Submitted:

21 August 2023

Posted:

22 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

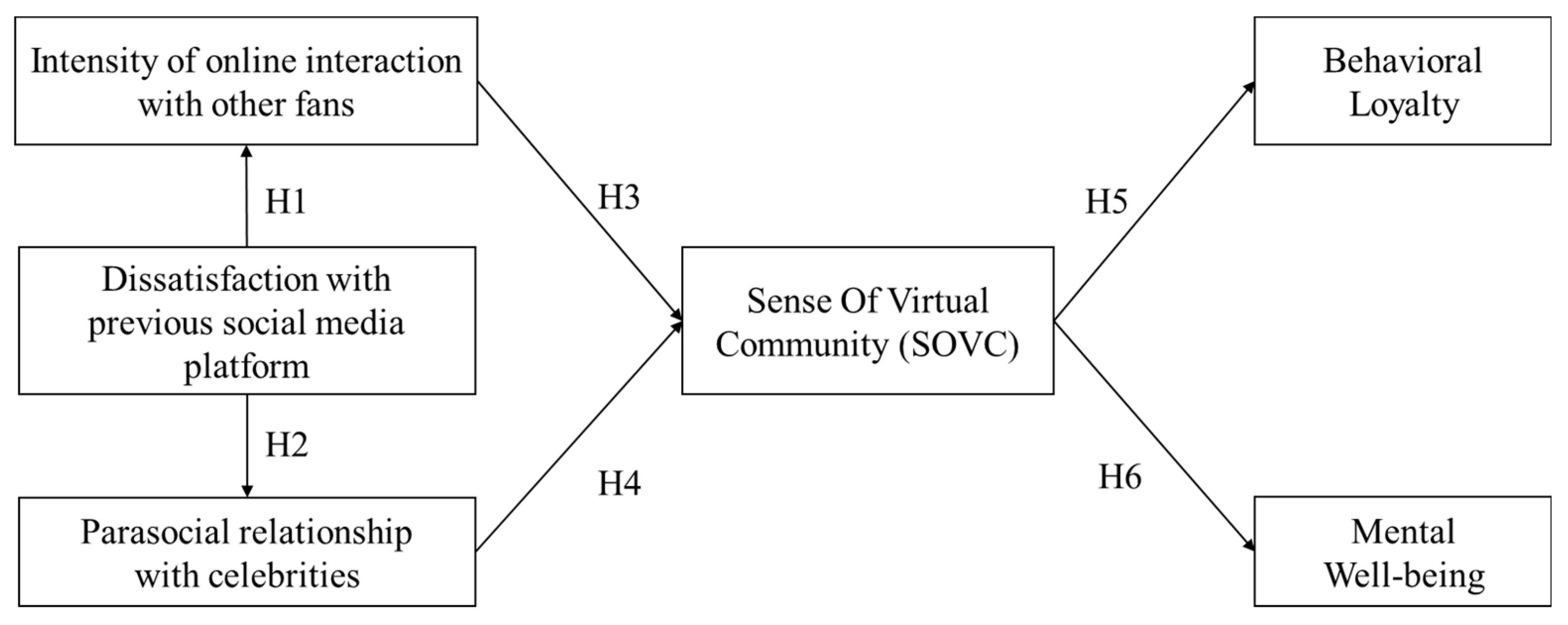

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Fan Community Platform

2.1.1. Intensity of Online Interaction with Other Fans

2.1.2. The Parasocial Relationship with Celebrities

2.2. Dissatisfaction with Previous Social Media and Fan Activities on the Fan Community Platform

2.3. Sense of Virtual Community (SOVC) and Fan Activities on the Fan Community Platform

2.4. SOVC and Behavioral Loyalty

2.5. SOVC and Mental Well-Being

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Omoush, K.S.; Orero-Blat, M.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. The role of sense of community in harnessing the wisdom of crowds and creating collaborative knowledge during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 765–774. [CrossRef]

- Gauxachs, A.S.; Aiguabella, J.M.A; Bosch, M.D. Coronavirus-driven digitalization of in-person communities: Analysis of the catholic church online response in Spain during the pandemic. Religions, 2021, 12, 311. [CrossRef]

- Pancani, L.; Marinucci, M.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1,006 Italians under COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663799. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. COVID-19 and the need for action on mental health. 2021. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Gabbiadini, A.; Baldissarri, C.; Durante, F.; Valtorta, R.R.; De Rosa, M.; Gallucci, M. Together apart: the mitigating role of digital communication technologies on negative affect during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 554678. [CrossRef]

- Marinucci, M.; Pancani, L.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Online social connections as surrogates of face-to-face interactions: A longitudinal study under Covid-19 isolation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107102. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G.; Powell, J.; Englesakis, M.; Rizo, C.; Stern, A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. Bmj 2004, 328, 1166. [CrossRef]

- Masciantonio, A.; Bourguignon, D.; Bouchat, P.; Balty, M.; Rimé, B. Don’t put all social network sites in one basket: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, and their relations with well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS one 2021, 16, e0248384. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.P.; Chang, C.W. Does the social platform established by MMORPGs build social and psychological capital? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 129, 107139. [CrossRef]

- Kanozia, R.; Ganghariya, G. More than K-pop fans: BTS fandom and activism amid COVID-19 outbreak. Media Asia 2021, 48, 338–345. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, H. M. The effect of online fan community attributes on the loyalty and cooperation of fan community members: The moderating role of connect hours. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 232–243. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.M.; & Kim, M. The impact of a sense of virtual community on online community: Does online privacy concern matter? Internet Res. 2021, 31, 519–539. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Liao, Y.C. Exploring the linkages between perceived information accessibility and microblog stickiness: The moderating role of a sense of community. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 833–844. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Shim, K. Antecedents of microblogging users’ purchase intention toward celebrities’ merchandise: Perspectives of virtual community and fan economy. J. Psychol. Res. 2021, 2, 11–26. [CrossRef]

- Obst, P.; Stafurik, J. Online we are all able bodied: Online psychological sense of community and social support found through membership of disability-specific websites promotes well-being for people living with a physical disability. J. Community. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 20, 525–531. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, I.P.; Lin, C.C.; Wang, K.S. Sense of virtual community: Antecedents and consequences. J. Electron. Bus. 2010, 13, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, T.; Wu, X. More is better? The influencing of user involvement on user loyalty in online travel community. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 357–369.

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Intentional social action in virtual communities. J. Interact. Mark. 2002, 16, 2–21. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Mahajan, V. The economic leverage of the virtual community. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 5, 103–138. [CrossRef]

- Hagel, I.I.I.; Armstrong, A.G. Net gain. McKinsey Q. 1997, 1, 140–153.

- Obst, P.; Zinkiewicz, L.; Smith, S.G. Sense of community in science fiction fandom, Part 1: Understanding sense of community in an international community of interest. J. Community Psychol. 2002, 30, 87–103. [CrossRef]

- Annett, S. Anime fan communities: Transcultural flows and frictions. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, United States, 2014.

- Bennett, L. ‘If we stick together, we can do anything’: Lady Gaga fandom, philanthropy and activism through social media. Celebr. Stud. 2014, 5, 138–152. [CrossRef]

- Scardaville, M.C. Accidental activists: Fan activism in the soap opera community. Am. Behav. Sci. 2005, 48, 881–901.

- McLaren, C.; Jin, D.Y. “You can’t help but love them”: BTS, transcultural fandom, and affective identities. Korea J. 2020, 60, 100–127. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.D., Choi, M.G. Research on the influence of interaction, identification and recommendation of entertainment communication platform. J. Korea Entmt. Ind. Assoc. 2021, 15, 23–33. [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, K.; Jaakkola, E.; Neganova, I. Drivers, types and value outcomes of customer-to-customer interaction: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2018, 28, 710–732, 10.1108/JSTP-01-2017-0010.

- Ringland, K.E.; Wolf, C.T. “You're my best friend.” finding community online in BTS’s fandom, ARMY. XRDS 2022, 28, 66–69.

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R.R. Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Goldhoorn, C. Horton and Wohl revisited: Exploring viewers’ experience of parasocial interaction. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 1104–1121. [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I. Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 134–148. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Defining identification: A theoretical look at the identification of audiences with media characters. Mass Commun. Soc. 2001, 4, 245–264. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M.; Perse, E.M. Audience activity and soap opera involvement a uses and effects investigation. Hum. Commun. Res. 1987, 14, 246–268. [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering parasocial relationships with celebrities on social media: Implications for celebrity endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [CrossRef]

- Tukachinsky, R.H. Para-romantic love and para-friendships: Development and assessment of a multiple-parasocial relationships scale. Am. J. Media Psychol. 2011, 3, 73–94.

- Stern, B.B.; Russell, C.A.; Russell, D.W. Hidden persuasions in soap operas: Damaged heroines and negative consumer effects. Int. J. Advert. 2007, 26, 9–36.

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L. Delivering quality service: Balancing customer perceptions and expectations. The Free Press: New York, United States, 1990.

- Bolfing, C.P. How do customers express dissatisfaction and what can service marketers do about it?. J. Serv. Mark. 1989, 3, 5–23. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, R.Z. Why do people switch mobile payment service platforms? An empirical study in Taiwan. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101312. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Abad, N.; Hinsch, C. A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives use, and connection rewards it. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2011, 1, 2–15. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.C.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Lim, J. Retaining and attracting users in social networking services: An empirical investigation of cyber migration. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 239–253. [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.L. Developing a sense of virtual community measure. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 827–830. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.L.; Markus, M.L. The experienced “sense” of a virtual community: Characteristics and processes. Data Base Adv. Inf. Syst. 2004, 35, 64–79. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Olfman, L.; Ko, I.; Koh, J.; Kim, K. The influence of on-line brand community characteristics on community commitment and brand loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2008, 12, 57–80. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Zhang, D. The effects of sense of presence, sense of belonging, and cognitive absorption on satisfaction and user loyalty toward an immersive 3D virtual world. Lect. Notes Bus. Inf. Process. 2011, 52, 30–43. [CrossRef]

- Riedl, C.; Köbler, F.; Goswami, S.; Krcmar, H. Tweeting to feel connected: A model for social connectedness in online social networks. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Int. 2013, 29, 670–687.

- McMillan, D. W. Sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 315–325. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, S.; Kim, J. Factors influencing K-pop artists’ success on V live online video platform. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102090. [CrossRef]

- Kassing, J.W.; Sanderson, J. Fan–athlete interaction and Twitter tweeting through the Giro: A case study. Int. J. Sport Commun, 2010, 3, 113–128. [CrossRef]

- Jarzyna, C.L. Parasocial interaction, the COVID-19 quarantine, and digital age media. Hu. Arenas, 2021, 4, 413–429. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Brand loyalty: A conceptual definition. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 1971.

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.O.; Sasser, W.E. Why satisfied customers defect. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 88–99.

- Ko, E.; Megehee, C.M. Fashion marketing of luxury brands: Recent research issues and contributions. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1395–1398. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Chestnut, R.W.; Fisher, W.A. A behavioral process approach to information acquisition in nondurable purchasing. J. Mark. Res. 1978, 15, 532–544. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, P.J.; Gray, P.H.; Butler, B.S. Research note—the impact of community commitment on participation in online communities. Inform. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 841–854. [CrossRef]

- Kloos, B.; Hill, J.; Wandersman, T.E.; Elias, A.; Dalton, J. (2012). Introducing community psychology. In Community Psychology: Linking individuals and communities. Wadsworth: CA, United States, 2012; pp. 2-69.

- Prilleltensky, I. Wellness as Fairness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 49, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081.

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–222. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social Well-Being. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1998, 61, 121–140. [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Pirini, C.; Keyes, C.; Joshanloo, M.; Rostami, R.; Nosratabadi, M. Social participation, sense of community and social well being: A Study on American, Italian and Iranian university students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 97–112. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. (2003). Complete mental health: An agenda for the 21st century. In Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived.; Keyes C.L.M, Haidt, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, United States, 2003, pp. 293–312.

- Albanesi, C., Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. Sense of community, civic engagement and social well-being in Italian adolescents. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 17, 387–406. [CrossRef]

- Coulombe, S.; Krzesni, D.A. Associations between sense of community and wellbeing: A comprehensive variable and person-centered exploration. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 1246–1268. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, W.B.; Cotter, P.R. The relationship between sense of community and subjective well-being: A first look. J. Community Psychol. 1991, 19, 246–253. [CrossRef]

- Kushlev, K.; Leitao, M.R. The effects of smartphones on well-being: Theoretical integration and research agenda. Curr. Opin. Psychol., 2020, 36, 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Gray, K. Does online technology make us more or less sociable? A preliminary review and call for research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 473–491. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Money, A.H.; Samouel, P.; Page, M. Research methods for business. Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 336–337. [CrossRef]

- Howe, T.R.; Aberson, C.L.; Friedman, H.S.; Murphy, S.E.; Alcazar, E.; Vazquez, E.J.; Becker, R. Three decades later: the life experiences and mid-life functioning of 1980s heavy metal groupies, musicians, and fans. Self Identity 2015, 14, 602–626. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Santero, N.K.; Kaneshiro, B.; Lee, J.H. Armed in ARMY: A case study of how BTS fans successfully collaborated to# MatchAMillion for Black Lives Matter. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2021.

- MacKerron, G.J.; Egerton, C.; Gaskell, C.; Parpia, A.; Mourato, S. Willingness to pay for carbon offset certification and co-benefits among (high-) flying young adults in the UK. Energy policy 2009, 37, 1372–1381. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Ko, Y.K.; Shin, H.C.; Cho, Y.R. (2012). Psychometric Evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in South Koreans. Korean J. Psychol. 2012, 31, 369–386.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50.

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152.

- Wong, K.K.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32.

- Haenlein, M.; Kaplan, A.M. (2004). A beginner’s guide to partial least squares analysis. Understanding Stat. 2004, 3, 283–297. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94.

- Stewart, K.; Townley, G. How far have we come? An integrative review of the current literature on sense of community and well-being. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 66, 166–189. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Nguyen, A.T. How music fans shape commercial music services: A case study of BTS and ARMY. In Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR), 2020.

| Fandom | Army | Blinks | NCTzen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genre | K-pop | K-pop | K-pop |

| Artist | BTS | Black Pink | NCT |

| Year Established | 2013 | 2016 | 2017 |

| Management Agency | HYBE | YG | SM |

| Social Media | Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, Weverse | Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, Weverse | Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, LYSN |

| Official fan community | Weverse | Weverse | LYSN/Bubble |

| Merchandise shop | Weverse shop | Weverse shop | SM Town & Store |

| Members | 14.6 million (Wever) | 2.8 million (Wever) | Unknown |

| Fandom | Army | Blinks | NCTzen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company | HYBE | Dear U (SM) | NC Soft |

| Company Type | Entertainment company | Entertainment company | Video game developer |

| MAU1 | 6.8 million | Differ by each app | 4.4 million |

| Number of Artists | 43 | 249 | 32 |

| Features | Official e-commerce (Weverse shop), Acquisition of V Live2) | Direct celebrity to fan message | Original content (Universe Original), Digital currency (Clap) |

| Communication with artists | Artists’ posts, Comments on artists’ posts | ||

| _ Free users | Story function | Change artist profile | Change artist profile, Separate posts by member |

| _ Subscribed users | Exclusive member content, merchandise, early-bird tickets | Video fan sign Artists’ handwritten letter |

Artists’ private message (one-to-many), AI voice message |

| Communication with other fans | Fans’ posts | ||

| Subscribe to other fans’ accounts | Open chat | Subscribe to other fans’ accounts |

| Measures | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 28 | 13.9 |

| Female | 174 | 86.1 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 120 | 59.4 |

| 25–30 | 55 | 27.2 | |

| 31–40 | 13 | 6.4 | |

| Over 40 | 14 | 6.9 | |

| Nationality | Korean | 80 | 39.6 |

| Not Korean | 122 | 60.4 | |

| Frequency of Weverse visit |

Everyday | 67 | 33.2 |

| 3–5 times a week | 71 | 35.1 | |

| 1–2 times a week | 58 | 28.7 | |

| I do not visit even once a month | 6 | 3 | |

| Membership Subscription | ARMY Membership (22.00 USD) | 97 | 48 |

| ARMY Membership (160.00 USD) | 31 | 15.3 | |

| No subscription | 74 | 36.6 | |

| Social media used the most for interaction with ARMY | 68 | 33.66 | |

| YouTube | 18 | 8.91 | |

| Weverse | 77 | 38.12 | |

| 33 | 16.34 | ||

| V Live | 6 | 2.97 | |

| Social media used the most for interaction with BTS | 15 | 7.43 | |

| YouTube | 16 | 7.92 | |

| Weverse | 108 | 53.47 | |

| 37 | 18.32 | ||

| V Live | 26 | 12.87 | |

| Total | 202 | 100.0 |

| Construct | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIS | .694 | .932 | .912 |

| OI | .697 | .941 | .927 |

| PR | .576 | .871 | .820 |

| SOVC | .532 | .872 | .825 |

| LOY | .636 | .840 | .718 |

| MW | .556 | .918 | .902 |

| Hypothesis | Path | β | t | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | DIS → OI | .530*** | 10.544 | Supported |

| H2 | DIS → PR | -.065 | .893 | Rejected |

| H3 | OI → SOVC | .540*** | 8.003 | Supported |

| H4 | PR → SOVC | .391*** | 6.326 | Supported |

| H5 | SOVC → LOY | .520*** | 9.737 | Supported |

| H6 | SOVC → MW | .227*** | 4.271 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).