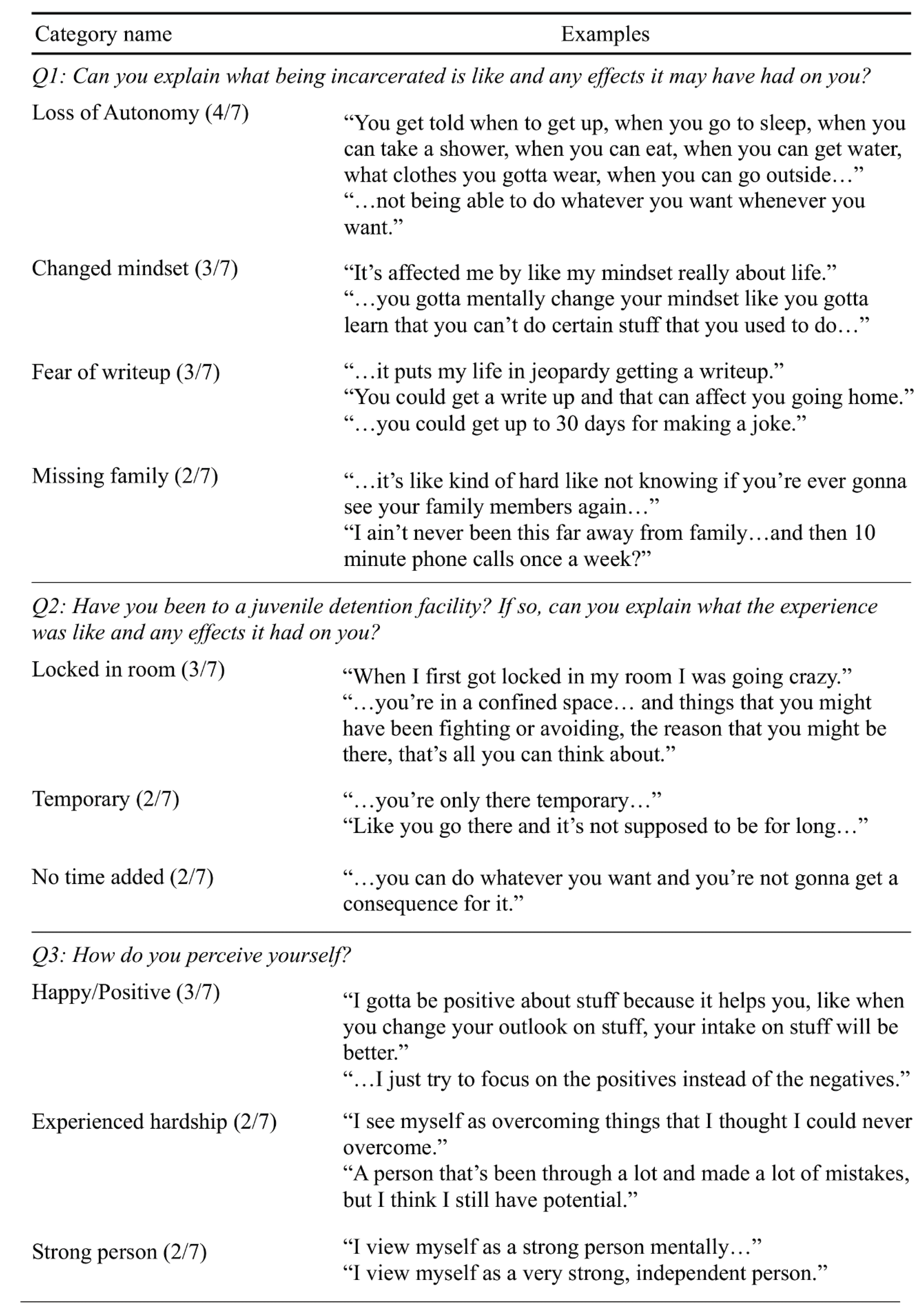

Participant interviews

Responses to each question were individually coded and analyzed across all participants. Overall, there were 18 coded segments for the six interview questions asked. The top four most coded themes were a desire to pursue further education (100%), obtain a business degree/start a business (57%), avoid relapse upon release (57%), and experiencing a loss of autonomy due to incarceration (57%).

A few participants provided particularly insightful responses unable to be captured in the brief quotes from

Table 1. In response to Q1, participant 1 said:

It’s affecting me a lot because I lost, while being in here I lost up to 6 family members. I lost my dad before I got arrested so it’s like kind of hard.

Participant 5 had a response that opposed the sentiments expressed by participant 1:

I don’t think it’s affected me too much ‘cause I have a whole future ahead of me and the rest of my life and I’m young, so yeah.

In response to Q2, participant 6 said:

It was actually better than being here because in juvie, you’re only there temporary, and you know you have the intent of getting out. And there’s no extra time added, you know what I’m saying? Like you do what you do and you leave, but here, it’s worse because this is your life; it becomes your reality.

Participant 3 commented on the experience leading up to incarceration in juvenile detention:

It was a traumatizing experience like when you’ve never been locked up before and like you’re sitting in the courtroom it’s just like “oh I’m getting locked up I’m getting locked up” you’re thinking like “oh I’m going to jail. I’m going to the big house”, but you go to the little house and it’s still the same thing you still get a door slammed in your face…

When asked about self-perception with Q3, participant 1 said:

Sometimes I look at myself as, excuse my language, but a fuck up, like a fuck up in life…

Participant 6 expressed similar negative views:

I just feel like I’m broken…I feel like that’s why I’m here because I didn’t get the help that I needed you know? And I feel like all of us have that individual problem you know? We’re all broken, and we didn’t receive what we needed.

In response to Q4, participants tended to quantify their happiness in the middle of the scale, with an average score of 6.43 (SD = 2.00) and the lowest score being a 4. Participant 1, however, expressed how her optimistic outlook translates to her happiness ranking:

I would say a 10 actually. I’m very like happy and I know it’s like it’s kinda sad because like I’m in here and there’s a lot of people don’t expect you to be happy but at the end of the day you gotta make the best of your situation…

With Q6, participant 5 expressed a time dependency underlying the process of prisonization:

I think it will be easy [to readjust] because I’ve already like been through a program where I have to transition back home but difficult because I’ve been here longer. Like I’m going to end up doing 10 months here and like the rest of the programs I’ve been to are like 30 days or like a month or a couple weeks.

Participant 3 spoke on the authenticity underlying character change within these programs:

I mean some people do change but here like if you feel like you can’t change then you gotta put on a front to go home and you can’t—you’re not gonna go home if you don’t change. And if you don’t change…you get transferred to a higher level and that’s gonna be two to three years you’ve been locked up just because you can’t change who you are.

Observer Field Notes: Music Program

Week one (seven participants)

Participants were provided a name tag sticker and asked to write what they preferred to be called, allowing for control over their sense of identity. Three participants chose to be identified by nicknames. Participants had a preference towards the electronic pianos, but those who played the steel drums grew to like them, eventually calling themselves “the stoners.” The first session predominantly consisted of playing the G scale (G, A, B, C, D, E, F#, G) and a few chords, with participants appearing to have a positive response to the cohesive sound. Participants were grateful for the organization of the event; all of them expressed thanks upon conclusion and one offered a hug.

Week two (seven participants)

The session (and future sessions) began with participants playing the G scale to warm up. A different staff member sat in on this session and was stricter with the participants. They were treated more like children/delinquents, and their comments were often censored by the staff member. Their sense of self-expression appeared to be diminished in comparison to week one, demonstrated through an overall less excited demeanor during the session. Attempts to build on what was taught in the previous class by having participants play chord progressions were met with a lack of satisfaction from participants as the process became overcomplicated. They could not create a harmonious sounding product by the end of the session and were less likely to take pride in what they did accomplish.

Week three (four participants)

Attendance was lowest this week due to participants being provided the option to either sit in on the music program or take a shower while there was still hot water. From the perspective of a facilitator, the smaller number of participants was easier to manage and allowed for a greater sense of closeness and community. The music production software, garageband, was introduced during this session, and participants played background chords and provided percussive claps to create the song. Participants were engaged and appeared to enjoy watching the production process. Desiring to see a finished product, they asked to look through previous, personal projects. Despite being a music program, much of the conversation was not related to the music that was being created (e.g., discussions over the best city in Florida). One participant remarked that they were happy to have this music program and that it made their day a lot better, and another asked if they could have their personal music produced.

Week four (seven participants)

The garageband song created the previous week was played for the participants, and they were asked to write lyrics that would be performed for the group at the end of the session. Some participants initially expressed that they did not want to write verses, but everyone eventually wrote their own verse. Participants separated off into groups and wrote verses that coincided with their friends within the smaller group. A few participants were initially nervous to perform their verse for the group, but they overcame these nerves and worked collaboratively to sequentially perform everyone’s verse, creating a cohesive song. The following weeks of the program consisted of songwriting activities since participants appeared to have the most positive response and engagement to the songwriting.

Week five (seven participants)

This session was informal and less cohesive as participants came in with pre-written songs they wanted to perform over instrumental tracks to popular songs. Overall, participants were uninterested in the instruments, and some chose not to perform the warmup G scale in the beginning of the session. Almost every individual entered with a desire to perform a certain song (whether it be an individual performance or duet with another participant). Participants separated into groups to rehearse their songs until they were able to perform along to their desired instrumental track within their group. Participants appeared to enjoy this session more than the earlier sessions, and most expressed feeling better after the session.

Weeks six and seven (six participants, seven participants)

Within these weeks, the participants were presented with an overarching theme of “change” for the final collaborative original song that would be performed for the group on the final week. Using a beat that was previously created, each participant was asked to write a verse about the role change played in their lives. Participants again separated into their small groups and worked within them to write their verses and get their peers’ approval. The staff member sitting in on the session came up with a simple hook for the song: “Change will come in due time,” and she (along with two participants) sang this hook between the verses written by the participants, allowing for collaboration not only between participants, but between participants and staff as well. Participants began to learn each other’s verses and sing along to multiple parts of the song.

Week eight (seven participants)

Participants engaged in a final performance of their collaborative original song with a few staff members sitting in. Participants were then asked in an informal, unprompted manner to provide any feedback on the program. Many generally expressed that it improved their mood for that day, and that they looked forward to the sessions. One participant expressed appreciation of how the music program allowed for her to express herself. Another participant shared that she was looking for a private place to cry one week, and a staff member had approached her to share that the music program was starting shortly. Due to this, she no longer felt the need to cry and was excited to participate in the music program. A few participants expressed that the sessions provided a distraction from the feeling of incarceration.

Discussion

The results of this study provide insight into the relationship between juvenile incarceration and identity. When considering self-esteem as a proxy measure for one’s sense of identity, comparisons can be made between scores from this population and incarcerated women. In a study of 56 incarcerated women in the US with an average sentence length of 113.30 months, their average RSS score was 9.29 (Oser, 2006). The tested juvenile sample had an average score that was 118% higher (20.29) alluding to clear differences between the tested adult and juvenile samples. Interestingly, scores on the RSS within this tested juvenile sample were more similar to non-incarcerated, age matched counterparts (Bagley et al., 1997; Bagley & Mallick, 2001). Qualitative data from Q6 suggests that this research sample did not report strong feelings of prisonization. Despite previous research findings indicating juveniles can be susceptible to prisonization (Thomas et al., 1983), 57% of participants stated that their primary concern in being released was increased exposure to temptations while only 29% of participants mentioned difficulties in readjusting to the outside world, a key indicator of prisonization. Additionally, qualitative data in Q3 suggest that this sample was not particularly prone to the tenets of the labelling theory. A few participants held negative self-perceptions, but none perceived themselves as a “delinquent” or “criminal.” The delinquent label imposed on them throughout the incarceration process did not translate into their sense of self, which contrasts the experience of other incarcerated youth (Chassin & Stager, 1984; Kroska et al., 2016). This sample did not experience deterioration of identity through the common mechanisms seen in incarcerated populations, and it would therefore be reductive to extrapolate previous research of rehabilitative programming goals with incarcerated populations (Cohen, 2012; Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020; Mota, 2012) to this sample of youth. Stets and Burke (2014) suggest a close relationship between identity verification and self-esteem. Verification of one’s identities encourages improvements in self-esteem. Within this framework, it can be inferred that one who is established and confident in their sense of self should have self-esteem scores that reflect this. On average, this population has as much confidence in their worth and abilities as similarly aged individuals who are not incarcerated (Bagley et al., 1997; Bagley & Mallick, 2001). Thus, rehabilitative interventions aimed to improve self-esteem may not be as efficacious as they would be in individuals with problematically low self-esteem.

Satisfaction with life follows a different trend than what is seen with self-esteem. When translated to normalized ratios, participants in this sample presented with a score on the SWLS that was significantly lower than the RSS (p = .037), indicating a satisfaction with life that is comparatively worse than self-esteem. Qualitative data from Q1 and Q5 suggest negative affect towards incarceration and positive views towards their potential futures respectively, views that are generally not seen in incarcerated adults (Hardie-Bick, 2018; Maruna & Ramsden, 2004). Given the pairing of this optimistic outlook with their current situation, the overall decreased life satisfaction is reasonable. The lowest scoring question of “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing” can also be justified within this perspective. When comparing mean SWLS scores to the nearest representative population with normative data (300 US undergraduate females), US undergraduate females have an average SWLS score of 25.65 (Pavot & Diener, 2008), which is 56% higher than this incarcerated juvenile sample. In rationalizing these clear differences, it is worth noting that the connection between satisfaction and one’s sense of identity is indirect. As mentioned previously, high self-esteem is a product of successful self-verification, and successful self-verification entails the matching of one’s identity goal with how they believe others perceive their performance (Cast & Burke, 2002; Stets & Burke, 2014). This match results in individuals feeling a sense of satisfaction (Cast & Burke, 2002), but this satisfaction may be limited to self-satisfaction, which has greater associations with self-worth and authenticity than it does overall life satisfaction. Therefore, it would not be unreasonable to assume that individuals with a strong sense of identity do not necessarily have life satisfaction. Future research should consider exploring measures of self-worth and authenticity as more accurate operational definitions of identity; however, the SWLS data exemplifies a way in which the tested juvenile sample differs from non-incarcerated counterparts.

Implementation of a music program appeared to elicit a positive response from the participants. Tailoring the program to active feedback during the process allowed for insight into the participant’s preferences as well as potential directions for future programming within similar populations. Participants were generally less engaged in the earlier weeks that included activities of instrumental performance and learning. The activity this group appeared to enjoy most was writing verses over instrumental tracks of popular songs, as it was more within their realm of experience than learning to play songs on the provided instruments. This has positive implications for future programming as a music program focused on this enjoyable activity is of no cost to facilities as it only requires a device to play the instrumental tracks. Due to participants’ positive response to the customized activities, residents who were not in the program approached facility staff asking to join the program, indicating that the positive response to the music program inspired a desire to participate despite initial disinterest. The unprompted feedback session signified that general quality of life within the facility improved for participants in the program, a finding that is by no means exclusive to this particular group (Chen et al., 2015; Chong & Yun, 2020; Cohen, 2012; Hickey, 2018; Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020; Kennedy, 1998; Mota, 2012). Feedback also indicated that some participants were able to experience release from the feelings of incarceration, a finding analogous to the qualitative feedback from incarcerated adults (Kyprianides & Easterbrook, 2020; Mota, 2012). The program provided a creative outlet that allowed participants to engage in a form of self-expression previously unavailable to them, and it provided a sense of departure from life as an incarcerated juvenile. The music program was able to provide respite, but no participant indicated any long-term changes from participation in the program within the informal, unprompted feedback period.

Although positive changes in well-being due to the program were observed and significant differences were found between self-esteem and life satisfaction, this study presents limitations. Namely, the sample size was small, so the collected data should be interpreted with caution. This study also sought to utilize validated questionnaires that could serve as a proxy measure for identity. Results indicated that life-satisfaction may be less representative than self-satisfaction measures such as self-worth or authenticity. Therefore, conclusions made about the lack of identity deterioration within these participants could have been strengthened with validated questionnaires of greater relevance. Variations in human behavior present another limitation to this study. The experience of incarceration differs between individuals and across countries. In a study of 200 male Chinese prisoners, results showed that self-esteem (as measured through the RSS) improved upon implementation of a music program, yet the baseline self-esteem score was 25.92 (Chen et al., 2015), a score 179% higher than the incarcerated women tested in Oser (2006) and 28% higher than the tested juveniles within this study. These differences speak to a necessity in assessing each incarcerated research sample independently of one another, a finding supported by the work of Wolf and Holochwost (2016). The emphasis their analyses placed on the role individuals engaging with their environment play in the interpersonal dynamics of each setting is particularly relevant to this field of research. Additionally, conclusions of improvements in either self-esteem or life satisfaction due to the implemented music program cannot be made, yet the feedback portion of the final session did not support any indication that either of these measures would significantly increase. Improvements experienced by participants were expressed in the context of transient relief from their current stressor of incarceration. Mier and Ladny (2017) found a small negative association between self-esteem and crime; however, the relationship between crime, low socioeconomic status, and unstable upbringing is much stronger and supported by longitudinal analyses (Bergman & Andershed, 2009; Lahey et al., 1995). Consequently, improvements in self-esteem are less likely to reduce recidivist offending than the more salient aforementioned factors. It is for this reason that effective, long-term rehabilitative programming is difficult to conceptualize. Previous literature on rehabilitative music programs with incarcerated populations also does not include follow-up data collection after program termination, exacerbating these difficulties. Thus, it should be assumed that the improvements in well-being observed within this study are likely temporary. In light of these limitations, this study provides valuable insight into the experience of juvenile incarceration; the relationship (or lack thereof) between crime, self-esteem, juvenile incarceration, and identity; and the potential benefits of music-based rehabilitative programming in improving well-being while incarcerated.

References

- Abrams, L. S., & Hyun, A. (2009). Mapping a Process of Negotiated Identity Among Incarcerated Male Juvenile Offenders. Youth & Society, 41(1), 26–52. [CrossRef]

- Ascani, N. (2012). Labeling theory and the effects of sanctioning on delinquent peer association: A new approach to sentencing juveniles. Perspectives, 4. https://scholars.unh.edu/perspectives/vol4/iss1/10.

- Bagley, C., Bolitho, F., & Bertrand, L. (1997). Norms and Construct Validity of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in Canadian High School Populations: Implications for Counselling. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 31(1), 82-92. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ553572.pdf.

- Bagley, C., & Mallick, K. (2001). Normative Data and Mental Health Construct Validity for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in British Adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 9(2–3), 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Barnert, E. S., Perry, R., & Morris, R. E. (2016). Juvenile incarceration and health. Academic Pediatrics, 16(2), 99–109. [CrossRef]

- Barrick, K., Lattimore, P. K., & Visher, C. A. (2014). Reentering women: The impact of social ties on long-term recidivism. The Prison Journal, 94(3), 279–304. [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Boden, J. M. (1998). Aggression and the self: High self-esteem, low self-control, and ego threat. Human Aggression, 111–137. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, L. R., & Andershed, A. K. (2009). Predictors and outcomes of persistent or age-limited registered criminal behavior: A 30-year longitudinal study of a Swedish urban population. Aggressive Behavior, 35(2), 164–178. [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Brison, S. J. (1999). Trauma narrative and the remaking of the self. In M. Bal, J. Crewe, & L. Spitzer (Eds.), Acts of memory: Cultural recall in the present (pp. 39–54). Hanover, CT: University Press of New England.

- Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Catterall, J. S., Dumais, S. A., & Hampden-Thompson, G. (2012). The arts and achievement in at-risk youth: Findings from four longitudinal studies. Washington, DC: National Endowment for the Arts.

- Carmichael, J. T. (2010). Sentencing disparities for juvenile offenders sentenced to adult prisons: An individual and contextual analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(4), 747–757. [CrossRef]

- Cast, A. D., & Burke, P. J. (2002). A theory of self-esteem. Social Forces, 80(3), 1041–1068. [CrossRef]

- Chassin, L., & Stager, S. F. (1984). Determinants of self-esteem among incarcerated delinquents. Social Psychology Quarterly, 47(4), 382–390. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. J., Hannibal, N., & Gold, C. (2015). Randomized trial of group music therapy with chinese prisoners. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(9), 1064–1081. [CrossRef]

- Chong, H. J., & Yun, J. (2020). Music therapy for delinquency involved juveniles through tripartite collaboration: A mixed method study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Cobbina, J. E., Huebner, B. M., & Berg, M. T. (2010). Men, women, and postrelease offending: An examination of the nature of the link between relational ties and recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 58(3), 331–361. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M. L. (2012). Harmony within the walls: Perceptions of worthiness and competence in a community prison choir. International Journal of Music Education, 30(1), 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M. L. (2019). Choral singing in prisons: Evidence-Based activities to support returning citizens. The Prison Journal, 99(4), 106S-117S. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2005). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16(4), 328–335. [CrossRef]

- Fagan, J., & Kupchik, A. (2011). Juvenile incarceration and the pains of imprisonment. Duke Forum for Law & Social Change, 3, 29–61. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dflsc/vol3/iss1/3.

- Hairston, C. F. (1991). Family ties during imprisonment: Important to whom and for what? The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 18(1), 87–104.

- Hardie-Bick, J. (2018). Identity, imprisonment, and narrative configuration. New Criminal Law Review, 21(4), 567–591. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, M. (2018). “We all come together to learn about music”: A qualitative analysis of a 5-Year music program in a juvenile detention facility. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(13), 4046–4066. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J. (2005). The warehouse prison: Disposal of the new dangerous class. Roxbury Publishing.

- James, W. (1950). The principles of psychology (Revised ed.). Dover Publications.

- Kennedy, R. (1998). The effects of musical performance, rational emotive therapy and vicarious experience on the self-efficacy and self-esteem of juvenile delinquents and disadvantaged children [unpublished manuscript]. University of Kansas.

- Kroska, A., Lee, J. D., & Carr, N. T. (2016). Juvenile delinquency and Self-Sentiments: Exploring a labeling theory proposition*. Social Science Quarterly, 98(1), 73–88. [CrossRef]

- Kyprianides, A., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2020). “Finding rhythms made me find my rhythm in prison”: The role of a music program in promoting social engagement and psychological well-being among inmates. The Prison Journal, 100(4), 531–554. [CrossRef]

- Lahey, B. B., Loeber, R., Hart, E. L., Frick, P. J., Applegate, B., Zhang, Q., Green, S. M., & Russo, M. F. (1995). Four-year longitudinal study of conduct disorder in boys: Patterns and predictors of persistence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(1), 83–93. [CrossRef]

- Lambie, I., & Randell, I. (2013). The impact of incarceration on juvenile offenders. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(3), 448–459. [CrossRef]

- Lerman, A. E. (2009). The people prisons make: Effects of incarceration on criminal psychology. In S. Raphael & M. A. Stoll (Eds.), Do Prisons Make Us Safer?: The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom (Illustrated ed., pp. 151–176). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Maruna, S., & Ramsden, D. (2004). Living to tell the tale: Redemption narratives, shame management, and offender Rehabilitation. Healing Plots: The Narrative Basis of Psychotherapy., 129–149. [CrossRef]

- Mier, C., & Ladny, R. T. (2017). Does self-esteem negatively impact crime and delinquency? A meta-analytic review of 25 years of evidence. Deviant Behavior, 39(8), 1006–1022. [CrossRef]

- Mota, G. (2012). A music workshop in a women’s prison: crossing memories, attributing meanings. In Proceedings of the 24th International Seminar on Research in Music Education of the ISME Research Commission, (pp. 167-174). Thessaloniki, Greece: International Society for Music Education.

- National Research Council. (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences (S. Redburn, B. Western, J. Travis, & Committee on Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration, Eds.; Illustrated ed.). National Academies Press.

- Oser, C. B. (2006). The criminal offending–self-esteem nexus. The Prison Journal, 86(3), 344–363. [CrossRef]

- Papps, B., & O’Carroll, R. E. (1998). Extremes of self-esteem and narcissism and the experience and expression of anger and aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 24(6), 421–438. [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152. [CrossRef]

- Peacock, R. (2006). Identity development of the incarcerated adolescent : A comparitive analysis [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pretoria]. http://hdl.handle.net/2263/58971.

- Restivo, E., & Lanier, M. M. (2013). Measuring the contextual effects and mitigating factors of labeling theory. Justice Quarterly, 32(1), 116–141. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image (Vol. 1979) [E-book]. Princeton University Press. [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C. (2001). Feeling good about oneself, being bad to others? Remarks on self-esteem, hostility, and aggressive behavior. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(4), 375–393. [CrossRef]

- Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 321–325. [CrossRef]

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2014). Self-Esteem and identities. Sociological Perspectives, 57(4), 409–433. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. W., Hyman, J., & Winfree, L. T. (1983). The impact of confinement on juveniles. Youth & Society, 14(3), 301–319. [CrossRef]

- Walters, G. D. (2003). Changes in criminal thinking and identity in novice and experienced inmates. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30(4), 399–421. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D. P., & Holochwost, S. J. (2016). Music and juvenile justice: A dynamic systems perspective. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. [CrossRef]

- Zamble, E. (1992). Behavior and adaptation in long-term prison inmates. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 19(4), 409–425. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).