1. Introduction

Today, 3 billion city dwellers generate 1.3 billion tonnes of solid waste per year (ie 1.2 kg per person per day) and this volume of waste will rise to 2.2 billion tonnes in 2025 (ie 1.42 kg/capita/day) produced by 4.3 billion people worldwide. [

1]. With Africa's rapid urbanization and demographic growth, urban sanitation and waste management have become major concerns. The cities of African countries are increasingly under the influence of the household waste produced by their populations. The dwindling resources allocated to waste management and the lack of effective mechanisms for eliminating it are gradually damaging the image of these cities through the accumulation of huge quantities of waste, which until now has been a source of pollution. [

2]. The issue of waste and the problems it poses in Africa has been given fresh impetus by the rapid growth of the urban population and the disproportionate expansion of urban space. This is due to uncontrolled and uncontrolled urbanization in Africa. Collecting and disposing of solid waste poses serious problems, not only for municipal officials and central authorities, but also and above all for poor populations [

3].

A study in Côte d'Ivoire shows that waste management in African cities is often highly segregated along socio-spatial lines. The most disadvantaged sections of the population have less and less access to municipal waste collection services and are the most exposed to the nuisance of uncollected waste. However, Bonon's difficulties in managing its waste have led to a territorialization of waste in the town. Indeed, in Bonon the sanitation crisis with the problems of illegal dumping does not reveal the socio-economic differentiations and access to the waste collection service [

4]. A systemic analysis of waste management in Bonon reveals a derelict town where waste is far from being a social marker of consumption patterns. The composition of waste combined with the same social practices can be found in all the town's neighborhoods. Households dispose of their waste in septic tanks, illegal dumps or in the various streets. Beyond the issues related to waste typology and the popularization of bad social practices, the study reveals the link between the various pathologies (malaria, diarrhoea and typhoid fever) and the absence of communal collection through the spectrum of the city's growing insalubrity [

5].

In Guinea, household waste has become a crucial problem that is increasingly worrying both the local authorities and the people of Conakry, as the current waste management system is marked by major malfunctions. The collection rate, which was 70% in 1997, is now barely 20%, while the quantity of waste produced continues to rise (from 600 t in 1997 to more than 1,500 t in 2015) [

2]. The inoperative nature of household waste collection and disposal structures encourages the establishment of uncontrolled illegal dumps all over the city. Uncollected rubbish, uncontrolled sewage and degraded roads have become a nightmare for residents. As a result of this growing insalubrity, Conakry has taken on the image of a city held hostage by "mountains of rubbish". The latter have become the reflection of a dual socio-spatial configuration with the existence of a sort of "segregation" in the pre-collection and waste disposal service. While the main roads, administrative and commercial centers and wealthy neighborhoods benefit from a minimum collection service, working-class and poor neighborhoods, where high population densities lead to the production of large quantities of waste, are completely ignored. As a result, waste management is like two cities in one: one modern city with more or less waste collection, and another neglected city with unhealthy neighborhoods. Faced with these disparities, the authorities have developed and tested tools and are trying to find optimal management strategies. Unfortunately, the tools implemented have shown their limitations, as they have proved ineffective [

2].

Traveling around Togo's towns and cities, you can see the proliferation of unauthorized dumps along transport routes and the dumping of household waste in streams, giving the impression of an unhealthy and unsanitary environment. [

6]. The result is an environment assaulted by the mass of household and industrial waste produced, leading to all forms of pollution. [

7]. Such clichés tarnish the image of Togo, which its leaders present to international opinion as a "model country of stability and cleanliness".

It has been observed that there is a mismatch between the development of urban areas and the lack of urban structures, which encourages the proliferation of uncontrolled landfill sites throughout the country. So, what is the current waste management situation in underdeveloped countries? How is waste managed, particularly in Togo? What impact could this have on human health? The issues at stake in good waste management are the quality of the environment and public health. This approach makes it possible to identify and interpret the way in which urban waste collection and treatment operations are carried out and, ultimately, to develop a waste management policy for Togo's urban areas. The aim of this study is to identify the different solid waste management practices and approaches employed within the waste sector in Togo, and the extent to which waste recovery policies, regulations and applied technologies play a role in the context of solid waste management and the circular economy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study framework

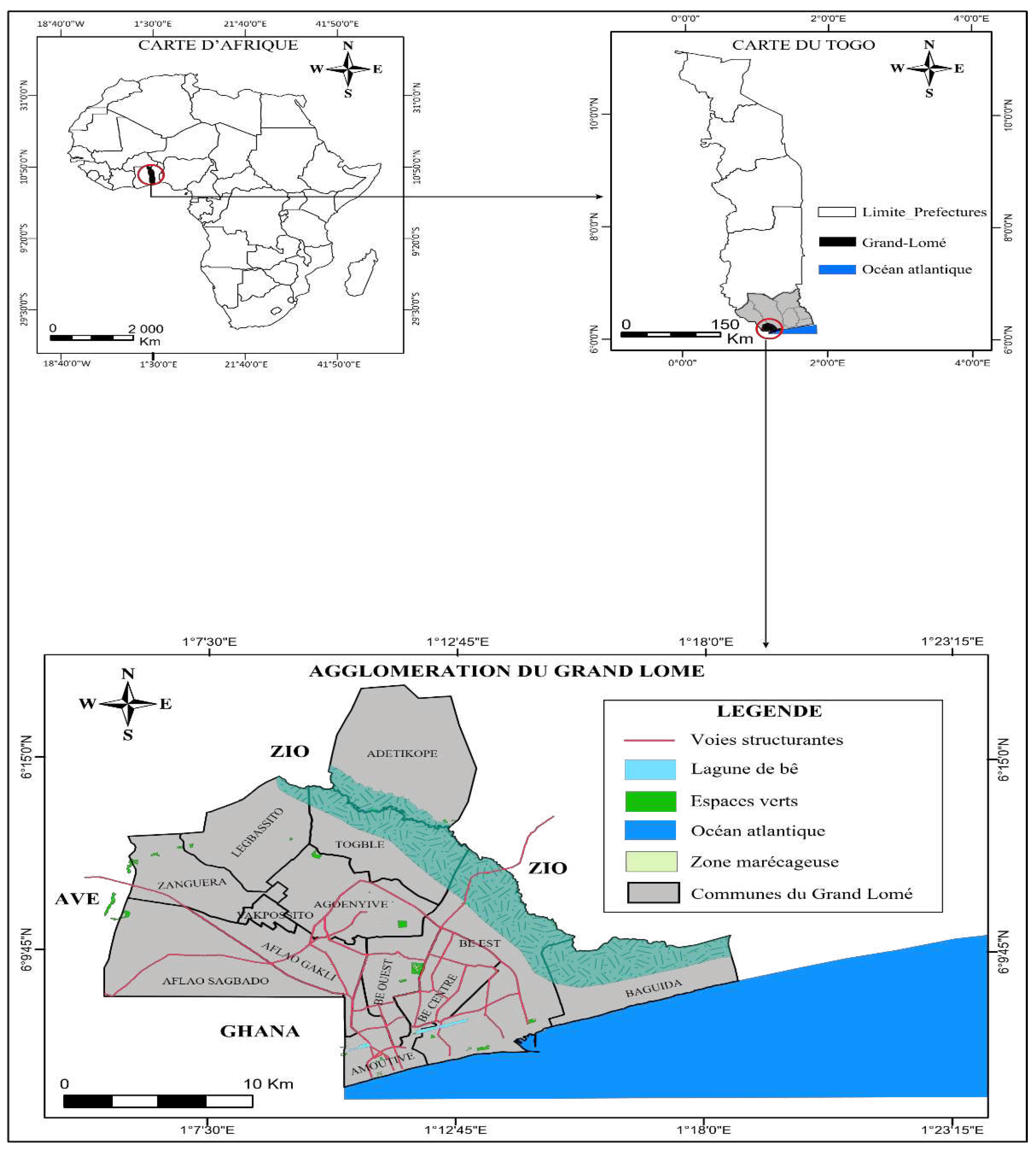

Togo is a sub-Saharan African country bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It is a small country covering an area of 56600 km². It is bordered to the north by Burkina Faso, to the south by the Atlantic Ocean, to the east by Benin and to the west by Ghana. Its capital, Lomé, lies on the Atlantic Ocean at 6°7' north latitude and 1°11' east longitude. The country is shaped like a rectangle, divided into 6 major regions from north to south: the Savanes Region, the Kara Region, the Central Region, the Plateaux Region, the Maritime Region and the Greater Lomé Region (

Figure 1).

2.2. Methods

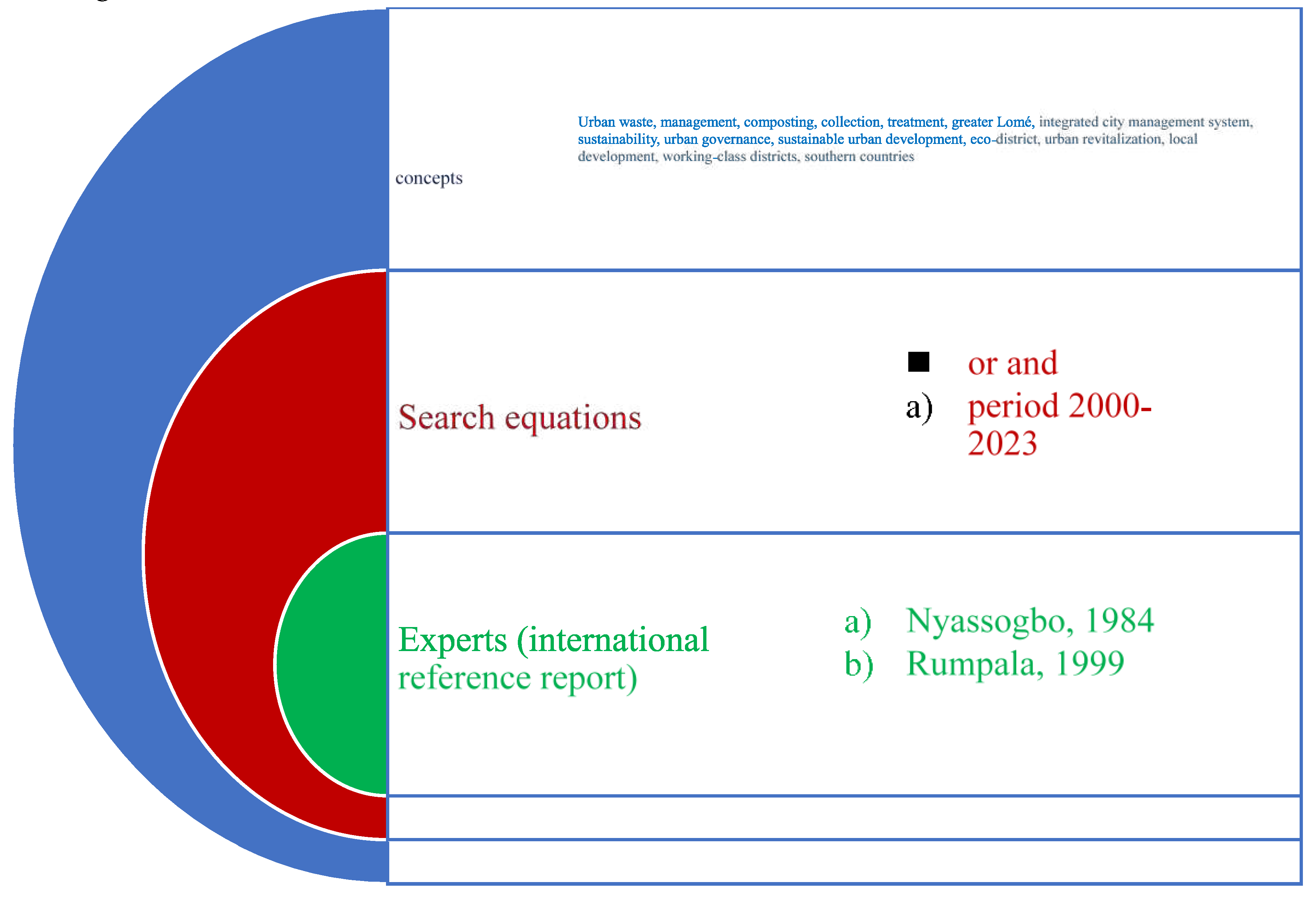

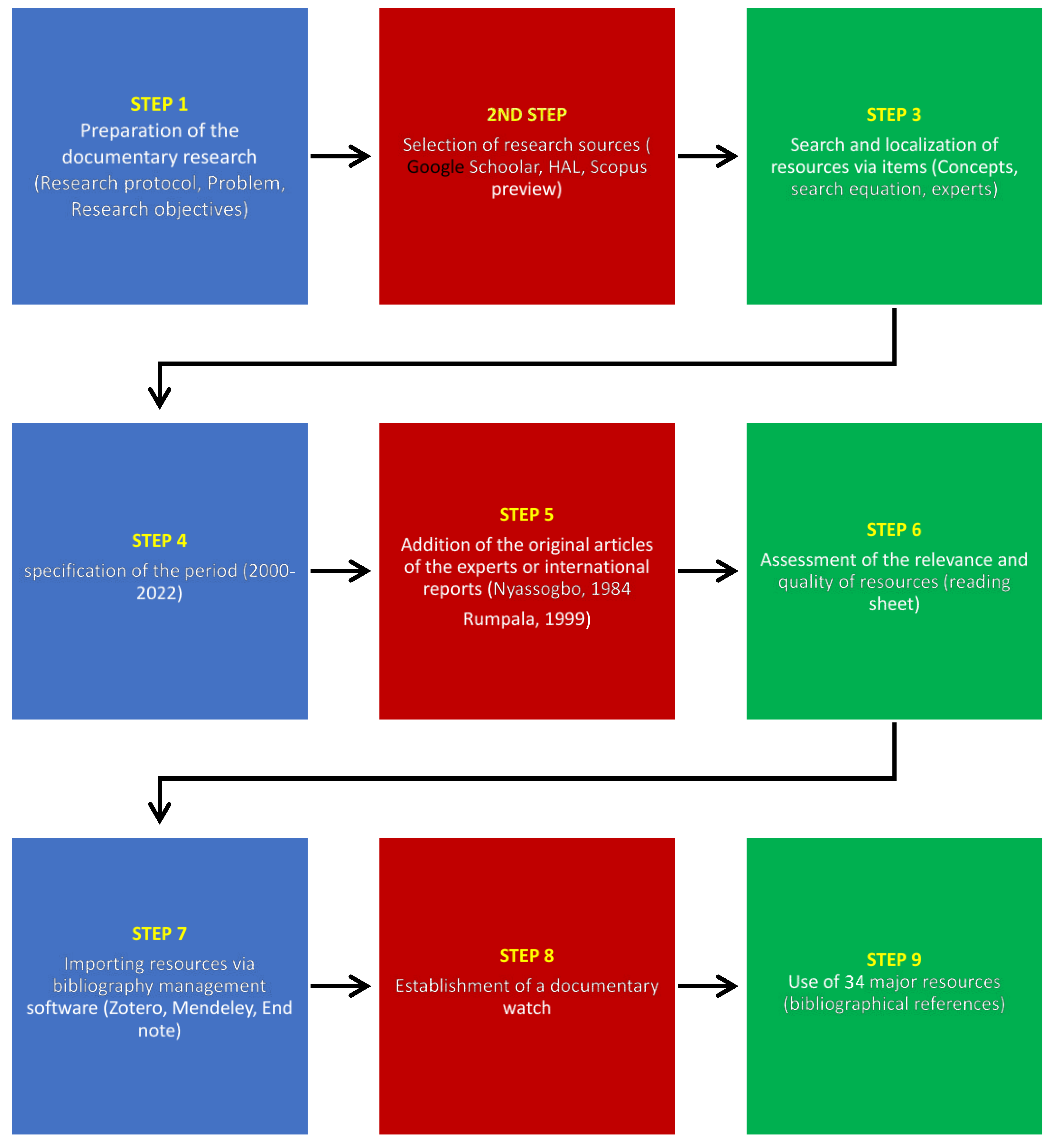

To achieve the objective of this work, which is to diagnose the current state and factual data on waste management in Greater Lomé, a major threat to public health, socio-economic development and the environment, we used documentary research and interviews with two types of waste management stakeholder, namely formal and informal waste managers in the five districts of Greater Lomé. This enabled us to make a general diagnosis. As regards the documentary search, a systematic literature review was carried out in the Scopus and google scholar databases using the key concepts of sustainable development (urban waste, management, composting, collection, treatment, Greater Lomé, integrated city management system, sustainability, urban governance, sustainable urban development, eco-districts, urban revitalisation, local development, working-class neighbourhoods, southern countries), with a search equation (and/or) for articles published from 2000 to 2022 with exceptions made for references to expert articles ( Nyassogbo, 1984 and Rumpala, 1999) (

Figure 2). The articles were evaluated in 9 stages in order to identify the most appropriate articles for inclusion (

Figure 3). A total of 34 articles, covering theoretical studies, field studies, conferences, reports of international studies and summits, and expert statements, were selected on the basis of content validity, relevance to the research question, strength of evidence, year of publication (2000 -2023) and relevance to sustainable resource management.

3. Results

3.1. Concept of municipal waste

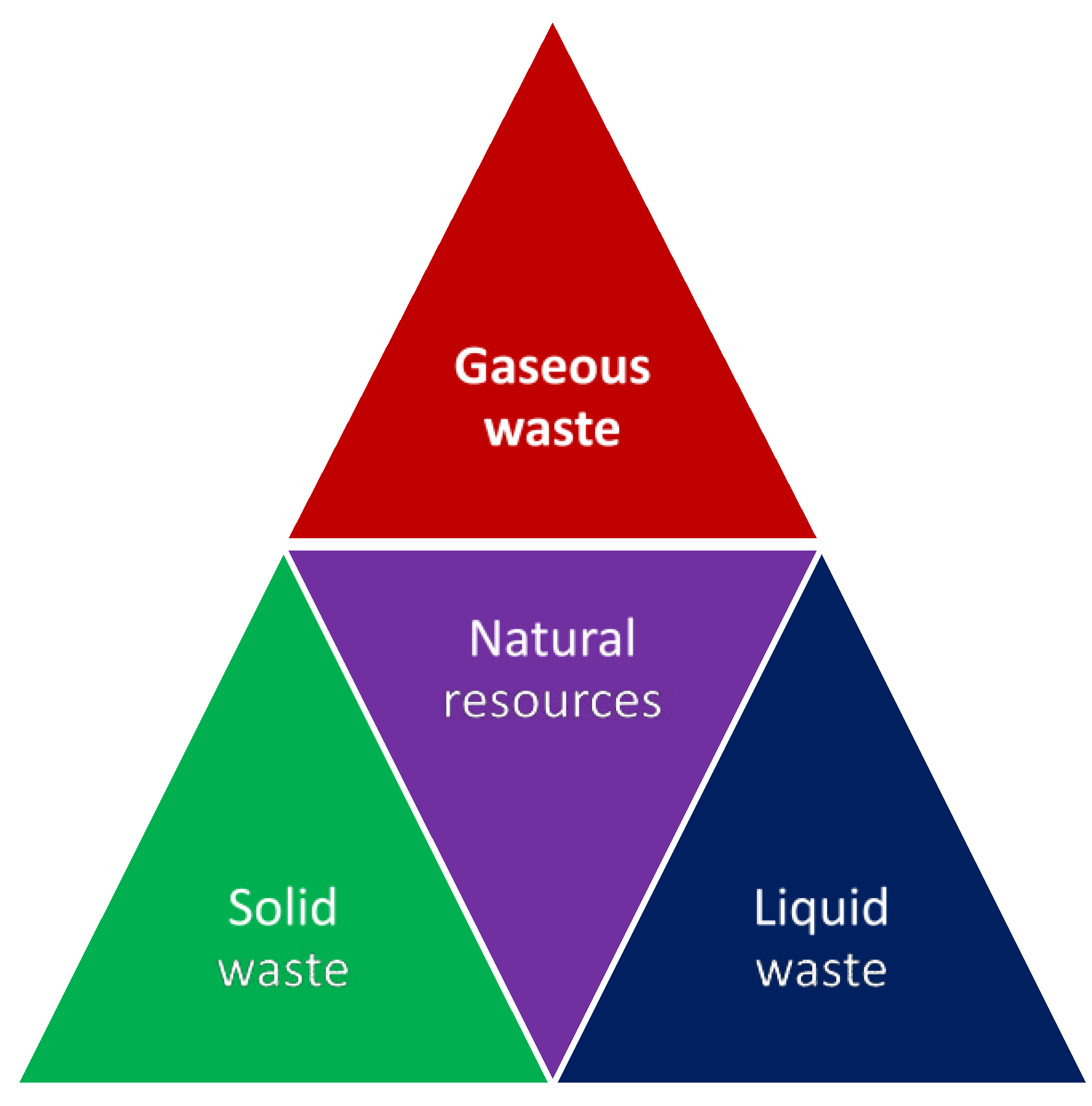

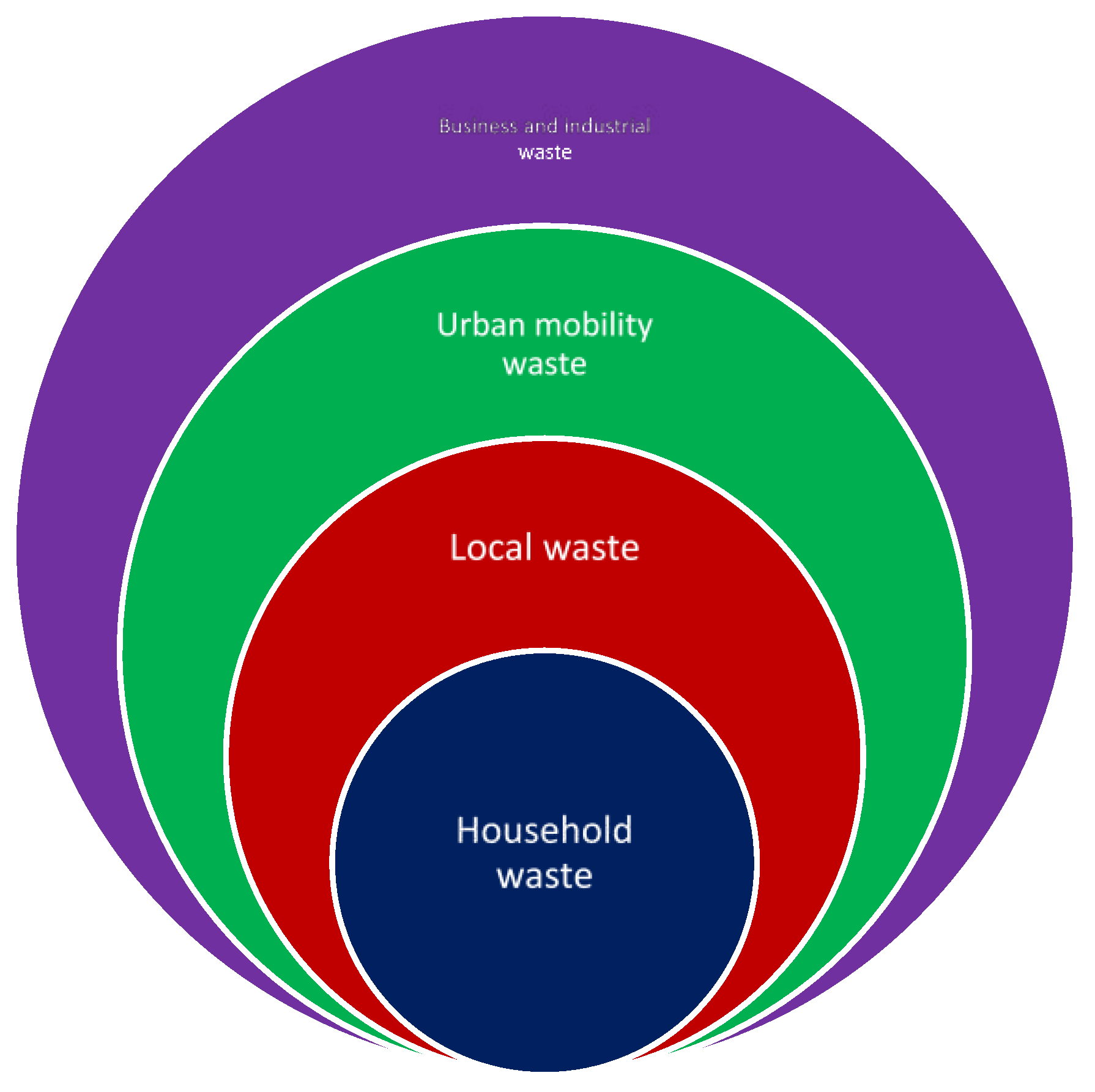

Urban solid waste is made up of all the residues produced by city dwellers and their activities. During our participant observation and surveys, the types of waste encountered left no doubt as to the nature of local consumption (

Figure 4). Urban waste includes household waste and industrial waste such as car wrecks and the carcasses of household appliances found in urban waste disposal sites. [

8]. Because of the scale of the pollution generated, and in line with business growth, industrial waste remains the category at the heart of the major problems (

Figure 5).

Household or domestic waste is waste produced within the household. Traditional societies had a system in place for reusing any waste they produced, whether it was clothes that were passed from generation to generation or potato and other peelings that were used as fertilizer for local crops (gardens). Nowadays there is no such thing as self-consumption or local recycling. As a result, the amount of packaging in household waste has increased. Excreta and liquid waste from septic tanks are also taken into account. For several years now, household waste management has had to contend with difficulties linked to the installation of treatment facilities, which systematically give rise to conflicts [

9].

Industrial waste differs from previous waste in that its composition and quantity vary. The manufacture of a new product automatically creates new types of waste that need to be dealt with. This category also includes waste from out-of-date food products, scrap or unsuitable products, paper and other packaging from administrative departments, as well as leftovers from canteens (boarding schools, restaurants) and public markets. All this waste is similar in composition to household waste. Finally, we should mention hospital and medical waste (from doctors' surgeries, dental surgeries, veterinary surgeries, clinics and hospitals), which is not classified as municipal waste, and liquid waste such as used oil. [

10]. Industrial processes inevitably produce a certain amount of liquid waste. It is then necessary to treat it, either to recover it or to dispose of it. Recovery involves regenerating the waste to extract raw materials, energy or complex reusable materials. Disposal, on the other hand, involves a process designed to transform the waste into a depolluted effluent that can be released into the environment, or into a product that can be stored over the long term. This article provides an overview of the main chemical and physico-chemical operations involved in the treatment of liquid industrial waste: oxidation-reduction, membrane processes, adsorption, solvent extraction, distillation, etc. For the time being, the production of non-ultimate waste, mainly from the industrial sector, seems inevitable. The treatment processes at specialized centers therefore have a number of objectives: (1) to enable total or partial recycling of this waste; (2) to facilitate its recovery in the form of materials or energy; (3) to enable its "eco-compatible" return to the environment after detoxification or stabilization-solidification; (4) finally, to break it down, more or less completely, into more "harmless" chemical species. [

11].

3.2. Waste management in developing countries

In developing countries, the rapid growth of the urban population and excessive urban sprawl have led to different lifestyles, resulting in higher waste production rates that those involved in waste management were unprepared to deal with. Large metropolises everywhere are collapsing under the considerable weight of the solid household waste produced by their inhabitants. They are characterized by an increasingly unhealthy and unsanitary environment. [

12]. The uncontrolled urbanization of Africa and the collection and disposal of solid waste are therefore posing serious problems, not only for municipal and central government officials, but also and above all for the people living in developing countries. It's not surprising to see mountains of household waste everywhere, especially in poor neighbourhoods: on the banks of streams and rivers, at the beach, on plots of land that have not yet been built on or are insufficiently built on, and even on pavements and roads. The problem of household waste accumulating in spontaneous and unauthorized dumps is a reflection of the low rate of waste collection by the services responsible for it. These rates are between 20% and 50% in the best of cases, depending on the human and financial resources and technical means available to the municipalities [

13].

3.3. Problem of waste management in Togo.

The Greater Lomé area is home to two million people, or a quarter of Togo's population (

Table 1). Each inhabitant produces an average of 0.6 kg of waste per day, and the capital emits 350,000 tonnes of household waste (organic, plastic, glass, paper, etc.) per year, barely 10% of which is recycled [

8].

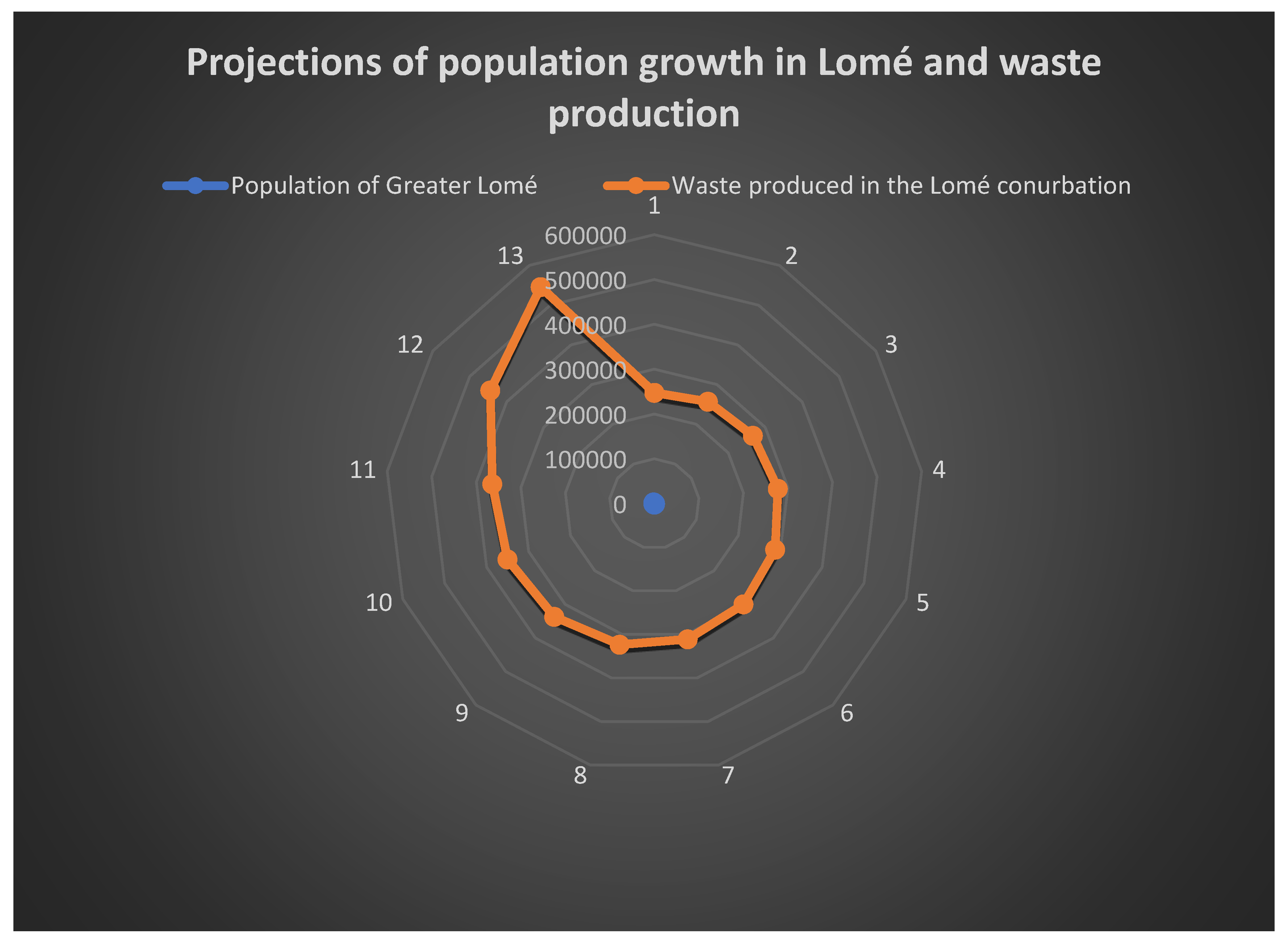

The problem with waste is that more than half of all plastic products manufactured are thrown away as waste. For example, of the 460 million tons of plastic produced in 2019, 353 million tons were thrown away. This disposal includes the acceptable (recycling, even if it is less than 9% overall), the bad (50% ends up in unmanaged landfills) and the ugly (the rest simply ends up poisoning the environment) (Hickey, 2023). Taking the statistics for 2019 in Togo, the Lomé conurbation produced 167.41605 tonnes of waste per thousand inhabitants, with projections of 545625.649 tonnes of waste per thousand inhabitants in 2030.

Despite some excellent initiatives, the collection, sorting and processing system is still inadequate. Many areas (streets, wastelands, lagoons, waterways) are clogged with waste, leading to numerous sewer overflows, and the burning of waste is a common practice that emits noxious fumes. Waste is produced exponentially in relation to the population (

Figure 6). So one of the major challenges facing local authorities is to set up a functional collection system. [

4]. It goes without saying that waste management is a major economic and environmental challenge for cities in developing countries. A World Bank report published on 6 June 2012 warned that household urban waste would increase by 70% worldwide by 2025 and that this would lead to a "sharp rise in the cost" of waste treatment in low-income countries [

15].

In Togo, on average, less than 20% of the population benefits from a household waste collection service. In general, urban dwellers benefit from full refuse collection, while rural areas are not collected at all. In towns, the systems for pre-collection or home storage and collection are very different. The same spatial segregation that applies to other urban infrastructures and services (water, energy, transport, etc.) also applies to waste collection. There are blatant disparities in the service between high-standard neighborhoods (housing estates) and those of mediocre standard (working-class neighborhoods). Very often, official waste collection is irregular and inadequate in the outlying districts. Communal bins are overflowing and the service fails to meet its commitments. The failure of the waste collection service to take charge of and treat the outlying neighbourhoods, on the one hand, and the lack of awareness of the health hazards of unauthorized dumps and dumpsites, on the other, contribute to the carelessness of residents when it comes to their collective urban space.

Modern business and residential districts generally have door-to-door waste collection; private individual bins, or communal bins in blocks of flats, are placed on the doorstep and emptied daily by the waste collection service. These neighborhoods benefit from maximum resources and therefore have few or no sanitation problems. The disparities we have just seen also exist between different towns in the country, whatever their size. This is the case for refuse collection in the residential areas of Lomé airport, the Cité Millénium and the Caisse.

3.4. Current waste management in Togo and Greater Lomé

Managing waste means trying to produce less of it, then recovering the materials it contains, and finally disposing of it in an environmentally safe way. In Togo, waste management is the responsibility of local authorities. However, they also sign 1-year contracts with private operators to collect waste. There are two possible scenarios for waste collection. In the first case, the Commune directly carries out this task on its own authority, employing its own municipal staff. This is what most of the country's Communes do. However, the inadequacy of municipal budgets, compared with the increase in collection costs, often limits this practice over time. The second scenario is where the Commune delegates this operation to a service provider such as ANASAP (National Agency for Sanitation and Public Health).

Landfill sites still appear to be the main destination for community waste (

Figure 7), accounting for 9-79% of the total amount of waste collected; some (8-37%) is burned in neighborhoods or at the dumping site; the remainder (manure and other waste) makes up the remaining 3-9%, mainly in the Gulf prefecture. The example of this prefecture is indicative of the situation in all Togolese towns. On the other hand, the town council does not have the resources to collect all the household waste it generates. The lack of access roads and the poor habits of residents in underprivileged neighborhoods complicate the management of urban rubbish. In the minds of some residents (those in the outlying districts), it is up to the agents of the service providers responsible for waste collection to pick up the rubbish, wherever it is located. An organization based on the seven (7) existing arrondissements has enabled tasks to be shared out. A solution was thus found by privatizing the urban waste collection sector, with the State, through the Municipalities and the Ministry of the Environment, sharing responsibility for urban waste management.

Figure 7.

Adétikopé center public dump (Commune Agoè-Nyivé 5), Togo.

Figure 7.

Adétikopé center public dump (Commune Agoè-Nyivé 5), Togo.

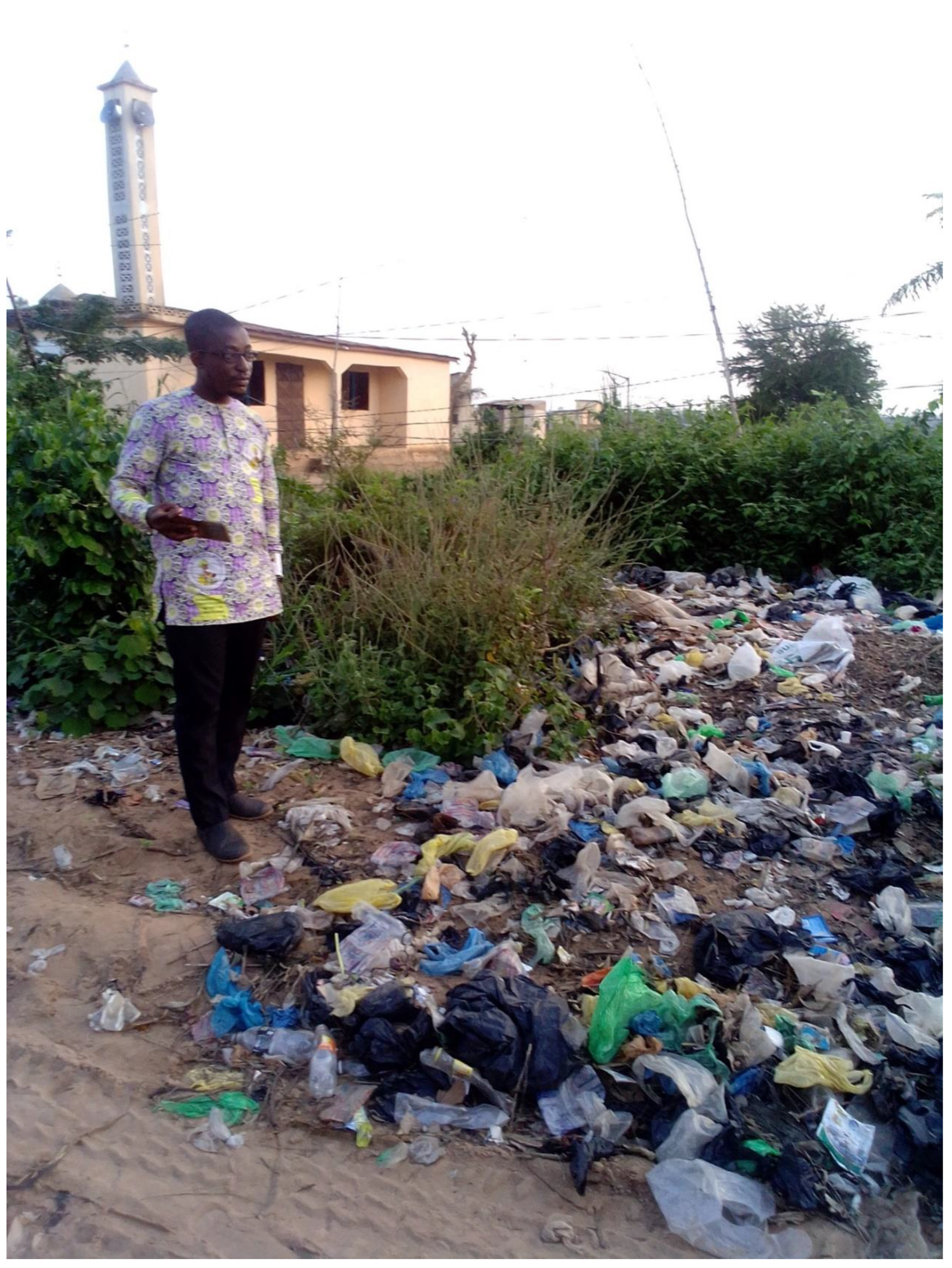

Figure 8.

Garbage dump next to a House in Kpokpomé Agouté (Commune Agoè-Nyvé 6), Togo.

Figure 8.

Garbage dump next to a House in Kpokpomé Agouté (Commune Agoè-Nyvé 6), Togo.

Figure 9.

Waste production and demographic projections for the Lomé conurbation (2010-2030).

Figure 9.

Waste production and demographic projections for the Lomé conurbation (2010-2030).

Figure 10.

DJOVE public dump (Commune Agoè-nyvé 6, Togo).

Figure 10.

DJOVE public dump (Commune Agoè-nyvé 6, Togo).

Figure 11.

Garbage dump next to a House in Kpokpomé Agouté (Commune Agoè-Nyvé 6), Togo.

Figure 11.

Garbage dump next to a House in Kpokpomé Agouté (Commune Agoè-Nyvé 6), Togo.

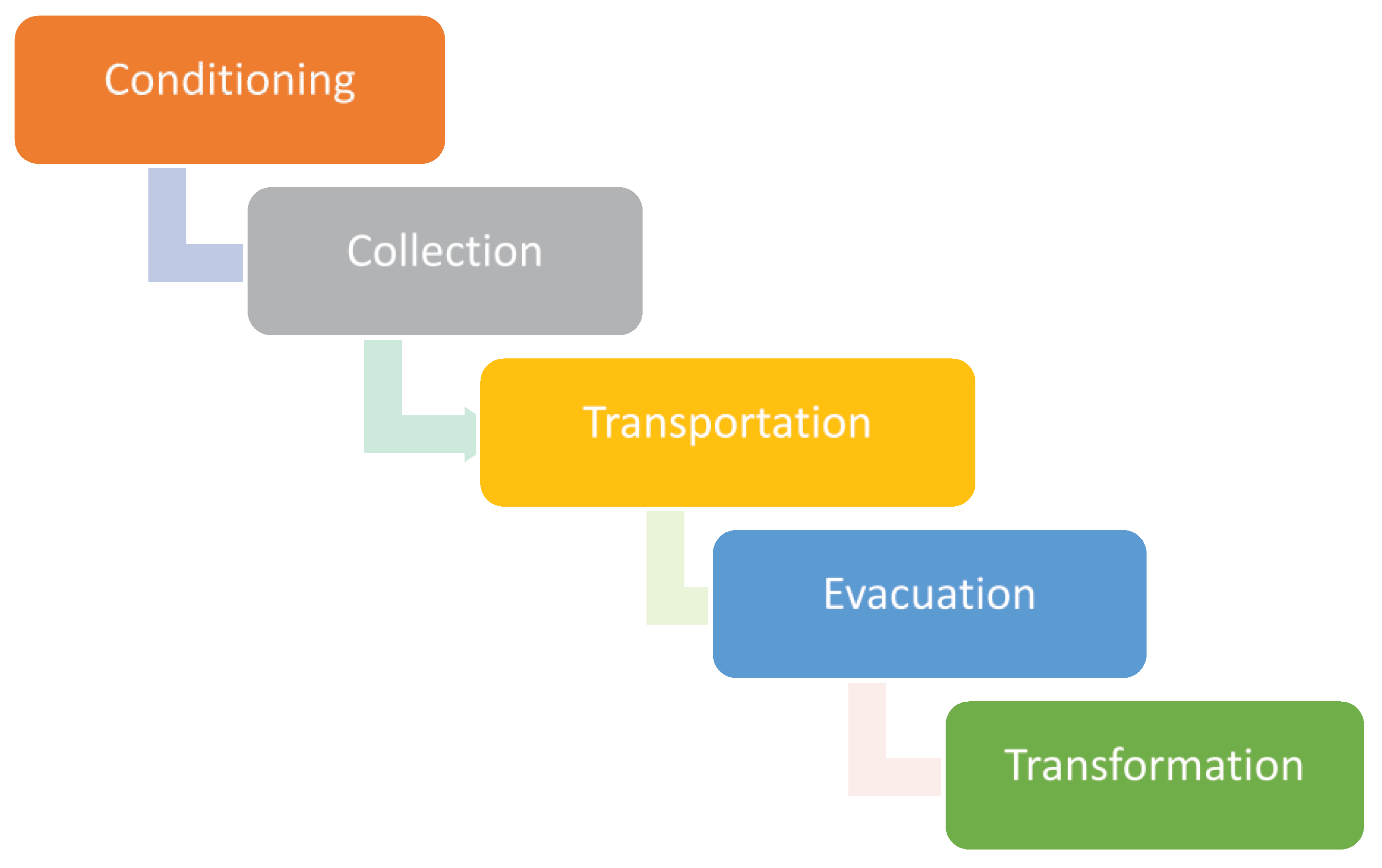

Figure 12.

Summary diagram of the waste management circuit Source (Gbekley, 2023).

Figure 12.

Summary diagram of the waste management circuit Source (Gbekley, 2023).

In Greater Lomé, as in other cities in Togo, waste collection was, until recently, carried out at three levels: the first level was for pre-collection, in the markets, by associations and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); the second level was for collection, in the markets and districts, by private companies selected after a call for tenders; the third level was for intervention by the Lomé City Council in the markets and their surroundings. The final landfill was at Agoe. Since 1996, the municipal authorities have realized that this landfill was saturated. All the players involved have always been unanimous about the need to find another site, and to carry out a study for the establishment of a new landfill that meets the appropriate standards laid down in this area. A major step forward in waste management is the creation of a Technical Landfill Center (CET). Other initiatives include the promotion of waste recovery and recycling.

3.5. Composting, a waste management model still in use in Greater Lomé

Composting was practiced in ancient times. For thousands of years, the Chinese have collected and composted all the matter from their gardens, fields and homes, as well as faecal matter. In the Near East, at the gates of Jerusalem, there were appropriate places to collect urban waste. Some waste was burnt and others composted. Composting is an aerobic microbiological process of decomposition and synthesis of organic matter; its main enemy, and very serious drawback, being plastic. These transformations are due to the bacteria, actinomycetes and fungi contained in the waste. [

16].

For a number of years now, thanks to the winds of technological transition, new players involved in private-public partnerships have been working alongside public authorities to help manage urban waste by proposing innovative solutions with a view to the circular economy.

3.6. Some waste recycling projects in Togo.

Clean Natural Ecosystem (ENPRO): In Togo, a project to focus on waste recovery has been running since 2011. This is the Africompost Lomé project run by ENPRO and GRET in partnership with the Commune of Lomé and now with the Autonomous District of Lomé. [

15]. The aim of Africompost is to improve waste management in the city of Lomé by developing recycling through composting. The players involved in this project are in daily workshops to share their experience of waste management, the environment, urban development and agriculture in Lomé. [

15].

Project to improve waste management through composting and concerted action in the neighborhoods of Lomé (Togo), led by Gevalor and subsidized to the tune of €300,000 by Syctom: Lomé, the capital of Togo, is home to 25% of the country's population. Faced with difficulties in managing its household waste, the city has been modernizing its solid urban waste management scheme since 2007, with financial support from the Agence Française de Développement. The first phase of the project (2007-2012) focused mainly on reorganizing the pre-collection and waste collection channels, and on developing transit sites, but the collection rate remains low and illegal rubbish dumping still persists. The second phase (2013-2019) focuses more on the solid waste treatment phase and on the construction of a new landfill site at Aképé to replace the current landfill at Agoé, which is saturated. The project led by Gevalor aims to improve the waste collection service in three urban districts of the city of Lomé and to support the activities of the ENPRO association, which has developed the composting platform as part of the Africompost programme. Syctom provided support during an initial phase (October 2017-December 2018) to the tune of 98,250,000 FCFA (€150,000). This phase led to a number of advances, such as an awareness-raising plan, the definition of a labeling framework, a diagnosis of pre-collection, work on reducing sand in waste, and improvements in compost quality. The second phase of the project, subsidized to the tune of 98,250,000 FCFA 150,000 in 2018, should make it possible to: (i) improve the waste collection service and household behaviour: raise awareness among households about subscribing to pre-collection, support pre- collection structures to gain access to the label, test operation to reduce sand in waste, consultation between the various stakeholders and the municipality on the organization and cost of the waste management service; (ii) make waste recovery sustainable by consolidating all the activities of ENPRO (the association that provides pre-collection and manages the composting platform) in an entrepreneurial approach: training of composting staff, training and support for ENPRO in entrepreneurial management tools, actions to popularizes compost among farmers, etc. [

17].

Ecobox" project to recycle solid waste in Togo. Aného, in the south-east of the country, will serve as a pilot town for the launch of the "Ecobox" solid waste recycling project in Togo by the telecommunications group Togocom and Africa Global Recycling (AGR) .The initiative is part of a three-year program : In Togo, the private sector is supporting the government's solid waste management policy.Just recently, Togocom and Africa Global Recycling (AGR), a company specializing in waste recycling, launched the "Ecobox" project. The initiative aims to reduce the proliferation of waste in Togolese towns and cities. The project is the first phase of a three-year program. The two partners have launched the pilot phase of "Ecobox" in Aného. In this coastal town in south-east Togo, the project involves the installation of three Ecoboxes for the collection of solid waste, in the commune of Lacs 1. The facilities will be used to recover and buy back recyclable solid waste from local people and players in the informal sector. Togocom and AGR will recruit three waste eco-collectors to facilitate collection in Aného. The "Ecobox" project will then be rolled out to other towns in Togo. AGR will recycle the waste collected. The recycled products will be sold to companies looking for low-cost raw materials. " We will be setting up new types of sales outlets for Tmoney products and services", says telecommunications operator Togocom.

Mitigating solid waste pollution: In order to achieve effective results, Togocom plans to integrate digitization into the solid waste collection and recovery process in Togo. This should help to reduce soil and water pollution. According to the National Agency for Sanitation and Public Safety (ANASAP), individual waste production in Togo is within the norm for developing countries, at 0.4 to 2 kg per inhabitant per day.

Biogas production: In Togo, some of the waste produced will soon be converted into biogas, at Kloto in the Plateaux region. Biothermica Technologies is implementing the project at a cost of 250 million CFA francs (over €381,000). The Canadian company believes that converting waste into biogas should provide a lasting solution to the problem of waste pollution in Kloto and reduce emissions of 260,000 tonnes of CO 2 by 2030 in Togo [

18].

4. Discussion

This study used a methodology based on fieldwork coupled with documentary research. This methodology is beneficial in that the literature on waste management is fairly rich and complements the field data obtained. This study deals with a crucial environmental issue in Africa in general and in Togo in particular. Among the five scourges threatening the environment in sub-Saharan Africa, waste pollution features prominently, alongside desertification, deforestation and toxic waste pollution. The problem of plastic waste is a story that began as an environmental crisis, and quickly became an economic and health crisis. And it is a story that cuts across the three global crises we are facing today: biodiversity, climate and pollution [

19].

Thinking about effective solid waste management in Africa is a squaring of the circle in which most sub-Saharan cities are trapped. For a number of years now, West Africa has been looking at ways of effectively managing urban waste. West African cities have been undergoing rapid and continuous demographic and spatial expansion for several decades, with the development of new lifestyles and catering facilities [

20]. Africa seems to be lagging behind when it comes to environmental issues and urban waste management. Solid waste management has become one of the main environmental problems facing municipal authorities. It has been exacerbated in recent years by the sharp increase in the volume of waste generated and by qualitative changes in its composition [

21] As a result, African cities such as Lomé and its inland municipalities are crumbling under the weight of rubbish, and diseases (dysentery, diarrhoea, malaria, etc.) linked to insalubrity are legion.

In terms of urban waste management, increasingly stringent regulations have been put in place since the 1970s to resolve environmental issues and make better use of waste, with a view to achieving a circular economy. Two approaches are generally proposed to solve the problem of waste management. The first is to ensure that waste is managed through treatment processes whose recovery targets are constrained by product type. The second is based on the prevention of waste generation through product eco-design, which (i) extends the product's lifespan and (ii) ensures that it is better recycled at the end of its life. This article focuses on strengthening the link between these two axes by proposing indicators that complement recoverability rates, enabling designers to better understand the effectiveness of recovery in the various end-of-life treatment routes [

22].

In today's consumer society, the mass production and consumption of goods leads to the generation of large quantities of municipal waste. Initially, little attention was paid to the environmental burden of mass consumerism, and municipal waste was destined for disposal in landfill sites. Since the 1960s, society's growing concern about health and environmental risks has prompted the implementation of advanced waste management systems in developed countries [

23]. Although local players believed in this and did their utmost to promote management models, the public authorities, dominated by the central government, were not sufficiently equal to the public actions decided on in terms of environmental management. Indeed, fearing the worsening situation today, urban areas have seen the introduction of management systems since the end of the 1980s based on sorting and selective collections as part of the reorientation of household waste management. The development of these practices presupposes a commitment on the part of the population, which affects not only the relationship they have with their waste, but also a whole range of relationships with the institutional spheres, both administrative and economic. We therefore need to look back at the involvement of users in order to understand how such a solution could become apparently consensual [

24].

With regard to Lomé in particular, studies have been carried out with a view to managing urban waste and effluents. There is a considerable body of literature on the subject, including technical reports that are still current or need updating, such as those produced by the GIZ, platforms such as ENPRO and research laboratories such as the GTVZ. Today, urban waste management in Togo is possible and is becoming a condition for the sustainable development of our territories in that it promotes added value, that of the circularization of the Economy [

25]. Today it is increasingly clear that the current linear economy model (take-make-throw) has substantial limits and does not seem to be able to achieve the sustainable development objectives that now dominate the agenda of decision-makers at global level. Increasing attention is therefore being paid to developing policies that enable a transition to a circular economy model [

26]. People living near the landfill sites at Agoe in the commune of Agoé and Aképé in the commune of Avé in Togo have ended up developing a very lucrative business there, proving to everyone that recycling and recovery are feasible and a source of employment: it is possible to make a living from the transformation of the landfill site [

27]. The study into setting up a technical landfill center for waste therefore became an absolute priority. In the interests of fairness, despite the financial and technical obstacles facing the waste management sector, ongoing attempts are being made to divert waste from landfill sites to certain advanced recycling facilities. Indeed, most providers are approaching sustainable waste management solutions and most decision-makers are identifying their problems and past mistakes to implement a solid waste management system. The performance of the many players is worthy of encouragement and improvement, with the support of the Government and the goodwill of all. Finally, the financial stakes, seen solely as a source of gain, are a hindrance to the opportunities offered by the growing waste market and to rational waste management. This study has enabled us to diagnose waste management in Togo, and particularly in its capital, Lomé, and to identify the obstacles and challenges to setting up a management system that promotes a circular economy. Awareness is also being raised of the need to move towards implementing waste management in the context of a circular economy [

21]. The empowerment of Communes in application of the law on decentralization, the organization and promotion of local initiatives and the private sector should, in principle, make it possible to overcome the difficulty of managing Togolese urban waste [

28,

29,

30,

31]. In view of the new governance data in line with sustainable development, it is urgent that the public authorities focus actions on the real needs (supply of drinking water, management of solid urban waste, wastewater and excreta) of the population and territories. in demographic change [

32]. As some authors have proposed, the comparative analysis of the specific management possibilities between the different municipalities could make it possible to assess the courses of action to improve sustainable social practices [

33]. Making a country green is crucial to ensure the survival of humanity, given the current climate crisis. A nation's entire productive matrix and related production processes must therefore be sustainable to achieve this goal. This should be done taking into account relevant factors and issues, such as sustainability [

34].

5. Conclusion

Solid waste management has become one of the main environmental problems facing municipal authorities in the Greater Lomé Autonomous District of Togo. It has been exacerbated in recent years by the sharp increase in the volume of waste generated and by qualitative changes in its composition. The provision of adequate waste management services is essential because of the potential impact on public health and the environment. The lack of planning, the absence of appropriate disposal, the inadequacy of collection services, the use of inappropriate technologies, inadequate funding and the limited availability of skilled and qualified manpower, as well as the sudden massive increase in population, are considered to be the main problems facing solid waste management in the region.

The aim of this study was to identify the different solid waste management practices and approaches employed in Togo, and the extent to which the policies, regulations and technologies applied play a role in the context of solid waste management and the circular economy.

The study revealed that most of the waste management problems in the countries analyzed appear to be due to political factors and the decentralized nature of waste management, with management and responsibilities at several levels. Material and energy recovery in the context of municipal solid waste management does not differ significantly between communes in Togo. As a result, a fresh look is needed and it is necessary to move from a linear economy of "waste management" to a circular economy model of "resource efficiency". The latter can be achieved by adopting a common vision of how the solid waste management system can be transformed into a circular economy. Since they are the main drivers of any transition to a circular economy system, the existing policies, strategies and practices that govern waste management performance in the region need to be reviewed. Currently, there is a consensus among local authorities that the success of any sustainable waste management solution requires the participation and cooperation of all parties involved in the sector, such as international companies, local private companies and municipalities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GBEH, GASH; Methodology, GBEH, KLBM, PA ; Software, GBEH; Validation, PA; Formal analysis, GBEH, AN, FCK, ; Survey, GBEH, AAGVA , AA, LBMK ; Resources, EIE , AMA , YA; Data curation, GBEH, LBMK ; Original drafting, GBEH; Drafting-reviewing and editing, GBEH, PA; Visualization, MV, KA ; Supervision, PA. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Regional Center of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA_DOUNEDON), the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the World Bank.

Statement by the Institutional Review Board

Not applicable.

Declaration of informed consent

Not applicable.

Declaration of data availability

data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Regional Center of Excellence on Sustainable Cities of Africa (CERViDA_DOUNEDON), the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the World Bank for providing the necessary funding that facilitated our research work leading to these results. We would also like to express our gratitude to Cyprien AHOLOU, and Kossiwa ZINSOU-KLASSOU, for their support and enlightened leadership in promoting this Center of Excellence.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Durand, M. La gestion des déchets dans une ville en développement: comment tirer profit des difficultés actuelles à Lima? Flux 2012, 87, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangoura, M.R. Gestion des déchets solides ménagers et ségrégation socio-spatiale dans la ville de Conakry. phdthesis, Université Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2017.

- Nyassogbo, K. L’urbanisation et Son Évolution Au Togo. Cah. O.-m. 1984, 37, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gbinlo, R. Organization and financing of the management of household waste in the cities of Sub Saharan Africa : a case study of Cotonou, Benin Sumary : recent attempts explaining the links between. phdthesis, Université d’Orléans, 2010.

- Florent, G.; Yao-Kouassi, Q. Système de Gestion Des Déchets et Vulnérabilité Des Populations de Bonon (Côte d’Ivoire). Rev. Ivoirienne Géographie Savanes RIGES, 2022; 120–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gbekley, E.H.; Kouawo, A.C.A.; Awokou, K. L’éducation Relative à l’environnement (ERE) Au Togo : Evaluation Du Paradigme de Formation 2021.

- Bromblet, H. Diagnostic de la gestion des déchets à Lomé. 2015, 45.

- Kondoh, E.; Bodjona, M.B.; Aziable, E.; Tchegueni, S.; Kili, K.A.; Tchangbedji, G. Etat Des Lieux de La Gestion Des Déchets Dans Le Grand Lomé. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 2200–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocher, L. Gouverner les déchets. Gestion territoriale des déchets ménagers et participation publique. phdthesis, Université François Rabelais - Tours, 2006.

- Aymonier, C. Traitement hydrothermal de déchets industriels spéciaux. Données pour le dimensionnement d’installations industrielles et concepts innovants de réacteurs sonochimique et électrochimique. phdthesis, Université Sciences et Technologies - Bordeaux I, 2000.

- Ouzir, M. Gestion Ecologique Des Déchets Solides Industriels, Misla, Université Mohamed Boudiaf, 2008.

- Nyassogbo, G.K. Repenser le développement africain : au-delà de l’impasse, les alternatives 19. 2005, 19.

- Nyassogbo, G.K. La Zone Lagunaire de Lome : Problèmes de Dégradation de l’environnement et Assainissement. Ann. L’Université Omar Bongo 2005, 391–409. [Google Scholar]

- DGSCN; PNUD; UNICEF RGPH. Résultats Définitifs Du Recensement Général de La Population Du 06 Au 21 Novembre 2010; Présidence de la République togolaise, Ed. 2010.

- Vert Togo Togo/ Valorisation des déchets: Les acteurs du projet Africompost à l’heure du bilan. VERT TOGO Au Coeur Inf. 2020.

- Mombo, J.-B.; Edou, M. La Gestion Des Déchets Solides Urbains Au Gabon. Geo-Eco-Trop 2005, 29, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Syctom Gestion Des Déchets - Togo - Lomé - Syctom. Available online: https://www.syctom-paris.fr/engagements/action-internationale/solidarite-internationale/les-projets-soutenus-dans-le-monde/togo-lome.html/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Magoum, I. TOGO : Togocom s’associe à Africa Global Recycling pour le recyclage des déchets. Available online: https://www.afrik21.africa/togo-togocom-sassocie-a-africa-global-recycling-pour-le-recyclage-des-dechets/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Hickey, V. Nous Ne Pouvons Pas Avoir Un Monde sans Pauvreté Dans Un Monde Avec La Pollution Plastique. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/we-cant-have-world-without-poverty-world-plastic-pollution (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Adjalo, D.K.; Houedakor, K.Z.; Zinsou-Klassou, K. Usage Des Emballages Plastiques Dans La Restauration de Rue et Assainissement Des Villes Ouest-Africaines : Exemple de Lomé Au Togo. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2020, 14, 1646–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemidat, S.; Achouri, O.; El Fels, L.; Elagroudy, S.; Hafidi, M.; Chaouki, B.; Ahmed, M.; Hodgkinson, I.; Guo, J. Solid Waste Management in the Context of a Circular Economy in the MENA Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Leal, J.; Pompidou, S.; Charbuillet, C.; Perry, N. Efficacité Potentielle de Valorisation: Proposition d’indicateurs à l’usage Du Concepteur Pour Mieux Prendre En Compte l’efficacité Des Voies de Traitement Du Produit En Fin de Vie. 2019.

- Joseph, A.M.; Snellings, R.; Van den Heede, P.; Matthys, S.; De Belie, N. The Use of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Ash in Various Building Materials: A Belgian Point of View. Materials 2018, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumpala, Y. Le Réajustement Du Rôle Des Populations Dans La Gestion Des Déchets Ménagers : Du Développement Des Politiques de Collecte Sélective à l’hétérorégulation de La Sphère Domestique. Rev. Fr. Sci. Polit. 1999, 49, 601–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, J.-C.; Aurez, V. Économie Circulaire, Écologie et Reconstruction Industrielle 2013.

- Jacometti, V. Circular Economy and Waste in the Fashion Industry. Laws 2019, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENPRO-Togo Valorisation Des Déchets Available online:. Available online: https://www.enpro-togo.org (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Fernandez, D.B.; Petit, I.; Lancini, A. L’économie circulaire : quelles mesures de la performance économique, environnementale et sociale ? Rev. Fr. Gest. Ind. 2014, 33, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, A.; Bourdin, S.; Torre, A. L’économie circulaire, quels enjeux de développement pour les territoires ? Dév. Durable Territ. Économie Géographie Polit. Droit Sociol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les enjeux d’écoconception associés à l’économie circulaire; Réseau EcoSD, Ed. ; Développement durable; Mines ParisTech-PSL: Paris, 2019; ISBN 978-2-35671-580-7. [Google Scholar]

- Suez AFRIQUE : L’économie Circulaire Au Cœur de La Préservation Des Écosystèmes | Afrik 21 Available online:. Available online: https://www.afrik21.africa/afrique-leconomie-circulaire-au-coeur-de-la-preservation-des-ecosystemes/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Gbekley, E.H.; Houedakor, K.Z.; Komi, K.; Poli, S.; Adjalo, K.; Nyakpo, A.; Ayivigan, A.M.; Ali, A.A.G.V.; Zinsou-Klassou, K.; Adjoussi, P. Urban Governance and Sanitation in the Peri-Urban Commune of Agoè-Nyvé 6 in Togo: Diagnosis of the Sanitation System in Adétikopé 2023.

- Ndam, S.; Touikoue, A.F.; Chenal, J.; Baraka Munyaka, J.-C.; Kemajou, A.; Kouomoun, A. Urban Governance of Household Waste and Sustainable Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Study from Yaoundé (Cameroon). In Proceedings of the Waste; MDPI, 2023; Vol. 1; pp. 612–630. [Google Scholar]

- Beguedou, E.; Narra, S.; Agboka, K.; Kongnine, D.M.; Afrakoma Armoo, E. Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management. In Proceedings of the Waste; MDPI, 2023; Vol. 1; pp. 654–671. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).